High Value High Risk 2016–17: Delivering HVHR Projects

Overview

Victoria's total estimated investment in new and existing capital projects in the 2016–17 Budget Papers is $57.7 billion. In June 2016 the total estimated investment of high value high risk (HVHR) projects was around $40 billion.

This is the third in a series of audits on the HVHR process. In June 2014, we tabled our first audit report in this series, Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects. In August 2015, we tabled our second report, Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals.

In this audit, we examined whether the HVHR process has been effectively updated and applied to provide sufficient and reliable assurance about the deliverability of HVHR projects. To do this, we examined whether agencies had implemented recommendations from our 2014 and 2015 HVHR audits. Using a sample of five HVHR projects in the delivery stage, we also tested whether the Department of Treasury & Finance's oversight of HVHR projects had improved the implementation of HVHR projects by better identifying and addressing risks that threaten project deliverability.

The report includes three recommendations for the Department of Treasury & Finance.

High Value High Risk 2016–17: Delivering HVHR Projects: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2016

PP No 216, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit High Value High Risk 2016–17: Delivering HVHR Projects.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

26 October 2016

Audit overview

Victoria’s total estimated investment in new and existing capital projects in the 2016–17 Budget Papers is $57.7 billion. In June 2016 the total estimated investment (TEI) of high value high risk (HVHR) projects was around $40 billion.

A project is classified as HVHR if:

- the TEI is greater than $100 million, funded through the Budget process, regardless of funding source; and/or

- the investment is identified as 'high risk' to government using an appropriate risk assessment process; or

- government identifies the investment as warranting extra rigour.

The government's 'high value high risk project assurance framework and budget process' (the HVHR process) was introduced in 2010 and is part of the Investment Lifecycle Framework (ILF). The HVHR process aims to achieve greater rigour in investment development and oversight, increasing the likelihood of project delivery on time and realised benefits for Victorians.

This is the third in a series of audits on the HVHR process. In June 2014, we tabled our first audit report in this series, Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects. In August 2015, we tabled our second report, Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals.

In this audit, we examined whether the HVHR process has been effectively updated and applied to provide sufficient and reliable assurance about the deliverability of HVHR projects. To do this, we examined whether agencies had implemented recommendations from our 2014 and 2015 HVHR audits. Using a sample of five HVHR projects in the delivery stage, we also tested whether the Department of Treasury & Finance's (DTF) oversight of HVHR projects had improved the implementation and delivery of HVHR projects by better identifying and addressing risks that threaten project deliverability.

Conclusion

DTF and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) have commenced appropriate actions to address all of the recommendations from our 2014 and 2015 HVHR audit reports. However, we have been unable to fully assess the application of the revised market-led proposal guidelines, because no proposal has been initiated and progressed to negotiation and final contract offer stage of the process since the revised guidelines were introduced in November 2015.

DTF has sufficient information to identify and monitor the known risks to HVHR project deliverability and advises the Treasurer in a timely manner about significant risks and possible remedial actions and interventions. However, it relies on timely and accurate reporting by agencies, particularly when DTF is not represented on project-level steering committees.

Without representation on a project-level committee, DTF does not have complete assurance that:

- all risks to project delivery are being identified in a timely manner

- project governance arrangements are effective

- progress reports on project delivery are accurate and reliable.

DTF and departments did not sufficiently consider and monitor interdependent investment risks, particularly for HVHR projects in the transport sector, where some projects rely on the delivery of other projects. Because monitoring and reporting activities are largely focused on individual projects, these interdependent project risks are not being effectively managed or monitored.

For fast-tracked HVHR projects, the absence of full business cases puts the effectiveness of the state's overarching ILF at risk, because the strategic merit of these projects cannot be fully assessed.

Findings

Implementing past HVHR audit recommendations

DTF has initiated appropriate actions to address all of the recommendations from our 2014 report Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, although further work is still required. In most instances, there have been HVHR process improvements. Nine of the 12 management actions have been completed to date.

DTF and DEDJTR have initiated appropriate actions to address all of the recommendations from our 2015 report Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals. Four of the six management actions have been completed, including the development of a new guideline for market-led proposals by DTF. However, we have not been able to fully assess the effectiveness of DTF's application of this updated guideline because no market-led proposals have been initiated and progressed to negotiation and final contract offer stage since the guideline was updated.

Identifying risks to project deliverability

The HVHR process enables the identification of risks to project deliverability

DTF examines multiple sources of information before the delivery stage of an HVHR project to enable it to identify potential risks to project deliverability. DTF also conducts an assessment and provides advice to government in the earlier stages of the ILF, which means the department is well aware of known risks to project deliverability.

Addressing risks to project deliverability

Quality of performance reporting by departments

Departments report to DTF on their progress with HVHR projects in the Quarterly Asset Investment Report (QAIR), which informs the Major Projects Performance Report to government. The QAIR includes the departments' ratings of project budget and timing risks. DTF has a range of systems and processes in place to gather and scrutinise information on risks during the delivery stage, but is reliant on accurate and transparent reporting by departments in the QAIR. Although departments are able to provide additional commentary in the QAIR, they are not required to report specifically about project risks.

Escalation of significant risks is timely when DTF is on the project-level committee

Significant risks did not materialise for four of the five projects examined in this audit during the delivery stage.

DTF does not participate on all HVHR project-level committees, such as steering committees. It is not clear why some projects receive increased scrutiny and oversight from DTF and others do not. Without clear oversight during HVHR project delivery, DTF cannot be fully assured that risks to project delivery are being identified in a timely manner, project governance arrangements are effective or that progress reports are accurate and reliable. Although DTF assigns analysts to individual projects, interactions between DTF and project teams during the delivery stage is informal and occurs as needed.

In projects where DTF was actively involved in the project-level committee, risks to project deliverability were identified and escalated to the Treasurer in a timely manner, including advice on possible remedial actions and interventions.

Insufficient scrutiny of interdependent project risks

One of the risks with major transport infrastructure projects is that they may rely on the delivery of other infrastructure projects to fully realise their benefits. However, there is poor monitoring of these risks by DTF and relevant agencies.

Although DEDJTR acknowledges that most of the HVHR projects within their area of responsibility have interdependencies, there was no evidence that risks identified in one project were properly managed or overseen as emerging risks for the dependent projects.

DEDJTR advised during the audit that new governance arrangements to manage the risks across the transport portfolio are being considered as part of the establishment of Transport for Victoria.

Fast-tracking of HVHR projects is an emerging risk

In February 2015, the new Victorian Government considered preferred projects for inclusion in its February Economic Statement where planning and project development could be fast-tracked. This included transport-related election commitments that had the potential to be fast-tracked if they were to receive advance funding. The submission to government noted there were higher delivery risks associated with fast-tracking projects that either did not have a completed business case or the business case had not been subject to rigorous project assurance review.

From February 2015, departments were required to develop and submit for HVHR assessment short-form business cases known as 'project proposals' instead of full business cases, as required for all other HVHR projects. Although this ensures a focus on assuring deliverability of these projects, it does not mitigate the investment risks created by the absence of a full business case.

