Market-led proposals

Overview

In a market-led proposal (MLP), the private sector makes an unsolicited approach to government for support to deliver infrastructure or services through direct negotiation rather than a competitive procurement process. The state has considered many MLPs since early 2015, with four successfully advancing through the entire process to contract award.

We examined whether MLPs are assessed in accordance with government requirements. To address this, we examined the assessment of two MLPs that the government awarded contracts to—the West Gate Tunnel (WGT) and the Victoria Police Centre (VPC). We also reviewed the assessment of alternative proposals for these projects and a proposal received for the development of a unique disease surveillance system and production of disease prevention products for Victoria that was rejected in 2018.

Transmittal letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2019

PP No 95, Session 2018–19

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Market-led Proposals.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

27 November 2019

Acronyms

| AFP | Australian Federal Police |

| BCR | benefit-cost ratio |

| CBA | cost-benefit analysis |

| CBD | central business district |

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DJPR | Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

| DoT | Department of Transport |

| DPC | Department of Premier and Cabinet |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| ESTA | Emergency Services Telecommunications Authority |

| HPFV | higher productivity freight vehicles |

| HVHR | high value high risk |

| IDC | interdepartmental committee |

| IRP | Independent Review Panel |

| MLP | market-led proposal |

| NGTSM | National Guidelines for Transport System Management |

| NPV | net present value |

| PPP | public-private partnership |

| PSC | Public Sector Comparator |

| SOE | state-owned enterprise |

| SSP | Shared Service Provider |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VFM | value for money |

| VPC | Victoria Police Centre |

| VPPSS | Victorian Police Physical Security Specifications |

| WACC | weighted average cost of capital |

| WGT | West Gate Tunnel |

| WTC | World Trade Centre |

Audit overview

Context

What is a market-led proposal?

In a market-led proposal (MLP), the private sector makes an unsolicited approach to government for support to deliver infrastructure or services through direct negotiation rather than a competitive procurement process. The private sector usually asks the government for financial support, but may also ask for regulatory or other forms of assistance.

The state has considered many MLPs since early 2015, with 14 progressing beyond the second assessment stage and four successfully advancing through the entire process to contract award.

How they are assessed

In early 2015, the government established a new guideline and five-stage process for considering MLPs and gave commitments:

- that proposals must meet a series of important tests and be in the public interest to proceed

- that proposals will only proceed if they represent a genuinely unique idea or proposition, deliver on government objectives, provide benefits to the community and achieve value for money (VFM) outcomes

- to uphold the highest levels of integrity and transparency when assessing MLPs.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has a key role in overseeing the MLP guideline and the application of the assessment process. It leads Stage 1 and Stage 2 of proposal assessment in consultation with relevant departments. During Stages 3, 4 and 5, the government-approved lead department, which can also be DTF, undertakes the assessment. When another department or agency leads an assessment, DTF provides support.

The Treasurer is the responsible minister for the MLP guideline. DTF or the Treasurer approves the Stage 1 assessment outcome. The government approves the assessment outcome at Stage 2 and at each subsequent stage. DTF briefs an interdepartmental oversight committee and the Treasurer throughout the assessment process.

Why this audit is important

DTF receives a steady flow of unsolicited MLPs seeking exclusive negotiations with the state, so the government needs a rigorous and transparent process for assessing these proposals to promote new infrastructure and service ideas, and ensure fairness for proponents and value for the community.

It is important that the MLP process works well so that taxpayers can be confident that decisions by government to engage with a proponent in a non‑competitive way is in taxpayers' best interests and beyond reproach.

Objective and scope

The objective of this audit was to determine whether MLPs are assessed in accordance with government requirements. To address this, we examined the assessment of two MLPs that the government awarded contracts to—the West Gate Tunnel (WGT) and the Victoria Police Centre (VPC). We did not examine implementation of these projects. We also examined the assessment of one alternative proposal received for the WGT and two alternative proposals received for the VPC.

Our original audit scope also included the development of a unique disease surveillance system and production of disease prevention products for Victoria. The MLP for this was submitted in June 2017 and rejected at the end of Stage 2 in June 2018. We did not evaluate this in depth, because our initial inquiries indicated that DTF assessed the proposal in accordance with the MLP guideline and process.

The departments and agencies involved in assessing these proposals were DTF, the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), the Department of Transport (DoT), the West Gate Tunnel Project, Victoria Police and the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR).

Conclusion

DTF and Victoria Police documented the required assessments of the WGT and VPC proposals and obtained the required government approvals. However, their advice to government could have been more transparent by fully explaining the implications of their assessment approaches, and providing greater assurance about key inputs underpinning the assessments. Not doing this meant decision makers lacked relevant information to fully inform their decisions for significant state projects procured outside a competitive process.

DTF reasonably determined that an element of Transurban's proposal for the WGT was unique. However, DTF and Victoria Police did not clearly demonstrate that the aspects they assessed as unique in the Cbus/Australia Post proposal for the VPC could not have been obtained in the marketplace within an acceptable time frame.

In DTF's assessment of VFM for the WGT, their use of particular revenue assumptions, different approaches to discounting different revenue streams and use of a state benchmark range without a single best point estimate, all had impacts on the assessment outcomes. Given this, we expected DTF's advice to the government to clearly explain why certain assessment approaches were taken and how they impacted the results. We also expected that DTF would have undertaken more checking and sensitivity analysis, commensurate with the WGT project's significance, to better assure themselves of the comprehensiveness of their VFM assessment and advice.

For the VPC, while the proposal met the VFM benchmarks set by the government, this was achieved because the state retained significant risk. Increases to the size and lease term of the VPC increased the risk and whole‑of‑life costs of the proposal for the state. DTF and Victoria Police did not convey the impacts of these changes clearly enough in their assessments and advice to government.

Findings

Uniqueness of the proposals

It is not sufficient for lead agencies to only demonstrate the presence of unique characteristics in an MLP. They must demonstrate that these characteristics provide value and other benefits for government that could not be achieved through a standard competitive process outside of the guideline within acceptable time frames.

There was competition in the market to deliver a WGT and VPC, evidenced by alternative proposals from Cintra Developments Australia (Cintra) for the WGT and from the World Trade Centre (WTC) and another property developer for the VPC.

DTF and Victoria Police advised the government that the WGT and VPC proposals were unique, based on a funding source and security, respectively.

West Gate Tunnel

DTF's advice to government that the Transurban proposal satisfied the uniqueness test was primarily based on Transurban's capacity to access, escalate and extend toll revenues on its existing CityLink concession.

To be commercially viable, the Transurban proposal needed revenue to flow from four sources—an upfront payment from the government, tolling revenue on the new WGT road, additional increases to tolls from its existing CityLink concession, and an extension of that concession for another 10 years. These funding sources were contingent on government actions and Parliamentary support.

The MLP guideline recognises ownership of strategic assets, including rights under an existing contract, as a unique characteristic. DTF reasonably assessed the CityLink escalation funding source as unique because, under the existing CityLink concession, no party other than Transurban could access and increase tolls on CityLink prior to 2035.

DTF advised that funding from the CityLink escalation source was sufficiently material to justify proceeding as an MLP. This funding source made up between 14 and 18 per cent of the total funding sources the state and Transurban identified and estimated for the project.

DTF also determined that revenue from the 10-year extension on the CityLink concession given to Transurban by government was unique. The 10-year CityLink extension made up around 31 percent of the total funding sources the state identified and estimated for the Transurban project.

DTF identified that as revenue from the CityLink concession extension does not begin flowing until 2035, parties other than Transurban may have had challenges raising project finance tied to this funding source on a VFM basis, due to the timing and uncertainty of these cash flows. However, DTF's assessment of uniqueness regarding the extension did not include substantive analysis of granting another private operator access to the CityLink extension or the state taking on the tolling of CityLink itself from 2035.

DTF's assessment of the Transurban proposal as unique, even if considering only the CityLink escalation funding source, is consistent with the MLP guideline. However, the guideline provides no detail on the level of materiality that unique characteristics should possess. Further, DTF did not transparently assess the value of this source of uniqueness to the state compared to the next best alternative available to government such as a competitive process with additional government guarantees.

