Implementation of School Infrastructure Programs

Overview

Between 2007 and 2012, $4.5 billion was invested in Victorian Government schools through two major infrastructure programs: the state-funded Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Commonwealth-funded Building the Education Revolution (BER) program.

These programs saw building works take place at 93 per cent of government schools, and correspondingly the majority of school buildings are currently in a functional condition. However, critical issues with the school building portfolio and the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s (DEECD) management of it remain. More than 5 000 individual buildings are below DEECD’s accepted standard, requiring further investment of $420 million to address this. There is a considerable surplus of building space across the portfolio—38 per cent according to current enrolment levels. A legacy of underfunding schools to maintain buildings, and lack of accountability for their doing so means that there is a genuine risk that those buildings developed through VSP and BER will not be adequately maintained, undermining the benefit of this major investment in government schools.

Furthermore, DEECD has not comprehensively evaluated the implementation and the impact of VSP or BER—a significant missed opportunity to identify and leverage the lessons from these significant programs. DEECD’s lack of long-term strategic asset planning for school buildings also compromises its ability to manage the portfolio efficiently and effectively. However, it is positive that DEECD is taking steps to develop such a plan.

Implementation of School Infrastructure Programs: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2013

PP No 213, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Implementation of School Infrastructure Programs.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

20 February 2013

Audit summary

Prior to the Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Building the Education Revolution (BER) programs, the government school portfolio comprised 1 597 schools with a combined land and building value worth $10.7 billion. As a result of VSP and BER, the value of the portfolio has increased by 27 per cent to $13.9 billion, and through mergers and consolidations, there are now 1 537 schools.

The government school portfolio is one of the largest state-owned asset portfolios, accounting for almost 13 per cent of the Victorian Government’s total asset base. More than 63 per cent of all school students in Victoria attend a government school and managing these buildings effectively is essential to providing a quality education to these students.

Conclusions

Between 2007 and 2012, VSP and BER invested $4.5 billion in Victorian Government school infrastructure. This led to 93 per cent of government schools undertaking some type of capital works.

While some quality concerns have been expressed, and some individual projects were difficult, these two major infrastructure programs have broadly been delivered on time and on budget. Due to this investment, the majority of government school buildings are now in satisfactory operational condition, with 67 per cent of all buildings recently assessed as being in good or excellent condition.

While this is a positive result, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has not evaluated these programs in a comprehensive and timely manner and it may have missed an opportunity to apply the lessons learned from these programs to improve its asset management practices.

Also, despite this significant investment, major issues still exist within the school building portfolio and DEECD’s asset management processes. In particular, DEECD needs to address the ongoing underfunding of school maintenance and the limited accountability across schools for the efficient, effective and economic use of maintenance funds.

These issues are not new. This area has been subject to a number of DEECD commissioned reviews and independent external investigations by the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office and the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee. However, DEECD has been slow to respond to the findings of these reports and has done little to address them.

As part of its public private partnership procurement model, DEECD has developed a framework that requires these schools to adopt a long-term approach to asset maintenance, and provides suitable accountability requirements to make sure this happens.

Applying the planning and accountability components of this model to all 1 537 government schools would provide far more robust and informed asset management than is presently occurring.

Findings

Current condition of school buildings

The majority of school buildings are in a functional condition. A 2012 assessment of the condition of all schools found that 67 per cent of all buildings are in good or excellent condition, requiring only routine maintenance.

However, notable issues with the school building portfolio remain and 7.5 per cent of buildings—2 042 in total, across 505 schools—are at the point of imminent failure, or have already failed. A further 3 074 buildings are below the standard DEECD requires for all school buildings. DEECD estimates that $420 million in investment is required to bring these buildings up to an acceptable standard.

In addition, 38 per cent of buildings are surplus to requirements—based on current enrolment levels—and DEECD estimates that one-quarter of all schools are out-dated, and not suitable to deliver a modern curriculum.

Investment in maintaining schools

Residual issues with the condition of buildings are influenced by a long legacy of government under-investment in the maintenance of school buildings. Industry benchmarks show that an annual maintenance investment of 2 per cent of the asset value is necessary to preserve buildings at a suitable standard.

In 2012, DEECD provided $87.1 million to schools to maintain buildings—only 32 per cent of the recommended investment level.

In the context of this underfunding, schools have adopted a reactive approach to asset maintenance, only addressing urgent issues as they occur and deferring non‑urgent and preventative maintenance works. This is likely to compound defects, leading to a need for more costly maintenance interventions in the future.

Compounding the issue of under-investment in maintenance is a lack of effective accountability of schools for maintenance funding.

Within DEECD’s devolved model of school governance, school principals have discretion over how to spend this funding, and DEECD does not check whether they spend it on maintaining buildings.

DEECD has not yet adopted a long-term approach to maintaining school buildings, nor does it require schools to plan the management of buildings over the long term.

This is an important element of better practice asset management and provides assurance that the maximum possible benefit can be derived from the considerable public investment directed towards school buildings.

Implementation of VSP and BER

Neither VSP nor BER have been fully implemented. As at February 2013, a small number of building works committed to under these programs remain underway.

While 30 per cent of VSP projects and 14 per cent of BER projects are more than six months late, these delays do not appear to have had a major impact on project costs. DEECD expects that once complete, VSP will be delivered within 1 per cent of budget, and BER within 2.8 per cent of budget.

Despite this positive result, some schools have expressed concerns about the quality of construction of BER buildings potentially leading to high maintenance costs in the future.

Program evaluation and review

While VSP and BER saw an unprecedented level of investment in Victorian Government schools, DEECD has not comprehensively evaluated these programs to determine whether they were efficiently and effectively implemented.

Opportunities to learn from these programs are likely to be lost without a more thorough post-implementation review.

