Service Victoria—Digital Delivery of Government Services

Snapshot

Has digital delivery of government services improved customer experiences and reduced costs?

Why this audit is important

As Victoria's population grows, so do customer interactions with public services.

Digitising services can help to reduce demand pressure, save money, and improve customer satisfaction.

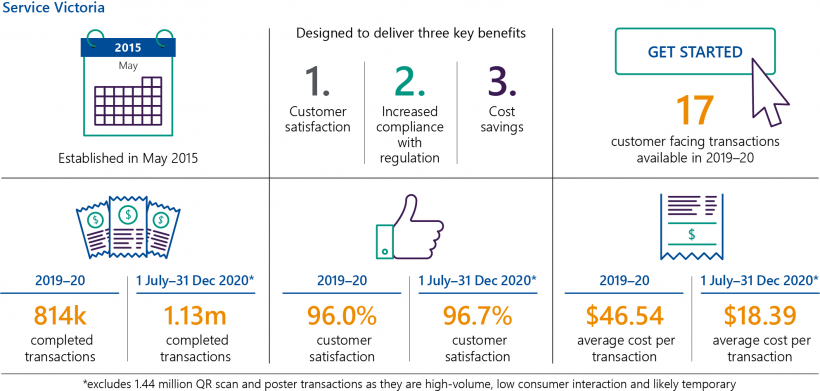

In 2015, the government established Service Victoria (SV) to seize this opportunity and deliver cross-government reform.

The impact of COVID-19 and the need to make services available digitally further highlight the importance of this change.

Who we examined

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), including its administrative office SV.

What we examined

We examined:

- the implementation of SV and DPC’s oversight of it.

- the benefits SV is delivering.

What we concluded

While SV has improved customer experience through the services it delivers, it has not reduced transaction costs as intended.

SV has delivered a repeatable and scalable digital platform and technology solution. SV has shown the benefit to government from this platform, such as through quickly rolling out COVID-19-related transactions including venue check-ins using QR code scans.

However, SV has not delivered the wide range of transactions envisaged at its outset. With the exception of recent COVID 19 related transactions; the types and low volumes of transactions that SV delivers mean it has not realised its objective of reducing the costs of existing government transactions and improving compliance with regulation.

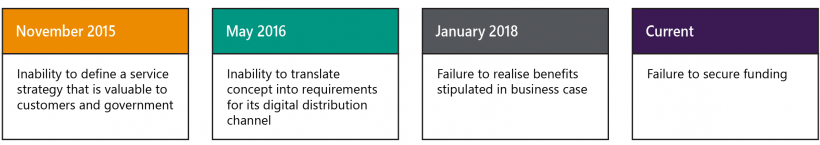

SV's implementation was hampered by a poor business case and inadequate stakeholder and risk management, exacerbated by the lack of a strong mandate. DPC and SV missed several opportunities to address these issues.

This has meant that SV has fallen well short of its ambition to achieve whole-of-government digital transaction reform in its first five years.

What we recommended

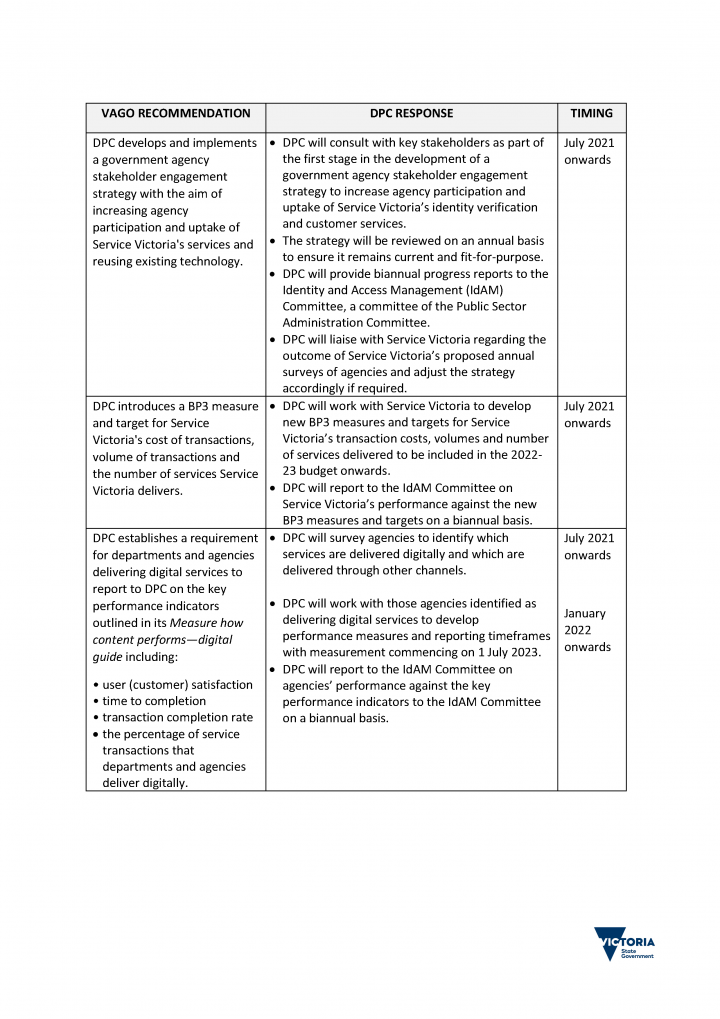

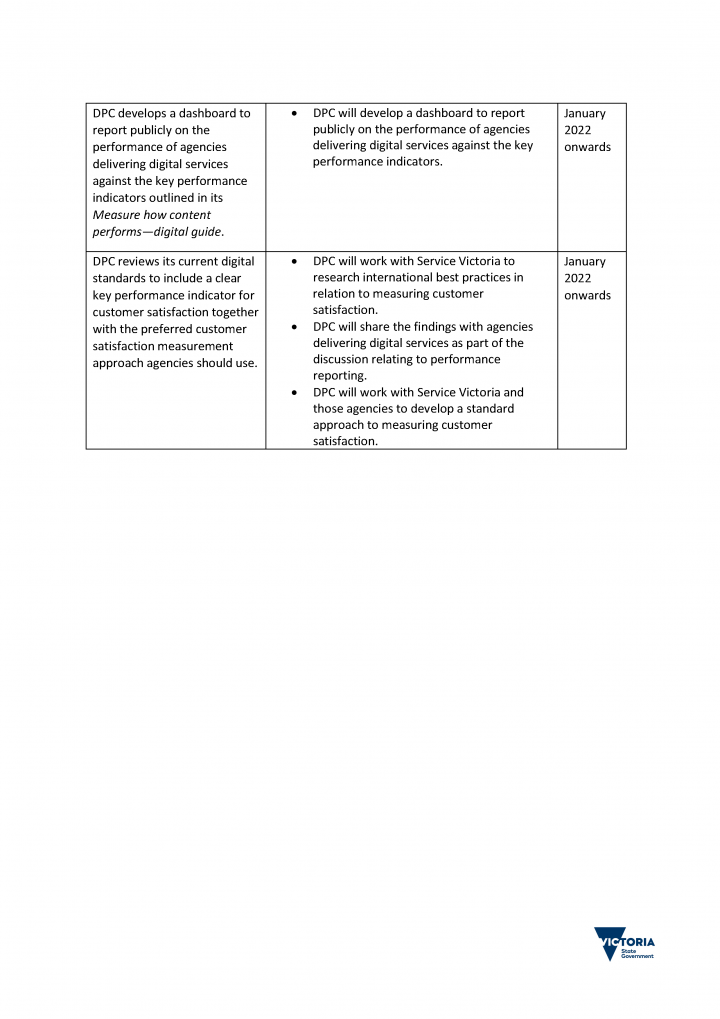

We made five recommendations to DPC. Four recommendations relate to improving its reporting and guidance on transactional services and one relates to introducing a stakeholder engagement strategy.

We also made five recommendations to SV. Four recommendations relate to improving SV’s transaction baselines and benefits reporting and one relates to data collection to enable SV to understand agency feedback on its performance.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Transaction reform

Most people want to be able to complete transactions, such as pay bills, apply for services or update their details, anywhere and at any time.

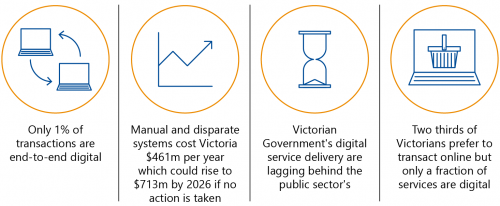

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) estimated that the Victorian Government conducted over 55 million transactions with customers in 2015, with only 1 per cent being fully digital. Most transactions were face-to-face, or via phone or mail.

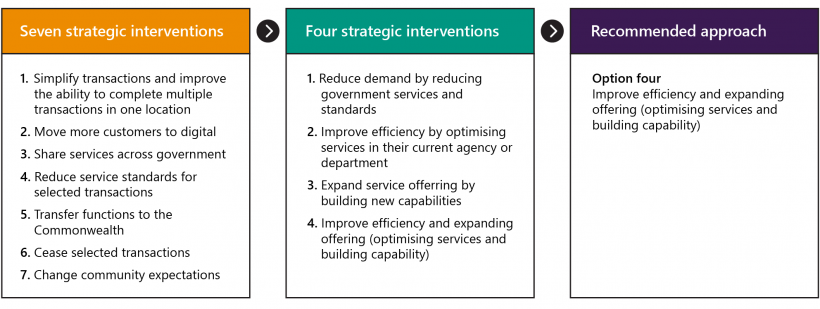

Recognising that such transactions are costly to government and often not preferred by customers, DPC and the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation commissioned external consultants to examine the case for reform.

DPC stated in its 2015 Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of Victorian Government transactional services full business case (the Reform Program business case) that it cost government $461 million per year to deliver transaction services across six departments and seven major agencies. It predicted that without changes, by 2026, this would increase to $713 million per year.

DPC, in its Reform Program business case, recommended:

- creating a new service unit to establish digital capability

- optimising a subset of transactions

- developing capabilities for transaction delivery that can be used across Victorian Government agencies.

