Unconventional Gas: Managing Risks and Impacts

Overview

Unconventional gas is a collective term for three natural gas sources found within different rock layers in the earth’s crust, known as coal seam, tight and shale gas. Between 2000 and 2012 there was some exploration for unconventional gas but no commercial discoveries. In 2012, the government placed a moratorium on coal seam gas exploration—later expanded to all onshore gas.

This audit examined whether Victoria is well placed to effectively respond to the potential environmental and community risks and impacts of onshore unconventional gas activities in the event that these proceed in this state.

Victoria is not as well placed as it could be to respond to the risks and impacts that could arise if the moratorium is lifted, allowing unconventional gas activities to proceed. The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) did not sufficiently assess the risks or effective regulation of these activities prior to 2012, although it has made progress on this since then.

The infancy of the industry and the moratorium provide an ideal opportunity for the government to evaluate the full range of potential risks and impacts of unconventional gas. There is key work that DEDJTR needs to do to inform the government about risks, before the moratorium is reviewed. It will also need to better regulate unconventional gas development, should the government allow it to proceed, supported where necessary by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. DEDJTR can also improve its earth resources regulation more generally.

Unconventional Gas: Managing Risks and Impacts: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2015

PP No 76, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Unconventional Gas: Managing Risks and Impacts.

The audit examined whether Victoria is well placed to effectively respond to the potential environmental and community risks and impacts of onshore unconventional gas activities in the event that these proceed in this state.

I concluded that Victoria is not as well placed as it could be to respond to the risks and impacts that could arise if the moratorium is lifted allowing unconventional gas activities to proceed in this state. I found that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) did not sufficiently assess the risks or regulation of these activities prior to 2012, although it has made progress in this since then.

The infancy of the industry and the moratorium provide an ideal opportunity for the government to evaluate the full range of potential issues, risks and impacts of unconventional gas. There is key work that DEDJTR needs to do to inform the government about risks and improve the regulatory system in general. It will also need to better regulate unconventional gas development, should the government allow it to proceed. The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning will need to support the water and planning aspects of this work.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

19 August 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Leader Maree Bethel—Team Leader Catherine Sandercock—Analyst Katrina Castles—Analyst Christina Bagot—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Kris Waring |

We do not yet know the extent and commercial feasibility of Victoria's unconventional gas resources. The economic and energy supply reasons for developing an unconventional gas industry here are not clear either.

There is an ongoing dialogue in the community about our energy resources and sustainable development. Sustainability is not just about ensuring continued supply of essential resources or economic benefits. Environmental and social values are integral to this conversation, although often harder to quantify, but essential if we are to avoid a damaging legacy in years to come.

What we do know is that there are significant challenges in developing a sustainable unconventional gas industry. These include potential social and land-use impacts and conflicts resulting from Victoria's relatively small land mass, dense population, scarce water resources and high reliance on agriculture, as well as the need to respond to climate change.

Substantial national and international studies have comprehensively identified the potential and known risks unconventional gas poses to the environment and the community. The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) has not identified the full range of risks, nor comprehensively assessed the likelihood and consequences of these risks in Victoria, should an unconventional gas industry develop. Since 2014 it has made good progress in identifying and assessing the key risks to water resources, in partnership with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), and in identifying community concerns.

Information on risks is needed to properly inform decisions about the economic, environmental and social sustainability of any future unconventional gas industry.

There are major problems with applying the current regime for regulating earth resources to unconventional gas activities, which DEDJTR has used to regulate those activities to date. DEDJTR's response to regulating unconventional gas has been largely reactive, particularly before 2012, and characterised by the absence of many ingredients essential for better practice regulation.

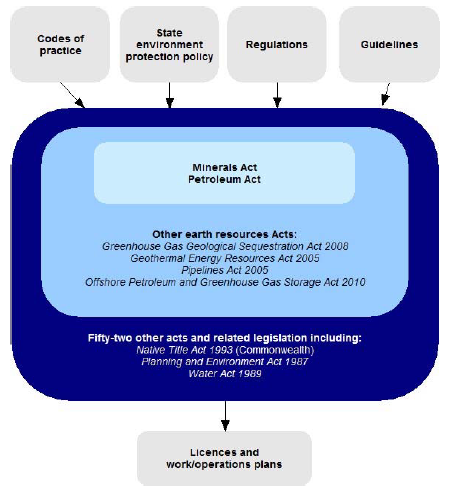

As a result, the regime has too few environmental controls, weak consideration of the competing interests for the land involved and potential social impacts, a lack of early community engagement and too much ministerial discretion. The profusion and complexity of the regulatory system—which spans 58 Acts plus a host of regulations, codes of practice, guidelines and the like—severely compromise its transparency, clarity, efficiency and effectiveness.

Crucially, there are also no existing land-use planning or impact assessment mechanisms that adequately consider social, environmental and economic values and impacts when determining if, where and when unconventional gas activities should occur—and before licences are granted.

The intent of this audit is to apprise policy makers so they can make decisions that balance economic benefits with environmental and social impacts, and give due regard to the strengths and weaknesses of our current regulatory regime. It presents objective findings and recommendations to inform the final decision of government so that it can be made in the best interests of the Victorian community rather than individual stakeholders.

I have today written to the Honourable David Davis MP, Chair of the Parliamentary Inquiry into Unconventional Gas in Victoria, informing him that I have tabled my report. I am pleased that the committee's terms of reference will have regard to my report. My recommendations are based on extensive and rigorous information collection and analysis and I believe the committee would be well served to use them to inform both its deliberations and its final report. I look forward to discussing the report, its findings and recommendations with the committee

I would like to thank the staff of DEDJTR and DELWP for their assistance and cooperation throughout this audit.

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

August 2015

Audit summary

Unconventional gas refers to a source of natural gas found in different rock layers in the earth's crust. It is more difficult to extract than conventional gas and requires different combinations of techniques such as drilling and hydraulic fracturing or 'fracking'. The three types of unconventional gas are coal seam gas (CSG), tight gas and shale gas. In Victoria CSG is regulated under the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 (Minerals Act), and tight and shale gas are regulated under Petroleum Act 1998 (Petroleum Act).

In 2012, a government moratorium put CSG exploration and development on hold in Victoria, ahead of national reforms for regulating CSG and the outcomes of scientific studies and community consultation. Until then there was only a fledgling unconventional gas industry as no commercial unconventional gas reserves had been found.

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) administers the Minerals Act and the Petroleum Act for the Minister for Energy and Resources. The objectives of these acts include minimising any adverse environmental and community impacts. The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Environment (DELWP) also has responsibilities for managing unconventional gas, linked to water resource and crown land management and land-use planning.

This audit examined whether Victoria is well placed to effectively respond to the potential environmental and community risks and impacts of onshore unconventional gas activities in the event that these proceed in this state.

We reviewed the activities and approaches DEDJTR and DELWP have used since 2000 to understand and manage these risks and impacts. We also reviewed national and international literature and spoke to experts in the field to ascertain the current knowledge about these matters and to identify better practice.

Conclusions

Victoria is not as well placed as it could be to respond to the environmental and community risks and impacts that could arise if the moratorium is lifted allowing unconventional gas activities to proceed in this state. DEDJTR did little to assess the risks and or plan how it could strengthen the regulation of these activities prior to 2012, despite growing public concerns about the potential risks. DEDJTR initially assumed that exploration for unconventional gas could be managed using the existing regulatory framework with minor amendments and therefore only minimal changes to licence conditions, regulations, codes and guidance materials were warranted.

DEDJTR has made progress since 2012 to better understand the risks to water resources, the community concerns and the strengths and weaknesses of the current regulatory system, but there are still gaps in its approach.