Recommendations

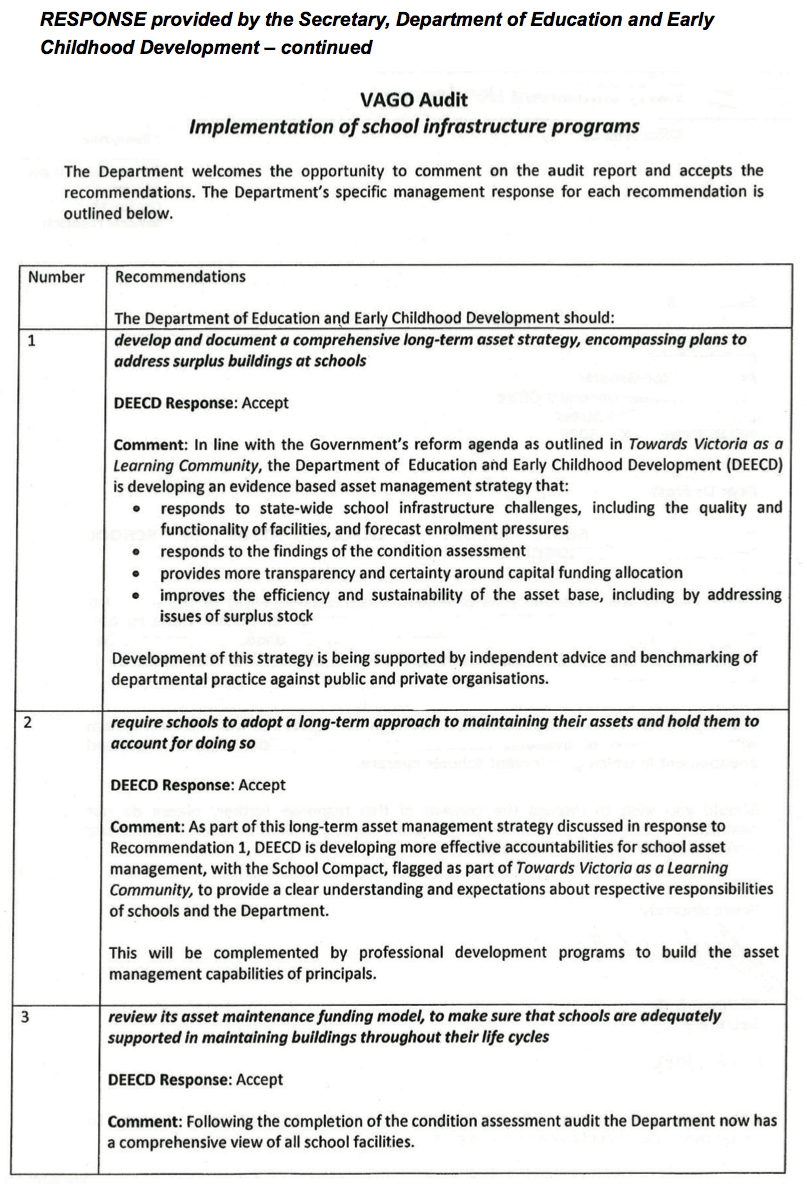

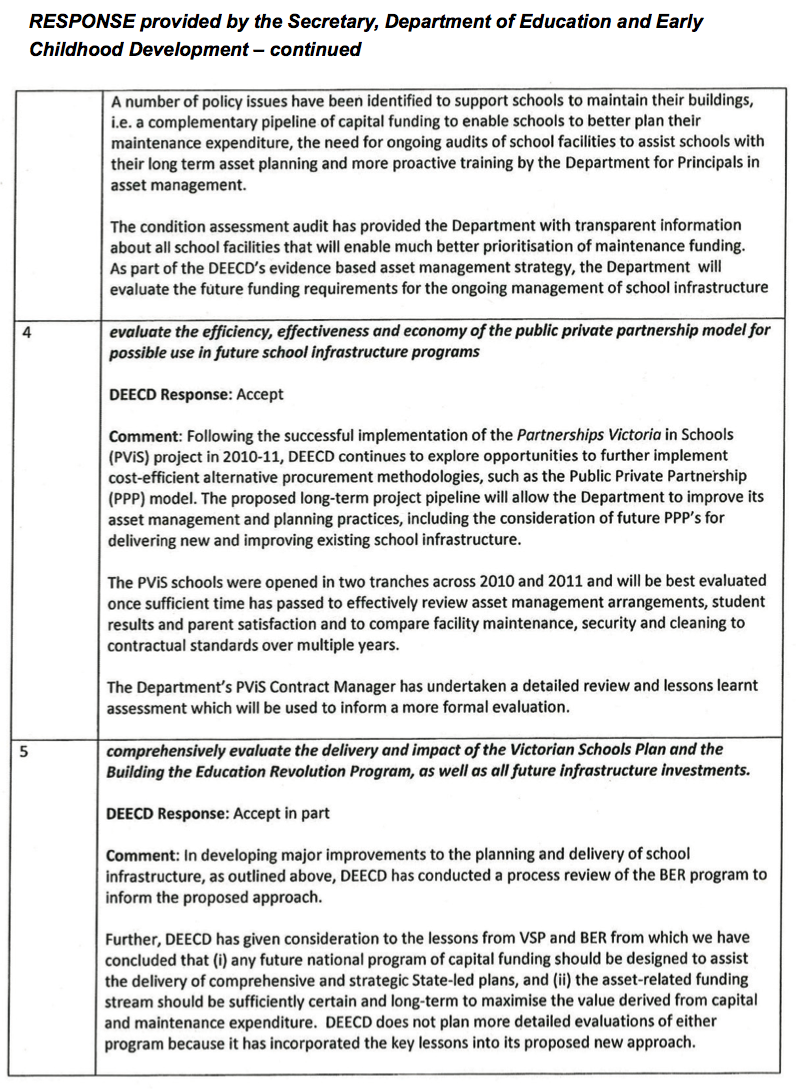

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop and document a comprehensive long-term asset strategy, encompassing plans to address surplus buildings at schools

- require schools to adopt a long-term approach to maintaining their assets and hold them to account for doing so

- review its asset maintenance funding model to make sure that schools are adequately supported in maintaining buildings throughout their life cycles

- evaluate the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of the public private partnership model for possible use in future school infrastructure programs

- comprehensively evaluate the delivery and impact of the Victorian Schools Plan and the Building the Education Revolution program, as well as all future infrastructure investments.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Improving educational outcomes for school students has been a long-term policy priority of several successive state governments. It is the principal goal of the current government’s vision for school education reform, Toward Victoria as a Learning Community.

International research indicates that the physical environment in which people learn enhances learning outcomes if:

- students are learning in new or upgraded facilities

- there is suitable thermal comfort, acoustics and natural light

- facility design supports effective teaching, learning and the delivery of a modern curriculum.

Research also suggests that improved outcomes are sustained if quality is preserved through effective maintenance programs.

1.2 Victorian Government school infrastructure

The Victorian Government school infrastructure portfolio consists of 1 537 schools with a combined asset and land value of $13.9 billion. School buildings make up almost 96 per cent of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s (DEECD) building portfolio.

There are five types of schools within the portfolio as set out in Figure 1A. Primary schools account for 74 per cent of the total.

Figure 1A

Government schools in Victoria

School type |

Number |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

Primary |

1 137 |

74 |

Primary/Secondary |

75 |

5 |

Secondary |

245 |

16 |

Special |

76 |

5 |

Language |

4 |

>1 |

Total |

1 537 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

In 2012, 546 435 students, or 63.4 per cent of all Victorian school students, attended a government school.

1.2.1 Roles and responsibilities

DEECD is responsible for the strategic management of the Victorian Government school building portfolio. This includes planning for, and providing advice to government regarding investment in new schools.

Day to day management of infrastructure is the responsibility of school principals and is therefore spread across all schools within the portfolio. Schools are required to maintain buildings at an appropriate standard, so they are safe, secure and comply with relevant regulations.

A proportion of the annual funding DEECD provides to schools is notionally allocated for the maintenance of buildings. However, Victorian Government schools operate within a devolved model which gives principals and school communities the power to make decisions that best reflect their local needs.

In keeping with this principle of local autonomy, schools have discretion to direct maintenance funding as they choose.

