Student Completion Rates

Overview

The completion of Year 12 or equivalent is an important predictor of future health, employment and welfare prospects and improves the ability of Victorians to participate socially and economically in their community.

Despite a significant focus on addressing student completion rates over the past decade, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has not significantly improved the number of students achieving Year 12 or equivalent. This lack of improvement is more stark for disadvantaged and at risk cohorts such as non-metropolitan and low socio-economic students.

DEECD’s programs to support students at risk of disengaging from education have failed to make a significant impact on completion rates and DEECD does not know whether these programs are being delivered efficiently and effectively or if schools have sufficient resources to address vulnerable student's needs.

While the decision to cease funding Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) coordinators in schools will save the government $12.3 million per year, DEECD does not know how much it actually costs schools to deliver VCAL or whether schools can meet the demand for it. The impact of any reduction in the availability or breadth of VCAL course offerings is most likely to impact on students from rural or disadvantaged backgrounds.

The information provided to decision-makers regarding the decision to cease the VCAL coordinator funding was incomplete and was not evidence based. DEECD did not use adequate processes to anticipate the compounding impact of multiple changes affecting VCAL. There are concerns about DEECD’s ability to provide comprehensive, informed advice to decision-makers to improve student completion rates.

Student Completion Rates: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2012

PP No 200, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Student Completion Rates.

Yours faithfully

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

28 November 2012

Audit summary

Educational attainment is an important predictor of a citizen's future health, employment and welfare prospects—and it improves their ability to contribute socially and economically in the community.

In Victoria, all eligible people up to the age of 19 are entitled to a government‑funded education, and those who are aged between 15 and 19 years are also entitled to a government-subsidised training place if they are not enrolled at school.

This audit reviewed whether the support provided to students to complete their schooling to Year 12 or equivalent was effective. It also reviewed whether strategies, programs and initiatives developed and implemented by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) have increased the number of 19‑year‑olds completing a Year 12 or equivalent certificate.

Conclusions

DEECD has failed to significantly improve student completion rates in the past 10 years. It did not meet the government's Growing Victoria Together target and is unlikely to meet completion rate targets set through the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions. Victoria's completion rates have not improved since 2008.

DEECD did not provide comprehensive evidence-based information to decision-makers to inform recent funding changes to the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) and Vocational Education and Training in Schools (VETiS) programs. Important commissioned research was ignored, and stakeholders, including schools, were not consulted about the likely impact of the changes. DEECD did not have sufficient evidence to assess the impact of funding changes on schools' ability to meet the growing demand for VCAL, and, in turn, on the impact that this would have on future completion rates.

Although some schools may be able to absorb the costs of the recent policy changes, DEECD has not consulted widely enough or appropriately modelled the impact of these changes to conclude this definitively. There is a risk that VCAL course offerings will become restricted in the future.

The issues highlighted in this audit relating to DEECD’s advice on VCAL raise broader concerns about its ability to gather and use sufficient evidence to assess the potential impact of policy changes and provide comprehensive, informed advice to decision‑makers to improve student completion rates.

DEECD has a range of strategies for schools to assist students to complete Year 12 or equivalent. However, these are no longer improving student completion rates. Further, these strategies have never substantially improved completion rates for students from non-metropolitan and low socio-economic status areas, who have lower completion rates than the Victorian average.

There is no systematic or coordinated strategy around the program and curriculum offerings, and program implementation across schools varies considerably.

DEECD does not collect data that could be used to analyse outcomes of current practices and model the impact of changes to the system. Without data to analyse what works and why, DEECD cannot make this information available to schools to facilitate their making more informed choices about which programs to implement or cease.

Findings

Completion rates

In 2005, the Growing Victoria Together framework set a target that by 2010, 90 per cent of 20- to 24-year-old students would have completed Year 12 or equivalent. In 2010, 88.1 per cent of students had completed Year 12 or equivalent.

It is unlikely that Victoria will meet the completion rate target of 89.35 per cent by 2012, set by the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions.

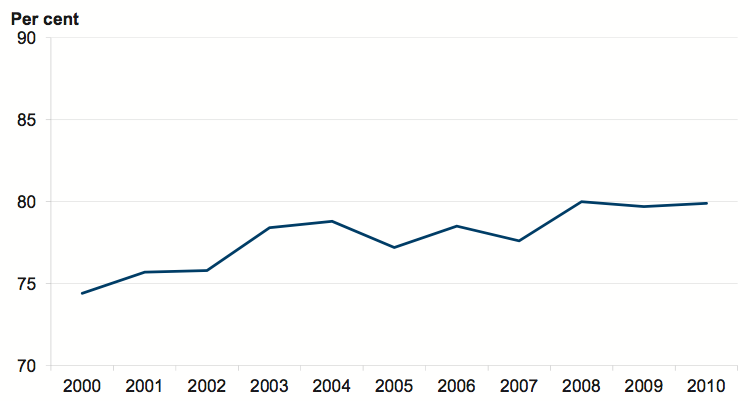

The proportion of 19-year-olds completing Year 12 or equivalent in Victoria plateaued at around 80 per cent in 2008 and has not improved since.

Students in non-metropolitan schools and students from a low socio-economic background have a lower Year 12 or equivalent completion rate than the Victorian average. The completion rate for non-metropolitan students has deteriorated since 2006 and the gap between metropolitan and non-metropolitan schools is growing. The completion rate for low and medium socio-economic status students has also been decreasing over this time and the gap is widening in comparison to high socio-economic status students.

Strategies to improve student completion rates

There are four program categories to assist disadvantaged and vulnerable students to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent.

The programs generally target the same cohort of at-risk students, but vary in relation to how the programs are delivered in individual schools.

Schools judge some programs as valuable in engaging at-risk students. However, programs do not have clearly identifiable goals or measures to allow program effectiveness to be measured or compared. DEECD does not monitor or evaluate programs to analyse how—or whether—they have supported students to remain engaged at school. There is, therefore, no evidence that these programs are positively impacting on completion rates.

DEECD does not coordinate programs, advise schools about which programs would work best in particular circumstances, or tell them what outcomes are likely for students. Without this information and guidance, schools cannot make informed decisions about which curriculum and program offerings will best suit the needs of their communities.

Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning

The uptake of VCAL has risen steadily since it was introduced in 2002, and an increasing number of young people are completing a VCAL certificate at an intermediate and senior level.

In 2011, 13 858 government school students were enrolled in VCAL, an increase of 60 per cent since 2006. In 2010, 87 per cent of intermediate or senior VCAL students entered the workforce or went into training or further education. However, VCAL has not improved Victoria's completion rates or retention rates.

As a proportion, more students with identifiable and measurable risk factors related to completing school—such as low socio-economic status and low academic achievement—undertake VCAL as a senior secondary qualification.

There have been significant funding changes to VCAL and VETiS in recent times, which potentially reduce VCAL as a viable option for schools and students to attain a secondary school certificate. Because DEECD is not well informed on the likely consequences of these changes, it cannot anticipate their impact on VCAL and VET (a compulsory component of intermediate and senior VCAL). DEECD has failed to provided comprehensive, evidence-based advice to decision-makers on this critical issue.

