Regional Growth Fund: Outcomes and Learnings

Overview

This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the Regional Growth Fund (RGF), the achievement of its intended outcomes and whether the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has applied the lessons learned from the RGF to the planning and implementation of the Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund (RJIF).

Weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF mean that the department cannot fully demonstrate that value for money and the goals and objectives of the RGF have all been achieved to date. These weaknesses include a lack of transparency in pre-application processes and fundamental flaws in performance evaluation and reporting.

Regional Development Victoria (RDV) has not effectively monitored and reported on all the outcomes of the RGF. The reported outcomes of jobs and investment leveraged are potentially misleading as they inflate the actual achievements of the RGF. Reported job numbers primarily relate to expected, rather than actual jobs created. Consequently, reported RGF figures do not provide an accurate picture of actual achievements.

Going forward, the department is applying the lessons learned to the design and implementation of the new RJIF including a stronger evaluation framework. However, given RJIF's recent implementation, it is too early to determine the effectiveness of these improvements.

Regional Growth Fund: Outcomes and Learnings: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER September 2015

PP No 91, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Regional Growth Fund: Outcomes and Learnings.

This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the Regional Growth Fund (RGF), the achievement of the intended outcomes and whether the lessons learned from the RGF have been applied to the planning and implementation of the Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund (RJIF). The audit also examined the implementation of recommendations of VAGO's 2012 Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit.

I found that although the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has taken action to address our previous recommendations, it did not adequately address the identified issues.

My examination revealed that there were weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF which limits the department's ability to fully demonstrate the achievement of RGF objectives. I also found that Regional Development Victoria did not develop and implement an effective evaluation framework. The monitoring and reporting, which focused primarily on jobs and investment leveraged, is potentially misleading and not an accurate reflection of the achievements of the RGF. This continues to be a trend in performance reporting across government where Parliament and the community are not being reliably informed of the performance of various departments.

I have made recommendations to the department to improve its implementation, evaluation and reporting processes and bring them in line with better practice standards. Prompt action is required to address these issues in the new RJIF.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

16 September 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Andrew Evans—Engagement Leader Sheraz Siddiqui—Team Leader Simon Ho—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Kyley Daykin |

Regional Victoria is an important part of the state's economy. It is home to around a quarter of all Victorians, and significant population growth is expected in the years ahead. Regional and rural communities face a range of challenges, and there is no denying the importance of the government's role in supporting the regions to develop and prosper.

Regional Development Victoria (RDV) delivers large grant-based initiatives as part of its role as the state's lead agency for developing rural and regional Victoria. Over the past 13 years RDV has been managing grant programs that have allocated over $1.3 billion from at least three large initiatives. This audit focused on the Regional Growth Fund (RGF), which provided over $570 million in grants to local councils, business and other departments and agencies over the past four years.

In this audit, I examined whether the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has effectively addressed the recommendations from our 2012 audit, Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund. I also examined whether there were robust governance and oversight mechanisms in place under the RGF, whether intended outcomes were being achieved and whether the state is achieving value for its investments. Finally, I looked into how the department was applying lessons learned from our RGF audit to its new Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund.

While the department has acted to address many of the recommendations from the 2012 audit, in some areas it has not adequately addressed fundamental flaws. My audit found there were weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF, particularly around the transparency of application processes and in performance evaluation and reporting. There were also some weaknesses in governance, with independent assessment committees seemingly 'rubber stamping' projects for approval. These issues persist despite the department managing significant grant‑based programs for well over a decade. As a result, it was difficult to ascertain whether the best possible projects were funded under the RGF. This also brings into question whether the state achieved the best value for money for its investment in regional Victoria.

I am most concerned about the accuracy of reporting on jobs and investment leveraged—particularly reporting on job numbers as part of the department's Budget Paper measures.

For over a decade numerous VAGO audits have found significant weaknesses in the way departments measure and report on performance. As I highlighted in my 2014 report Public Sector Performance Measurement and Reporting, being transparent, and accurately measuring and effectively communicating performance to Parliament and the community, is critical for holding departments to account for their performance. Like the issues around reporting to Parliament highlighted in VAGO's 2012 report Managing Major Projects, it is doubtful that Parliament and the community are being accurately and reliably informed on the outcomes of the RGF. This audit, once again, highlights the need for departments to significantly improve their reporting to Parliament, and the governance around these processes.

The department has indicated that it will not change its reporting practices as they are in line with whole-of-government reporting. This 'head in the sand' approach will only perpetuate the provision of misleading and inaccurate reporting to government.

I am concerned and disappointed that the department does not fully acknowledge the significant issues raised and reflected in my recommendations. I urge the department to take action to fully address all of my recommendations and address the identified issues. While I note the department is applying some lessons learned to the new Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund, it must be vigilant in ensuring it maintains a renewed focus on evaluation and improved performance reporting, and on improving governance and transparency. The department's response does not provide me with any confidence that it will take all the necessary action to improve. I therefore intend to closely monitor the implementation of my recommendations, and will follow up with RDV and the department to ensure appropriate actions have been taken.

I want to thank the stakeholders who contributed to the audit by providing feedback and sharing their perspective.

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

September 2015

Audit Summary

Regional Victoria is an integral part of Victoria's economy. Approximately a quarter of Victorians live in regional areas where the population is projected to grow from 1.48 million to 2.91 million by 2036. The regional economy contributed $66.9 billion to the state economy in 2013–14, approximately 19.6 per cent. It also provided 21 per cent of the state's employment.

Regional and rural communities face a range of challenges including declining population in certain areas, fewer economic opportunities, issues with the development and maintenance of infrastructure, adverse environmental changes and the need for increased community participation. The current and previous Victorian governments have implemented a range of policies and initiatives aimed at driving regional development and dealing with these challenges.

The Regional Growth Fund (RGF) commenced in July 2011 and was an eight year, $1 billion commitment of the previous government to support regional development—it was initially funded with $500 million over four years. The RGF focused on creating jobs and leveraging investments in regional Victoria. It was also intended to improve community resilience, create regional leadership through community participation, and improve overall regional liveability.

In 2012 VAGO tabled the audit report Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund. While the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund (PVGF) had ceased at the time the report was released, the audit made recommendations in relation to its replacement, the RGF. These included:

- developing more robust business cases and processes to assess proposals to inform funding decisions

- developing clear and measureable outcomes

- developing a comprehensive evaluation framework supported by relevant and appropriate performance measures and targets

- implementing robust monitoring and reporting systems

- undertaking mid- and end-term evaluations with a focus on demonstrating the achievement of objectives and outcomes.

The RGF ceased in June 2015 following a change of government. It completed its first phase and allocated approximately $570 million during its operation. The newly established Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund (RJIF), which commenced in July 2015, is a $500 million fund replacing the RGF.

This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the RGF, the achievement of the intended outcomes and whether the lessons learnt from the RGF have been applied to the planning and implementation of the RJIF.

Conclusions

Weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF mean that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) cannot fully demonstrate that value for money and the goals and objectives of the RGF have all been achieved. These weaknesses include a lack of transparency in pre-application processes and fundamental flaws in performance evaluation and reporting.

Pre-application and assessment processes for major Economic Infrastructure Program projects of the RGF were subjective and lacked evidence upon which to base funding decisions, particularly as there was no documentation of the pre-application process. For other programs, including the Putting Locals First Program, there is better documentation with evidence that project proposals were assessed before full applications were submitted and assessed. The Local Government Infrastructure Program involved a formula based distribution of funds to local governments. There was also a general absence of sufficient benchmarks and targets for assessing applications and assuring that value for money is likely to be achieved.