Recommendations

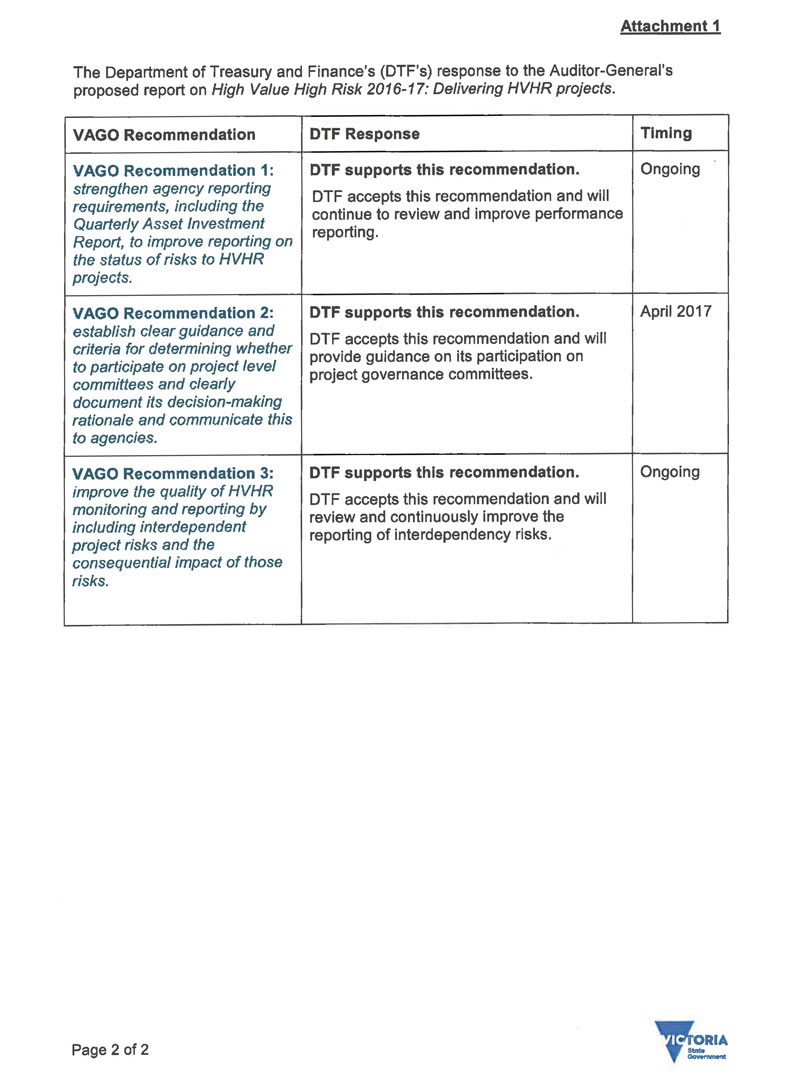

We recommend that the Department of Treasury & Finance:

- strengthen agency reporting requirements, including the Quarterly Asset Investment Report, to improve reporting on the status of risks to HVHR projects (see Section 3.3.2)

- establish clear guidance and criteria for determining whether to participate on project-level committees and clearly document its decision-making rationale and communicate this to agencies (see Section 3.3.3)

- improve the quality of HVHR monitoring and reporting by including interdependent project risks and the consequential impact of those risks (see Section 3.4.5).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with the Department of Treasury & Finance, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, the Department of Health & Human Services, Public Transport Victoria, VicRoads, Monash Health, the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital and the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions.

As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions and comments.

Four agencies provided a formal response. The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

The Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) accepted all of the recommendations in the report. Public Transport Victoria expressed support for the HVHR process, as did the Department of Health & Human Services and Vic Roads who also indicated their continued commitment to work with DTF to improve the delivery of HVHR projects.

We would like to thank the agencies involved in the audit for their cooperation.

1 Audit context

1.1 Introduction

This is our third audit focusing on the effectiveness of the government's 'high value high risk project assurance framework and budget process' (the HVHR process). The goal of the HVHR process is to achieve more certainty about the deliverability of infrastructure projects, including their intended benefits and ability to meet planned costs and time lines.

The key message from our two previous HVHR reports is worth repeating—Parliament and the community rightly expect that publicly funded capital investments are planned and managed in a way that delivers the predicted benefits on time and within allocated budgets. It is critical that the government is fully and reliably informed about projects' costs and benefits, as well as the associated risks, before deciding what projects to undertake.

The government introduced the HVHR process to address systemic weaknesses that undermine agencies' performance in developing and investing in major projects. The consequences of these weaknesses, especially for high value projects, are significant—unexpected cost blowouts affect the government's ability to deliver its wider policy agenda, unforeseen delays mean the community has to wait longer for promised benefits, and unreliable benefit estimates risk distorting government's decision-making.

1.2 Investment in capital projects

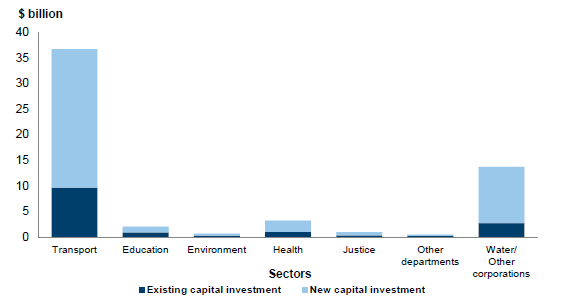

The total estimated investment (TEI) in new and existing capital projects reported in the 2016–17 Budget is $57.7 billion. Around 30 per cent of these projects are being undertaken by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR), primarily because a large number of infrastructure projects are within the transport sector. Figure 1A shows the TEI of new and existing capital investment by sector as reported in the 2016–17 Budget Papers.

Figure 1A

New and existing capital investment, 2016–17 Budget

Note: Transport sector includes Victorian

Rail Track projects.

Source: VAGO, based on the Department of

Treasury & Finance, Budget Paper 4: State Capital Program.

In June 2016, there were more than 450 capital projects in progress, and 41 of these were classified as HVHR. The TEI of these HVHR projects is around $40 billion. They include the Mernda Rail Link, the Drysdale Bypass, the Melbourne Metro Tunnel, the Western Distributor, the Chandler Highway Bridge Duplication, the Level Crossing Removal Program and the High Capacity Metro Trains project.

1.2.1 Legislation and policy

Victoria's investment in infrastructure projects is governed by the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). The FMA requires the principles of sound financial management to be applied by government so as to form a basis for the provision of sustainable social and economic services and infrastructure fairly to all Victorians.

Sound financial management is to be achieved by:

- establishing and maintaining a budgeting and reporting framework

- prudent managing of financial risks, including risks arising from the management of assets

- considering the financial impact on future generations

- disclosing government and agency financial decisions in a full, accurate and timely way.

Other relevant legislation includes the Transport Integration Act 2010 and the Infrastructure Victoria Act 2015. The purpose of the Transport Integration Act 2010 is to create a framework for the provision of an integrated and sustainable transport system in Victoria that contributes to an inclusive, prosperous and environmentally responsible state.

The purpose of the Infrastructure Victoria Act 2015 is to establish Infrastructure Victoria and a new strategic infrastructure planning process in Victoria. Infrastructure Victoria's functions include:

- to prepare and publish a 30-year infrastructure strategy that assesses the current state of infrastructure in Victoria and identifies Victoria's infrastructure needs and priorities for the next 30 years

- to provide support as requested during the development of sectoral infrastructure strategies by public service bodies or public entities, such as the Transport Plan required to be completed under the Transport Integration Act 2010.

In the 2015–16 State Budget, the government committed to fast-tracking infrastructure projects as part of its Getting On With It policy agenda.

1.3 The Investment Lifecycle Framework

The process of planning, proposing and delivering investments is known as the investment lifecycle.

In Victoria, the Investment Lifecycle Framework (ILF) has been established to guide Victorian Government investments. The framework consists of:

- government asset funding processes

- HVHR process

- Gateway Review process (GRP)

- long-term planning

- major projects performance reporting

- investment management standards

- lifecycle guidelines.