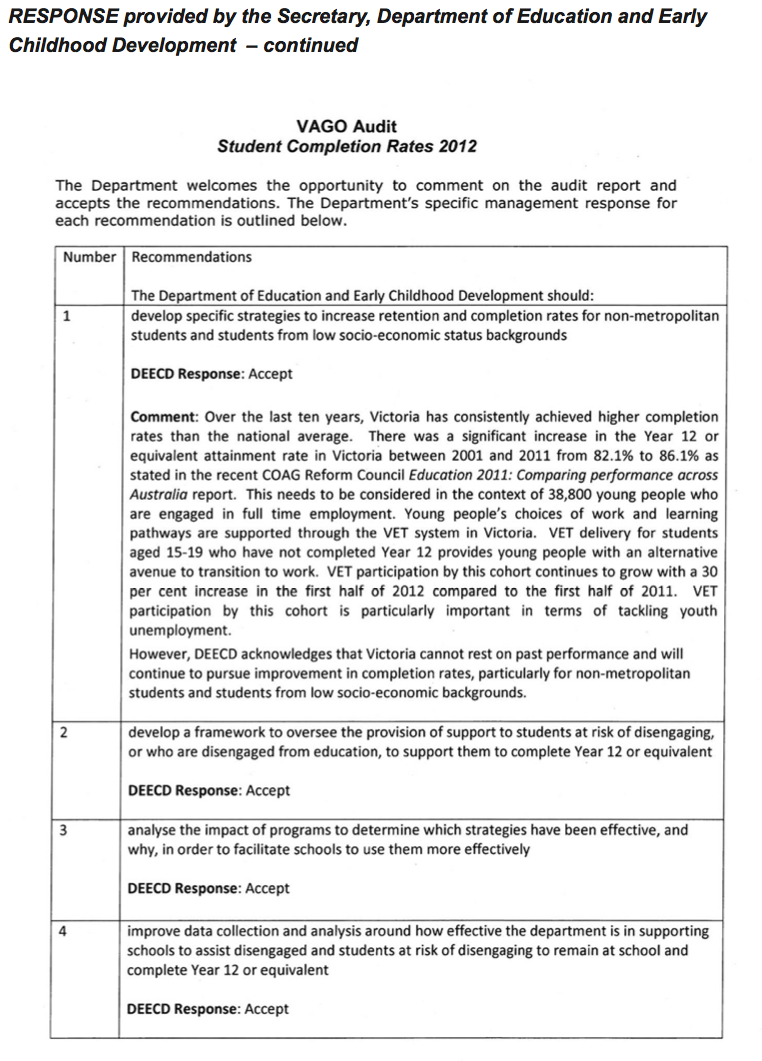

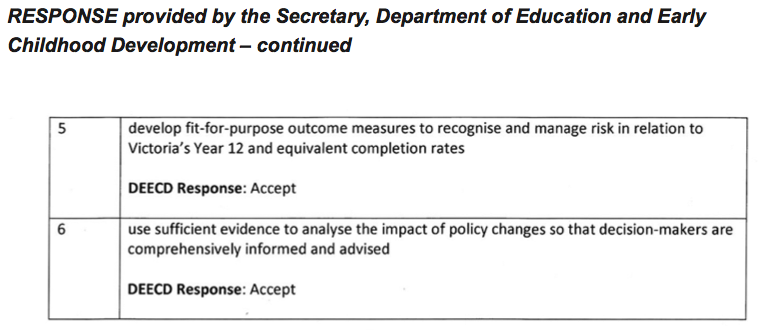

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop specific strategies to increase retention and completion rates for non-metropolitan students and students from low socio-economic status backgrounds

- develop a framework to oversee the provision of support to students at risk of disengaging, or who are disengaged from education, to assist them to complete Year 12 or equivalent

- analyse the impact of programs to determine which strategies have been effective, and why, in order to facilitate schools to use them more effectively

- improve data collection and analysis around how effective the department is in supporting schools to assist disengaged students and those at-risk of disengaging to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent

- develop fit-for-purpose outcome measures to recognise and manage risk in relation to Victoria's Year 12 and equivalent completion rates.

- use sufficient evidence to analyse the impact of policy changes so that decision-makers are comprehensively informed and advised.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Educational attainment is an important predictor of future health, employment and welfare prospects and improves the ability of Victorians to participate socially and economically in their community.

Students' educational outcomes, including their completion rates, are influenced by many factors including their social and economic background, their family situation, their engagement with education, and personal qualities such as resilience and self‑confidence. While some of these factors sit outside the sphere of influence of schools, many are directly influenced by the school environment. The negative impacts of others can be offset by the use of appropriate strategies in schools.

This audit reviewed whether the support provided to students to complete their schooling to Year 12 or equivalent is effective and whether strategies, programs and initiatives developed and implemented by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) have increased the number of young people completing Year 12 or equivalent.

1.2 Legislation and policy

1.2.1 Education and Training Reform Act 2006

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (the Act) provides the legislative framework for education and training in Victoria. A key principle of the Act is that all young Victorians, irrespective of the education and training institution they attend, where they live, or their social or economic status, should have access to a high quality education. This includes access to a free government education for all young people up to the age of 19.

The Act requires all students up to the age of 17 to be engaged in one of the following for a minimum of 25 hours per week:

- school

- approved other education or training such as TAFE courses, traineeships and apprenticeships

- full-time paid employment

- a combination of the above, including part-time employment.

1.2.2 Victorian policy

In 2005, the government's Growing Victoria Together policy set a target that by 2010, 90 per cent of young people in Victoria aged 20 to 24 years would have completed Year 12 or equivalent. This target was never achieved and its relevance and appropriateness was never reviewed. It has since been superseded by new, similarly ambitious, targets which Victoria agreed to under the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions.

DEECD also measures the percentage of 19-year-old students who complete Year 12 or equivalent. This information is used as a lead indicator for the 20- to 24-year-old measure. In 2010, the completion rate for 19-year-olds was 79.9 per cent.

1.2.3 National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions

Victoria is a signatory to the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions agreement (2009) (NPYAT). The NPYAT aims to increase participation by young people in education and training, attainment levels and successful transitions from school.

Under the NPYAT, the Victorian Government has committed to the target that 92.6 per cent of 20- to 24-year-olds will have attained Year 12 or equivalent certificate by 2015. This measure is derived from the ABS annual Survey of Education and Work.

Victoria and other Australian jurisdictions have concerns about the unreliability of the ABS data, including data errors and the small sample size. DEECD has advised that the Commonwealth is leading work to develop solutions to these issues.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

A key role for DEECD is the design, delivery and oversight of the Victorian education system. It manages, coordinates, implements and oversees government school education in Victoria and is responsible for delivering educational outcomes.

It also funds, either directly or indirectly, a range of programs and interventions designed to meet the individual learning needs of all students in government schools.

1.3.2 Government schools

The delivery of educational services has been reformed over the past decade. Schools are expected to respond to the needs of their local communities and deliver tailored solutions which cater for the range of students in their community.

Each school is responsible for deciding how to support students, including those at risk of disengaging from school. DEECD requires schools to deliver services and programs that cater for the specific needs of their community from within their annual school budget.

DEECD's School Accountability and Improvement Framework (SAIF) articulates three ongoing requirements of government schools against which they are annually assessed:

- improved student learning

- enhanced student engagement and wellbeing

- successful transitions and pathways.

DEECD is currently developing a ‘compact’ or agreement to be co-signed by government schools. The compact will set out the respective roles and responsibilities of DEECD and government schools within the current policy context of professional trust, autonomy and local service delivery.

1.4 What is completion?

1.4.1 The Senior Secondary School Certificate

For the purposes of this audit, student completion is defined as the rate of 19-year-olds who attain a Year 12 or equivalent certificate. This measure is stated by DEECD to be more reliable data than the NPYAT data relating to 20- to 24-year-olds.

In addition, the completion rate for 19-year-olds is a lead indicator for the 20‑ to 24‑year-old target.

The senior secondary school certificate can be achieved through the attainment of:

- the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE)—the most common means of completing school

- the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) Senior or Intermediate—an alternative senior secondary certificate with an applied learning focus

- the International Baccalaureate (IB).

VET, including apprenticeships and traineeships at Certificate Level II or above, is considered to be a Year 12 equivalent.

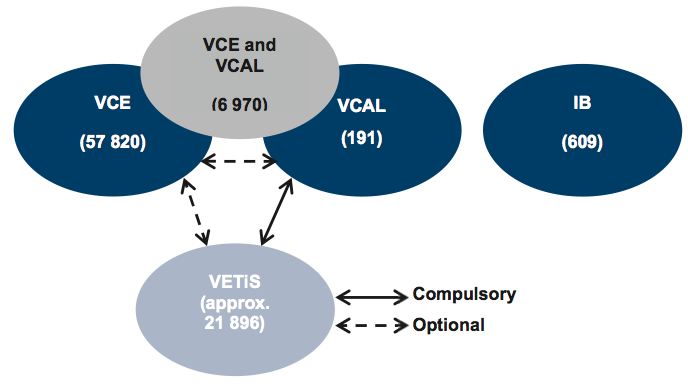

VET in Schools (VETiS) provides students with broader curriculum options that contribute to completion of Year 12 or equivalent. VETiS subjects may be taken as part of the VCE and are a compulsory part of senior and intermediate VCAL. Figure 1A outlines the senior secondary school certificate pathway options available to students in Victoria.

Figure 1A

Senior secondary certificate pathway options for 19-year-olds showing 2011 enrolment numbers

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

1.4.2 Why does completion matter?

When young people do not complete a Year 12 certificate or its equivalent, they risk serious lifetime social and economic disadvantages. There is a positive correlation between increased individual learning and a reduction in the risk of future unemployment and long-term social and economic disadvantage.

In 2007, the Education Foundation Australia report Crossing the Bridge: Overcoming entrenched disadvantage through student-centred learning identified that young people who disengage from education early are almost four times more likely to report poor health, have mortality rates up to nine times higher than the general population and are more likely to require welfare support and government-subsidised services.

The report estimates that:

- the consequences of early school leaving and lower levels of education, costs Australia $2.6 billion a year in higher social welfare, health and crime prevention

- an early school leaver can expect to earn approximately $500 000 less during the course of their working life than someone who completes schooling to Year 12.

Similarly, in 2011, the ABS Social Trends Survey identified that Australians aged 20 to 64 years were more likely to be employed if they had attained Year 12 than those who had not.

1.4.3 Funding

From July 2009 to December 2013, the Commonwealth funded Victoria $135 million for initiatives to improve retention, completion and successful transition from school. The NPYAT set a target for 24-year-olds to achieve a Year 12 or equivalent attainment rate of 92.6 per cent by 2015 in Victoria.

A further $25 million was available through the Commonwealth in reward funding on achievement of participation and attainment targets. To date, Victoria has been assessed as having achieved 89 per cent of its participation target, qualifying it for $11 million in reward funding. Its performance in future assessments will inform the proportion of the remaining reward funding it receives.