Regional Development Victoria (RDV) did not implement an effective evaluation framework in the initial stages of the RGF, and undertook limited monitoring and reporting of all of the RGF's outcomes.

Monitoring and reporting activities primarily focused on jobs and investment leveraged. However, the figures reported are potentially misleading as they inflate the actual achievements of the RGF. Reported job numbers primarily relate to expected, rather than actual jobs created. Consequently, reported RGF figures do not provide an accurate picture of actual achievements.

These issues are not new to the department, and have persisted under the RGF because it did not adequately address our previous recommendations. Going forward, the department is applying the lessons learned to the design and implementation of the new RJIF. This includes developing a stronger evaluation framework with regular reviews, a greater focus on performance reporting, and collecting baseline data. However, given RJIF's recent implementation, it is too early to determine the effectiveness of these improvements.

Findings

Design of the Regional Growth Fund

RDV incorporated some better practice elements of grants management in the design of the RGF, including stakeholder engagement, grants processes, and governance and accountability. However elements relating to robust planning, a focus on outcomes, value for money, and probity and transparency were not adequately addressed.

Grant processes

With the exception of the Local Government Infrastructure Program, the RGF distributed funds using on a non-competing grant process. A non-competing grant process is one where applications are individually assessed against criteria without reference to any comparative applications. This process has the potential to increase uncertainty about how decisions are made because it reduces transparency. It is therefore important to establish and document clear and appropriate pre-application procedures.

RDV developed detailed criteria and guidance for RGF applicants. Prior to providing a formal application form, RDV held detailed discussions with potential applicants. For the Putting Locals First Program there is evidence of the pre-application process in the form of project proposals. However, for the major Economic Infrastructure Program, there is no evidence detailing these discussions. This has precluded an examination of whether the pre-application process was fair and appropriate.

Subjectivity of the assessment decisions

The RDV assessment process lacked consistency and included a degree of subjectivity.

Not all RGF programs had benchmarks and targets against which to assess funding applications. Where benchmarks and targets were available, RDV did not consistently apply them. In some cases funding was approved that exceeded benchmarks. However, RDV recorded reasons for exceeding the benchmarks.

In cases where all committee members did not support an assessment decision, their issues would be documented in the brief seeking ministerial consideration and approval. In all these instances, funding was approved. Although RDV generally provided detail on the concerns of the committee members in the brief to the minister, instances were noted where certain concerns were not reported.

Evaluation of the Regional Growth Fund

At the outset RDV did not have a robust evaluation framework in place for the RGF. Relevant and appropriate performance measures were not established until 18 months after the fund had commenced. Limited baseline data was collected and there was a general lack of benchmarks and targets for all RGF programs.

RDV invested significant resources and made efforts to have an evaluation of the RGF, however, it failed to do so. It did not undertake any program reviews despite the need for these being identified in its risk management plan. RDV has not yet carried out its final evaluation of the RGF—however, it is in the process of preparing for this.

Monitoring and reporting

RDV did not establish a robust set of performance measures at the start of the RGF. Although more detailed measures were subsequently developed, not all of the measures were monitored and reported on. RDV primarily focused on measures relating to jobs and investments, however, the reporting of jobs and investments is potentially misleading and does not present an accurate picture of the outcomes achieved. RDV now recognises the need for effective performance measures at the start of an initiative.

Accuracy of outcomes reported

In its budget paper and ministerial reporting, RDV reported the total number of jobs created by projects, regardless of the ratio of funding provided through the RGF versus the total project cost. Although there is still some ambiguity, RDV was clearer in presenting the information in its annual reports. In all reporting RDV also reported the gross number of jobs, without adjusting for factors such as jobs that would have been created without RGF support, or jobs that have been lost because of the project. A lack of program evaluation means RDV cannot demonstrate the achievement of the job numbers it claims to have created.

RDV used a similar method to report investment leveraged. It reported that approximately $1.5 billion in investments was leveraged from RGF's 1 800 projects. However, almost one-third of the $1.5 billion came from just six projects, which received just $7.7 million from the RGF out of their combined total cost of $525.9 million. That is less than 1.5 per cent of their total costs. Despite this, RDV reported that the $518.2 million leveraged from these six projects was completely attributable to the RGF.

Value for money

An absence of targets or benchmarks makes it difficult for assessment committees to decide whether the applications are providing value for money. RDV did not establish sufficient benchmarks for all programs. This lack of benchmarking and lack of documentation of the pre-application process makes it difficult to assess if the projects that were funded provided the best value for money.