Experience here, and in other jurisdictions indicates that even if a commercial discovery was made soon after the moratorium was lifted, it would take at least five years to reach commercial production. The infancy of the industry and the current moratorium provide an ideal opportunity for the government to evaluate the full range of issues, risks and impacts of unconventional gas. This puts the state in a fortunate position of having time to more fully comprehend the risks and impacts of this new industry in Victoria. This will enable the government to adjust its policy and regulatory settings as necessary. There is time, should government decide to allow unconventional gas activities to proceed, to:

- improve our scientific knowledge of both the above and below ground characteristics of prospective sites and the potential and known risks to water, air, and land

- improve our consideration and assessment of the social impacts of this industry

- reform the current planning and regulatory systems to enable them to better deal with the region-wide and cumulative social and environmental impacts of this industry

- address deficiencies in community engagement, the transparency of decision-making and the oversight of the industry's environmental performance.

Unconventional gas exploration to date

The extent, location and commercial feasibility of unconventional gas resources in Victoria is not completely unknown, but is untested. In Victoria the responsibility for locating and testing gas resources currently lies with the industry.

Victoria has a relatively small land mass, a high population and heavy economic dependence upon the agricultural sector in regional areas. There is also a high level of concern about unconventional gas impacts in some sectors of the community. Coupled with the proximity of large gas fields offshore, the cost of commercial production, fluctuating energy markets, the need to deal with climate change issues and the growth of renewable energy sources, there are significant challenges to the development of an unconventional gas industry in Victoria.

Interest in the possibility of unconventional gas in Victoria started in the early 2000s. Between 2000 and 2014, at least 100 licences allowed unconventional gas activities. This has provided some information about potential resources, but commercially viable discoveries have yet to been made. In other states and territories, such as Queensland, CSG has been in commercial production since 1996 and is now supplying both domestic and international markets.

In August 2012, the previous Victorian government introduced a moratorium on new onshore CSG exploration licences and all hydraulic fracturing activities. The government wanted to participate in the development of new standards for regulating CSG being driven by the Commonwealth and other states, to better understand the implications for Victoria. The moratorium was expanded in late 2013 to include all onshore gas exploration while water resource studies and focused community consultation were being undertaken. In January 2015 the current government announced a Parliamentary Inquiry into unconventional gas with a final report planned to be presented by December 2015.

Findings

Following the emergence of an unconventional gas industry in Victoria in the early 2000s, the government through its relevant agencies—currently DEDJTR—focused its attention on encouraging industry development. It did not adequately consider or assess the risks associated with unconventional gas exploration and production.

The scientific literature is clear that the development of different sources of unconventional gas poses a range of risks, both above and below ground. These relate to water and the environment, and community health and amenity. Potential impacts include:

- competition for groundwater

- groundwater, soil and air contamination

- habitat fragmentation

- impacts on landscape values

- noise and dust

- impacts on human health.

Scientific literature and reviews have concluded that risks can be managed if there is:

- comprehensive baseline data and monitoring

- appropriate siting based on sustainability principles

- implementation of best practice construction and operation standards, including well design and management

- implementation of best practice risk mitigation controls

- a strong regulatory framework

- early and risk based community engagement.

No jurisdiction has adequately addressed all these principles to date.

Understanding unconventional gas risks

DEDJTR has not comprehensively assessed the likelihood and consequences of the risks associated with unconventional gas activities in Victoria. As a result, there are significant gaps in scientific information that need to be filled to understand the likelihood, scale and consequences of the risks associated with this industry.

This is because DEDJTR regarded unconventional gas as an industry that could be managed using the existing regulatory system in the decade following the industry's emergence in the early 2000s. DEDJTR considered commercial production of coal, gold and mineral sands required a higher priority risk management focus based on the limited number and type of unconventional gas exploration activities underway. In contrast, as unconventional gas had not progressed to commercial production it assumed that the existing regulatory system would suffice. This was despite having identified, from around 2000, that as a new and growing industry CSG exploration needed new regulatory approaches. Consequently, DEDJTR's identification of risks over this period was slow, informal and ad hoc.

From 2010 the risks and impacts other jurisdictions were having to deal with became clearer to DEDJTR. There was also increasingly vocal community concern about impacts of an unconventional gas industry given the experiences in Queensland with CSG. DEDJTR was slow to engage with the community on these issues.

DEDJTR's approach to identifying and assessing risks improved from 2012. This was driven by Victoria's commitment to Commonwealth initiatives on CSG, as well as the government's focus on understanding community concerns and identifying water resource risks.

Based on what is known to date, the areas most likely to contain an unconventional gas resource are the Gippsland and Otway basins. If this is the case, as well as potentially providing new opportunities, any new industry may come into conflict with other land uses, particularly as these basins contain highly productive agricultural land. Greater possibilities appear to exist for tight and shale gas than CSG, which would make some of the risks and considerations, and even the footprint on the landscape, different from the experiences in Queensland and New South Wales. Without better information and scientific knowledge about these basins, government is limited in its ability to make informed decisions about the feasibility and sustainability of an unconventional gas industry in Victoria.

Reforms are needed to address the distinct challenges associated with developing unconventional gas resources. Key challenges include managing:

- the potential impact of these activities over large areas both above and below ground

- the cumulative impacts over time and those associated with a greater concentration of infrastructure

- the coexistence and conflict with existing and potential other resource uses such as agriculture, tourism and urban development.

Regulating unconventional gas activities

The current regulatory system will not be able to effectively manage unconventional gas risks. The system is complex and fragmented, making it difficult for DEDJTR to effectively implement and administer. This also creates difficulties for licensees as they navigate their way through the system. To complicate things further, DEDJTR, DELWP and other regulators responsible for administering the system have overlapping roles and responsibilities. Together these issues severely impact on the system's transparency, clarity and efficiency.

Victoria's regulatory system does not currently contain clear and transparent requirements for the mandatory risk-based impact assessment of unconventional gas activities. There are referral triggers for CSG applications under both the Environment Effects Act 1978 (EE Act) and the Commonwealth's Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, but these are outlined in non-binding guidelines. There are no similar triggers for tight and shale gas. The decision as to whether an environmental impact assessment is required under the EE Act is at the discretion of the Minister for Planning. Guidelines informing this discretion should be reframed to clarify and consolidate the decision criteria currently split between the 2012 amendment to the Ministerial Guidelines and the Victorian Protocol under the National Partnership Agreement on Coal Seam Gas and Large Coal Mining Development.

The Minerals Act allows for an impact assessment to be required prior to commercial production but only at the Minister for Energy and Resources' discretion. This provision has never been used. The Petroleum Act has more general environmental assessment provisions for all stages of resource development, however, these are also at the Minister for Energy and Resources' discretion.

Other jurisdictions and industries have described the technical and operational best practices needed to effectively manage the scale of risks posed by unconventional gas activities. This is done through a range of codes of practice that provide industry with certainty about what it needs to do to manage risks, and the public with an understanding of how the risks will be managed. These jurisdictions also require approved technical experts to independently review and oversee key elements of the regulatory system.

Victoria does not have a comprehensive code of practice or set of codes to manage the range and scale of risks posed by unconventional gas activities. Nor does the regulatory system require an independent review of how risks are assessed, managed and monitored as is the case with other activities in Victoria, such as landfills and contaminated sites.

We identified weaknesses in DEDJTR's approach to administering the system, particularly with its work plan approval and compliance activities. Its licences and work plan approvals do not sufficiently address risks or monitoring requirements. Its compliance activities are poorly informed and planned, and not always executed effectively. There were examples where—despite identifying poor licensee practices—action was not taken to review or change its approach, or to reconsider whether existing controls were adequate.

DEDJTR has started work to address some of these issues. It has assessed the regulatory system against the Commonwealth's standards for CSG and benchmarked its performance as a regulator against other jurisdictions. DEDJTR will need to develop a much more reflective, adaptive and systematic approach to its activities to achieve better practice in unconventional gas regulation and management and to effectively minimise environmental risks.

