Public Hospitals: Results of the 2013–14 Audits

Overview

This report covers the results of the financial audits of 110 entities within the public hospital sector, comprising 87 public hospitals and the 23 associated entities. It informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the 2013–14 financial audits and complements the assurance provided through audit opinions included in the entities’ annual reports. The report also looks at public hospital financial results, financial sustainability and targeted areas of internal controls related to internal audit and asset maintenance functions.

Parliament can have confidence in the 2013–14 financial statements of the 87 public hospitals, and their 23 associated entities, as all were given unmodified audit opinions.

Public hospitals continue to face challenges in delivering quality health services to the public due to increasing demand, an ageing population, and limited funding streams. Our overall assessment of public hospitals at 30 June 2014 indicated that many had significant financial sustainability risks that need addressing.

These financial sustainability risks have been highlighted in previous reports from this office on public hospitals, which have consistently shown that the current funding model has resulted in a clear mismatch between public hospital boards' responsibilities for the sustainable management and provision of services, and the boards' ability to control the funding they receive to enable them to do this.

Public Hospitals: Results of the 2013–14 Audits: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2015

PP No 7, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on Public Hospitals: Results of the 2013–14 Audits.

This report summarises the results of the financial audits of 87 Victorian public hospitals and 23 associated entities at 30 June 2014.

It informs Parliament about significant issues identified during our audits and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the entities' annual reports.

The report highlights the sector's financial sustainability risks and financial results. It also found that public hospitals can improve their asset management and internal audit arrangements.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

25 February 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Charlotte Jeffries—Sector Director Helen Grube—Team Leader Peter Georgiou, Janelle Birch, Patricia Duong, Siu Fa Lau and Anh Ha—Team members Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Craig Burke |

Public hospitals are responsible for the management and delivery of essential public health services across the metropolitan, regional and rural sectors of the state. Parliament can have confidence in the 2013–14 financial statements of the 87 public hospitals, and their 23 associated entities, as all were given unmodified audit opinions. It is pleasing to note that financial reporting by public hospitals was generally more timely and accurate in 2013–14 than the prior year.

However, public hospital management teams had not resolved 30 per cent of the 358 internal control weaknesses identified and reported to their boards by my audit teams during the 2012–13 audits, or earlier. This lack of timely resolution means that the control frameworks in place at these entities are not as effective as they should be. Management should seek to address all issues raised by my office on a timely basis.

Public hospitals continue to face challenges in delivering quality health services to the public due to increasing demand, an ageing population, and limited funding streams. To be financially sustainable, hospitals need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure requirements as they fall due, and to maintain and replace their assets as required.

Our assessment of public hospitals at 30 June 2014 indicated that many had significant financial sustainability risks. These risks in part arise from the tight cash position in which many public hospitals operate. This is illustrated by 12 public hospitals only holding enough cash at 30 June 2014 to fund their operations for seven days or less. If these hospitals did not receive a grant payment within this period they would be required to access other funding sources, which include seeking a recallable grant from the department.

The financial sustainability risks of public hospitals have been highlighted in previous reports from this office. These reports have consistently shown that the current funding model has resulted in a mismatch between public hospital boards' responsibilities for the sustainable management and provision of health services—and the boards' limited ability to control the funding they receive, particularly from the department, to enable them to do this. This mismatch needs to be addressed as it blurs accountability for the financial performance of public hospitals.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

February 2015

Audit Summary

This report presents the outcomes and observations from the financial audits of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities for the financial year ended 30 June 2014. These entities are responsible for the delivery of public health services across metropolitan, regional and rural Victoria.

The report summarises the results of the financial audits of the 110 entities and provides an analysis of the timeliness and accuracy of financial reporting by these entities. It also assesses the financial sustainability risks that the 110 entities face, and informs Parliament about issues identified during our review of internal audit and asset maintenance functions at the 87 public hospitals.

Over the 2013–14 financial year, the 87 public hospitals were collectively responsible for $12.6 billion of expenditure in delivering public health care services, and delivered an overall, but marginal, surplus for the sector of $235 million.

Conclusions

Parliament can have confidence in the financial reports of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities, as all financial reports were given unmodified audit opinions. The financial reports prepared by public hospitals and their associated entities were also generally timely and accurate.

However, there are still concerns regarding the financial sustainability risks of hospitals, with 32 hospitals—including some major metropolitan hospitals—requiring a letter of financial support from the former Department of Health, in order to be able to report as a going concern as at 30 June 2014. Further, 12 public hospitals held cash at 30 June 2014 that could only fund seven or less days of operating activity.

The current funding model has resulted in a mismatch between public hospital boards' responsibilities for the sustainable management and provision of health services; and the boards' limited ability to control the funding they receive, particularly from the department, to enable them to do this.

Seventy per cent of public hospitals had a poor capital replacement risk result as at 30 June 2014. This means that many hospitals, particularly in rural areas, are not renewing or replacing fixed assets at the pace at which they are consuming them. This means that services may be at risk in the future due to assets becoming obsolete.

Findings

Quality of reporting

Clear opinions were issued for all of the financial reports of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities for the 2013–14 financial year. All 110 entities met their legislative reporting time frames, with public hospitals finalising their statements within an average of 7.3 weeks. This was an improvement of two weeks compared to the 30 June 2013 reporting period, due to efforts by management to complete the required work within the shortened timetable issued by the Department of Treasury and Finance.

The improvement in the timeliness of reporting was complemented by an improvement in the accuracy of the draft statements provided to audit, with only 51 material adjustments arising across the 110 entities, compared to 81 in the prior year. All material errors were adjusted prior to the audit opinion being signed.

Common reasons for the adjustments included errors in disclosures relating to the new Australian Accounting Standard AASB13 Fair Value Disclosures, and the updated Australian Accounting Standard AASB119 Employee Benefits.

General internal controls

Internal controls at public hospitals and associated entities were adequate for maintaining the reliability of external financial reporting.

Where weaknesses in internal controls are identified through our audits, these are reported to the board, audit committee and management through formal management letters. Across the 110 entities, however, a number of common weaknesses were identified. These included the need to improve the timely review of key reconciliations, and the need to ensure that there is always appropriate authorisation of supplier payments.

As part of our audit process, we followed up issues reported in our prior year management letters to confirm that management had sought to mitigate the risks regarding the control weaknesses identified. In our 2012–13 and earlier management letters, 358 items were raised across the 87 public hospitals. Of these, 106 items (30 per cent) had not been resolved by the time of our 2013–14 audit visit.

Financial sustainability risks

The 110 entities covered in this report are responsible for managing their finances so that they can deliver quality health care services to the state, while maintaining and renewing their fixed assets. To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure requirements as they fall due.

This is particularly challenging as the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities are funded through a combination of government and other revenue. Over the 2013–14 financial year, these entities were collectively responsible for $12.6 billion of expenditure in delivering public health care services, and delivered a surplus for the sector of $235 million. Our overall financial sustainability assessment for the sector at 30 June 2014 is 'medium', which is consistent with our assessment last year. This indicates that there are concerns regarding the financial sustainability risks of many public hospitals.

Despite the overall financial results achieved by the sector in 2013–14, 32 public hospitals (28 in 2012–13) showed signs of financial stress, with a material uncertainty about their ability to continue as a going concern for financial reporting purposes. This means they are considered to be at risk of not being able to meet all their financial obligations over the next 12 months.

To mitigate this risk, the former Department of Health provided letters of financial support to these 32 public hospitals. The letters provide an undertaking by the department to provide adequate cash flows to the named hospital to enable them to meet their current and future financial obligations up to September 2015, if required. While this does not provide additional funding, it does mean that potential assistance is available if the public hospital faces financial difficulties.

Another concern is the tight cash environment in which public hospitals operate, with 12 public hospitals having cash at 30 June 2014 that could only fund seven or less days of operating activity. While this is an improvement on the prior year result of 23 public hospitals being in this position, it means that public hospitals are still at a significant risk of not being able to fund operating activities. Further, if these hospitals did not receive a grant payment during that 7 day period, they would be required to access other funding sources, which include seeking a recallable grant from the department.

In particular, we noted that 70 per cent of public hospitals have a poor capital replacement risk result. This means that many hospitals, particularly in rural areas, are not renewing fixed assets as they use them—as measured through depreciation. Where this is the case, public hospitals need to work with the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure that the quality of these assets—including buildings and medical equipment—does not degenerate to a point where the provision of services is put at risk.

As sector-wide asset revaluations occur every five years—and occurred in 2013–14—we expect an increase to the depreciation costs that will need to be met by public hospitals at 30 June 2015. The public hospitals' funding model does not progressively provide funding to public hospitals to match the depreciation of their assets.

The current funding model has resulted in a mismatch between public hospital boards' responsibilities for the sustainable management and provision of health services; and the boards' limited ability to control the funding they receive, particularly from the department, to enable them to do this.

Internal audit

Internal audit is a key mechanism available to the board of a public hospital to support the discharge of its governance and oversight responsibilities. During 2013–14, public hospitals collectively spent $4 million on their internal audit functions, this represented 0.03 per cent of overall expenditure in the sector. We reviewed the operations of internal audit in public hospitals during 2013–14.

Two public hospitals do not have an internal audit function—this is a breach of the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994, and a significant shortcoming in internal control.

Of the remaining 85 public hospitals, the internal audit functions generally operate effectively and are able to provide independent, objective advice and assurance to audit committees, boards and management.

However, some areas for improvement were noted. In particular, public hospitals need to ensure that they have a policy to mitigate any potential or actual conflicts of interest that may arise, which could impact the independence of internal auditors. This policy guidance could be provided through the implementation of better practice internal audit charters.

Public hospitals should also work with their internal auditors to set audit plans that assist in providing assurance regarding all key risks that the entity faces. Our review noted that while detailed and approved audit plans were in place at many public hospitals, they did not align well with the risk registers of these entities. This means internal audit may be less effective at highlighting potential control weaknesses or poor processes in those areas of greatest risk.

