Managing Victoria’s Planning System for Land Use and Development

Overview

With the state welcoming about 100 000 people a year, pressure on jobs, housing, infrastructure and other services will intensify. The land use and development planning system is one of the key tools used by state and local governments to meet these demands and deliver the state's priorities for a connected, liveable and sustainable state.

In this audit, we assessed whether the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and councils are managing and implementing the planning system to support the objectives of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the desired outcomes of state planning policies. We focused on the activities of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and three selected councils—the Cities of Whittlesea and Yarra, and Moorabool Shire Council.

We make six recommendations for the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning.

Managing Victoria’s Planning System for Land Use and Development: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2017

PP No 250, Session 2014-2017

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Managing Victoria's Planning System for Land Use and Development.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

22 March 2017

Audit overview

The property industry is the largest sector in the Victorian economy. In 2015–16, more than 57 000 planning permit applications were approved through the planning system, providing for an estimated 46 000 new dwellings and 62 000 new lots. This created about $25 billion of proposed economic investment in Victoria. With the state welcoming about 100 000 people a year, pressure on jobs, housing, infrastructure and other services will intensify.

By its nature, planning is complex. Decisions are multifaceted and demand a holistic, integrated approach by all levels of government to deliver state land use and development priorities. The land use and development planning system is not the only means of achieving government's planning priorities, but it is a centrally important tool used by local and state governments to deliver the state's priorities for a connected, liveable and sustainable state.

If the planning schemes used to manage land use and development across the state are to help achieve this ambition, their focus should be clear and they should be supported by policies that clearly express the state's planning objectives and priorities. If the community is to have confidence and trust in the planning system, decisions must be transparent, and planning schemes must be well implemented and operate as intended.

Planning system objectives and roles

In Victoria, the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (the Act) sets out seven broad objectives for planning-directed sustainable outcomes that are beneficial to both current and future generations.

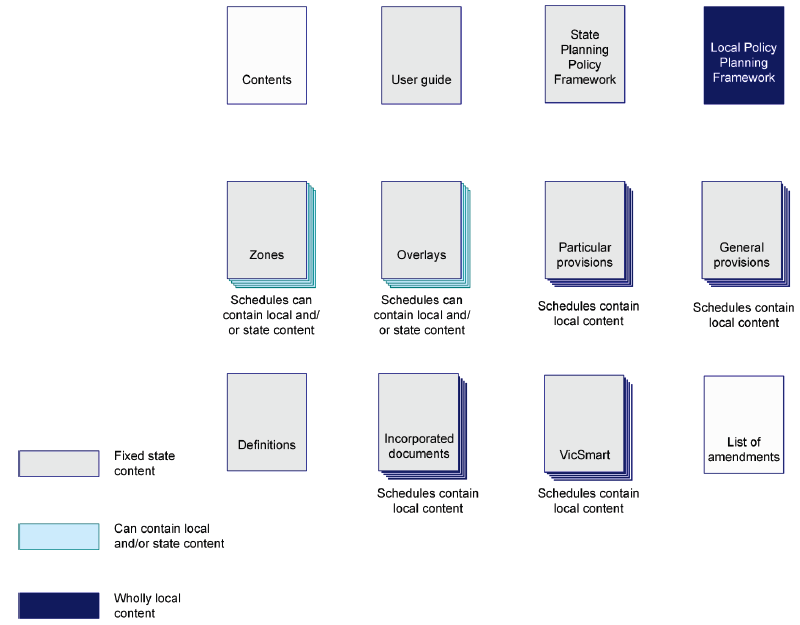

It does this by establishing Victoria's planning system, based on a statewide framework of planning provisions—the Victoria Planning Provisions (VPP)—including policies and controls to be applied through local planning schemes, which guide how different areas can be used and developed. Planning assessments and decisions must support the desired outcomes of state planning policy objectives. They do this by meeting the requirements for integrated decision-making outlined in the Act and the decision guidelines in the VPP.

The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) is the department currently responsible for the state's land-use planning system, managing the regulatory framework and providing advice on planning policy, strategic planning and urban design. DELWP works with local councils to help them prepare and amend planning schemes that reflect their community's needs and expectations for land use and development.

Figure A shows that the planning system has been overseen by various state government departments over the last two decades.

Figure A

Victorian state government departments responsible for planning since 1996

Period |

State government department incorporating planning |

Acronym in report |

|---|---|---|

January 2015 to now |

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

DELWP |

July 2013 to December 2014 |

Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure |

DTPLI |

August 2007 to June 2013 |

Department of Planning and Community Development |

DPCD |

December 2002 to July 2007 |

Department of Sustainability and Environment |

DSE |

1996 to November 2002 |

Department of Infrastructure |

DI |

Source: VAGO.

Councils propose most of the changes to planning schemes—although these are ultimately approved by the Minister for Planning (the minister)—and make most decisions about what land use and development is allowed.

The minister also makes changes to the planning schemes and makes decisions on land use and development in some locations where he or she has the authority to do so. The minister also has the power to intervene in planning matters in any area under defined circumstances.

The minister and councillors, as elected representatives, have considerable discretion in making these decisions. Providing reasons for the decisions they make is a fundamental aspect of transparently exercising this discretion, particularly when the decision goes against the applicant's request.

Past reviews of the planning system

Since 1996, successive governments have sought to reform the planning system. The key objectives of these reforms have been to:

- develop performance-based planning schemes through the introduction of the VPP—a template for policies, controls and other planning provisions to be adhered to by all local planning schemes

- simplify the planning system, particularly its complex system of controls

- improve the efficiency of assessment processes and decisions by streamlining assessment and approval processes and reducing red tape

- review the purpose of the state and local planning policy frameworks and their content

- improve reporting transparency, including the time taken to assess planning proposals.

Our 2008 audit Victoria's Planning Framework for Land Use and Developmentfound that the planning department at the time—DPCD—needed stronger oversight of the planning system and of the uptake and impact of these reforms. It highlighted also that DPCD and councils needed to improve their administration of the planning permit and planning scheme amendment processes.

The scope of this audit

In this audit, we assessed whether DELWP, and councils in their roles as planning and responsible authorities, are managing and implementing the planning system to support the objectives of the Act and the desired outcomes of state planning policies.

We also examined:

- progress since our 2008 audit in improving oversight of the system and its performance

- the impact of reforms since 2008 in improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the land use planning system

- barriers to the delivery and implementation of better-practice planning schemes

- the approach to measuring the planning system's performance.

We looked specifically at how well DELWP advised the minister through its assessments and how well it managed the planning system. We also examined the activities and assessments of three councils—the City of Yarra, the City of Whittlesea and Moorabool Shire Council. These provide examples respectively of an inner city, an outer metropolitan and a peri-urban or 'interface' council (one of the nine municipalities that form a ring around metropolitan Melbourne).

Conclusion

DELWP and the three councils we audited are not being fully effective in their management and implementation of the planning system.

Governments, state planning departments and councils have directed significant effort over many years to reform and improve the system. Despite this, they have not prioritised or implemented review and reform recommendations in a timely way, if at all. The assessments DELWP and councils provide to inform decisions are not as comprehensive as required by the Act and the VPP. DELWP and councils have also not measured the success of the system's contribution to achieving planning policy objectives.

As a result, planning schemes remain overly complex. They are difficult to use and apply consistently to meet the intent of state planning objectives, and there is limited assurance that planning decisions deliver the net community benefit and sustainable outcomes that they should.

Our examination showed that planning schemes have mixed success in achieving the intent of state policy across the three areas we examined—developing activity centres, increasing housing density, diversity and affordability, and protecting valuable agricultural land.

Clearly much more work is required if the system is to realise its intent. A key focus must be simplicity—which can be achieved by clarifying the purpose of the system and eliminating ineffective controls. This should facilitate a shift in mindset away from a controls-based approach toward a more mature, outcomes-based consideration of all relevant, potentially conflicting, risk factors and impacts.

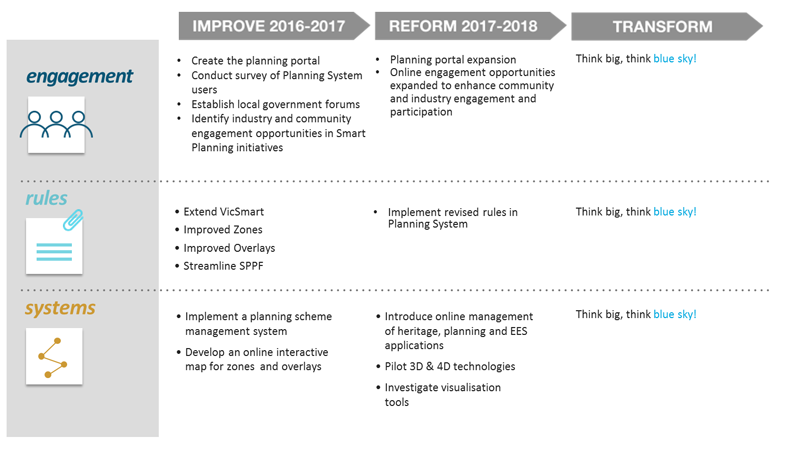

Encouragingly, government and DELWP have developed a $25.4 million reform program to overhaul and improve Victoria's planning system. The program has been designed to address many of the outstanding issues from previous reviews and audits, and should provide a springboard for delivering a simplified and effective planning system. It is critical that this is supported by updated guidance materials and training to ensure the sustainability of reforms across all administrators and users of the system.