Victoria Police Centre

DTF and Victoria Police justified the Cbus/Australia Post proposal to build a new police headquarters at 311 Spencer Street, in Melbourne's central business district (CBD), as unique based on the security and co-location benefits provided by the site. The site is next to the City West Police Complex at 313 Spencer Street, with rail lines at its rear which provide security benefits—including perimeter standoff and natural surveillance—that are unlikely to be built out.

However, DTF and Victoria Police did not satisfy the MLP guideline requirement to show that these benefits could not be achieved through a standard competitive process within acceptable time frames. With the expiry of the current lease in July 2020, there was no time pressure in 2015 that called for sole negotiations with a single proponent. There was ample time for Victoria Police to undertake a competitive process and clear evidence of other options for locating a new Victoria Police headquarters.

Advice obtained by Victoria Police clearly identified other sites that could meet its security needs, and its claims of co-location benefits with the City West Police Complex were only superficially specified.

The Stage 2 MLP assessment led by DTF indicated that Cbus/Australia Post were expected to respond to any competitive market process to provide accommodation for Victoria Police after July 2020.

The potential for other proponents to respond to the service need was demonstrated by the state receiving two alternative MLPs to provide a new headquarters for Victoria Police before it signed the lease agreement with Cbus/Australia Post in January 2017.

Service need and benefits

The 2015 interim MLP guideline criteria required proposals to meet a service or project need that is aligned with government policy objectives and priorities and provides benefits to Victorians.

The assessments of the VPC and WGT proposals clearly demonstrated both met a service need.

West Gate Tunnel

The WGT proposal met a need to reduce traffic congestion arising from high population growth.

The government sought to test the merits of the WGT as a standalone project, without regard to the potential involvement of Transurban, by requesting the former Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) develop a business case for the project.

We assessed DEDJTR's business case against DTF's Investment Lifecycle and high value high risk (HVHR) guidelines and found the following deficiencies:

- As also expressed by both the peer reviewer appointed by DEDJTR and the Independent Review Panel appointed by DPC to review the business case, it lacked a reasonable justification for including the Monash Freeway widening works in the WGT project scope, and this scope element improved the benefit-cost ratio (BCR).

- It showed a marginal value proposition for the WGT project on its own and lacked transparency regarding the sensitivity of the BCR for the WGT project scope element. The business case provided to the government only included sensitivity testing results for the combined Monash Freeway upgrade and the WGT project scope. DTF's advice to the government on the business case did not highlight the lack of sensitivity analysis in relation to the WGT project scope element.

- It did not examine a range of alternative project solution options in sufficient depth and therefore did not provide the government with sufficient information to select the right investment option.

- It did not have a sufficiently transparent cost-benefit analysis (CBA), limiting assurance that the risks of double counting or overstating benefits had been addressed. The collective value of 'other related benefits' were not transparently justified in the business case—such as congested travel time savings and higher productivity freight vehicle (HPFV) benefits. That these benefits were greater than the 'core travel time savings', which typically make up most estimated road project benefits, suggests that this risk was present.

Victoria Police Centre

The VPC proposal met a need to accommodate Victoria Police's headquarters in a secure facility following the expiry of their existing lease at the WTC from July 2020.

DTF's Stage 2 assessment of the VPC proposal identified that Victoria Police did not consider their current facility at the WTC a viable option for police headquarters beyond the existing lease term and were updating an options analysis for a new one.

Value for money

The 2015 interim MLP guideline required VFM assessments to compare the final proposal's cost to a state benchmark, either a public sector comparator or a realistic alternative.

West Gate Tunnel

For the WGT proposal to proceed, Transurban needed to be confident that the sum of the project's estimated future revenues would at least equal the sum of its estimated future costs, in present value terms, while delivering a commercial rate of return.

DTF's VFM assessments compared the Transurban proposal to a state benchmark range that was derived by applying a discount rate range to DTF's estimates of the nominal cost and revenue cash flows for the WGT project.

DTF's assessment and advice to the government that the WGT proposal was VFM did not adequately test and disclose the sensitivity of discount rate assumptions and calculations that underpinned the reliability of its assessment. This and limited analysis of alternative funding options means DTF's advice to the government was not sufficiently comprehensive.

Costs

More than 93 per cent of Transurban's design and construction-related costs were tendered out to the market in a competitive process so the VFM risk to the state for this side of the transaction was relatively low.

Revenues

Transurban's revenue estimates valued potential tolls from the new WGT road, additional increases to tolls from its existing CityLink concession and an extension of that concession. These revenue estimates by themselves were not enough to make the project viable for Transurban. It also needed the state to make an up-front contribution.

For the state to assess the WGT proposal as VFM, it needed to be confident about two key things:

- Estimates of tolling revenue—the state needed to compare Transurban's tolling revenue estimates with its own tolling estimates to make sure Transurban's estimates were reasonable. Without knowing this, the state risked paying too much for its up-front contribution, and it risked escalating and extending the tolls on CityLink by more than necessary.

- There were no better alternatives than Transurban's proposal to fund and finance the project.

Analysis of funding options

DTF did not comprehensively assess other approaches to funding and financing the project, such as:

- borrowing through securitisation of future CityLink tolls

- monetising future CityLink tolls through a competitive process.

DTF's assessment approach deprived the government of critical information to support its decisions on whether, and how, to progress the proposal.

DEDJTR's business case for the project did not assess the difference between the costs and benefits of raising funds from tolls on CityLink compared to other state sources of funding such as taxes and charges, borrowing or other monopoly concessions.

Tolling revenue estimates

Transurban and DTF knew that the valuation of the tolling revenue was critical for the proposal to succeed, because those estimates influenced not only the size of the state's contribution but also the respective size and extent of the CityLink toll escalation and extension.

From Transurban's perspective, demonstrating VFM for the state was a balancing act. Transurban had a commercial incentive to undervalue its tolling estimates to strengthen the argument to escalate and extend the CityLink concession. Conversely, if Transurban's tolling estimates were higher than the state's, then this would reduce the state's contribution to the project, making the proposal attractive to the state.

Transurban also faced a real risk that the state would not proceed with the proposal if the state assessed Transurban's forecast tolling revenues as unrealistic and not providing VFM against state benchmarks.

Reliability of the state VFM benchmark

A large proportion of the reported VFM benefits to the state in Transurban's proposal arose from the differences between Transurban's and the state's valuations of future tolling revenue.

DTF rightly obtained its own estimates of revenues to develop its VFM benchmark range.

At the Stage 4 assessment, the state's lower CityLink escalation toll revenue estimate was the major contributor to the overall difference of $272 million in net present value (NPV) between the Transurban proposal and the midpoint of the state's VFM benchmark range. This was because the state's low estimate had the effect of dropping the bottom end of the benchmark range.

Transurban had little incentive to overstate revenue and may have had better information than the state about the traffic flows underpinning its revenue estimates on CityLink. DTF's Stage 3 assessment report noted that Transurban's ownership and operation of the CityLink concession provided it with in-depth knowledge of the revenue, costs and risks that no other party had.

Where Transurban's estimates were higher than the state estimates, DTF's assessment and advice would have been more comprehensive had it used the Transurban estimates as a sensitivity test and shared the results with government. It did not.

Traffic demand forecasts

The forecasts of traffic demand and the selection and application of discount rates drove the differences in the two valuations of future tolling revenue.

Those differences were most noticeable in the valuations of the CityLink escalation revenues.

The lower end of the state's benchmark range for the CityLink escalation revenues was 65 per cent less than Transurban's estimate, driven by an assumption that 6 to 7 per cent of traffic would be diverted off CityLink. DTF's Stage 4 assessment did not discuss the possibility that the state benchmarks undervalued the CityLink escalation revenue.