Recommendations

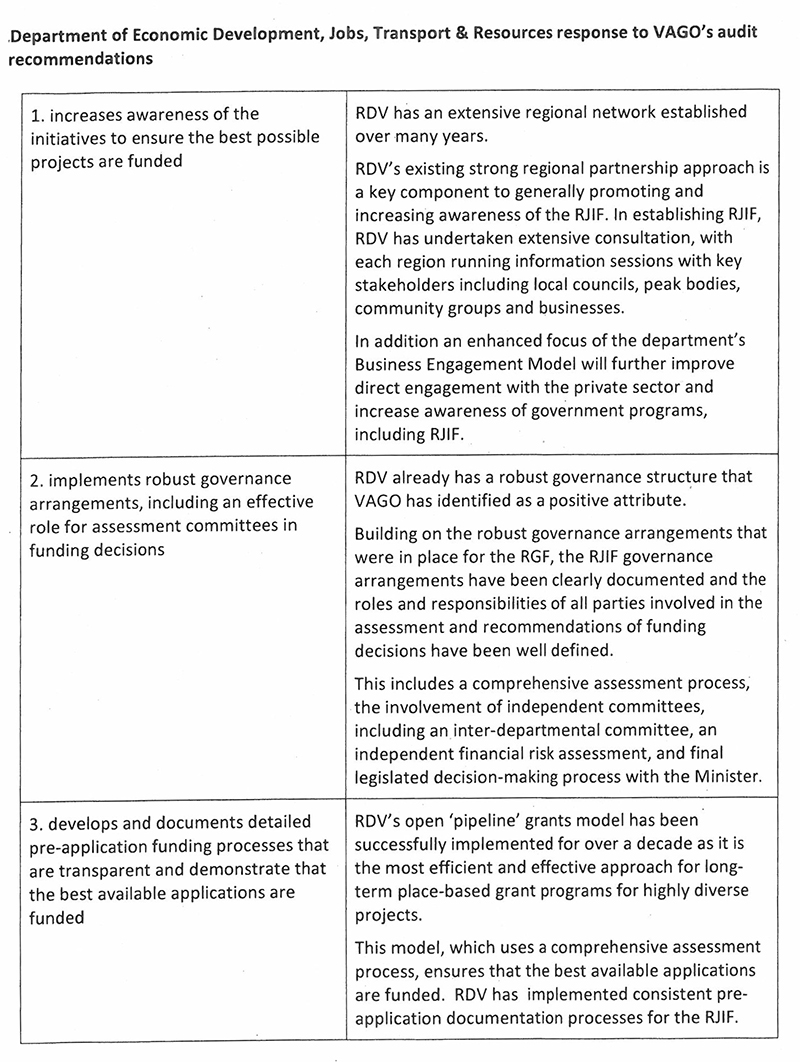

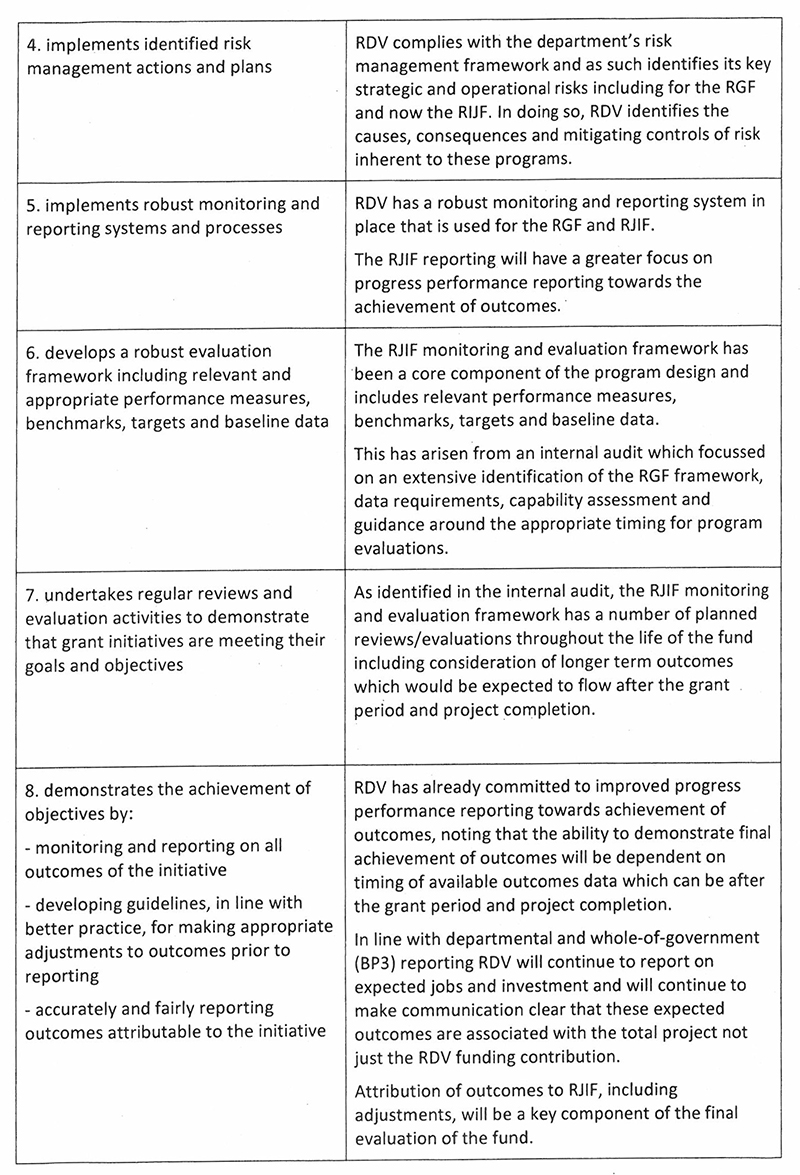

That, while developing and implementing the Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund and other future initiatives of a similar nature, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- increases awareness of the initiatives to ensure the best possible projects are funded

- implements robust governance arrangements, including an effective role for assessment committees in funding decisions

- develops and documents detailed pre-application funding processes that are transparent and demonstrate that the best available applications are funded

- implements identified risk management actions and plans

- implements robust monitoring and reporting systems and processes

- develops a robust evaluation framework including relevant and appropriate performance measures, benchmarks, targets and baseline data

- undertakes regular reviews and evaluation activities to demonstrate that grant initiatives are meeting their goals and objectives

- demonstrates the achievement of objectives by:

- monitoring and reporting on all outcomes of the initiative

- developing guidelines, in line with better practice, for making appropriate adjustments to outcomes prior to reporting

- accurately and fairly reporting outcomes attributable to the initiative

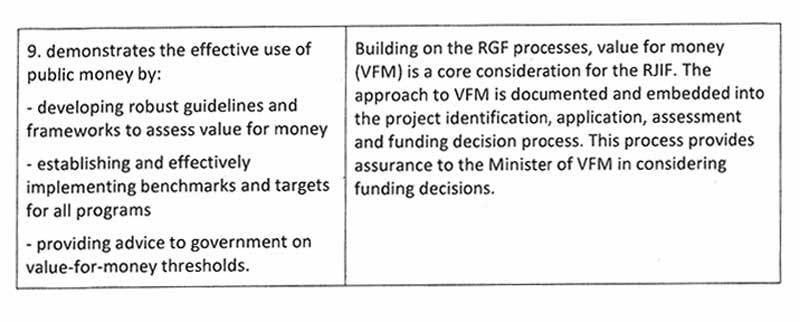

- demonstrates the effective use of public money by:

- developing robust guidelines and frameworks to assess value for money

- establishing and effectively implementing benchmarks and targets for all programs

- providing advice to government on value-for-money thresholds.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to the department and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 Regional development

1.1.1 Introduction

Regional Victoria is an integral part of Victoria's economy. Approximately a quarter of Victorians live in regional areas where the population is projected to grow from 1.48 million to 2.91 million by 2036. The regional economy contributed $66.9 billion to the state economy in 2013–14, around 19.6 per cent. It also provided 21 per cent of the state's employment.

Regional and rural communities face a range of challenges including declining population in some areas, fewer economic opportunities, issues with the development and maintenance of infrastructure, adverse environmental changes and the need for increased community participation.

1.1.2 Regional policy context

Regional Victoria is broken into five regions as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Breakdown of regional Victoria

Source: Regional Development Victoria (RDV).

A range of policies and plans guide development programs within these regions.

Regional Strategic Plans

Regional Strategic Plans (RSP) are prepared by community based committees including local government, community groups, and other stakeholders—including businesses. The RSPs identify the region's key issues, long-term plans and priorities to maximise economic and social development opportunities and manage future growth.

Regional Growth Plans

Regional Growth Plans build on the directions set out in RSPs by providing broad direction for land use and development. They are developed in a partnership between local government and state agencies and authorities through consultation with communities and key stakeholders.

Regional development initiatives

There has been a range of regional development initiatives focused on addressing the challenges facing regional Victoria over the past 15 years. These have primarily focused on developing infrastructure to drive economic development, and on empowering and developing regional communities. A brief time line of major initiatives is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Major regional development initiatives 1999–2015

|

Name of initiative |

Year started |

Year ended |

Amount allocated |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Regional Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) |

1999 |

2011 |

871 |

|

Provincial Victoria Growth Fund (PVGF) |

2005 |

2011 |

100 |

|

Regional Growth Fund (RGF) |

2011 |

2015 |

570 |

|

Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund (RGIF) |

2015 |

N/A |

500 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

Regional Infrastructure Development Fund

The RIDF was established in 1999 with an initial funding allocation of $181 million. Over 11 years $871 million was allocated through this fund. In addition to infrastructure, RIDF focused on capital works, transport, education, information and communications technology, and tourism facilities. RIDF was replaced by the RGF in 2011.

Provincial Victoria Growth Fund

Established in 2005, PVGF was a $100 million fund designed to complement RIDF and support activities designed to drive population, investment and business growth. PVGF contained multiple programs and projects supporting skilled migration, agriculture, business and recreational industries. PVGF was managed by a number of different government departments and agencies. PVGF funding ceased in June 2011.

Regional Growth Fund

RGF was established by the Regional Growth Fund Act 2011 as a trust fund in the Public Account. It was the then government's $1 billion commitment over eight years to drive regional development across Victoria. The first phase of the fund allocated $500 million in the first four years, and the remaining $500 million was to be allocated across 2015–19. An additional $70 million was allocated to the RGF, taking the total approved funding to approximately $570 million by 30 June 2015.

Approximately $231 million, or 46 per cent, of the initial RGF allocation of $500 million was for the election commitments of the previous government. A list of RGF election commitments is included in Appendix A.