Findings

Reforming the planning system

Government, planning departments and councils have continually reviewed and reformed the planning system since our last audit of the system in 2008.

Successful reform initiatives have resulted in:

- streamlined processes for approving a small number of low-risk planning scheme amendments and planning permit applications

- improved information exchange between planning authorities, referral authorities and applicants by clarifying processes, information requirements and timelines

- updated guidance materials in the form of planning practice notes and ministerial directions to improve the content and application of planning schemes

- the introduction of revised planning application fees and development levies that more accurately reflect the cost of planning proposals

- more transparent and comprehensive reporting of the system's efficiency in processing development proposals.

Past reforms have had little impact on fixing other systemic problems impeding the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of planning schemes. As a result, many of the issues prevalent before the 1996 overhaul of the planning system have re-emerged: These include:

- vague and competing state planning policy objectives and strategies, with limited guidance for their implementation, which reduce the clarity of the planning system's direction in meeting state planning objectives

- a lack of specific guidance to address key planning challenges, such as social and affordable housing, climate change and environmentally sustainable development

- an overly complex system of planning controls in local planning schemes—councils add and amend policies and controls to try to provide clarity and certainty to their schemes in the absence of clear guidance at a state level

- DELWP's and councils' performance measurement frameworks being unable measure whether the objectives of the Act or state planning policies are being achieved

- lengthy delays in the processing of planning proposals, leading to set time frames not being met and unnecessary costs for applicants.

These systemic weaknesses exist because of the poor uptake and implementation of review recommendations. This is due to:

- a lack of clear prioritisation, time frames, actions or resources to support the implementation of recommendations by planning departments or government

- a lack of continuity in reform processes and commitment to their implementation due to changes in government or government policy

- poor project governance and oversight, with frequent machinery-of-government changes to the planning department and its systems, and the absence of a good project management structure to oversee the implementation of recommendations.

As a result, the planning system is difficult to navigate and implement, and it places an unnecessary burden on local government, DELWP and applicants to administer and use.

The state government has funded a $25.4 million overhaul of the planning system—the SmartPlanning Program—that DELWP is delivering over the next two years. Specific projects, if implemented well, should address many of the key issues identified in this audit—delivering a streamlined state planning policy framework, model planning schemes, improved zones and overlays, and an improved electronic system for managing and sharing planning information.

Its implementation is supported by strong project governance and monitoring frameworks—features that have been absent in past reform processes.

DELWP has not yet finalised the business case or secured funding for rolling out the complete program of reforms to councils and other users of the planning system. Completing these actions is critical to the success and sustainability of the reforms.

Barriers to better planning schemes

A better-practice planning scheme is clearly focused, easy to use, transparent, responsive to changing planning demands and community expectations and supported by efficient administrative processes. These features are outlined in DELWP's revised 2015 User Guide for the Planning System, the ministerial direction for the Form and Content of Planning Schemes and a range of DELWP practice notes guiding the form and content of local planning schemes.

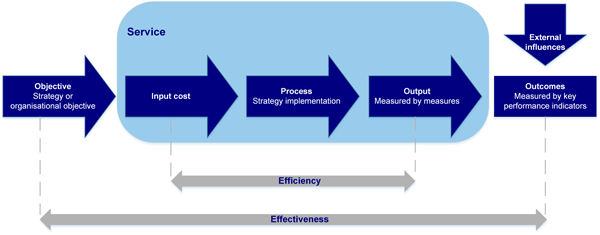

A scheme's efficiency, effectiveness and ability to deliver cost-effective outcomes should also be regularly monitored, evaluated and reported.

Victoria's planning system has features that support these better-practice principles:

- its structure creates a focus on policy outcomes and provides a logical hierarchy of policy from the state to the local level, and the ability to group and align state and local policy themes

- the state's planning framework provides a consistent set of planning provisions that must be included in all local planning schemes

- DELWP has introduced a wide range of materials to guide the form, content and application of a performance-based planning system—including guidance to improve the system's focus on policy outcomes and limit the use of prescriptive provisions.

In practice, however, the system is still not meeting DELWP's better-practice principles in a number of areas:

- User friendly—planning schemes are not user friendly due to their lack of clarity and guidance, and overly complex system of controls that are difficult to navigate and engage with.

- Clearly expressed strategic vision—local planning schemes allow a clearly expressed strategic vision through their municipal strategic statements but the state's planning framework—the VPP—has no strategic vision to help integrate and prioritise its nine policy themes and over 87 policy objectives or connect it to the strategic state and regional priorities, such as those identified in Plan Melbourne (2014).

- Consistent planning provisions—planning provisions across the state are consistent, but weak oversight and failure to deliver review recommendations by planning departments and councils mean a number are out of date, ineffective or repetitive, such as requirements for car parking and advertising signs.

- Transparent—there is generally strong community participation due to extensive third-party and appeal rights in planning decisions. However, planning assessments used to inform decisions do not transparently analyse all relevant planning matters as required by the Act and the VPP, and not all decisions are accompanied by published reasons.

- Efficient—the system is not yet meeting efficiency expectations, as time frames for completion of planning assessment processes are generally not achieved, resulting in unnecessary delays and costs for applicants.

- Responsive—the amendment process and the structure of the VPP encourage a performance-based and flexible approach to determining planning proposals. However, the system's effectiveness in addressing current and emerging planning challenges is hindered by a lack of guidance at the state level. Some councils are also slow to review and revise local planning schemes, and there is no requirement for DELWP to regularly review and revise the content of the VPP.

Government reforms and DELWP guidance have aimed to create performance-based planning schemes and administration—with a focus on meeting policy outcomes rather than administering a system of planning controls, and with prescription as the exception.

Literature and departmental guidance indicate that control-focused administration of planning schemes is less responsive to changing land use needs and community expectations. It also creates more burden on councils and DELWP to assess a large number of development applications and frequently amend land use schemes to address emerging issues and changes in conditions.

Councils and DELWP are now incorporating a mix of performance- and control-based approaches to applying planning schemes. However, our examination of assessment reports informing council and minister decisions showed that the balance continues to favour control-based approaches.

Our audit, DELWP's 2016 examination of state planning controls, and reviews of local planning schemes by councils, all show the policy basis of local planning schemes is overshadowed by an overly complex system of planning controls.

This unnecessary complexity is due to:

- local controls being continually added to local planning schemes to provide certainty and clarity due to a lack of guidance, vague policies and objectives and gaps in the state's planning framework

- the inclusion of a number of local planning controls that do not effectively support the intent of state policy planning objectives

- the large numbers of planning controls that are repetitive, outdated, conflicting and ineffective.

We found examples where councils and DELWP inconsistently or incorrectly used and applied planning controls to manage flooding risks, contaminated land, housing and activity centres.

DELWP has indicated it will address many of these barriers to a better-practice planning system and local planning schemes, identified in this audit, by delivering the government's $25.4 million overhaul of the planning system.

Efficiency

We found that the process for assessing planning proposals has been improved since our last audit of the planning system in 2008 by:

- improving transparency about time frames for statutory processes and decision‑making

- streamlining statutory processes for amending a small number of low-risk scheme amendments and permit applications

- reducing the ministerial authorisation step of the process to 10 days to allow public exhibition of scheme amendments

- streamlining the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) appeal process and the Planning Panels Victoria assessment process

- improving the efficiency of referral processes and information exchange between planning authorities, referral authorities and applicants

- increasing the transparency of responsible authorities'reporting on the processing of planning permit applications.

However, slow decision-making continues to undermine the system, as the majority of planning scheme amendments and permit applications are not processed within current time requirements.

This is partly due to the absence of a comprehensive risk-based approach to assessment. DELWP has taken steps to base the assessment and approval processes more on risk since 2008. It has streamlined assessments and approvals for some low‑risk planning scheme amendment proposals and planning permit categories.

Risk-based assessment processes are not fully incorporated into the planning system to ensure applications are progressed in a timely manner in proportion to their risk, scale and complexity. Efficiency indicators for planning proposals do not set targets for and measure elapsed time in a consistent and transparent way that reflects the potential risk, impact and complexity or cost—and in accordance with community expectations.

Streamlining of low-risk proposals will be further developed over the next two years through the Smart Planning Program. This initiative needs to be further extended to comprehensively explore risk-based planning assessment processes.