1.3 Recent investment in school infrastructure

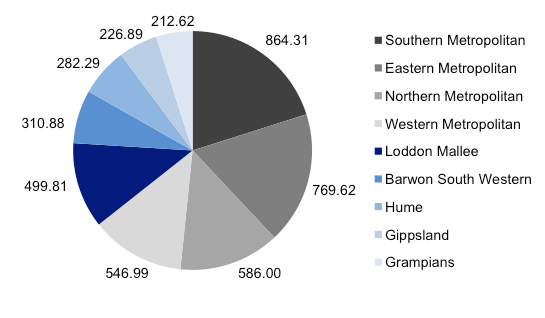

Between 2007 and 2012 Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Building the Education Revolution (BER) program invested $4.5 billion in Victorian Government school infrastructure. Figure 1B shows the distribution of VSP and BER investment.

Figure 1B

VSP and BER investment by region, $ million

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.3.1 The Victorian Schools Plan

In 2007, the Victorian Government announced a major increase in infrastructure investment under VSP, which was a policy commitment to rebuild or modernise every Victorian Government school by 2017.

This announcement was accompanied by an initial investment of $1.93 billion between 2007 and 2011—an average of $483 million each year—which more than doubled the average annual expenditure on school infrastructure from the preceding seven years. During this time, 553 schools across Victoria underwent capital works as part of VSP.

VSP consisted of several components, including programs which saw new schools built in growth corridors, the replacement of small rural schools and upgrades to existing buildings at schools across the state. VSP also incorporated a significant and complex program of ‘regeneration’ projects, which involved multiple schools in vulnerable communities combining and working together to develop new approaches to teaching and learning, underpinned by new modern infrastructure.

However, following the change of government in 2011, the VSP commitment to rebuild or modernise all government schools by 2017 has not been pursued. Therefore, all references to the VSP throughout this report refer to the 553 schools that received capital works as part of the VSP between 2007 and 2011.

VSP was underpinned by a policy framework called Building Futures which sought to place the achievement of learning outcomes at the centre of decision-making about infrastructure investment.

The Building Futures framework saw all potential projects move through a staged development process as follows:

- stage 1—project identification

- stage 2—educational rationale

- stage 3—feasibility study

- stage 4—prioritisation and approval

- stage 5—implementation

- stage 6—evaluation.

1.3.2 Building the Education Revolution

In 2009, the Commonwealth Government announced $16.2 billion towards government school infrastructure under BER, a nationwide economic stimulus plan intended to mitigate the impact of the global financial crisis. The Commonwealth BER funding covered capital works only, and did not include a component for ongoing operation or maintenance.

Through this program, the Victorian Government received $2.545 billion to invest in Victorian Government school infrastructure through three streams:

- Primary Schools for the 21st Century—$2 203 million

- Science and Language Centres for the 21st Century—$137 million

- National School Pride—$205 million.

Through BER, 86 per cent of all Victorian Government schools underwent capital works between 2009 and 2012.

1.4 Principles of better practice asset management

The Department of Treasury and Finance supports government departments to manage public assets through the provision of better practice guidance.

This guidance highlights that effective asset management includes maximising the service potential of assets so that they are appropriately used and maintained. It also emphasises achieving value for money by taking into account the full life cycle costs of assets.

The key principles set out in this guidance include:

- focusing on service delivery—asset practices and decisions should be guided by service delivery needs

- following an integrated approach—asset planning and management should be aligned with intended service outcomes, overarching plans and policies

- evidence-based decision-making—rigorous information about the costs, benefits, risks and alternatives of asset investments should underpin decision‑making.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to assess whether DEECD is managing school infrastructure efficiently and effectively. It looked at whether:

- major school infrastructure programs—VSP and BER—have achieved their intended objectives

- lessons learnt from these programs and reviews have informed improvements to asset management practices

- current asset management practices, including planning for infrastructure needs in growth areas, are adequate.

The audit reviewed VSP and BER to determine the effectiveness of these programs. It examined processes at DEECD’s central office, regional offices and a sample of eight schools to assess how lessons learnt through these programs are informing DEECD’s current approach to managing school infrastructure.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994, and was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Total cost of the audit was $370 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

Part 2 of this report assesses the impact of VSP and BER on the condition of government school buildings. Part 3 examines how DEECD is managing asset challenges and Part 4 looks at the implementation of VSP and BER.

2 Current state of government school buildings

At a glance

Background

A total of $4.5 billion has been invested in government schools through the Victorian Schools Plan and the Building the Education Revolution program. As a result, the asset value of the 1 537 government schools has increased by 27 per cent to $13.9 billion.

Conclusion

Sixty-seven per cent of Victorian Government school buildings are in satisfactory operational condition. However, 7.5 per cent of buildings require urgent works to remain safe and useable. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) anticipates that $420 million is needed to bring all schools up to the standard it requires.

Findings

- DEECD's recent assessment of the condition of school buildings provides a timely account of the state of school assets.

- Thirty-three per cent of schools—505 in total—have buildings that are at the point of failure or have already failed.

- The amount of excess space in schools has increased from 15 per cent, before VSP and BER, to 38 per cent in 2012.

2.1 Introduction

Prior to the Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Building the Education Revolution (BER) program, the government school portfolio consisted of 1 597 schools with a combined land and building value of $10.7 billion.

The portfolio was facing several challenges which were compromising schools' ability to achieve desired learning outcomes:

- Two-thirds of Victorian Government schools were more than 20 years old and therefore could not provide a modern learning environment for students.

- An estimated $230 million was required to address the backlog of maintenance across schools.

- Some 67 per cent of all primary schools had fewer than 300 students enrolled, creating resourcing pressures and challenging schools' abilities to deliver a diverse curriculum.

- Approximately 15 per cent of school buildings were excess space, and were not required, based on enrolment levels.

These issues prompted the Victorian Government to undertake significant capital works through VSP in order to modernise the school infrastructure portfolio. BER, announced in 2009, was implemented concurrently with VSP.

As a result of VSP and BER, the value of the portfolio has increased by 27 per cent to $13.9 billion and through mergers and consolidations, there are now fewer schools—1 537 in total.

This Part of the report assesses the impact of these programs by reviewing the current condition of school buildings.

2.2 Conclusion

The majority of Victorian school buildings are currently in operational condition and require only routine maintenance to be kept in this condition.

However, despite the $4.5 billion invested in school buildings over the past five years, a further $420 million in capital investment is needed to bring all school buildings up to the standard the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) requires.

VSP and BER investments have also contributed to a rapid rise in excess school space which will now require additional maintenance funding to remain in good condition.

2.3 Current condition of school buildings

In the first half of 2012, DEECD assessed the condition of all Victorian Government school buildings, following the VSP and BER investment of $4.5 billion.

DEECD assessed the condition of each element within each building of each school campus in Victoria. It rated building condition on a five point scale, from poor to excellent, with each point along the scale being associated with remedial action: from capital replacement, for buildings at the poorest end of the scale, to routine maintenance, for those at the highest end.