Optimising transactions means making them more efficient by making them consistent, reducing unnecessary steps and delivering them digitally.

The Victorian Government allocated $15 million for planning this new service unit—now known as Service Victoria (SV)—in the 2015–16 State Budget and a further $81 million for its development in the 2016–17 State Budget. As at 30 June 2020, SV has cost the Victorian Government $156.9 million.

The implementation of SV was complex. It involved multiple interrelated projects, information and communications technology (ICT) and whole-of-government collaboration.

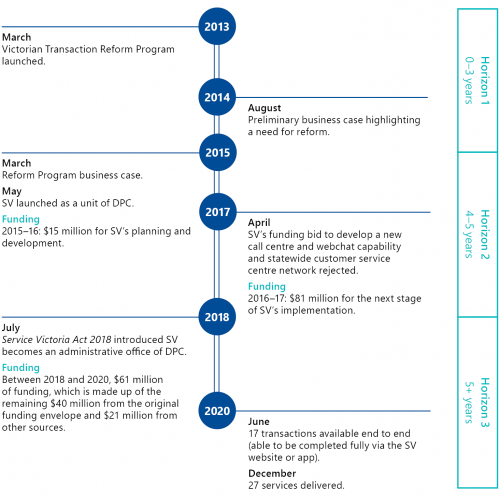

The first three years

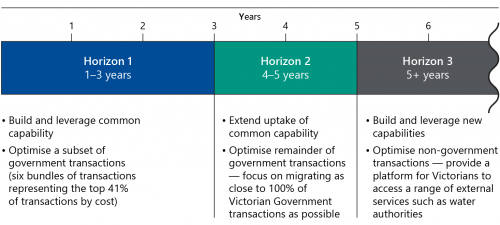

The Reform Program business case sets out three delivery 'horizons'. DPC anticipated that in the first three years, or Horizon 1, SV would deliver the scope shown in Figure A.

Figure A: Delivery of Horizon 1 scope (2015–18)

| Horizon 1 scope | Delivered? | VAGO commentary |

|---|---|---|

|

Establish a digital platform that allows customers to transact or get information via a website or mobile device |

✓ |

SV has achieved this. It has a website and mobile app that allows customers to transact with government using a consistent design. |

|

Build common capabilities (for example, payment gateways or identity verification functions that any department or agency can use) |

✓ |

SV's capability includes:

|

|

Optimise a subset of government transactions |

Partial |

While SV optimised a subset of transactions, these were still in a testing phase at the end of Horizon 1. The Reform Program business case anticipated that by the end of its first three years, SV would be delivering at least 14 different transactional services. SV did not achieve this. At the end of Horizon 1, SV had delivered transactions for six services (all in a testing phase only) and 12 services in its fourth year. It is still delivering a lower-than-expected volume of transactions. |

Source: VAGO.

The Reform Program business case

The primary purpose of a business case is to provide the government with enough information to make an informed investment decision. DPC's Reform Program business case clearly showed a need for change but lacked sufficient detail.

Narrow range of options

DPC's Reform Program business case referenced alternative solutions interstate and overseas, but it did not explore these as project options.

High-value transactions include transactions that involve manual processes, are costly to government, or could deliver significant savings when delivered on a large scale.

DPC explored four project options. All options were similar and included high-value transactions. The options only differed on the number of services that SV would deliver and whether SV would also offer a complaints portal and customer service strategy. DPC limited its cost–benefit analysis to these options.

DPC did not adequately explore alternatives such as outsourcing to the market or delivering lower-risk transactions to first establish SV's capability.

Estimation of benefits

DPC outlined in its Reform Program business case that SV would drive benefits through transaction reform. Its benefits included:

- improving customer satisfaction and reducing the time it takes for customers to transact with government

- saving the Victorian Government $61 million per year from the improved productivity of government departments and agencies

- increasing the effectiveness of government policy and regulations by making it simple and easy for people to transact with government.

However, achieving these benefits relied on SV:

- optimising a set of existing high volume and high cost to government transactions such as VicRoads licensing services, Victoria Police applications, and the then Land Victoria property services

- being able to deliver and measure improvements in compliance, even though this was not well scoped in the Reform Program business case.

For example, DPC predicted that SV would deliver increased revenue because more people would obtain the required licence or pay their bills if simple and fast digital options were available. DPC suggested that the new agency would measure this by the reduction in unpaid fines.

However, at the time DPC developed the Reform Program business case, the government was already considering an alternative fines ICT solution. Now known as Fines Victoria, this began operation in December 2017. SV did not onboard fines transactions, nor did it have a way to measure whether people's use of SV resulted in fewer unpaid fines. As such, this was unlikely to be a real or attainable benefit.

Reliance on assumptions and estimates

There were inherent problems with some assumptions that DPC used to build its business case and estimate the value of SV's benefits to government. DPC's Reform Program business case assumed that:

- the identified stakeholders would onboard with SV without a requirement for them to do so

- SV would be able to achieve the desired shift from in-person, post, and phone transactions to digital interactions.

In addition, because not all departments and agencies had reliable transaction data, DPC relied on estimates of the cost, volume and type of transactions undertaken.

Lack of key details

DPC's Reform Program business case did not contain the full details and documentation recommended by the Department of Treasury and Finance’s (DTF) business case guidelines, such as a detailed project plan, procurement strategy or stakeholder management plan, funding model, governance framework or a detailed risk management strategy.

Further, DPC did not include in its business case a comparative assessment of what it would cost agencies to implement their own digital solutions. Nor did it include several items that it claimed would be explored as the program progressed, such as whether SV would have a physical presence or baselines for customer satisfaction.

The government considered the business case in 2015. While it recognised that the business case lacked key details, it noted that there was policy merit in the initiative and approved SV for inclusion in the 2015–16 State Budget with:

- an initial commitment of $15 million for planning—including the development of a detailed Program Implementation Plan

- further funding (up to $122 million), which the government would hold in contingency, with release subject to DPC meeting project milestones determined in the Program Implementation Plan.

Failure to revise benefits and costs

The HVHR assurance process subjects identified programs to more rigorous scrutiny and approval processes, including staged reviews.

This includes Gateway and Program Assurance Reviews, where an independent external reviewer provides advice about a project’s progress and likelihood of successful delivery.

As a complex ICT project that required the collaboration of many agencies, SV was subject to the high value high risk (HVHR) assurance process. However, despite Gateway reviews recommending that SV update the business case with revised benefits and costs, neither DPC nor SV made these revisions.

When SV developed Program Implementation Plans, these did not detail and quantify the program benefits or address changes to underlying assumptions even after significant changes and government policy decisions had occurred.

This reduced:

- transparency in the program

- the ability for government to track SV's progress against its original vision, which would have assisted government to:

- decide whether SV remained a viable option

- take action to improve project benefits (such as assess whether the program should be mandatory).

SV’s intended transactional benefits

The Reform Program business case predicted that SV would deliver a net financial benefit of $61 million per year. While SV would achieve almost $8 million per year in benefits through savings in payments and streamlining physical service centres, most of SV's financial value was though providing cheaper and more efficient transactions.

In 2019–20, SV reported that it achieved $6 million in transactional benefits. This is a significant shortfall from the Reform Program business case’s annual transaction benefit estimate of $53 million. The shortfall is because SV did not deliver the volumes or types of transactions that DPC outlined in its Reform Program business case.

This transactional benefit also does not reflect the true transactional savings to government. Rather, it reflects the savings to the agency from transferring the transactions to SV. For most transactions, it does not capture the ongoing costs of the transactions such as agency staff time or other indirect costs.

In 2015, DPC did not have formal agreements with any of its key stakeholders to deliver their transactions. While it had engaged with these stakeholders, it had not 'locked in' the transaction delivery via a contract or formal agreement. SV’s success relies on agencies using it. One of DPC's risk mitigation strategies was that it would not implement SV without a mandated vision. This did not occur. The government chose not to mandate the use of SV and it remains optional for agencies to use.

The subsequent failure to onboard two bundles of transactions that the business case had anticipated has significantly impacted SV’s benefits realisation. These are:

- land registration and title services, with $23.4 million in projected benefits per year

- the full scope of VicRoads transactions, with $17.6 million in projected benefits per year.

Land registration and title service transactions

DPC's Reform Program business case included transactions managed by the then Land Victoria. This was a tenuous assumption because at the time of the Reform Program business case, the then Land Victoria had already begun to deliver some digital transactions via a national digital property platform and had recently transferred to a different department.

In May 2017, the Victorian Government announced a scoping study of land titles registry functions. In 2018, it announced that it would commercialise the land titles and registry functions of Land Use Victoria.

Annual financial benefit is the financial value that SV asserts that it has delivered to government from such things as reduced transaction costs, avoiding costs in investing in multiple platforms and other efficiencies.

SV removed this transaction type and related benefits from its annual financial benefit in July 2017.

VicRoads transactions

DPC expected SV to deliver all licence and registration transactions for VicRoads. However:

- SV does not deliver any VicRoads licence transactions

- at December 2020, SV was only delivering 3 per cent of VicRoads’ online 12-month vehicle registration renewals and 53 per cent of registration checks.

Over the last five years, VicRoads has developed its own digital capacity and now delivers several digital transactions, including online registration checks and renewals, licence address changes, appointment bookings, notifications of vehicle transfers and an option to have a central VicRoads account.

Several factors have contributed to VicRoads' decision not to onboard all transactions with SV. Some of these factors included the development of its own transactions and technology, its uncertainty about SV’s ability to deliver at scale, and the future of the VicRoads registration and licensing division.

Duplicated systems

In its Reform Program business case, DPC highlighted that SV would drive reform, consistency, and the delivery of common capabilities across government, including payments and identity management systems.

DPC advised that over the medium to longer term, the government could decommission high-cost legacy systems and save money. However, agencies such as VicRoads, Ambulance Victoria and Working with Children Check Victoria still run their own digital transactions. This has meant that the Victorian Government has missed the opportunity to realise benefits from one centralised platform. Until departments and agencies decommission legacy systems, the government will continue to pay for multiple, fragmented IT systems and their associated costs.