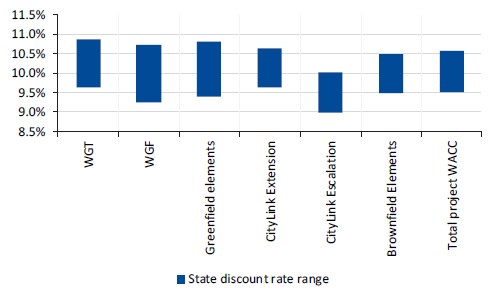

Discount rates

Discount rates are important because, like interest rates, they express the value of money at a particular time. Organisations use them in discounted cashflow analyses as a method of valuing a project. To determine the NPV of a project in today's dollars, its estimated future cashflows, revenues and costs are discounted at a rate, the discount rate, that represents the cost of funding.

DTF applied different discount rates to its estimates of the WGT project revenues and costs to derive a benchmark range against which it could assess the VFM of Transurban's proposal. However, DTF did not explain in the Stage 4 VFM assessment why it applied the discount rates differently for the CityLink escalation revenue. Specifically, it did not explain why the nominal CityLink escalation revenue figures used in the state benchmark were discounted using the reverse of the discount rates they applied to all other revenue estimates. Not explaining this was an omission because the state VFM benchmark was sensitive to the CityLink escalation revenue low-traffic scenario.

Discount rate sensitivity of VFM state benchmark range

DTF's commercial adviser discounted a single set of nominal cashflows using a 'high scenario' discount rate and a 'low scenario' discount rate provided by an investment bank engaged by DTF. This produced a 'high scenario' NPV and a 'low scenario' NPV for each stream of nominal cashflows, which determined the range for the state's VFM benchmarks.

DTF advised that the discount rate range reflected uncertainty around the true commercial rate of return appropriate for this project that was largely caused by the risk and uncertainty involved in forecasting the future toll revenues. However, it is unusual to express discount rates solely as ranges, without also determining a best single point estimate within the range. Adopting this approach meant it was unclear whether all points in the range were equally likely and understanding this would have been useful given the Transurban proposal did not represent VFM at all points in the range. DTF advised that the uncertainty in estimating project toll revenues meant that a best single point estimate would have been inherently unreliable.

Most of the WGT project's design and construction costs occur in the first five years of the project, but the revenues are spread over the 29-year life of the project. A slight change in the discount rate applied to estimated future revenues annually over 29 years makes a significant difference to the present value of those cashflows.

This means that the state's VFM benchmark range was highly sensitive to the discount rate range and any discount rate changes.

Transurban used its estimate of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) as its discount rate. The WACC represents the weighted average expected return to debt and equity investors.

The discount rates that informed the state's VFM benchmark range were generally higher than the rate Transurban used, so the state estimated higher commercial rates of return than those adopted by Transurban.

In an investment of this scale, where the discount rate was so influential to the outcome, the reasons why the state's assumed required commercial rates of return was generally higher than Transurban's should have been set out explicitly and unambiguously in the VFM assessment by DTF. They were not.

DTF should have performed a sensitivity analysis to challenge key assumptions underpinning the state's VFM assessment, and to support the state securing the best possible outcome. We have not seen evidence that this testing and challenge occurred.

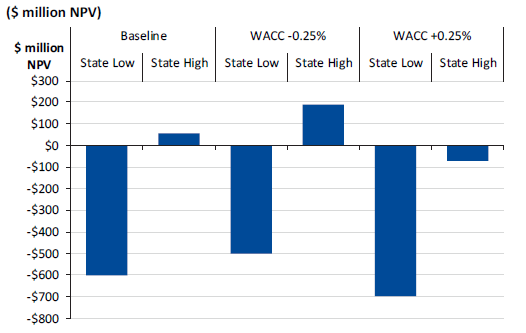

Issues with the state contribution

Transurban's proposal involved a state contribution of $1.96 billion in present value terms, mostly towards design and construction costs.

Transurban calculated the size of the state contribution in its proposal as the nominal amount needed to ensure the project achieved an NPV of zero after delivering its required expected commercial rate of return for the project. Transurban derived this figure using a discount rate reflecting its commercial rate of return that it applied to all other cashflows in its proposal.

The VFM assessment adopted the nominal state contributions proposed in Transurban's final offer. These nominal state contribution cash flows were then discounted in the VFM assessment using the state's estimates of a commercial rate of return.

A commercial rate of return was not the right discount rate for the non‑commercial risks associated with the part of the design and construction costs funded by state contributions to the project. There was no commercial risk to Transurban for the $1.389 billion of nominal state contributions towards design and construction costs that the state had agreed to pay. The discount rate for this part of the project should have been a risk-free rate, which was far lower than the commercial rate of return adopted in the VFM assessment. Applying the correct discount rate to the state contributions cash flows related to design and construction costs would have reduced the VFM of the Transurban proposal.

Lack of transparency over basis and reasonableness of assumptions underpinning the state's discount rate estimates

The discount rates used in the state's VFM assessment were highly sensitive to assumptions and calculations DTF's investment bank made about them, such as the rate of return equity investors require in commercial toll roads. The basis for these assumptions is not clear and it was not possible to determine whether those input assumptions are reasonable.

DTF provided us with evidence that it had interactions with its investment bank about the discount rate issues. However, the extent of scrutiny DTF applied to the investment bank's assumptions was unclear from the material DTF provided.

Advice to the government

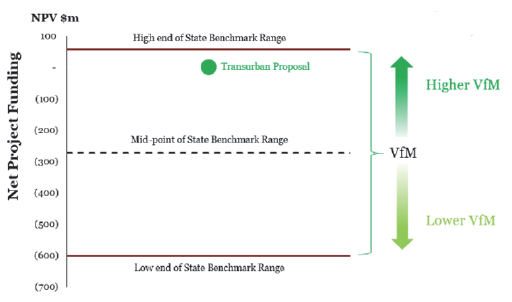

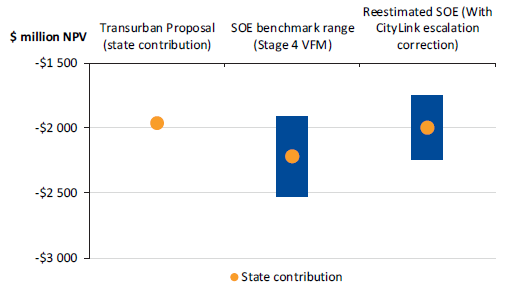

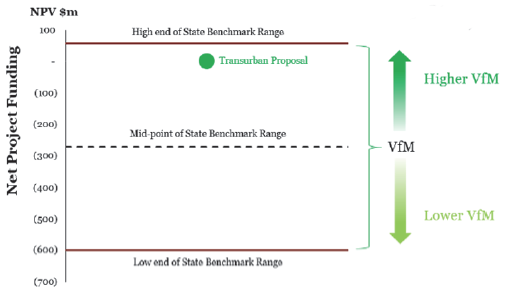

DTF's advice to the government on the Stage 4 VFM assessment results showed the Transurban proposal as having an NPV of zero dollars. The figure below shows how DTF presented Transurban's proposal to the government.

Figure A

Presentation of Stage 4 VFM assessment results to the government

Source: DTF.

DTF's presentation approach showed the Transurban proposal falling within the range provided by the state's VFM benchmarks and meeting the VFM assessment criterion that it needed to be above the midpoint of these benchmarks.

We note that:

- the state's commercial adviser responsible for developing the VFM assessment provided no indication of the likelihoods attached to the 'high' and 'low' state VFM benchmark scenarios and did not express any opinion on the most likely benchmark outcome

- it was probably not the case that any point within the range was equally likely

- the upper and lower bounds of the range were driven very materially by the state's discount rate range, and we have raised questions about the lack of review and transparency over the basis for and reasonableness of assumptions underpinning the discount rate estimates used in the state's VFM assessment.

The VFM assessment analysis and advice to the government would have been more useful and transparent if DTF had provided a single point best estimate of the state VFM benchmark as well as the benchmark range shown in Figure A. The single point estimate should have reflected DTF's best view on the cost to the government of delivering the project itself. The government could have used this estimate as the key comparison point for the Transurban proposal.

Victoria Police Centre

|

DTF's SSP delivers office accommodation and property management services for Victorian Government leased and owned properties including accommodation suitability assessment and selection. |

In early 2015, Victoria Police discussed plans for a competitive process to obtain new accommodation with the Shared Service Provider (SSP) business unit within DTF and would have run an expression of interest in the absence of the VPC proposal from Cbus/Australia Post.