The following key business activities have not been reviewed by internal audit across all public hospitals over the last three years:

- controls over cash management not reviewed at 34 public hospitals

- data security not reviewed at 34 public hospitals

- data quality not reviewed at 37 public hospitals

- controls over asset management not reviewed at 44 public hospitals.

Public hospital boards should ensure they have adequate assurance over the control frameworks in these areas.

Asset maintenance

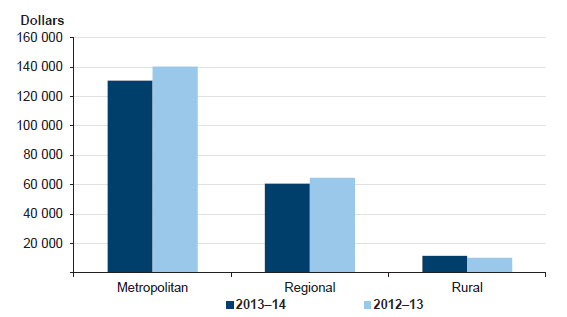

As at 30 June 2014, public hospitals operated $11.9 billion of assets, which require ongoing maintenance. In 2013–14, public hospitals spent $232 million maintaining these assets ($212 million in 2012–13).

Overall, we found that public hospitals can make improvements to their asset maintenance strategies, procedures and oversight to enable them to make better informed decisions regarding the level and type of asset maintenance required.

We found that 48 public hospitals did not have a policy or strategy in place that addressed asset maintenance. Of these 48 public hospitals, the majority do not have regular or detailed internal reporting that addresses the adequacy of maintenance spending, risk management, funding plans or life cycle maintenance and costing.

Rural hospitals spend a significantly smaller proportion of their net asset base on asset maintenance, compared to the larger regional and metropolitan hospitals. Inadequate maintenance of assets means a public hospital is at risk of not being able to efficiently provide services.

Public hospitals need to implement adequate asset management policies to provide a framework for asset maintenance decisions, and should also undertake comprehensive asset condition assessments to fully inform asset maintenance plans.

Recommendations

That public hospital boards and management:

- review their financial reporting processes to address the better practice report preparation elements, including the timely preparation of shell financial statements

- address all issues raised in audit management letters on a timely basis, including ongoing concerns regarding the need to improve controls around key account reconciliations, the authorisation of supplier payments, and the regular review of financial and information technology policies

- through audit committees, implement appropriate monitoring mechanisms to ensure audit findings are resolved by management on a timely basis

- maintain good cash management processes to ensure that they are able to meet their financial obligations as they fall due, particularly for those public hospitals assessed as having a high liquidity risk

- work with the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure they are able to renew ageing assets as required to prevent any loss of services provided to the public.

That Dunmunkle Health Service and Casterton Memorial Hospital:

- establish and maintain an internal audit function.

That public hospital boards and management:

- have in place stand-alone internal audit charters that provide a clear framework for the selection, operation and oversight of the internal audit function.

- establish a process for the identification, communication, assessment and mitigation of conflicts of interest between internal audit and the public hospital

- work with their internal audit function to develop and implement a three-year audit plan that is approved by the audit committee, and which aligns with the risks identified in the hospital's risk register

- review their internal audit plan to ensure that the internal audit function is providing the level of assurance required

- undertake annual performance reviews of the internal audit function to ensure it continues to operate in line with the internal audit charter

- implement better practice asset management strategies to provide a framework for asset maintenance decisions

- undertake comprehensive asset condition assessments to enable individual asset maintenance plans to be created and actioned

- maintain comprehensive and appropriate information regarding asset maintenance requirements to assist in strategic asset management planning.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Health and Human Services and named agencies with a request for submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Public hospitals provide a range of services across metropolitan, regional and rural areas. Metropolitan and regional public hospitals typically provide acute health services, as well as a mix of mental health, sub-acute, community health services and aged care programs. Rural public hospitals generally offer a higher proportion of aged care and community health services.

This report summarises the results of the financial audits of 110 entities, comprising 87 public hospitals and their 23 associated entities. It is one of a suite of Parliamentary reports on the results of the 2013–14 financial audits conducted by VAGO. The full list of reports can be found in Appendix A of this report.

A breakdown of the 110 entities commented on in this report is set out in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Public hospitals and associated entities

|

Hospital category |

2014 |

2013 |

|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan | ||

|

Public hospitals |

18 |

18 |

|

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

15 |

15 |

|

Other associated entities(a) |

2 |

2 |

|

Subtotal |

35 |

35 |

| Regional | ||

|

Public hospitals |

15 |

15 |

|

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

0 |

2 |

|

Subtotal |

15 |

17 |

| Rural | ||

|

Public hospitals |

54 |

54 |

|

Entities controlled by public hospitals |

5 |

5 |

|

Other associated entities(a) |

1 |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

60 |

60 |

|

Total |

110 |

112 |

(a) Other associated entities are not directly controlled by a public hospital and generally comprise joint ventures or stand-alone associated not-for-profit entities, such as hospital foundations.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The reduction of two entities is due to the operations of the Echuca Trust and the Echuca Foundation being subsumed into Echuca Regional Health. Appendix B contains a list of the entities audited by VAGO.

1.2 Structure of this report

This report informs Parliament about the findings arising from the audits of Victorian public hospitals, and adds to the assurance provided through audit opinions on the financial statements included in the respective entities' annual reports.

The structure of this report and details covered in each Part are set out in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Report structure

|

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Part 2: Quality of reporting |

Covers the results of the audits of the 2013–14 financial reports of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities. It comments on the timeliness and quality of financial reporting against better practice. It also provides the results of our assessment of certain general internal controls at these entities. |

|

Part 3: Financial results |

Summarises and analyses the financial results of the 87 public hospitals, including financial performance for 2013–14. It also provides insight into the financial sustainability risks of the 87 public hospitals, based on trends in financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. |

|

Part 4: Internal audit |

Assesses the internal audit function in each of the 87 public hospitals against a better practice framework. |

|

Part 5: Asset maintenance |

Assesses the policies, management practices, and governance and oversight arrangements in place at the 87 public hospitals against better practice. |

1.3 Audit of financial reports

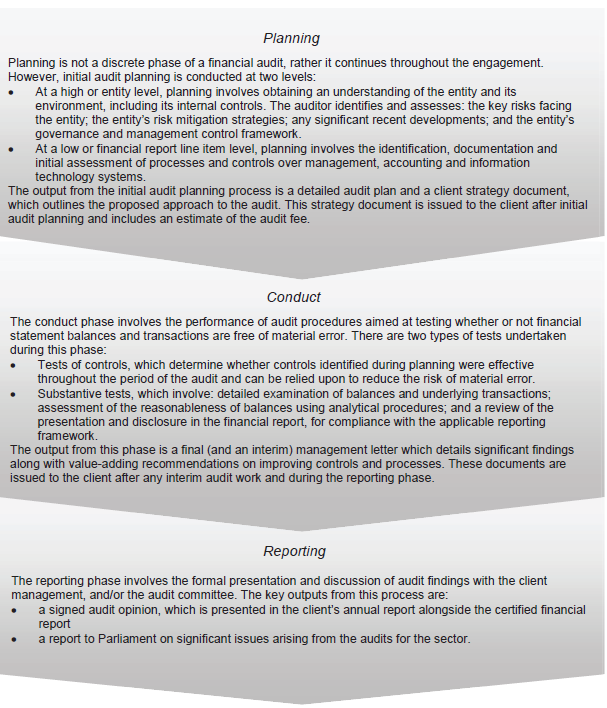

An annual financial audit has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether the financial report is presented fairly in accordance with the relevant financial reporting framework

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A(2) of the Audit Act 1994.

The financial audit framework applied in the conduct of the audits is set out in Appendix C.

1.3.1 Audit of internal controls relevant to the preparation of the financial report

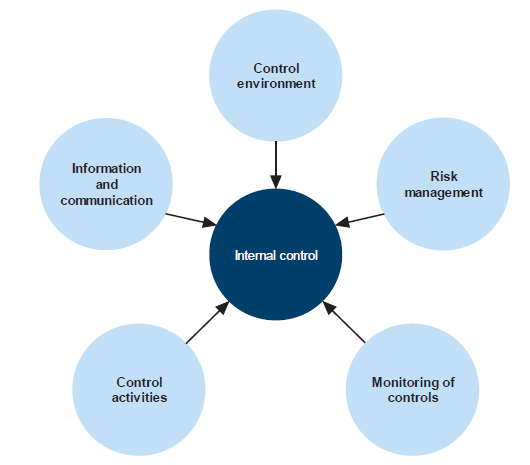

Integral to the annual financial audit is an assessment of the adequacy of the internal control framework, and the governance processes related to an entity's financial reporting. In making this assessment, consideration is given to the internal controls relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial report, but this assessment is not used for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control.

Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely internal and external reporting.

An explanation of the internal control framework, and its main components, are set out in Appendix C. An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework.

Internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a modified audit opinion because often an entity will have compensating controls in place that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report. Alternatively, additional audit procedures will also be conducted to mitigate any risks to the financial report identified as a result of the weakness.

Weaknesses in internal controls found during the audit of an entity are reported to its board, chief executive officer and audit committee in a management letter.

Our reports to Parliament raise systemic or common weaknesses identified during our assessments of internal controls over financial reporting, across a sector.

1.4 Public hospitals' funding framework

Prior to the 2012–13 financial year, Commonwealth grants for healthcare were made to the states and territories as National Healthcare Specific Purpose Payments (SPP). During 2012–13, reforms to the national health funding arrangements came into operation. The National Health Reform Agreement was introduced with an aim to give greater control over funding of public hospitals to the Commonwealth Government. The implementation of a nationally consistent approach to funding acute admitted services, emergency department services and non-admitted patient services began on 1 July 2012, and for the remaining non-admitted services, mental health and subacute services, on 1 July 2013. The funding basis used is an Activity Based Funding (ABF) approach which is equivalent to the SPP, and from 1 July 2014, will also include various forms of 'efficient growth' funding. This means that funding will not only be linked to the growth in hospital activity, but that Commonwealth funding will be indexed by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and population growth each year.