Further to the NPYAT funding, the Victorian Government has provided $29.2 million over the 2010–13 period as targeted funding through the annual budget mechanism to address aims that include student completion.

1.4.4 Who is at risk of disengaging?

There are a range of characteristics and behaviours that have significant predictive value for a student being at risk of early school leaving. These include observable risk indicators such as individual achievement associated with:

- lower socio-economic status

- geographic location

- gender

- families under stress

- living in neighbourhoods of high poverty or in remote locations

- risk of homelessness

- Indigenous background

- ethnicity.

Risk indicators also include student behaviours such as:

- low academic achievement

- conflict with teachers

- poor attendance.

1.5 Other measures of educational success

Completing Year 12 or equivalent is an obvious and easy-to-measure indicator of success in education.

However, for every year that a student remains engaged with the education system they also gain social skills, mature and become better able to participate fully in society as an adult, either through pursuing further education and training and/or participating in the workforce.

Therefore, it is also important to measure how long students remain in school (retention) and where they go when they leave school (destination).

1.5.1 Measuring retention

Student retention is most commonly measured as the number of students who remain in school at a given point in time as a percentage of the number in that cohort who started. In Australian schools, retention is measured as the number of Year 12 full-time equivalent students expressed as a percentage of the number of Year 10 full-time equivalent student enrolments two years earlier.

For example, if a school had 100 Year 10 students in 2010 and only 50 Year 12 students in 2012, the retention rate would be 50 per cent.

Published retention rates do not account for inter-sector, interstate or repeating students.

1.5.2 Assessing destinations

DEECD's annual On Track survey report Destinations of School Leavers analyses the destinations of Victorian students shortly after they leave school.

This analysis includes destinations by gender, year level, socio-economic status and regional areas; reasons for not continuing in education and training; and details on employed school leavers' occupations and hours worked.

1.6 Students requiring support to complete Year 12 or equivalent

Students have diverse needs, with different learning profiles and rates of learning. Although the majority of students at school do not require programmatic support, many students will encounter some difficulty during their school life. DEECD has developed or endorsed a range of programs to address these challenges.

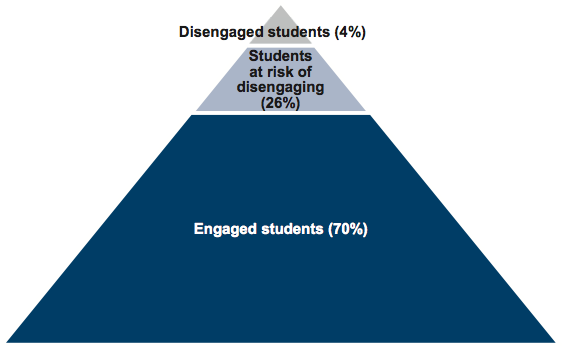

Many of these programs are aimed at students who are at risk of disengaging from school. A much smaller number of students will have already disengaged from school and will require help to re-engage in formal education. DEECD does not measure the number of students that are at risk of disengaging and does not know how many young people have actually disengaged. In the absence of such information, we have estimated the proportions using current reports on disengaged students as identified in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Proportion of students requiring support

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, using data from Department of Education and Early Childhood Development-commissioned reports.

Given the importance of completing Year 12 or equivalent, the proportion of students at risk of disengaging from education, and the proportion of students who have disengaged from the education system, it is imperative that DEECD has a comprehensive strategy to support students to remain engaged and complete Year 12 or equivalent.

DEECD uses a lead indicator of completion rates for 19-year-olds which allows it to gauge the success of its policies and strategies in order to meet NPYAT requirements of 20- to 24-year-old completion.

1.7 Audit objective and scope

The objective for this audit was to assess whether DEECD's strategies, programs and initiatives to support students to complete Year 12 or equivalent are effective.

The audit considered whether:

- DEECD has a clearly defined and researched approach to supporting students who are at risk of disengaging or have disengaged to complete Year 12 or equivalent

- programs to support students to complete Year 12 or equivalent have been implemented effectively and are improving school completion rates

- DEECD monitors and evaluates programs and uses this information to inform future program planning and funding to increase Year 12 or equivalent completion rates.

The audit included:

- analysis of relevant student completion data from 2006 to 2011 to identify trends

- discussion with DEECD central office staff and visits to two DEECD regional offices

- visits to eight secondary or P–12 schools in each of the two visited DEECD regions, including interviews with:

- the principals, lead teachers and teachers involved in programs and processes to support students to complete school

- student wellbeing staff, year-level coordinators, career advisors, and staff involved with flexible or alternative learning options.

1.8 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted under section 15 of The Audit Act 1994, and was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Total cost of the audit was $395 000.

1.9 Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 identifies student completion rates and outcomes for Victoria.

- Part 3 examines the effectiveness of DEECD's programs to support vulnerable and disadvantaged students to complete Year 12 or equivalent.

- Part 4 examines DEECD's role in relation to managing the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning.

2 About student completion rates

At a glance

Background

In 2005, the government's Growing Victoria Together policy set a target that by 2010, 90 per cent of young people in Victoria aged 20 to 24 years would have completed Year 12 or its equivalent. The relevance and appropriateness of this target has not been reviewed since it was initially set in 2005.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) also measures the percentage of 19-year-old students who complete Year 12 or equivalent. This information is used as a lead indicator for the 20- to 24-year-old measure.

Conclusion

Despite a significant focus on addressing student completion rates over the past decade, DEECD has not significantly improved the number of students achieving Year 12 or equivalent. This lack of improvement is more stark for disadvantaged and at‑risk cohorts such as non-metropolitan and low socio-economic status students. Further, it is likely to prevent DEECD from gaining full bonus payments under the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions agreement.

Findings

- There has been no significant improvement in Year 12 or equivalent completion rates for 19-year-old students since 2008.

- Victoria is not expected to fully meet its agreed targets under the National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions agreement and therefore is unlikely to be eligible for the full additional funding to support this target.

- Students from lower socio-economic and non-metropolitan schools have poorer Year 12 or equivalent completion rates than students from higher socio-economic and metropolitan schools.

Recommendation

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should develop specific strategies to increase retention and completion rates for non-metropolitan students and students from low socio-economic status backgrounds.

2.1 Introduction

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development's (DEECD) mission is to develop ‘a high-quality and coherent birth-to-adulthood learning and development system to build the capability of every young Victorian’.

Key to achieving this objective is making sure that children are engaged in education and are transitioning successfully from school to further education or work.

2.2 Conclusion

DEECD has failed to significantly improve completion rates in Victoria and indications are that completion rates have plateaued below target levels.

Victoria has not met, and is not likely to meet, its targets for 20- to 24-year-old students, placing future National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions (NPYAT) funding at risk. The completion rate for students in this category has risen by less than 4 percentage points in the past 10 years, a trend mirrored by national results.

Similarly, there have been only marginal improvements to the completion rate for 19-year-old Victorian students in the past 10 years, and no improvement since 2008. Critically, completion rates for both non-metropolitan and low socio-economic status (SES) students in government schools are well below the state average and are declining.

2.3 Student completion rates for 20- to 24‑year‑olds

In 2005, the government's Growing Victoria Together policy set a target that by 2010, 90 per cent of young people in Victoria aged 20 to 24 years would have completed Year 12 or its equivalent. In 2010, Victoria’s completion rate for this cohort was 88.1 per cent, up from 86.1 in 2007. The 90 per cent target was never achieved and no longer applies.

NPYAT, to which Victoria is a signatory, sought to:

- increase the participation of young people in education and training

- ensure that young people make a successful transition from school to further education, training or full-time employment

- increase the attainment rate of young people aged 15 to 24 years, including Indigenous youth.

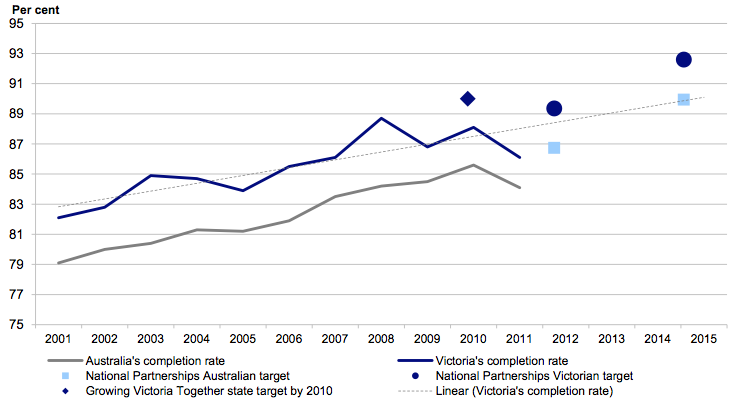

In 2007, the national completion rate was 83.5 per cent. NPYAT set a national target of 90 per cent by 2015, and all states were required to improve completion rates by 6.5 percentage points by then. Victoria's 2015 target rate was set at 92.6 per cent.

Targets were also set for 2010 and 2012 for each state, and reward funding was made available based on these targets. Victoria's reward funding was based on a pro-rata achievement of the following:

- 2010 participation target—89.9 per cent (total per cent of students enrolled in Year 12 or equivalent)

- 2012 completion target—89.35 per cent.