In November 2016, the government authorised the Treasurer and Minister for Police to approve the VPC proposal and lease agreement. This was based on DTF and Victoria Police advice that the proposal provided VFM, including meeting the VFM benchmarks set by the government. The lease agreement commits the state to a 30-year lease with a starting total lease cost of $44.6 million a year.

The 30-year lease is unusually long for a government tenancy and the lease agreement is $14.8 million a year more than the annual lease costs Victoria Police pays for its accommodation at the WTC. Victoria Police plans to recoup some of these costs from sub-tenants.

The increased cost reflects a 30 per cent increase in the accommodation space available when compared to the WTC, to accommodate potential subtenants. In November 2016, none of the proposed subtenants had provided a binding commitment to take up space in the VPC.

The interdepartmental committee (IDC), DTF and the SSP challenged whether the VPC proposal represented VFM for the state throughout the assessment process. These challenges prompted ongoing negotiations with the proponents on key commercial terms and led to changes in the offer.

The government's VFM benchmarks for the VPC specified annual rental costs in total and on a per-square-metre basis, rather than as whole-of-life costs. Victoria Police and DTF provided accurate advice to government on the Stage 4 assessment that the government VFM benchmarks were met. However, the factors that most significantly contributed to this outcome were the:

- increase of the lease term from 20 to 30 years

- increase of the building size from about 42 000 square metres in net lettable area to more than 60 000 square metres to accommodate potential, unconfirmed subtenants.

These adjustments increased the risk and whole-of-life costs of the VPC proposal for the state. Two of the three proposed subtenants withdrew after the state signed the lease agreement. This has left the state exposed to meeting any shortfall in rental costs for the entire VPC building.

Victoria Police continues to work with the SSP to seek other tenants. Actual achievement of the VFM benchmarks is contingent on Victoria Police recouping some of the lease costs from sub-tenants. There is also a risk that other tenants will diminish the security benefits sought by Victoria Police.

Alternative proposals

While the 2015 interim MLP guideline includes the government objective of ensuring a transparent and fair process, it does not include a process that explains how lead agencies should fairly assess 'competing' MLPs for the same project.

The state received two alternative proposals while it considered the VPC proposal from Cbus/Australia Post, one from the owners of the WTC and one from another property developer. The government rejected both at Stage 1—the WTC proposal in November 2016 and the other proposal in January 2017.

The government rejected the WTC proposal based on DTF's assessment and advice that the proposal could not meet Victoria Police's critical security requirements and was unlikely to offer VFM for the state.

While the IDC identified the need for DTF and Victoria Police to assess the WTC and the VPC proposal against the same requirements, Victoria Police did not provide the WTC proponents with the same information on its security specification as it provided to the VPC proponents.

The government also received an alternative proposal for the WGT project from Cintra in October 2015. DTF's assessments of this proposal at Stage 1 and Stage 2 were comprehensive in addressing the requirements and intent of the MLP guideline. In December 2015, the government approved DTF's recommendation that the proposal not progress to Stage 3.

Meeting MLP process requirements

DTF and Victoria Police largely met the MLP guideline requirements for due diligence, probity, governance and approval, consultation and public disclosure for the WGT and VPC proposals.

There were two exceptions.

The only significant non-compliance identified for the WGT proposal was DTF's decision to not publicly disclose details of the Cintra proposal for an alternative WGT project after the Stage 2 assessment of this proposal and decision not to progress it to Stage 3 in December 2015.

The MLP guidelines require public disclosure of summary details of proposals at the end of Stage 2 in the MLP process. DTF advised the government that it would publicly disclose details of the Cintra proposal, but then determined that it would not do so on the basis that it wished to maintain competitive tension with Transurban. DTF disclosed the Cintra proposal on the MLP website in September 2019.

Public officials involved in assessing the MLPs examined in this audit did not document declarations that they had no conflicts of interest during the assessment process. DTF took the view early in the MLP process that departmental and agency staff only needed to complete conflict of interest declarations where there was an actual or potential conflict and did not require a 'positive' declaration of no conflict.

This approach was inconsistent with the conflict of interest declaration form included in DTF's Probity Plan requirements that applied at the time, which provided for positive declarations. DTF advised us that it acknowledges there was inconsistency between the requirements of the plan and the attached conflict of interest form, but confirmed its view that the Probity Plan for Stages 1 and 2 assessments did not require 'positive declarations of no conflict'.

DTF later amended the MLP process to make it clear that public officials need only complete conflict of interest declarations if involved in Stage 2 assessments and beyond, in its updated Probity Plan for Stage 1 and Stage 2 assessments in August 2018.

Improving and supporting the MLP guideline

DTF has actively supported the MLP process by improving the specificity and rigour of the guidance and underlying assessment process since the government first established it in 2014.

The current MLP guideline could be further enhanced to provide guidance on ensuring equity and procedural fairness when assessing 'competing' MLPs for the same project.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance:

1. documents the assumptions and calculations underpinning advice it presents to decision-makers about market-led proposals, including advice provided by third parties

2. undertakes sensitivity analyses to test key assumptions of value for money assessments for market-led proposals

3. clarifies the market-led proposals guidance about:

a. the nature and weighting of primary and secondary sources of uniqueness

b. how material uniqueness benefits need to be to support exclusive negotiations

c. whether agencies should measure uniqueness benefits against a state benchmark or other private providers

d. whether agencies should demonstrate the merits of market-led proposals against a value for money range and/or a point estimate

e. how agencies should assess concurrent alternative market-led proposals.

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DPC, DTF, DoT, Victoria Police and DJPR, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions and comments.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A:

DPC and DJPR noted the report and provided no substantive comments.

DTF did not support the findings in the report and did not accept the recommendations. We have written to DTF's Secretary outlining our concerns with this response.

DoT supported DTF's response to the report in relation to the WGT MLP.

Victoria Police did not accept the report findings on the VPC MLP and supported DTF's response in relation to the VPC.

1 Audit context

In an MLP, the private sector makes an unsolicited approach to government for support to deliver infrastructure or services through direct negotiation rather than a competitive procurement process. The private sector usually asks the government for financial support but may also ask for regulatory or other forms of assistance.

The government issued a new guideline and established a five-stage process for considering MLPs in early 2015 and declared that MLPs would only succeed if found to be unique, VFM and in the public interest.

1.1 Why this audit is important

This audit considers the WGT project and the new VPC. The government procured both projects, which involve significant public expenditure, through MLPs.

MLPs do not result from standard government investment planning and evaluation processes and are not fully tested in a competitive market. While the MLP process may elicit innovative solutions, governments must take care to ensure they do not overspend in what is a non-competitive process.

Given these risks, DTF and relevant agencies must rigorously assess MLPs against the guideline requirements to give confidence to the government and the community that successful proposals are genuinely unique and provide VFM.

1.2 The MLP assessment and approval process

DTF first issued guidelines for unsolicited proposals, now called MLPs, in February 2014. DTF's amendments to the guidelines later that year addressed our recommendation that proposals of more than $100 million be subject to HVHR requirements.

In February 2015, the government replaced the guidelines with the Market-led Proposals Interim Guideline. It updated this document in the Market-led Proposals Guideline November 2015. The current version of the guideline is the Market-led Proposals Guideline November 2017.

Current five-stage process

The current MLP guideline specifies the five-stage assessment and award process outlined in Figure 1A. A proposal must pass each step to proceed to the next.

Figure 1A

Current MLP five-stage assessment and award process

|

Stage |

Action |

|

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Preliminary assessment |

Assess sufficiency and relevance of information. Assess whether the proposal is within the scope of the guideline. |

|

2 |

Due diligence and strategic assessment |

Assess proposal against assessment criteria. If suitable to proceed, consider whether it should be through exclusive negotiation or a competitive tender process. |

|

3 |

Procurement preparation |

Agree with the proponent on:

Undertake further due diligence. |

|

4 |

Exclusive negotiation or limited competitive process |

Evaluate and benchmark a final offer for government consideration. Assess affordability, value for money, expected benefits, and scope. Recommend whether to award contract. |

|

5 |

Contract award |

Enter binding contractual arrangements. Agree governance structure and publish project summary and executed contract. |

Source: Market-led Proposals Guideline November 2017, Diagram 1: Market-led proposal assessment process, page 4.