Under this arrangement, ABF, which is provided through the pool account, involves the setting of a unit price for each type of medical or clinical activity, and agreement about the quantity of units to be provided by each of the hospitals. This forms the basis for calculating the funding to be provided under the health services' agreement (HSA) which is agreed to by each hospital and the respective state Minister for Health.

Block funding is also provided by the Victorian Minister for Health where appropriate, and is also set out in the annual HSA. Block funding is provided to hospitals when it is not technically possible to use ABF, or where there is an absence of economies of scale that mean some services would not be financially viable under ABF—this is mainly for regional and rural hospitals.

In 2012–13 and 2013–14, Commonwealth contributions to public hospitals in each state and territory were equivalent to the amount that would otherwise have been payable through the previous arrangements—these years were known as the transition years. From July 2014 to June 2017, funding will be linked to the level of services delivered by public hospitals. Each state's and territory's entitlement will be directly linked to the growth in public hospital activity provided in that jurisdiction. From 1 July 2017, the Commonwealth will also index its public hospitals' funding by CPI and population growth.

The National Health Funding Pool

Under these funding arrangements, state and territory governments remain responsible for the performance of public hospitals in their jurisdictions. However, Commonwealth and state ABF monies, as well as Commonwealth block funding, are paid into a bank account established for each state or territory—but controlled by the Commonwealth. The Victorian bank account is known as the National Health Funding Pool—Victorian State Pool Account.

ABF payments are made directly from the Pool to hospitals, circumventing the previous role of the state and territory health departments. Payments can only be made from the Pool following instruction from the relevant state or territory Minister for Health.

An independent administrator is required to manage each of the Commonwealth's, states' and territories' Pool accounts. The Administrator is required to oversee the payments made out of the Pool account, maintain the associated records, and prepare annual financial statements, which are to be audited and tabled in the Parliament of each relevant jurisdiction.

At the time of preparing this report, an administrator for Victoria had still not been appointed. The former Victorian Minister for Health had continued to temporarily grant—on a yearly basis—authority to the Chief Finance Officer of the former Department of Health to make payments out of the Pool account to Victorian hospitals.

The 2014–15 Commonwealth Budget states that the Commonwealth is planning to create a new Health and Productivity Commission that will be formed by merging the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, the National Health Performance Authority, the National Health Funding Body, and the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool. The Commonwealth Budget notes that during 2014–15, the government will consider, in consultation with the states, further rationalisation of government bodies, including the potential merging of these six health care bodies to create a Health Productivity and Performance Commission. The Victorian Auditor‑General is responsible for the audit of the financial statements of the National Health Funding Pool—Victorian State Pool Account. However, as the Pool does not form part of the operations of the Victorian public hospital sector, its financial results are not included in this report.

1.5 Conduct of public hospital financial audits

The audits of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of this report was $205 000.

2 Quality of reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results of the 2013–14 audits of the 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities. It compares the financial reporting practices in 2013–14 against better practice, and presents the results of our assessment of general internal controls across these entities.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the financial reports of public hospitals as all financial reports were given unmodified audit opinions.

Findings

- The average time taken to finalise public hospital financial reports reduced from 9.1 to 7.3 weeks in 2013–14 due to the efforts of management in preparing and finalising drafts of their financial statements earlier. This is well within the legislated time frame of 12 weeks.

- Financial report preparation by public hospitals could be further improved with the preparation of shell financial statements. This will enable early identification and resolution of financial reporting issues, thereby reducing the risk of delays and any associated additional costs. Around a third of public hospitals did not prepare shell financial statements during the 2013–14 financial year.

- Other areas of potential improvement relating to internal controls include timely reviews of key account reconciliations, timely authorisation of supplier payments and regular review of financial and information technology policies.

Recommendations

That public hospital boards and management:

- review their financial reporting processes to address the better practice report preparation elements, including the timely preparation of shell financial statements

- address all issues raised in audit management letters on a timely basis, including ongoing concerns regarding the need to improve controls around key account reconciliations and the authorisation of supplier payments.

2.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2013–14 financial statements of public hospitals and their associated entities.

In our annual audits we focus on the internal controls relating to financial reporting and assess whether entities have managed the risk that their financial statements may not be complete and accurate. Poor internal controls diminish management's ability to achieve their entity's objectives and comply with relevant legislation. They also increase the risk of fraud and error.

The board and management of each public hospital are responsible for developing and maintaining adequate systems of internal control that enable:

- preparation of accurate financial records and other supporting information

- timely and reliable external and internal reporting

- appropriate safeguarding of public assets

- prevention or detection of fraud, errors and other irregularities.

Integral to the annual financial audit is an assessment of the adequacy of the internal control framework, as it relates to financial reporting, and the governance processes. In making this assessment, consideration is given to the internal controls relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial report in order to design audit procedures that are appropriate in the circumstances, but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control.

In this Part we report on aspects of the general internal controls of Victoria's public hospitals and associated entities.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. An unmodified or 'clear' audit opinion confirms that the financial statements present fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of relevant Australian Accounting Standards and applicable legislation.

A modified audit opinion means that the financial report is materially different to the requirements of the relevant reporting framework, and is therefore less reliable and useful as an accountability document.

For 2013–14, unmodified audit opinions were issued on the financial statements of all 87 public hospitals and 23 associated entities. This positive result is consistent with 2012–13, when all 112 public hospitals and associated entities received unmodified audit opinions.

In certain circumstances an audit opinion may draw attention to, or emphasise, a matter relevant to the users of an entity's financial report but does not warrant a modification. No public hospital or associated entities' audit opinion included an emphasis of matter paragraph for 2013–14, consistent with 2012–13.

2.3 Quality of individual hospital financial reporting

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured in part by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report, as well as against better practice criteria.

Appendix C details the legislative and reporting framework for each of the 110 entities.

2.3.1 Accuracy

The frequency and size of errors in financial statements are direct measures of the quality of the draft financial statements submitted to audit. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments required as a result of an audit.

The public is entitled to expect that any financial reports that bear the Auditor‑General's opinion are accurate and of the highest possible quality. Therefore our expectation is that all entities will adjust any errors identified during an audit, other than those that are clearly trivial or clearly inconsequential to the financial report, as defined under the Australian Auditing Standards.

Material audit adjustments

Material errors need to be corrected before an unmodified audit opinion can be issued. While all material errors were adjusted prior to the completion of the financial reports, it is noted that 51 material audit adjustments were made during the 2013–14 audits. This compares to 81 material audit adjustments in 2012–13. Rural hospitals continue to account for just over half (53 per cent) of the material adjustments made each year.

The nature of material financial balance and disclosure adjustments identified during the 2013–14 audits were:

- property, plant and equipment disclosures—the introduction of Australian Accounting Standard AASB13 Fair Value Disclosuresrequired all entities to disclose significantly more information regarding the nature of assets held, and the factors used in determining their valuations in their 2013–14 financial statements than in prior years. Across the 110 entities in this report, material adjustments were made as a result of the audit of these disclosures

- financial statement and accounting policy disclosures—adjustments to financial statements to bring overall disclosures into line with the sector's model financial report, and therefore the requirements of the financial reporting framework, and specific adjustments relating to accounting policy disclosures, particularly related to Australian Accounting Standards AASB13 Fair Value Measurementand AASB119 Employee Benefits

- depreciation—adjustments to depreciation costs recognised in the financial statements, where entities had incorrectly calculated depreciation costs as part of the asset revaluation process

- cash and investments—incorrect reclassification of cash balances to investments for deposits held with maturity terms in excess of 90 days. All material errors were adjusted prior to the completion of the financial reports.

Adjustment of other misstatements

Other errors should also be corrected before the financial report is finalised. While some errors may appear immaterial in isolation, in aggregate, a series of small errors may have a significant impact on the statements or an entity's operating result.

During the 2013–14 audits, a number of misstatements above clearly trivial thresholds were identified. The majority of these were subsequently adjusted in entities' financial statements. However, some were not adjusted because they were identified late in the audit, or could not be processed in a timely manner without raising the risk of creating further errors. In these instances the misstatement was raised with management and will be rectified during 2014–15.

2.3.2 Timeliness

Timely financial reporting is key to providing accountability to stakeholders and enables well‑timed and informed decision-making by users of financial reports. The later the reports are produced and published after year end, the less useful they are.

Public hospitals are required to finalise their audited financial reports within 12 weeks of the end of the financial year, and they are to be tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of the financial year. The need to consolidate the results of controlled entities into their financial report means that the financial statements of controlled entities, that sometimes operate under the Corporations Act 2001, are also required to report within 12 weeks of the end of financial year.

All public hospitals met their legislative time frames for the production and audit of financial statements, as was the case in 2012–13. All associated entities met their time frames in 2013–14, an improvement on 2012–13, when two entities missed their legislative reporting requirements.

The average time taken to finalise financial statements decreased to 7.3 weeks in 2013–14 from 9.1 weeks in 2012–13. This reduction was due to the efforts of management in preparing and finalising drafts of their financial statements earlier, which was in response to the reduced reporting time lines imposed by the Department of Treasury and Finance and improved timing of the completion of the National Health Funding Pool—Victorian State Pool Account (the Pool) financial statements—which enabled earlier finalisation of individual hospital financial statements, to ensure that funds distributed from the Pool were accurately reflected in hospital statements.

2.3.3 Better practice

An assessment of the quality of financial reporting processes was conducted against better practice criteria, detailed in Appendix C, using the following scale:

- no existence—function not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting process

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however, it is not fully effective

- better practice—entity has implemented effective and efficient processes.