The quality of planning assessments

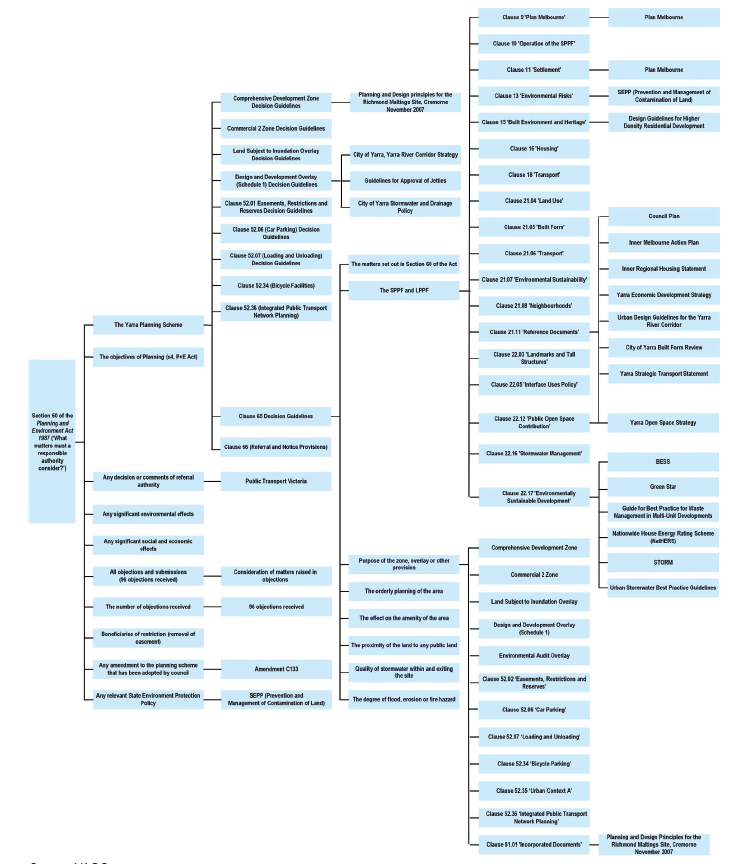

DELWP and council planners provide assessment reports to the minister, the minister's delegate in DELWP and the council to inform their decisions on planning scheme amendment proposals and planning permit applications. We examined how well the assessment reports considered selected key decision-making elements as required under the Act and the VPP. These elements included integrated decision-making, net community benefit, sustainable development and acceptable outcomes.

The quality of planning assessments by DELWP and the three councils had significantly improved compared to the assessments we reviewed for our 2008 audit. However, they still did not comprehensively demonstrate compliance with the key requirements of the Act and the VPP, and transparently document the balanced, integrated assessment needed.

Nor did they adequately address the objectives in the Act or the six state planning policy themes we examined.

Assessments that were not comprehensive were inadequate due to a number of reasons:

- assessment against state planning policies is difficult due to the vague policy objectives and lack of measurable indicators

- gaps in statewide guidance on challenging planning issues, such as housing diversity and affordability

- no statewide guidance on what the Act's concepts of net community benefit, sustainable development and acceptable outcomes cover, and how they might be assessed in a way that is in proportion to the scale, complexity and risk of the planning proposal being considered

- limited consideration of potential adverse environmental, social and economic factors

- in-house assessment report templates that do not adequately reflect the requirements of the Act or the VPP for integrated decision-making.

DELWP is responsible for checking whether draft proposals to change planning schemes are sound, but it does not always check accurately or require the appropriate adjustments. Around one-third of the planning scheme amendments we reviewed did not have sound strategic justification. This was because DELWP's check did not:

- analyse the need for change against all relevant strategic priorities

- identify when proposals applied state or local policy inappropriately

- identify when proposals applied planning tools incorrectly.

The limitations in the documented assessments informing planning decisions and DELWP's checks on draft amendment proposals weaken confidence that planning decisions adequately meet the requirements of the Act and the VPP.

Accountability and transparency of assessments and decisions

For the planning scheme amendments we assessed, DELWP and the audited councils publicly exhibited those they needed to and referred them to affected stakeholders and referral authorities, as required by the Act. Those that they did not exhibit had been appropriately exempted from this process.

Councils' responses to community submissions on amendments and objections to permits on the files we reviewed were appropriate and transparent. However, DELWP did not record its responses to objections in a quarter of the assessments we reviewed. As a result, we could not verify that these decisions appropriately considered and responded to comments from the community.

It is important for decision-makers to have a level of flexibility or discretion in applying laws and requirements, to be able to account for individual circumstances and the needs of the wider Victorian community. Better practice in exercising this discretion is to publish reasons for decisions, particularly those that go against the original request.

The actual decisions of councils and the minister on amendments and permits are made public, but the reasons for the minister's decisions are less transparent because the minister does not have to meet the same transparency requirements as councils:

- councils publish planners' assessment reports—which usually provide reasons for decisions—however, reasons were not published in seven of the 48 permits and three of the 15 amendments where councils decided to oppose the planner's recommendation

- most of the minister's decisions are not supported by published assessment reports or reasons—for example, only 18 per cent of all planning permit application assessments in 2015–16 were published—and advisory committee reports, which can provide reasons, are published at the minister's discretion.

The reasons for ministerial interventions also are not fully transparent:

- DELWP publishes the reasons for all interventions but in two of the six interventions we examined, the published reasons did not clearly justify the intervention

- DELWP's 2004 planning practice note on Ministerial Powers of Intervention in Planning and Heritage Matters committed the minister to reporting annually to Parliament on each intervention, but since 2011 the planning ministers have not done so.

DELWP advised that this practice note is being reviewed.

Measuring the planning system's performance

In 2008 we recommended that DPCD introduce a performance measurement framework to measure and evaluate the effectiveness of the planning system and the reforms to it.

DPCD, DTPLI and DELWP have implemented few of the recommendations from our 2008 audit, and as a result DELWP is still not measuring:

- the achievement of local and state planning policy outcomes and evaluating the effectiveness of reforms

- the effectiveness of the VPP in ensuring certainty and consistency in decision‑making

- performance in managing and supporting the state's planning system.

DPCD introduced a monitoring and reporting framework in 2010, but its focus is mainly on the efficiency of planning permit processes.

DELWP measures some aspects of the performance and progress of the planning system and publishes reports and data from these on its website. However, these measures have not been designed to ensure that, collectively, they provide the information needed to measure the planning system's key objectives. These include measures in strategies, plans and programs—including Plan Melbourne (2014) and its Urban Development Program reports—and the process and system output measures proposed in DELWP's Smart Planning Program.

The councils we audited did not have measures in place to monitor how their local planning schemes were performing.

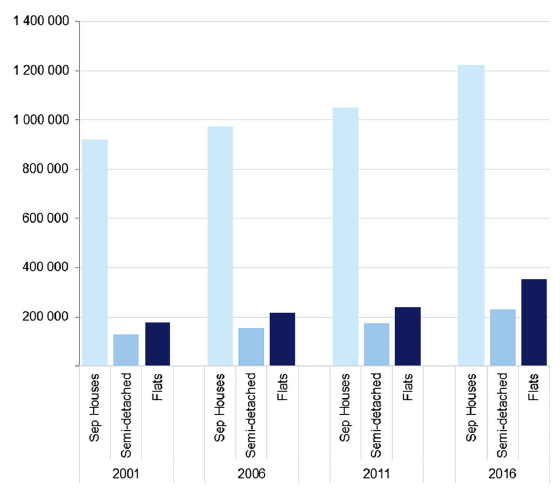

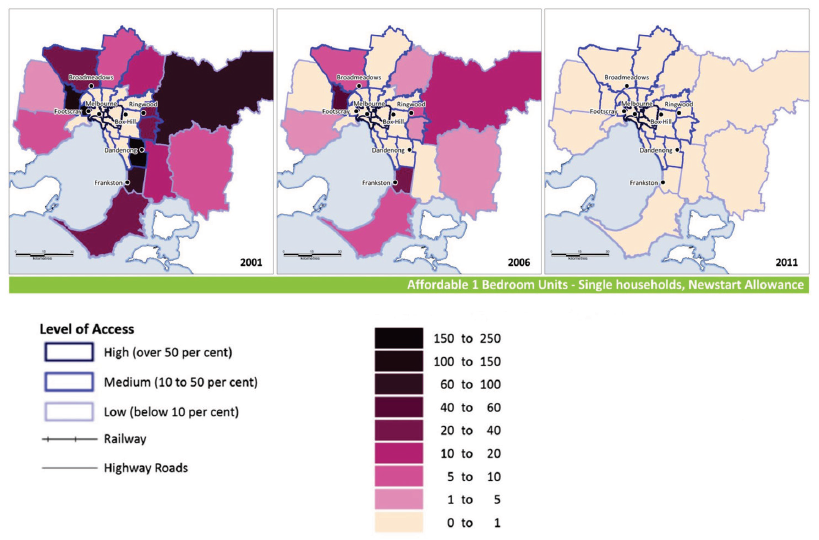

We found—through analysing data provided by DELWP and from publically available data sources—mixed success in achieving the desired outcomes in the three state planning policy themes we examined.