In 2010 Victoria achieved 88.7 per cent of the participation target, qualifying for $11 million in reward funding. A further $13.8 million is available to Victoria if it achieves its 2012 completion target. However, it is highly unlikely that Victoria will be eligible for the remaining reward funding as its performance fell by 1.9 percentage points in 2011. DEECD acknowledges that at the current rate of increase, Victoria will not fully meet its agreed targets under the NPYAT agreement.

Figure 2A compares Victorian and national completion rates against these targets. Improvement rates in Victoria largely mirror changes in national completion rates.

Figure 2A

Victorian and national completion rates (20- to 24-year-old students)

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Australian Bureau of Statistics, and National Partnership on Youth Attainment and Transitions.

Victoria has traditionally had a higher completion rate than most other states. DEECD has not done any work to understand whether this is because of good educational practice or a result of the broader economic and social context in Victoria. Nevertheless, Figure 2A shows that completion rates in other states are improving more quickly than in Victoria. If Victoria continues on the path established over the past 10 years, its lead over other states will decrease.

Figure 2A also shows that unless Victoria’s performance improves dramatically over the next four years, it will not come close to meeting its National Partnerships target and indeed is unlikely to meet the lower combined target for all states.

2.4 Overall completion rates for 19-year-olds

DEECD measures completion rates for 19-year-olds using administrative data from the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, its Higher Education and Skills Group and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. More information is available on this cohort than on the 20- to 24-year-old group, and DEECD also considers this data to be more reliable. However, while the 19-year-old completion rate is considered a lead indicator for the 20- to 24-year-old targets, DEECD has not set a target relating to this measure.

This section examines three critical, measured components of 19-year-old completion:

- completion

- retention

- destinations.

2.4.1 Completion

Overall, the proportion of 19-year-olds completing a Year 12 or equivalent qualification in Victoria increased from approximately 74 per cent in 2000 to 80 per cent in 2008. Since then there has been no improvement. Figure 2B shows the change in the percentage of 19-year-olds completing a Year 12 or equivalent qualification in Victoria since 2000.

Figure 2B

Victorian Year 12 or equivalent completion rate at age 19 years

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

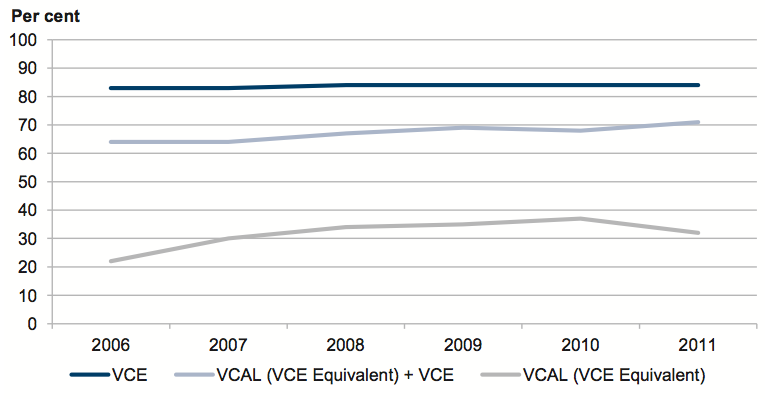

In Victoria, Year 12 or equivalent completion includes the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE), the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL), Vocational Education and Training (VET) at the Australian Qualifications Framework level II and above, and the International Baccalaureate. In addition to undertaking a straight VCE or VCAL certificate, students can also study a combination of VCE and VCAL subjects as part of either certificate. Figure 2C shows how completion rates vary according to the chosen area of study.

Figure 2C

Senior secondary certificate completion rates at age 19 years in Victorian schools, 2006–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority data.

A greater percentage of students who enrol in VCE only, go on to complete school than those who enrol in both VCE and VCAL certificates, or in VCAL only. This may reflect the fact that VCE students are generally more academically motivated and more likely to be well engaged with school.

Since 2006, completion rates for VCE only students have remained steady. In contrast, completion rates for VCE students with a VCAL component in their study have increased. Notably, completion rates for VCAL only students fell by 4.6 per cent from 2010 to 2011. There may be a correlation between this decrease and the 3.1 per cent increase of the VCE/VCAL student completion rate, as more VCAL students are undertaking the combination of certificate studies.

2.4.2 Retention

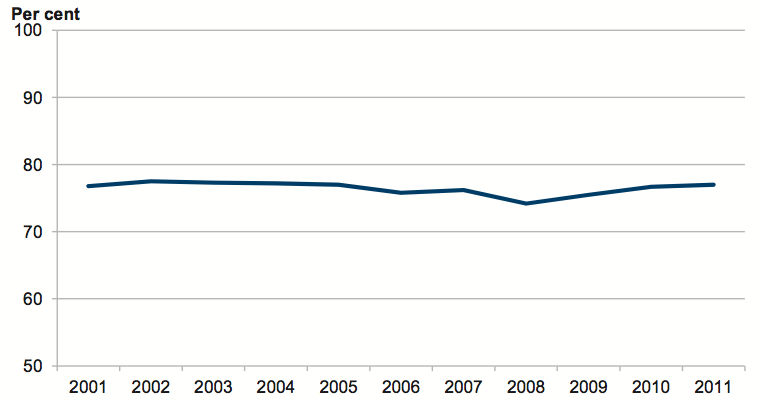

The longer a student is engaged with the education system the better their likely life outcomes. Retention measures how long students remain in school. It is most commonly assessed as the number of Year 12 enrolments expressed as a percentage of the number of Year 10 enrolments two years earlier. Figure 2D shows that the retention rate for government school students has not improved over the past decade.

Figure 2D

Year 10–Year 12 retention rate for government school students

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics Census data.

2.4.3 Destinations

Destination data shows what students choose to do when they leave school. DEECD's On Track survey is an annual study of the destinations of students who have left the school system. It provides a detailed analysis of student choices in the first six months after leaving school. On Track data includes destinations by gender, year level, socio‑economic status (SES) and regional areas; reasons for not continuing in education and training; and details on the occupations and hours worked of employed school leavers.

Between 2008 and 2011, the number of students aged 15 to 19 in government‑subsidised training who had not completed Year 12 and who did not hold qualifications of Certificate II or higher increased by 34 per cent. Almost half of these students (44 per cent) were engaged in training as apprentices or trainees in 2011 (over 25 000 students). While this participation is not yet reflected in increased overall completion rates for 19-year-olds, it is a positive lead indicator for future improvements in completions.

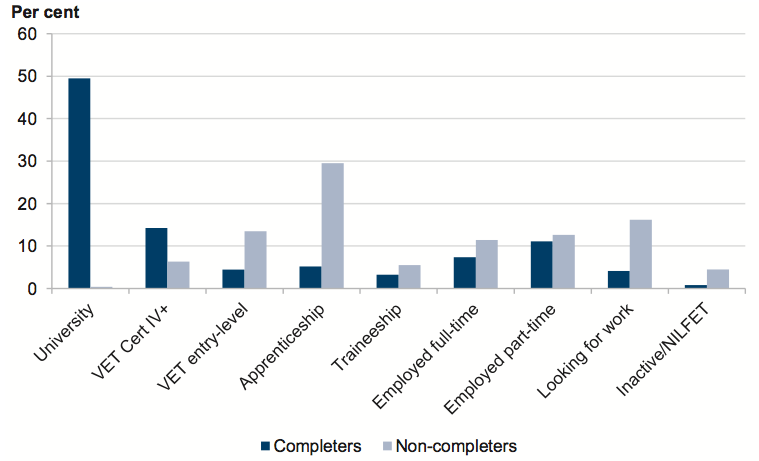

Figure 2E shows the destinations of school leavers in 2011.

Figure 2E

Overall destinations, completers and non-completers, for 2011

Note: NILFET – not in the labour force, education or training.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the 2011 On Track.

Unsurprisingly, non-completion does not allow students to go on to do a bachelor degree, whereas just under half of the students who completed Year 12 or equivalent went on to commence a degree. Thirty-five per cent of non-completers commenced an apprenticeship or traineeship, for which an entry certificate is not required, and which may begin at any time in a calendar year. A higher proportion of students who do not complete Year 12 or equivalent are more likely to be in the work force than students who complete. Nearly 29 per cent of non‑completers are either looking for work or are in part-time work which is less likely to lead to a career path. A significantly higher percentage of students who do not complete Year 12 or equivalent are not in the labour force, education or training.

2.5 Regional differences in completion rates for 19-year-olds

A 2009 inquiry by the Education and Training Committee of the Victorian Parliament, Geographical Differences in the Rate in which Victorian Students Participate in Higher Education, found geographical and socio-economic differences in completion rates. This is strongly corroborated by DEECD's more recent data, which highlights the difficulties and disadvantages faced by students in non-metropolitan parts of Victoria.