Overall transaction volume

SV is only delivering a small fraction of its intended transaction volume. DPC estimated that by the end of Horizon 1 (June 2018), SV would be delivering approximately 11 million transactions per year. During the 2019–20 financial year (the end of Horizon 2), SV delivered 814 282 transactions. While this is an increase on previous years, it is a significant shortfall from the business case estimates and makes up only 1.3 per cent of all Victorian Government transactions.

These low transaction numbers are due to:

- the types of transactions that SV has onboarded

- the low percentage of digital transactions that agencies have directed to SV for some transactions.

COVID-19 related transactions

A QR code is a type of barcode that can be scanned by mobile phone cameras. The QR poster is the printout of that barcode that businesses can use.

Between July to December 2020, SV introduced five transactions related to COVID-19, including border permits and exemptions, QR check-ins and poster generations, and regional travel vouchers.

SV's ability to quickly stand up these transactions demonstrates the ability of SV to build and utilise its technology. For example, SV set up online applications for regional travel vouchers in 2.5 days.

The introduction of the COVID-19 transactions has increased SV’s transaction volume to 2.57 million transactions in six months. However:

- QR scans are largely automated and are low value on a cost-per-transaction basis

- SV counts each individual QR poster generation, which may not be a true indication of the use and value of the service

- these transactions are likely temporary.

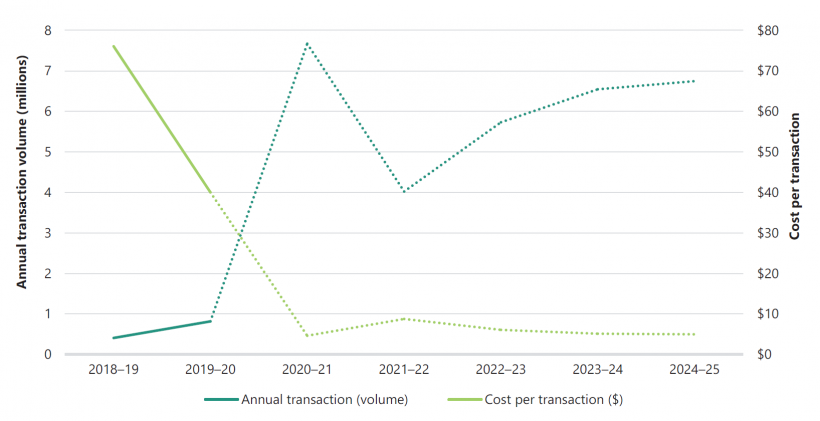

SV’s predicted volume

SV states that it is on track to deliver 6.7 million transactions (worth $20 million per year) by the end of its first 10 years, in 2025. It has not included COVID-19 transactions as a long-term benefit.

SV’s predicted volume is still lower than Horizon 1's initial scope of 11 million transactions by 2018 (worth $53 million). SV’s ability to deliver its projected volume is dependent on it onboarding new services and delivering an increased proportion of the transaction volume for the services it currently delivers. SV has a pipeline of transactions that it is developing, but it is too early to tell whether it will deliver the scale of transactions anticipated.

Stakeholder engagement

As it is not mandatory for agencies to use SV, it is essential to SV's success that it can engage and earn the trust of government agencies. This includes understanding agencies' needs and retaining their commitment.

Barriers to onboarding agencies

During the development of the Reform Program business case, various stakeholders supported the proposed SV. However, by the end of its first three years of operation, SV had still not onboarded many of the forecast transactions. Factors leading to this include:

|

SV-related factors such as … |

External factors such as … |

|

lack of clarity on its scope and when it would be ready to onboard transactions |

agencies' reluctance to onboard new services without first testing SV |

|

technical solutions not being ready when agencies wanted, which meant that agencies continued with their own digital projects |

uncertainty about SV's ongoing funding, which affected stakeholders’ trust in its longevity |

|

failure to secure agreements with stakeholders to lock them in at an early stage, despite early recommendations in Gateway and Program Assurance reviews |

government policy decisions for key transactions such as land titles and registration |

DPC outlined in its Reform Program business case that SV would benefit from being close to central government. As such, SV was established within DPC, which was ultimately responsible for implementing SV and ensuring its success. However, we saw limited evidence of DPC encouraging agencies to use SV prior to 2020, when it advocated for SV to have a role in the reform of the fines system.

Stakeholder feedback

Almost all of the agencies that use SV stated that SV's capabilities have grown. However, SV does not have a mechanism to collect formal feedback from agencies, such as an annual survey. Rather, it meets with agencies during, prior to and after it has onboarded transactions. This is a missed opportunity for SV to identify issues from a stakeholder’s perspective and track its stakeholder engagement performance over time.

Recommendations about stakeholder engagement

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Premier and Cabinet | 1. develops and implements a government agency stakeholder engagement strategy with the aim of increasing agency participation and uptake of Service Victoria's services and reusing existing technology (see Section 3.5). | Accepted |

| Service Victoria | 2. introduces an annual survey for agencies that use Service Victoria to track its performance over time and address any areas for improvement (see Section 3.5). | Accepted |

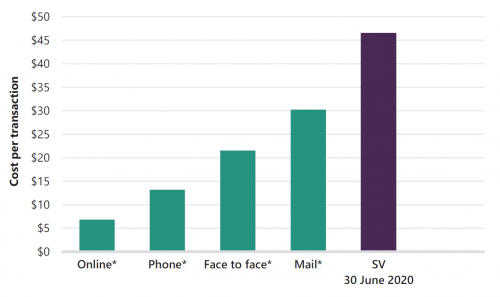

SV’s cost per transaction

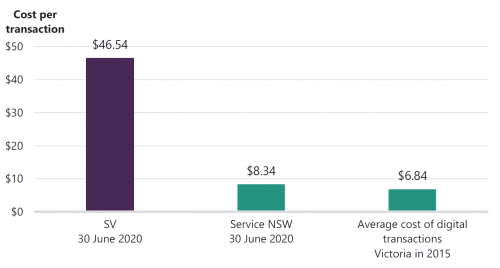

Due to its low transaction volume, SV is costly on a per-transaction basis. In 2019–20, it cost SV $46.54 to deliver each digital transaction. As shown in Figure B, this was more expensive than face-to-face transactions.

Figure B: SV’s cost per transaction (2019–20) compared to other channels

Note: * DPC outlined these estimates in the Reform Program business case following an assessment of the cost of Victorian Government transactions. We have adjusted these for inflation. SV currently only delivers a digital option.

Source: VAGO, from SV data and the Reform Program business case.

The Victorian Government's annual state budget spend is documented in an annual Appropriation Bill. This grants the government permission to spend public money on the items in the budget.

Direct costs are expenses that directly go into producing the good or service (such as such as technology and licensing fees) whereas indirect costs apply to more than one business activity (such as rent and general staffing costs

SV's cost per transaction is based on SV’s budget appropriation for 2019–20 divided by the number of transactions it delivered that year. As SV delivers more transactions, this cost will decrease as shown in Figure C. However, there are limitations to this calculation. It does not reveal SV's direct or indirect costs, nor does it reflect the complexity of the transaction. Further, if SV delivers one high volume, low complexity transaction (such as QR scans), this will skew the transaction cost despite the transaction requiring limited customer interaction.

Figure C: Impact of COVID-19 transactions on SV's cost per transaction

| Between 1 July 2020 and 31 December 2020 SV delivered … | Inclusion of these transactions using SV's method results in a cost per transaction of … |

|---|---|

| 0.60 million transactions from its existing services | $34.62 |

| Plus 0.53 million new COVID-19 related transactions (excluding QR scans and posters) | $18.39 |

| Plus a further 1.44 million QR scan and poster generation transactions | $8.09 |

Source: VAGO from SV data.

SV's annual financial benefit

In 2015, DPC estimated that SV would deliver an annual financial benefit to the Victorian Government of $61 million per year. In January 2018, SV revised its benefit realisation framework and calculation of its annual financial benefit. It:

- revised down its target to $30 million per year to reflect the removal of Land Victoria transactions

- added several benefits not explored in the Reform Program business case such as avoided costs, re-use benefits, intellectual property, payment savings and time returned to customer.

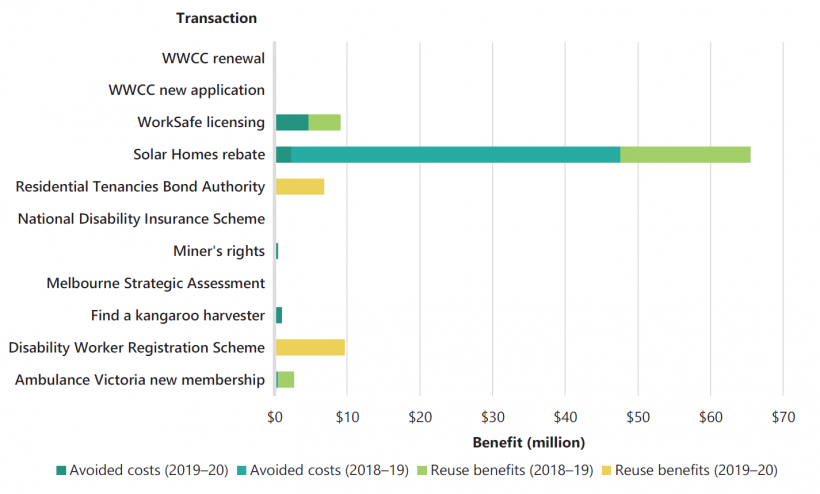

SV reported that it achieved this annual benefit for both 2018–19 ($75 million) and 2019–20 ($45 million). However, SV's actual benefit to government is likely to be less than SV reported. Across the two years, SV has claimed:

- $50 million in benefits from reusing its technology to deliver transactions

- $52 million in avoiding costs to agencies through avoiding a more expensive market solution and procurement costs. Most of this benefit was from Solar Homes transactions (SV claimed $48 million for these transactions).