The way forward

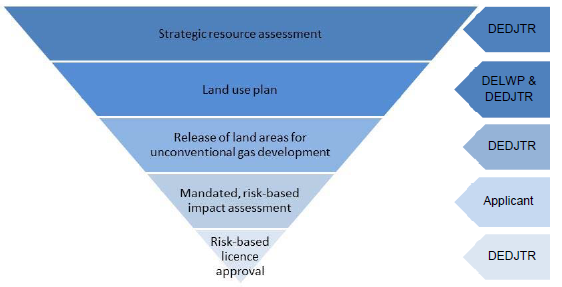

Our review of the Victorian regulatory system, past unconventional gas activities and literature on managing unconventional gas, has identified key steps needed to provide a sustainable foundation for an unconventional gas industry, should this activity be allowed to proceed. These steps should provide greater certainty and security for industry and improve community participation and understanding of these activities and of the basis for government decisions.

Natural resources need to be managed sustainably. Competing interests need to be assessed equitably based on reliable data and an understanding of the environmental, social and economic risks, and benefits of each resource to both the local community and the state as a whole.

The starting point is to improve the way earth resources—which have been pre-competitively identified at a regional scale—are identified and assessed as an appropriate land and resource use in terms of sustainability. DEDJTR firstly needs to improve its identification of areas that offer the highest potential for the occurrence of unconventional gas through an improved resource assessment process. Once a region has been identified as potentially containing unconventional gas through such an assessment, DELWP should facilitate the development of a land-use plan for any area before it is approved for unconventional gas development. Land-use plans are useful tools to define where certain uses and/or activities can take place sustainably and to determine their impacts on the landscape. Their purpose is to select land uses that will best meet the needs of the Victorian community while safeguarding natural resources for the future.

Currently decisions about approving areas for development are made without a comprehensive resource assessment and land-use planning exercise.

For areas identified as sustainable, DEDJTR should develop guidelines in coordination with DELWP and other natural resource managers that identify the key landscape, environmental and social factors and considerations that need to be taken into account and assessed as part of any proposal to develop an earth resource in that area. This can be done using existing land, natural resource and water and groundwater information held by DELWP and the information that will be generated from the Victorian water studies and the Commonwealth's bioregional assessments.

DEDJTR would then be able to provide prospective licensees with improved information around the potential for unconventional gas in an area and the key economic, environmental and social considerations that would form part of an assessment and approval process.

This detail should form a part of the information package accompanying areas released for exploration. This will improve the transparency around the key issues and risks and the level of impact assessment required for specific areas. Currently this is only done for petroleum exploration areas, and with only limited information about the potential resource. It does not include economic, environmental and social considerations. The type and level of a mandated, risk-based impact assessment should be tailored around these guidelines.

A further, critical part of the reform process is improving landowner and community participation. Communities need to be engaged early and the level and type of engagement through the life cycle of a proposal should be tailored to the risk. Communities should be able to contribute to and influence decision-making in relation to the identification of sustainable earth resource development areas. Once determined, community consultation and engagement should be focused on information sharing in relation to how risks are to be managed and the performance of a company over the tenure of an operation.

The current access and compensation arrangements for landowners are often criticised for not being fair or just. There is an imbalance between the bargaining positions of landowners and industry, and the legislation unfairly limits possible compensation to those directly affected.

Existing community involvement is largely determined by whether activities are conducted under an exploration or commercial production licence and does not reflect the degree of risk to the community created by these activities. Options such as the Royalties for Regions schemes that operate in Western Australia and Queensland should be considered for Victoria. These strategies recognise the value of compensating local communities who may be impacted by an unconventional gas industry by redistributing some of profits back into the community.

Community and regulator confidence can also be improved through the independent oversight of the industry's environmental performance and improved transparency in decision-making and performance reporting.

The recommendations in this report focus specifically on informing the management of future unconventional gas activities should the moratorium be lifted and the government decide to support that industry. However, many of them also have broader application. For example, they may also benefit the management of onshore conventional gas activities as well as other earth resources activities more generally. For this reason, we also ask DEDJTR to consider the benefits of applying these recommendations to its earth resources responsibilities more broadly.

Recommendations

To inform the government's review of the moratorium and subsequent decision about whether or not an unconventional gas industry should proceed in Victoria, that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources, in partnership with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- develops a risk-based strategy which:

- identifies known and potential risks to water, air, land and the community associated with the development of an unconventional gas resource, using available information and data and the input of relevant agencies as needed

- prioritises the actions that would need to be taken for an unconventional gas industry to proceed and identifies roles and responsibilities for these.

Should the moratorium be lifted and unconventional gas exploration and development be allowed to proceed, that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- coordinates an interdisciplinary process with representatives from government departments, scientific organisations and industry to:

- identify the baseline data needed—geological, hydrological, environmental and social—to be collected through regional studies at a level of resolution and accuracy that will enable future risks and potential impacts to be clearly identified and assessed

- identify opportunities to fund this work.

- progresses reforms of Victoria's regulatory system to underpin sustainable unconventional gas activities, specifically focusing on:

- fully implementing the National Harmonised Regulatory Framework for Natural Gas from Coal Seams' 18 leading practices for coal seam gas, and for other types of unconventional gas, where relevant and appropriate

- reviewing the licence conditions and requirements of work and operations plans to align with the leading practices in the National Harmonised Regulatory Framework for Natural Gas from Coal Seams and any other better practices identified through regulatory reform

- working with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, to address the gaps, inadequacies and unclear roles and responsibilities within the regulatory system, to better manage the impacts and challenges related to water resources

- information disclosure

- well integrity

- hydraulic fracturing activities

- produced water

- fugitive emissions

- well decommissioning and rehabilitation obligations

- baseline and ongoing monitoring

- performance assurance

Should the moratorium be lifted and unconventional gas exploration and development be allowed to proceed, that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, in consultation with the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- develops a land-use plan to determine the sustainability of an area for the extraction of unconventional gas prior to any licence being issued

- reviews models to implement a mandated impact assessment process under the Environment Effects Act 1978 and the relevant earth resources Act/s.

To improve the regulation of all earth resources, regardless of whether or not the moratorium is lifted and unconventional gas exploration and development allowed to proceed, that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- strengthens and clarifies the regulatory system to better manage all earth resources, giving consideration to:

- consolidating the earth resources Acts into a new single, integrated earth resources management Act that is risk based and addresses environmental, economic and social priorities in decision-making

- securing qualified, objective and independent environmental regulation capability and oversight for the licensing and environmental performance of earth resource industries through reviewing models from other jurisdictions

- implementing a mandatory risk-based environmental impact assessment process

- developing an approvals system that is risk based in proportion to the activities proposed, using risk-based work plans as one of the elements

- requiring risk-based environmental management plans for all stages, from exploration to decommissioning and aftercare

- requiring licensees to seek third party oversight and auditing for key elements of their environmental performance

- identify and monitor emerging issues

- consistently and comprehensively assess licences, work and operations plans

- consider the available evidence and clearly document the rationale of decisions.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix D.

1 Background

1.1 What is unconventional gas?

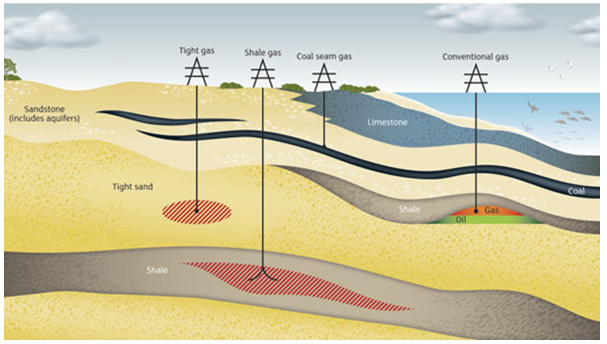

Unconventional gas refers to an underground source of natural gas found in certain rock layers. Natural gas is primarily composed of methane and is used as an energy source. There are four types of rock structures that can be sources of natural gas; 'conventional' rock sources and three 'unconventional' sources—coal seams, tight rocks and shale rocks. The different sources of gas and their relative depths are shown in Figure 1A. Conventional and unconventional sources can be co-located within rock structures.