2.3.1 Condition assessment results

The condition assessment found that the majority of school buildings (66.9 per cent) were in 'excellent' or 'good' condition, meaning they showed only superficial signs of wear and tear and can be preserved with routine maintenance.

However, a minority of buildings (7.5 per cent or 2 042 individual buildings across 505 schools) are in the lowest two categories—at the point of failure, or having already failed. Figure 2A summarises the results across the full portfolio.

Figure 2A

Condition audit results

|

Condition |

Description |

Action required |

School buildings assessed in this condition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Excellent |

Either new or recently maintained—no signs of deterioration. |

Can be repaired with routine maintenance. |

5.5 |

|

Good |

There is superficial wear and tear—minor defects or minor signs of deterioration. |

Can be repaired with routine maintenance. |

61.4 |

|

Fair |

Substantial components require repair. |

Some work can be completed through routine maintenance; some supplementary funding may be required. |

25.6 |

|

Worn |

Substantial components have deteriorated badly—a risk of imminent failure. |

Supplementary funding or capital replacement required. |

6.9 |

|

Poor |

Component has failed—is not operational or has deteriorated to an extent that requires replacement. |

Capital replacement required. |

0.6 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

The data showing that two thirds of the school building portfolio is currently in good operational condition is positive, but expected, given the scale of recent infrastructure investment under VSP and BER.

Nevertheless, keeping school buildings in this condition will require sustained investment in maintenance over the life cycle of these buildings. DEECD's history of underfunding maintenance and the implication this raises for schools over the long term is discussed in Part 3.

Despite the majority of school buildings being in good operational condition, these results also show that one-third of schools have one or more buildings that have failed, or are at the point of failure.

DEECD has estimated that a further $420 million is needed to return these buildings to an operational standard. Notably, almost a quarter of this expenditure is required in the Eastern Metropolitan region, despite schools in this region receiving $770 million of investment under VSP and BER.

Barwon South West has the greatest investment requirements when total investment is set against the number of schools in the region—with an average investment requirement of $725 076 per school. This is almost double any other region.

Figure 2B

Investment required across regions to bring schools to operational standard

|

Region |

Number of schools |

Amount to reach threshold ($ million) |

Average investment required per school ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Barwon South Western |

129 |

93.5 |

725 |

|

Eastern Metropolitan |

241 |

104.6 |

434 |

|

Western Metropolitan |

142 |

44.9 |

316 |

|

Northern Metropolitan |

187 |

56.9 |

304 |

|

Loddon Mallee |

156 |

38.3 |

246 |

|

Hume |

156 |

30.8 |

197 |

|

Grampians |

128 |

18.3 |

143 |

|

Gippsland |

150 |

13.5 |

90 |

|

Southern Metropolitan |

248 |

17.5 |

71 |

|

Total |

1 537 |

418.3 |

272 |

Note: Differences due to rounding.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

Figure 2B clearly shows that despite the $4.5 billion invested in school buildings over the past five years considerable further investment is needed to bring all school buildings up to the standard DEECD requires.

Functionality of the school building portfolio

A key driver of VSP was the need to modernise Victorian Government schools to create learning spaces capable of supporting contemporary learning technologies. In 2010, DEECD analysed the functionality of its school buildings. This resulted in it classifying a quarter of its buildings as outdated, and not suited to delivering a modern curriculum.

While VSP and BER will have had some impact on this, the 2012 condition assessment did not assess the buildings' ability to support the delivery of a modern curriculum. It is therefore unclear the extent to which these programs have addressed the problem of functionality, and how many schools continue to be unsuitable for the delivery of a modern curriculum. This matter is further discussed in Part 4.

2.3.2 Excess space

Based on the number of students enrolled in Victorian Government schools, the school building portfolio is currently 38 per cent surplus to requirements.

Prior to VSP and BER, the level of excess space was approximately 15 per cent, indicating that these programs have more than doubled the amount of surplus space in Victorian Government schools.

The excess space is a mix of teaching and non-teaching space, including corridors and administration space. Similar to overall excess space, excess teaching space has increased from around 8 per cent prior, to VSP and BER, to 25 per cent currently.

One objective of VSP was to consolidate school buildings in order to address inefficiencies associated with surplus space. Though VSP sought to take steps to address this, BER's commitment to create new buildings at all primary schools effectively augmented, rather than consolidated, the portfolio.

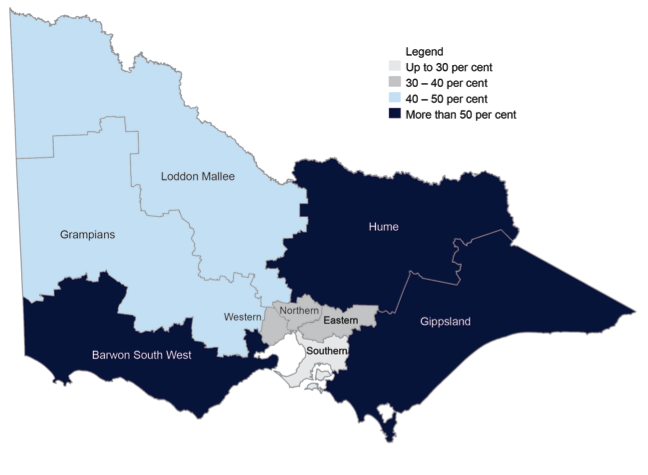

The scale of oversupply of school buildings varies across regions, with Barwon South Western region having the greatest oversupply, at 55 per cent, and Southern Metropolitan the least, at 29 per cent.

There is also more excess space in regional Victoria than in metropolitan Victoria. Figure 2C illustrates the distribution of excess space.

Figure 2C

Excess space in Victorian Government schools across regions

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

2.3.3 Implications of the current condition of school buildings

With the majority of school buildings currently in good operational condition, DEECD and schools are well placed to capitalise on the recent investment by working to maintain building functionality over the long term. Doing so will require prudent asset management practices, including:

- a long-term asset strategy incorporating life cycle planning for the full school building portfolio

- long-term plans for the operation and maintenance of buildings, at the school level

- sustained investment in the maintenance of school buildings.

The next Part discusses DEECD's current practices, and their ability to meet challenges associated with asset management over the long term.

3 Meeting asset management challenges

At a glance

Background

Effective asset management requires long-term planning, underpinned by a clear understanding of service needs and of the condition of assets. Ongoing maintenance of assets is critical to keeping them in a functional condition over their life cycles, and to making the most of public investment.

Conclusion

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) is not managing school infrastructure efficiently and cost-effectively. Historical underfunding of maintenance, a lack of life cycle planning and a lack of accountability for schools’ expenditure of maintenance funds, are compromising the effective management of school buildings. DEECD is aware of the need to enhance asset management practices, but has not yet taken effective action.

Findings

- DEECD does not plan assets over their life cycles.

- Schools receive less than a third of the funding they require to maintain buildings according to industry standards, and are not effectively held to account for their expenditure of maintenance funding.

- $420 million is required to bring the portfolio to the standard DEECD requires.