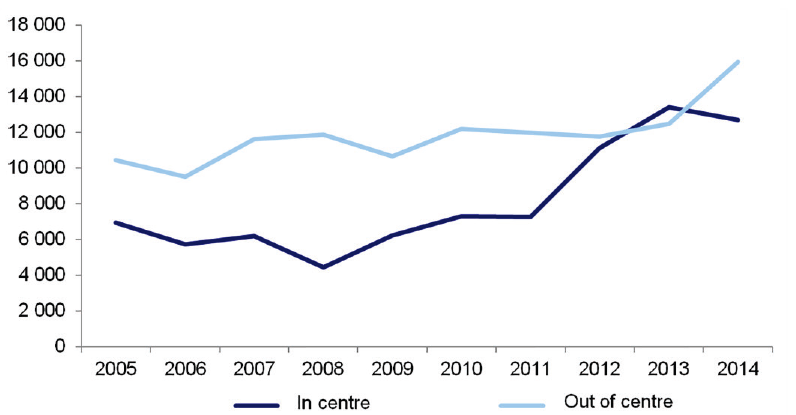

Councils are achieving increasing success in developing activity centres and increasing housing density in accordance with state planning policy objectives, but are making mixed or slower progress in improving housing diversity and affordability, and in protecting valuable agricultural land.

As the planning system is only one influence in meeting state planning priorities—although a key one—it is hard to assess how much the application of the planning system has contributed to these outcomes or lack of outcomes without a performance measurement framework.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

1. ensure its Smart Planning Program improves the planning system by:

- updating, simplifying and clarifying the content of the Victoria Planning Provisions in line with the weaknesses identified in this audit

- developing a business case for Stage Three of the Smart Planning Program, to successfully roll out all reforms and ensure they are adequately resourced (see Part 2)

2. strengthen its approach to overseeing and continuously improving the planning system, by:

- incorporating a requirement in the revised Victoria Planning Provisions for its regular review

- facilitating the development of a technical committee to undertake regular reviews of the Victoria Planning Provisions and its content

- reviewing the roles, responsibilities and guidance for undertaking and implementing local planning scheme reviews in a timely manner based on risk

- strengthening the planning scheme amendment process by providing a robust check of the strategic justification of amendments and the legal basis for the chosen planning provisions at the authorisation stage

- working with councils to ensure that existing planning controls for natural hazards, such as flooding, fire and erosion, are applied in all areas where they need to be to appropriately manage the risks (see Sections 2.2.1, 4.2.1 and 4.2.3)

3. work with councils to improve the way it and councils apply the requirements of the Victoria Planning Provisions, through:

- improving the capacity of departmental and council planners to apply the planning scheme and assess planning proposals comprehensively against the requirements of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the Victoria Planning Provisions

- developing and implementing training materials to educate planners to apply a performance-based approach to the application of the planning system and assessments

- requiring assessments to include an overall conclusion that integrates the decision-making considerations, weighing up the positive and negative attributes and the overall acceptability of the proposed land use or development in proportion to its scale, complexity and risk (see Sections 4.2.2 and 4.2.3)

4. introduce a risk-based approach to development assessment processes and guidance materials, by:

- developing clear, simple assessment pathways that ensure applications are progressed in a transparent way in proportion to the potential risk, impact and cost, and in accordance with community expectations

- reviewing efficiency indicators to support the application of a risk-based approach (see Section 2.2.2)

5. strengthen accountability requirements for decisions by applying better-practice principles for discretionary decision-making and transparent public reporting, including publishing reasons for all planning decisions, and publishing advisory committee reports within three months of the committee handing its report to the Minister for Planning (see Sections 4.2 and 4.3.1)

6. work with councils to complete the performance measurement framework for the planning system so that it provides the relevant information and data at the state and local levels to assess the effectiveness of the planning system, measure the achievement of planning policies and support continuous improvement of the planning system through monitoring the effectiveness of reforms (see Section 5.2).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Cities of Whittlesea and Yarra, and Moorabool Shire Council, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by Section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions and comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

DELWP accepted the recommendations we made to it. The Cities of Whittlesea and Yarra supported the intent of the recommendations we directed to DELWP and agreed to work with DELWP to improve the planning system. Moorabool Shire Council confirmed the accuracy of the report.

1 Audit Context

Victoria has a statewide statutory planning system to regulate land use and development. The system's broad objectives are to protect the physical and cultural amenities of communities, and preserve natural resources and the environment, while responding appropriately to the need for development.

The property industry—including all aspects of developing, selling and operating residential and non-residential property—is the largest sector in the Victorian economy. In 2015–16, this sector formed 11.9 per cent of the Victorian economy and directly generated 273 000 full-time equivalent jobs.

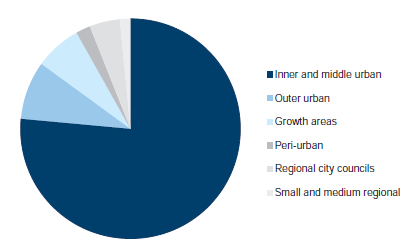

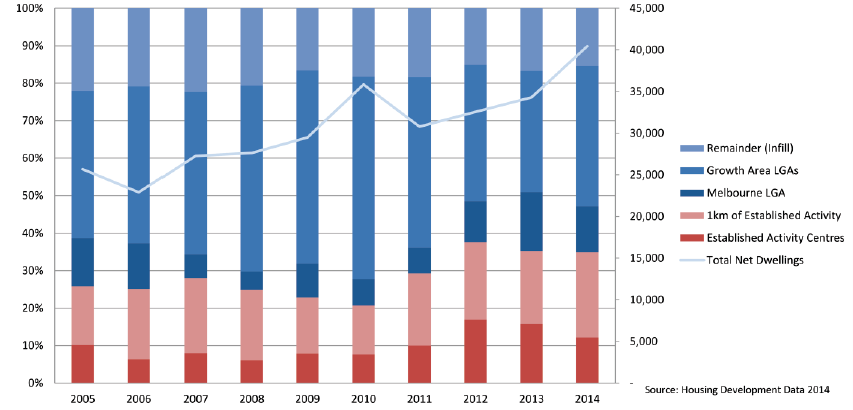

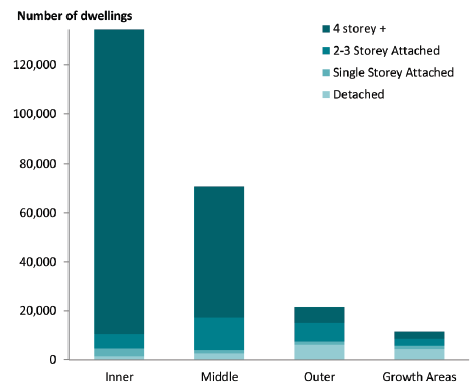

About $25 billion of proposed economic investment passed through the planning system in 2015–16, involving more than 57 000 planning permit applications for an estimated 46 000 new dwellings and 62 000 new lots. Most of the sites of these dwellings and lots are in established areas in metropolitan Melbourne, as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Proportion of new dwellings in permit applications, across council subgroups