Figure 1A

The location of unconventional gas types in the earth's layers.

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

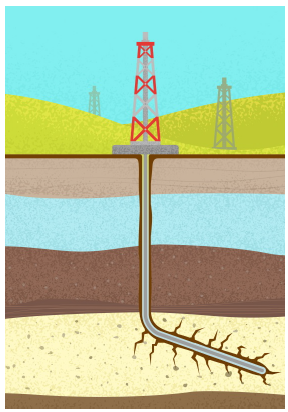

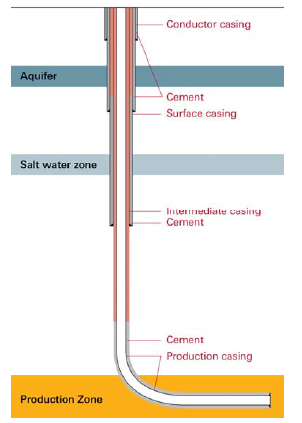

Conventional gas is generally easier to access and extract than unconventional gas. With the former a well is drilled directly into gas trapped within porous rocks. Once tapped the gas flows readily. Coal seam gas (CSG) is trapped within the gaps and cracks of the coal seam by water pressure, so water must be extracted for the gas to be released. Shale and tight gas are located in the pores of dense rock and these rocks almost always need to be fractured to release the gas. This is usually done by hydraulic fracturing, which involves pumping water, chemicals and sand into a gas well under high pressure to fracture the rock and release the gas.

The commercial production of unconventional gas has historically been uneconomical due to the difficulties in extraction. Advances in horizontal drilling technology since the late 1980s have increased access to areas where unconventional deposits are located. This drilling method, combined with hydraulic fracturing, has increased the productivity of unconventional wells. Along with oil and gas pricing trends, these factors have enabled commercial production to emerge around the world.

1.2 Context for the development of unconventional gas in Victoria

In Victoria, there has been exploration for both onshore coal seam and tight gas but no production, and onshore natural gas has only been produced commercially from conventional sources.

The likelihood that unconventional gas could be commercially extracted in Victoria and be competitive with the other states is still untested. In particular, there is uncertainty about the potential for Victoria's large coal deposits to produce CSG. These deposits are brown coal, which is shallower, softer and has lower gas content than the black coal deposits that are producing CSG in Queensland and New South Wales (NSW). CSG has not yet been produced commercially from brown coal anywhere in the world.

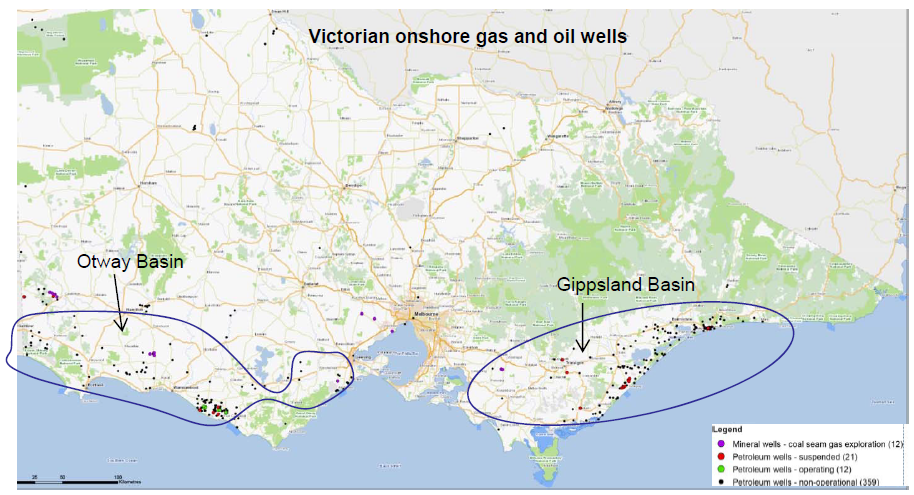

The exact location and extent of Victoria's unconventional gas resources is untested. Onshore exploration has identified that the Gippsland and Otway basins have the largest potential onshore unconventional gas reserves, as seen in the following map.

Notes: The mineral wells do not include commercially sensitive sites.

The operating wells either produce co2 or store natural gas as part

of the eastern Australian gas supply.

The non-operational wells date back as

early as the 1920s and include oil wells.

Conventional onshore gas exploration in Victoria dates back to the 1950s. Although unconventional gas exploration was first contemplated in the 1980s it took until the early 2000s before exploration began. Since then it has been limited in both geographical spread and the range of exploratory activities conducted.

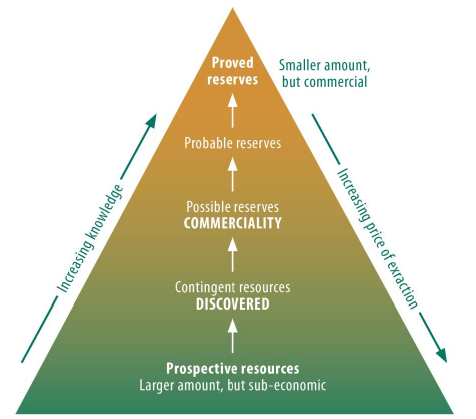

The Society of Petroleum Engineers identifies three classes of petroleum resources according to their potential for commercial production. Prospective resources have a large uncertainty about them. Once gas has been discovered the resource is described as contingent and only proved reserves are considered ready for commercial production, as shown in Figure 1B. Victoria's resource status has not progressed beyond the contingent stage.

Figure 1B

Stages of discovery for petroleum resources

Source: Australian Council of Learned Academies, Engineering energy: unconventional gas production: a study of shale gas in Australia, final report 2013.

The need and desire for an unconventional gas industry in Victoria are likely to be influenced by a range of factors, including:

- the cost of producing the resource

- domestic and international energy demand and pricing

- climate change and the growth of renewable energy sources

- economic development in regional areas

- compatibility with sustainable natural resource use and existing land uses

- community attitudes.

1.2.1 Global and domestic energy needs and production

Global energy demands are increasing. The International Energy Agency's 2014 Energy Supply Security: The emergency response of IEA countries report indicated that natural gas is increasingly important in the global energy mix, growing from 16 per cent to over 21 per cent of total primary energy supply since 1974 and still rising at over 2 per cent a year.

Globally, natural gas is regarded as a superior source of electricity for a number of reasons. Technically and financially, it is a lower-risk resource and gas plants can be constructed quickly relative to other energy facilities.

A growing population, combined with increased energy demands and climate change imperatives, have contributed to the surge in interest for new sources of natural gas worldwide, and in unconventional gas as the main untapped resource. Within an increasingly carbon-focused global economy—where greenhouse gas emissions generate costs—natural gas has been characterised as a transition resource towards reliance on renewable energy sources. This is because it produces less greenhouse gas emissions when burnt than coal and oil.

Australian gas production

Victoria, NSW, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania are all connected by gas pipelines and form the eastern Australian gas market.

The eastern gas market has traditionally provided gas for domestic use only. The development of liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities in Queensland is changing this. Many industry assessments predict that gas exports from Queensland will increase the domestic gas price in the eastern market from the current relatively low price to reach parity with increasing international prices.

Several industry reviews and the Australian Government's 2015 Energy White Paper argue that one of the best ways to tackle rising gas prices will be to increase the supply of gas by promoting onshore unconventional gas production.