- DEECD’s prioritisation of capital investment lacks transparency and has been made without reference to comprehensive data on the condition of assets.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop and document a comprehensive long-term asset strategy, encompassing plans to address surplus buildings at schools

- require schools to adopt a long-term approach to maintaining their assets and hold them to account for doing so

- review its asset maintenance funding model to make sure that schools are adequately supported to maintain buildings over their life cycles

- evaluate the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of the public private partnership model for possible use in future school infrastructure programs.

3.1 Introduction

The school infrastructure portfolio consists of more than 27 000 buildings across 1 537 schools.

Under the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s (DEECD) devolved model of school administration, principals are responsible for the day to day management of school buildings, including the ongoing maintenance of these buildings.

DEECD is responsible for strategic management of the portfolio as a whole.

3.2 Conclusion

DEECD cannot demonstrate that it has managed school infrastructure assets efficiently and cost-effectively. It has not developed a long-term approach to managing school infrastructure and has failed to hold schools to account for using their maintenance funds appropriately. Currently, $420 million is required to bring the portfolio up to the standard DEECD requires.

While the Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and Building the Education Revolution (BER) investments have had a positive impact on the condition of many schools, an historical legacy of underfunding schools to maintain their buildings has led to the degradation of some school assets to the point of failure.

Despite the widely accepted position that careful long-term planning and a sustained program of maintenance over time is central to effective asset management, DEECD does not require schools to adopt this approach. DEECD has received advice over a number of years to adopt a long-term approach to managing school assets, but has not yet done so.

One key exception is the 12 schools built through a public private partnership (PPP) model between 2009 and 2011. While DEECD requires the contracted private sector operator of these schools to plan for and maintain facilities over the long term, the remaining 1 525 government schools in Victoria have no such obligation.

Until 2012, DEECD did not have a comprehensive understanding of the condition of school buildings, and therefore could not adequately prioritise investment in repairing and rebuilding schools.

Recognising this deficiency, DEECD has recently assessed the condition of all schools to inform future capital investment decisions. However, more work is necessary to bring DEECD’s asset management practices in line with industry standards.

3.3 Maintaining school buildings

3.3.1 Legacy of maintenance underfunding

DEECD has consistently underfunded schools to maintain their buildings, leading to the current situation of 2 042 buildings across 505 schools being at the point of failure, or having already failed. In addition $420 million is required to bring all school buildings up to a functional standard.

Industry standards for asset management recommend annual investment of approximately 2 per cent of the asset value to suitably maintain buildings. Given the current school buildings’ total replacement value of $13.6 billion, an annual investment of approximately $272 million would be necessary to adequately maintain school buildings according to these benchmarks.

In 2012, DEECD provided $87.1 million to schools to maintain buildings. This is only 32 per cent of the recommended investment levels. This low level of maintenance funding is a key contributor to the current backlog of urgently required maintenance works at Victorian Government schools.

Figure 3A

School maintenance funding, 2012

School type |

Total replacement value ($ billion) |

Benchmark annual maintenance funding ($ million) |

Actual annual maintenance funding ($ million) |

Actual

as a percentage of benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Primary |

$6.6 |

$132.0 |

$25.4 |

19 |

Primary/ Secondary |

$1.2 |

$24.0 |

$4.8 |

20 |

Secondary |

$5.2 |

$104.0 |

$20.3 |

19 |

Other |

$0.6 |

$12.0 |

$2.6 |

21 |

Discretionary funding |

|

|

$25.0 |

|

BER related maintenance funding |

|

|

$9.0 |

|

Total |

$13.6 |

$272.0 |

$87.1 |

32 |

Note: Annual maintenance funding incorporates funding provided through the Student Resource Package and supplementary maintenance funding.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development provides additional maintenance funding for emergency situations which is distributed on an as-needed basis at its discretion.

In 2012, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development also provided funding to schools to fund maintenance works related to Building the Education Revolution building activity.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Audited schools advised that in the context of current funding levels, they elected to focus on urgent maintenance works only and typically deferred minor works until they became urgent.

Principals saw this as a practical necessity in the context of insufficient funding. However, this practice has significant consequences both for individual schools and DEECD’s broader strategic asset management practices. Avoiding preventative maintenance, and not addressing minor maintenance issues as they occur, can exacerbate small issues that lead to more significant degradation, requiring more costly interventions.

DEECD’s method of calculating maintenance funding for individual schools uses the number of students as the major determinant of funding levels. The number and size of school buildings and their condition are subordinate considerations. This means that in situations where schools have significant excess space, they receive less maintenance funding than they would have if they were operating closer to capacity.

Over-entitlement has rapidly increased in recent years, leading to the current situation where there is an over-entitlement of 38 per cent across all government schools. This means that many schools are now in a position where new buildings created through VSP or BER are receiving no additional maintenance funding.

While this has immediate implications for the management of these schools, it also presents a very significant risk to DEECD that these new buildings will not be well maintained and that the full benefits of these investments will not be realised over time.

3.3.2 Accountability structures

Compounding the lack of sufficient funding to address maintenance issues is a lack of effective accountability for how schools spend maintenance funding. While DEECD provides schools with a notional allocation of maintenance funding, it does not hold them to account for how they use it. DEECD therefore has no assurance that these funds are being appropriately spent on maintaining buildings.

The exception to this is when schools apply to DEECD for supplementary maintenance funding to address urgent maintenance issues. In these circumstances, DEECD reviews schools’ maintenance activities to confirm they have been spending allocations appropriately before providing supplementary funding.

Given that on average 8 per cent, or 127 schools, have received supplementary maintenance funding each year over the past three years, this reactive approach to assessing school maintenance practices does not constitute effective accountability across the portfolio.

These accountability structures are reflective of the Victorian Government’s devolved school governance model, which gives principals autonomy to make decisions about the operation of their own schools, in collaboration with their school communities. While DEECD’s approach is consistent with this governance model, it is nevertheless a significant impediment to its strategic management of the asset portfolio, and to managing assets effectively over their life cycles. DEECD advised that it recognises the need for enhanced accountability structures and has indicated that it is working to improve this.

A lack of accountability can create incentives for schools to deliberately under-invest in building maintenance, allowing buildings to degrade to a point where they will require a full rebuild rather than simple repair. While all schools visited during the audit advised that they spend more on building maintenance than DEECD allocates each year, DEECD’s lack of accountability over expenditure means it has no way of knowing that this is the case.

The increasing and significant burden of urgent maintenance requirements indicates that DEECD’s current approach to overseeing schools’ maintenance of buildings and expenditure of maintenance funding, is not working.

3.3.3 Responding to advice

Since 2008, DEECD has received the following advice from multiple sources, including VAGO and consultants it has commissioned:

- that funding levels are insufficient to support effective life cycle maintenance of the school building portfolio

- that accountability structures are ineffective

- that there is a need for long-term planning for asset management.

However, it has not taken effective action to address these issues.

In 2008, DEECD commissioned a study of different approaches to maintaining school buildings. The report highlighted that full life cycle maintenance would require investment of 2.5 per cent of the value of the asset portfolio.