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

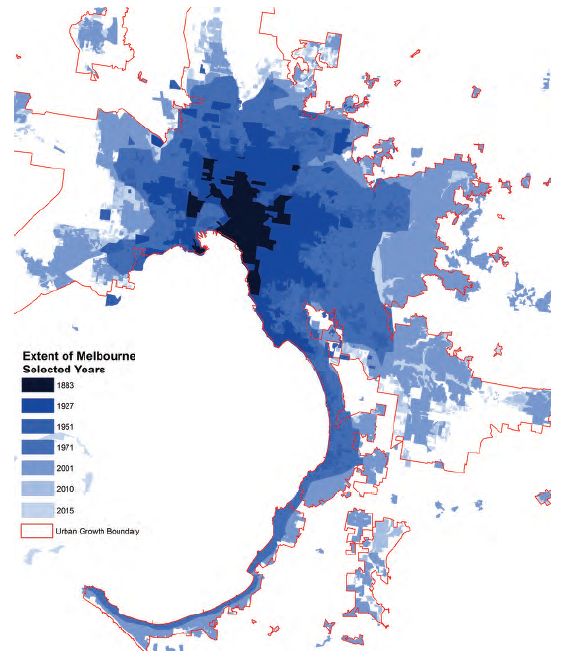

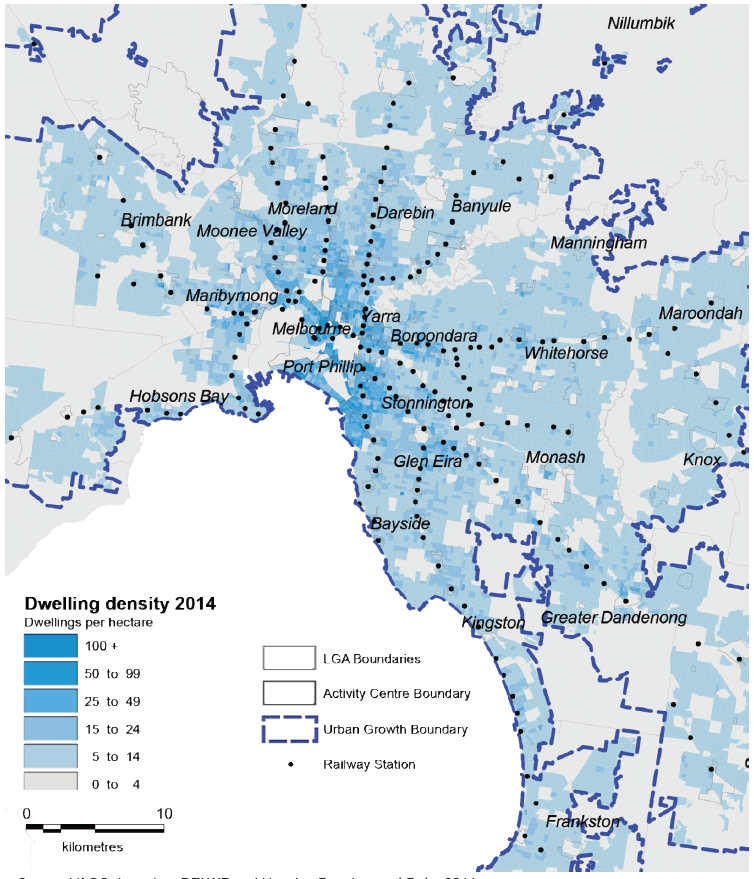

Between the 1920s and the 1970s, metropolitan Melbourne expanded significantly, as shown in Figure 1B. Recent governments have sought to curb the spread and instead channel growth into higher-density development in established areas and in the regional cities, particularly using the urban growth boundary set in 2002.

Figure 1B

Melbourne's expansion, 1883 to 2015

Source: DELWP.

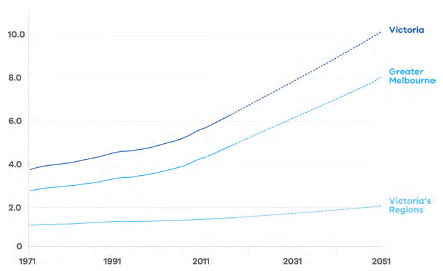

Victoria's population grew from 5.5 million in 2011 to about 6 million in 2016, and is expected to reach 10 million by 2051, with most growth in the greater Melbourne area within the urban growth boundary, as shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Victoria's population, estimated to 2051, in millions

Source: Victoria in Future 2016, DELWP.

With the state welcoming about 100 000 new people each year, pressures on jobs, housing supply, infrastructure and other services will intensify. The demands of growth are intrinsically tied to land use and the ability of the planning system to efficiently respond to changes without compromising economic, environmental and liveability outcomes.

In Victoria, planning for land use and development is controlled mainly through the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (the Act) and the Planning and Environment Regulations 1988. The current planning system has been developed to reflect the requirements of the Act and to deliver its objectives, as outlined in Figure 1D.

All planning decisions must comply with the objectives of the Act and the planning framework. To achieve this, the planning system requires the assessments that inform decisions to integrate all relevant policies and planning matters. Assessments must also balance conflicting policy objectives in favour of net community benefit and sustainable development for the benefit of present and future generations. Analysis must be transparent, based on evidence and address all relevant planning matters.

This is particularly important under the current performance-based planning framework, which allows discretion in planning decisions, guided by policies and subject to specific controls.

Figure 1D

The objectives of the Planning and Environment Act 1987

|

Planning objectives, section 4(1)

|

|

Planning framework or system objectives, section 4(2)

|

Source: VAGO, from the Planning and Environment Act 1987.

The planning system must also provide procedures for dealing efficiently with land use and development proposals. As planning decisions can have a substantial effect on people's lives and on commercial developments, it is essential that these procedures deliver timely and sustainable planning outcomes. A planning system that achieves this is more likely to gain the confidence of Parliament and the wider community.

1.1 The state planning system

Land use decisions are complex and multi-faceted, and require an integrated approach by all levels of government, and across government tools, to deliver state priorities. The land use planning system is one of the key tools used by local and state governments to meet these demands and deliver the state's priorities for a connected, liveable and sustainable state.

To do this effectively, planning schemes must be clearly focused, and policies must clearly express state's planning priorities and objectives. The planning schemes must be supported by effective and efficient processes for their implementation. This must all be done transparently, within the constraints of a politicised environment, to help ensure the community's confidence and trust in the planning system to deliver sustainable outcomes.

The planning system provides a strategic and policy framework to integrate and balance often conflicting policy objectives and economic, social, and environmental considerations. It seeks to ensure that there are fair, orderly, responsive and transparent processes to manage the economically productive and sustainable use of land in Victoria. The planning system in Victoria controls:

- land use—using land for a particular purpose, such as a dwelling or a shop

- development—constructing, altering or demolishing a building or works, and subdividing or consolidating land.

It does this through the planning system established by the Act. The key parts of this system include:

- the Victorian Planning Provisions (VPP), which set out the template for the construction and layout of planning schemes

- local planning schemes, which set out how land may be used and developed

- the procedures for preparing and amending the VPP and planning schemes

- the procedures for determining planning permit applications lodged under the planning scheme

- the procedures for settling disputes and enforcing compliance with planning schemes, and other administrative procedures.

The Act also sets out the planning objectives for the state as well as the outcomes of the planning system for the use, development and protection of land, as detailed in Figure 1D.

Each municipality in the state is covered by a planning scheme. Planning schemes set out policies, objectives, and controls for the use and development of land in a given area.

Planning schemes must continue to evolve and respond to changing factors that influence land use and development. Planning schemes must also respond to today's key planning challenges, even though some of these challenges—such as climate change, ecologically sustainable development and housing affordability—are complex, require an integrated whole‑of‑government approach to manage, and are without simple solutions.

At the same time, the planning system is a key tool among many for implementing government policy. Planning schemes may be amended so that they remain relevant to changing needs and directions in the state or local context, by introducing further policies, objectives and controls.

Planning schemes can be amended in several ways:

- by the Minister for Planning (the minister)

- by councils and agencies appointed by the minister—although they must get the minister's approval for the changes before beginning the amendment process

- by land owners requesting an amendment—although there is no legal obligation for their request to be considered.

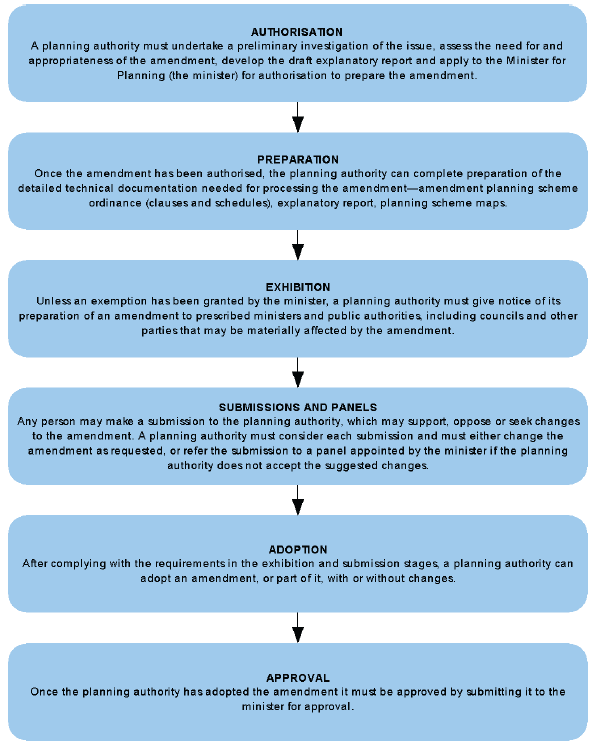

Amendments to planning schemes can have significant implications and affect the wider community because they can change the way land may be used or developed. The process for amending a planning scheme is prescribed in the Act, and involves all parties who may have an interest in the amendment, or may be affected by it. The minister must approve all amendments to planning schemes.

Planning permits allow a particular use, development or subdivision of a parcel of land. The planning permit application and assessment process aims to ensure that:

- land use is appropriate for the location

- buildings and land uses do not conflict with each other

- the character of an area is not adversely affected

- development will not detrimentally affect the environment or an area's amenity

- places of significant heritage value are not demolished or detrimentally changed.

A planning permit for a particular proposal may be required under a given planning scheme.

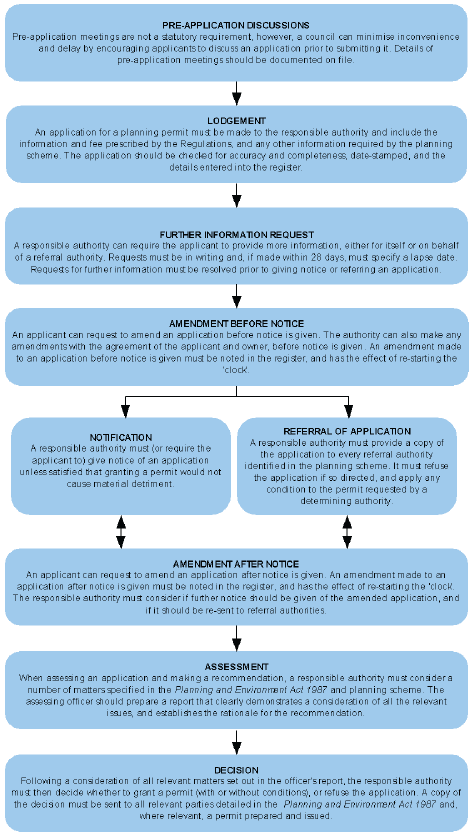

Appendix B outlines the components of a planning scheme as well as the decision‑making processes for planning scheme amendments and planning permits. The time frames and procedures for processing planning permit applications and planning scheme amendment proposals are specified in the Act and regulations.