CSG has been commercially produced in Queensland since 1996 and in NSW since 2001 but the development of shale and tight gas resources is still in its infancy. Minor shale gas production commenced in South Australia in 2012 but tight gas is yet to be commercially produced in Australia.

The vast majority of CSG is being produced in Queensland, with a small amount produced in NSW. The Productivity Commission's 2015 report on Examining Barriers to More Efficient Gas Markets identified that the proven and probable gas resources in the Surat Basin and Bowen Basin in Queensland have grown roughly tenfold since the 1980s. Figure 1C shows that Western Australia, the Northern Territory and South Australia all have larger probable resources, but the commercial potential of these has not been proven, while Victoria and Tasmania have far less unconventional gas potential.

Figure 1C

State comparison of onshore unconventional gas potential(a) and drilling activity (number of wells), 2013

State or territory |

Production |

Proved reserves |

Contingent resources |

Prospective resources |

Wells drilled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Queensland |

264 |

41 124 |

Not available |

164 000 |

1 000 |

NSW |

3 |

284–3 919 |

527–3 757 |

14 401 |

10 |

Western Australia |

none |

none |

3 275 to 5 898 |

427 000 |

15(b) |

South Australia |

none |

none |

1 725 to 6 807 |

45 000 to 268 000 |

13 |

Northern Territory |

none |

none |

none |

257 276 |

10 |

Victoria |

none |

none |

403–1 212 |

452 |

none |

Tasmania |

none |

none |

none |

none |

none |

(a) Gas

potential specified in peta joules.

(b) Data

were not available for 2013 alone for Western Australia—the 15 wells were drilled between 2005

and 2013.

Note: Where

available, the range in the estimates of resources/reserves has been included.

Source:

Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Upstream Petroleum and Resources

Working Group Report to the Council of Australian Governments' Energy Council, Unconventional

Reserves, Resources, Production, Forecasts and Drilling Rates,2014.

Most gas extracted in Victoria to date has come from conventional gas fields in Bass Strait where over 80 per cent of Victoria's offshore gas reserves are located. The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) has calculated that production from the offshore gas fields in Victoria is worth approximately $1.5 billion annually.

1.2.2 Status of the industry in Victoria

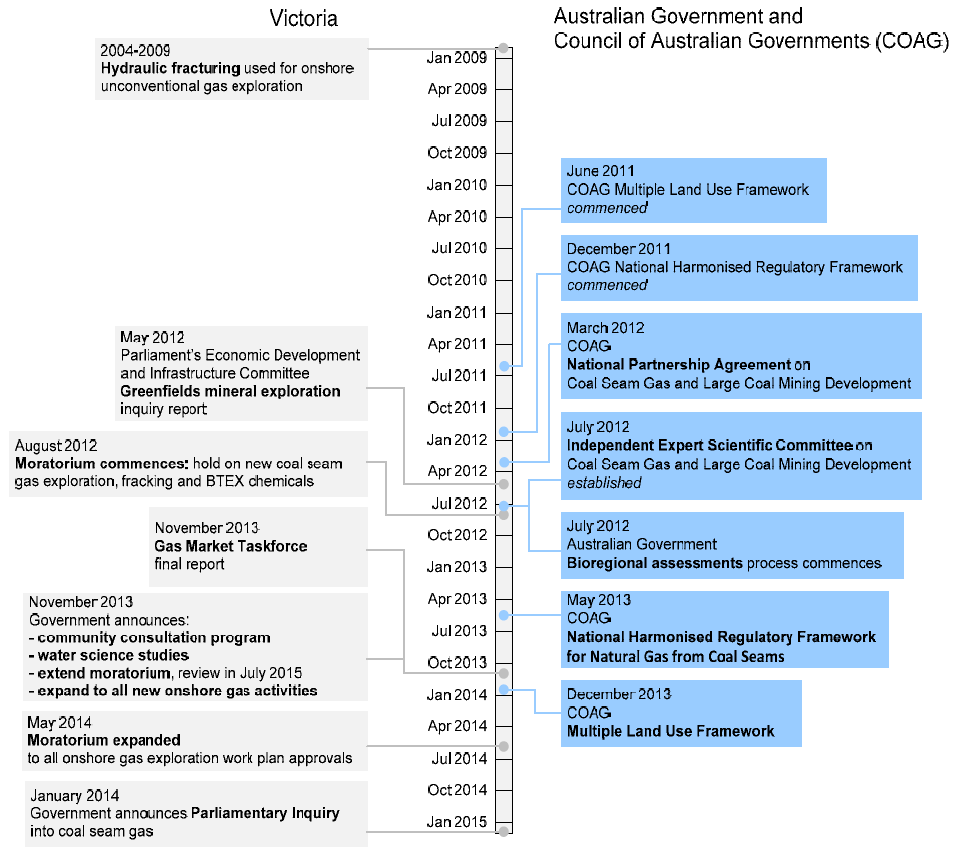

The onshore unconventional gas industry in Victoria has not progressed significantly. This is largely because of the size and proximity of the offshore reserves in Bass Strait and off the coast at the west of the state, and uncertainty about how much onshore gas Victoria has compared to the known reserves in Queensland and NSW. The previous government also put a moratorium on new onshore CSG exploration in 2012, which the industry considered to be a disincentive to investment in onshore gas exploration. Appendix A presents a time line of unconventional gas events in Victoria and nationally since 2009.

Between 2000 and 2014, at least 100 licences were active that allowed unconventional gas exploration or production:

- CSG—the 60 licences that allowed CSG exploration were granted between 2000 and 2012, including 33 for the Gippsland Basin and 17 for the Otway Basin.

- Tight and shale gas—the 40 licences that allowed tight and shale gas exploration were granted between 1999 and 2013, including nine for the Gippsland Basin and 29 for the Otway Basin.

At least 73 wells were drilled on around 26 licences, although some of these targeted conventional gas. Figure 1D summarises these activities and illustrates the industry's slow development.

Figure 1D

Summary of unconventional gas exploration in Victoria

Exploration for CSG and tight gas has occurred in both the Gippsland and Otway basins. Since 2000, only one unconventional gas exploration licence has confirmed the discovery of a potential gas reserve and progressed to the next exploration stage, which is called retention. This was for tight gas, near Seaspray in the Gippsland Basin. Key events over this period were:

The CSG wells were drilled and fracked at depths between 600 and 1 500 metres. CSG wells were fracked 12 times between 2007 and 2008. The tight gas wells were drilled to depths between 1 000 and 3 600 metres, with hydraulic fracturing at around 2 500 metres. There were 11 hydraulic fracturing operations in tight gas wells between 2004 and 2009. The groundwater aquifers that currently provide water to farmers, industry and towns in the Gippsland Basin near Sale extend from close to the surface to around 1 300 metres below. This means the coal seams in the basin are located within the deeper aquifers, and the tight and shale gas rocks sit below the aquifers. In the Otway Basin near Warrnambool the aquifers occur from close to the surface to around 900 metres below and are largely above the coal seams in the basin, and above the tight and shale gas rock layers. While some licensed exploration areas are very large, the total size of the drilled sites on any licence to date has been significantly smaller. For example, the onshore Gippsland Basin is 7 700 square kilometres and hosts the largest unconventional gas licence, at 3 800 square kilometres. In comparison, drilling activities have occupied less than 3 square kilometres of the licensed area. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.3 The Victorian moratorium

In August 2012, the previous Victorian Government introduced a moratorium that placed a hold on approving new onshore CSG exploration licences and all hydraulic fracturing activities. This was done to halt activities while the government awaited the development of a regulatory framework for CSG by the states and Commonwealth. It followed the signing of the National Partnership Agreement on Coal Seam Gas and Large Coal Mining Development in June 2012. The government also committed to improving the consideration of land-use issues in approval processes by strengthening policy and legislation. In late 2013, the moratorium was expanded to halt all new onshore gas exploration approvals—for conventional or unconventional sources—until at least July 2015.