As a result of this work, DEECD piloted three maintenance models to explore their potential for the wider school building portfolio:

- Facility maintenance managers—employed to work with groups of schools to manage, organise and monitor maintenance activities.

- Trade panels—establishing panels of pre-approved suppliers across five trades to work with a group of 70 schools.

- Partnerships Victoria in Schools—piloting a full life cycle approach to maintenance by monitoring the implementation of this approach at PPP schools.

DEECD engaged consultants to undertake a preliminary review of the pilot programs in 2011, finding that all three:

- appear to deliver quality maintenance outcomes that represent good value for money

- provide time savings for principals

- require a robust reporting and evaluation framework to capture their benefits and costs over time.

However, DEECD has been slow to respond to these findings and has not implemented any changes to its maintenance program as a result of these pilot studies.

Underfunding of maintenance, and its impact on asset condition, was also highlighted in VAGO’s 2008 performance audit School Buildings: Planning, Maintenance and Renewal and later in the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee’s (PAEC) 2010 follow-up review of this audit.

DEECD advised government of the need to increase funding for ongoing maintenance in 2009 and 2011, however, this was only in the context of the increase to the asset base as a result of BER.

DEECD commissioned further work on better practice asset management in 2012 highlighting the importance of this issue, as well as the importance of life cycle planning of assets, to support their sustainability and cost-efficient operation over the long term. The need for long‑term planning was also highlighted by VAGO in 2008. DEECD has not yet adopted a long-term approach to asset management.

DEECD’s lack of action in response to these reports has directly contributed to the need for a $420 million investment to get all schools to the standard it requires.

Broader factors such as the ageing of assets and increase in the total asset base as a result of VSP and BER have also contributed to the need for this investment. However, it is the underlying issues with DEECD’s asset management practices which, though highlighted numerous times, remained unaddressed through VSP and BER, that are the key contributors to this situation.

3.4 Effective asset management

3.4.1 DEECD’s approach to asset management

Better practice asset management, as set out in the Department of Treasury and Finance’s (DTF) whole-of-government guidelines, requires long-term planning, linked to strategic objectives and a whole-of-life cycle approach. It also requires decisions to be based on comprehensive information about the asset portfolio, and for asset management to be guided by service needs.

While DEECD’s asset management approach aligns with DTF’s guidelines, critical gaps have impeded the extent to which it can manage the school building portfolio effectively.

Specifically, DEECD has not managed assets within the context of a comprehensive long-term strategy that explicitly and transparently sets out how it will manage school buildings through all stages of the asset management cycle. In the absence of such a strategy, DEECD cannot be sure that it is managing assets in the most efficient manner over the long term.

Data on the condition of school buildings

DEECD did not have a comprehensive understanding of the condition of all school buildings until 2012, when it undertook a whole-of-portfolio assessment of the condition of school buildings. This was the first such review since 2005. Between 2008 and 2011, rolling audits were undertaken of a small proportion of schools. A quarter of schools were assessed during this period.

This has meant that during this period, capital investment decisions were made on the basis of incomplete data, and there is no certainty that the most urgent needs were being prioritised.

3.4.2 Prioritising capital investment

DEECD’s processes for prioritising capital investment include consulting with regional offices and applying criteria related to the school enrolment and building condition. However, investment does not occur within the context of a clear policy framework and, therefore, priorities have varied over recent years. This has resulted in a lack of transparency for schools around funding decisions, and for those schools that have persistent buildings issues, considerable frustration over the lack of clarity around the process for accessing funding for capital works.

DEECD is currently in the process of developing a comprehensive asset management strategy, which it anticipates will be completed by mid-2013. DEECD advises that the purpose of this work is to build a strong case to put to government regarding the need for a project pipeline underpinned by a funding commitment.

Work commissioned recently to examine international better practice in asset management, as well as the 2012 whole-of-portfolio condition assessment, will be key inputs in to the strategy, and will constitute a solid evidence base for DEECD to leverage off.

Completing and implementing a robust long-term asset management strategy is overdue and is critical to DEECD effectively managing school buildings.

Building Futures policy framework

Under VSP, capital investment decisions were underpinned by the Building Futures policy. This policy required schools to demonstrate a need for capital investment and was informed by both the condition of buildings and the education outcomes that capital investment could achieve.

While it created a consistent framework through which investment decisions were made, not all schools were invited to participate in the Building Futures process and there was a lack of transparency around how schools were selected to become involved.

VAGO’s 2008 audit highlighted this issue, noting that there was no clear documentary trail explaining the basis for selecting schools to be included in VSP. The report recommended that DEECD document and apply robust processes to assess the building needs of schools, and to use this to inform selection of schools to participate in building programs.

This issue was revisited by PAEC in 2010, which recommended that DEECD publicly disclose the process and rationale for schools’ selection in building programs.

DEECD has not taken action in response to these recommendations, and its processes for prioritising capital investment continue to lack transparency. The Building Futures framework has not been applied to any new projects since 2011.

Current capital improvement program

Over the past two years, investment has been directed towards projects identified as election commitments, and a small number of additional projects that DEECD had identified as high priority, which had been through various stages of the Building Futures process prior to 2011.

DEECD applies consistent criteria to identify investment priorities, including the condition of assets and enrolment pressures. However, the lack of an overarching policy framework driving investment means that DEECD cannot be sure and cannot demonstrate that it is:

- appropriately channelling investment in terms of long-term strategic management of the asset portfolio

- prioritising investment in a manner that is transparent to schools.

DEECD’s up-to-date, comprehensive data about its asset portfolio should allow it to engage in better longer-term asset life cycle planning.

Investing in new schools

Timely supply of new schools in growth areas is a critical issue for DEECD. While DEECD has sound processes to identify the need for new schools, delivery lags behind demand.

DEECD works with the Growth Areas Authority to develop Precinct Structure Plans which identify and document the public infrastructure needs of Victoria’s growth communities. Through this process, DEECD has identified a need for 83 schools in growth communities to be delivered at a rate of five or six per year.

Despite advice to government on the urgent need for schools in growth communities, DEECD has only been successful in securing funding for five new schools over the past two years.

The lack of timely supply of schools in growth areas creates pressure on existing infrastructure, which can lead to the accelerated deterioration of assets. While portable classrooms can provide an interim solution, schools have expressed concern about their use over the longer term, given their tendency to infringe on open space and their design limitations.

3.4.3 Asset management under the public private partnership model

Between 2009 and 2011, 12 new schools were built in Victoria’s growth areas using a PPP procurement model. This model is intended to provide value for money in both the construction and operation of assets, by transferring maintenance obligations and whole-of-life cycle asset risks to the private sector. It also creates incentives for quality construction and effective preventative maintenance over the long term.

For these 12 schools, DEECD enforces a longer-term approach to maintaining assets, contractually requiring operators to develop and implement:

- asset management plans, which include a program of planned preventative maintenance

- five-year work plans, which cover the nature, scope, timing and cost of planned maintenance

- annual work plans, consistent with the five-year plans

- monthly maintenance schedules, consistent with the annual works plan and incorporating reporting on actual maintenance performed.