As Figure D shows, there are limitations with these benefits.

Figure D: Added SV benefits and their limitations

| Benefit | Basis for benefit calculation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

|

Avoided costs |

The amount that government agencies save by using SV. These savings may occur because SV:

|

This is a valid benefit to government. However, the quantum that SV has claimed to date is based on several questionable assumptions and estimates. SV estimates the value of this benefit by using assumptions and available data. It is difficult to determine the accuracy of this estimate as in most cases, the agency does not need to get market quotes. In some instances, these costs are theoretical because:

|

|

Re-use benefits |

The value provided by SV’s reusable capabilities, such as cloud-based infrastructure, common capabilities (for example, digital licences), centralised payment gateways and digital support, which make the costs of onboarding additional transactions low. The reason that SV can deliver a cheaper alternative and avoid agency costs is because it can re-use its capability. |

Including this benefit is double counting. For example, SV has claimed the avoided cost of building digital capability for the Solar Homes transactions as well as the savings from reusing its technology and processes to provide a solution. SV was set up to build common capabilities and its ability to deliver more services at less cost is reflected in the overall cost of transaction. The benefit is achieved when the capability is actually re-used. |

|

Time returned to customer |

The time customers save by transacting faster. |

While this is a valid benefit to customers and is in line with the objectives of the Reform Program business case, it is not a clear and direct financial benefit to government and should be counted separately to SV's annual benefit. Further, this benefit is driven by an efficient, digitised process. It does not need to be SV that delivers it. As such, there is potential that this benefit could be achieved by other new digital systems that are factored into avoided costs. |

|

Payments |

Savings from the introduction of PayPal. |

The ability to realise significant benefits from PayPal has a high degree of uncertainty as it depends on agencies offering and customers using PayPal. It may also be limited in its life span due to changing payment technologies. |

|

Intellectual property |

Reusing intellectual property across government, such as SV templates and research. |

The calculation is based on assumptions about the value of the intellectual property and is not supported by clear evidence or a consistent underlying methodology. |

Source: VAGO.

Recommendation about SV's annual financial benefit

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Service Victoria | 3. revises its annual benefit measure to ensure that it accurately reflects direct savings for government and does not include double counting of benefits, particularly re-use benefits or benefits to stakeholders other than government (see Section 3.3). | Accepted |

Reporting and oversight

DPC is the lead agency for the Victorian Government's Information Technology Strategy 2016–2020. A key priority of this strategy is ensuring that Victorians can interact digitally with government services in a way that is useful, easy, and always available.

Key to this strategy was the need for DPC to drive increased digital uptake by Victorian departments and agencies. DPC's Reform Program business case outlined that SV would define the strategy, standards and policies that must be adhered to by departments and agencies in the delivery of transactional services.

This model has changed over time. SV sets customer service standards and identity verification standards, but only for the services that it delivers. It does not define whole-of-government transactional strategy or provide a consultancy service for agencies.

DPC has published a series of best-practice guides that aim to make digitisation easier for agencies to understand and implement. It also suggests that agencies assess how they are performing by measuring:

- user (customer) satisfaction

- time to completion

- transaction completion rate

- cost per transaction

- digital take-up, which refers to how many customers are using the service digitally compared to in-person, via phone or mail.

DPC does not know how many transactions exist across government, what they cost and whether they are digital as agencies do not report to DPC or publicly on these measures. While DPC commissioned work to estimate this in 2015, neither SV nor DPC has updated this data. This reduces the ability of government departments and agencies to:

- make data-driven decisions about how to improve their services

- compare data across multiple government services

- be open and transparent to the public about the performance of their services.

While SV reports on these measurements internally, it does not publicly report on its cost to deliver transactions or volume of services. SV's only public performance measure is customer satisfaction, which DPC includes in its annual report and the Victorian Government Budget Paper No. 3 (BP3) reporting. While customer satisfaction is an important aspect of SV's service delivery, it is also important whether Victorians use SV and whether SV is reducing the costs to government to process transactions.

Recommendations about reporting and oversight

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Premier and Cabinet | 4. introduces a Victorian Government Budget Paper No. 3 measure and target for Service Victoria's cost of transactions, volume of transactions and the number of services Service Victoria delivers (see Section 3.4) | Accepted |

5. establishes a requirement for departments and agencies delivering digital services to report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet on the key performance indicators outlined in its Measure how content performs—digital guide including:

|

Accepted | |

| 6. develops a dashboard to report publicly on the performance of agencies delivering digital services against the key performance indicators outlined in its Measure how content performs—digital guide (see Section 2.5). | Accepted |

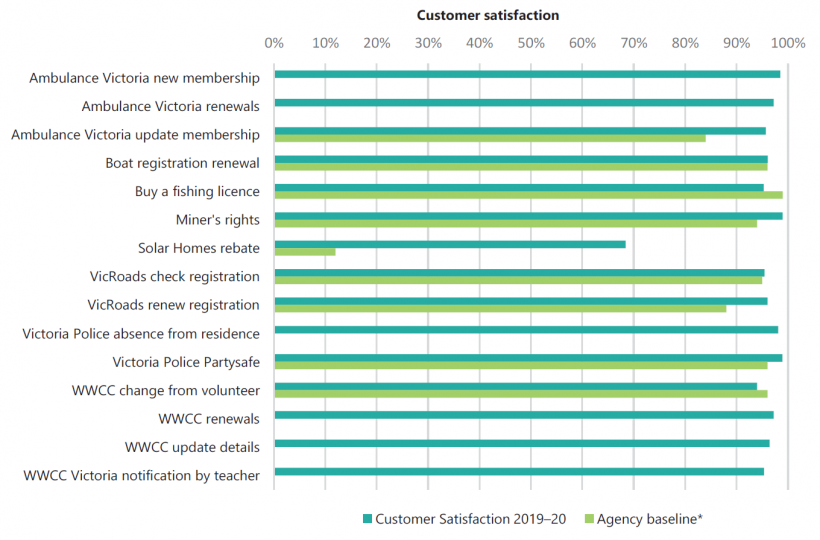

SV's customer satisfaction results

SV achieved its customer satisfaction target of 95 per cent in 2018–19 and 2019–20.

Customer Satisfaction (CSAT) is a metric that measures how satisfied a customer is based on a specific scale and formula. It is separate from the term 'customer satisfaction', which can be used in its common form to mean how satisfied customers are with a service.

Net Promotor Score measures how likely a customer would recommend a service and Customer Effort Score measures how easy it is to use the service.

However, it is difficult to compare SV across like services as there is no standard customer satisfaction measure used for public sector agencies in Victoria and other states. Each department or agency chooses its own metric. This can vary from CSAT (a customer satisfaction methodology) to Net Promoter Score, Customer Effort Score, or their own customer satisfaction metric.

SV has used its own approach to measure customer satisfaction. This approach has been consistent and relies on statistically reliable data. However, it only captures feedback from customers who have finalised their transaction with SV. This means it potentially excludes customers who did not complete their transaction due to dissatisfaction with the service.

|

SV’s customer satisfaction approach … |

The commonly used CSAT metric … |

|

Uses a five-point scale for customer feedback as follows:

|

Uses a five-point scale similar to SV |

|

Uses a mix of neutral and positive scores (3s, 4s and 5s) to calculate its result |

Uses an average of only positive scores (4s and 5s) to calculate its result |

|

Has a high target (95 per cent) |

Is usually a lower target (75–80 per cent) |

|

Resulted in 96 per cent customer satisfaction for 2019–20 |

If used by SV, would result in 82 per cent customer satisfaction for 2019–20 |

Recommendation about customer satisfaction

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Premier and Cabinet | 7. reviews its current digital standards to include a clear key performance indicator for customer satisfaction together with the preferred customer satisfaction measurement approach agencies should use (see Section 2.5). | Accepted |

Compliance with government regulations and policies

The Reform Program business case highlighted that the transaction reform would increase peoples' compliance with Victorian Government regulations and policies due to more consistent, accessible, and simplified processes.

SV cannot show that it has achieved this benefit. SV's measures do not directly relate to SV's actions or specific policies and regulations, as shown in Figure E.

Figure E: Performance measurement and tracking

| Reform Program business case measures used to assess achievement of this benefit | Commentary |

|---|---|

|

The transaction completion rate (the percentage of people who complete a transaction with SV) |

There is no measurement of the number of digital transactions across the Victorian Government. We estimate current transaction numbers based on 2015 data. SV is not the sole provider of all services and the measure does not reflect increased digital compliance or indeed more people completing core compliance transactions, such as licences. |

|

Increased use of government services in the longer term |

SV has a target of 2 per cent increase on its services every year. This does not consider the growth rate of all government transactions or the growth in Victoria’s population. |

|

Increased revenue from greater compliance due to a reduction in unpaid fines |

SV does not deliver many transactions that are subject to regulation and fines. Out of 17 end-to-end transactions SV delivered by 30 June 2020, it had five transactions where a customer may be fined for non compliance (such as a failure to hold a fishing licence or drive with a valid car registration). SV also does not deliver fines transactions and has no way of tracking revenue or a reduction in unpaid fines. SV revised its measures in 2018 and no longer tracks or reports on this measure. |

Source: VAGO.