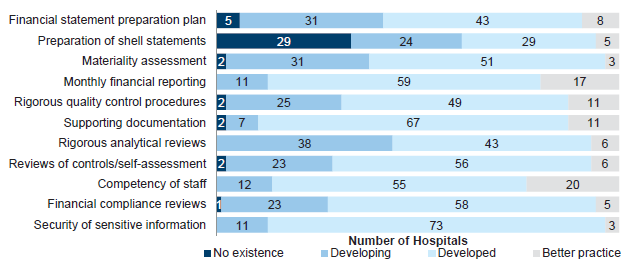

The results are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Results of assessment of report preparation processes against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

While most elements were developing or developed, and some hospitals had achieved better practice, the most significant element to be addressed across the sector is the preparation of shell financial statements. Preparing shell financial statements before year end enables format, presentation and disclosure issues within the financial statements to be identified and resolved early. Conversely, not preparing shell financial statements in advance of year end can cause significant delays and additional costs in the finalisation of the financial statements—potentially jeopardising the ability to meet legislated time lines and causing unnecessary cost increases.

Assessments against better practice elements have been reported over a number of years. Nevertheless, some public hospitals have not sufficiently developed some better practice elements which are designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their financial report preparation.

2.4 General internal controls

Internal controls at public hospitals and their associated entities were adequate for maintaining the reliability of external financial reporting. Nevertheless, the following areas were commonly identified as requiring improvement:

- timely review of key account reconciliations—reported in the prior year

- review and documentation of master file standing data changes—reported in the prior year

- authorising supplier payments

- review of financial and information technology policies

- resolution of prior year issues.

The issues regarding review of key account reconciliations and review of master file standing data changes were reported in previous years, and while there has been progressive improvement by the hospital sector as a whole, further improvement is required by some public hospitals to ensure strong controls over financial reporting.

The control weaknesses were brought to the attention of boards, hospital management, and audit committees by way of our management letters.

2.4.1 Preparing and reviewing key account reconciliations

A financial report is prepared from information captured in an entity's general ledger, with key general ledger balances supported by information in subsidiary ledgers such as accounts payable, fixed assets and payroll. Periodic reconciliation of the general ledger with subsidiary ledger balances confirms the completeness and accuracy of data.

Timely and independent reviews of reconciliations decreases the risk that errors may go undetected or may not be resolved in a timely manner. Poor controls can adversely affect the accuracy of financial reporting.

Nine (10 per cent) of the 87 public hospitals (12 hospitals, or 14 per cent in 2012–13) had deficiencies in the preparation and review of key reconciliations. While these nine hospitals prepare reconciliations regularly, independent reviews of the reconciliations either did not occur, or were not documented in a timely manner. This issue was reported last year and while improvement has been observed, further improvement is required, predominantly in rural hospitals.

2.4.2 Review and documentation of master file standing data changes

Financial systems, such as accounts payable and payroll systems rely on the maintenance of master files holding standing data to enable reliable processing of individual payments. The standing data can include important details such as names, addresses, pay rates and bank account details.

It is important that all changes to master file standing data are independently checked for completeness, accuracy and legitimacy. Without checks, processing errors can be repeated many times over, reducing data integrity. An independent review of master file standing data changes is important for the detection and timely correction of unintentional or fraudulent changes, and to guard against payments to fictitious parties.

Five (6 per cent) of the 87 public hospitals (11 hospitals, or 13 per cent in 2012–13) had weaknesses in maintaining key system master files, including a lack of an independent review of changes made, and inadequate documentation to support them. This issue was most prevalent in metropolitan hospitals, with Dental Health Services Victoria in particular, failing to improve its review of payroll master file changes over the last few years.

2.4.3 Authorising supplier payments

The implementation and maintenance of an effective internal control framework over expenditure processing is required. The regular review of financial delegations and user access to online banking is necessary to reduce the risk of inappropriate transactions.

Nine (10 per cent) of the 87 public hospitals (five hospitals, or 6 per cent, in 2012–13) had weaknesses identified within their expenditure transaction process during 2013–14. These related to:

- approvals not being made within established financial delegations

- lack of review of financial delegations

- inappropriate user access to online banking.

2.4.4 Review of financial and information technology policies

Policies provide a frame of reference for staff, and communicate management's expectations in relation to particular activities. They set out requirements for the processing of authorised transactions. In the absence of documented policies, the opportunity for fraud risk and likelihood of error increases.

Public hospitals generally had policies in place to address their key financial processes. However, there were 11 out of the 87 hospitals where policies were out of date and not being regularly reviewed. This included policies relating to asset maintenance, fraud and information technology. Eight of these 11 hospitals were rural.

2.4.5 Resolution of prior year issues

Internal control weaknesses reported to an entity's board, management and audit committee should be actioned and resolved in a timely manner.

Across the 87 public hospitals, 106 of the 358 (30 per cent) internal control weaknesses identified and reported to the hospital boards by VAGO during the 2012–13 audits, or earlier, had not been resolved by management at the time of the 2013–14 audits. This lack of timely resolution means that the control frameworks in place at these entities are not as effective as they should be, and management should seek to address all issues raised on a timely basis.

Recommendations

That public hospital boards and management:

- review their financial reporting processes to address the better practice report preparation elements, including the timely preparation of shell financial statements

- address all issues raised in audit management letters on a timely basis, including ongoing concerns regarding the need to improve controls around key account reconciliations, the authorisation of supplier payments, and the regular review of financial and information technology policies

- through audit committees, implement appropriate monitoring mechanisms to ensure audit findings are resolved by management on a timely basis.

3 Financial results

At a glance

Background

This Part provides an insight into the financial results and financial sustainability risks of the 87 public hospitals based on an analysis of key financial indicators.

Conclusion

The overall financial sustainability risk for the public hospital sector at 30 June 2014 has been rated as medium, consistent with the prior year.

Findings

- The financial reports of 32 public hospitals (28 for 30 June 2013), including some major metropolitan hospitals, were supported by a letter from the former Department of Health. The letter stated the department would provide financial support to enable these public hospitals to meet their financial obligations, if required. Without this support, these 32 public hospitals would have been unable to report as a going concern at 30 June 2014.

- Twelve public hospitals at 30 June 2014 (23 at 30 June 2013) had cash on hand at balance date sufficient to fund only one week or less of operations.

- The current funding model has resulted in a mismatch between public hospital boards' responsibilities for the sustainable management and provision of health services and the boards' limited ability to control the funding they receive—particularly from the department—to enable them to do this.

Recommendations

That public hospital boards and management:

- maintain good cash management processes to ensure that they are able to meet their financial obligations as they fall due, particularly for those public hospitals assessed as having a high liquidity risk

- work with the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure they are able to renew ageing assets as required to prevent any loss of services provided to the public.

3.1 Financial results of public hospitals

3.1.1 Operating result

Public hospitals, as an essential public service, should manage their finances so that they are financially sustainable. The sector's net result for 2013–14 was a surplus of $235 million, which against total revenue of some $13 billion for all entities in the sector is tantamount to a break even position.

Total public hospital revenue increased by 7 per cent in 2013–14 to $12.8 billion, and expenditure increased by a corresponding 5 per cent. The composition of what makes up revenue and expenditure for public hospitals has remained basically unchanged over the past five years. Government funding contributes 88 per cent of public hospital revenue, and salaries and wages are the biggest expense—representing 67 per cent of expenditure.

Public hospitals derive and report revenue as either:

- revenue arising from health services agreements (HSA income)—which is largely made up of government funding

- revenue from hospital and community initiatives (non-HSA income).

Non-HSA income is self-generated and is typically derived from additional services such as pharmacy sales, cafeteria sales, diagnostic imaging, private practice fees, car park fees and income on investments.

Rural and regional public hospitals derive 92 per cent of their revenue from HSA income. This means rural and regional hospitals have little self-generated revenue. In contrast, metropolitan public hospitals generate 86 per cent of their revenue from HSA income and therefore have slightly more capacity to fund initiatives and absorb unexpected cost fluctuations.

3.1.2 Financial position

An entity's financial position is generally measured by reference to its net assets—the difference between its total assets and total liabilities. The strategic objectives for public hospitals are aligned to providing key health services to the public, and they hold significant asset balances to do this—including buildings, medical equipment and infrastructure.

The total assets of the sector were $14.6 billion at 30 June 2014 ($12.0 billion at 30 June 2013). Net assets at 30 June 2014 were $9.8 billion ($7.5 billion at 30 June 2013). This positive net asset position improved during 2013–14 as large scale capital projects progressed—such as the new Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre—and other smaller capital projects were completed. Corresponding liabilities for some of these capital projects were recognised. Furthermore, the revaluation of property, plant, and equipment undertaken in line with the Australian Accounting Standard AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement and Financial Reporting Direction 103E Non-Financial Physical Assets (FRD 103E) contributed to the improved net asset position in 2013–14.

3.2 Financial sustainability risks of public hospitals

3.2.1 Introduction

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet their current and future expenditure requirements as they fall due. They also need to absorb foreseeable changes and financial risks that materialise. The assessment of financial sustainability risks assists in identifying trends that either warrant attention or highlight positive results.

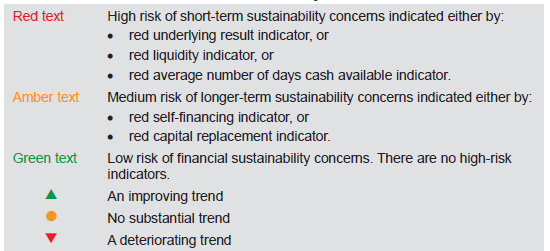

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both short- and long-term perspectives. Short-term indicators show the ability of an entity to maintain positive operating cash flows in the near future, or to generate an operating surplus in the next financial year. Long-term indicators focus on strategic issues, such as the ability to fund ongoing asset maintenance programs or reduce long-term debt.