2.5.1 Completion

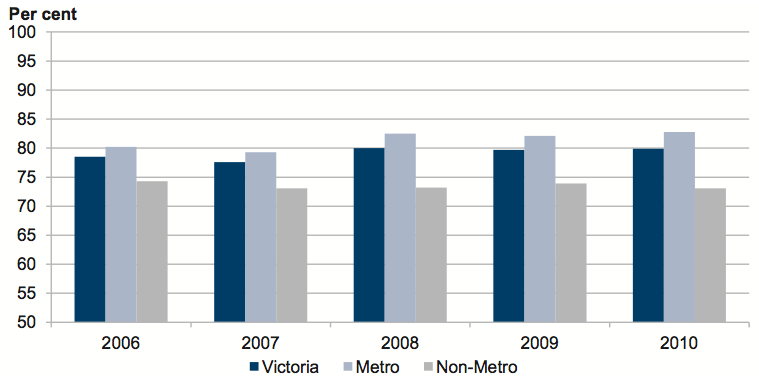

Students in non-metropolitan areas of Victoria are significantly less likely to complete school than students in metropolitan areas. Figure 2F shows the comparative completion rates for metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas of Victoria. It is clear from this that the gap not only exists but is widening. In 2010, completion rates for non‑metropolitan students were about 10 per cent lower than for metropolitan students.

Figure 2F

Government school completion rates for 19-year-olds by geographical area

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

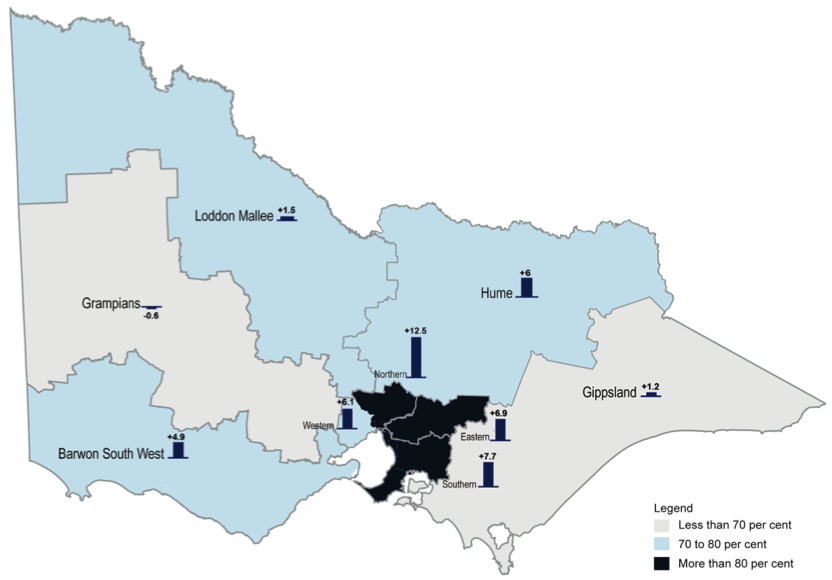

Figure 2G is a heat map which shows completion rates for each of DEECD's nine regions. Since 1999 there has been improvement of at least 6 percentage points in completion rates for students in metropolitan regions. However, this improvement rate is much lower in non-metropolitan regions, and Grampians region showed a decline.

Figure 2G

2010 Year 12 or equivalent attainment rates at age 19 by region (and percentage change 1999 to 2010)

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

2.5.2 Retention

Similarly, there is a clear difference between metropolitan and non-metropolitan students in retention rates, although the gap is not widening. Activities to improve retention rates have been ineffective, especially in non‑metropolitan areas.

2.5.3 Destination

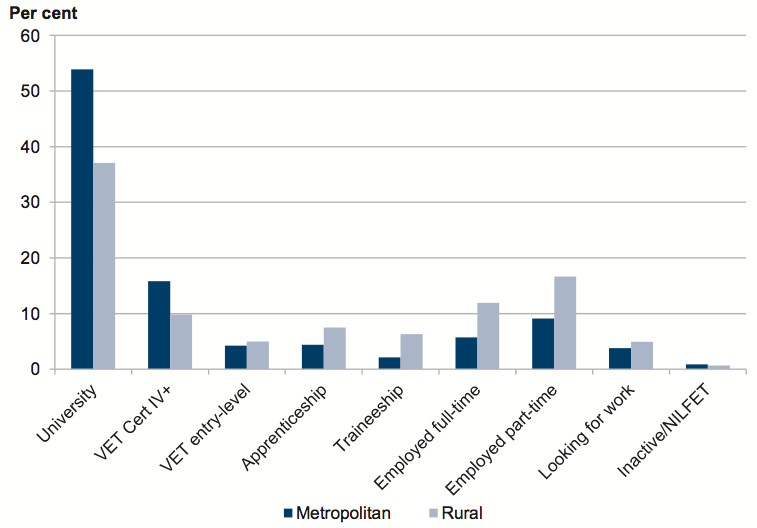

There is a difference in the destinations of metropolitan and non-metropolitan students. As Figure 2H shows, for metropolitan students who completed Year 12 or equivalent, the most common destination was bachelor degree study, attracting 54 per cent of the group, compared to 37 per cent of non-metropolitan completers. Non-metropolitan completers more commonly went straight to work from school. The difference in completion rates is clearly evident in the choices that students make after school, which may have a long‑term impact on non-metropolitan students' ability to reach their potential.

Figure 2H

Destinations of Year 12 or equivalent completers by region

Note: NILFET – not in the labour force, education or training.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from On Track 2011.

2.6 Socio-economic status differences in completion rates for 19-year-olds

2.6.1 Completion

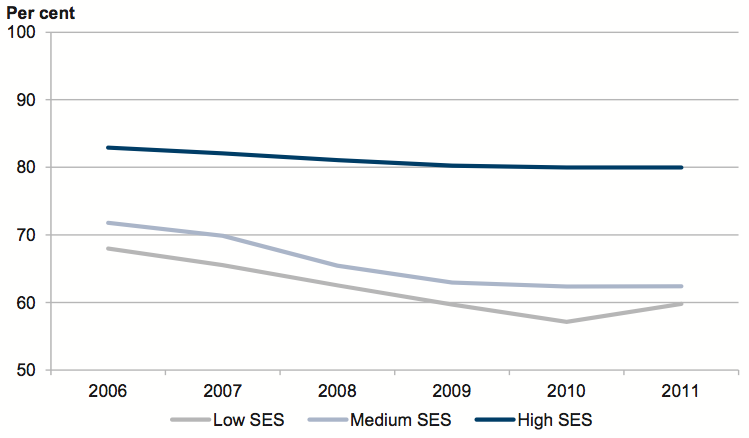

High-SES students in government schools have higher completion rates than their low‑ and medium-SES peers, as shown in Figure 2I. In 2011 the Year 12 completion rate for students from low-SES areas was 60 per cent compared to 80 per cent for those from high-SES areas. This gap has been widening over time as completion rates in low- and medium-SES areas fell more quickly than in high-SES areas between 2006 and 2010.

Figure 2I

Completion rates for 19-year-olds by socio-economic status

Note: Does not include 'or equivalent' completions i.e. VET at Certificate Level II or above.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

The 2009 inquiry by the Education and Training Committee of the Victorian Parliament recommended that system-wide school improvement strategies be implemented, with particular attention to schools in non-metropolitan and low-SES areas. There is no evidence that any strategies have improved completion rates for these two cohorts of Victorian students.

2.6.2 Retention

Research commissioned by DEECD in 2007 found a strong relationship between the performance of schools and the SES composition of their students. Students in high‑SES secondary schools obtained an average VCE result of 30.5 compared to an average score of 24.9 in schools with large numbers of low‑SES students. An acknowledged risk factor for student disengagement is poor academic performance. The poorer completion rates for low-SES students may correlate with the lower academic performance and increased disengagement.

2.6.3 Destinations

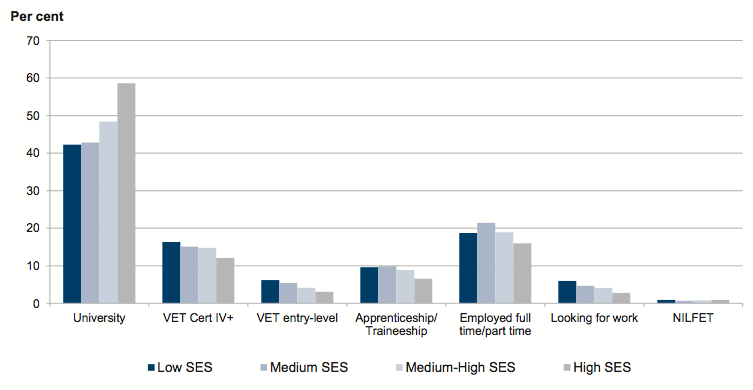

Figure 2J clearly demonstrates that students from higher-SES backgrounds are far more likely to undertake tertiary education and are less likely to undertake an apprenticeship or traineeship, or enter the workforce.

Figure 2J

Destination of completers by socio-economic status

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from On Track 2011.

There are clear differences in the destinations of high- and low-SES students. The difference in completion rates is reflected in the choices that students make after school.

The 2009 Parliamentary inquiry recommended that a statewide program aimed at raising aspirations towards higher education for students in under-represented groups (primarily non-metropolitan and low-SES) should be implemented. There is no evidence that any strategies have had a positive impact on the destinations for these two cohorts of Victorian students.