RGF funding ceased on 30 June 2015 and a new $500 million RJIF came into operation on 1 July 2015. Both RGF and RJIF are examined in this audit.

Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund

The newly established RJIF is targeted towards creating jobs, supporting major infrastructure and building stronger communities. The RJIF has three components:

- the $250 million Regional Infrastructure Fund

- the $200 million Regional Jobs Fund

- the $50 million Stronger Regional Communities Plan.

Around $192 million, or 38 per cent, of the RJIF has been allocated to election commitments. The list of RJIF election commitments is also included in Appendix A.

1.1.3 Regional development funding

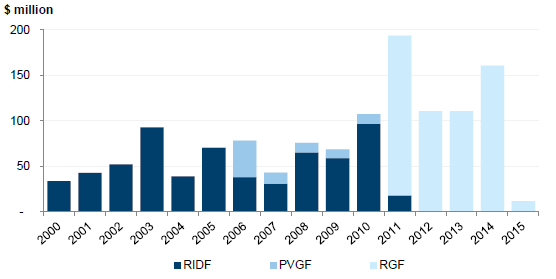

Figure 1C shows the approved grant amounts for regional development since 2000, which totals approximately $1.3 billion.

Figure 1C

Regional development approved grants 2000–15

Note: For the PVGF an approved grant amount of $300 000 is included in the 2011 grants.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

1.2 Overview of the Regional Growth Fund

1.2.1 Goals and objectives

The RGF had two long-term goals of 'developing a prosperous and thriving regional Victoria with more opportunities for regional Victorians' and 'improving the quality of life for regional Victorians'.

The RGF also had four objectives to accomplish its two goals:

- strengthening the economic base of regional Victoria

- facilitating the creation of jobs and improvement of career options for regional Victorians

- supporting the resilience and sustainability of communities in regional Victoria

- increasing the capacity of regional communities to drive development in their region.

1.2.2 Design and programs

The RGF was divided into strategic and local initiatives. The strategic initiatives were initially allocated $300 million while the local initiatives were allocated $200 million. The five broader programs under the RGF commenced in June 2011 and were targeted towards achieving the objectives of the RGF.

Economic Infrastructure Program

The aim of the Economic Infrastructure Program (EIP) was to provide support and funding for strategic infrastructure projects through a number of sub-programs. Both private and public sector entities were eligible for EIP funding. There were four sub-programs within the EIP:

- Growing and Sustaining Regional Industries and Jobs

- Transforming and Transitioning Local Economies

- Building Strategic Tourism and Cultural Assets

- Energy for the Regions.

Apart from the $123.7 million Energy for the Regions program, which was funded through a tendering process, EIP projects were evaluated by a two-stage assessment process, undertaken by RDV and the interdepartmental Regional Economic Infrastructure Committee (REIC).

A number of place-based programs were also administered through the EIP. These include:

- Geelong Advancement Fund

- Goulburn Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund

- Latrobe Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund

- Murray-Darling Basin Regional Economic Diversification Program.

Developing Stronger Regions Program

The Developing Stronger Regions Program (DSRP) provided support for studies to investigate the technical and economic viability of possible RDF projects. This included feasibility studies and business cases. The program's funding application process was similar to the EIP.

DSRP was open to both private sector and public sector entities.

Building Stronger Regions Program

The Building Stronger Regions Program (BSRP) provided resources to deliver most of the previous government's election commitments. These included the Gippsland Environment Fund, Local Solutions Year 12 Retention Initiative, Fire Ready Communities Program and a number of other smaller funds.

BSRP was open to public sector entities and educational institutions.

Local Government Infrastructure Program

The Local Government Infrastructure Program (LGIP) was a $100 million initiative that aimed to provide regional and rural councils with certainty to plan for, and build, new public infrastructure or to renew assets. Funding was determined by a formula based on a number of demographic factors including population.

Projects funded through the LGIP were nominated through councils' Forward Capital Work Plans, which are the councils' long-term infrastructure programs.

LGIP was only available to the local councils.

Putting Locals First Program

The Putting Locals First Program (PLFP) was a $100 million initiative designed to enable regional communities to deliver and address gaps in services and infrastructure in regional communities. PLFP project proposals were assessed by a two-stage assessment by RDV and Regional Development Australia (RDA) committees.

PLFP was open to both private and public sector entities.

Funding allocations

The RGF received $70 million in addition to its initial $500 million allocation as shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

RGF: Allocations and funding as at 30 June 2015, $ million

|

Program |

Initial allocation |

Final allocation |

Approved project funding |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strategic initiatives |

|||

|

EIP |

116 |

144.6 |

139.6 |

|

100 |

123.7 |

123.7 |

|

No initial allocation |

5.0 |

5.1 |

|

No initial allocation |

14.3 |

14.3 |

|

No initial allocation |

7.5 |

7.5 |

|

No initial allocation |

0 |

4.7 |

|

EIP subtotal |

216 |

295.1 |

294.9 |

|

DSRP |

12 |

11.5 |

8.2 |

|

BSRP |

72 |

65.0 |

66.1 |

|

Strategic initiatives subtotal |

300 |

371.6 |

369.2 |

|

Local initiatives |

|||

|

PLFP |

100 |

97.0 |

100.5 |

|

LGIP |

100 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Local initiatives subtotal |

200 |

197.0 |

200.5 |

|

Total(b) |

500 |

568.6 |

569.7 |

(a) The program had no initial allocation as it was started in 2014 in response to ongoing structural adjustment issues in the region. Final allocation is expected to be managed through future savings within the RGF.

(b) The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources has advised the excess approved funding of approximately $1.1 million is expected to be managed through future savings of the RGF.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

The initial RGF allocation of $500 million was supplemented by $52 million worth of savings and uncommitted funds from RIDF, an additional $11 million for the Geelong Advancement Fund, as well as interest earned on the fund annually. A portion of funds from DSRP and BSRP was reprioritised to support the establishment of place-based programs in response to emerging issues and demand throughout the course of the four-year fund.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 Regional Development Victoria

RDV is a statutory body established in 2002 and is part of the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

Prior to December 2014 the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources was the Department of State Development and Business Innovation, and prior to December 2013 it was the Department of Planning and Community Development.

RDV is the Victorian Government's lead agency for developing rural and regional Victoria. Its aim is to build stronger economies and communities through employment, investment and infrastructure.

RDV administered RGF through a trust fund arrangement.

1.3.2 Regional Policy Advisory Committee

The Regional Policy Advisory Committee (RPAC) was established in 2011 under the Regional Development Victoria Act 2002. The functions of RPAC included the provision of advice to the Minister for Regional and Rural Development on RGF strategic infrastructure projects that have statewide significance, or significance to rural and regional Victoria. RPAC was replaced by the Regional Development Advisory Committee in 2015.

1.3.3 Regional Development Australia committees

RDA committees were established under a cooperative arrangement between the state and federal governments. The five non-metropolitan Victorian RDA committees provide advice to the Minister for Regional and Rural Development on local priority projects, identified needs and government investment opportunities to be funded from the local initiatives of the RGF, including the PLFP.

1.3.4 Regional Economic Infrastructure Committee

REIC was an interdepartmental committee established to consider and assess applications received under a number of RGF infrastructure programs. It was responsible for making recommendations to the Minister for Regional and Rural Development about which infrastructure projects should be funded under the RGF.

REIC was chaired by the chief executive officer (CEO) of RDV and included representatives from:

- the Department of Premier of Cabinet

- the Department of Treasury and Finance

- the former Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure

- the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

- RDV.