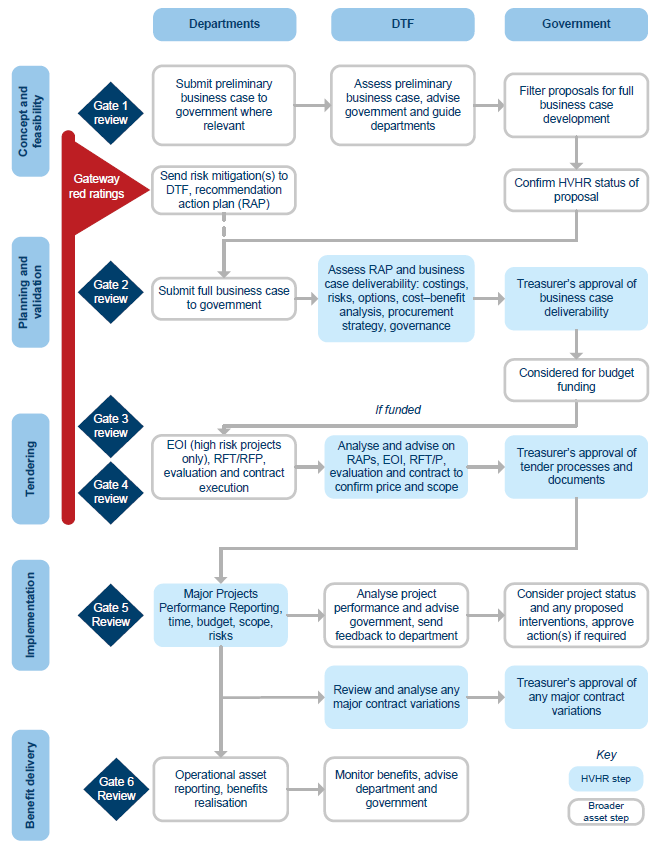

The ILF was developed and is overseen by the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) and is intended to ensure that the state receives maximum benefit from the investment of public money. Figure 1B shows the five stages of the ILF.

Figure 1B

The five stages of the Investment Lifecycle Framework

Source: Department of Treasury and Finance, Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines—Overview (2014).

The ILF aims to make sure that the government:

- addresses the right problems and pursues the right benefits

- chooses the best value-for-money investments

- delivers investments as planned

- realises the benefits it sets out to achieve.

This audit examined the application of the HVHR process during the fourth stage—'Implement' or deliver the solution (delivery).

1.3.1 The HVHR process

In December 2010, the government approved a process for enhanced scrutiny of HVHR asset investments. The HVHR process aims to achieve greater rigour in investment development and oversight, increasing the likelihood of:

- project delivery on time, within budget and to the required quality

- realised benefits for Victorians.

An investment is classified as HVHR if:

- the TEI is greater than $100 million, funded through the Budget process, regardless of funding source; and/or

- the investment is identified as 'high risk' to government using an appropriate risk assessment process; or

- government identifies the investment as warranting extra rigour.

Figure 1C shows the HVHR process for a proposed asset investment by government.

Figure 1C

The HVHR process

Source: VAGO from the Department of Treasury and Finance, High Value High Risk Framework Fact Sheet (2016).

Under the ILF, capital projects identified as being HVHR are subject to more rigorous scrutiny and approval processes by the Treasurer.

The Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines (lifecycle guidelines) provide practical assistance to those proposing investment projects in Victoria and apply to all government departments, corporations, authorities and other bodies falling under the FMA. The lifecycle guidelines also specify the monitoring and reporting requirements, including the provision of the Major Projects Performance Report to government.

Stage 4—'Implement'

Stage 4 of the HVHR process, 'Implement', requires decision-makers to understand whether the solution is the best value-for-money option and that it can be delivered as planned—its 'deliverability'. As shown in Figure 1B, the implement or delivery stage takes the project from the end of the tender stage (when the scope of the project has been defined, a contract has been signed and the costs to deliver the project are known) to project handover (where the asset is available for end users). Key activities during this stage include:

- initiation of construction or development

- contract administration, including progress checkpoints, inspection and pre‑occupancy review

- commissioning and handover.

At stage 4, HVHR projects are subject to closer ongoing oversight by DTF of:

- time, scope and budget reporting and analysis

- governance effectiveness

- risk assessments and mitigation plans

- any recommended interventions and remedial actions.

1.3.2 The Gateway Review Process

The GRP examines projects and programs at key decision points. It is a peer review, in which independent external practitioners use their experience and expertise to examine the project or program's progress and likelihood of success. It aims to provide timely advice to the person responsible for the project or program.

Gateway reviews are applicable to a wide range of programs and projects—policy, infrastructure, organisational change, acquisition and information and communication technology-enabled business changes.

In 2010, GRP became compulsory for all HVHR projects. Figure 1C shows the stages in the ILF and HVHR process when gateway reviews are completed.

1.4 Past VAGO audits

1.4.1 Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects

In the 2014 audit Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects, we found weaknesses in DTF's management of the HVHR process, and with the level of assurance that HVHR scrutiny had lifted practice so it consistently and comprehensively met DTF's better practice guidelines.

We concluded that, although DTF's increased scrutiny made a difference to the quality of business cases and procurements underpinning the government's infrastructure investments, there were gaps in DTF's scrutiny and assurance of HVHR projects.

We made eight recommendations (comprising 12 actions) directed to DTF, to improve the management of the HVHR process. These recommendations included improving the quality of business cases and the consistency, rigour and transparency of the HVHR process by providing better guidance and tools to agencies. DTF developed a management action plan in which it committed to implementing most of the recommendations by June 2015.

1.4.2 Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals

In our August 2015 audit Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals, we found that, in some instances, when the HVHR process was applied to unsolicited proposals, there was inadequate:

- assurance about the deliverability of the proposal's benefits

- assessment of the alternative funding options

- engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts.

We concluded that DTF's guidance fell short of ensuring a rigorous assessment of unsolicited proposals and providing the transparency needed to enable stakeholders and the wider community to understand the full impact of these proposals.

We made three recommendations (comprising six actions) aimed at improving the application of the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals. Two recommendations were directed to DTF and one was directed to DEDJTR.

1.4.3 East West Link Project

In our December 2015 audit East West Link Project, we found that the business case for this HVHR project did not provide a sound basis for the government's decision to commit to the investment. We found that key decisions during the project planning, development and procurement phases were driven by an overriding sense of urgency to sign the contract before the November 2014 state election.

We made six recommendations (comprising nine actions) aimed at improving guidance material for the development of business cases and whole-of-project costing and clarifying requirements for frank, impartial and timely advice in the public sector. Five recommendations (comprising seven actions) were directed to DTF, and one recommendation (comprising two actions) was directed to the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC). DTF and DPC did not accept the recommendations.

1.5 Why this audit is important

'Investment in infrastructure is essential and there is no doubt that in some areas more investment is required. In other areas the amount of money spent on infrastructure does not need to increase, it just needs to be spent more wisely.'1

In the next 30 years, Victoria's population is expected to increase by up to 60 per cent to reach 9.5 million. This rapid population growth presents challenges for our state as new and greater demands are placed on our infrastructure over the coming decades.

DTF's role in providing assurance that the state receives maximum benefit from its investment of public money is critical, especially given the increased level of investment in infrastructure. The scale of government investment and the findings of our previous audits, which identified weaknesses in the application and effectiveness of the HVHR process, are the basis for proceeding with a third audit in this area.

1 Infrastructure Victoria, Victoria's Draft 30-Year Infrastructure Strategy, October 2016

1.6 What this audit examined and how

Our objective was to determine whether the HVHR process has been effectively updated and applied to provide sufficient and reliable assurance about the deliverability of HVHR projects.

To do this, we examined a selection of HVHR projects to determine whether:

- our past HVHR audit recommendations have been addressed by departments in line with management action plans

- the greater level of scrutiny applied by DTF during project implementation has improved the delivery of HVHR projects by better identifying and addressing risks that threaten projects' deliverability.

We asked DTF and DEDJTR to report on their progress in addressing the recommendations from the previous HVHR audits. To determine the effectiveness of their actions to address the recommendations, we examined supporting documents such as guidelines and policies, and tested the effectiveness of actions using a limited sample of relevant HVHR project files.