In between these moratorium announcements the government also committed to conducting public consultation and groundwater science studies, to better understand the risks. In November 2014, legislation was enacted banning the use BTEX chemicals—known to be toxic—in exploration and production activities.

The current government extended the moratorium until risks are properly understood and protection of the ground and surface water can be ensured. In January 2015 it announced a Parliamentary Inquiry into issues surrounding unconventional gas exploration and production, which is due for completion by December 2015.

This has mirrored similar approaches in other states. All states and territories except the Australian Capital Territory have conducted a substantial inquiry or review into unconventional gas since 2011 and two other states also imposed moratoria—NSW in 2011 and Tasmania in 2014. The NSW moratorium was lifted in 2012 following the outcome of the NSW inquiry. Several other jurisdictions have imposed moratoria or banned unconventional gas and/or hydraulic fracturing activities completely, including Germany, France, Scotland and some American states.

1.2.4 Issues for consideration in Victoria

There are three core areas of potential impact of onshore unconventional gas activities in Victoria—economic gain, social and industry impact and environmental risk. Victoria has a relatively small land mass, a high population and strong economic dependence on the agricultural sector. This creates significant challenges for developing an unconventional gas industry.

A key challenge is that the most likely areas for commercial unconventional gas production underlie prime agricultural land. There is a widespread perception that these industries have fundamentally conflicting interests.

These are also areas where the sustainable use of groundwater by existing industries, towns and farms is already reaching or at the identified limit that still leaves enough groundwater to maintain dependent ecosystems. Existing and past activities have adversely affected the quality of the groundwater in many locations.

Community concern about the potential risks posed by unconventional gas activities also presents challenges. Concern has been increasing in Victoria since around 2010, when hydraulic fracturing became prominent both nationally and internationally following the release of the documentary Gasland and reports of potential environmental and health impacts—including from CSG production—in Queensland and NSW. At the same time, a significant body of scientific literature indicated that environmental impacts can be managed if best practice is adhered to. However this has done little to reduce community concern.

By 2010, commercial production of onshore conventional gas had been underway in Victoria for almost 20 years but had not raised similar levels of concern.

In Victoria, community concern is apparent in the number of community meetings on these issues and local councils opposing CSG or unconventional gas more broadly. For example, the State Council of the Municipal Association of Victoria resolved in May 2014 to oppose any CSG exploration or production within the state. Recently the Victorian Farmers Federation has publically stated that the ban on hydraulic fracturing should remain in place until at least 2020 while more information is gathered on the potential risks of an unconventional gas industry.

Food, water and energy security are all important. Each relies on and competes for the state's natural resources, particularly ground and surface water. The government now has the opportunity to carefully evaluate the full range of issues, risks and impacts associated with an unconventional gas industry and consider how these can be best managed so as not to jeopardise Victoria's economic, environmental and social sustainability.

1.3 The regulatory system

This audit has considered the regulatory system for unconventional gas as encompassing two aspects:

- the direct earth resources policy and legislation and all the associated tools including codes of practice, licences, permits and guidelines

- policy and legislation for managing environmental values and impacts and land-use planning more generally, such as state environment protection policies and water legislation.

1.3.1 Policy

The Australian Government's 2015 Domestic Gas Strategy identifies that the states are primarily responsible for regulating onshore gas resources in their jurisdictions, and it expects them to support the development of the unconventional gas industry, using strong scientific evidence to underpin any decision.

DEDJTR's 2014 Earth Resources Statement identified that the moratorium would extend until at least July 2015 and that government policy would continue to be informed by independent scientific facts and public consultation, and would recognise the economic importance of the agriculture sector.

The current government has not continued with the actions identified in this statement and has not released a replacement strategy. A media release stated that the Parliamentary Inquiry into unconventional gas aimed to be 'a thorough and considered inquiry into onshore gas in Victoria, based on robust scientific evidence and community engagement'.

1.3.2 Legislation

Victoria directly regulates onshore unconventional gas activities through two Acts:

- the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990(Minerals Act) regulates CSG exploration and production

- the Petroleum Act 1998(Petroleum Act) regulates shale and tight gas exploration and production.

These Acts are administered by the Minister for Energy and Resources through DEDJTR, formerly the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation and before that, the Department of Primary Industries. The objectives of both Acts include minimising adverse environmental and community impacts.

There are at least 52 other acts and a vast array of associated regulations, policies and guidelines that indirectly regulate the environmental and social impacts of unconventional gas activities. These include the Planning and Environment Act 1987, the Environment Effects Act 1978, the Environment Protection Act 1970, the Water Act 1989 and the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978.

1.3.3 Roles and responsibilities

There are two departments with the primary responsibilities for unconventional gas. There are also a number of agencies responsible for discrete aspects, related to the various Acts that indirectly regulate unconventional gas.

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources

DEDJTR is responsible for managing the earth resources sector through the responsible and sustainable allocation and regulation of earth resources that provide financial benefits and meet the economic, social and environmental objectives of the state. This includes licensing unconventional gas exploration and production, approving plans, assessing environmental impacts as part of approval processes, and monitoring and enforcing industry adherence to regulation. It also collects royalties from mineral and petroleum production.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning's (DELWP) main roles relating to unconventional gas are:

- advising the Minister responsible for Crown land on licence applications covering Crown land and requests for access to Crown land

- supporting the Minister for Planning in deciding whether onshore gas production applications require an environmental effects statement (EES) and administering the EES legislation and inquiry process

- developing a strategic land-use policy to better manage competing land uses in Victoria, such as mineral or petroleum production and agriculture

- in partnership with water corporations and catchment management authorities, managing Victoria's water resources, including extraction, licensing and discharge

- advising the minister responsible for water on water resources including planning and entitlements.

Other agencies

Exploration and production activities are exempt from Environment Protection Authority (EPA) approval and licensing unless they continually discharge waste waters. However, the EPA still plays a key role in advising DEDJTR on appropriate licence conditions to manage the environmental risks of mineral or petroleum production activities. It can also regulate pollution events, or events that pose a serious risk of harm to health or environment.

Rural water corporations licence surface and groundwater extraction and replacement for the commercial production of unconventional gas, associated infrastructure and disposal of matter underground.

The Victorian Mining Warden is appointed by the Governor in Council under the Minerals Act, as an independent statutory officer. The warden can investigate issues and disputes, about the existence of a licence or the boundaries of a licence or licence application, between a licensee and DEDJTR, landowners, another licensee or a member of the public.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit examined whether Victoria is well placed to effectively respond to the potential environmental and community risks and impacts of onshore unconventional gas activities in the event that these proceed in this state.

The audit did not focus on onshore conventional gas activities and did not examine processes that can transform solid coal into gas.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit assessed previous unconventional gas activities covered by the Minerals and Petroleum Acts. This included DEDJTR's administration, application, monitoring and enforcement of the regulatory requirements for these activities and DELWP's roles relevant to water management and planning.

The audit also consulted with a range of eminent experts and reviewed national and international literature on unconventional gas to identify the issues, risks and impacts that have been identified to date. It examined other state and international policy and regulatory systems for managing and monitoring unconventional gas risks and impacts, to identify better practice.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $525 000.

1.6 Structure of this report

The report has three further parts:

- Part 2 examines what is known about the potential risks and impacts from unconventional gas activities in Victoria and how these have been addressed

- Part 3 examines how effectively the existing regulatory framework has been applied to the unconventional gas exploration activities that have occurred to date

- Part 4 identifies opportunities to improve the planning that informs the release of areas for exploration and better manage the challenges posed by unconventional gas if an unconventional industry is supported in Victoria.

A glossary of uncommon terms used throughout this report is included in Appendix B.