In this Part, insight is provided into the financial sustainability risks of public hospitals through analysis of key financial sustainability indicators as at 30 June 2014, and trends in these indicators over the past five years. Appendix D describes the sustainability indicators and their significance, as well as the risk assessment criteria and rating scales used in this Part.

The analysis addresses the financial position of the sector as a whole, of the three categories of hospitals—metropolitan, regional and rural—and of individual public hospitals.

To form a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability, a holistic analysis that moves beyond, but includes, financial indicators would be required, including an assessment of the entity's operations and the regulatory environment in which the entity operates. These additional considerations are not examined in this report.

3.2.2 Overall assessment

The overall financial sustainability risk for the public hospital sector for 2013–14 was assessed as medium, consistent with the 2012–13 result. This assessment means there are concerns relating to the financial sustainability risks of many public hospitals.

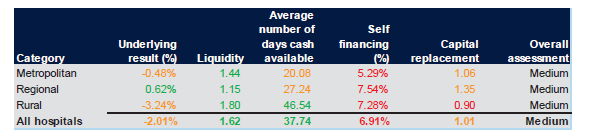

Figure 3A presents the indicators by hospital category for 2013–14.

Figure 3A

Financial sustainability risk, 2013–14

Note: Red identifies high risk, while amber indicates longer-term sustainability risks and green indicates no significant risks.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The results of our sustainability risk assessments for each hospital category and each public hospital can be found in Appendix D. Comments on the results for each of the indicators follow in this Part.

Impacts of the funding model on sustainability

The funding arrangements directly impact the financial sustainability risks of public hospitals. For public hospitals to continue to provide an adequate and sustainable level of service, their assets need to be maintained and replaced when necessary. However, the funding model does not progressively provide funding to public hospitals to match the depreciation of their assets. Capital grants, which may be provided for asset renewal and replacement, are allocated by the Department of Health and Human Services—the former Department of Health (DH)—strategically across the sector.

The impact on public hospitals is demonstrated as follows:

- sixty-nine public hospitals (79per cent) had a high self-financing risk in 2013–14 (70 hospitals in 2012–13)

- sixteen public hospitals (18 per cent) had a high liquidity risk in 2013–14 (15 hospitals in 2012–13)

- twelve public hospitals (14 per cent) held cash at 30 June 2014 that could only fund seven or less days of operating activity (23 hospitals in 2012–13)

- in 2013–14, 33 public hospitals (38 per cent) received capital grants of less than 20 per cent of their depreciation expense for the year. This means the funding received for replacing their assets was significantly less than the value of assets they consumed, as measured by the depreciation expense.

Under section 33 of the Health Services Act 1988 (the Act), the functions of a public hospital's board are to oversee and manage the hospital, and to ensure that services provided comply with the requirements of the Act and the hospital's objectives. Section 65 of the Act requires the boards to develop plans to ensure the 'long term financial viability of the public health service'.

Nevertheless, under the funding model managed by DH, hospital management and boards have limited control over pricing and funding models—which are determined by DH—whilst remaining accountable for the impacts of ageing infrastructure and associated expenditure. The mismatch between the governance and funding models blurs accountability for the financial performance of individual hospitals.

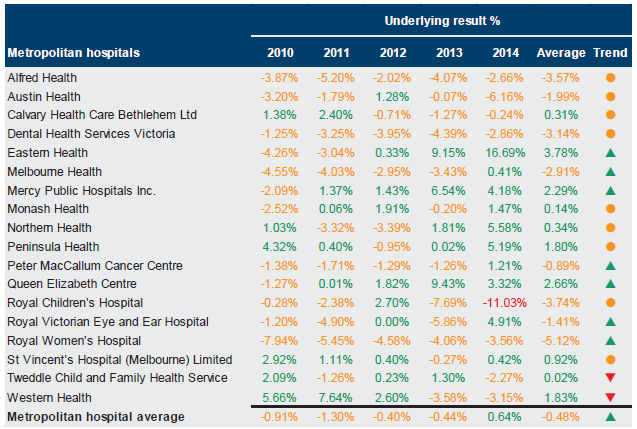

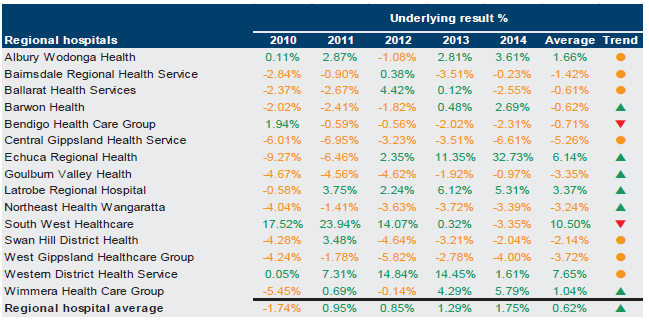

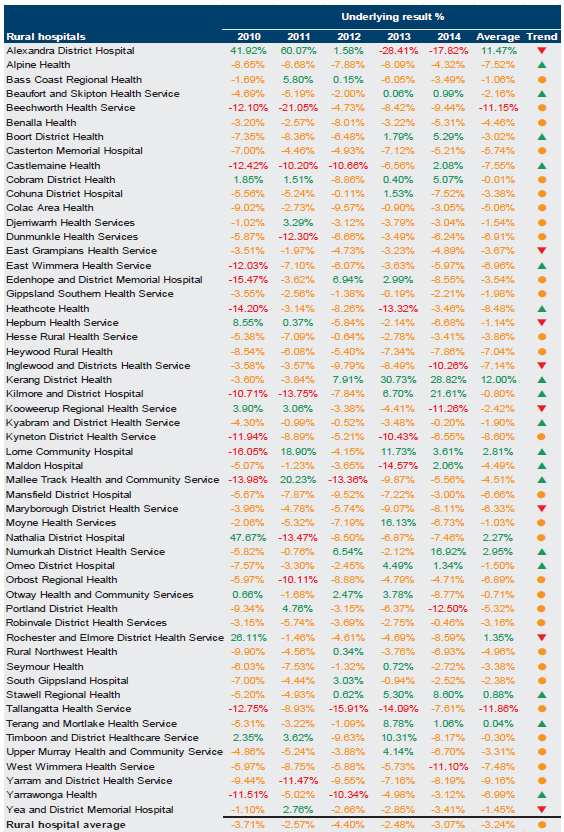

3.2.3 Net result

Net result is calculated by subtracting an entity's total expenses from its total revenue, to show what was earned or lost in a given period of time. A positive result is known as a surplus, while a negative result is known as a deficit.

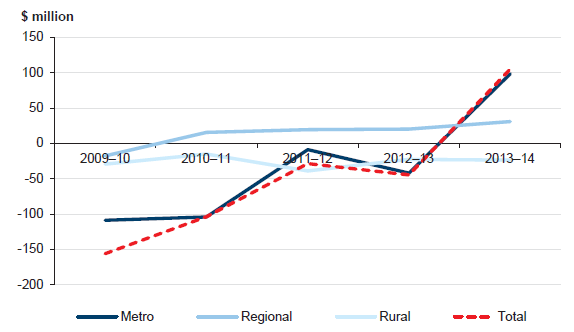

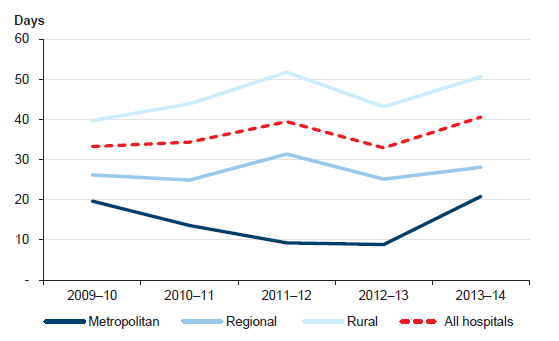

Figure 3B shows the average net result for each public hospital category, and overall, from 2009–10 to 2013–14.

Figure 3B

Net result by hospital category and overall

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The net results by category have fluctuated significantly over the five-year period and continue to improve towards an average surplus position in 2013–14. All categories have achieved some recovery since the large losses delivered in 2009–10, which were largely due to significantly increased depreciation costs following from the sector-wide asset revaluations performed in 2008–09. Under the funding model, DH does not fund public hospitals directly for depreciation, and it is expected that public hospitals will record operating deficits as they incur increased depreciation charges in the financial year following asset revaluations. As per FRD 103E, the sector wide asset revaluations operate on a five year cycle. The public hospital valuations—occurred during the 2013–14 year—so we expect this pattern of an increase in depreciation costs to repeat in our analysis of the 30 June 2015 hospital financial statements.

Overall, metropolitan hospitals have achieved a surplus in the current year, the majority of which have been driven by significant state government capital grants isolated to a small number of hospitals.

Regional hospitals have continued to sustain average surpluses in recent times. These averages are impacted by consistently strong results from a number of hospitals due to their increasing emphasis on cost containment measures, which has subsequently increased the average result of the category as a whole.