This assessment process has been in place and broadly consistent since February 2015.

The process does not rule out competitive delivery. However, it allows for situations where an innovative idea or competitive advantage means awarding a contract to a private party without competition.

The guidelines emphasise that, wherever possible, a proposal should incorporate competitive downstream tendering to ensure VFM outcomes.

The government bases its decision on whether procurement should be through exclusive negotiation or a competitive process on advice from DTF and lead agencies.

1.3 Key assessment criteria for MLPs

The MLP guideline includes the government's key criteria for assessing proposals. Proposals must:

- have unique characteristics resulting in outcomes that are not likely to be obtained using standard competitive processes within acceptable time frames and therefore justify exclusive negotiations with government

- meet a service or project need that is aligned with government policy objectives

- represent VFM for Victorians

- have significant social, environmental, economic or financial benefits for Victorians

- be affordable in the context of budget priorities

- be commercial, feasible and capable of being delivered.

Proposals need to satisfy these criteria to proceed under the MLP guideline.

Uniqueness and VFM are critical criteria.

Unique characteristics

For a proposal to be considered outside of the usual competitive process, it must have 'unique characteristics'. Figure 1B shows how the approach to determining whether a proposal is unique has evolved in iterations of the MLP guideline.

Figure 1B

Evolution of uniqueness criterion in the MLP guideline

|

February 2014 |

February and November 2015 |

November 2017 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Preliminary assessment (Stage 1) |

◯ Assessed in Stage 2 |

⬤

Potential to demonstrate a level of uniqueness Minimum information requirements for a detailed description of the unique characteristics |

⬤

Potential to have unique characteristics resulting in outcomes not likely to be obtained using standard competitive processes, within acceptable time frames |

|

Key assessment criteria (to justify exclusive negotiation) (Stage 2) |

⬤

Proponent may have a unique idea or intellectual property, be in a unique position, or have ownership of strategic assets integral to delivery |

⬤

Government cannot reasonably engage another party to:

In assessing uniqueness, the government will consider whether:

|

⬤

Has present, verifiable and enforceable unique characteristics Provides value to government compared with alternatives Proponent is in a unique position to deliver the desired outcome to government Note: may be assessed holistically or have additional uniqueness test applied if uniqueness is still not determined |

Note: The dark blue circle represents more comprehensive assessment guidance, lighter blue circle represents limited assessment guidance, and uncoloured circle represents no assessment guidance.

Source: VAGO, based on DTF's MLP guideline.

Before November 2017, the MLP guideline required proponents to demonstrate uniqueness by the end of Stage 2 to justify further exclusive negotiations with the government.

Under the current MLP guideline, a proposal that may not meet all of the uniqueness characteristics specified in the guideline may still be assessed as unique when considered holistically. If a proposal is not assessed as unique at the end of Stage 2, it will only progress to Stage 3 if an additional uniqueness test has been undertaken and the government has approved progressing with a limited competitive process.

Value for money

VFM is a key assessment criterion under the MLP process, and therefore critical to a proposal's success. The MLP guideline indicates that VFM is informed by multiple factors, including the proposal's risk and the reasonableness of costs to government to achieve promised benefits.

DTF's guidance on how to determine whether a proposal represents VFM for Victorians has evolved over time, as shown in Figure 1C.

VFM is assessed in two parts: a quantitative assessment of the proposal and a qualitative assessment of the value of the proposal.

The quantitative assessment includes comparing the proposal's cost to a state benchmark for the proposal, either a public sector comparator or a realistic alternative. The qualitative assessment involves assessing the proposal as a whole, including benefits and any commercial principles underpinning the proposal, including risk allocation.

The current MLP guideline considers VFM at each of the first four MLP assessment stages in varying degrees of detail.

Figure 1C

Evolution of VFM criterion in MLP guideline

|

February 2014 |

February 2015 |

November 2015 |

November 2017 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Preliminary VFM Assessment (Stage 1) |

◯ | ⬤

Proposal is required to address expected VFM (but no specific assessment criteria). |

⬤

Assesses VFM as one of five key criteria. |

|

|

Assessment of potential VFM (Stage 2) |

⬤

Prescriptive guidance. Suggested steps. |

⬤

Assesses risk and reasonableness of costs to government. |

⬤

Assesses likelihood of affordability given required investment. |

⬤

Now informed by scope, time lines and risk allocation. |

|

VFM Qualitative Assessment (Stage 2) |

◯ | ⬤

Includes CBA and documentation of risks to achieving identified benefits. |

||

|

VFM Quantitative Assessment (Stage 2) |

◯ |

⬤ Now informed by scope, time lines and risk allocation. |

||

|

Consideration of VFM in assessing uniqueness (Stage 3) |

◯ | ⬤

Asks whether VFM is improved compared to other approaches. |

||

|

Process for determining VFM (Stage 3) |

◯ | ⬤

Only requires that the formal agreement includes the process for determining VFM. |

⬤

Public-sector comparator or realistic alternative may be developed. |

|

|

VFM Qualitative Assessment (Stage 4) |

◯ | ⬤

Assess proposal as a whole and individual value drivers. |

⬤

Document risks to achieving benefits identified in qualitative assessment. CBA included. |

|

|

VFM Quantitative Assessment (Stage 4) |

◯ | ⬤

Compare final proposal's cost to State Benchmark. |

⬤

Finalise comparator or realistic alternative estimate. |

|

Note: The dark blue circle represents more comprehensive assessment guidance, lighter blue circle represents limited assessment guidance, and uncoloured circle represents no assessment guidance.

Source: VAGO, based on DTF's MLP guideline.

1.4 MLP process governance and approvals

The MLP guideline specifies governance and approval arrangements for each stage of the assessment process. Figure 1D outlines the stakeholder responsibilities within these arrangements.

Figure 1D

Stakeholder responsibilities

Source: VAGO.

1.5 MLP process probity and disclosure

Each version of the MLP guideline includes a government commitment to uphold the highest levels of integrity and transparency in assessing proposals and specifies requirements for probity and disclosure.

The November 2017 MLP guideline enhanced disclosure and probity requirements to ensure the framework upholds this commitment. It:

- makes DTF responsible for coordinating disclosure and advising the Treasurer when information is disclosed

- requires that the proponent and the public sector specify probity requirements, including the plans put in place at each stage.

Figures 1E and 1F outline the disclosure and probity requirements of the MLP assessment process.

Figure 1E

Disclosure requirements during MLP assessment process

|

Stage/time |

Disclosure details |

Published on |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

At any time |

DTF reserves the right to disclose details of a proposal if a proponent has not complied with its probity requirements and the circumstances set out in the guideline*. |

Guideline does not specify |

|

2 |

During |

Where a proposal is subject to an additional uniqueness test, the desired outcomes and/or key elements the proposal seeks to deliver. |

Victorian Government Tenders website |

|

End |

Proposal including:

|

DTF website |

|

|

3 |

Start |

Stage 3 Probity Plan. |

DTF website |

|

End |

Detailed proposal description, covering:

|

DTF website |

|

|

4 |

Start |

Stage 4 Probity Plan. |

DTF website |

|

End |

Update of previously disclosed detailed proposal description. |

DTF website |

|

|

5 |

Within 60 days of close** |

|

DTF website Victorian Government Tenders website |

Note: *In the Guideline Appendix: Terms and Conditions.

** Within 60 days of contractual or financial close.

Source: VAGO, from DTF's MLP guideline.