1.2 Key players

Planning authorities develop and amend planning schemes to give direction on how state planning policies will be achieved or implemented in the local context.

Responsible authorities manage the day-to-day administration of the local planning scheme. They consider and determine applications for planning permits, ensure consistency with the planning scheme and enforce conditions included in planning permits.

Councils

Councils are responsible for local planning schemes. In most cases, the local council—or their delegated officer(s)—is both the planning and responsible authority.

The Minister for Planning

The minister is a planning authority and may amend any planning scheme. The minister is also the responsible authority in some designated areas and for some classes of permit applications, such as wind energy applications. The minister can direct another government agency, such as VicRoads, to be a planning authority for an amendment. DELWP supports the minister to fulfil his or her responsibilities as a planning and responsible authority under the Act.

The minister has overall responsibility for the state's planning legislation and framework, and has the power to grant exemptions from legislative requirements, make directions to planning and responsible authorities, approve planning scheme amendments, and decide cases where there is an issue of state or regional significance.

The state planning department

DELWP is the department currently responsible for the planning system, which has been overseen by various state government departments over the years, as shown in Figure 1E.

Figure 1E

Victorian state government departments in charge of planning since 1996

|

Period |

State government department incorporating planning |

Acronym in report |

|---|---|---|

|

January 2015 to now |

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

DELWP |

|

July 2013 to December 2014 |

Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure |

DTPLI |

|

August 2007 to June 2013 |

Department of Planning and Community Development |

DPCD |

|

December 2002 to July 2007 |

Department of Sustainability and Environment |

DSE |

|

1996 to November 2002 |

Department of Infrastructure |

DI |

Source: VAGO.

In this role, DELWP:

- manages the regulatory framework for land use planning and provides strategic and statutory guidance and advice on planning and urban design

- manages the ongoing development and maintenance of the Act, regulations and the VPP on behalf of the minister.

Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal

The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) deals with disputes about assessments and decisions on planning permit applications. Parties aggrieved by the planning decisions of responsible authorities may appeal to VCAT for a review of the decision. VCAT is an independent review tribunal, and its decisions are legally binding.

Planning Panels Victoria

Planning Panels Victoria gives independent advice to councils and the minister on planning scheme amendments referred to it. It also gives those who make submissions—usually opponents to a proposal—an opportunity to be heard in an independent forum, although it is not a court of law and its decisions are not legally binding.

1.3 Past reviews

In our previous audit reports—Land Use and Development in 1999 and Victoria's Planning Framework for Land Use and Development in 2008—we made a number of recommendations to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the planning system.

There have also been numerous reviews and reforms of the land use planning system since 2008. Most have focused on the efficiency of the system and its specific parts—such as the state policy framework and individual planning controls—rather than focusing on the effectiveness of the entire system in achieving the objectives of the Act and the intended outcomes of state planning policies. These reviews and reforms are listed in Appendix C.

1.4 Why this audit is important

There is substantial investment in land use planning and development in Victoria, and it is important to provide assurance to Parliament and the community about whether:

- the state's objectives for planning and the planning system are being achieved

- the planning system is being implemented effectively, efficiently, transparently and accountably

- reforms to the planning system have worked as intended.

Effective oversight of the land use planning system—including performance monitoring and reporting—is essential to provide Parliament, developers and the public with confidence in the system.

It is now timely to assess the effectiveness of the reforms implemented since 2008 to address the gaps identified in our 2008 audit and other reviews.

1.5 What this audit examined and how

Our objective was to assess whether DELWP and councils are effectively managing planning schemes and the planning permit system in accordance with the objectives of the Act, and whether this has achieved the intended outcomes of state planning policy.

In our previous audits in 1999 and 2008, we focused on the amendments to the land use planning framework and the system's efficiency. Stakeholders raised many matters with us about the effectiveness of the land use planning system in delivering sustainable outcomes.

In this audit, we focused more on how effectively the land use planning system delivers sustainable outcomes that are within its influence, and how this is overseen, monitored, evaluated and reported on at state and local levels. We also considered how effectively key amendments have addressed identified gaps.

To do this, we examined a selection of planning assessments of land use and development proposals from four audited agencies, and whether they resulted in sustainable outcomes that are beneficial to current and future Victorian communities. We looked at the roles of DELWP and selected councils in delivering these outcomes. We also examined DELWP's role as the minister's delegate for planning and responsible authority decisions, and the advice it provided to inform the minister's decisions.

We examined how planning authorities consider the advice they receive from planning panels and ministerial advisory committees. We did not look at VCAT's role in the planning system, although we considered data that related to its planning decisions.

We looked in detail at the City of Yarra, the City of Whittlesea and Moorabool Shire Council. These three councils face a range of planning challenges and represent three different council types—respectively inner city, outer metropolitan and peri-urban (on the interface or boundary between metropolitan Melbourne and the rural areas).

Our audit focused, where possible, on the following areas from the state and local planning policy frameworks, selected to cover a range of policies and include policies that stakeholders had advised us presented some challenging issues:

- protecting valuable agricultural and farming land

- managing flooding and inundation risks

- developing activity centres

- increasing housing diversity, density and affordability

- supporting environmentally sustainable development

- managing potentially contaminated land.

We carried out the audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $605 000.

1.6 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 assesses the success over time of efforts to improve the planning system

- Part 3 looks at the barriers preventing the planning system from reaching best practice

- Part 4 examines the quality of the assessments that councils, DELWP and the minister use to inform their decisions on planning scheme amendment proposals and planning permit applications

- Part 5 examines how the performance of the planning system is measured and what this shows about success in achieving the objectives of the Act and of selected state policies.

2 Reforming the system

The planning system operates in a complex environment. Population growth pressures continue to place demands on infrastructure, services and the environment. Changes in economic performance and property industry trends affect land use and development demands. Community expectations of what the planning system can address and achieve also continue to change and grow.

The planning system must respond to these changing demands and expectations. This is best achieved through regular and systematic review and reform of the planning system. The government and the lead agency for planning in Victoria—the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP)—play an important role in ensuring this happens.

This Part of the report examines planning system reform and its success since our last audit of the planning system in 2008.

2.1 Conclusion

Successive governments, state planning departments, and local councils have conducted many reviews of Victoria's planning system since 2008. Many of these have been inefficient, and have used significant resources for limited obvious gain in addressing the key systemic weaknesses in the effectiveness and efficiency of the planning system.

The slow uptake and reduced impact of reforms is mainly due to disruption to their implementation and to key review processes. This is caused by changes in government and government policy, and planning departments' past inadequate prioritisation, implementation and oversight of review recommendations.

One-off reviews have led to improvements in specific elements of the system's content and streamlining steps in the statutory processes, but have not addressed the systemic issues identified as early as 2000 of overly complex local planning schemes, and weaknesses in the content of the state's framework—the Victorian Planning Provisions (VPP).

As a result, planning schemes are difficult to navigate and costly to administer, which delays decision-making.

Encouragingly, the government and DELWP have begun to implement a $25.4 million reform program to overhaul, simplify and modernise Victoria's planning system. The program has been designed to address many of the outstanding issues identified in past reviews and VAGO audits, and should lead to a more mature, simplified planning system.

To ensure the benefits of the reforms are successfully implemented, Stage Three of the Smart Planning Program, to roll out the reforms to all stakeholders, must be funded and resourced appropriately.

2.2 Past reviews and reforms

The state has approached planning reform with notable vigour since 2008, with key reforms listed in Appendix C. Reforms to improve the effectiveness of the planning system have focused on:

- the VPP—the template for all planning schemes, which includes state planning policy objectives, strategies and policy guidelines and, planning controls and other provisions

- the legislative framework and streamlining statutory processes

- improving the cost-effectiveness of the system.

The overall purpose, role and content of the planning system have not been holistically reviewed since its last major reform in 1996. Since then, there have many incremental additions and amendments to the state's planning framework and its local schemes.

Our examination of key ministerial, government and VAGO recommendations for the reform of the planning system since 2008—discussed in further detail in the following sections—shows that less than half of the recommendations have been implemented successfully or achieved their intended outcomes.

This is because:

- accepted recommendations have not been implemented before further reform processes have been introduced, due to a change in government or government policy

- planning departments have not prioritised, supported and resourced the implementation of accepted recommendations

- continued machinery-of-government changes to planning departments have affected the implementation and sustainability of reforms

- departmental oversight of the planning system has been poor as there is no regular systematic review of the system, the VPP and their effectiveness

- factors influencing the use and development of land, and community expectations of the system, have also changed.