Recommendation about government regulations and policies

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Service Victoria | 8. reviews its benefits reporting and the inclusion of the compliance with government policy and regulations benefit given the challenges in the attribution and measurement of this (see Section 3.3). | Accepted |

Baselines used by SV

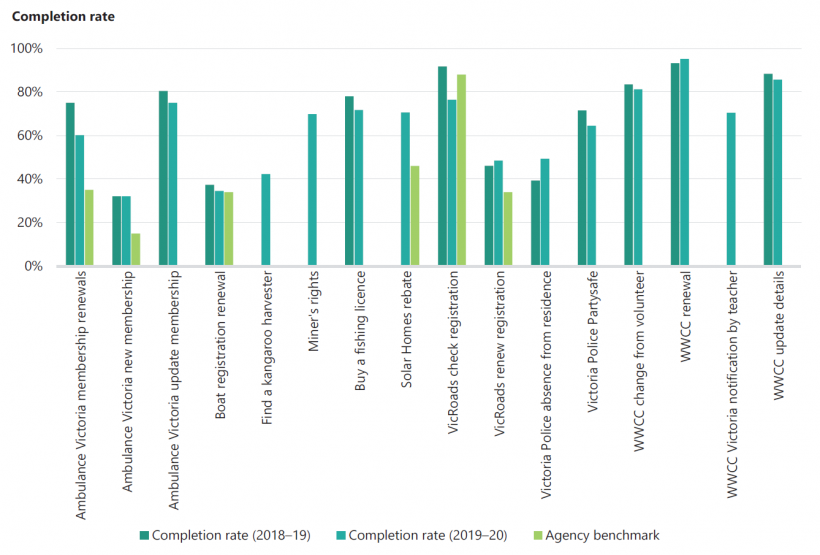

Most transactions are not new to agencies. Agencies should have data on how much a transaction costs to deliver together with other key metrics such as completion rate, customer satisfaction and length of transaction. These are referred to as transaction baselines.

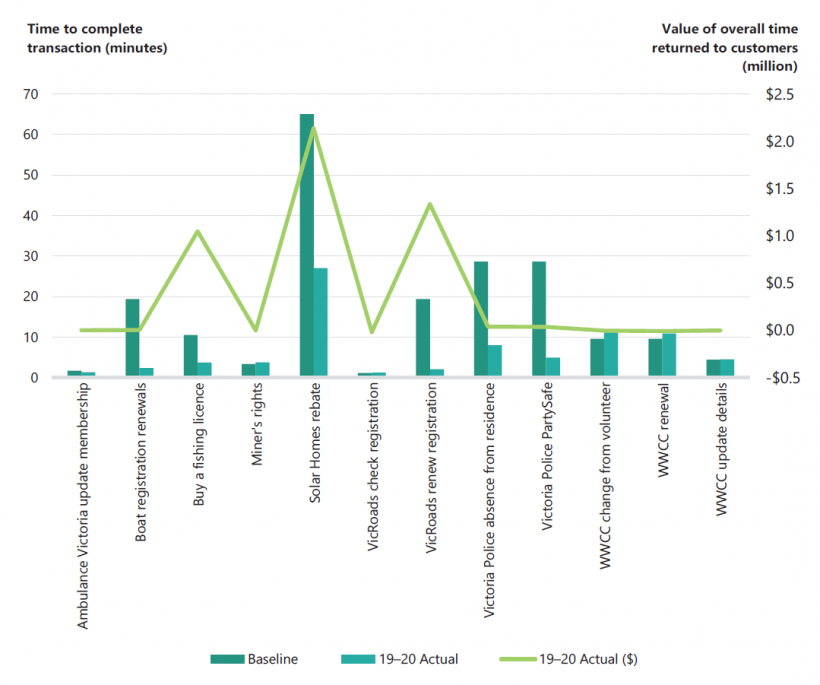

SV measures several key performance indicators (KPI) relative to the transaction baseline of the agency that uses SV. These measures include:

- reduced cost of transactions

- completion rate

- improvement in customer satisfaction

- reduced effort to undertake a transaction.

Agencies do not always have reliable data on their transactions. To address this, SV undertook its own research and used this to set baselines for measuring its performance against customer satisfaction, transaction cost, time to completion and completion rate. However, SV did not do this for all transactions. For the transactions that it did obtain baselines for, SV's approach to establish these baselines was unreliable due to low sample sizes.

Recommendations about baselines

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Service Victoria | 9. reviews its current baselines for customer satisfaction, time returned to customer, completion rate and transaction cost to ensure that they are statistically reliable and relate to the benefits they measure (see Section 2.5) | Accepted |

10. develops processes to ensure that future transactions have reliable baselines (see Section 2.5), including:

|

Accepted |

1. Audit context

Population growth and changing consumer expectations are placing increasing pressure on the cost, timeliness and quality of government services. Digitising transactions can help to address this.

The Victorian Government launched SV in 2015 to transform the way that government agencies deliver transactions to citizens, improve customer satisfaction, and reduce costs.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Victoria’s need for digital services

The demand to access services online is growing rapidly, as is people’s expectations of the range of services they should be able to access anytime and anywhere.

In 2015, Victorians completed around 55 million state government transactions by mail, phone, online or face-to-face. Considering the state’s population growth since, and assuming government transactions have grown in proportion, we estimate that Victorians completed over 62 million transactions in 2020. Transactions include:

- making a payment, such as vehicle registration or topping up a myki (public transport) card

- applying for a document, licence, or government program, such as a fishing licence, birth certificate, or the Solar Homes rebate

- renewing or changing personal information, such as updating personal details for a driver’s licence or a Working with Children Check (WWCC).

While some Victorian Government transactions are fully available online, others require customers to fill in paper applications or visit an office. It can also be difficult for customers to find information about services because the Victorian Government has hundreds of phone hotlines and websites. This is inefficient and costly to both consumers and the government.

The 2014 Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of Victorian Government transactional services Preliminary business case (the Preliminary business case) and the Reform Program business case, which were commissioned by DPC and the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation, highlighted the need for the Victorian Government to reform the way it delivers transactions.

These business cases found that the government had not embraced modern technology and was lagging behind other jurisdictions. Figure 1A illustrates the state of digital service delivery in Victoria in 2015.

FIGURE 1A: The state of Victorian Government digital service delivery in 2015

Source: VAGO, from the Preliminary business case and the Reform Program business case.

The Reform Program business case also highlighted that, in 2013, Victoria’s customer satisfaction and ease of completing transaction rates were low compared to other jurisdictions.

1.2 The Victorian Transactions Reform Program

In 2015, DPC recommended that the government establish a new service unit, which is now known as SV. This aimed to address three primary transaction delivery challenges, as Figure 1B shows.

FIGURE 1B: The Victorian Government’s three primary transaction delivery challenges

| Challenge | Impact |

|---|---|

| Ease and speed of transactions | Not meeting the public’s expectations, which causes increased red-tape costs, reduced productivity and reduced public satisfaction (including non compliance) |

| Complex, duplicated and fragmented transactions | Low digital uptake, which results in increased costs to the government |

| Increasing demand | Delivery models will not meet growth in transaction volumes, which could result in service failure and non compliance by the public |

Source: VAGO, from the Preliminary business case and the Reform Program business case.

Establishing SV

The vision DPC expressed in its Reform Program business case—to establish digital transactions across Victorian Government agencies—was consistent with the Victorian Government ICT Strategy 2014–15. This strategy had objectives to implement new digital and mobile channels for Victorians, standardise systems, improve productivity and increase the government’s capability to innovate.

In its Reform Program business case, DPC predicted that SV would deliver three key benefits:

- improved customer satisfaction and productivity (reducing the amount of time it takes for customers to transact with the government)

- increased compliance with regulation (increased effectiveness of government policy and regulation)

- increased government productivity (cost savings).

DPC highlighted in its Reform Program business case that to achieve these benefits, the government must:

- transform its approach to transactional service delivery

- make it simpler, faster, and more convenient for people to access government services.

As Figure 1C shows, the Reform Program business case outlined that SV would be delivered in three key stages, or ‛horizons’.

Common capability refers to projects such as proof of identity, customer record keeping and other core capabilities that can be used for all transactions.

Optimising transactions means making them more efficient by improving consistency, reducing unnecessary steps and delivering the transaction digitally.

FIGURE 1C: The three horizons

1.3 Timeline

1.4 Service Victoria

SV's project management approach

The Victorian Transactions Reform Program (Reform Program) was complex. It involved establishing a new unit that would provide a whole-of-government approach to transactional service delivery, including the development and implementation of a technology solution.

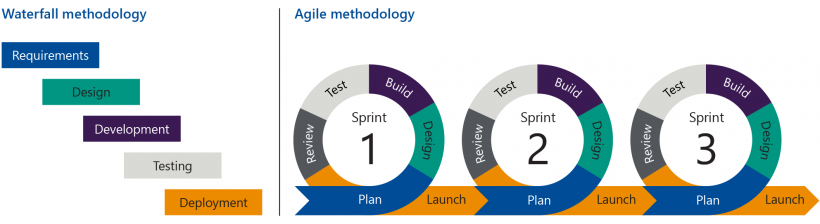

Agile project management is an iterative approach to delivering a project throughout its lifecycle. It uses feedback loops to continually review and improve its product.

SV aimed to address past failures with government ICT projects, such as delays and budget blowouts, by blending an Agile and waterfall project management approach.

The waterfall method is a more traditional project management method. Projects that follow this approach outline their specifications before they start and deliver them at predetermined stages. This approach often does not involve the end user until late in the project. Changing requirements at that late stage can be expensive and time consuming. This can contribute to projects not being delivered on time, within budget or at all.

SV therefore took an Agile and iterative approach to progressively define its program and technology requirements and build capability. It then used a waterfall model of defined program phases designed to provide checkpoints and governance at key stages. Figure 1E shows the components of these methodologies.

FIGURE 1E: Waterfall and Agile project management methodologies

Source: VAGO, from publicly available information.

In addition to these methodologies, SV also used the lean start-up methodology in developing its product, with the core intent of maximising customer value while minimising costs. It involves challenging processes and the underlying thinking to determine whether it can be more efficient.

The government may establish an administrative office that is linked to a department.

The relevant department is responsible for the general conduct and effective, efficient and economical management of the administrative office's functions.

In some cases (such as with SV) legislation gives specific powers and responsibilities to the administrative office.

SV today

On 1 July 2018, SV became an administrative office of DPC. The Service Victoria Act 2018 outlines SV’s functions. This Act:

- enables SV to deliver government services

- provides a regulatory framework for SV to provide identity verification functions

- allows agencies to transfer their functions to SV.