To test the effectiveness of the HVHR process during project delivery, we selected five HVHR projects. The five selected HVHR projects have a TEI of $914 million and were all in the delivery stage during the audit.

We conducted the audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. In accordance with section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we express no adverse comment or opinion about anyone we name in this report.

The total cost of the audit was $510 000.

1.7 Report structure

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines whether DTF and DEDJTR have addressed the recommendations in our 2014 and 2015 HVHR audits

- Part 3 examines whether DTF's oversight of the HVHR process has improved the delivery of HVHR projects by better identifying and addressing risks that threaten projects' deliverability.

2 Addressing past HVHR audit recommendations

This is our third audit report focusing on the effectiveness of the government's 'high value high risk project assurance framework and budget process' (the HVHR process).

This Part examines whether recommendations from our 2014 and 2015 HVHR audits have been effectively addressed by Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) and Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR).

2.1 Conclusion

DTF has initiated appropriate actions to address the recommendations from our 2014 report, although further work is still required. In most instances, there have been improvements to processes. To date, DTF has completed nine of the 12 management actions.

DTF and DEDJTR have initiated appropriate actions to address the recommendations from our 2015 report. In November 2015, DTF released the new Market-led Proposals Guideline. However, we have been unable to fully assess the effectiveness of DTF's actions in applying the updated guideline because no market-led proposal has been initiated and progressed to the negotiation and final contract offer stage of the process since the update.

2.2 Have the recommendations from the 2014 HVHR audit been addressed?

Our first HVHR audit, Impact of Increased Scrutiny of High Value High Risk Projects (the 2014 HVHR audit), was tabled in June 2014. In this audit we examined the effectiveness of the HVHR process in improving project business cases and procurements so that the project can deliver the intended benefits within approved time lines and budgets.

We concluded that the increased scrutiny DTF has applied through the HVHR process has made a difference to the quality of business cases and procurements underpinning the government's infrastructure investments. However, the improvements had not lifted practices so that they consistently and comprehensively met DTF's better practice guidelines.

The audit also identified weaknesses in DTF's management of the HVHR process, including:

- gaps and inconsistencies in its approach to identifying projects that should be subject to HVHR review

- the need for more comprehensive guidance for HVHR analysts

- inconsistent application of a standardised file structure

- the absence of a comprehensive central register for managing reviews

- the need for better identification and management of potential conflicts of interest.

We made eight recommendations directed to DTF, comprising 12 management actions. Six recommendations aimed to improve the management of the HVHR process, and two recommendations aimed to improve the scrutiny and assurance applied by DTF to HVHR projects.

2.2.1 Progress on actions to improve the HVHR process

Recommendation 1—HVHR project selection

In the 2014 HVHR audit we found gaps and inconsistencies in DTF's approach to identifying projects that should be included in the HVHR process, particularly small value projects that may have high risks, and projects delivered outside the general government sector by public financial and non-financial corporations, water corporations and alpine resorts.

We had already identified this issue in our 2013 audit of the gateway review process where we found that DTF did not effectively monitor departments' compliance in applying the risk assessment tool—the Project Profile Model (PPM). Figure 2A summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2A

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

1 |

That DTF improve its approach to selecting projects for inclusion in the HVHR process by: |

||

1(a) |

|

DTF will expand the application of the Project Profile Model (PPM) to make it mandatory for all projects above $5 million, to ensure that there is a documented rationale behind HVHR project designation. DTF will use the PPM to inform its assessment of individual project's risk profiles and whether the HVHR framework will be applied. |

✔ |

1(b) |

|

DTF will develop criteria to inform its advice to government on this matter. |

✔✔ |

1(c) |

|

DTF will review the Unsolicited Proposal Guideline and provide advice to government on how the HVHR process can be applied to unsolicited proposals. |

✔✔ See 2.3 |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has not fully completed actions to address recommendation 1(a). Although it is now mandatory for a PPM to be completed for projects over $5 million, DTF has not implemented an effective approach to monitor compliance with this requirement.

DTF has addressed recommendation 1(b). The department briefed the Treasurer in May 2016 and implemented changes to the HVHR criteria in July 2016. The brief also foreshadowed a wider update of both the gateway review and HVHR processes, including any changes needed once the proposed new Office of Projects Victoria becomes operational. From July 2016:

- the total estimated investment (TEI) threshold of $100 million only applies to projects funded through the Budget process

- projects that are not funded in the Budget are only included in the HVHR process on a risk basis

- only projects assessed at the business case stage as having an Expression of Interest (EOI) process rated as high risk, such as alliance models and public private partnerships, require the Treasurer's approval for release of EOI documents

- Tender Assessment and Contract Award stages will be merged to form one Treasurer's approval stage (stages 3 and 4).

DTF has addressed recommendation 1(c) by updating its guidelines in August 2014. However, the 2015 HVHR audit found that there were weaknesses in the implementation of this recommendation, including a lack of comprehensive analysis of the risks and issues relating to the completion of HVHR assessments of unsolicited proposals. We made a further recommendation to address these weaknesses, which is examined in our assessment of DTF's actions taken in response to the 2015 HVHR audit (see Section 2.3).

Recommendation 2—assessment guidance and templates

In the 2014 HVHR audit we identified the need for DTF to develop comprehensive internal assessment guidance. Achieving consistent, rigorous reviews across multiple HVHR projects represented a significant challenge for DTF, which could be better addressed with review templates covering every stage of the HVHR process. Figure 2B summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2B

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

2 |

That DTF develop assessment guidance and templates covering all HVHR stages to improve the consistency, rigour and transparency of HVHR reviews. |

DTF will develop guidance and templates for all HVHR approval gates. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 2. It has developed guidance and templates for all HVHR approval gates.

The updated guidance includes a list of the sources of information that analysts should use to assess business cases and requires them to consider the lessons learnt from past gateway reviews. The template includes additional criteria for market-led proposals and for information and communication technology (ICT) projects.

DTF has also developed internal guidance and assessment templates for evaluating tender documentation, the preferred bid and contract, and contract variations. We found that the assessment criteria in these templates aligned with the Investment Lifecycle Framework (ILF) and HVHR guideline requirements.

Although we were satisfied that DTF had addressed this recommendation, we found that it has not developed assessment guidance and templates for the preliminary business case stage, which requires DTF assessment.

Often referred to as stage 0 of the ILF, the preliminary business case stage is specific to HVHR projects. It assesses whether projects present a compelling case for the government to invest and should be prioritised for government funding consideration.

The HVHR process was originally introduced to provide more certainty of project costing, timing and benefits. The preliminary business case stage was introduced to confirm there is a service need or problem that needs to be addressed before significant investment in business case development.

Recent changes to the HVHR process have limited the preliminary business case requirements to proposals submitted during stage 1 of a two-stage Budget filtering process. A single-stage Budget process was used for the 2015–16 Budget process, and DTF did not formally assess preliminary business cases.

Recommendation 3—HVHR central file system

In the 2014 HVHR audit we found that DTF's existing file system for HVHR projects was not consistently applied, standardised, or easy to navigate. The lack of a structured and consistent approach to record keeping made it more difficult for DTF to assess HVHR reviews and to respond in a timely manner. Figure 2C summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2C

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

3 |

That DTF improve its administration of the HVHR process by: |

||

3(a) |

|

DTF will ensure that its existing standardised file structure, which contains guidance material for analysts, templates, completed assessments, supporting evidence and documentation, is consistently and fully applied. |

✔✔ |

3(b) |

|

DTF will continue to implement and further develop its existing central register of HVHR review activity. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendations 3(a) and 3(b). It has developed a standardised file structure for managing project documentation, including HVHR assessments. It has expanded the information captured in its central register to include tracking of agencies' actions to address recommendations from gateway reviews that received a red rating ('urgent' or 'critical').