DELWP—as the administrator of the system—does not regularly monitor or evaluate the uptake and effectiveness of reforms as part of its overall performance and evaluation framework.

As a result, there has been much work and investment for little effective gain in fixing the key systemic weaknesses of the planning system. These weaknesses were identified as early as 2000 and are impeding the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the system in delivering timely and sustainable planning outcomes.

Unacceptable delays in decision-making persist, and planners and applicants continue to have difficulty navigating and using the system, increasing the unnecessary burden on both council resources and applicants.

In 2008, we recommended the planning department at the time—the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD)—set up a structured performance and evaluation framework that included monitoring and evaluating the implementation of reforms.

In 2010, DPCD implemented a performance measurement framework. Its focus, however, is on indicators that measure the efficiency of administrative services and assessment processes, rather than on monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of reforms and the system in meeting the objectives of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (the Act) and the intent of state planning policies. As a result, both DELWP and our audit team have been unable to accurately assess the effectiveness of successfully implemented reforms.

2.2.1 Review and reform of the Victoria Planning Provisions

Reforms of the VPP since 2008 have contributed to improvements in:

- providing a framework of consistent policy outcomes for incorporation in all planning schemes

- general alignment of state and local policies

- consistent structure for local schemes

- the ability to tailor policies and controls to local conditions

- planning controls that provide improved outcomes for a number of specific issues, such as bushfires

- updated guidance materials in the form of practice and advisory notes.

However, fewer than half of the recommendations from ministerial and planning committee advisory reviews have been implemented to address the weaknesses in the role, purpose and content of the VPP, identified as far back as 2000. Specific issues with the current content of the VPP and its application are discussed in the sections that follow.

These problems persist due to inadequate departmental oversight of the planning system, and the lack of an effective monitoring and evaluation framework for measuring and assessing the uptake and effectiveness of reforms. There is no requirement for DELWP to regularly conduct a systematic review of the VPP and its effectiveness in supporting the implementation of state planning priorities. In contrast, councils have a legislative requirement to review the content of their local planning schemes every four years.

The state planning policy framework

Since 2008, the structure, role, purpose and content of the State Planning Policy Framework (SPPF)—which includes the state's planning policy objectives and their strategies and policy guidelines—has had four reviews, listed in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Reviews of the state planning policy framework

|

Reform or review initiative |

Progress in delivering reforms |

|---|---|

|

2009 ministerial committee review of the planning system |

Revised SPPF implemented in 2010. Problems continued due to vague and competing policy objectives and strategies, with limited guidance for their implementation. |

|

2011 ministerial committee review of planning schemes |

Eleven recommendations made to address continuing issues with the 2009 revised SPPF—six out of 11 recommendations implemented. |

|

2012 Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission Inquiry into Streamlining Local Government Regulation |

Two recommendations made to revise the role, structure and content of SPPF. Government accepted recommendations, but only elements of the recommendations were partly implemented. |

|

2013 ministerial committee review of the SPPF |

Fifty recommendations made, including developing a new Planning Policy Framework (PPF). Government's response to the review not published and no recommendations implemented. Draft PPF shelved due to issues identified by DELWP in 2015. |

|

2017 proposed departmental review of the SPPF |

Review to begin as part of the government's Smart Planning Program. |

Source: VAGO.

The significant effort, money and time spent to improve the purpose, role and implementation of the SPPF since 2008 has had limited impact in resolving unmet need for:

- clarity in state planning policy objectives

- measurable objectives to support policy implementation

- guidance in balancing numerous competing policy objectives and strategies

- specific guidance addressing key planning issues, such as climate change and environmentally sustainable development.

Poor uptake and implementation of recommendations is not delivering cost-effective outcomes. Although DELWP could not provide the specific costs of the reviews listed in Appendix C, the average cost for a ministerial committee review taking 12 to 18 months—including legal, research and stakeholder consultation—was approximately $1.56 million in 2012–13. This would indicate that reviews of the SPPF alone since 2008 may have cost about $6 million or more, with little effective impact.

In 2014, the government was elected on a policy platform of further reforming the SPPF. The reform project is to be delivered as part of government's $25.4 million Smart Planning Program to overhaul and simplify the planning system. We discuss this in detail in Section 2.3.

State planning controls

There has been mixed success in modernising and improving the clarity of planning controls to support the implementation of state planning policy objectives through specific one-off reviews. Recommendations from only five out of 13 reviews we examined have been fully implemented.

Overall, state planning departments have been slow to act on recommendations from one-off reviews of specific controls, if at all (see Appendix D). DELWP does not systematically review the planning controls—zones and overlays—in the VPP for their effectiveness in implementing state planning policy objectives and their responsiveness in addressing emerging planning challenges. This is despite the recommendations from our 2008 audit report and a 2011 ministerial committee that an ongoing advisory committee be established to regularly consider and review issues associated with the system of controls. In addition, planning departments have not taken a risk-based approach to prioritising reviews and their recommendations.

As a result, weaknesses in planning controls continue to affect the clarity and responsiveness of local planning schemes to key planning challenges, risks and changing community expectations, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Case studies—Planning control reviews

|

Car parking controls The review into car parking planning controls first began in 2007, with recommendations implemented in 2013 resulting in an amended car parking overlay. Many of the councils outside the metropolitan region have not introduced this overlay due to the cost and time associated with it for little gain. Councils argue that VPP clause 52.06, the state's higher order control, requires updating to allow flexibility in achieving sustainable parking outcomes, without relying on the overlay provisions. Residential zones The first residential zones review began in 2007 and revised zones came into effect in 2013. Between 2007 and 2013, three ministerial committees reviewed the zones, with little change to the first committee's recommendations. Recommendations were either not adopted or not implemented until 2013. Based on the cost of a 12 to 18 month ministerial committee in 2013, the total cost for this process is indicatively estimated to be $4.5 million plus DELWP's costs. Flood controls In 2012, after reviews of bushfire and flood controls, DPCD began including hazard maps in local planning schemes to better inform their implementation and to manage bushfire and flood risks. The government funded this initiative in the program Improved Responses to Hazards in 2012–13, at a cost of over $1 million for bushfires and $574 000 for floods. Hazard maps have generally been successfully added to planning overlays, although not by all councils. Flood-related overlays need to be updated by councils so that they are applied to all flood-prone areas in the state, as shown in Appendix E. Contaminated sites DPCD asked for $934 000 from the State Budget to implement the recommendations from our 2011 audit report Managing Contaminated Sites and the 2012 ministerial review to improve planning tools to manage contaminated sites. DELWP advised us that the previous government placed a hold on this work and the problems identified with these tools remain unresolved, creating a potential public health and environmental risk. |

Source: VAGO.

Local planning policy frameworks—council reviews

The Act requires each council to review its local planning policy framework (LPPF) no later than one year after its council plan is approved under section 125 of the Local Government Act 1989, which is generally every four years. This is to ensure that the local planning schemes are up to date, and consistent with the VPP and departmental guidance.

Councils' compliance with this legislative requirement has been inconsistent. We looked at a sample of 17 LPPF reviews. It showed the majority of the 17 local planning schemes are not up to date or compliant with the ministerial direction for the Form and Content of Planning Schemes.

We found that the content of 12 of the 17 schemes has not been updated because of late reviews or poorly implemented recommendations. Only four of the 17 councils we looked at have implemented key recommendations from their reviews. Eight have yet to implement recommendations from reviews that began more than four years ago, despite their next review being either now due or overdue. Details of our analysis are outlined in Appendix F.

As a result, elements of local planning schemes are out of date, they do not fully address key planning challenges, and they are not as responsive as they should be in addressing emerging risks.

Poor compliance with this legislative requirement is due to:

- lack of timely reviews by councils

- poor implementation of review recommendations by councils

- unclear responsibilities and time frames for the implementation of review recommendations

- limited council resources due to the backlog of planning proposals

- the cost of the review process and its implementation.

Councils must prepare formal planning scheme amendments to implement changes recommended by each review. The councils we examined have taken between one and six years to prepare and adopt amendments, which is not compatible with the requirement to regularly review the LPPF every four years.

The lack of clarity about responsibilities for the assessment and approval of LPPF reviews contributes to the often excessive time taken to implement recommendations.

Councils must submit reviews of their planning schemes to the Minister for Planning (the minister), but the minister is not clearly responsible for doing anything with this review or for providing timely advice. A number of councils indicated they received a letter but with no specific advice.

Councils are not required to implement review recommendations within a specified time frame.

Two rural councils indicated they would not undertake a comprehensive review of their planning scheme due to the excessive cost quoted for this task—$90 000 to $100 000—compared to their planning budget. Other councils had undertaken and paid for these reviews but not implemented recommendations due to the issues discussed above, and a lack of resources.

Moorabool Shire's budget for the delivery of statutory planning services was $659 000 in 2015–16. While no figures are available on the specific costs of processing planning scheme amendments, Moorabool calculated that the average planning permit cost council $2 129 to process during this period. It processed approximately 400 applications at an approximate cost of $851 000. This leaves no statutory planning budget funds available to undertake the planning scheme review.