Figure 1F

Probity requirements during MLP assessment process

|

Stage |

Proponent |

DTF |

Lead agency |

Government |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Submission |

Must declare any conflicts of interest. |

||||

|

1 |

Assesses proposal in accordance with DTF Probity Plan for Stage 1 Assessment. |

||||

|

2 |

Signs formal commitment at start of stage covering confidentiality, communication protocols and conflicts of interest. |

Assesses proposal in accordance with DTF Probity Plan for Stage 2 Assessment. Prepare Stage 3 Probity Plan. |

Approves Stage 3 Probity Plan. |

||

|

3 |

Must appoint a probity adviser for Stages 3 and 4 to advise and represent them on any probity issues that arise. Agrees Stage 4 Probity and Process Deed with lead department. |

Assess proposal in accordance with Stage 3 Probity Plan. Agree terms of Stage 3 Probity and Process Deed. Agrees Stage 4 Probity and Process Deed with proponent. |

Approves Stage 4 Probity and Process Deed if the proposal progresses to Stage 4. |

Interactions between the public sector and proponents are guided by the Stage 3 or Stage 4 Probity and Process Deed. This includes agreeing the process for any cost reimbursement. |

|

|

4 |

Exclusive negotiations to be based on Stage 4 Probity and Process Deed. Assess proposal in accordance with Stage 4 Probity Plan. |

Source: VAGO based on DTF's MLP guideline

1.6 MLP process application:three examples

This audit examined whether DTF and lead agencies assessed the following MLPs in accordance with the MLP guideline:

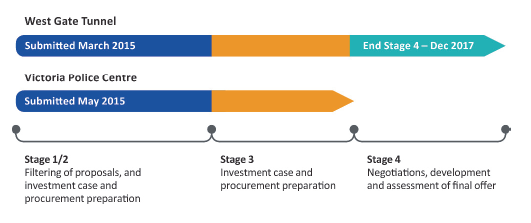

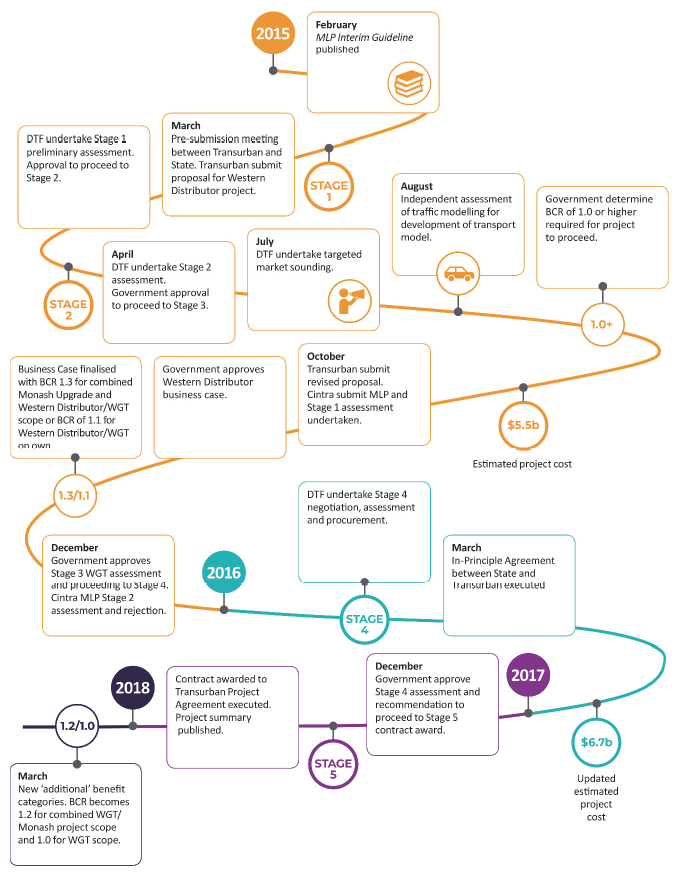

- WGT Project: Transurban submitted a proposal in March 2015, with a contract finalised in December 2017.

- VPC: Cbus/Australia Post submitted a proposal in May 2015, with a contract finalised in January 2017.

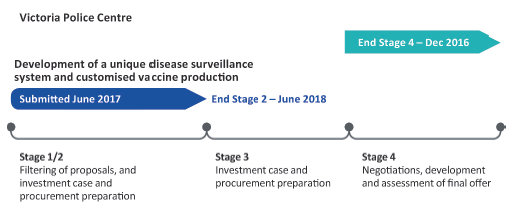

- Development of a unique disease surveillance system and production of disease prevention products for Victoria: proposal submitted in June 2017 and rejected in June 2018.

The audit focused on the application of the MLP process. This included examining alternative proposals received for both the WGT and VPC.

The audit did not examine delivery of the approved proposals.

Relevant guidelines

Figures 1G and 1H shows the MLP guideline versions that DTF and lead agencies used to assess the three proposals across the four assessment stages.

Figure 1G

MLP Interim Guideline (February 2015) proposals

Source: VAGO.

Figure 1H

MLP Guideline (November 2015) proposals

Source: VAGO.

1.7 Gateway Review and HVHR process

The Gateway Review and the HVHR processes are project assurance mechanisms overseen by DTF to review and improve project selection, management, delivery and outcomes.

The Gateway Review Process involves short, intensive reviews by a team of reviewers independent from the project at six critical points or 'gates' in the project life cycle. The reviews check that projects are on track before continuing to their next stage and are intended to support project owners.

The Gateway Review Process has been mandatory for all high risk projects since 2003, and for projects that are considered high risk or high value (over $100 million) since 2011. The onus has been on departments and agencies to opt in to the Gateway Review Process.

The government's HVHR project assurance framework was introduced in 2010. DTF performs HVHR reviews for the Treasurer. The HVHR process aims to achieve greater rigour in investment development and oversight, increasing the likelihood of timely project delivery and benefits realisation for Victorians.

A project is classified as HVHR if it is a budget-funded project that is:

- considered high risk using DTF's risk assessment tool, the Project Profile Model

- considered medium risk using the Project Profile Model tool and has a total estimated investment of between $100 million and $250million

- considered low risk using the Project Profile Model tool but has a total estimated investment over $250 million, or

- identified by the government as warranting the rigour applied to HVHR investments.

The HVHR has linked gateway reviews to key project approval points and mandated that projects costing over $100 million and/or assessed as high risk must be reviewed at all six gates.

1.8 Prior reviews relevant to this audit

Applying the High Value High Risk Process to Unsolicited Proposals

In our 2015 audit we found that, in some instances, when DTF applied the HVHR process to unsolicited proposals there was inadequate:

- assurance about the deliverability of the proposal's benefits

- assessment of the alternative funding options

- engagement with stakeholders about the likely impacts.

East West Link Project

This audit, also published in 2015, found that the business case for the East West Link project did not provide a sound basis for the government's decision to commit to the investment.

1.9 Who this audit examined

This audit examined whether DTF and lead agencies assessed the selected MLPs in accordance with government requirements.

Department of Treasury and Finance

DTF is responsible for the MLP guideline and process, and:

- receives all proposals and does not progress any until the Deputy Secretary, Commercial Division or the Treasurer approves the Stage 1 assessment

- leads the assessment of proposals at Stage 1 and Stage 2 of the guideline in consultation with relevant departments

- is responsible for chairing the IDC to oversee assessment of proposals

- provides support when another department or agency leads an assessment, by contributing to the assessment as required (this varies depending on the nature of the proposal) and providing advice to the lead department or agency regarding application of the MLP Guideline requirements

- briefs the Treasurer throughout the assessment process.

DTF is required to consult with relevant portfolio agencies and IDC members to undertake the strategic assessment of all proposals. This consultation feeds into the recommendations provided to government on whether to pursue the proposal and, if so, how it will be procured.

Lead agencies

During Stages 3, 4 and 5, the government-approved lead department, which can also be DTF, undertakes the MLP assessment. When another department or agency leads an assessment, DTF provides support. DTF and relevant departments and agencies brief the MLP IDC throughout the assessment process

The former Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources

DEDJTR (now DoT and DJPR) was represented on the IDC and involved in assessing the MLPs for the WGT project and the development of a unique disease surveillance system.

The government-operated Pig Services Centre at Epsom, near Bendigo, then part of DEDJTR's Agriculture Policy branch (now within DJPR) was involved in assessment of the unique disease surveillance system.

Department of Premier and Cabinet

DPC is represented on the IDC and was part of the steering committees established to oversee the assessment of the WGT project.