DEECD commissioned a review of the Student Resource Package in 2012 to examine the adjustments made to schools in non-metropolitan areas of Victoria and the equity supplement provided to schools serving disadvantaged communities. The review noted supplementary funding as an influential factor in affecting student outcomes in these two cohorts. It concluded that there are a number of ways the supplementary funding could be improved and more accurately targeted. DEECD has yet to respond.

Recommendation

- The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should develop specific strategies to increase retention and completion rates for non-metropolitan students and students from low socio-economic status backgrounds.

3 Strategies to improve student completion rates

At a glance

Background

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) develops and endorses programs that schools use to assist students that are disengaged or at risk of disengaging to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent. Schools are able to select which programs they offer based on their local needs.

Conclusion

DEECD’s programs to support students at risk of disengaging from education have failed to make a significant impact on completion rates. DEECD does not know whether these programs are being delivered efficiently and effectively or if schools have sufficient resources to address vulnerable students' needs.

Further, DEECD has not provided schools with the advice and guidance they need to make more informed choices about how best to support their students to remain engaged in education.

Findings

- DEECD does not have a systematic framework for accountability, quality of services and outcomes for students.

- DEECD does not collect data to evaluate the effectiveness or efficiency of programs to engage students to complete Year 12 or equivalent.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop a frameworkto oversee the provision of support to students at risk of disengaging, or who are disengaged from education, to assist them to complete Year 12 or equivalent

- analyse the impact of programs to determine which strategies have been effective, and why, in order to facilitate schools to use them more effectively

- improve data collection and analysis around how effective the department is in supporting schools to assist disengaged students and those at risk of disengaging to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent.

3.1 Introduction

Research shows that supporting students to stay at school requires an integrated, strategic approach that supports the needs of individual students. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) is responsible for delivering educational outcomes in Victoria. It funds, either directly or indirectly, a range of programs and interventions designed to meet the individual learning needs of all students in government schools.

DEECD has developed its own programs and endorses third-party programs that schools can use to assist disadvantaged and vulnerable students to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent.

Schools are free to work out which programs would best meet the needs of their students and apply them in any combination or sequence. Some of the programs are accompanied by additional funding, but generally schools must fund additional support from within their school budget.

This Part examines DEECD’s approach to assisting disengaged students to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent. It examines how programs fit together and the impact they have on each other. It also looks at specific outcomes or measures that DEECD requires to effectively monitor and evaluate these programs to ensure they are collectively having a positive impact on completion rates.

3.2 Conclusion

DEECD’s current disjointed approach to improving student completion rates is not working. Completion rates have remained static for several years and are lower in the key vulnerable demographics of students from low socio-economic backgrounds and non-metropolitan locations.

DEECD does not have a coordinated governance framework at the state, region or school network level to oversee the provision of support to disengaged students or students at risk of disengaging.

DEECD does not routinely collect and analyse the data on program inputs and outcomes that it needs to effectively monitor and evaluate programs that are designed to support vulnerable students. A more purposeful, coordinated and strategic approach is required if significant improvements are to be made to completion rates.

3.3 Re-engaging and supporting students

Keeping students engaged in education and improving completion rates across the school system is a difficult task. In a devolved environment, a shared vision, good practice principles, sound governance structures and clearly articulated accountabilities are particularly important.

While DEECD has provided schools with a range of options to support students, they appear as a disjointed patchwork of options rather than a coherent, purposeful strategy.

3.3.1 Strategic framework

DEECD has not developed a governance or accountability framework that effectively monitors the implementation and performance of programs to support students at risk of disengaging from education. Neither does it hold schools to account for the efficient and effective use of program funding, quality or outcomes.

The inherent lack of information about the programs means that DEECD cannot provide informed advice and support to schools with disengaged students or students at risk of disengaging.

In 2009, DEECD commissioned a report to develop a framework for a consistent, evidence-based approach to supporting students at risk of disengaging, or who are disengaged from school. Although DEECD undertook some work in 2010 to address the issues raised in this report, we were advised this work was not completed following the change of government. However, DEECD has provided guidance to schools about re-engagement programs that operate outside mainstream school settings, and has made changes to the Student Resource Package that allow funding for a student to be transferred from the student's original school to the receiving school.

There is no framework for supporting either students at risk or those disengaged from school.

A 2011 Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission review of Victoria’s competitiveness in ‘key areas of performance’ found that there was incomplete information on the extent of youth disengagement, which impeded the design of effective interventions. It also found the complexity and fragmentation of existing service delivery was a barrier to DEECD achieving better student engagement outcomes. The report recommended that the Victorian Government:

- develop a clearer strategy which gauges the extent of the youth disengagement problem in Victoria

- develops systems, processes and indicators for early identification and intervention

- simplifies programs and funding arrangements

- establishes evaluation and monitoring mechanisms.

DEECD has advised that the Department of Treasury and Finance was expected to prepare a whole-of-government response, but to date there has been no formal response to the review, and DEECD has not been involved in this process.

3.4 Major school strategies to increase student completion

DEECD has developed strategies that schools can use to support students to complete Year 12 or equivalent. This audit examined three strategies in detail: Managed Individual Pathways, Student Support Services (the most financially significant programs) and the Student Mapping Tool. These strategies are designed to underpin the school’s approach to identifying students who are at risk of disengaging and identifying programs to support them to stay involved in education.

DEECD states that these are successful and important strategies, but it does not require schools to use them. Since DEECD does not evaluate or analyse these strategies, it cannot determine how well they are being implemented, or whether they are collectively having the impact on completion rates that the department desires.

The overall lack of improvement points to these programs as being ineffective.

3.4.1 Managed Individual Pathways

Managed Individual Pathways (MIP) is intended to support government schools to identify and provide programs for students at risk of disengagement. However, DEECD has not collected data about MIPs to evaluate its effectiveness. DEECD cannot determine whether the funding allocated to MIPs is being used to good effect.

Government schools are provided with base funding from MIPs to support the pathway planning process for students 15 years and older. Further funds are provided through MIPs to low socio-economic status schools to support at-risk students. In 2011, schools shared $16 million, which was made up of base funding and an ‘at-risk’ amount. While all schools with eligible students received funding, the $13 million ‘at-risk’ funding was provided to 285 schools (19 per cent of all 1 539 schools).

DEECD requires schools to report on MIPs participation through the annual Mid-Year School Supplementary Census. However, DEECD does not collect or analyse any further data that would facilitate an understanding of how MIPs funding has been used by schools and what has been effective. Despite the additional funding to support students from low socio-economic backgrounds, completion rates for these students have not improved. DEECD has not assessed why this targeted funding has had no effect.

3.4.2 Student Mapping Tool

The Student Mapping Tool (SMT) was developed to support schools to effectively implement MIPs and was made available to all government schools in 2007. SMT identifies factors that have been shown to increase the risk of student disengagement and early leaving, and can be used to map the programs and initiatives being used in a school to address these factors.

DEECD only requires schools with one or more Koorie students to use SMT. It does not collect data to evaluate the effectiveness of SMT or why some schools do not use it. Figure 3A shows that fewer than half of the government secondary schools in Victoria use SMT. Independent research identified that some schools use different tools to identify at-risk students.

Each school is responsible for deciding how to support students, including those at risk of disengaging from school. However, DEECD is not routinely informed about which, if any, tools are being used and does not know whether all students are identified and targeted with additional support.

Figure 3A

Survey responses identifying the number of schools using the Student Mapping Tool to identify students who are at risk of early leaving

|

|

Yes |

No |

Blank |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2010 |

50 |

47 |

3 |

|

2011 |

46 |

50 |

4 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

3.4.3 Student Support Services

The Student Support Services program involves a broad range of professionals including psychologists, guidance officers, speech pathologists, social workers and visiting teachers. Student Support Services Officers may intervene when students have additional needs or are at risk of disengagement.

While schools have expressed concern about the availability of Student Support Services Officers, it is too early to determine whether recent policy changes to the provision model will assist schools in this regard. The Student Support Services program was covered in more detail in VAGO’s recent report Programs for Students with Special Learning Needs.

3.5 Student engagement programs

While DEECD does not have a comprehensive list of programs that schools can choose from, there are over 50 available. The programs generally fall into one of four categories and are a mix of DEECD-developed programs, DEECD-endorsed programs, and other programs schools offer.

These categories are articulated by their funding sources or delivery setting and are:

- school-arranged settings

- programs funded through the Alternative Settings Fund

- senior secondary re-engagement programs

- school—Learn Local Partnerships.

Appendix A includes a brief summary of these programs.

Schools choose which programs to use based on their local need, and can use engagement programs that are not endorsed by DEECD at their own discretion. Schools are not compelled to use any engagement strategies, even if they have low completion rates or students who are at risk of disengaging.

DEECD is not aware of the number or variety of programs that schools utilise to engage students and does not routinely collect any information on these programs, including how much a school spends on them.

3.5.1 Program coordination

DEECD does not coordinate the programs within a category, or across categories. It is therefore possible for programs to overlap and be duplicated within schools and school networks. All four program categories have some DEECD regional office involvement to provide advice to schools about specific programs.