These requirements reflect better practice in asset management, and demonstrate that DEECD understands the necessary approach to support the long-term functionality of school buildings.

While this approach will drive effective long-term maintenance of the 12 schools built through PPPs to date, the remaining 1 525 schools in the broader portfolio have no such obligations. If DEECD continues not to require schools to plan for and implement preventative maintenance over their buildings’ life cycles, the renewed asset base will deteriorate, significantly compromising the potential benefits of this major public investment.

DEECD advised that it is seeking to increase the number of PPP schools in Victoria, but is yet to undertake a thorough review or evaluation of the PPP model. Reviewing the effectiveness of this model and any lessons for future projects should be seen as a priority. DEECD advises that work has recently commenced on this.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop and document a comprehensive long-term asset strategy, encompassing plans to address surplus buildings at schools

- require schools to adopt a long-term approach to maintaining their assets and hold them to account for doing so

- review its asset maintenance funding model to make sure that schools are adequately supported in maintaining buildings throughout their life cycles

- evaluate the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of the public private partnership model for possible use in future school infrastructure programs.

4 Implementation of recent infrastructure programs

At a glance

Background

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) implemented two major school infrastructure programs between 2007 and 2012—the Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Commonwealth’s Building the Education Revolution (BER) program.

Conclusion

DEECD has not evaluated how efficiently and effectively it implemented these programs, nor whether they have achieved their expected objectives. As a result, it has neither effectively identified issues and improvement opportunities, nor determined the impact of this $4.5 billion investment.

Neither program was completed by December 2012. DEECD expects that once complete, VSP will have been delivered within 1 per cent of its original budget, and BER within 2.8 per cent of its original budget.

Findings

- DEECD has not evaluated whether VSP achieved its expected objectives, and whether it is having a desired impact on learning outcomes.

- Almost a third of VSP projects are expected to run six months late, and 26individual projects are expect to finish more than a year late.

- Although it was expected to finish in 2011, 42 BER projects are still underway.

- DEECD has undertaken limited evaluation of BER to identify opportunities to improve capital works procedures.

- While BER is expected to be completed within 2.8 per cent of its original budget, some schools expressed concerns about the quality of construction.

Recommendation

DEECD should comprehensively evaluate the delivery and impact of VSP and BER, as well as all future infrastructure investments.

4.1 Introduction

The Victorian Schools Plan (VSP) and the Commonwealth Government’s Building the Education Revolution (BER) program saw significant investment in the renewal and upgrading of Victorian Government school infrastructure between 2007 and 2012.

Under VSP, $1.93 billion was committed to rebuild, modernise or develop 553 schools between 2007 and 2011. The objectives of VSP were to:

- provide school infrastructure that enables optimal student outcomes

- rationalise the asset portfolio

- increase school and community partnerships.

In 2009, the Commonwealth Government committed to investing $2.545 billion in Victorian Government schools under BER as part of its broader program of economic stimulus activities, designed to mitigate the impact of the global financial crisis. The objectives of BER were to:

- provide economic stimulus through the rapid construction and refurbishment of school infrastructure

- build learning environments to help children, families and communities participate in activities that will support achievement, develop learning potential and bring communities together.

4.2 Conclusion

Recent infrastructure programs saw an unprecedented level of building activity take place within government schools in a relatively short period of time. Despite their significance, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has not comprehensively evaluated these programs to determine their effectiveness, or how efficiently they were implemented.

Widespread activity on the scale of VSP and BER offers considerable opportunities to enhance the efficiency of future infrastructure programs by reviewing their implementation, capturing the lessons learned, and making associated improvements.

However, because DEECD has not comprehensively or promptly evaluated these programs, it has missed a valuable opportunity to make improvements to its capital works processes. Although DEECD has recently commenced evaluating these programs, there is a risk that important lessons will have been lost because it has not occurred in a timely way.

As at December 2012, neither VSP nor BER programs had been fully implemented. Despite some considerable time delays for some projects, DEECD expects that they will be delivered, respectively, within 1 per cent and 2.8 per cent of their initial budgets, when fully implemented.

4.3 Evaluation of VSP and BER

4.3.1 Availability of information about the delivery of VSP and BER

DEECD does not maintain comprehensive data on the timely and cost-effective delivery of VSP or BER. This is mainly due to DEECD contracting out VSP and BER project management responsibilities to an external firm.

DEECD is provided with regular reports on the delivery of these projects to facilitate ongoing monitoring during implementation. However, it has yet to comprehensively review the whole program to identify the extent to which it has been delivered efficiently and effectively, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

While the BER objectives were set by the Commonwealth, making program achievements more relevant to that level of government, VSP was entirely state government funded. It is therefore critical that the outcomes of VSP investment are understood in relation to its objectives, however, DEECD has completed no evaluations of this kind.

More broadly, DEECD does not have systems to understand how the new learning environments created through VSP are impacting on student outcomes, nor does it monitor school/community partnerships to determine whether these are increasing.

While the increase in excess space, discussed in Part 3, indicates that the VSP objective of rationalising the asset portfolio has not been achieved, this is largely a consequence of the concurrent delivery of extra BER facilities.

A lack of evaluation and monitoring means that DEECD cannot demonstrate the effectiveness of VSP’s $1.93 billion investment. Understanding outcomes of specific programs is critical to improving the efficiency of public expenditure, and would strengthen the basis of DEECD’s bids for investment in the future.

DEECD considers that its recent assessment of the condition of all schools is an ‘objective measure’ of the impact of BER and VSP. However, given that the condition of school buildings is a product of multiple factors, including building age, schools’ ongoing maintenance activities and in some instances, investment through other sources, it is not possible to directly attribute the current condition of school buildings to VSP and BER alone.

Limited evaluation of BER

While no evaluation of VSP has taken place, some aspects of BER have been reviewed. In 2012, DEECD commissioned a review of the effectiveness of its delivery of BER to identify opportunities to improve its ongoing capital works activities. This review identified a number of issues with BER, specifically:

- a lack of school engagement

- delays in the commencement of building works

- instances of sub-standard workmanship

- a perceived lack of value for money

- instances of projects being de-scoped to meet costs.

However, the review was limited in scope and did not articulate the drivers or scale of these issues.

It made a number of recommendations intended to address the identified issues, including the greater use of template designs in future building projects, greater representation from schools in project development and delivery, and the use of external project managers for more complex projects. DEECD has yet to develop a formal response to the recommendations of this review.

DEECD has also surveyed the principals of 40 schools involved in BER to determine whether they think it will positively impact student learning outcomes at their schools. The survey found that principals were overwhelmingly positive about the likely impact of BER on teaching and learning outcomes. However, it only sought principals’ views on likely impacts. Though these views are important, they provide limited insight into the actual impact of BER.

DEECD has made some incremental improvements to its capital works processes as a result of issues identified during the implementation of these programs.