REIC has been replaced by the Regional Infrastructure Development Committee. It will continue to be chaired by the CEO of RDV and will have representatives from the Department of Premier of Cabinet, the Department of Treasury and Finance, and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources as well as representatives from agencies and departmental divisions relevant to the applications being heard.

1.3.5 Department's Investment Committee

The Department's Investment Committee was an internal committee, within the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, that assessed business project proposals under the PLFP.

1.4 Previous VAGO audit

1.4.1 Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit

In 2012 VAGO tabled the audit report Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund. The audit found that PVGF had a number of issues including deficiencies relating to documentation and a lack of consistency in applying criteria to funding decisions. There was also no business case underpinning PVGF.

The audit also found that the monitoring and reporting processes, which were generally good, reported on outputs rather than outcomes. Further deficiencies in planning and evaluating meant RDV could not demonstrate that PVGF had achieved its objectives. The audit also found weaknesses in the risk management activities undertaken by the former Department of Planning and Community Development.

While PVGF had ceased at the time the report was released, the audit made recommendations in relation to the RGF. These included:

- developing more robust business cases and processes to assess proposals and inform funding decisions

- developing clear and measureable outcomes

- developing a comprehensive evaluation framework supported by relevant and appropriate performance measures and targets

- implementing robust monitoring and reporting systems

- undertaking mid- and end-term evaluations with a focus on demonstrating the achievement of objectives.

The department at the time—the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation—indicated that it had addressed these issues in its submission to the audit Responses to 2012–13 Performance Audit Recommendations.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the RGF. This included assessing the achievement of the intended outcomes and whether the lessons learned from the RGF have been applied to the planning and implementation of the RJIF.

To address this objective, the audit examined whether RDV:

- had effectively addressed recommendations from the Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit

- has robust governance and oversight mechanisms, the intended outcomes of the RGF and value for money is being achieved and lessons learned from RGF are being applied to the RJIF.

The audit considered recommendations of the 2012 PVGF audit and examined the achievement of regional development objectives as envisioned in the RGF.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit involved:

- review of RGF project documentation

- analysis of RDV data of RGF projects

- analysis of RDV internal and external reviews

- evaluation of RDV management responses to internal and external reviews

- interviews with key RDV staff.

The Australian National Audit Office issued a better practice guide for Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration in December 2013. The guide provides a framework for effectively administering a grants based program. VAGO has assessed the RGF against the key elements of this framework, among other better practice standards.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $350 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the design and implementation of the RGF

- Part 3 discusses the outcomes of the RGF.

2 Design and implementation of the Regional Growth Fund

At a glance

Background

The Regional Growth Fund (RGF) aimed to drive employment and economic growth, and strengthen the economic, social and environmental base of regional communities. Effective design and implementation is essential for delivering a large grant-based initiative of this kind. Funding processes and assessments should be transparent and equitable and there should be robust monitoring, reporting and evaluation.

Conclusion

There were weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF. Delays in developing an effective evaluation framework mean the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) is not able to demonstrate the achievement of RGF objectives and outcomes. Limited transparency around the pre-application process, combined with a lack of sufficient benchmarks and targets for key intended outcomes, makes it unclear whether the best available projects were funded and value for money was achieved. While the department has acted to address VAGO's previous recommendations, actions have not adequately addressed the issues.

Findings

- Pre-application processes were not well documented.

- A robust evaluation framework was not effectively developed and implemented.

- Performance measures were neither effectively developed nor monitored.

- There was a general lack of targets, benchmarks and baseline data for performance measures.

Recommendations

That, when designing and implementing future initiatives, the department:

- increases the level of documentation of funding processes, including pre-application processes and assessment decisions

- develops a robust evaluation framework including relevant and appropriate performance measures, benchmarks and targets

- undertakes regular reviews and evaluation activities to demonstrate that grant initiatives are meeting their goals and objectives.

2.1 Introduction

Robust planning and design is important for the successful implementation of a large grant-based initiative. Initiatives should be soundly based, have a clear rationale, provide value for money, have effective governance mechanisms, identify risks and implement effective risk management strategies. Probity and transparency should be entrenched throughout the design and implementation of the initiatives. An effective grants initiative should include relevant and appropriate performance measures and have an effective monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework to demonstrate the achievement of objectives and intended outcomes.

Our 2012 audit, Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund, recommended that Regional Development Victoria (RDV) apply the lessons learned from the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund to the Regional Growth Fund (RGF). Key recommendations included:

- ensuring the fund is soundly based

- developing a comprehensive evaluation framework with relevant and appropriate performance targets

- undertaking outcome-based evaluations

- developing a risk management framework

- implementing appropriate record keeping and document management systems.

2.2 Conclusion

There were weaknesses in the design and implementation of the RGF. Delays in developing an effective evaluation framework that includes robust performance measures, and ineffective implementation of the framework, as well as limited monitoring and reporting activities mean the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) is not able to fully demonstrate the achievement of RGF objectives and outcomes to date. RDV identified effective risk management strategies but these were not implemented. This increased the risks to achieving RGF's objectives.

RGF's funding assessment decisions were not transparent, particularly for the major infrastructure projects that involved a degree of subjectivity. Pre-application and assessment documentation was not robust, and there was no evidence around how proposals were short-listed.

The Putting Locals First Program (PLFP) component was more transparent in its pre-application process with documents available for projects that did not proceed to full application stage. Almost all the applications that were assessed were recommended for funding by the oversight committees and eventually funded. The department advised this is an expected outcome in an effective pipeline grants model, which was used for most programs. However, it is not clear how it can be determined that the application process was effectively managed without robust evidence of the pre-application process.

This, combined with a lack of benchmarks and targets for key outcomes, provides limited assurance that the best available projects were funded and that value for money was achieved. While the department has acted to address VAGO's previous recommendations, in most cases actions have not adequately addressed the issues.

2.3 Development of the Regional Growth Fund

A major initiative like the RGF should be underpinned by a business case that demonstrates the need for the initiative, consideration of alternative options and effective governance and risk management frameworks. It should also include a well-developed evaluation framework to support monitoring and reporting on the achievement of objectives and intended outcomes.

2.3.1 Business cases and the Policy Context and Operational Model

RDV developed a detailed Policy Context and Operational Model (the Model) in April 2011 to guide the implementation of the RGF. When read in conjunction with the business case—which does not contain sufficient information—it provides a reasonable basis for the RGF as a whole. RDV has advised that it followed whole-of-government guidelines for the preparation of short form business cases for election commitments. However, this should not preclude it from developing robust business cases to fully inform government of the available options.

The Model provides more details of the need and rationale for the RGF and outlines the challenges for regional Victoria, such as structural adjustment to industry and social disadvantage. It also provides the operational guidelines for the RGF including:

- fund design, and details on the strategic and local initiatives streams of the fund

- a risk management strategy that identifies the risks to the achievement of RGF objectives

- a governance framework that identifies the various committees and their roles in the overall governance of the RGF

- an evaluation framework that identifies performance measures and monitoring and reporting activities that would help demonstrate the achievement of RGF objectives.

However, the initial evaluation framework and performance measures required significant revision 18 months after the RGF commenced. This is discussed further in Section 2.6.

2.3.2 Pipeline funding model

RDV has adopted an open-ended 'pipeline' grants model for most RGF programs. It believes this is the most efficient and effective approach for long-term place-based grant programs that support highly heterogeneous projects and programs seeking to address complex, higher risk, inter-related economic and social policy objectives. The projects funded by the RGF vary substantially in size, nature, proponents, timing, risks, costs and benefits.