Given the planned structural changes to DEECD’s regional offices, schools are unsure about how they will be able to access information or support for the programs offered. DEECD has not issued clear protocols for regional oversight or engagement arrangements for these programs into the future.

In 2008 DEECD published A Guide to Help Schools Increase Student Completion following requests from schools for more information on how to plan for, implement and evaluate the impact of the strategies in a school setting.

The guide provides schools with some guidelines on planning to improve student retention, and has information on how a school might approach selecting and implementing initiatives as part of an improved student retention plan. Despite this, it still falls short in several key areas. The guide:

- lists at least 50 programs or resources from a variety of organisations and sources but does not verify or validate their quality or effectiveness

- states that schools are best placed to know the dimensions of the needs of their particular students and encourages them to adapt and select resources that best suit them and their communities—however, it does not provide schools with advice on how to assess what will work for their community or individual students

- provides information on measures a school may wish to use to assess the effectiveness of the changes they put into place—however, DEECD has not attempted to collect and analyse this information at a system level.

The guide does not provide a coordinated framework of programs or give substantive advice to schools on program implementation or evaluation.

3.5.2 Program funding

The high level of school autonomy in Victoria allows schools to make wide-ranging decisions regarding the way they meet the educational needs of their community and how they manage their budgets.

However, DEECD still has a responsibility to make sure that funds are used appropriately, contribute to planned objectives and deliver intended outcomes. Figure 3B demonstrates that DEECD does not know the exact funding arrangements for programs offered in Victorian government schools. As the majority of programs are funded from the schools budget, DEECD is unable to determine the demand, cost effectiveness or relative value of the programs.

Figure 3B

Program funding in 2012

|

Program |

Funding |

|---|---|

|

School-arranged settings |

Unknown |

|

Programs funded through Alternative Settings Fund |

There is inconsistent funding across regions, which is historically based. Most schools do not have access to this stream of funding |

|

Senior secondary re‑engagement programs |

Unknown |

|

School – Learn Local Partnerships |

Unknown |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

DEECD does not know if schools have the right resources and funding to meet their student cohort’s needs. Because DEECD does not routinely collect information about how much schools are currently spending on programs from their own budgets, it cannot assess the proportion of the Student Resource Package (SRP) required by schools to effectively meet student needs.

DEECD is currently collecting information on the programs receiving funding through the Alternative Settings Fund. It intends to use this data to inform work planned for 2012 and 2013 to investigate options to improve transparency, accountability, access and equity issues related to the Alternative Settings Fund. However, it has no intention to collect funding information on the other three program categories.

3.5.3 Number of students accessing programs

The uptake and coverage of programs is not adequately monitored by DEECD, nor is access and demand for programs. Without this information, DEECD cannot tailor programs to better target the right students and make sure that students are not being unfairly disadvantaged by school choices. Figure 3C shows that DEECD knows little about the number of students involved in the support programs and nothing about latent demand.

Figure 3C

Number of students in programs in 2012

|

|

Number of students involved |

Waiting lists |

|---|---|---|

|

School-arranged settings |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Programs funded through Alternative Settings Fund |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Senior secondary re‑engagement programs |

In 2011 there were 973 students across 69 schools. This data is incomplete. |

Unknown |

|

School – Learn Local partnerships |

Regional data shows 209 students were involved. However, 136 of these were between 15 and 19-years-old, even though these arrangements are intended to be limited to students under 15 years. |

Unknown |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

Although DEECD will be able to identify the number of students and student-days of attendance in programs funded through alternative settings from 2013, this updated data will not be able to identify which types of programs the students are attending.

3.5.4 Effectiveness of programs

Completion rates in Victoria have been relatively static since 2008. DEECD has not assessed whether support programs—which focus on assisting already disengaged students as well as students at risk of disengaging to remain engaged and complete Year 12 or equivalent—have been effective or efficient.

Schools visited as part of this audit stated that some programs are very valuable in engaging at-risk students, but this information is not captured or analysed centrally or regionally by DEECD on a regular or systematic basis.

If key measurements were tracked at regular intervals, schools and DEECD would be able to understand which factors most affect student outcomes. Not having measurable outcomes is a lost opportunity for effective continuous improvement across Victorian schools.

Although schools are advised to measure program and student outcomes internally, there are no consistent measures between schools. This means schools are unable to benchmark programs between like schools or cohorts of students, facilitating an objective standard by which schools and DEECD could measure program performance.

Without being able to analyse the effectiveness of programs which focus on assisting disengaged students and those at risk of disengaging, DEECD is unable to strategically address the needs of vulnerable students or assist schools to better identify and address their needs.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop a framework to oversee the provision of support to students at risk of disengaging, or who are disengaged from education, to assist them to complete Year 12 or equivalent

- analyse the impact of programs to determine which strategies have been effective, and why, in order to facilitate schools to use them more effectively

- improve data collection and analysis around how effective the department is in supporting schools to assist disengaged students and those at risk of disengaging to remain at school and complete Year 12 or equivalent.

4 The Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning

At a glance

Background

The Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) is an alternative senior secondary qualification with an applied learning focus. Students at risk of disengaging from education are more likely to undertake VCAL. Although it has not made an impact on overall retention or completion rates, VCAL has had a 60 per cent increase in government student numbers since 2006, and VCAL students rate it as an important factor in their decision to stay at school. In 2012, VCAL coordination funding was withdrawn from schools.

Conclusion

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) did not have sufficient evidence on which to base its recommendations to government to withdraw VCAL coordination funding. It failed to analyse or fully understand the role played by VCAL and its effect on the Victorian education system. Despite not being able to anticipate or advise what impact the changes would have, it recommended major changes to VCAL coordinator funding.

Findings

- DEECD does not collect and analyse the data it needs to fully understand the relationship between VCAL and student completion rates.

- DEECD did not use historical information to model the likely impact of VCAL funding changes.

- DEECD's advice to government on the impact of changes to VCAL funding ignored significant commissioned work.

Recommendations

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- develop fit-for-purpose outcome measures to recognise and manage risk in relation to Victoria's Year 12 and equivalent completion rates

- use sufficient evidence to analyse the impact of policy changes so that decision‑makers are comprehensively informed and advised.

4.1 Introduction

The Ministerial Review of Post Compulsory Education and Training Pathways in Victoria identified that a broader range of programs was required to meet the needs of young people in their post-compulsory years of education. Ultimately, this led to the launch of the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning in 2003.

Today, VCAL is an important part of the Victorian education system, providing students with an alternative pathway to complete Year 12 or equivalent. In 2010 about two-thirds of all VCAL enrolments (66.4 per cent) were in government schools.

VCAL is intended to provide students with the skills, knowledge and attitudes to enable them to make informed choices about pathways to work and further education. VCAL has three levels—Foundation, Intermediate and Senior. The three qualification levels cater for a range of students with different abilities.

Intermediate and Senior level VCAL are considered a Year 12 equivalent qualification. At the VCAL Intermediate and Senior levels, the learning program must include accredited Vocational Education and Training in Schools (VETiS) curriculum components.

VCAL is especially important for students at risk of disengaging, including those with low academic achievement and those from low socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds. These cohorts have disproportionally high VCAL enrolments. In 2011, 13 858 students enrolled in VCAL—an increase of 60 per cent since 2006.

Since the introduction of VCAL in 2003, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has provided coordination funding to schools offering VCAL. Funding for VCAL coordination was withdrawn in 2012.

This Part examines the role of VCAL in addressing completion rate issues and the basis on which recent funding decisions have been made.

4.2 Conclusion

While the decision to cease funding VCAL coordinators in schools will save the government $12.3 million per year, DEECD does not know how much it actually costs schools to deliver VCAL or whether schools can meet the demand for it. VETiS is a compulsory but costly component of VCAL, and any outstanding costs must be met by schools. DEECD does not know the current costs of providing VETiS, and is unable to determine if providing VETiS is sustainable at individual schools.

The information provided to decision-makers regarding the decision to cease the VCAL coordinator funding was incomplete and was not evidence-based. The limited critical information that DEECD possessed was not referred to in briefs and key stakeholders were not consulted. These actions raise broader concerns about DEECD's internal advice process strategies to improve student completion rates.

Increasingly, schools have to balance the benefits of running a full and comprehensive VCAL program against the rising cost of offering it.

The impact of any reduction in the availability or breadth of VCAL course offerings is most likely to impact on students from non-metropolitan or disadvantaged backgrounds. DEECD did not use adequate processes to anticipate the compounding impact of multiple changes affecting VCAL.

DEECD has informed schools that the 2012 funding arrangements for VETIS will continue in 2013. However DEECD is yet to finalise and announce any long-term funding arrangements for VETIS, making schools uncertain about the financial viability of providing VETIS in future years.

4.3 Funding changes that impact on the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning

Since the introduction of VCAL in 2003, DEECD provided funding to schools to coordinate all aspects of student administration in VCAL including program development, enrolment, assessment, monitoring and record keeping.

The funding was linked to the number of students who enrolled in VCAL and was capped at $125 218 per year per school in 2011. Since 2003, $95.1 million has been spent on VCAL coordination.