DPC also engaged an independent review panel to examine the Stage 2 assessment of the WGT proposal and the business case for the WGT project.

West Gate Tunnel Project

West Gate Tunnel Project is a project office within the Major Transport Infrastructure Authority in DoT. It is responsible for the delivery of the WGT project. It was previously known as the Western Distributor Authority and more recently the West Gate Tunnel Authority.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police provided input into the Stages 1 and 2 assessments of the VPC proposal and led negotiations with the proponents from Stage 3 onwards. Victoria Police also developed the Stages 3 and 4 assessment reports on the VPC in consultation with DTF.

1.10 What this audit examined and how

This audit analysed whether DTF and lead agencies assessed MLPs in accordance with government requirements. We examined whether DTF and lead agencies:

- complied with the MLP guidance and other relevant process and review requirements when assessing selected proposals

- applied the MLP process rigorously and comprehensively to provide assurance on the merit of selected proposals and a sound basis for government decisions on whether and how these proposals should proceed.

We also assessed whether DTF and lead agencies:

- met the due diligence, probity, governance and approval, consultation and public disclosure requirements in the MLP guideline

- complied with other applicable oversight, assurance and review mechanisms such as the HVHR and Gateway Project Assurance frameworks.

Our original audit scope also included the development of a unique disease surveillance system and production of disease prevention products for Victoria.

The MLP for this was submitted in June 2017 and rejected in June 2018. We did not evaluate this in depth because our initial inquiries indicated there were no significant issues with the MLP process.

We conducted our audit in accordance with the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements relate to the assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $1 115 000.

1.11 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the uniqueness assessment for the WGT MLP and the business case, including options assessment and cost benefit analysis.

- Part 3 examines the VFM assessment for the WGT MLP.

- Part 4 examines the assessment of the VPC MLP.

- Part 5 examines the assessment of alternative proposals for the VPC.

2 West Gate Tunnel project: uniqueness, options and benefits

Source: http://westgatetunnelproject.vic.gov.au.

After discussions with the government in late 2014 and early 2015, Transurban submitted its proposal for what became known as the WGT project in March 2015. DTF and lead agencies assessed the proposal through all five stages of the MLP process between March 2015 and December 2017 using the February 2015 version of the MLP guideline.

DTF and the relevant agencies assessed Transurban's WGT proposal as meeting the key MLP assessment criteria. DTF advised the government in December 2017 that Transurban's final offer was unique and represented good VFM, meaning it satisfied the Stage 4 MLP guideline criteria to proceed to Stage 5—awarding a contract.

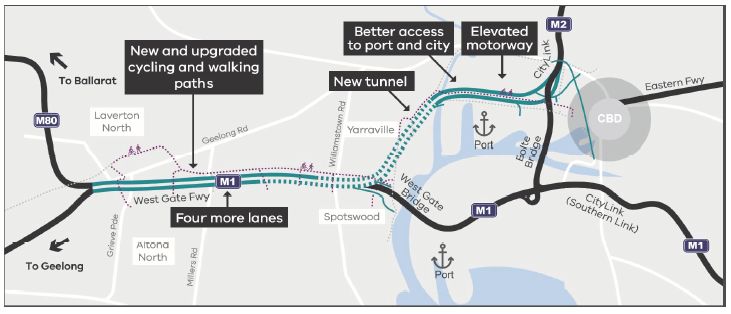

The government signed a public-private partnership (PPP) contract with Transurban on 11 December 2017. The WGT will give road users an alternative to the West Gate Bridge. The WGT component of the project involves:

- the construction of a road tunnel

- widening of the West Gate Freeway

- an elevated motorway that will link the West Gate Freeway to the CityLink tollway and the Port of Melbourne.

Under the contract, Transurban must design, partially finance and construct the WGT, then operate, toll and maintain it until January 2045, when it will transfer responsibility back to the state. The contract also requires Transurban to manage Stage 1 of the Monash Freeway upgrade and deliver improvement works at Webb Dock, a port facility at Fishermans Bend.

In this Part, we examine whether DTF and the former DEDJTR (now DoT) assessed the MLP for the WGT in accordance with relevant MLP guideline requirements concerning uniqueness. We also examine the quality of the business case in justifying project scope, assessing options and estimating benefits compared to costs.

2.1 Conclusion

DTF and lead agencies advised the government that Transurban's proposal met the requirements for uniqueness primarily based on Transurban's capacity to access, escalate and extend toll revenues on its existing CityLink concession.

DTF assessed the CityLink escalation and extension funding source as unique because no party other than Transurban could access revenue from increasing tolls on CityLink prior to 2035, and no other party could access revenue from an extended concession until after 2035. Identifying the CityLink escalation funding source as unique was consistent with the MLP guideline. The uniqueness of the extension funding is less clear, as the possibility for the state or another provider to take up this funding source existed.

The MLP guideline is silent on the level of materiality unique characteristics should represent. Together, these funding sources made up almost 50 per cent of the total funding sources identified and estimated by the state for the project.

The uniqueness assessment and project business case lacked a comprehensive analysis of the costs and benefits of adopting alternate funding options for delivering the project. DTF's advice to the government would have been more comprehensive if it had included such analysis.

Since the community will pay for the WGT project whichever funding source is adopted, we question whether funding should have been considered the defining unique characteristic to exclude a competitive procurement process.

In addition, the business case did not adequately justify the inclusion of the Monash Freeway upgrade in the project scope. The inclusion of this scope element improved the project BCR. There was also a lack of transparency in the CBA that limited assurance that the risks of overstating benefits had been addressed.

2.2 Uniqueness

Assessment

The February 2015 MLP Interim Guideline defined unique characteristics as including proponents being in a unique position or owning strategic assets to deliver desired outcomes, including having:

- rights under an existing contract

- ownership of land, technology or software, or

- exclusive access to, or control over, strategic assets integral to delivering the proposal or improved outcomes for the government.

In December 2015, DTF advised the government that Transurban's proposal satisfied the MLP guideline uniqueness test and provided material benefits to the state that could not be achieved through a standard competitive process.

DTF assessed the proposal as unique based on Transurban's capacity to access toll revenue from:

- its existing concession on the Melbourne CityLink

- escalated and extended CityLink tolls.

That is, the assessment of uniqueness was based primarily on Transurban's funding model for the project. The Transurban proposal relied on revenue from four sources—an upfront payment from the government, tolling revenue on the new WGT road, additional increases to tolls from its existing CityLink concession and an extension of that concession for another 10 years. These funding sources were contingent on government actions and parliamentary support.

Adequacy of the assessment

Our examination of the uniqueness assessment process identified three key issues:

- The assessment was not balanced by examination of other possible providers and funding sources.

- The MLP guideline does not specify a threshold or approach to assessing the materiality of the uniqueness.

- The MLP guideline does not specifically deal with primary and secondary unique characteristics.

In addition, not all funding sources cited were uniquely deliverable by Transurban and there was uncertainty around these funding sources when awarding the WGT proposal contract. Transurban could not have secured or delivered the funding sources identified by DTF as unique without direct government policy decisions and parliamentary support.

Funding sources and balance of uniqueness assessment

Transurban's position as the operator of CityLink is certainly unique as it is the only entity that can access CityLink tolling and escalation revenue.

|

Transurban … |

However … |

|

Was the only party with the right to operate and toll the existing CityLink to 2035 |

Transurban did not have any existing rights or capacity under the Concession Deed to:

|

|

Included access to the CityLink toll revenue stream beyond the 2035 expiry of its existing concession in its proposal |

The DTF advice to government at Stage 4 recommending that it sign the contract with Transurban made it clear that access to this funding source was not certain, as it relied on parliamentary support. |

Source: VAGO.

DTF's advice to government on the Stage 4 assessment correctly noted that:

- if the government could not secure the relevant legislative changes and parliamentary support to deliver the funding sources, the primary unique characteristic in the Transurban proposal would be eliminated

- other parties could not access the CityLink toll revenue streams without government support

- Transurban also required government support to secure revenue from its CityLink toll escalation and extension

- these funding sources were not certain because they relied on the actions of a future parliament.