2 What are the risks?

At a glance

Background

A comprehensive body of literature and interstate and overseas experience has illustrated the potentially significant risks and impacts of unconventional gas resource development. A risk management approach is required to assess their relevance to Victoria.

Conclusion

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) has not yet developed a comprehensive risk management approach to identifying the potential risks of unconventional gas activities in Victoria. This is due to a moratorium being put in place, the resource potential of this source of gas being unknown and the limited activity to date. However, this is a missed opportunity as there have been numerous chances for the department to collate the data and knowledge around risks, to ensure future decisions are evidence based and timely.

Findings

- The potential of unconventional gas resources in Victoria is unknown.

- The risks associated with unconventional gas activities in Victoria have not been comprehensively identified, prioritised or assessed.

- DEDJTR's approach to collating intelligence around the risks posed by unconventional gas activities in Victoria has significantly improved since 2012. Since then, DEDJTR has focused on understanding community concerns.

- The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) has focused on identifying risks to water resources.

- Knowledge gaps remain about risks to the landscape, land use, air quality and human health.

Recommendations

DEDJTR, in partnership with DELWP, develops a comprehensive risk management strategy for unconventional gas activities in Victoria.

2.1 Introduction

Overseas and interstate literature and experience has illustrated the potentially significant risks and impacts associated with an unconventional gas industry. This has made the development of unconventional gas resources extremely controversial both here in Victoria and elsewhere.

A risk management approach is required to identify and prioritise the risks relevant to Victoria, to assess their associated impacts and to identify appropriate controls to mitigate medium and high risks to an acceptable level. The development of a comprehensive risk management strategy is the first step in developing such an approach as it identifies the risks, their likelihood and their consequences.

2.2 Conclusion

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) and its predecessors have not implemented a systematic and comprehensive approach to assess all the risks associated with unconventional gas activities in Victoria. While it has identified and assessed the key risks to water resources—with the assistance of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP)—it has not identified all potential sources of harm from unconventional gas activities. It has not transparently documented its rationale to its staged approach to the assessment of all potential risks, or identified and prioritised further stages of work required to inform a decision in relation to the moratorium.

When exploration activities began in the early 2000s, DEDJTR did not analyse what information it had to determine what it needed to adequately assess the potential environmental and social risks and impacts associated with these activities.

Between 2000 and 2012, when unconventional gas exploration activities were approved, DEDJTR's response to identifying and assessing the risks was slow, informal and ad hoc. After 2012, its approach significantly improved but gaps still remain. There is no clear documented rationale explaining its staged approach to the assessment of risks. Gaps in information and analysis still remain in terms of identifying all potential risks that require assessment.

DEDJTR's approach and activities to identify broad community concerns has been comprehensive. It has made good progress in partnership with DELWP in identifying and assessing the key risks to water resources. However, this has occurred outside of the development of a comprehensive desktop risk management strategy that identifies DEDJTR's approach to assessing all potential risks, its rationale to its staged approach and the identification and prioritisation of works to identify and assess key potential risks. These include potential risks to current land uses, the landscape and its values, human health and air quality.

This has further delayed the identification of priority actions, the collection of data and knowledge needed to inform the decision in relation to moratorium and the sustainability of an unconventional gas industry in Victoria. Making evidence-based decisions was one of key aims of the moratorium since 2012.

2.3 How has DEDJTR informed itself and government of the risks?

The Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 and Petroleum Act 1998 require both the environment and communities to be protected from risks associated with unconventional gas activities. This requires the regulator to undertake a comprehensive approach that identifies and assesses all known and potential risks. This involves three steps:

- risk identification and assessment

- risk management

- risk communication.

The first step—risk assessment—involves an assessment to identify potential and known sources of harm, followed by an assessment of the likelihood that harm will occur, and the consequences or impacts if it does occur. Risk management refers to evaluating which risks require management based on their likelihood and consequence, and selecting and implementing the plans or actions that may be taken to ensure that those risks are controlled. Risk communication involves an interactive dialogue between stakeholders, risk assessors and risk managers.

A risk management strategy forms the key basis of the regulator's overall approach to identifying, assessing and managing risk and communicating its approach to achieving this. A strategy transparently communicates the context for the regulator's work and its decisions.

DEDJTR does not have a documented risk management strategy or any other document that transparently outlines its approach to identifying and assessing the potential and known risks of unconventional gas activities. Although it has undertaken a gated and staged approach since 2013, the scope of work required to identify the potential risks and the staging of its work has not been identified or clearly documented.

Victoria's unconventional gas industry was in its infancy in Victoria prior to the 2012 moratorium which put a halt to all new coal seam gas (CSG) activities. The intent of the moratorium was to assist the government to make an evidence-based assessment of the viability and sustainability of such an industry in Victoria.

As there is currently no unconventional gas activity in Victoria it is not expected that DEDJTR complete all three steps of a risk management process. However, it is reasonable to expect that DEDJTR would comprehensively identify and document all potential risks from unconventional gas activities, prioritise these for assessment and identify the scope of work required to complete this.

To adequately do this, DEDJTR needs to undertake a desktop review of all current literature and information to identify gaps and what needs to be done to fill these gaps.

Before a decision is made on the moratorium a comprehensive assessment of the likelihood and consequences of all potential risks should be undertaken. This should be supported by analysis of whether best practice controls can manage high risks to acceptable levels. These steps and their outcomes must be transparently communicated to all stakeholders.

2.3.1 Prior to 2010

Prior to 2010 the former Department of Primary Industries and its predecessor, the former Department of Natural Resources and Environment—now DEDJTR—conducted only limited and ad hoc activities to collect and analyse data and information to build its knowledge around the potential risks in Victoria. It adopted a deliberately light-handed approach to the identification of risks because:

- evidence and concern about the risks and impacts of this industry was only slowly emerging globally

- it considered that the number of activities, and therefore overall risk of this industry relative to other earth resource industries, was low

- the exploration activities approved were deemed to be manageable under the current regulatory system

- the interest in developing this resource in Victoria was low and there were no production activities

- it believed that its regulatory practices represented good practice and met international standards.

However, DEDJTR did not validate its assumptions where environmental risks were concerned. It also did not collate information and data to identify gaps around the potential risks.

There was a flurry of new licence and work applications to explore for CSG from the late 1990s to the first half of the 2000s. DEDJTR continued its established process of offering onshore areas with potential resources for tender, which allowed exploration for tight and shale gas. Departmental briefings show CSG was first raised as an issue with the relevant minister in 2003 and 2004 mainly due to a perceived growing demand for CSG as a potential energy source. Briefings indicated that CSG was a new industry with new processes that posed new risks. DEDJTR did not propose actions to further identify and assess these risks, even though multiple exploration and hydraulic fracturing proposals had been approved.

The Minister for Energy and Resources' 2004 Ministerial Statement supported the development of CSG. Its commitment to review legislation only related to ensuring it did not present barriers to the exploration of this resource. The statement did not raise the issue of identifying or addressing the risks associated with CSG. The overall assumptions relied on by DEDJTR during this time were that the production of CSG was unlikely in the short term and that the current level of unconventional gas exploration activities represented a generally lower risk than other earth resources industries at the time.

The risks of unconventional gas exploration activities vary dependent on the resource, the area and the activity. Drilling deep into rock layers that are not adequately mapped, as part of tight and shale gas exploration, involves significant uncertainty and therefore inherent risk. CSG exploration can also involve drilling several wells that can be active for months during which a significant amount of groundwater needs to be extracted to release the gas. Hydraulic fracturing, which has been used in exploration in Victoria, can be high risk where there is an absence of good baseline data.

DEDJTRs approach did not improve even in the face of increasing public awareness about the risks of unconventional gas both here in Australia and overseas. It did not brief the relevant minister on unconventional gas development in Victoria from 2004 until 2011.