RDV advised that the context in which this model operates is through long-term deep-seated relationships with regional businesses and communities, and a strong track record of working with stakeholders to build shared understanding—for example on relative competitive advantages and drivers of growth—and to work iteratively to develop and support the investments that make a difference. Applications are required to address how the proposal reflects Regional Strategic Plans, which identify regional priority projects. RDV believes this is a highly transparent model that is informed by shared information within a regional context and in which value for money is assessed openly by regional leaders.

2.3.3 Assessment of Regional Growth Fund planning and design against better practice

The Australian National Audit Office's (ANAO) better practice guide, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration identifies seven key principles of grants administration. Our assessment of the RGF planning and design against these principles is shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Planning and design assessment against ANAO framework

|

Key principle |

Evidenced in RGF planning |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Robust planning and design |

Partly |

The business cases were not robust. The Model included more detail regarding RGF planning and design. However, key elements, including the evaluation framework, were not sufficiently developed and required significant revision. |

|

Collaboration and partnership—with grant recipients and other relevant stakeholders |

✔ |

There is evidence of both internal and external stakeholder input in RGF planning and design. Projects proposed by Commonwealth and state governments, local councils and the private sector were funded, indicating a reasonable degree of collaboration and partnership. |

|

Proportionality—program design features and administrative processes address complexity of grant program |

✔ |

The RGF had a detailed program design that provided for a more focused approach for specific programs. It was divided into five programs with different objectives, guidelines and administrative processes. Separate teams administered programs of a different nature. |

|

An outcomes orientation |

Partly |

The over-arching goals and objectives of the RGF reflect an outcomes orientation. However, limited performance measures were developed at the start of the RGF to monitor the stated outcomes. |

|

Achieving value with public money |

Partly |

Achieving value for money should be 'a prime consideration in all aspects of grants administration'. RDV believes that 'value for money considerations are embedded and operationalised throughout the program'. However, our assessment indicates there is no clear framework for achieving value for money in the RGF program design. The program guidelines have a criterion of maximising value to the state, but do not clarify how this will be achieved. Limited consideration of value for money was evident at the implementation stage. |

|

Governance and accountability |

✔ |

The Model identified a well-developed governance and accountability framework, which included several oversight committees. |

|

Probity and transparency |

Partly |

Decisions relating to grant activities should be impartial, appropriately documented and publicly defensible. There is limited reference to probity and transparency in the RGF planning and design stating that 'the Fund will apply integrity and transparency in its decision-making, with the results of funding decisions and the spread of allocations publicly available'. The pre-application process was not documented for the Economic Infrastructure Program (EIP), which provides limited transparency of the funding process. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on ANAO's better practice guide, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration.

2.4 Governance

Good program governance should provide transparency and confidence in decision-making, which should be able to withstand all forms of public scrutiny. An effective governance framework should also provide clarity of roles and responsibilities and include adequate consideration for various stakeholder interests.

2.4.1 Grant processes

A 'pipeline'—open-ended, non-competing—grants model was used for the majority of RGF programs except the $100 million Local Government Infrastructure Program (LGIP) where RDV adopted a formula-based grant, which was government policy. In a non-competing grant process applications are assessed individually against the selection criteria without reference to the comparative merits of other applications.

The application and funding process is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Application and funding process for RGF funding

|

Stage |

Comments |

|---|---|

|

Initial—information provided |

|

|

Pre-application |

|

|

Assessment and funding |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

Although non-competing grants are an acceptable approach for grants funding, the ANAO better practice guidelines state that it 'increases uncertainty, reduces transparency and perceived equity and may disadvantage some potential grant recipients'. The guidelines also identify circumstances in which alternative application processes are appropriate. RDV's pipeline model fits within ANAO's alternative method of non-competitive grants model.

However, the guidelines state that when this approach is used 'it will be important to establish mechanisms that will provide appropriate transparency in regard to the pre-application processes undertaken'. RDV believes it provides transparency from the full cycle of regional planning through to final project assessment. However, lack of documentation of the pre-application process means RDV cannot demonstrate this for the major infrastructure component.

RDV developed detailed guidelines for various RGF programs. The published assessment criteria addressed the objectives of the RGF and provided applicants with appropriate information to determine if their projects aligned with the relevant RGF funding criteria.

RDV advised that it held detailed discussions with 'potential funding applicants' prior to providing them with application forms for their formal application. However, for the EIP there is no documentation available recording these discussions. This precluded an examination of whether the pre-application process was fair and transparent. RDV has provided a summary of events that took place in the pre-application process for some projects that were funded. However, this summary is not equivalent to a record of the content of discussions.

RDV believes making application forms widely available would lead to a high proportion of ineligible proposals, and subject potential applicants and RDV to unnecessary administrative burden. However, robust design and guidance around the application process could address this concern.

Need for awareness

A non-competing grant process should ideally include wide awareness of the availability of grants. RDV believes it has strong relationships with regional businesses and communities and a strong track record of working with stakeholders to develop and support investments that make a difference.

A 2013 internal review that RDV conducted to inform the design of the second phase of the RGF, recommended taking steps to increase awareness of the RGF and its programs. A 2013 external evaluation of RGF governance and administration found that there was limited awareness of the RGF. RDV advised that post the external evaluation it was transferred into the former Department of State Development and Business Innovation, where a well-established Business Engagement Model operated and asserted that this concern was addressed.

In July 2015, the government undertook the Regional Economic Development and Services Review aimed at improving service delivery in regional Victoria. Submissions for the review also include feedback indicating the need for increasing awareness.

- 'The fund is open to more than just Local Government Authorities, but there does not appear to be great awareness of this.'

Limited awareness of RGF's non-competing grants process increases the risk that it will not fund the best possible applications.

2.4.2 Assessment decisions

Nearly all applications received for the RGF were ultimately approved for funding, as shown in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

Number of applications submitted and approved

|

Program |

Value |

Expression of interest / project proposals |

Full applications |

Approved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EIP—including Building Stronger Regions Program |

205.7 |

N/A |

66 |

60 |

|

Energy for the Regions |

53.7 |

N/A |

8 |

8 |

|

Energy for the Regions Tender |

70.0 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

PLFP |

100.5 |

1 062 |

803 |

799 |

|

Latrobe Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund(a) (b) |

14.3 |

N/A |

13 |

13 |

|

Geelong Advancement Fund |

7.5 |

23 |

4 |

4 |

|

Goulbourn Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund(a) |

5.1 |

N/A |

3 |

3 |

|

Murray Darling Basin Regional Economic Diversification Program |

4.7 |

N/A |

6 |

5 |

|

Developing Stronger Regions Program |

8.2 |

N/A |

27 |

26 |

|

Total |

469.7 |

1 089 |

933 |

919 |

(a) Projects that cost more than $250 000.

(b) The Latrobe Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund received 128 enquiries confirming eligibility. RDV has maintained a list of these enquiries.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

For PLFP, the guidelines stated that after an initial discussion the potential applicant should provide a project proposal as part of the pre-application process. This resembled an expression of interest process. Once RDV had assessed the project proposal, it would provide the applicant with an application form for their formal application.

RDV received 1 612 enquiries for the PLFP. Of these, 1 062 submitted a formal project proposal to RDV, and once assessed, only 803 were invited to formally apply. Only four of the submitted applications did not receive funding. This was a better example of the department documenting its pre-application processes.

File reviews

We reviewed a random selection of 39 files from all the RGF programs, excluding the LGIP. This program was not included as it was a formula-based funding program providing grants to all regional councils.

For the EIP we found that the funding assessment process was not robust, lacked consistency and included a degree of subjectivity. Lack of documentation, of the pre-application process of the EIP, means that it was difficult to ascertain if RDV funded the best available projects. The PLFP process was more objective with a clear rating of the overall application. In the files reviewed for the PLFP, only one exception to the established benchmark was made for which a robust rationale—bushfire emergency—was properly documented.