DTF's assessment and subsequent advice to the government focused on funding sources and advised that the CityLink escalation and extension funding source was uniquely accessible by Transurban.

The uniqueness assessment would have been more comprehensive if DTF had also:

- demonstrated why the proposed funding sources provided more beneficial outcomes than other options available, by valuing the relative benefits of Transurban's ability to access this funding compared to other market participants

- examined whether other entities could offer the same project outcomes and benefits in a similar time frame. To do so would have been more consistent with the MLP guideline.

While Transurban's access to CityLink escalation revenue was unique, it is less clear that extension revenue is unique. The right to operate the CityLink concession after Transurban's concession deed expired in 2035 could have been granted to a state-owned tolling company or a different private sector operator.

DTF rightly identified that because this revenue cannot begin flowing until 2035, parties other than Transurban may face challenges in raising project finance tied to this funding source on a VFM basis. However, DTF's assessments of the uniqueness of the Transurban proposal did not include any substantive analysis of the option to grant another private operator access to the CityLink extension as a source of revenue.

Materiality of uniqueness characteristics

The MLP February 2015 guideline specifies that:

'It is not sufficient to only demonstrate the presence of unique characteristics in a proposal. It must also be demonstrated that these characteristics provide value for money and other benefits for government that could not be achieved through a standard competitive process outside of the guideline within acceptable time frames'.

It is appropriate to estimate the size of any claimed unique benefits of a proposal. However, the guideline does not specify an approach or threshold for assessing how material uniqueness benefits need to be to support exclusive negotiations and is unclear about whether benefits should be measured against a state benchmark or other private providers.

The CityLink escalation funding source made up between 14 and 18 per cent of the total funding sources identified and estimated by the state and Transurban for the project. DTF advised us that this was sufficiently material to justify proceeding as an MLP.

It is less clear whether the 10-year extension CityLink concession the government gave to Transurban was unique. This made up around 31 per cent of the total funding sources the state identified and estimated for the Transurban project.

Primary and secondary uniqueness factors

As shown in Figure 2A, DTF's Stage 4 assessment of the Transurban proposal introduced a distinction between two levels of uniqueness.

Figure 2A

Levels of uniqueness in the Stage 4 assessment

|

Level of uniqueness |

Type of factor |

|---|---|

|

Primary |

Funding sources |

|

Secondary |

Related to potential for Transurban to realise operational synergies and economies of scale from:

|

Source: VAGO.

The MLP guideline does not refer to primary and secondary uniqueness factors. It is unclear how DTF weighed the significance of the primary and secondary factors and how each factor impacted the assessment.

DTF updated the MLP guideline in November 2017 to refer to a holistic assessment of uniqueness, including consideration of other factors that may be considered material to demonstrate a unique proposal. DTF can further enhance the guideline by providing additional information and guidance about assessing the materiality of unique characteristics including primary and secondary uniqueness factors.

2.3 Service need and benefits

Business case

The government approved the outcome of the Stage 2 assessment of Transurban's proposal in April 2015. Parallel to the Stage 3 assessment, it asked DEDJTR to develop a business case, with support from DTF, to examine the project's merits, irrespective of the delivery method and potential involvement of Transurban.

A business case should clearly establish service need and project scope, examine solution options and demonstrate project benefits.

The DEDJTR business case for the project was provided to the government in October 2015 and:

- did not reasonably explain the inclusion of the Monash Freeway widening works in the WGT project scope, which improved the BCR

- showed a marginal value proposition for the WGT project on its own but had limited transparency regarding the sensitivity of the BCR for the WGT project scope element

- did not examine a range of alternative project options in sufficient depth

- did not have a fully transparent CBA, meaning the user of the advice could not be assured that benefits had not been overstated.

Inclusion of Monash Freeway upgrade in project scope

The justification for including the Monash Freeway widening works in the WGT project scope lacked a convincing rationale and was inconsistent with DTF's guidelines on separate business cases for multiple related projects and the findings of independent reviews.

Business case scope

The government's commitment in late 2014 to construct a West Gate Distributor project did not include any works on the Monash Freeway east of Toorak Road. Similarly, the project scope in Transurban's initial proposal in March 2015 did not include these works.

DTF's Stage 1 and Stage 2 assessments of Transurban's proposal and related advice to the government in April 2015 did not refer to Monash Freeway upgrade works as part of the project scope for the state's reference project or in any other context.

Given this, it is reasonable that the project scope for the business case would be largely consistent with the scope of Transurban's proposal.

However, DTF's advice to the government in August 2015 indicated that the state's base scope for the project included Monash Freeway upgrade works. DTF indicated that these works could deliver additional user benefits along the M1 corridor, but did not provide a clear rationale for combining this scope item with the Transurban proposal.

Figure 2B shows the geographic and preferred investment scopes outlined in the October 2015 Western Distributor business case. This proposed investment scope covered a wide geographic area and comprised several distinct key project scope elements.

Figure 2B

October 2015 Western Distributor business case scope

|

Geographic Scope |

Preferred Investment Scope |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: VAGO from Western Distributor Business Case, October 2015.

The works proposed as part of the Monash Freeway upgrade were:

- around 15 kilometres away from the core WGT project scope at their closest point (Toorak Road)

- over 60 kms away at the farthest point.

These works and related benefits were unrelated to the WGT works.

The inclusion of the Monash Freeway upgrade in the Western Distributor business case was not consistent with DTF's Investment Lifecycle and HVHR guidelines. These guidelines allow for a single master plan, or program business case covering outcome-focused investments that bring together multiple projects under a single coordinating structure. While not mandatory, the guidelines state that agencies should prepare separate business cases for the major projects that are part of the master plan or program.

Both the peer reviewer appointed by DEDJTR and the Independent Review Panel (IRP), appointed by DPC to review the business case, pointed out the need to better justify the inclusion of the Monash Freeway upgrade works in the business case.

Independent Review Panel findings

The IRP review:

- identified that the Monash Freeway scope element contributed a significant proportion of overall project benefits

- did not agree that the two projects should be combined into a single business case

- recommended separate business cases for the WGT and Monash Freeway upgrade because it saw very limited overlap between the problems and the benefits.

DTF did not accept this IRP recommendation, and was transparent about this in the relevant advice to the government. However, DTF's advice that this recommendation could be addressed by simply strengthening the justification for presenting two separate works packages in a single business case did not fully address the issues raised by the IRP. DTF provided the government with an option to separate the business cases, noting that this option would delay the finalisation of the business case. The government approved the retention of a single business case approach in October 2015.

The IRP also recommended that the business case present the results of the CBA for both the WGT and the Monash Freeway upgrade separately. DTF asked the government to determine the response to this recommendation. The government agreed that the final business case show separate BCR results for the WGT and Monash Freeway upgrade and a BCR for the combined project scope.

Transparency of BCR analysis

In August 2015, the government determined that the WGT project would not proceed unless the business case demonstrated that it had a positive BCR, meaning 1.0 or above.

The CBA in the business case provided to the government in October 2015 used a discount rate of 7 per cent and showed a marginal value proposition for the WGT project and a strong value proposition for the Monash Freeway upgrades. Figure 2C shows these BCRs.

Figure 2C

Final business case BCRs

|

Project |

BCR |

|---|---|

|

Monash Freeway upgrade and the WGT (combined project) |

1.3 |

|

Monash Freeway upgrade (solo project) |

4.2 |

|

WGT (solo project) |

1.1 |

Source: VAGO, from Western Distributor Business Case, October 2015.

|

A sensitivity analysis shows how the viability of a project changes if some variables deviate from expected values. The analysis is useful when projects involve uncertainty as it can demonstrate whether the preferred solution option would be still worthwhile pursuing if key assumptions were incorrect. |

The business case only included sensitivity analysis results for the combined project scope.

The sensitivity analysis showed the impacts of applying a higher and lower discount rate and different assumptions about project costs. Applying a discount rate of 10 per cent to reflect greater uncertainty or project risk reduced the BCR for the combined project scope to 0.8. This meant that the present value for project costs exceeded the present value of project benefits. Applying a discount rate of 4 per cent increased the BCR for the combined project scope to 2.3.