Recommendation 4—continuous improvement

In our 2014 HVHR audit we identified that periodic reporting on progress and emerging lessons was critical to realising the potential of the HVHR process. We found that DTF was managing HVHR reviews on a project-by-project basis. DTF was not communicating key lessons across the sector and did not have a structured way to understand and learn from agencies' experiences of the HVHR process because it did not formally survey them. Figure 2D summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2D

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

4 |

That DTF improve how it communicates with and informs departments by: |

||

4(a) |

|

DTF will develop and implement a formal approach to collating and sharing lessons learnt from HVHR reviews across the sector |

✔✔ |

4(b) |

|

DTF will develop a process where agencies are asked for feedback on their experience of the HVHR process. |

✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 4(a), and has commenced, but not completed, activities relating to 4(b). DTF periodically shares lessons learnt with the relevant agencies though the Infrastructure Policy Reference Group (IPRG) and periodically updates HVHR guidance material. DTF has prepared a draft annual satisfaction survey form, but it has not yet undertaken a survey of agencies involved in the HVHR process, even though the process was adopted more than five years ago.

We note that DTF considers that its current review and update of the HVHR policy supersedes the need for a survey, and provides a more comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the framework.

Recommendation 5—conflicts of interest

In the 2014 HVHR audit we found that there was a potential conflict of interest in DTF's role as both contributor to and assessor of business case submissions. This issue had also been raised by other bodies, such as Ombudsman Victoria and the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee. Figure 2E summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2E

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

5 |

That DTF identify potential conflicts of interests of reviewers, and documents how these are mitigated. |

DTF will enhance its HVHR guidance to clarify the various roles that DTF officers have in relation to different stages of the project lifecycle. |

✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has not fully addressed recommendation 5. It has updated documentation to include the potential for conflict, but this content relates to conflicts of interest within the agency and project teams. It does not refer to the conflicting roles of DTF representatives who sit on steering committees or project boards and also advise government about a project's performance.

DTF guidance material states that perceived conflicts of interest of DTF's HVHR reviewers should be mitigated by the multiple sign-off stages in the HVHR approval process before a proposal is submitted to the government.

Recommendation 6—evaluation of the HVHR process

In the 2014 HVHR audit we found that, although DTF had committed to undertaking an independent evaluation of the HVHR process and reporting the results to the government by June 2014, this review had not occurred. DTF had not developed an evaluation framework and had not collected and processed the data needed to measure the outcomes of the HVHR process. Figure 2F summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2F

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Management of the HVHR process |

|||

6 |

That DTF develop and apply an evaluation tool to measure the extent to which the HVHR process is affecting project outcomes. |

DTF will commit to developing an evaluation tool which measures the extent to which the HVHR process is improving project outcomes, and which takes into account outcomes from this report, as well as lessons learnt from other HVHR projects. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 6. DTF commissioned a review to measure the effectiveness of the HVHR process, using two equally weighted performance measures. The review assessed:

- whether HVHR processes have resulted in better planned, articulated and delivered projects, using gateway and DTF project ratings before and after the introduction of the HVHR process

- whether DTF's review and approval processes identified impact factors and reduced the risk of these occurring, using interviews with stakeholders for selected projects and assessments by DTF that informed the Treasurer's decision.

This review concluded that the HVHR process had resulted in better planned and delivered projects, but it had limited access to project-specific information. The review found that the HVHR framework did not help to mitigate risks across the project lifecycle and that the impact of the HVHR process after procurement is limited to project reporting mechanisms.

2.2.2 Progress on actions to improve the quality of reviews

Recommendation 7—assurance of project deliverability

In the 2014 HVHR audit we found that DTF performed strongly when examining project costs, time lines and agencies' approaches to risk management contained in business cases. DTF's performance was mixed when it examined procurement, governance and project management, and clearly inadequate when it examined expected project benefits. Figure 2G summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2G

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Improving the quality of reviews |

|||

7 |

That DTF provide greater assurance that HVHR reviews comprehensively test compliance with its investment lifecycle and HVHR guidelines in areas critical for project deliverability. |

DTF will commit to continuously improving the HVHR guidelines and will continue to refine HVHR processes to ensure they are aligned to appropriate sections within the Investment Lifecycle Guidelines. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 7. It has amended the assessment template for business case deliverability and implemented a new assessment template with guidance to assess projects during the procurement phase.

Recommendation 8—project team capability

In the 2014 HVHR audit we tested a business transformation project that included changes to a business process and the supporting ICT systems.

We found that there were critical gaps in the project's management, oversight and governance, and independent review. In particular, this independent review did not detect and respond to the risks inherent in this type of project. This meant that DTF's management and oversight of the project did not effectively identify and control risks before they materialised, which caused delays and increased delivery costs.

Our March 2016 audit report, Digital Dashboard: Status Review of ICT Projects and Initiatives – Phase 2, also identified the need for senior management and ICT specialists to actively engage in these sorts of projects. Figure 2H summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2H

Status of the 2014 HVHR recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Improving the quality of reviews |

|||

8 |

That DTF checks that for complex, risky projects—particularly those involving information and communications technology transformations—the specialist skills needed to successfully manage, oversee and quality assure these projects have been assessed and acquired. |

DTF will increase the emphasis on reviewing and providing advice on project team skills and expertise where appropriate. This should not diminish in any way the line department's accountability in project delivery. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 8. The criteria used to assess the deliverability of ICT transformation projects have been expanded to include a requirement for project governance arrangements to include independent ICT specialists, as well as additional assurance mechanisms such as ICT audits.

2.3 Have the recommendations from the 2015 HVHR audit been addressed?

Our second HVHR audit, Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals, was tabled in August 2015. In this audit we assessed whether the HVHR process had been effectively applied to unsolicited proposals identified as HVHR projects, now referred to as market-led proposals.

We concluded that DTF had not consistently and comprehensively applied the HVHR process to market-led proposals. DTF's guidance did not ensure a rigorous assessment of the likely benefits of market-led proposals and did not provide the transparency needed to enable stakeholders and the wider community to understand the full impact of these proposals.

We also found that, in some instances, the application of the HVHR process to market-led proposals provided:

- weak assurance that the proposal's benefits could be delivered

- inadequate assessment of alternative funding options

- inadequate engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts.

We made three recommendations, comprising six management actions. Two recommendations were directed to DTF, aimed at improving the guidelines for market-led proposals and the transparency of proposal evaluations. One recommendation was directed to DEDJTR, to evaluate the effectiveness of the recently introduced transport forecasting and economic appraisal governance framework.

Although DTF updated the guidelines for market-led proposals in November 2015, no market‑led proposal has been initiated or progressed to negotiation and final contract offer stage of the market-led proposal process since then (for example, the proposal for the Western Distributor was developed under the previous guidelines). Therefore, we have not been able to test DTF's application of these updated guidelines on a market-led proposal.

2.3.1 Progress in reviewing market-led proposal guidelines

Recommendation 1—information transparency

In our 2015 HVHR audit we highlighted that private-sector proponents sponsoring market-led proposals are likely to be focused on their own commercial interests. As a result, they may be wary of investing too much up front, when it is uncertain whether the government will support their proposal. Specifically, proponents are more likely to focus on costs, risks and timing of the delivery of planned outputs and have a limited focus on understanding, defining and realising service outcomes (or benefits) that are critical to the community. Figure 2I summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2I

Status of the 2015 HVHR audit recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Advice and guidelines on applying the HVHR Process |

|||

1 |

That DTF review the current market-led proposals guideline and advise government how to: |

||

1(a) |

|

DTF will revise the Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline for the Government to consider. The revisions will aim to provide greater clarity on information to be provided by proponents. The revisions will aim to outline the type of due diligence done by departments to inform high value high risk assessments at each stage. |

✔✔ |

1(b) |

|

DTF will include a template project summary in the Revised Market-led Proposal Guideline. The addition of a template will provide further detail on the assessment process and proposal outcome to be publicly disclosed. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendations 1(a) and 1(b).