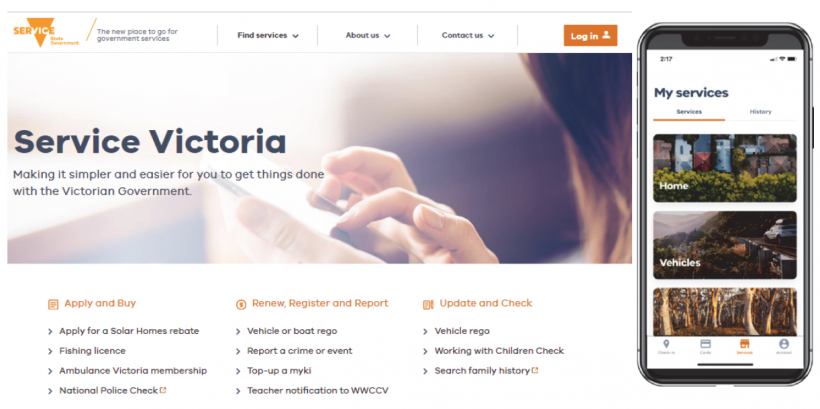

Customers can transact with SV via its website or a mobile app. Figure 1F shows what SV’s website and app look like.

FIGURE 1F: SV’s platforms

Source: SV.

Customers have the choice to transact as a guest or create an account if they want SV to store their information for future use. The SV app also allows customers to store digital licences. For now, SV has only released digital fishing licences.

SV provides three types of services:

- end-to-end transactions, where a customer can complete the entire transaction via the SV website or app

- links to other services, where a customer clicks a link on SV’s website and is redirected to the relevant agency’s website

- white-label transactions—these are capabilities that SV has built for an agency but does not host on its website. For example, the identity verification component of a WorkSafe Victoria licence.

We discuss the transactions that SV offers in Chapter 2.

1.5 DPC’s role and responsibilities

DPC is responsible for developing and leading whole-of-Victorian-Government policies, including the Information Technology Strategy 2016–2020. This strategy’s key deliverables include providing better digital transactions and implementing SV.

SV was initially approved as a project within DPC so it could be established quickly, rely on existing supporting policies and systems and be close to the centre of government and decision-making. DPC was responsible for the successful delivery of SV.

Program and project governance

The Senior Responsible Officer led SV's operation, management, and implementation. They were responsible for recommending program level changes or changes that represent a material departure from the business case to DPC's Secretary and the then Special Minister of State.

SV had over 220 deliverables for the program. Many of these were interrelated. Rather than having individual project boards to oversee each key project, SV used an Agile approach to delivery and conducted frequent cycles of build–test–learn phases. It then used one project control board to oversee the delivery of the outcomes.

Audit and Risk Management Committees

DPC's Audit and Risk Management Committee's (ARMC) purpose is to provide independent assurance and advice to DPC's Secretary on the effectiveness of the department's finance management, performance, compliance and risk management functions.

In 2015, the DPC ARMC formed the SV subcommittee to assess and make recommendations on SV's governance and monitor risk. This subcommittee was disbanded in 2016 and replaced by a Program Control Board (PCB). Appendix I outlines the role of these committees and period of time they were operational.

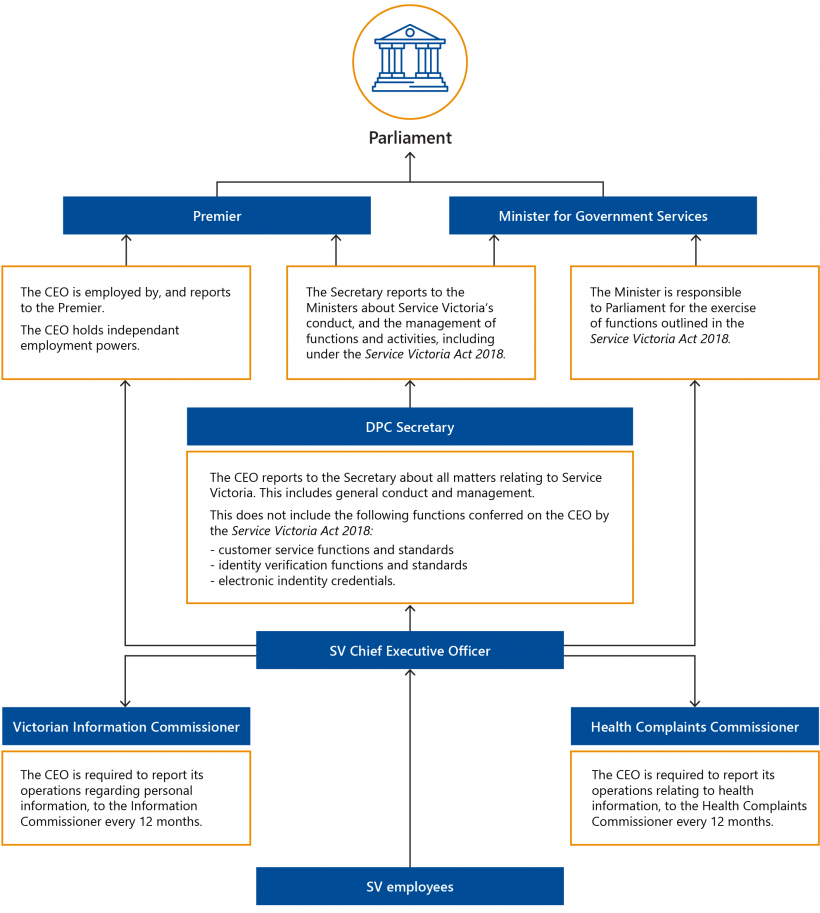

Current governance arrangements

In 2018, SV became an administrative office of DPC and gained powers and responsibilities under the Service Victoria Act 2018. SV's Chief Executive Officer reports directly to the Minister for Government Services for functions exercised under the Service Victoria Act 2018 and reports to DPC's Secretary on the general conduct of SV. This included the establishment of an internal audit function to provide assurance to SV, the DPC Secretary and the ARMC about SV’s operations. SV must follow DPC’s standards, policies, and governance frameworks.

SV's Board of Management (BoM) is responsible for overseeing SV’s operations and functions. It establishes SV’s strategic direction and provides assurance over SV's benefits realisation. The BoM is made up of SV’s Chief Executive Officer, Chief Information Officer, three executive directors and two directors.

Figure 1G outlines SV’s governance arrangements.

FIGURE 1G: Governance arrangements

Note: SV was accountable to the former Special Minister of State between May 2015 and March 2020, after which time the Minister for Government Services replaced the former Special Minister of State.

Source: VAGO, based on legislation and SV’s governance policy.

2. Benefits of SV

Conclusion

SV has delivered good customer satisfaction results for the limited services it offers. However, it has realised only a small proportion of the benefits expected in the Reform Program business case.

In 2019–20, SV achieved transactional benefits of $6 million—well below the $53 million per year that the Reform Program business case predicted. It has also not achieved measurable improvement of people following government regulations and policy, as SV is only conducting about 1 per cent of government transactions.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Realisation of the Reform Program’s expected outcomes

Now in its fifth year of operations (or Horizon 3 of the program), SV has delivered key components of the Horizon 1 scope. However, because of the limited range and type of transactions moved onto its online platform, SV has not achieved many of the expected outcomes.

Program scope and five-year vision

In its Reform Program business case, DPC established the scope for SV’s first three years (or Horizon 1) of transaction reform and set its longer-term vision as shown in Figure 2A.

FIGURE 2A: Program scope and SV's progress

| Timeframe | DPC's expectations of SV | Achieved? | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Horizon 1 |

Establish a digital platform |

✓ |

SV has a website and mobile app with consistent design elements, allowing customers to transact with government using either platform. |

|

Build common capabilities that any department or agency can use |

✓ |

SV's capability includes:

|

|

| Optimise a subset of government transactions |

Partially, but not those originally intended |

While SV has optimised a subset of government transactions, it has delivered a different mix of services than outlined in the Reform Program business case, many of which are lower in volume and complexity. |

|

|

Horizon 2 |

Extend its capability to the remaining Victorian Government transactions resulting in a potential annual benefit of $120 to $150 million a year |

✕ |

SV is not yet delivering this scale of transactions. SV is delivering a similar number of transactions to that anticipated in Horizon 1. While SV delivers transactions across different departments and agencies, it does not deliver transactions for all departments or any transactions from local councils or water authorities. |

|

Horizon 3 |

Provide a platform for Victorians to access a range of services including transactions from local councils and water authorities |

In progress |

Note: SV was allocated three years of funding in the 2020–21 State Budget to continue its operations and partner with local governments to assist with streamlining business licence processing.

Source: VAGO.

SV has also only fully achieved two out of 10 specific outcomes outlined in the Reform Program business case and expected to be delivered in the first three years.

SV's ability to achieve these outcomes was impeded by:

- changes in the program scope such as changed transaction mix and the decision not to proceed with a whole-of-government complaints system

- government decisions, such as not to proceed with a storefront or physical presence

- poor stakeholder engagement and agency decisions not to use SV resulting in fewer transactions onboarded than expected.

Figure 2B summarises the status of these outcomes.

FIGURE 2B: Horizon 1 Reform Program outcomes and status

| Expected outcome | Achieved? |

|---|---|

| A consistent digital experience for the customer regardless of the transaction type and department. Government leveraging cloud and mobile technologies to improve customers’ experience, access and cost | ✓ |

| Multipurpose ‛tokens’ (evidence of the transaction undertaken that can be used by multiple departments and agencies and can be stored digitally on phones and the web) | ✓ |

| A new government unit that facilitates service delivery and sets standards with senior sponsorship and metrics fostering good service, reduced costs and increased pace and agility | Partially |

| Standardised data verification and customer record sharing, leading to reduced form filling and fewer face to face interactions required to prove identity and apply for services | Partially |

| Efficient and effective development and maintenance of legislation and policy impacting transactions | Partially |

| Consistent use of low-cost, highly reliable payment methods across all Victorian Government | Partially |

| A significant increase in the number of transactions completed with little or no human interaction | ✕ |

| Foundations laid for an optimised physical footprint (for example, retail outlets and contact centres) enabled by a greater digital uptake | ✕ |

| Reduced complaints, which are captured and analysed from a whole-of-government perspective | ✕ |

| Lower operating expenditure and total costs of ownership, primarily through migration of transactions to lower cost channels | ✕ |

Note: Appendix D outlines SV’s achievement of Horizon 1 outcomes in further detail.