Key observations from file reviews are shown in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

Detailed observations from sample file reviews

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on sample project files provided by RDV.

2.4.3 Oversight

Four committees had a role in the overall governance and oversight of the RGF, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

RGF committees

|

Committee |

Function |

|---|---|

|

Regional Economic Infrastructure Committee (REIC) |

An interdepartmental committee that had representation from other departments, including Department of Treasury and Finance, and Department of Premier and Cabinet. This committee made recommendations to the Minister of Regional and Rural Development for infrastructure-related projects. |

|

Regional Policy Advisory Committee |

An independent committee providing advice to the minister on regional priorities. This committee provided strategic advice to the minister and was not involved in funding decisions. |

|

Regional Development Australia (RDA) committees |

Independent committees drawing membership from local councils, businesses and communities that made recommendations for the PLFP. |

|

Department's Investment Committee |

An internal committee that assessed business project proposals under the PLFP. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

Sample review of committee decisions

REIC and RDA committees were provided with funding applications along with RDV's assessment to consider and make recommendations to the minister. A review of 13 REIC meeting minutes and 15 RDA meeting minutes identified that:

- of the 35 projects considered by REIC, 34 were recommended for funding—one decision was deferred

- of the 66 projects considered, 62 were recommended by the RDA—three were deferred, one was not supported.

The committees supported and recommended almost all applications and assessments for funding to the minister. A December 2012 brief to the then Deputy Premier and the then Minister of Regional and Rural Development noted that a 'concern has been expressed by some RDA committee members that their role is largely to 'rubber stamp' recommendations prepared by the department'. Following this RDV provided more information to the RDA committees, including complete project assessments and proposal outcomes. RDV has advised that no additional issues were raised by the RDA committees subsequent to this increase in the provision of information.

2.5 Risk management

Effective risk management involves the systematic identification, analysis, treatment and allocation of risks, both in relation to the overall design of a grant process and in the assessment and administration of individual grants.

In response to the Managing the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit, RDV developed a new risk management framework, a risk treatment plan template, and a risk register. The risk management framework incorporates most elements of better practice, with the risk register being comprehensive and regularly updated. The risk register assesses risks and identifies follow up actions. Relevant actions were undertaken in most cases, however, not all issues were adequately addressed.

While planning RGF risk management activities, RDV recognised that the broad objectives of RGF could lead to difficulties in measuring outcomes. To address this, RDV planned a number of actions, including:

- building the evaluation capacity of the staff responsible for delivering RGF programs

- developing reporting mechanisms to inform the public and Parliament about the performance and outcomes of the RGF

- robustly assessing all project and program applications

- undertaking an interim evaluation of a sample of RGF programs within the first two years to assess their effectiveness and realisation of RGF objectives.

RDV did not carry out the planned interim evaluations. A 2015 internal review recommended that RDV undertake several short formative evaluations over the course of a program's implementation. RDV advised that it did not consider interim evaluations were necessary because of the formative evaluation it conducted of the RGF in 2012 and 2013. Further, RDV reported on the RGF through normal Cabinet processes, publicly through its annual report and to Parliament through standard processes such as the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee. However, reporting to the minister was restricted to project details such as the number and type of projects and level of funding. The annual report presented case studies but did not describe its performance against targets.

RDV therefore failed to develop and implement appropriate reporting mechanisms regarding the performance and outcomes of the RGF.

2.6 Evaluation activities

A well-planned and executed evaluation provides timely evidence on the efficiency and effectiveness of programs. This helps strengthen public confidence in the use of public money. Evaluation should be used in conjunction with supporting activities such as:

- sample program reviews—used throughout the life of a program, particularly when there is insufficient information to conduct a final evaluation

- monitoring and reporting—robust and regular monitoring of identified performance measures and regular comparisons with identified benchmarks and targets that provide information for robust evaluation

- ongoing research—continuously seeking feedback relating to the effectiveness of a program helps support the overall evaluation of the program.

2.6.1 Evaluation framework

An evaluation framework should be developed prior to the commencement of a program. It should include well-defined logic that connects the overall goals of the program to the expected outcomes through a series of strategic action areas. The framework should also have relevant and appropriate performance measures and related benchmarks and targets underpinned by appropriate baseline data. Regular evaluation activities should be planned and undertaken during the life of the program. This will ensure robust evidence is collected at regular intervals and provide assurance that the program is on track to achieve its objectives. Regular reviews would also provide opportunities to improve the framework over the life of the program.

The original RGF evaluation framework was revised in March 2012 and then again in January 2013, as shown in Figure 2F.

Figure 2F

Development of RGF evaluation framework

|

Original framework July 2011 |

First revision March 2012 |

Second revision January 2013 |

|---|---|---|

|

Provided an overview of the RGF. |

Further details of RGF programs were added. |

Substantial overall changes were made. |

|

Fund Evaluation Program Logic Model, outcomes, outputs and four strategic action areas (SAA) were identified. |

Outcomes were further expanded into short-, medium- and long-term outcomes. SAAs were merged into outcomes and outputs. |

A list of 12 SAAs was developed, including three for each objective. |

|

RGF evaluation questions were framed. |

Evaluation questions were reworked providing substantially more detail and context. |

A more organised structure was introduced. One key evaluation question for each SAA was identified. |

|

Reporting, monitoring and evaluation activities were identified. |

More details were added on the evaluation subject, purpose, audience, phases, resources available, scope and the overall context of evaluation. |

No substantial changes for monitoring and evaluation, except RGF annual interim evaluations were removed. |

|

Fifteen performance measures were identified. |

Performance measures were expanded to a list of 20. |

Significant revision in the list of performance measures with 68 unique performance measures identified. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

Relevant and appropriate performance measures were not established at the outset of the RGF. Limited baseline data was collected and an insufficient number of benchmarks and targets were included for all RGF programs. The revised evaluation framework of January 2013 set out a more robust program logic, with objectives clearly linked to outcomes. A comprehensive list of performance measures was also developed. However, a lack of monitoring and reporting on the performance measures meant that RDV did not effectively implement the revised framework.

RDV did not undertake any interim evaluations of a sample of RGF programs despite the need for these being identified in its risk management plan. The planned interim evaluations were not undertaken and the external evaluation was seen as a replacement.

In December 2014, RDV's Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group observed:

- 'RGF framework could be clearer.'

- 'It is evident there is work to be done in retrospectively designing these (outcome logic model and a monitoring and evaluation framework) documents for the RGF as well as for the future [Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund] work.'

2.6.2 Regional Growth Fund evaluations

RDV engaged a consultant to undertake formative and mid-term evaluations of the RGF. In October 2013, RDV amended the contract to split the mid-term evaluation into two parts including:

- governance and administration evaluation

- social and economic impact evaluation.

RDV did not accept the social and economic evaluation report due to what it considered its 'poor quality' and the contract was terminated in November 2014. RDV paid approximately $322 000 of the $450 000 to the contractor as the final settlement. RDV therefore does not yet have an outcomes-based evaluation, which was a key recommendation of the Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit. RDV has advised it is currently preparing for a full-term evaluation.

Formative evaluation

The formative evaluation, completed in January 2013, was to review the RGF evaluation framework, provide recommendations about timely, efficient and effective data collection, produce a whole-of-RGF evaluation plan, and report on the initial RGF implementation and program development activities.

The formative evaluation recommendations included improving the evaluation framework, the performance measures, and data collection practices. RDV implemented some of these recommendations, including updating its evaluation framework and performance measures.