In November 2015, the revised Market-led Proposals Guideline was released, which requires more comprehensive information to be included in proposals submitted to the government. This includes content on the investment rationale and likely benefits, details of any stakeholder consultation undertaken, and clarification of the roles of the private proponent and relevant public sector departments through the market-led proposal stages.

Due diligence processes are also outlined in the new guideline, including the project options that have been considered, the financial impact on the government, a stakeholder plan, and the government's rationale for approving the market-led proposal. This information will be presented as a Project Summary and released on DTF's website within 90 days of the contract being awarded.

2.3.2 Progress in improving scrutiny of proposals

Recommendation 2—transport modelling governance framework

The 2015 HVHR audit found that DEDJTR had only recently put a governance framework in place to ensure that robust and consistent assumptions underpinned its transport modelling and economic appraisal of projects, and that these assumptions have been properly applied. Consequently, we could not test the governance framework at the time of the audit. Figure 2J summarises the recommendation, DEDJTR's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2J

Status of the 2015 HVHR audit recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Scrutiny applied to proposals |

|||

2 |

That DEDJTR evaluate the effectiveness of the governance framework used to assure the quality of transport forecasts and economic appraisals. |

DEDJTR will complete an initial evaluation of the effectiveness of its governance processes by March 2016. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DEDJTR has addressed recommendation 2. An external review of the governance framework was finalised in March 2016. The review found that the new model governance structure is ensuring consistency in project modelling and appraisal methods across projects. The review recommended that the effectiveness of the governance structure be evaluated in the next two years.

The review also noted DEDJTR's positive step in producing new guidelines to ensure consistent modelling and appraisal methods across projects. However, the review raised concerns that other agencies have developed guidelines and recommended that DEDJTR consider amalgamating them into one guideline for consistency. DEDJTR expects these concerns to be addressed through the establishment of Transport for Victoria, when modelling activities will be brought more closely together.

Recommendation 3—benefits realisation

In the 2015 HVHR audit, we found weaknesses in the level and depth of scrutiny DTF applied to verify the benefits of unsolicited proposal submissions, including the impact of uncertainties and critical risks to these benefits. There was also insufficient information on the full costs and impacts on stakeholders, and stakeholder consultation was undertaken after most of the significant decisions had been made. Figure 2K summarises the recommendation, DTF's response and the current status of actions.

Figure 2K

Status of the 2015 HVHR audit recommendations

Number |

Summarised recommendation |

Response |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|

Scrutiny applied to proposals |

|||

3 |

That DTF: |

||

3(a) |

|

DTF will revise the Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline for the government to consider. The revisions will aim to outline the type of due diligence done by departments to inform high value high risk assessments at each stage. |

✔ |

3(b) |

|

On a case-by-case basis, depending on the type of proposal and whether government funding is associated with the proposal, a business case may be built up to verify the costs and benefits. Investment Lifecycle Guidelines require business cases to analyse funding options. |

✔ |

3(c) |

|

The guideline revisions will include a new requirement that departments develop a stakeholder engagement strategy for the government to consider. |

✔✔ |

Note: ✔ =

commenced, ✔✔

= completed.

Source: VAGO.

DTF has addressed recommendation 3(c). Although actions to address recommendations 3(a) and 3(b) have commenced, they cannot be tested because no new proposals have been initiated and progressed to negotiation and assessment of final offer stage of the market-led proposal process under the new guidelines.

We examined the new guidelines and found that they:

- place greater emphasis on project benefits and the risks to those benefits, and require proposals submitted for evaluation to include information on the investment rationale and the benefits that are likely to be realised from the proposal

- include requirements for proposals that need government funding to submit an interim business case at stage 3 (detailed due diligence, investment case and procurement preparation) of the proposal and a final business case at stage 4 (negotiation and assessment of final offer).

The new guidelines also require a stakeholder engagement plan to be developed for all proposals that progress to stage 3 of the process. The plan must include details on key impacts of the proposal on stakeholders, and specify the responsibility for consultation and the stage of the project at which the engagement will take place.

3 Oversight of HVHR projects during delivery

In this Part we examine the Department of Treasury & Finance's (DTF) role during the delivery stage of the 'high value high risk project assurance and budget process' (the HVHR process). We assessed DTF's approach to monitoring and overseeing project risks, focusing on five HVHR projects that were in the delivery stage during the audit.

The five projects are shown in Figure 3A, including the department responsible for the project and the total estimated investment (TEI). The responsible departments are the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) and the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS).

Figure 3A

Summary of HVHR projects selected for this audit

|

Project |

Description |

Department responsible |

TEI(a) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dingley Bypass(b) |

The construction of a 6.4 km section of arterial road linking Warrigal Road at Moorabbin and Westall Road at Dingley Village. The road will be three lanes wide in each direction, with an adjacent shared cycle and pedestrian path. |

DEDJTR |

$156m |

|

Regional Rolling Stock(c) |

The procurement of carriages for the regional rail network. |

DEDJTR |

$251m |

|

Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Electronic Medical Record ICT (b) |

An ICT project to implement a clinical electronic medical record system. |

DHHS |

$48m |

|

Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital Redevelopment |

A mix of new build and refurbishment of existing facilities, including the construction of new connecting link bridges, providing five integrated and future-proofed floors and an upper-level training, teaching and research facility. |

DHHS |

$201m |

|

Monash Children's Hospital |

A new hospital based in Clayton, providing 230 beds within a dedicated child and family-friendly paediatric environment. |

DHHS |

$258m |

(a) The TEI listed may include funding from other sources. Figures have been rounded.

(b) The Dingley Bypass and the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Electronic Medical Record ICT project are listed as completed in Budget Paper 4 (2016–17). We have used the TEI from Budget Paper 4 (2015–16).

(c) Regional Rolling Stock is listed in Budget Paper 4: State Capital Programs as a Victorian Rail Track (VicTrack) capital investment.

Source: VAGO based on information from the Department of Treasury & Finance, Budget Paper 4: State Capital Program 2016–17.

DTF is required to exercise closer oversight of HVHR investments throughout the project implementation or delivery stage, focusing on:

- time, scope and budget reporting and analysis

- governance advice and monitoring

- risk assessment and mitigation reviews

- any recommended interventions or remedial actions.

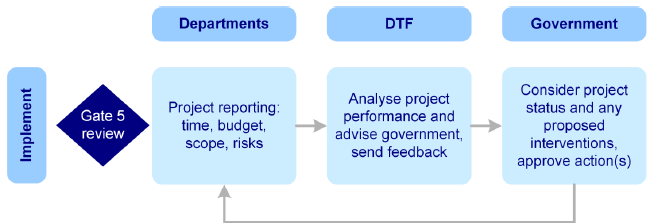

Figure 3B shows the responsibilities of departments, DTF and the government during the delivery stage of an HVHR project.

Figure 3B

Responsibilities during HVHR project delivery

Source: The Department of Treasury and Finance, Investment Lifecycle and High Value/High Risk Guidelines—Implement, 2012.

3.1 Conclusion

DTF has sufficient information to monitor risks to the deliverability of HVHR projects. However, it relies on timely and accurate reporting by agencies, particularly when DTF is not represented on project-level steering committees. This means DTF cannot be fully assured that risks to project delivery are being identified in a timely manner, project governance arrangements are effective, or that progress reports on the project's delivery are accurate and reliable.