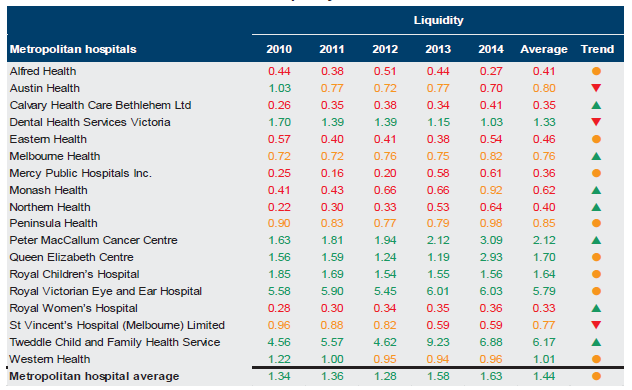

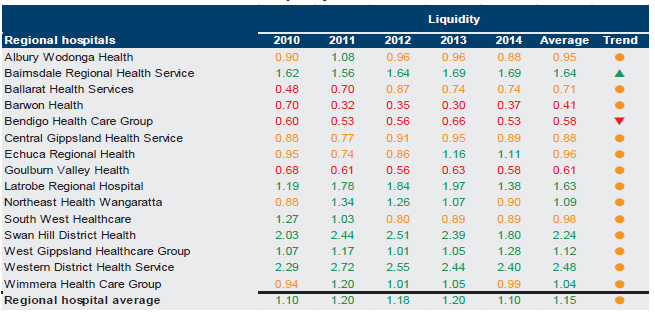

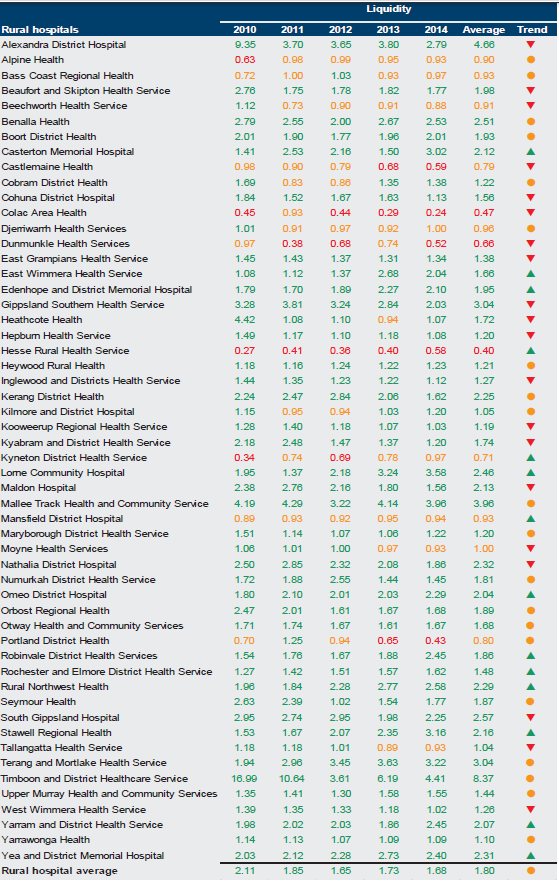

3.2.4 Liquidity

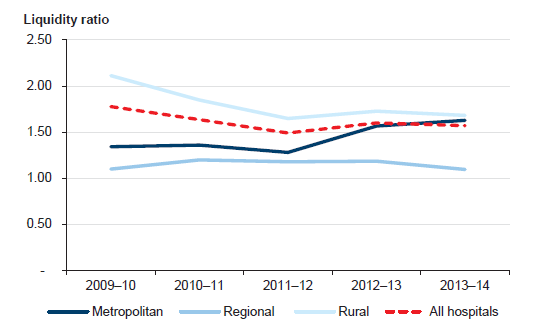

Liquidity is a measure of current assets against current liabilities. This measures the ability of an entity to pay existing liabilities in the next 12 months. A ratio of one or more means there are more current assets than current liabilities.

At 30 June 2014, 33 of 87 public hospitals had fewer current assets than current liabilities (33 in 2012–13). This means they face potential challenges of not being able to pay liabilities as and when they fall due. Low liquidity highlights the pressure on public hospitals to meet short-term liabilities.

Figure 3C shows that the average liquidity ratio by hospital category has remained relatively stable over the past five years.

Figure 3C

Average liquidity ratio, by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

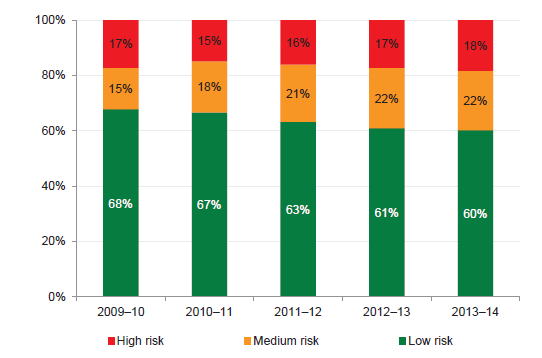

Average liquidity ratios and the number of public hospitals with significant liquidity risks have generally remained stable, but are increasing for some hospitals. Figure 3D shows the risk profile over the past five years, with the number of public hospitals in the high- and medium-risk categories growing slightly over prior periods.

Figure 3D

Public hospital liquidity risk

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These liquidity issues are largely driven by the funding model that governs hospital operations, which restricts the ability of public hospitals to be financially self-sufficient. Public hospitals are funded on a monthly basis for the costs they are expected to incur over the next month.

This is a change from recent years where funding was provided on a fortnightly basis. This model requires detailed cash management practices to be implemented by public hospitals to ensure they are able to pay their debts as they fall due. Given their heavy reliance on government funding to maintain operations and service levels, public hospitals must closely manage their cash flow budgets.

DH also monitors the liquidity and cash flows of hospitals at an overall level to ensure funds are appropriately deployed.

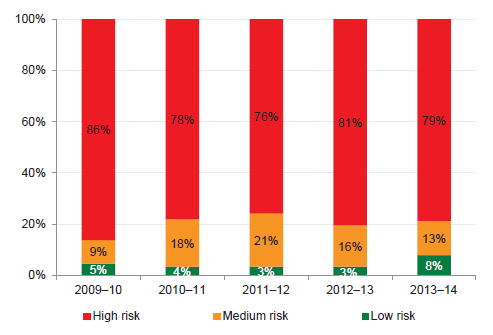

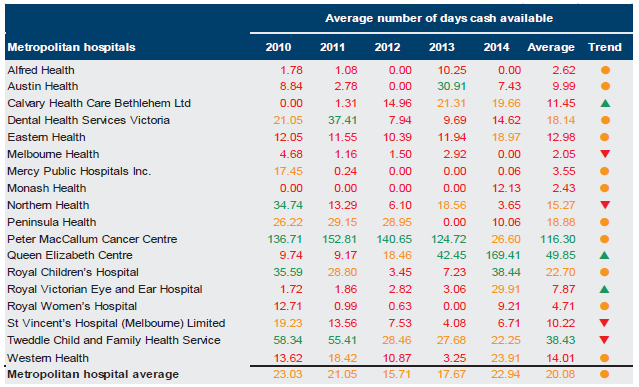

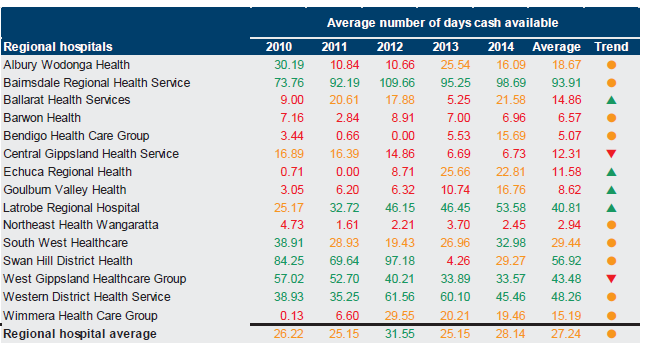

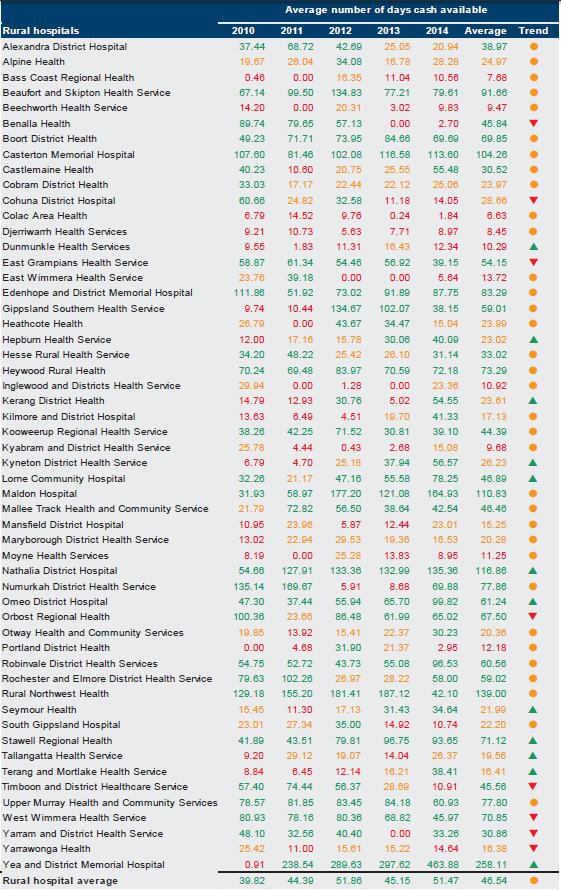

Average number of days cash available

The 'average number of days cash available' indicator measures the number of days of operating expenses that a hospital could pay with its current, unrestricted, cash balance. Under the Australian Accounting Standards certain assets, such as term deposits with original maturities of more than 90 days, are specifically excluded from cash. For the purposes of accuracy and consistency across all public hospitals, this indicator therefore excludes these particular assets.

The calculation of unrestricted cash also excludes amounts held by a public hospital where the use of these amounts has been restricted—such as patient money held in trust or cash set aside for capital purposes. These amounts are excluded from this indicator, as they cannot be used by the public hospital to cover their day-to-day operating costs.

At 30 June 2014, 48 of 87 public hospitals (57 of 87 at 30 June 2013)—including most major metropolitan and regional hospitals—had cash holdings equivalent to 30 days or less of their operating cash outflows. Figure 3E shows the risk profile over the past five years, with the number of public hospitals in the high- and medium-risk categories reducing in 2013–14.

Figure 3E

Public hospital average number of days cash available risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3F shows that the average number of days of cash available at year end increased at the whole-of-sector level, and remained greater than one month's operating cash flows as at 30 June 2014. This improvement has been largely attributed to improved cash on hand at year end, driven primarily by improved cash management strategies employed by hospitals to reduce potential liquidity challenges at year end.