Source: VAGO analysis of the Reform Program business case and SV data.

2.2 Delivering the intended transaction volume and mix

NPV is the value of future cashflows over the life of an investment. It takes into account all revenue and expenses together with the timing of each.

A positive NPV results in profit, while a negative NPV results in a loss.

In its Reform Program business case, DPC anticipated SV would deliver a net present value (NPV) of $97 million over 10 years and that in Horizon 1, SV would:

- establish both an online and physical (storefront) presence

- deliver the top 41 per cent of all government transactions by cost—approximately 11 million transactions each year.

SV did not achieve this transaction target, and so is not on track to deliver the anticipated NPV.

Customer accessibility: online versus storefront

DPC’s Reform Program business case outlined that SV would to be accessible both online and via storefront locations. DPC flagged that establishing an in-person presence would require further exploration and development of a separate business case. The government did not approve this later business case. As a result, SV adjusted its focus to digital-only transactions and has not achieved the added benefits that a physical presence would bring.

Transaction scope and mix

By the end of Horizon 1, SV had delivered only one of the 14 transactions originally within scope of the Reform Program business case—VicRoads end-to-end registration renewals, although this was not exclusive. By 2019–20 it had added WWCC transactions.

DPC's estimates of SV benefits relied on SV onboarding particular transaction bundles, many of which were high volume and costly for the government to deliver via existing channels. Two of the most important bundles were for Land Victoria and VicRoads. However, SV was not able to fully onboard either of these:

|

SV was not able to onboard … |

Because … |

Impacting SV's delivery of financial benefits, as … |

|

Land Victoria’s property registration transactions, which was estimated to save $23.4 million per year. |

|

The 2018 Program Assurance Review (Gate 5 equivalent review) estimated that removing land registry and titles transactions would result in a negative NPV of $44.2 million over 10 years. On this basis, establishing SV would not have been financially viable. |

|

Most of VicRoads’ registration and licensing transactions, which was estimated to save $17.6 million per year. |

SV was not ready to release its beta version (a version of the technology which is still undergoing testing) until October 2017. As such, VicRoads continued developing its own digital capabilities including the establishment of a myVicRoads portal. It has released several digital transactions including online registration checks and renewals, licence address changes, appointment bookings, notifications of vehicle transfers and an option to have a central VicRoads account. The timing of VicRoads' decisions about its own registration and licensing functions, along with SV's technical capabilities at the outset impacted what SV could deliver. The Victorian Government is conducting a scoping study into reform options for VicRoads registration and licensing. These decisions may further impact the use of SV. |

DPC's Reform Program business case estimated that delivering 80 per cent of registration transactions and 60 to 70 per cent of licensing transactions digitally would deliver annual benefits of $6.1 million and $8.4 million respectively. As at December 2020, SV was not processing any VicRoads licence transactions. It delivered 3 per cent of VicRoads’ registration renewals and 53 per cent of registration checks. |

There are several reasons why SV did not deliver the original transaction mix, including that it was not mandatory for agencies to use SV and many decided to delay, defer or not onboard at all with SV. We discuss this further in Chapter 3. A detailed examination of transaction delivery is also shown in Appendix E.

Revising the transaction mix

SV is now aiming to deliver a positive NPV of $25.17 million over 10 years. This relies on it adapting the transaction mix and delivering additional benefits not listed in the original Reform Program business case. We discuss these new benefits further in Section 3.3.

To prove its capability, SV revised the transactions that it would onboard in 2018. These changes were listed in its Program Implementation Plans.

The types of transactions SV onboards influence the ultimate volume that it can deliver. For example, fewer people will register an 'absence from residence' with Victoria Police than would apply for a criminal history check.

Figure 2C shows the number of services that SV has delivered over time and how this compares to estimates in the Reform Program business case.

FIGURE 2C: SV's transaction volume (business case estimates and after changes to the transaction mix)

| Reform Program business case estimate(a) | 2017–18 actual(b) | 2018–19 actual | 2019–20 actual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of separate end to end services available via the Service Victoria website (such as fishing licences, registration renewals) | 14 | 6 | 12 | 17 |

| Number of digital transactions processed by SV | 11 million | 53 311 | 406 595 | 814 282 |

| Number of Victorian Government transactions processed via all channels(c) | 55 million (SV would deliver 21%) |

60.3 million (SV delivered 0.09%) |

61.5 million (SV delivered 0.7%) |

62.5 million (SV delivered 1.3%) |

Note: (a) The figures are based on Reform Program business case estimates prepared in 2015 with the transactions to be delivered at the end of Horizon 1 (i.e. by mid-2018).

(b) 2017–18 was SV's beta (testing) phase.

(c) DPC conducted an exercise to estimate transaction volume in 2015. The figures between 2017 and 2020 are VAGO estimates based on the impact of population growth.

Source: VAGO analysis of SV data.

Other impacts on SV's transaction capacity and timing

SV's governing legislation, the Service Victoria Act 2018, did not come into force until 1 July 2018, almost two years after Cabinet gave in principle approval for the legislative model to transfer customer service functions to SV. The delay in passing this legislation contributed to delays in SV delivering transactions.

Delivered SV transactions

SV offers a range of end-to-end transactions and links on its website to other external services. As Figure 2D shows, as at June 2020, SV had 17 end-to-end transactions available on its website and was the primary provider of seven of these.

FIGURE 2D: Transactions offered by SV 2019–20

| Category | End-to-end transaction | Transactions delivered in 2019–20 | Other options for completing the transaction | |

| Total delivered by SV | Proportion of all transactions (%) | |||

| Crime and the law | Victoria Police absence from residence | 2 022 | 99 | Physical form to lodge (by post or in person |

| Victoria Police Partysafe (register your party online) | 6 552 | 99 | ||

| Housing and property | Apply for the Solar Homes rebate | 62 544 | 99 | None |

| Outdoor and recreation | Buy a fishing licence | 170 320 | 75 | In person (at a retailer), or by requesting a form to lodge with the Victorian Fisheries Authority |

| Buy a miner’s right | 4 779 | 60 | Via an agent | |

| Find a kangaroo harvester | 1 419 | 99 | None | |

| Personal | Ambulance Victoria new membership | 1 775 | 1 | Digitally via Ambulance Victoria's website, by phone or in person |

| Ambulance Victoria update membership | 1 316 | 1 | ||

| Ambulance Victoria membership renewals | 2 621 | Less than 1 | ||

| Transport and driving | VicRoads check registration | 346 739 | 40 (increased in July 2020)* |

Digitally via Department of Transport’s website |

| VicRoads renew registration | 85 815 | 1 (increased in July 2020)* |

Digitally via Department of Transport’s website, by phone or in person | |

| Boat registration renewals | 572 | Less than 1 | ||

| Work and volunteering | WWCC new application | 373 | Less than 1 | Via WWCC website with identity verification at Australia Post |

| WWCC renewal | 8 372 | 10 (increased in September 2020)* |

Via WWCC website but only with a MyCheck account | |

| WWCC update details | 31 002 | 33 | ||

| WWCC change from volunteer to employee | 2 350 | 5 (increased in September 2020)* |

||

| WWCC teacher's notification | 4 626 | 99 | None (but a small number may approach WWCC Victoria direct) | |

| Total SV customer- facing transactions | 17 Services | 733 197 | ||

| Non-customer facing transactions | Transaction volume delivered in 2019-20 |

|---|---|

| Kangaroo tag scans | 30 121 |

| Solar Homes identity verification scans | 50 964 |

| Total transactions delivered 2019–20 | 814 282 |

Note: The three Ambulance Victoria transactions are not currently available on SV’s website as Ambulance Victoria is updating its technical systems.

Note: We list the channel mix for services that are only available via SV as 99 per cent. This allows for a small volume of transactions that customers may complete outside of the agency options provided.

Note: The percentage of transactions delivered by SV are based on SV data that forecasts the 2019–20 total agency volume.

Note: * these agencies have agreed to 'ramp up' or transfer 100 per cent of their digital transactions to SV.

Source: VAGO analysis of SV data.

Between 1 July and 31 December 2020, SV delivered five customer-facing transactions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It generated QR code posters, QR check-ins, border permits and exemptions, and the regional travel voucher scheme.

SV's quick establishment of these transactions shows its ability to build on and utilise its technology. For example, SV established online applications for regional travel vouchers in 2.5 days.

This has resulted in significant growth in the volume of transactions delivered, with 2.57 million transactions delivered in six months. However, the longevity of services delivered in response to COVID-19 and their financial value is not yet clear.

SV does not have a clear definition of a how it counts a service or a transaction. For example, SV counts each generation of a QR poster as a transaction. A business may print multiple posters to display at their premises; however, this should count as one transaction as only one QR code is generated. SV also includes non-customer-facing transactions (such as kangaroo tag scans and verification of solar installation scans) in its transaction count but does not count transactions for other services such as 'white label' transactions.

White-label transactions

Agencies can also use SV to deliver part of a transaction or service. These transactions are hosted on an agency website but use SV technology (such as online identity verification) for part of its transaction. SV calls these ‘white-label transactions’. As at 31 December 2020, SV delivered white-label services for:

- Residential Tenancies Bond Authority

- the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (for its Melbourne Strategic Assessment program)

- WorkSafe Victoria.

SV does not count the number of transactions delivered for white-label services in its transaction volume.

Factors affecting channel mix

Channel mix reflects the percentage of customers who transact face-to-face, by phone, mail or online. SV aims is to get more customers transacting online rather than using higher-cost methods.

SV needs more customers to transact digitally for it to realise its expected cost benefits. Several factors can affect the decision of a customer to transact digitally, such as:

- the complexity of the transaction

- alternatives offered by agencies (such as their own online services as well as face to-face, phone or mail)

- customer preferences.