In 2013, a Municipal Association of Victoria submission into the proposed revision of the SPPF estimated the gap between revenue and cost for statutory planning services was about $3.5 million for metropolitan councils and about $2.7 million for regional councils.

The government has acted on a range of planning revenue issues over 2015–16 to address this gap. Actions include the 2016 Planning and Subdivision Fees and Regulation review, and a new system of standard levies that are pre-set for particular development settings and land uses, which better reflect their cost.

2.2.2 Reforming the regulatory framework

Since our last audit of the planning system in 2008, planning departments have expended significant time and resources on reforms to the regulatory framework. These reforms have contributed to improvements in:

- streamlining statutory processes for amending low-risk scheme amendments and a small number of low-risk permit application categories

- streamlining the ministerial authorisation process for the public exhibition of proposed planning scheme amendments

- documenting transparent time frames for planning assessment processes

- streamlining the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) appeal process and the Planning Panels Victoria assessment process to reduce appeal and hearing waiting times and costs

- more effective application of referral processes and information exchange between planning authorities, referral authorities and applicants

- more transparent and comprehensive reporting on development proposals by DELWP and councils.

However, a number of legislative reforms to improve the effectiveness of decision‑making processes have only been partially effective in resolving the problems they were intended to fix, as outlined in Figure 2C and discussed further below.

Figure 2C

Success of amendments to the Act

|

Date |

Amendment |

Success in addressing the issue |

Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2013 |

Required assessors to take account of social and economic impacts as well as environmental impacts |

Partially |

Analysis of assessment reports indicate impacts are noted but not comprehensively identified and integrated in decision‑making processes. |

|

2013 |

Replaced development assessment committees, introduced in 2009, with planning application committees to help councils assess projects of regional significance or complexity |

✘ |

No planning application committees have been used by councils. The audited regional councils indicated that they still lacked timely departmental support in providing advice on regionally significant projects. |

|

2013 |

Created two classes of referral authorities—including a 'determining referral authority'—and required them to assess applications against the Act's objectives |

Partially |

This produced a more transparent referral authority process and more efficient information exchange but our examination of referral comments showed limited evidence that referral authorities assess the application against the Act's objectives. |

|

2015 |

Requires responsible authorities and VCAT, where appropriate, to consider the number of objectors when determining whether the use or development may have a significant social effect |

Partially |

Although the amendment made it mandatory for responsible authorities and VCAT to consider the number of objectors, this has not added any clarity about when a social impact is significant and should be taken into account in the decision-making process. |

Source: VAGO.

Improving the assessment of social impacts

The Planning and Environment Amendment (Recognising Objectors) Act 2015 (the amending Act) was introduced to require the two key decision-makers in the permit process—responsible authorities and VCAT—to consider, where appropriate, the number of objectors when assessing whether a proposal may have a significant social effect.

The amendment has not added any clarity about when a social effect should be considered significant—which was one of the key issues leading to this amendment. The Act, the VPP and DELWP's guidance materials also provide little clarity about this issue. The 2015 Parliamentary Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry into the Planning and Environment Amendment (Recognising Objectors) Bill identified these concerns before the Bill was adopted.

There is also a lack of clarity between the amending Act, the planning scheme decision guidelines in clause 10.04 of the VPP and the ministerial direction about whether a social effect has to be significant to be taken into account in the decision-making process.

The Act states that before deciding on an application, the planning or responsible authority must consider any significant social and economic effects that it considers the use or development may have. The ministerial direction and Planning Practice Note 46 Guidelines for Strategic Assessment do not refer to significant effects, but states the amendment must adequately address any environmental, social and economic effects.

The economic, social and economic effects of a proposal are usually assessed by considering whether or not the amendment results in a net community benefit. This was rarely done in the assessment reports we examined, as identified in Part 4.

As a result, there is still a lack of clarity—mostly in the community—about social effects and the role objections play in determining whether a social effect is significant in land use and development decision-making processes.

Supporting councils to assess complex planning proposals

An amendment in 2009 to introduce development assessment committees (DAC) was intended to encourage better partnerships between state and local government, and improve local government resources and expertise in assessing land use and development proposals of regional significance or high complexity.

In 2013 the new government replaced DAC with planning assessment committees (PAC), and committed a budget of $2 million over two years to implement these committees. However, only one DAC was ever set up and no PAC is yet to be established.

Councils advised that the PAC terms of reference lack clarity about such factors as who bears the costs of obtaining advice from a PAC and the time lines for setting one up and providing advice. This has influenced the audited councils' decisions not to seek support from a PAC.

Councils advised us that reasons for assessment processes not meeting required time frames were partially due to large workloads compared to resourcing levels and, in the case of regional councils, the time taken for small regional DELWP offices to give advice to councils on more complex planning proposals.

Moorabool Shire Council indicated that DELWP has only one part-time planner available to give planning advice to all municipalities in the region.

In 2011, government set up the $9.4 million Rural Council Planning Flying Squad initiative to advise and support regional councils on complex planning matters and provide immediate support with planning permit and scheme amendment work. From 2011 to 2015, the Flying Squad supported 44 rural councils delivery of 143 regional planning projects. An independent review by SGS Economics and Planning in 2016 estimated that the Flying Squad delivered a cost benefit ratio of $1:3, and the program was cited as leading practice by the Australian Productivity Commission.

The Flying Squad program was not funded past 2015. It was replaced by $2.1 million in funding in 2016–17 to provide councils with access to tools and skills to enable them to complete detailed planning work. The regional councils we audited indicated this did not adequately address the lack of resources and skills to manage the backlog of work and resolve complex proposals.

In February this year, the government announced a further three-year investment of $16.4 million to support councils. The aim is to accelerate planning and approval processes to ensure the supply of new housing in Victoria meets the annual demand. This is part of the government's Streamlining for Growth program to reduce red tape and encourage housing development in key areas.

Improving the timeliness and cost-effectiveness of planning assessments and decisions

Reforms have been implemented since our 2008 audit to improve the transparency and timeliness of statutory assessments and decisions.

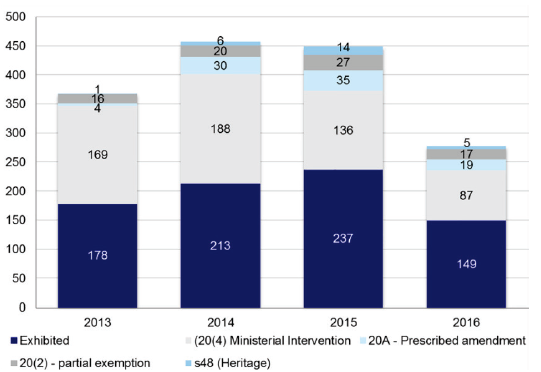

A 2010 ministerial direction now sets a 60-day processing time to make a decision to adopt or abandon a proposed planning scheme amendment after submissions close, 10 days for the minister to authorise a proposed planning scheme amendment for public exhibition and 40 days for the minister to approve an amendment when a local planning authority adopts it. The requirements of the 2015 Planning and Environment Regulations effectively place a 60-day processing time frame on permit decisions.

Although these reforms have improved the transparency about time lines for decisions, times are still not being met for a significant proportion of planning proposals, as shown in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

Planning system performance indicators

|

Category |

2015–16 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Number of planning permits requiring decisions |

56 701 |

|

|

Median number of days to make a decision on a planning permit |

All responsible authorities |

69 |

|

Whittlesea City Council |

113 |

|

|

Yarra City Council |

117 |

|

|

Moorabool Shire Council |

73 |

|

|

Average number of days DELWP took to make a decision on a planning permit |

202(a) |

|

|

Decisions decided in statutory time frame of 60 days for permits (per cent) |

Whittlesea City Council |

61 |

|

Yarra City Council |

44 |

|

|

Moorabool Shire Council |

40 |

|

|

DELWP |

13(b) |

|

|

Decision by minister to adopt a planning scheme amendment within 40 days after being referred by councils—Ministerial Direction 15 (per cent) |

32(c) |

|

|

Average days for minister to adopt a planning scheme amendment as a planning authority |

86(c) |

|

|

Average number of days taken by the minister to approve a planning scheme amendment after being referred by councils—ministerial approval |

87 |

|

(a) These were on hold for unspecified periods.

(b) Timeliness could only be calculated for 40 per cent of all decisions in 2015–16 as DELWP did not routinely collate and analyse the data.

(c) Average of all amendments decided in 2015 and 2016.

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DELWP and Know Your Council website.

In 2015–16, 40 to 61 per cent of permit decisions by the councils met the 60-day approval time. In 2015–16, the minister and DELWP, as his delegate, took an average of 202 days to make a decision, and decided only 13 per cent of permit applications within 60 days.

The minister determined the 14 permits that took the longest time to approve—254 to 580 days.

Between 2013 and 2016, the minister and the planning department, as his delegate, decided on one-third of planning scheme amendments within the required 40 business days after councils submitted them for approval. The average was 87 days. No data was available from DELWP or councils for the average or median number of days taken to process a planning scheme amendment.