Significant implementation risks did not materialise for most of the projects we examined in this audit, and DTF advised the Treasurer in a timely manner about significant risks and possible remedial actions and interventions.

However, DTF and departments did not sufficiently consider and monitor interdependent investment risks, particularly for HVHR projects in the transport sector, where some projects rely on the delivery of other projects. Because monitoring and reporting activities are largely focused on individual projects, these interdependent project risks are not being effectively managed or monitored.

The absence of full business cases for fast-tracked HVHR projects risks limiting the effectiveness of the state's Investment Lifecycle Framework (ILF) because the strategic merit of these projects cannot be fully assessed.

3.2 Identifying risks to project deliverability

Understanding a project's deliverability involves detailed planning of its costs, key sources of uncertainty, time lines and critical dependencies.

3.2.1 Project risks

DTF examines multiple sources of information before the delivery stage of an HVHR project, enabling it to identify potential risks to project deliverability.

These sources of information include:

- HVHR assessments—business case deliverability, and contract and procurement

- project business cases

- risk management plans

- information on critical recommendations from gateway review reports

- procurement strategies

- the Quarterly Asset Investment Report (QAIR)

- the Major Project Performance Report (MPPR)

- lessons learnt from past HVHR and gateway reviews.

DTF's access to these information sources, and the assessment and advice provided to government in the earlier stages of the ILF, mean that DTF has a good understanding of the known risks to project deliverability.

Business case deliverability assessments

HVHR business case deliverability assessments (deliverability assessments) evaluate a project's ability to be delivered on time and on budget and to achieve the stated benefits.

DTF completes deliverability assessments during stage 2 of the investment lifecycle (known as 'Prove'—see Figure 1B). These assessments consider the proposed solution, the impact of the project, the risk management approach, the governance structure, the approach to procurement and the project management strategy.

We examined the deliverability assessments for the five selected HVHR projects. For four of the five HVHR projects, deliverability assessments were completed in 2012. This means that, at the time of our audit, DTF had known of risks to the deliverability of these projects for more than three years. DTF had identified the following key risk areas for the selected projects:

- project impact

- business case

- delivery to budget and time lines

- stakeholders and communication

- governance

- solution delivery.

DTF originally assessed three of the five projects examined as not meeting the deliverability requirements. One project, the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Electronic Medical Record project (RCH ICT project), was granted conditional approval, and the other two were reassessed eight months later and subsequently approved. For each of these projects, DTF's decision to subsequently approve the deliverability assessment was accelerated by time line pressures.

The case study in Figure 3C highlights how a business case deliverability assessment was used in the RCH ICT project, to address project risks prior to delivery.

Figure 3C

Case study—Deliverability assessment: conditional approval

|

We found that the conditional approval of the RCH ICT project was an appropriate response. DTF was clear in their deliverability assessment that the project business case was not sufficiently robust to be approved, but that if the government were to grant approval, it should be with conditions attached, and the project should be monitored under the HVHR process. DTF attached conditions to business case costings, risk management, procurement and governance. Improved governance conditions included:

These conditions enabled DTF to work with the project team to address issues and risks, and to make sure that conditions were actioned before the tender decision was made. They also resulted in strengthened governance arrangements, including the formation of an ICT Assurance Board that included senior DTF and DHHS representation. |

Source: VAGO.

3.3 DTF's oversight and monitoring of HVHR project risks during delivery

HVHR guidelines state that, during the implement or delivery stage of the HVHR process, DTF analysts should:

- 'assist project teams to report and monitor progress

- provide regular advice to government every six to eight weeks on project time and budget status, risks and any recommended interventions

- participate in steering and other project committees where feasible or appropriate'.

3.3.1 High Value High Risk Assurance Committee

The key governance body within DTF that monitors the progress of HVHR projects is the High Value High Risk Assurance Committee (HVHRAC). This committee was established in 2013, originally as a subcommittee of the DTF board, and is now a standalone committee. Its functions are to:

- review and endorse policies relating to the HVHR framework

- oversee the effective implementation of the HVHR project assurance framework across DTF

- oversee the asset investment and major project reporting process

- review the gateway review process

- review asset investment reports on behalf of the DTF board and report any issues to the board.

HVHRAC meets quarterly to consider the drafts of the (MPPR)—see Section 3.3.4. It also selects a small number of projects—usually four or five—for more detailed discussion. In finalising the MPPR, HVHRAC considers whether issues and risks facing HVHR projects need to be escalated to the Treasurer, including identifying any interventions and remedial actions to be recommended to government. It also identifies systemic HVHR project issues and lessons learnt from past HVHR projects.

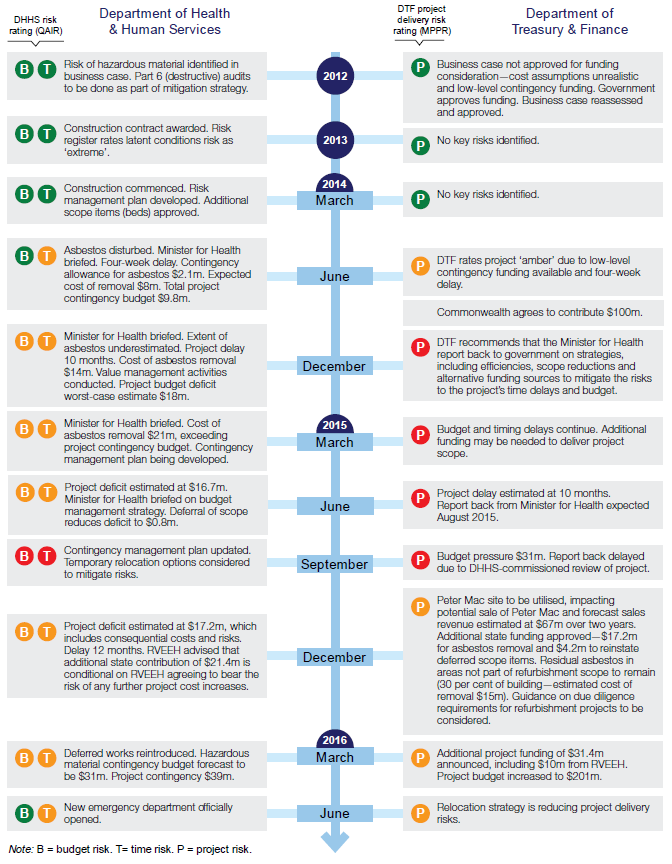

DTF provides advice to the Treasurer in the MPPR, including recommending that government request relevant ministers report back on progress in addressing specific risks to HVHR projects. For example, in the December 2014 MPPR, the Minister for Health was requested to report back to government on the strategies—including efficiencies, reductions of scope and alternative funding sources—to mitigate the risks of delays and budget issues in the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital (RVEEH) redevelopment.

3.3.2 Agency reporting to DTF

Departments report to DTF on HVHR project progress in the QAIR. Departments report on all asset investments in Budget Paper 4: State Capital Program, not just HVHR projects. It is a performance-monitoring requirement under the Financial Management Act 1994.

The QAIR includes the department's rating assessment of a project's budget and timing risks. It also includes budget and timing data, such as the TEI, the budget per quarter and the forecast end date. Departments are also able to provide additional commentary, which is an opportunity for them to highlight risks and issues, but there is no requirement to report specifically on project risks.

The QAIR is a key source of information that DTF uses to inform the development of the MPPR. Departments rate budget and timing risks in QAIR as green, amber or red. Figure 3D shows the risk assessment criteria used by departments to determine the risk rating.

Figure 3D

QAIR risk assessment criteria

|

QAIR rating |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Green |

On schedule |

|

Amber |

Project risks are emerging that could affect delivery—the project is likely to miss a significant milestone or there are scope or contract variations |

|

Red |

More than 10 per cent behind the approved schedule/budget |

Source: VAGO.