Despite VCAL coordination funding being capped, student enrolments have grown, on average, 9.78 per cent each year in government schools since 2006. This has created an increasing gap between available funding for schools in the coordination and delivery of VCAL, and the actual costs of coordination and delivery.

In August 2011, DEECD advised schools that the VCAL coordination funding was going to be withdrawn from January 2012, saving $12.3 million annually. Changes in the Vocational Education and Training sector may have further affected schools' capacity to deliver VCAL.

4.4 Advice provided for decision-making

DEECD has not adequately briefed decision-makers on changes to VCAL coordinator funding. It did not have a sufficient understanding of the cost to schools of offering VCAL, the factors driving its uptake, or of the variations in VCAL student outcomes by different cohorts.

Further, DEECD cannot accurately model the likely consequences of related policy changes, because it does not have sufficient data to understand, much less advise on, the disposition of the program.

4.4.1 Cost of providing the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning

DEECD has not examined VCAL running costs for schools and did not consult with schools to understand these costs prior to announcing the VCAL coordination funding changes.

VCAL is a mainstream senior school program. As such, its delivery is funded through the core component of the Student Resource Package (SRP). However, VCAL carries additional administrative and coordination costs compared to the main curriculum offering, the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE).

The decision to cease funding VCAL coordination in schools will save the government $12.3 million per year. To cover the gaps between core funding and the additional costs of coordinating and delivering VCAL, DEECD provided supplementary funding to schools using a base and per capita enrolment formula.

In 2005, DEECD received its commissioned report Review of the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning. Almost 70 per cent of schools surveyed for this report stated that having a dedicated VCAL coordinator was critical to the future success of VCAL. The report estimated that coordination represented about 15 per cent of the costs of offering VCAL. It recommended that resourcing for VCAL coordinators should continue as a targeted initiative within the SRP.

In 2011, DEECD commissioned a further report on VCAL Review of VCAL coordination funding in Victoria, VCAL funding models. This report found that many of the funding or resource pressures that schools experience are related to the delivery of VCAL, particularly for students with high needs.

The report confirmed the importance of the VCAL coordinator role and found that over half of VCAL coordinators thought funding levels were insufficient to deliver a VCAL program that met the needs of all their students.

Schools we visited that deliver VCAL confirmed that coordination is essential to providing a VCAL program that meets student requirements. These schools all stated that VCAL is more expensive to provide than VCE and, while indicative costings from audited schools varied considerably, they suggest that this is the case. Estimates varied from 27 per cent more to 595 per cent more. However, DEECD has not done any work to accurately determine the additional costs.

When briefing the government on funding changes to VCAL coordination, DEECD did not use any information from either the 2005 or 2011 reports. Nor did DEECD incorporate the report findings or refer to any of the recommendations made.

The brief to the Minister for Education providing information about the impact of the removal of VCAL coordination funding was also incomplete, referring only to high‑level analysis on special schools, which made up only 12.5 per cent of schools that offer VCAL.

Vocational Education and Training in Schools

VETiS is a compulsory element of Intermediate and Senior level VCAL. It costs more for schools to deliver vocational education than more traditional, classroom-based education. In recognition of this, DEECD provides additional funding to schools to cover the extra cost of delivering particular courses.

In 2011, DEECD increased the VETiS supplement by 1 per cent. The most recent detailed analysis that DEECD conducted was in 2009 and no further work has been undertaken to understand the costs to schools to provide VETiS. It is reasonable to assume that VETiS costs have risen in line with CPI, and that schools are covering this disparity in costs within existing funding arrangements.

In addition, the 2011 Review of VCAL coordination funding in Victoria, VCAL funding models report found that VETiS coordination is another major funding commitment for schools, particularly for structured workplace learning for VCAL students.

Changes to Vocational Education and Training sector

From 2013, all Vocational Education and Training (VET) providers will receive the same government funding for delivering the same subsidised course.

This removes the extra weighting in the subsidies that public providers (TAFEs) received for additional costs associated with staffing, student support services, libraries and teaching facilities. There have also been changes to the per-student-hour subsidies for courses included in the Victorian Training Guarantee.

The combined impact of both of these changes will change the VET market significantly. Some training providers have indicated that courses will be cancelled and the schools’ VETiS contributions will increase. This will inevitably increase the costs to schools of offering VCAL and will reduce the availability of certain course options.

4.4.2 Student demand

DEECD does not know why students choose VCAL and has not analysed variations in its uptake between regions or student cohorts. This means it does not know if changes to VCAL provision will disproportionately affect a particular group of students. Therefore DEECD cannot target additional support to manage the impact on them.

VCAL enrolments are the only indicator of demand that DEECD collects. However, this is not an accurate metric, as supply of VCAL places at the local level will affect the number of students that can enrol.

In 2011, government school VCAL enrolments were 13 858, an increase of 60 per cent since 2006, and nearly 70 per cent of government schools offered VCAL.

The importance of VCAL in retaining students in education can be strongly inferred from the contents of DEECD surveys of school leavers. In 2010, 87 per cent of VCAL students said VCAL being offered was an important factor in their decision to stay at school.

While DEECD does not believe that there is unmet demand for VCAL, half of the audited schools said they restrict the number of VCAL places offered. Staff in DEECD’s regional offices stated they were aware of some schools capping student numbers.

4.4.3 Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning students

Though not an explicit objective of VCAL to engage students at risk of leaving school, students from some cohorts who are associated with lower completion and retention rates are more likely to undertake VCAL.

Two of the most easily measured and identifiable risk factors for disengagement from education are SES and educational achievement, which both have disproportionately high VCAL enrolments.

While the profile of these two at-risk cohorts clearly demonstrates a correlation with the uptake of VCAL, DEECD has not analysed why VCAL is a pathway of choice for them.

Without a clear understanding of the push and pull factors for vulnerable students and their choices to remain studying at school, DEECD is unable to address their needs.

Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds

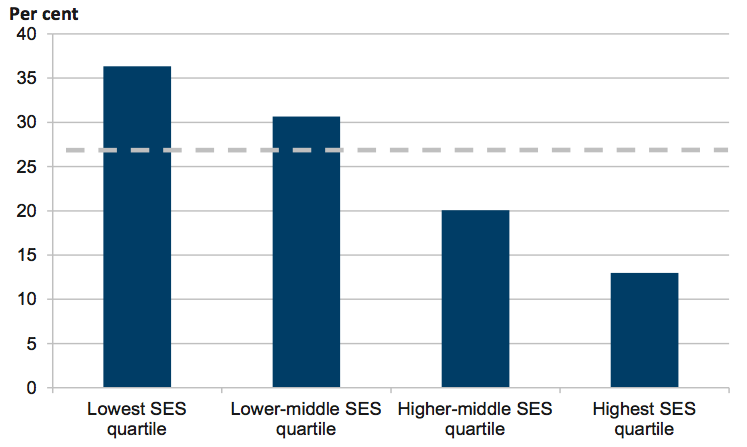

Students who enrol in VCAL are over-represented in the two lower SES quartiles.

Low SES equates to greater disadvantage and is an acknowledged risk factor for disengaging from educational studies. Figure 4A shows that students from lower SES backgrounds are more likely to do VCAL.

Figure 4A

Distribution of Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning students' socio-economic status

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of 2011 Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

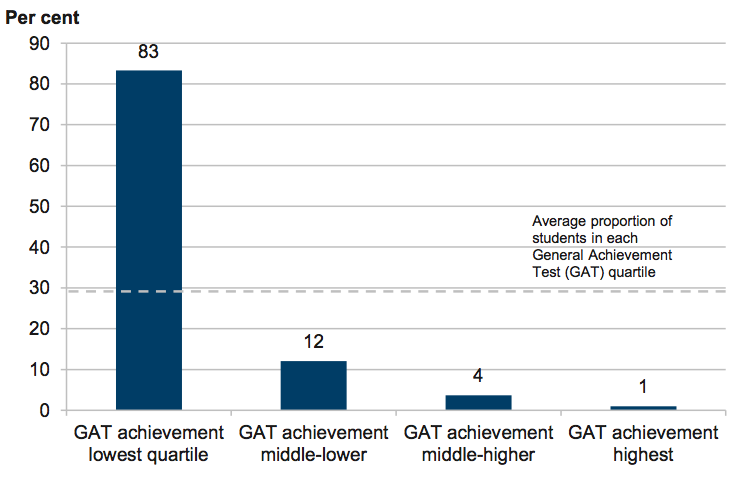

Students with lower achievement

Low academic achievement is also a known risk factor for student disengagement. The General Achievement Test (GAT) is a test of general knowledge and other skills taken by all Victorian students prior to completing their VCE.

Only 4 per cent of VCAL students undertook the GAT in 2011, as it is only compulsory for all students (VCE or VCAL) who are enrolled in any VCE Units 3 and 4 with scored assessment. Figure 4B shows that in 2011 over 83 per cent of VCAL students who sat the GAT scored in the bottom quartile. By comparison, only 18.5 per cent of students who completed VCE scored in the bottom quartile of the GAT.

Figure 4B

Distribution of Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning students' performance on the General Achievement Test

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of 2011 Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data