2.3.2 Between 2010 and 2012

Between 2010 and 2012, unconventional gas caught the attention of the Victorian community. There was a lot of focus on hydraulic fracturing nationally and internationally following events such as the release of the 2010 documentary Gasland. There was also increasingly vocal community concern about the impacts of hydraulic fracturing for CSG in Queensland and New South Wales (NSW).

A number of comprehensive international studies emerged identifying the challenges and risks of unconventional gas activities. Victorian and Australian concerns were focused on CSG because it was the predominant target of onshore gas exploration and production. Hydraulic fracturing is often not required for CSG—only one in eight wells in Queensland use hydraulic fracturing—compared to tight and shale gas where it is always required.

In 2011, the Council of Australian Governments saw the need to develop nationally consistent practices to manage the risks related to CSG. The first step in this process was to identify all the potential risks.

DEDJTR actively engaged with other states and the Commonwealth to build its knowledge around the risks and challenges posed by CSG extraction. This was evidenced by:

- its contribution to the Council of Australian Governments' National Harmonised Regulatory Framework and Multiple Land Use Framework working groups

- DEDJTR initiating its own CSG working group with the then Department of Sustainability and Environment and the Environment Protection Authority to identify water risks and issues.

However, the data and intelligence obtained from these initiatives was not centrally collated, analysed or used to inform a better approach. The knowledge obtained did little to change DEDJTR's or the government's approach and attitude to understanding or managing the risks of unconventional gas activities.

This was evidenced in its 2011 briefing to the Secretary on the risks of hydraulic fracturing and the associated community concerns. It identified potential environmental risks and issues, particularly in relation to groundwater, land-use conflicts and the potential for earth tremors as a result of hydraulic fracturing activities. However, it advised that no policy or regulatory response was required to address these risks because:

- it deemed the objective-based regulation in place required all key risks to be identified and managed and as such provided sufficient environmental protection

- DEDJTR considered that it had equivalent processes to those introduced in Queensland to assess and manage risks

- the early stage of the industry in Victoria did not warrant more detailed consideration of risks—this was to be reconsidered should any commercial activities be proposed.

Again, this advice was not based on any review, benchmarking or other validation process that the identification and management of risks elsewhere meant they could be managed well here.

2.3.3 Since 2012

Since late 2012, DEDJTR significantly improved its processes and effort to identify the risks of unconventional gas and used this to inform its decision-making and advice. This was done in response to increasing community concern, state and national reviews, national initiatives to improve the management of CSG and the introduction of the Victorian moratorium.

DEDJTR conducted reviews, consulted more broadly and actively identified the work required to identify a number of the key risks and community concerns. These were seen as key steps in informing the government's decision around a decision in relation to the moratorium. Successive state governments, however, placed much of this work on hold out of concern that it could be seen to pre-empt a decision to lift the moratorium.

The moratorium was introduced in 2012 for CSG and expanded in 2013 to include tight and shale gas. It was introduced to allow time for information and data to be gathered to develop a sound understanding of the risks and impacts of onshore unconventional gas activities so an informed decision could be made at the end of its period. Work focused on assessing impacts to resources and identifying key community concerns. DEDJTR commenced a program in late 2012 to engage with a wide range of stakeholders. As part of this process it initiated, participated in and responded to a range of Commonwealth and state reviews and working groups.

Key actions included:

- participating in the 2013 National Partnership Agreement on Coal Seam Gas and Large Coal Mining Development

- responding to recommendations made by two key Victorian inquiries: the Economic Development and Infrastructure Committee of Parliament's 2012 Inquiry into greenfields mineral exploration and project development in Victoria(the EDIC inquiry) and the former government's 2013 Gas Market Taskforce

- responding to recommendations made by the Earth Resources Ministerial Advisory Council established to advise the Minister for Energy and Resources on key matters of relevance to earth resources industries.

A number of key studies and initiatives were put in place in 2013 to further DEDJTRs understanding of the risks and concerns. DEDJTR is mainly responsible for delivering these commitments, although DELWP has key roles as well. These initiatives include:

- a 12-month community engagement program—DEDJTR

- major water science studies—DELWP

- the Gippsland basin bioregional assessment, managed by the Commonwealth Government.

These latter studies focus on key water resource risks even though an increasing body of national and international literature identified key risks to biodiversity, the landscape, air quality—including greenhouse gas emissions—and human health.

Community engagement and identification of risks

If unconventional gas development proceeds in Victoria it is likely to have a significant impact on land owners and local communities, as this has occurred in all other areas world-wide where such an industry is present. Unconventional gas resources tend to be located underneath land with other high-value uses, such as agriculture, as seen in the Gippsland and Otway basins. This can create opportunities for both industry and landowners, as it is possible to have both unconventional gas and agriculture in the same location. It can also potentially generate land-use conflict and social impacts, particularly around land access, and the liveability and amenity of areas.

Landowners may experience increasing competition for natural resources, such as land and water. Neighbouring communities may experience other negative impacts from unconventional gas activities including dust, noise, increased traffic and landscape visual impacts. Compared to conventional gas developments many more landholders are likely to be affected due to the large area both above and below ground that may be impacted by the industry.

Victoria has been slow to engage with the community on unconventional gas information and issues. This need was recognised since at least 2006 when industry pushed for government to provide more information. The EDIC inquiry also recommended consultation in 2012. Limited consultation started soon after this, but was interrupted when the moratorium was introduced.

Community engagement recommenced in 2014 following a government commitment to do so, and was reported on in 2015. It was comprehensive and led by DEDJTR and aimed to understand community views, concerns and risks in relation to an unconventional gas industry in Victoria. The approach used for the community engagement program largely met the better practice elements of VAGO's 2015 better practice guide on Public Participation in Government Decision-making.

However, it did not include a clear description of the decision to be made following the consultation, nor did it adequately advertise meetings. Meetings were advertised in local papers, which was inadequate given the extent of electronic social media options and other traditional means, such as the use of peak bodies and town notice boards.

The results identified polarised opinions on onshore gas. Up to 46 per cent of those surveyed opposed an industry in areas where unconventional gas activities are most likely to occur, while a large proportion of the community—44 per cent—remained undecided.

Those opposing the industry tended to focus on environmental and community risks and those supporting, on economic benefits. The key concerns of those opposing unconventional gas included:

- the need for the industry has not been established

- there are potentially substantial, long-lasting and unacceptable risks to the landscape, regional character and natural resources—particularly groundwater, agricultural productivity and biodiversity

- there are many risks and potential long-term costs, for likely shorter-term gain

- there is a high level of scientific uncertainty about what the risks are for Victoria and the successful management of these

- the system is not fair, as landholders cannot veto exploration or production and do not have equivalent negotiating power for compensation and rehabilitation

- public health concerns

- poor capacity of the regulators and regulatory system to manage the impacts.

There was a high level of agreement about the need for government control and more information. Those supporting the industry believed that there was significant misinformation about some of the potential risks and impacts and that information sources about risks lacked credibility.

Providing the community with more independent, peer reviewed scientific information that is transparent and accessible should assist people who do not have an opinion to form one. This is a key aim and outcome of developing a risk management strategy. It also provides assurance to those concerned that the risks have been comprehensively identified and assessed and can be appropriately managed if an industry proceeds.

Water science studies

There are a number of significant water science studies underway in Victoria to examine the possible impacts of an onshore natural gas industry on Victoria's surface and groundwater resources in the Gippsland and Otway basins.

The 2015 $10 million bioregional assessment of the Gippsland Basin is being conducted by the Commonwealth agencies with DELWP and DEDJTR receiving $2.4 million to conduct the Victorian work. The focus of this assessment is to better understand the possible impacts of CSG and coal mining developments on above and below ground water resources and assets. This assessment is limited to the groundwater systems close to the surface, not the deeper groundwater systems potentially impacted by tight and shale gas exploration.