Figure 3D shows that departments rate a project as amber when emerging risks are identified. DTF and departments rely on project agencies to report accurately and transparently in QAIR. We found that DHHS knew that the budget and time lines for the RVEEH redevelopment were expected to be exceeded by more than 10 per cent but continued to rate the risk as amber—an emerging risk—while they conducted value management exercises. The time line of events is outlined in Figure 3H.

The finance area within relevant departments verifies the financial information in the QAIR, and the secretary approves it, before it is submitted to DTF. DTF also seeks further explanation from departments if the financial information does not match its records.

3.3.3 DTF's role on project steering committees

Beyond the HVHRAC and QAIR reporting, DTF's other primary means of monitoring HVHR project risks is to participate on project-level committees, typically project steering committees. This enables DTF to have much greater oversight of risk management and emerging project risks, as well as assurance that HVHR projects are being delivered as planned.

As there are no mandatory Treasurer's approval steps after a contract has been awarded, formal scrutiny of projects by DTF during delivery is not mandated as part of any approval processes. DTF is only required to formally scrutinise an HVHR project during delivery if an agency requests a significant contract variation to address project risks, as these variations must be approved by the Treasurer.

According to HVHR guidelines, DTF does not have to be represented on project steering committees. However, when the government approved the HVHR process, the Treasurer's submission stated that DTF would have continuing involvement with HVHR projects through membership of project steering committees or boards.

DTF does not participate on all HVHR project-level steering committees. Without clear oversight during the implementation of HVHR projects, DTF cannot be fully assured that project governance arrangements are effective, that risks to project delivery are being identified in a timely manner, or that progress reports on the project's delivery are accurate and reliable. Although DTF assigns analysts to individual projects, DTF's interactions with project teams during delivery are less formalised and occur only as required.

When DTF is active on project steering committees, we found that risks to project deliverability were identified and escalated to the Treasurer in a timely manner. In the case of the RVEEH redevelopment project, asbestos issues affected the delivery stage. DTF escalated the emerging risk to government soon after it became aware of the risk. If DTF was not on the steering committee and relied solely on the department's reporting, it may not have been able to escalate the risk to government as early as it did.

DTF is presently a member of around 60 per cent of HVHR project-level committees. Figure 3E shows whether the portfolio department and DTF are members of the HVHR project-level committees, such as steering committees, for the audited projects.

Figure 3E

DTF and portfolio department membership on HVHR project-level committees

|

Project |

Portfolio department |

Is the portfolio department on the project-level committee? |

Is DTF on the project-level committee? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dingley Bypass |

DEDJTR |

No |

No |

|

Monash Children's Hospital |

DHHS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Regional Rolling Stock |

DEDJTR |

No |

No |

|

Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Electronic Medical Record ICT |

DHHS |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital redevelopment |

DHHS |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: VAGO.

For two of the five audited projects, neither the portfolio department nor DTF are members on project-level committees. For the Monash Children's Hospital and the RVEEH redevelopment, DHHS—the portfolio department—is also the project manager. DEDJTR is the portfolio department for the Dingley Bypass and Regional Rolling Stock (RRS) projects, but the projects are managed by VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria (PTV) respectively. DHHS is the portfolio department for the RCH ICT project but the project is managed by the health service.

DTF is also represented on portfolio and sector-level committees that receive information on HVHR project progress, including any major risks to project deliverability.

Although DTF and DEDJTR are not members of the project-level committees for the transport-sector projects we audited, the departments are members of the Transport Infrastructure Policy, Planning and Delivery Committee (TIPPD), which also includes representatives from the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC), PTV, VicRoads and Major Projects Victoria. There is a role for sector-level infrastructure committees such as TIPPD and the Health Capital Projects Board (HCPB), but they do not, on their own, allow DTF to identify and escalate emerging project-specific risks in a timely manner.

When an HVHR project has a lower risk profile and could be considered 'business as usual', except that the project is valued in excess of $100 million, it may be appropriate for DTF not to participate on project-level committees. This was the case for the Dingley Bypass project—DTF's deliverability assessment noted that it was a standard project for VicRoads, with no procurement issues. Having participated on similar projects in the past, DTF determined that its participation on the project steering committee was not necessary.

For the other projects we examined, the reason for DTF's lack of participation was less clear. In the case of the RRS project, DTF identified that there was appropriate senior management representation on the project steering committee, but intended to seek membership. For other projects, we found that DTF had opted to wait for an invitation or had no rationale for why it did not need to participate on the project steering committee.

DTF should have a clear, documented and robust rationale for instances where it does not participate on project steering committees. It should assure itself that risks are being managed appropriately without the need for any additional oversight or monitoring.

3.3.4 Major Projects Performance Report

DTF reports on HVHR project progress and risks to the Treasurer via the quarterly (MPPR). This report makes recommendations on appropriate interventions or remedial actions, informs government about emerging risks and issues in the delivery of major projects, and reports on the performance of departments in managing project delivery risks. The number of HVHR projects being monitored and reported in the MPPR has doubled since the HVHR process began.

The MPPR provides an assessment of HVHR project progress in terms of time, scope and budget. We examined the changes in time and budget for the five audited HVHR projects, as shown in Figure 3F.

Figure 3F

Changes in time and budget for selected projects

|

Project |

Change from original end date |

Change from original budget |

Reason for change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dingley Bypass |

–6 months |

No change |

Delivered early |

|

Monash Children's Hospital |

No change |

+$8m |

Additional scope for helipad and research wing—additional funding provided by the state, health service and external sources |

|

Regional Rolling Stock |

No change |

–$10m |

2015–16 Budget—to fund X'Trapolis trains |

|

Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Electronic Medical Record ICT |

No change |

+$24m |

$24 million provided by RCH to deliver preferred ICT solution |

|

Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital Redevelopment |

+12 months |

+$36m |

Removal and management of hazardous material, reinstatement of deferred scope, additional scope—Education Centre—funded by the state and health service |

Source: VAGO.

To date, only the Dingley Bypass and the RCH ICT project have reached practical completion, with the Dingley Bypass being delivered ahead of time and within budget. The three health service projects each received additional funding at varying stages after the initial budget commitment was made.

In MPPR reports, DTF and DPC (central agencies) assess HVHR project risks as green, amber or red, as shown in Figure 3G.

Figure 3G

MPPR risk assessment criteria

|

MPPR rating |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Green |

|

|

Amber |

|

|

Red |

|

Source: VAGO.

Figure 3G shows that the trigger for DTF to recommend interventions or remedial action is a red risk rating.

In the five audited projects, four were rated green by both the department and central agencies in each quarter during delivery. Only one of the five projects—the RVEEH redevelopment—received a rating other than green during this stage. Central agencies rated this project as red for four consecutive quarters.

3.4 Case study projects

3.4.1 Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne ICT project

DTF is not a member of the project steering committee and receives information on the project through its representation on the Royal Children's Hospital Electronic Medical Record Program Assurance Board (the assurance board), and through quarterly reporting processes. The project steering committee and the assurance board are provided with risk assessment and treatment plans, which clearly show the status of risk treatments, how effective the mitigation strategies have been and the monitoring activity undertaken.

The identified major risks to this project during delivery included:

- customisation of the new ICT system to meet Australian requirements

- system integration risks—the new ICT system and existing applications

- insufficient organisational readiness to implement the new ICT system arising from change management processes failing to keep pace with the implementation time frames.

- previous demand levels in outpatient clinics not being met

- clinical claims arising post implementation due to insufficient use of the system.

An examination of the meeting minutes and papers of the assurance board show that there was continuous discussion and monitoring of key project risks, including the risks relating to customisation of the new ICT system to meet Australian requirements and the system integration risks. There was also coverage of organisational change management, including the risks associated with staff training and logistics.