If SV was the sole provider of all transactions for the 17 established end-to-end services it offered in 2019-20, it would have processed approximately 14 million transactions per year. SV processed about 6 per cent of this number in 2019–20.

Agency onboarding and referrals

When onboarding with SV, an agency that already has a digital channel may decide to automatically redirect a percentage of its customers to SV’s portal.

The rate at which agencies have elected to redirect (or 'ramp up') has varied:

- Some agencies, such as Solar Victoria and the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions, have redirected 100 per cent of digital transactions to SV.

- Others, such as WWCC Victoria, have progressively increased their redirection rate.

- VicRoads has been slow to ramp up. It was not until June 2020 that VicRoads agreed to:

- increase its rate of referral of transactions delivered by SV (renew and check registration)

- put the SV referral button on relevant VicRoads webpages. This is a button with SV branding that directs a customer to the transaction on SV's website.

In cases where SV is not the sole provider of the digital transaction (such as VicRoads, Ambulance Victoria and WWCC transactions), agencies run their own ICT systems, websites, customer service centres and phone lines. This means they are not realising savings through rationalisation of technology and system efficiencies. We discuss this further in Chapter 3.

2.3 SV transaction cost

Non-digital transactions are more expensive to provide than digital transactions. In 2014, DPC engaged a consultant to estimate how much transactions were costing the Victorian Government and what percentage of people were completing transactions digitally.

Around the same time, Deloitte Access Economics looked at the economic benefits of digitising customer transaction services for federal and state government departments. While this work was not specific to Victoria, it suggested that the savings from moving transactions online could be even more pronounced than the Reform Program business case estimated, with digital transactions dropping to 40 cents per transaction. We reflect the business case estimates in Figure 2E.

FIGURE 2E: Benchmark costs per transaction and channel mix (2015)

| Channel | Reform Program business case estimate | |

| Transaction mix | Cost per transaction estimates | |

| Face-to-face | 32% | $21.52 |

| 24% | $30.22 | |

| Phone | 12% | $13.21 |

| Online | 32% | $6.84 |

Source: Reform Program business case.

Marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when one additional unit is produced.

Variable costs are a corporate expense that increase or decrease depending on the production output.

SV calculates transaction costs by dividing its total running cost by the volume of transactions delivered. The marginal cost of onboarding new services is low. As SV increases its volume, its per unit transaction cost will decrease, assuming that its variable costs do not scale up with volume.

However, there are limitations to this calculation. It does not reflect SV's direct or indirect operational costs, nor does it reflect the complexity of the transaction. Further, if SV delivers one simple, high-volume transaction (such as QR scans), this will skew the transaction cost despite the transaction requiring very limited customer interaction.

As shown in Figure 2F, in 2019–20 SV was expensive compared to similar services.

FIGURE 2F: SV's cost per transaction compared to other services

Note: Service NSW’s costs are estimated based on the cost to deliver Service NSW and its transaction volume. It includes transactions conducted in person at a service centre. At year five of Service NSW (the same stage of development as SV), the cost per transaction was $26.

Note: The average cost of digital transactions in Victoria is from the Reform Program business case.

Source: SV data, Reform Program business case and publicly available information.

Between 1 July 2020 and 31 December 2020, SV introduced COVID-19 transactions. Including these transactions significantly changes the cost per transaction amount as shown in Figure 2G.

FIGURE 2G: Impact of COVID-19 transactions on SV's cost per transaction

| Between 1 July 2020 and 31 December 2020 SV delivered … | Inclusion of these transactions using SV's method results in a cost per transaction of … |

|---|---|

| 0.60 million transactions from its existing services | $34.62 |

| Plus 0.53 million new COVID-19-related transactions (excluding QR scans and posters only) | $18.39 |

| Plus 1.44 million QR scan and poster generation transactions | $8.09 |

Source: VAGO, based on SV data.

2.4 Customer benefits

DPC's Reform Program business case highlighted that digital reform would make it quicker and easier for customers to undertake transactions and improve customer satisfaction.

SV has consistently achieved high customer satisfaction results for the transactions it delivers.

Measuring customer satisfaction

Customer feedback provides important insights into SV’s products and services and helps it identify any problems.

DPC’s Measure how content performs—digital guide describes what better practice for digital services involves. It states that:

- at a minimum, a service should invite customers to give feedback once they reach the page that confirms a successful transaction

- a more robust approach is to capture data on people who abandon a form part way through the process.

The Victorian Government does not have a prescribed approach for measuring customer satisfaction. This means that agencies can choose their preferred methodology to calculate it.

The BP3 outlines the government's priorities for the delivery of services, its performance targets and whether it is achieving these.

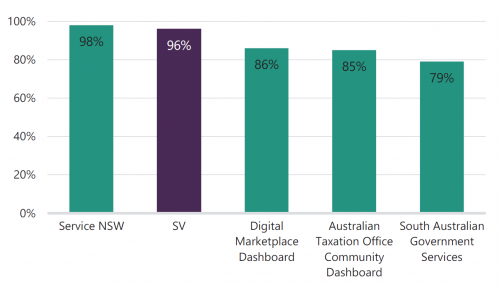

Customer satisfaction is SV‘s only BP3 measure, and it has set itself a high target of 95 per cent satisfaction. SV reported that it achieved its target for both 2018–19 (97 per cent) and 2019–20 (96 per cent). Between 1 July and 31 December 2020, SV reported that it achieved 96.7 per cent satisfaction.

SV does not ask all customers for their feedback but uses a sample to determine customer satisfaction with its service. When an SV customer completes a transaction, they may be offered an option to provide feedback on a five-point scale from ‛great experience‘ to ‛I'm not happy‘. SV then calculates customer satisfaction by using the median responses of the 3, 4 and 5 ratings.

Figure 2H compares SV’s customer satisfaction rate to that of other digital transactions and services.

FIGURE 2H: Customer satisfaction scores for a sample of digital services and transactions

Note: It is unclear how Service NSW and the South Australian Government Services channels measured customer satisfaction levels.

Note: The Australian Taxation Office calculates its customer satisfaction rate using ‘satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’ responses. Digital Marketplace asks respondents to score the average level of difficulty from ‘easy’ (100), ‘OK’ (50) and ‘difficult’ (0) and produces an average.

Source: 2019–20 SV data, myGov performance dashboard (accessed August 2020), Service NSW’s Annual report 2018–19 and the 2019 South Australian Customer Satisfaction Measurement Survey.

Since its establishment, SV has used the same metric and methodology for measuring customer satisfaction. It uses this approach so it can compare its results with other similar jurisdictions. SV counts people who gave a score of 3 (OK, I guess) as satisfied.

SV's calculation approach can impact the overall customer satisfaction ratings:

|

If SV had used ratings of … |

Then its 2019–20 customer satisfaction score would be … |

Instead of … |

|

3, 4 and 5 to calculate the average value instead of a median value |

95 per cent |

96 per cent |

|

4 and 5 to calculate the average value (the common CSAT approach) |

82 per cent |

While using the CSAT approach would result in a lower customer satisfaction score, this measure is usually also associated with a lower target (75 to 80 per cent).

Other methods of gauging customer satisfaction

Sentiment analysis is a technique that is used to interpret subjective text and written commentary. For example, it looks at the words used and classifies the statement or review as positive, negative or neutral.

In addition to its externally reported customer satisfaction metric, SV also:

- internally monitors scores of only 4s and 5s, which it calls its ‛happiness score’

- analyses written feedback from customers using sentiment analysis.

SV's sentiment analysis suggests that the most commonly used word for customers who leave written feedback is ‛easy’.

SV also reviews and monitors:

- error messages received by customers

- anonymised screen recordings of real customer visits to understand customer behaviour and how customers move their cursors across the screen

- the number of customer-initiated interactions, including live webchat, email, or online feedback forms

- all rating scores of 1. These are:

- opened as cases and assigned to a customer experience officer to review and resolve if possible

- reported to the Chief Customer Officer.

- customer feedback and suggestions for continuous improvement shared by staff via Yammer, SV's internal chat system. This provides visibility of complaints across the organisation and allows staff to suggest solutions.

The following case study (Figure 2I) illustrates the impact that proactively reviewing issues can have.

FIGURE 2I: Case study—VicRoads customer satisfaction with registration renewals

In 2018, SV received several negative comments on its registration renewal transaction.

SV reviewed this customer feedback, including all free-text comments. It found that the most common customer complaint was the credit card transaction fee, which is a VicRoads requirement.

Some of the comments SV received were:

- ‛I have no choice but to pay by credit card and then you charge a fee. How about PayPal or direct deposit[?]’

- ‛CARD FEE ARE YOU SERIOUS?’

- ‛$5 charge just to pay using a Debit card! I’m paying $800 just for rego! This is criminal! Disgusted! I have to pay to pay? Haha, absolute joke.'

To address this issue, SV added other payment options, including BPAY.

Data shows that customer satisfaction scores relating to BPAY improved following this change. There has been no change in SV’s overall customer satisfaction score for this service, which has remained high (96 per cent).

Source: VAGO analysis from SV data.

Gaps in assessing customer satisfaction

SV’s customer satisfaction assessment does not survey customers who end a transaction before completing it. This means that SV is likely excluding some dissatisfied customers from its survey and does not receive their reason for not completing the transaction.

This is supported by the feedback received on SV's app, available via Google Play and the Apple App Store.

Between January 2019 and December 2020, 87 people had reviewed SV’s app with a weighted average of 2.7 stars.

As shown in the examples in Figure 2J, most reviews relate to the app’s lack of services or the information it can store. SV does not respond to these reviews.

FIGURE 2J: Customer reviews of SV's app in Google Play and the Apple App Store

‘Doesn't Store Anything You Already Have. You essentially have to renew or pay your rego or ambulance cover or working with children check just to get access. This app isn't for easy legitimate storage of your existing permits and licenses. Waste of time at the moment, hopefully they … do it right.’

‘Very easy to QR check in. Remembers my details. Nice one, gov peeps!’