This has led to a greater cash balance being held by individual public hospitals as at the 30 June 2014 balance date compared to the prior year, which is also illustrated by the more favourable risk profile in figure 3E.

Figure 3F

Average number of days cash available, by hospital category

Note: Funds held in trust, unspent capital grants and restricted special purpose funds are excluded from this analysis as their use is restricted.

Note: Holdings in short-term investments, such as such as term deposits, are also excluded from this analysis, in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Twelve public hospitals (23 in 2012–13) held unrestricted cash equivalent to seven days or less than seven days of operating expenditure at 30 June 2014. The 12 hospitals are listed in Figure 3G.

This means that these hospitals could potentially only continue to operate for up to a week if they did not receive further funding at the start of July 2014. While this is an improvement on the prior year result of 23 public hospitals being in this position, it means that public hospitals are still at a significant risk of not being able to fund operating activities. Further, if these hospitals did not receive a grant payment during that seven day period, they would be required to access other funding sources, which may include seeking a recallable grant from the department.

Ultimately, holding a low cash on hand balance could put at risk the ability of these hospitals to respond in the event of unexpected costs, which may result in money being diverted from other services to meet any new obligations.

Figure 3G

Public hospitals with cash holdings of seven days or less operating cash outflow, 30 June 2014

|

Hospital |

Days cash available |

|---|---|

|

Alfred Health |

0 |

|

Melbourne Health |

0 |

|

Mercy Public Hospitals Inc. |

0 |

|

Colac Area Health |

2 |

|

Northeast Health Wangaratta |

3 |

|

Benalla Health |

3 |

|

Portland District Health |

3 |

|

Northern Health |

4 |

|

East Wimmera Health Service |

6 |

|

Central Gippsland Health Service |

7 |

|

Barwon Health |

7 |

|

St Vincent's Hospital (Melbourne) Limited |

7 |

Note: Where a hospital's unrestricted cash balance is less than zero, it has been rounded to zero days cover.

Note: Funds held in trust, unspent capital grants, restricted special purpose funds and holdings in short-term investments, such as such as term deposits, are excluded from this analysis.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

It should be noted that none of these hospitals ceased to operate after 30 June 2014 within the number of days specified in Figure 3G. However, by operating in this tightened fiscal environment, these hospitals are reducing their ability to quickly respond to any unexpected changes in circumstances. All public hospitals need to operate good cash management services to address this risk.

Going concern

Notwithstanding the overall financial results achieved by the sector in 2013–14, 32 public hospitals (28 in 2012–13) showed signs of financial stress, with a material uncertainty about their ability to continue as a going concern for financial reporting purposes. This means that they are considered to be at risk of not being able to meet all their obligations—such as creditors, borrowing repayments and other expenses—over the next 12 months.

To counteract this possibility, DH provided letters of financial support to these 32 hospitals (28 in 2012–13). These letters provide an undertaking by DH to provide adequate cash flows to enable them to meet their current and future obligations, as and when they fall due, for a period of 12 months up to September 2015, should it be required.

While these letters do not provide for additional funding, they mitigate the risk that the 32 hospitals will be unable to meet all of their financial obligations as they fall due during 2014–15.

Figure 3H shows the public hospitals that received a letter of support related to their 2013–14 financial reports. By providing a letter of support, DH has assisted these public hospitals in meeting the requirements of Australian Accounting Standard AASB 101 Presentation of Financial Statements for the entity to report as a going concern. This means that the hospitals are able to meet their financial obligations for the next 12 months after the financial statements were signed.

Figure 3H

Public hospitals with letters of support, 2013–14

|

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Rural |

|---|---|---|

|

Alfred Health Austin Health Eastern Health Melbourne Health Monash Health Northern Health Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Royal Children's Hospital The Royal Women's Hospital |

Albury Wodonga Health Ballarat Health Services Bendigo Health Care Group Central Gippsland Health Service Cohuna District Hospital Colac Area Health Northeast Health Wangaratta Swan Hill District Hospital Wimmera Health Care Group |

Alexandra District Hospital Bass Coast Regional Health Beechworth Health Service Castlemaine Health Djerriwarrh Health Services Dunmunkle Health Services East Wimmera Health Service Kilmore and District Hospital Kyneton District Health Service Maryborough District Health Service Portland District Health Rural Northwest Health Tallangatta Health Service West Wimmera Health Service |

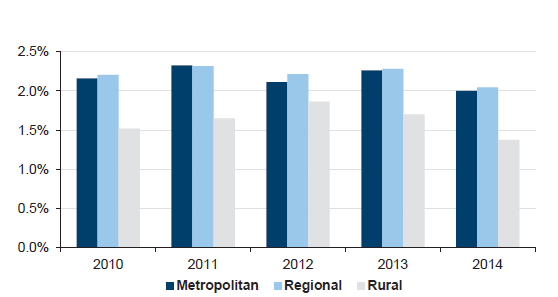

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

As noted earlier, hospitals will need to continue to monitor their cash management practices carefully to ensure they are able to continue to provide services to the public, while still meeting their financial obligations.

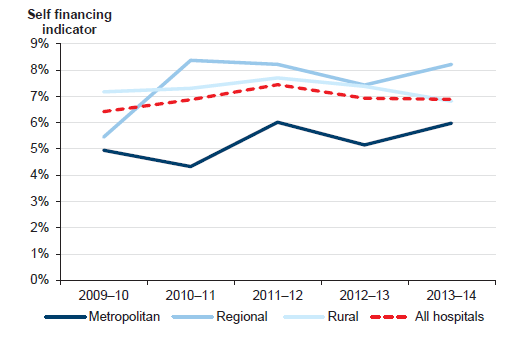

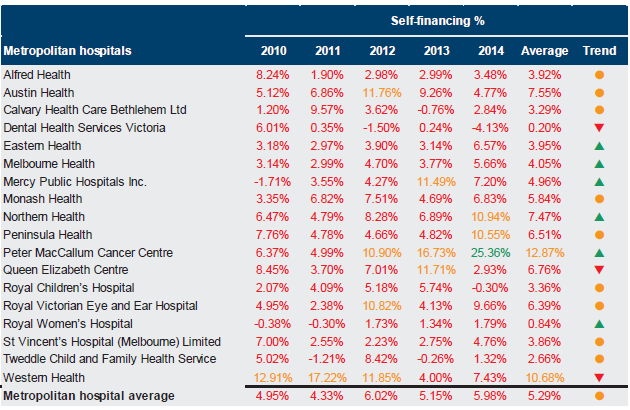

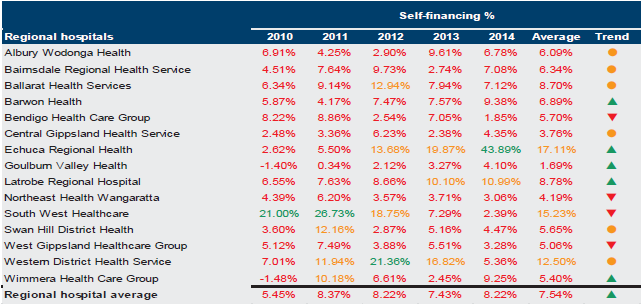

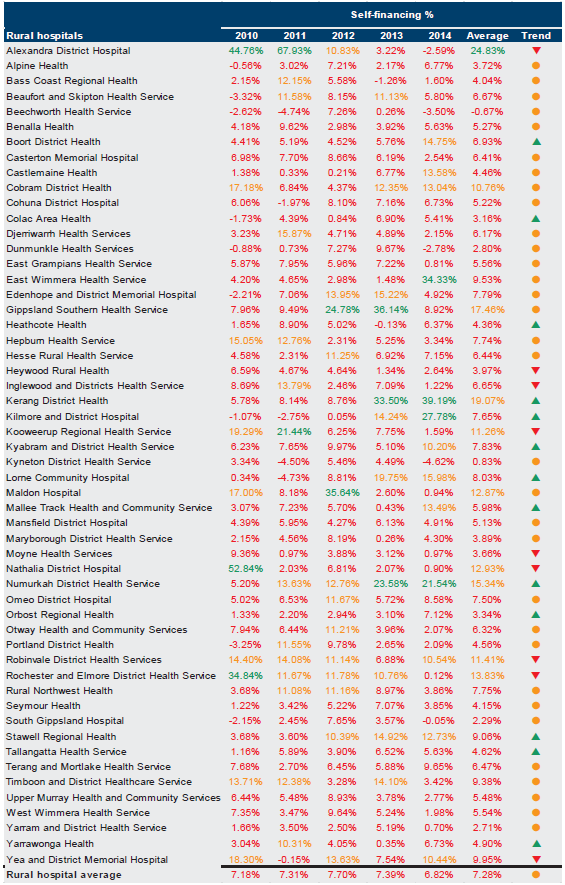

3.2.5 Self-financing

The self-financing indicator measures the ability of an entity to replace assets using cash generated by its own operations. The higher the percentage, the more effectively this can be done. This is a longer-term indicator.

Across the sector, the average self-financing ratio remained low, highlighting the sector's ongoing reliance on government funding to maintain service levels and to maintain and replace assets. In 2013–14, metropolitan hospitals continued the trend of the past four years, with lower self-financing ratios than regional and rural hospitals.

Figure 3I shows the movement in the average self-financing ratio for each of the three hospital categories over the past five years.

Figure 3I

Average self-financing indicator, by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3J shows that the self-financing risk for 79 per cent of public hospitals was high for 2013–14. This is consistent with results since 2009–10, and is largely due to the funding model.

Figure 3J

Public hospital self-financing risk

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These results are reflective of the funding model and the nature of services provided by public hospitals. Changes to this model are outside the responsibility of individual public hospital boards. DH advises the state government on funding of public hospitals.