While post-occupancy evaluation of VSP and BER projects has recently commenced, the lack of timely evaluation means that current capital works projects could be replicating avoidable issues due to the time lag of the evaluations. Given that up to four years has passed since some of these projects were completed, it is likely that the current evaluations will not capture all the relevant issues. This is a lost opportunity.

4.4 Implementation of VSP

As of early 2013, $1.91 billion of the total estimated VSP investment of $1.93 billion has been spent. DEECD estimates that a further $1.8 million will be needed to complete the program as planned, or less than 1 per cent of the total estimated investment.

Some $1.333 billion (70 per cent) was allocated to 231 projects with a budget of $1 million or more. These were project managed by an external firm and DEECD was able to acquire timely, comprehensive data about these programs. Due to the absence of comprehensive data about the remaining VSP projects, the following section only focuses on these 231 projects.

4.4.1 Timely delivery of VSP projects

Sixty per cent of projects have been completed, or are expected to be completed, within three months of the original schedule. However, 30 per cent of projects ran, or are forecast to run, more than six months later than scheduled. This includes 26 projects that are expected to conclude more than a year late, three of which are expected to conclude more than two years late.

DEECD advised that delays were frequently caused by altering the scope of VSP projects to include BER works, as well as latent conditions of building sites which took time to address.

However, 29 per cent of projects also experienced delays in design and tendering, which indicates that there are opportunities for DEECD to improve its planning processes. The lack of timely post-occupancy evaluation of these projects means that the specific causes of these issues have not been captured. There is therefore no assurance that opportunities to revise processes to avoid the recurrence of these issues have been identified.

In December 2012, 24 VSP projects remained underway, with these projects running 10 months late on average.

4.4.2 On-budget delivery of VSP projects

For the 231 projects with budgets of more than $1 million, DEECD anticipates that final expenditure will be $1.8 million over budget. This is an overrun of less than 1 per cent of the total budget for these projects.

While this is a positive outcome, there is considerable variation in the extent to which individual projects were delivered within budget parameters. A total of 90 projects were delivered over budget, and while more than half of these exceeded their budgets by less than 10 per cent, there were four instances where projects exceeded their budgets by more than 100 per cent.

These four projects are responsible for more than $10 million in additional costs. However, due to savings from the 48 per cent of projects that came in under budget, the overall program is expected to exceed costs by only $1.8 million.

These variations again highlight the importance of undertaking timely evaluation of projects, to identify the causes of both overruns and savings with a view to continuously improving processes.

4.5 Implementation of BER

BER consisted of 1 323 projects across the state.

4.5.1 Timely delivery of BER projects

BER was originally intended to be completed by March 2011, however, in June 2012 42 projects remained incomplete. A total of 701 projects—53 per cent of all BER projects—were completed or are forecast to be completed later than the time lines imposed by the Commonwealth. Specifically:

- 281 projects were up to three months late

- 229 projects were up to six months late

- 191 projects—14 per cent of all BER projects—were delayed by six months or more.

DEECD advised that there were multiple causes for delays, including unanticipated site issues and revisions to project scope to better meet schools’ needs.

DEECD also notes that the most frequent cause of project delays was that the time lines imposed by the Commonwealth did not correspond with industry standards. DEECD further advised that in many instances, Commonwealth time lines were shorter than builders’ estimates.

A critical issue affecting the timely delivery of BER projects was the need to re-tender projects in order to achieve value for money. While the main intent of BER was for building industry economic stimulus, DEECD argues that in the Victorian context, the building industry situation was more robust and therefore tender responses were often higher in cost. In some instances, DEECD chose to re-tender projects in order to pursue better value for money, which caused considerable delays.

Timing delays are problematic not only from the point of view of schools that were affected by learning spaces being available later than expected, but also the potential budgetary impact.

Of the 701 projects that missed Commonwealth deadlines, most (62 per cent) were delivered on budget. The remaining 265 (38 per cent) were over budget, but by an average of only 15 per cent.

4.5.2 On-budget delivery of BER projects

The original budget for BER was $2.545 billion. By June 2012, $2.584 billion had been spent and a further $33 million committed to complete the 42 projects that remained underway. This means that once fully implemented, BER will have exceeded its original budget by $72 million, or 2.8 per cent.

Figure 4A

Building the Education Revolution budget and expenditure at 30 June 2012

|

Component |

Budget |

Expenditure to date |

Committed expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary Schools for the 21st Century |

2 203 |

2 233 |

33 |

|

Science and Language Centres for the 21st Century |

137 |

146 |

0 |

|

National School Pride |

205 |

205 |

0 |

|

Total |

2 545 |

2 584 |

33 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

As Figure 4A indicates, the Science and Language Centres for the 21st Century program experienced the most significant budget variation—7 per cent over budget—as distinct from the Primary Schools for the 21st Century program which is expected to run 2.9 per cent over budget.

DEECD advised that the key cause of budget overruns was the high tender prices that BER projects attracted due to the strength of the Victorian building industry during the delivery period. DEECD responded to these high prices by re-tendering some projects, and accepting others but seeking cost savings from other projects to allow the full program to complete within budget.

While the intent of re-tendering components of work was to seek better value for money, the flow-on effects of these delays have led to additional program administration costs. The Commonwealth provided $30 million to the state to administer BER, however, this was fully expended by June 2011. Since then, DEECD has been administering BER through its own internal budget. These costs were estimated to be $9 million in 2011–12. This is almost 30 per cent of the original budget for administration.

While BER’s relatively modest budget overrun is a positive outcome, some schools consulted during the audit have expressed concerns about the quality of buildings and in some instances, have already experienced problems with them. There is a view among the schools that the costs of maintaining BER buildings will be significant down the track as a result of construction quality issues.

Since these buildings were all constructed at the same time , it is likely they will all require maintenance at the same time. This foreshadows a potential future challenge for DEECD in managing the cost associated with the concurrent deterioration of these assets. Careful planning at the school and portfolio levels will be necessary to avoid significant expense associated with the ageing of BER buildings.

Recommendation

- The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should comprehensively evaluate the delivery and impact of the Victorian Schools Plan and the Building the Education Revolution program, as well as all future infrastructure investments.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development with a request for submissions or comments.

The submissions and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Further audit comment:

Acting Auditor-General’s response to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s (DEECD) response to Recommendation 5 does not make it clear which part of the recommendation it accepts and which it does not. It is also not clear whether DEECD intends to take any action to address the recommendation, and if so, when.

As noted in the report, DEECD has not adequately evaluated the delivery and impact of the $4.5 billion Victorian Schools Plan and Building the Education Revolution programs. The lessons referred to in DEECD’s response do not reflect the outcomes of a comprehensive evaluation. They appear to focus on the funding approaches adopted by the Commonwealth and Victorian governments, not the lessons learned about DEECD’s own planning and administration of the funding and programs. Unless DEECD comprehensively evaluates these and other programs it will have lost an opportunity to leverage the lessons from this major investment, compromising its ability to deliver future school infrastructure programs efficiently, effectively and economically.