Governance and administration evaluation

The consultant completed this evaluation in February 2014 and recommended ensuring robust planning for future initiatives. The evaluation recommended having clearly articulated frameworks for programs, devolving powers for minor decisions, increasing awareness of available funding, and engaging with local business and community networks. The evaluation also recommended assigning weights to assessment criteria of various programs.

RDV did not accept the recommendations relating to assigning weights to various assessment criteria and devolving minor decision-making powers to regional directors. RDV has advised it did not accept the recommendation to devolve powers, as all grant approvals require the authorisation of the minister. The recommendation to use weighting was not accepted in the EIP as each criterion is as important as the other. However, it is unclear why RDV could not have assigned equal weights to all criteria to confirm this understanding to potential applicants.

Social and economic impact evaluation

The consultant completed this analysis in April 2014. The evaluation used a program logic analysis, a cost-benefit analysis and a macroeconomic analysis to assess the impact of RGF activities. The evaluation concluded that the RGF was achieving its short-term outcomes and was progressing towards the longer-term outcomes in line with the four objectives of the RGF. As previously stated, RDV did not accept this report.

Comments

RDV put in a significant amount of resources and effort to have an outcome-based evaluation of the RGF. However, at the outset RDV did not have a robust evaluation framework set up for the RGF. Although the evaluation framework was significantly revised, it did not monitor and collect appropriate data. RDV relied heavily on the consultant to collect data and undertake its evaluation activities and had a limited focus on self-evaluation. The evaluation process was not well managed and RDV's oversight of the process was not effective. This resulted in work that was not acceptable to RDV and means public funds were not used in an effective and economical manner.

RDV established limited baseline data and an insufficient set of benchmarks and targets, which have added to the difficulties in undertaking a robust evaluation. A 2008 Regional Infrastructure Development Fund external evaluation found that there was a lack of baseline data, which 'either was not available' or 'had not been measured'. This suggests that a lack of baseline data has been a persistent issue for RDV.

RDV is now preparing for a final evaluation of the RGF. In response to an April 2015 internal review recommendation, RDV has committed to 'include a range of reviews/ evaluations throughout the life of the [Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund]'. This is evident from the draft evaluation framework of the Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund.

The Monitoring Working Group, since renamed the Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group, was responsible for the RGF monthly updates to RDV's Monitoring and Evaluation Committee. RDV did not document any minutes of the Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group prior to December 2014. The minutes of the two recent meetings outline how crucial a role the Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group can play by assigning responsibilities, following up actions and conducting a stocktake of various ongoing evaluation activities.

2.7 Performance monitoring and reporting

Performance reports should be:

- comprehensive—performance indicators should be relevant to all critical aspects of objectives, which in turn should be clearly expressed and measurable

- balanced—should have a balanced suite of indicators that cover all important dimensions of performance such as efficiency, quality and outcomes

- appropriate—indicators should be reported with appropriate context such as targets, trends and explanations to enable the proper interpretation of results and for meaningful conclusions about performance to be drawn.

Effective performance measures enable organisations to monitor and report on their achievements. The measures should be developed prior to starting any project. Our Management of the Provincial Victoria Growth Fund audit recommended that relevant and appropriate performance measures and targets should be developed for the RGF.

2.7.1 Performance measures

An assessment of the RGF performance measures is shown in Figure 2G.

Figure 2G

Assessment of Key Performance Measures (KPM)

|

Identified performance measures |

VAGO's comments |

|---|---|

|

July 2011 RGF formally commenced operations and 15 KPMs were developed |

|

|

March 2012 List of KPMs revised to 20 |

|

|

January 2013 List of 68 KPMs developed |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by RDV.

RDV has primarily focused on measures relating to jobs and investment while other measures are not robustly monitored and reported on. RDV now recognises the need for effective performance measures at the start of the program as observed by its Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group:

- 'RDV can be better at measuring outcomes—it churns out outputs; we need more data on impact/outcome—long-term versus short-term outcomes.'

- 'It is important to identify KPMs at the beginning of the project including qualitative outcomes.'

2.7.2 Monitoring

The RGF has been impacted by machinery-of-government changes. In December 2013, the Department of Planning and Community Development became the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation, which became the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources in December 2014.

The first transition changed RDV's grants management recording system, replacing e‑Grants with the Global Engagement Management System (GEMS) which improved RDV's grants record management system capability. GEMS records 'live data' for certain key statistics. It allows RDV to extract overview data about the progress of the RGF, its programs and individual projects. This data includes milestones, approval statuses, funding spent and leveraged as well as various outcome data.

The department has monitored project details and progress using GEMS and has focused its monitoring on jobs and investment leveraged as key outcomes. The monitoring of other outcomes is not effectively undertaken. Although in existence, there is no evidence of the functioning or effectiveness of the Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group as no meeting minutes were documented prior to December 2014.

2.7.3 Reporting

RDV undertakes ongoing monitoring at the project level to ensure projects are delivering their agreed outputs. RDV provided the minister with reporting of outputs at the individual project and fund level. RDV also assesses final project completion reports to evaluate project outcomes prior to final acquittal of milestone payments.

However, reporting of performance outcomes achieved to date at the fund level is poor, including performance reporting to the minister. RDV has primarily reported on the number of projects and level of funding allocated from various RGF programs. The reports also included numbers of jobs created and the amount of investment leveraged. RDV accepted a finding of the April 2015 internal review that highlighted the lack of performance reporting for RGF.

RDV provides key highlights of its achievements in its annual report, including information about jobs created and investment leveraged. The type and nature of projects funded are also part of the annual report. However, there is no consolidated reporting of the overall achievements of the RGF.

RDV advised that it is addressing the issue of the lack of baseline data. The Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund evaluation framework now includes collecting baseline data at the start. General economic data is also available through RDV's online Information Portal. RDV advised that it will use this larger body of work as the baseline data for the RGF final evaluation.

Part 3.4 of this report discusses RGF reporting, especially with reference to jobs and investments, in more detail.

Recommendations

That, while developing and implementing the Regional Jobs and Infrastructure Fund and other future initiatives of a similar nature, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- increases awareness of the initiatives to ensure the best possible projects are funded

- implements robust governance arrangements, including an effective role for assessment committees in funding decisions

- develops and documents detailed pre-application funding processes that are transparent and demonstrate that the best available applications are funded

- implements identified risk management actions and plans

- implements robust monitoring and reporting systems and processes

- develops a robust evaluation framework including relevant and appropriate performance measures, benchmarks, targets and baseline data

- undertakes regular reviews and evaluation activities to demonstrate that grant initiatives are meeting their goals and objectives.

3 Outcomes of the Regional Growth Fund

At a glance

Background

The Regional Growth Fund (RGF) provided funding of around $570 million to more than 1 800 projects over four years. The RGF aimed to drive economic development, improve career opportunities, create jobs, support sustainability and increase the capacity of regional communities.

Conclusion

Although a significant number of outcomes were expected from the RGF, the Department of Economic Development Jobs Transport & Resources' (the department) monitoring and reporting activities primarily focused on jobs created and investment leveraged. There is limited assurance around the accuracy of the reported job numbers and investment leveraged as a result of the RGF. Moreover, the department cannot fully demonstrate it has achieved value for money through the projects funded by the RGF.

Findings

- Most reported job and investment outcomes are inflated and not an accurate reflection of the RGF contribution.

- The department did not report on all outcomes of the RGF.

- The department did not have benchmarks and targets for all programs. In cases where these were available these were not consistently applied.

Recommendations

That, when designing and implementing future programs, the department:

- ensures effective monitoring and reporting on all outcomes

- establishes benchmarks and targets to provide assurance that value for money is being achieved