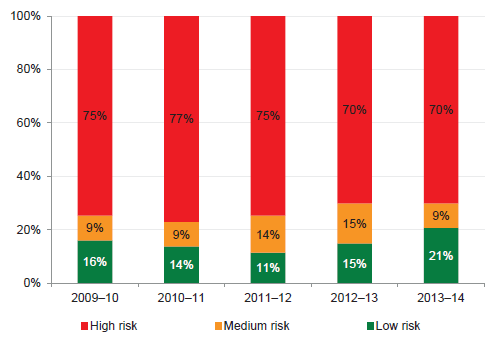

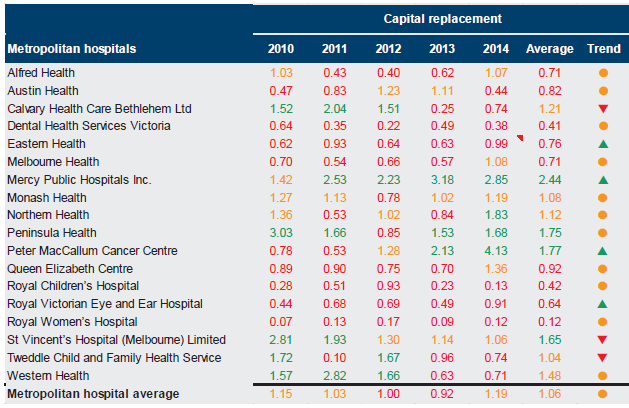

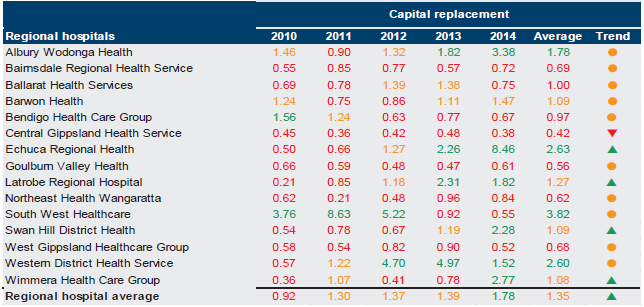

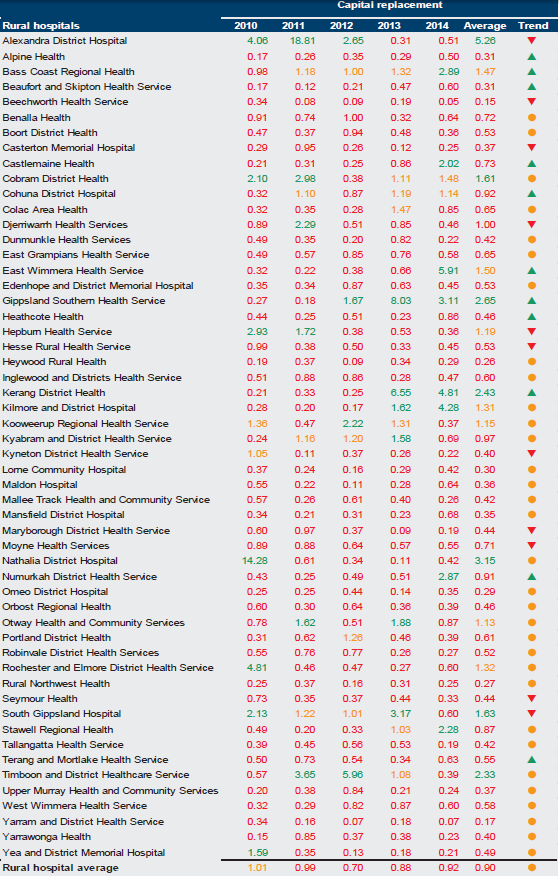

3.2.6 Capital replacement

The capital replacement indicator compares the rate of spending on infrastructure with an entity's depreciation. Depreciation is a measure of the value of a hospital's infrastructure that has been consumed in the year. Ratios higher than 1:1 indicate that spending on fixed assets is greater than depreciation for the year. This is a long-term indicator, as capital expenditure can be deferred in the short-term if there are insufficient funds available from operations, and borrowing is not an option.

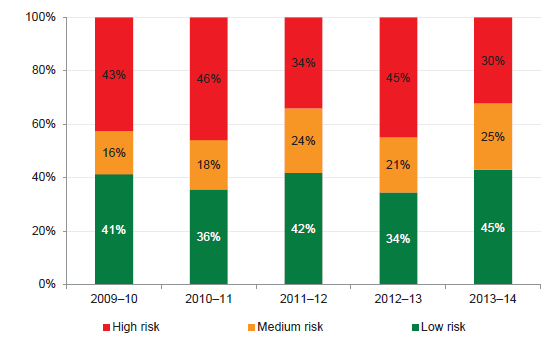

Figure 3K shows that the number of public hospitals with a high capital replacement risk has reduced since 2009–10, but remains very high.

Figure 3K

Public hospital capital replacement risk

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The value of assets across the sector increased since 2009–10, due to the 2013–14 revaluation of non-current assets, increasing depreciation charged annually and affecting the capital replacement indicator. The 2013–14 results show that the proportion of public hospitals in the low-risk category has increased moderately.

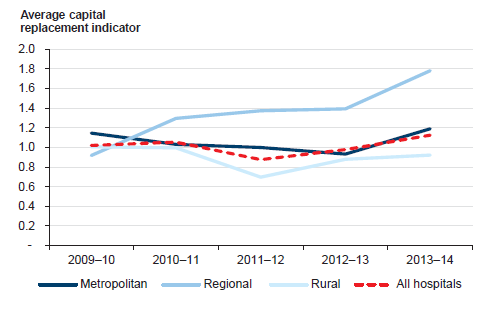

Figure 3L shows that after 2009–10, the sector's overall capital replacement ratio dropped in 2011–12, and was at its highest in 2013–14.

Figure 3L

Average capital replacement indicator, by hospital category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

On average, metropolitan and regional public hospitals are spending money on assets at a rate greater than they are being consumed. However, the positive results are based on an analysis that includes expenditure on both renewing assets and new capital projects. This may mean that for public hospitals where new assets are being acquired, existing assets are not being maintained at the rate they are being used—as measured through depreciation.

Where this is the case, there are challenges for the individual public hospitals—and DH—to ensure that fixed assets are not allowed to degenerate to a point where they are obsolete, and cannot be used to provide services to the public.

DH has provided $871 million in capital grants to public hospitals in 2013–14 to assist in the building of new assets. However, emphasising the trend in Figure 3L, these grants have been awarded more towards the metropolitan and regional public hospitals.

As shown in Figure 3L, rural public hospitals are not spending as much on renewing assets or building new assets compared to their consumption of current assets. This poses an even greater risk that these public hospitals may not be able to continue to provide services due to poor or obsolete assets in the medium to long term. These entities should work with DH to ensure assets at risk are renewed in appropriate time frames to prevent any loss of services to the public.

Recommendations

That public hospital boards and management:

- maintain good cash management processes to ensure that they are able to meet their financial obligations as they fall due, particularly for those public hospitals assessed as having a high liquidity risk

- work with the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure they are able to renew ageing assets as required to prevent any loss of services provided to the public.

4 Internal audit

At a glance

Background

Internal audit is a key mechanism available to public hospital boards to support the discharge of their governance and oversight responsibilities. Internal auditors can, among other activities, review core internal controls and identify areas of risk within an entity.

Conclusion

Public hospital internal audit functions generally operate effectively, although two public hospitals do not currently have an internal audit function in place, breaching the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

Areas of improvement to the internal audit functions have been identified to enhance the level of assurance received by public hospitals.

Findings

- Dunmunkle Health Service and Casterton Memorial Hospital do not maintain an internal audit function, breaching the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance under the Financial Management Act 1994.

- Thirty of the remaining hospitals do not have stand-alone internal audit charters.

- Internal audit plans are established at a majority of public hospitals, but they are not always aligned to the entity's risk register.

Recommendations

That Dunmunkle Health Service and Casterton Memorial Hospital establish and maintain an internal audit function.

That public hospital boards and management:

- have in place stand-alone internal audit charters that provide a clear framework for the selection, operation and oversight of the internal audit function

- review their internal audit plan to ensure that the internal audit function is providing the level of assurance required.

4.1 Introduction

Internal audit is a key mechanism available to public hospital boards to support the discharge of their governance and oversight responsibilities. Internal auditors can, among other activities, review core internal controls and identify areas of risk within an entity, providing assurance to boards, management on the operational effectiveness of key controls.

An effective internal audit function strengthens internal controls, adding credibility to both the financial and non-financial information produced, as well as improving the efficiency of key controls and processes.

This Part reviews the internal audit function in each of the 87 public hospitals against the better practice framework.

4.2 Key elements of an internal audit framework

The key elements of an effective internal audit function are detailed in Figure 4A. The table draws on the Australian National Audit Office better practice guide Public Sector Internal Audit – An Investment In Assurance and Business Improvement (September 2012).

Figure 4A

Key elements of an effective internal audit function

|

Key area |

Best practice criteria |

|---|---|

|

Policy |

Policy established that requires an effective internal audit function to be in place. Established internal audit charter, which documents:

Compliance with the Financial Management Act 1994 and Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance. Periodic review of the internal audit charter. Policy and charter appropriately reviewed and approved. |

|

Management practices |

Comprehensive audit plan developed for a minimum three-year period that is directly linked to the identified risks of the entity. Internal audit plan should:

Internal audit plan should be available to all stakeholders and staff. Ensure the head of internal audit is sufficiently senior to be an accepted element of the portfolio department's governance arrangements. Communication between internal audit and external audit is adequate. Regular reporting to the audit committee and the secretary. |

|

Governance and oversight |

Charter reviewed by the audit committee, and approved by the Secretary. Annual review of internal audit performance by the audit committee. Regular reporting to the audit committee on: