Quality of Child Protection Data

Snapshot

Does the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) have adequate controls to ensure that data in its Client Relationship Information System (CRIS) is reliable?

Why this audit is important

CRIS is a critical data system. Its purpose is to store sensitive information about vulnerable Victorian children. It is central to how DFFH delivers its child protection services.

DFFH needs to make sure that CRIS data is high quality so it can fulfil its obligations to vulnerable children and support its policies and decisions.

Who and what we examined

We assessed if DFFH:

- manages child protection data in line with relevant guidelines

- has appropriate controls to make sure child protection data is complete, accurate and recorded in a timely way.

What we concluded

DFFH does not have adequate controls to ensure its child protection data is of high quality.

We found examples of incomplete, inaccurate and inconsistent data. This means that DFFH may not have easy access to reliable data to help it make decisions about vulnerable children.

These data quality issues may also prevent DFFH from using the data to monitor children's progress in out of home care.

The factors that contribute to poor quality data include:

- DFFH's child protection data does not comply with government data quality standards

- CRIS is not fit for its intended purpose and its data quality controls do not always work

- the workloads of CRIS users limit their capacity to correctly record information about children in a timely way.

DFFH told us that it is aware of these issues and is working on a plan to address them.

What we recommend

We made 3 recommendations to DFFH about improving the quality of child protection data.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO.

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) and considered its views when reaching our conclusions. DFFH’s full response is in Appendix A.

DFFH’s CRIS data is not always up to date or accurate

We refer to children and young people throughout this report as 'children' for simplicity.

DFFH stores and manages a significant amount of information on vulnerable children in its Client Relationship Information System (CRIS).

This information is key to help DFFH:

- make decisions about the type of care a child receives

- better understand issues that affect vulnerable children and their families

- deliver child protection services.

When we analysed CRIS data in our June 2022 Kinship Care audit, we found that it was not always up to date or accurate.

This audit confirmed that DFFH’s child protection data does not readily give the most current and complete information on vulnerable Victorian children. It also does not consistently provide an auditable trail of information to confirm that DFFH’s decisions are always in a child’s best interest.

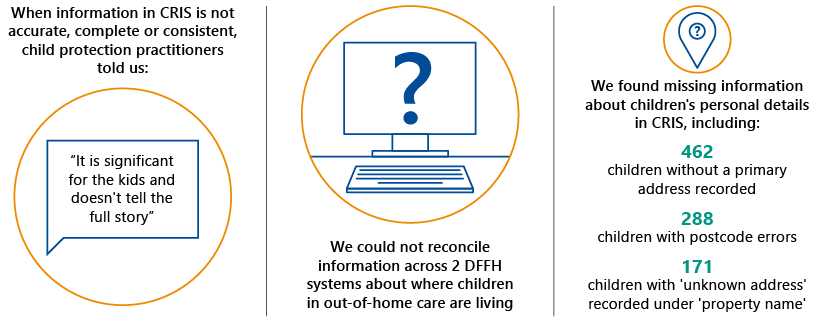

Figure A outlines some of the issues we found with incomplete, inaccurate and inconsistent data.

Figure A: Examples of incomplete, inaccurate and inconsistent data

| Issues we found | Potential impact of poor-quality data |

|---|---|

| Incomplete data | |

|

We found gaps in children’s personal details, including their dates of birth and addresses. |

This limits DFFH’s ability to:

|

|

We found 155 instances where DFFH had not updated the outcome following a court event relevant to a child’s welfare. |

This puts the child at risk of having contact with a person that the court order does not allow. |

|

We found gaps in children’s health information, such as:

|

This puts children at risk of not receiving the medical care or intervention they need. |

| Inaccurate data | |

|

We found an instance where a child’s file showed that they attended their first year of school for over 10 years. |

This means that DFFH may not have an accurate understanding of children's education statuses. |

|

We found 261 instances where a child’s recorded education end date was before the education start date. |

|

| Inconsistent data | |

|

We found that there are up to 437 more placements recorded in DFFH’s carer payment system than in CRIS. |

There is a risk that DFFH is making payments to people who are not caring for children in out-of-home care. |

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

CRIS users record most information in case notes, not searchable fields

Child protection practitioners are DFFH staff who provide child protection services. Caseworkers are staff from external service providers who DFFH contracts to provide child protection services.

Child protection practitioners and caseworkers record most information about children in case notes, which are free-text fields in CRIS.

Case notes are an integral part of any case management system. But CRIS case notes are not structured in a way that lets users easily record, find or access critical information.

This means there is a risk that staff may not be able to access essential information later on (if it has been recorded in the first place).

CRIS has multiple fields where users can record essential information about children.

DFFH and child protection managers could easily access data in these fields for reporting purposes.

However, moving this information from case notes to these fields would duplicate child protection practitioners’ work and they already have a heavy workload. It may also increase the risk of errors.

DFFH told us that it is actively working on enhancing CRIS and relevant data systems to address the issues we identified in this report. It also said that it is redeveloping its carer payment processes, policy and technology.

Other elements of DFFH’s decision-making processes are insufficient

DFFH told us that while CRIS is its key source of child protection data, it is only one element of its decision-making process.

It explained that it relies on other sources and quality assurance processes to make sure its child protection decisions are sound, including:

- its Child Protection Manual

- practice frameworks and guidance

- professional judgement.

It also has processes where team managers must endorse child protection practitioners’ decisions at certain stages of the child protection process.

However, these processes are not a substitute for high-quality data because inaccurate or incomplete data may misinform supervisors’ decisions.

Additionally, DFFH requires staff and team managers to have one to 2 hours of supervision discussions per fortnight. However, its Child protection and family services: Additional service delivery data 2020–21 report found that this is only happening 58 per cent of the time.

DFFH told us:

'In addition to formal one-on-one supervision, child protection practitioners also receive unplanned supervision and group supervision. These less-formal types of supervision are not recorded or captured in the supervision data recording system'.

Factors that contribute to poor-quality data

Our review of DFFH's child protection data and CRIS's design, business processes and current validation and quality controls found that CRIS is not fit for purpose.

CRIS is a legacy system that has not kept pace with technology and sector changes.

For example, unlike contemporary systems and applications, CRIS does not communicate and integrate with DFFH’s other important systems, such as its carer payment system.

We have sighted documentation seeking government funding for DFFH's technology reform for its data systems, including for its child protection data.

Other factors that contribute to DFFH's poor-quality child protection data include:

- DFFH has not complied with government data quality standards

-

many of CRIS’s data quality controls are ineffective, including its user access controls

- child protection practitioners have limited capacity to update CRIS data.

DFFH has not complied with government data quality standards

The Data Quality Standard outlines 7 data quality dimensions to ensure data is accurate, complete, timely, representative, collected consistently and fit for purpose. See Figure 1C for more information about the dimensions.

The Victorian Government’s 2018 Data Quality Information Management Framework Standard (Data Quality Standard) requires Victorian Government departments to 'establish and maintain a standard of quality for critical datasets'.

The Data Quality Standard also says that a dataset is 'of sufficient quality if it is fit for purpose and correctly represents the real world situation to which it refers’.

The Data Quality Standard sets minimum requirements for Victorian Government departments to follow, including:

- assessing critical datasets against the data quality dimensions

- having a data quality statement that outlines any known data quality issues

- developing a data quality management plan to address these issues

- making sure it has accountable officers that are responsible for data quality.

However, contrary to these requirements:

|

DFFH has not … |

This means that DFFH cannot … |

|---|---|

|

assessed its child protection data against the quality dimensions. |

|

|

prepared a data quality statement. |

help users decide if the data is fit for its intended purposes. |

|

developed a data quality management plan. |

systematically plan to:

|

DFFH has accountable officers who are meant to be responsible for the quality of its child protection data. These officers include a data steward, custodian, and administrator.

However, DFFH has not clearly articulated how these officers are meant to work together to do this role.

DFFH’s noncompliance with the Data Quality Standard’s minimum requirements also means that its accountable officers have not effectively performed their data quality management responsibilities.

DFFH told us that it is aware of these issues and is working to address them.

For example, DFFH told us that since this audit started, it has:

- started assessing the quality of its child protection data and developing its data quality statement and management plan

- clarified its accountable officers’ responsibilities. Its data custodian is now responsible for managing data quality.

Some of CRIS’s data quality controls are ineffective

Kinship care is when a child who cannot live with their parents is placed in a relative or family friend’s home. When a placement starts, DFFH must do an assessment to check the placement’s safety, stability and appropriateness.

Part A kinship assessments check if a kinship placement is safe when it starts. These assessments must be completed within 7 days of a placement starting.

Part B kinship assessments assess what support the carer and child need for a safe and stable home. These assessments must be completed within 6 weeks of a placement starting.

DFFH could not give us a full list of CRIS’s data quality controls.

Of the controls that we were able to identify and review, we found that some do not effectively identify and prevent data quality issues.

For example, CRIS has some mandatory fields. If a field is mandatory, a user must fill it before they can save or proceed with a file. Some examples of mandatory fields in CRIS are criminal record checks for kinship carers and their adult household members.

However, we found multiple instances where mandatory fields were not filled in CRIS.

DFFH also has some data validation controls to confirm that recorded information makes sense.

However, we found that some of these did not work. For example, we found instances where the recorded start date for a part B kinship assessment was before the part A kinship assessment was completed.

CRIS has weak user access controls

Weaknesses in DFFH’s user access controls mean that staff who are no longer authorised to log into CRIS may still be able to access sensitive information about children and record or revise entries for their previous clients.

This could potentially affect the accuracy and reliability of child protection data.

DFFH told us that when staff leave (including internal DFFH staff and external caseworkers) their manager must request to deactivate their CRIS access.

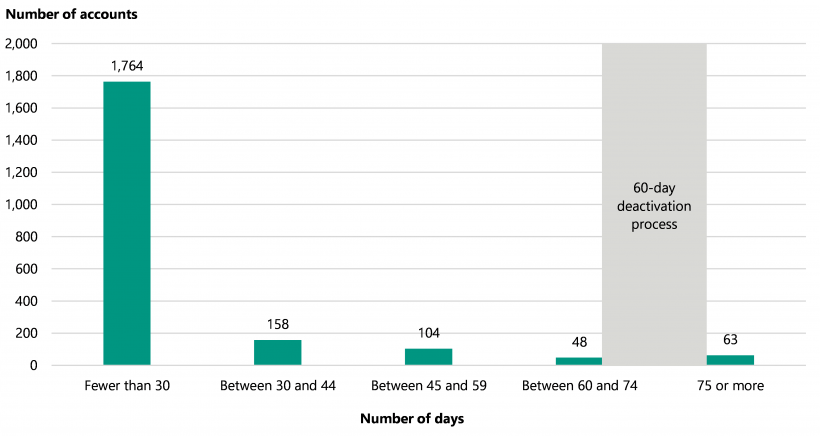

DFFH also told us that it automatically deactivates internal staff members’ access when they have not logged into CRIS for at least 60 days.

However, our review of available data found that at least 63 users who had not logged into CRIS for 75 days or more continued to have access.

This means that staff who are no longer authorised to access CRIS may continue to log in.

Users have limited access to ongoing training and guidance

CRIS is a complex system, so DFFH must give users access to ongoing training and guidance to understand:

- how to create, access and update CRIS files

- DFFH’s expectations for record keeping.

DFFH offers limited ongoing training for:

- child protection practitioners about CRIS

-

external caseworkers about the Client Relationship Information System for Service Providers (CRISSP), which is linked to CRIS.

CRISSP is a separate data system that external service providers use.

While this has been partly due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, DFFH has transitioned some training courses online.

DFFH has an extensive range of guidance documents that outline CRIS processes.

However, we heard through our interviews with staff that these documents are not always easy to access.

Given the workload pressures that child protection practitioners often face, easy access to guidance and support is critical.

Child protection practitioners have limited capacity to update CRIS data

To make a report to child protection services, a person needs to have formed a reasonable belief that a child has suffered or is likely to suffer significant harm due to abuse or neglect and their parents have not protected or are unlikely to protect them from this harm.

When a report is substantiated it means that an investigation has found that there is reasonable cause to believe that a child was, is being or is likely to be abused, neglected or otherwise harmed.

High case loads and the growing demand for child protection services in Victoria limit child protection practitioners’ capability to update CRIS files in a timely way.

Demand for child protection services

Nationally, the number of children named in child protection reports and substantiated reports has steadily increased over the last 5 years.

The growing demand for child protection services puts pressure on child protection practitioners. It also affects their ability to update their clients’ CRIS files in a timely way.

High case loads and cases awaiting allocation

On average, each child protection practitioner has a median of 15 allocated cases that involve vulnerable children and their families.

A case’s complexity may impact how much time the child protection practitioner needs to update it.

DFFH also requires child protection practitioners to do tasks for cases waiting to be allocated. This includes updating CRIS files.

Data from DFFH suggests that there were 3,130 vulnerable children waiting to be allocated to a child protection practitioner as at 25 May 2022.

Recommendations about improving the quality of child protection data

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

1. as required by the Data Quality Information Management Framework Standard and Data Quality Guideline Information Management Framework:

|

Accepted |

|

2. undertakes a training needs analysis to understand and address current and potential gaps in child protection practitioners’ knowledge and capability to appropriately use the Client Relationship Information System, including by:

|

Accepted |

|

|

3. determines and advises the government on the workforce resources it needs to:

|

Accepted |

1. Audit context

The Victorian child protection system aims to protect children when their families are unable or unwilling to care for them.

CRIS is a critical data system that is central to how DFFH delivers the state’s child protection services.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Child protection in Victoria

Under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005, DFFH can assess and intervene when it receives a report that a child needs protection. It can do this by:

- investigating an allegation that a child is at risk of significant harm

- referring children and families to services for their safety and wellbeing

- applying to the Children’s Court of Victoria (Children’s Court) if it cannot ensure that a child is safe with their family

- administering protection orders granted by the Children’s Court.

The child protection process has 5 stages where child protection practitioners and external caseworkers collect, store and use critical information about children.

|

In the … |

Child protection practitioners and external caseworkers … |

|---|---|

|

intake stage |

open a case in CRIS to record reports about a child not being safe. |

|

investigation stage |

investigate and decide if the child needs protection. |

|

protective intervention stage |

work with families to assess, plan and refer them to support services with a focus on:

|

|

protection order stage |

create a case plan for each child and make sure it reflects court orders. |

|

closure stage |

do a final risk assessment to confirm that the decision to close a case is sound. |

1.2 Child protection data systems

According to the Productivity Commission, which provides independent advice to the Australian Government on issues that affect the community, good-quality data is a key factor in how effectively government agencies deliver child protection services.

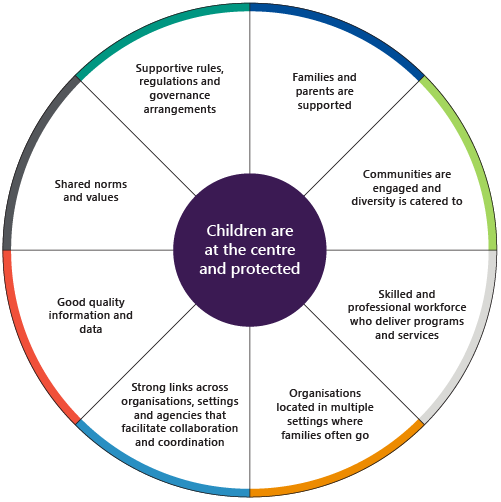

Figure 1A shows the Productivity Commission's key characteristics for an effective child protection system.

FIGURE 1A: Key characteristics for an effective child protection system

Source: VAGO, based on the Productivity Commission.

The Report on Government Services is a public report on how Australian state governments are performing and delivering important services to their communities.

High-quality child protection data can help DFFH:

- identify and address gaps in its services

- assess the effectiveness of its child protection programs

- contribute to the Child Protection National Minimum Dataset, which the Productivity Commission uses for its Report on Government Services.

CRIS

CRIS is DFFH’s main data system for child protection services. It has been in place since 2005.

DFFH uses CRIS to record sensitive information about children in out-of-home care. Data management systems such as CRIS, if fit for purpose and used appropriately as intended, can provide an auditable trail of information to support DFFH’s decisions about children’s welfare.

Child protection practitioners use CRIS daily. DFFH also regularly uses it to inform its policy, funding and strategic decisions. However, it is not a predictive or structured decision-making tool.

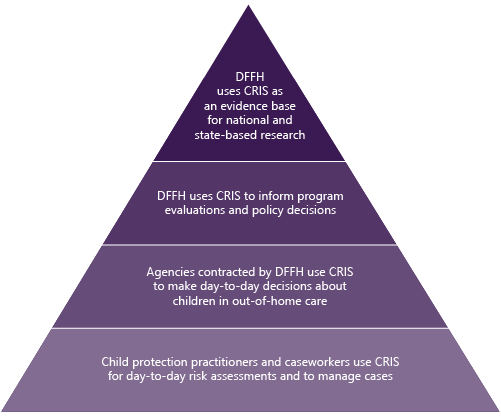

Figure 1B shows the main uses for CRIS data.

FIGURE 1B: Main uses for CRIS data

Source: VAGO.

DFFH also uses CRIS data to measure the capacity and capability of its out-of-home care services.

For example, CRIS data informs a number of statewide performance dashboards and reports that DFFH regularly uses to understand and address service gaps.

Other tools and data systems

DFFH told us that CRIS is one of many tools that child protection practitioners use to make decisions. They also use:

- DFFH’s Child Protection Manual

- DFFH’s frameworks and guidance (including the 2021 SAFER Children Framework Guide and 2012 Best interests case practice model)

- CRIS user guides

- training and development

- professional supervision

- professional judgement.

DFFH also uses other data systems to monitor how children progress in the child protection system, including:

|

The … |

Which is … |

|---|---|

|

Client Relationship Information System for Service Providers |

the system that external caseworkers contracted by DFFH use to record information about children in out of home care. |

|

Front-End Reception Information System |

the system that DFFH’s reception staff use to look up child protection practitioners and caseworkers to make appointments or request contact. |

|

carer payment system |

a corporate finance system that DFFH uses to make payments to carers who look after children in out-of-home care. |

|

Client Incident Management System (CIMS) |

the system that child protection practitioners and caseworkers use to record and report on incidents involving children in out-of-home care. |

|

Integrated Reports and Information System |

the system that DFFH’s Child FIRST (family information, referral and support teams) and family services teams use to record information about their clients and services. |

Appendix D shows how these systems work together and form DFFH’s Integrated Client and Case Management System (ICCMS).

1.3 Data quality standards and guidelines

Victorian Government’s Data Quality Standard

As a critical dataset, DFFH’s child protection data must comply with the Victorian Government's Data Quality Standard.

The Data Quality Standard sets out the minimum requirements that departments must follow to make sure their critical datasets meet quality standards. It says that departments ‘must at a minimum’:

- have a dataset custodian and ensure they are responsible for managing data quality

- develop and maintain a data quality management plan for each critical dataset

- create a data quality statement for each critical dataset and publicly release it

- assess their data systems by checking:

- if the data is accurate and valid, and to what level

- how complete the data is and if there are there known gaps

- if the dataset represents the conditions or scenario that it refers to

- if the timeliness and age of the data is appropriate for its purpose

- what collection methods they use and if they are consistent.

The Data Quality Standard is part of the government’s Information Management Framework for the Victorian Public Service.

When it implemented this framework in 2018, the government said:

'By 2020, the Victorian government and its citizens will have access to trusted information that improves decision making, enables insight and supports the planning and delivery of good policy and better services to the public'.

The government expected agencies to be fully compliant by 2020.

Victorian Government’s Data Quality Guideline

The Data Quality Guideline Information Management Framework (Data Quality Guideline) gives further guidance and information on the Data Quality Standard’s minimum requirements.

It also outlines 7 data quality dimensions, which Figure 1C shows.

FIGURE 1C: Data quality dimensions

Source: VAGO, based on the Data Quality Guideline.

Data controls

Data controls help organisations protect the quality of their data. Some examples of data controls are:

- completeness checks, which ensure records are processed from initiation to completion

- validity checks to ensure only valid data is recorded or processed

- identification controls to ensure unique identification of all users

- authentication to verify the identity of users attempting to access data

- input controls to ensure data integrity (for example, not putting text in a numeric field)

- forensic controls to ensure data makes sense (for example, checking the end date is after the start date).

The Data Quality Guideline states that departments’ data systems should have:

- appropriate data entry controls, such as field validation, length and type restrictions, and reference lists to make sure users enter complete data

- where possible, automated validation processes to make sure data is accurate.

Information privacy principles

The Victorian Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 sets minimum standards for how Victorian public sector organisations must manage personal information.

In relation to data quality, it says that ‘an organisation must take reasonable steps to make sure that the personal information it collects, uses or discloses is accurate, complete and up to date’.

1.4 Existing data quality issues

When we analysed CRIS data for our June 2022 Kinship Care audit, we found that data was not always up to date or accurate.

Other reviews have found similar issues with child protection data. Figure 1D lists some of these reviews.

FIGURE 1D: Previous reviews about child protection data quality

| Review | Year | Data quality issues raised |

|---|---|---|

|

Victorian Ombudsman’s Own motion investigation into the Department of Human Services Child Protection Program |

2009 |

The report raised significant concerns about CRIS’s adequacy and its ability to meet the child protection system’s needs. |

|

Royal Commission into Family Violence |

2016 |

The royal commission identified limitations with the child protection system’s ability to share relevant information with the family violence and broader human services system. This is partly because these sectors rely on outdated information technology (IT) systems. |

|

Commission for Children and Young People’s Out of sight: Systemic inquiry into children who are absent or missing from residential care |

2021 |

The report found that information that may be critical to completing risk assessments is ‘often buried in generic document types or free-text fields in data systems with limited search capacity’. |

|

Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner’s Unauthorised access to client information held in the CRISSP database |

2021 |

The report found that a former employee of an external service provider DFFH contracted to deliver child protection services gained unauthorised access to CRISSP after their employment ended. This led to 260 data breaches over the course of a year. The report found that both DFFH and the contracted service provider breached information privacy principles. |

|

Commission for Children and Young People’s Our youth, our way: Inquiry into the over representation of Aboriginal children and young people in the Victorian youth justice system |

2021 |

The report found that critical data about the ‘crossover’ cohort of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people who are involved in both the youth justice system and child protection system was not readily available through CRIS. |

Source: VAGO.

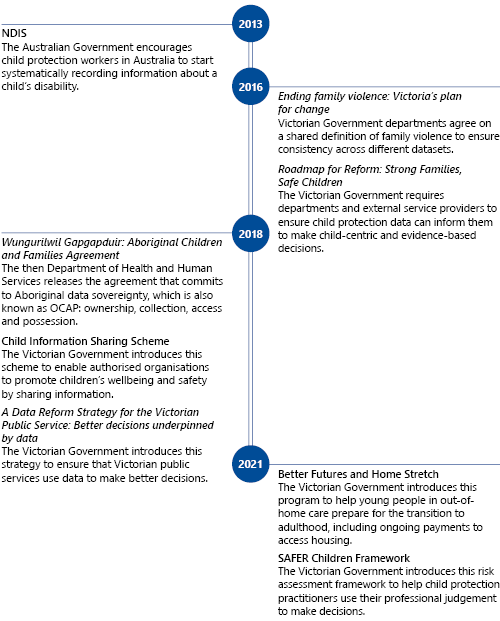

1.5 Relevant sector reforms

Sector reforms have shaped the way that child protection data should be collected, stored and shared in Australia.

For example, the Victorian Government introduced the Child Information Sharing Scheme in 2018 in response to the Royal Commission into Family Violence.

Figure 1E shows relevant sector reforms and how they have affected child protection data.

FIGURE 1E: Timeline of relevant sector reforms

Source: VAGO.

2. Quality of child protection data

Conclusion

We reviewed CRIS data and found multiple instances of incomplete, inaccurate and inconsistent information.

This means that DFFH’s child protection data does not readily provide current and complete information on vulnerable Victorian children.

This also limits DFFH’s ability to make informed decisions that are in the best interests of vulnerable children.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Incomplete data

We found many CRIS files with missing or incomplete information, including incomplete:

- personal details

- court details

- information about children's development needs.

DFFH told us that this is partly because users often record data in case notes, which are free-text fields. It told us users do this because it is easier than using CRIS’s specific searchable fields.

CRIS does not have a search function to find information in case notes. This means that users need to go through a significant amount of free text in case notes to find the information they are looking for.

As the Commission for Children and Young People reported in Out of sight: Systemic inquiry into children who are absent or missing from residential care, information that may be critical to completing risk assessments is ‘often buried in generic document types or free-text fields in data systems with limited search capacity’.

Incomplete personal details

It is important that personal information in CRIS is complete and up to date.

DFFH staff told us that they use this information to tell children who have the same names apart, particularly if users have recorded them differently in different systems.

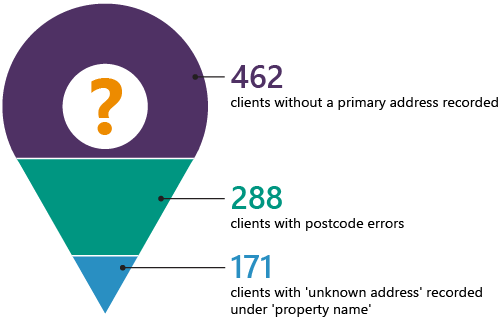

Figure 2A shows that we found incomplete personal details, such as missing addresses, in the 18,717 cases recorded as of 25 May 2022.

DFFH told us that information can sometimes be incomplete because it is still gathering it, such as during early stages of investigation.

FIGURE 2A: Incomplete personal details we found in CRIS

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data. This data excludes cases at the intake phase.

Incomplete court details

Child protection practitioners occasionally need to get the Children’s Court to make decisions about a child’s welfare, such as who they are allowed to have contact with.

When this happens, child protection practitioners must record the outcome in CRIS on the same day of the court event. This is to make sure that other staff who need to look at the child’s file can access this critical information.

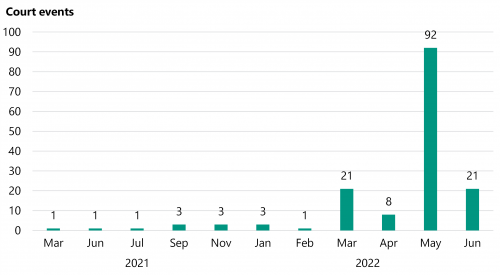

However, our review of DFFH's Children’s Court events as of 2 June 2022 found that 155 court activities (26.8 per cent of the total client files with relevant court activities) had not been updated in CRIS.

The earliest unrecorded court event dated back to 16 March 2021, which was more than 16 months before our review.

Figure 2B shows the court events by month that did not have an outcome recorded in CRIS.

FIGURE 2B: Court events before 2 June 2022 with no recorded outcome in CRIS

Note: These court events do not have an outcome populated in CRIS’s court summary field. However, users could have recorded court outcomes elsewhere in CRIS, such as in a case note.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Not recording court outcomes on time creates the risk that DFFH might arrange for a child to visit a family member that a court order does not allow contact with.

Figure 2C provides an example of this risk.

FIGURE 2C: Case study: 3-month delay to update a court outcome in CRIS

A family reunification order means the Children’s Court has ruled that a child needs protection. Under a reunification order, a child cannot safely stay in their parents’ care while the safety concerns are being addressed. This makes DFFH responsible to place the child in out-of-home care, with the ultimate objective to reunify them with their parents when it is safe.

DFFH made another application in January 2022 to add 2 conditions to the order:

- Both parents agree to random drug tests.

- The parents may have unsupervised contact with the child for at least 2 nights a week.

On 25 January 2022, the court extended the family reunification order to 25 July 2022. However, nothing in CRIS―either in case notes or the court summary field―mentioned this outcome until 3 weeks after the January court order.

The court made a further decision on 8 March 2022 about the order’s details. However, this was not updated in CRIS until 8 June 2022, which was 3 months later. The CRIS file also shows that the child did not have an allocated child protection practitioner for almost 2 months during this time.

Not updating the court outcome in CRIS meant that DFFH staff could not check the child’s current contact arrangements. This creates the risk that contrary to the child’s best interests, they could have been having contact that the current court order did not allow. In this case, this risk was increased because no staff were allocated to the child for 2 months.

Source: VAGO, based on a CRIS file.

DFFH told us it will consider how it could better support child protection practitioners to record all court activity in a timely way by refreshing its child protection procedure documents.

Incomplete information about children's development needs

DFFH must record critical information about each child in out-of-home care under CRIS’s 7 ‘looking after children’ domains. These domains are:

- health

- emotional and behavioural development

- education

- family and social relationships

- identity

- social presentation

- self-care skills.

For example, in the health field staff must record:

- the child’s Medicare number

- their general practitioner’s name and contact details

- if they have a disability or complex medical need and associated NDIS plan

- a record of any immunisations they have had.

It is crucial that DFFH can track children’s health, wellbeing and development to deliver its child protection services.

However, our data analysis found that staff do not always complete this required information.

Figure 2D shows some of the gaps we found in children's health and personal information.

These gaps create considerable risks. For example, for 19 per cent of current CRIS files, staff cannot easily access information about a child’s disability or related treatment needs without searching through case notes.

This also means that DFFH cannot consistently report on the issues that affect children with a disability in out-of-home care.

DFFH told us that it started requiring staff to record a child's disability status and complex medical needs in 2018. However, it did not apply this requirement retrospectively. Therefore, cases that existed before this change would need to be updated on a case-by-case basis.

FIGURE 2D: Data gaps we found in children's health and personal information

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

2.2 Inconsistent data

Child protection data in CRIS feeds into DFFH’s other information management systems, including its carer payment system.

Inconsistent data can be inefficient for DFFH staff to manage.

For example, staff may need to enter it twice in different systems.

It can also cause confusion about which dataset has the most complete information.

If a child is in an unstable placement or moves between many placements it can negatively affect their development.

As a result, policymakers and child protection practitioners need access to consistent, current and accurate information to monitor how children move through the child protection system.

Inconsistencies between CRIS and DFFH’s carer payment system

DFFH uses its carer payment system to pay carer allowances. It calculates these payments based on each child’s placement type, for example, foster care or kinship care.

Respite care gives the kinship or foster carer a break from caring. It is usually an ongoing arrangement where the child spends short, regular periods of time with another carer.

DFFH told us that a child can only be in one placement at once unless they have a respite care arrangement.

This means that ideally, the number of placements recorded in CRIS and DFFH’s carer payment system should be the same. However, this is not the case. We found inconsistencies between the number of children in placements across both datasets.

Limitations in DFFH's procedures in recording children's placement data in both datasets mean that it is difficult to determine the extent of the discrepancy.

DFFH acknowledges there are inconsistencies and advised us that its analysis points to up to 437 more children placements recorded in its carer payment system compared to CRIS.

The discrepancies between CRIS data and its carer payment system suggest that DFFH has poor end-to-end visibility of children in out-of-home care placements and carer payments. This creates the risk that DFFH:

- cannot confirm where children it is responsible for are being cared for

- may be paying carers who do not have children in their care

- may delay paying carers.

DFFH told us that the higher number of placements in its carer payment system is due to:

- a legacy issue where staff could previously set up carer payments without a corresponding court order or placement recorded in CRIS

- the carer payment system recording placements for young people over the age of 18 who are technically not in the child protection system anymore, but their carer can still receive a carer's allowance. For example, a carer might get an allowance to continue providing a home to support a young person over 18 who is still doing secondary education

- delays in external caseworkers updating placement details in CRIS. However, DFFH told us that senior child protection practitioners (team leaders and above) can update placement data in CRIS if external caseworkers have not done it in a timely way.

DFFH told us that it has not tried to reconcile the differences between the 2 datasets because it involves manually matching individual placement entries, which requires specific technical knowledge about the child protection process.

DFFH also told us that it does not have the resources to do this time-consuming manual task.

Legacy issue

DFFH told us that the legacy issue where staff could previously set up carer payments without a corresponding court order or placement recorded in CRIS will gradually reduce because:

- DFFH has progressively strengthened its processes and systems, including:

- initially by requiring staff to include court orders and placement information in its carer payment system

- later by requiring staff to trigger payments from CRIS

- the children recorded in the carer payment system will age and exit the child protection system when they turn 18.

DFFH told us that it will reconcile information across the 2 systems to ensure that they are correctly recorded. It is also working on better aligning the 2 systems and plans to finish this work in March 2023.

2.3 Inaccurate data

In this context, an incident is an event or circumstance where a child in out-of-home care is harmed or could have been harmed.

When we analysed CRIS data, we found many instances where incidents or education details were recorded inaccurately.

Education details

While DFFH has a data quality control to make sure child protection practitioners update education details regularly, we found that this is not working as intended and files are not being updated as required.

For example, we found 261 instances where a child’s education end date was before the start date.

In another case, a child’s CRIS file said they had been enrolled in their first year of school for over 10 years.

This means that DFFH may not have an accurate understanding of children's education statuses.

Incidents

Child protection practitioners and external caseworkers record incidents involving children in out-of-home care in CIMS.

They must create a new report for each new incident.

DFFH advised that they can create incident reports directly in CIMS or by way of another IT system, which populates the information into CIMS.

If DFFH does not correctly match an incident report in CIMS to a CRIS file, there is a risk that the child’s caseworker or child protection practitioner and carer may not know about it and give them the support they need.

DFFH staff use a range of unique identifiers to match incident reports with CRIS files, such as a child’s name, date of birth or address.

If these details are incorrect in the CIMS report, there is a risk that staff will either not be able to link an incident report to the child’s CRIS file or will incorrectly link it to another child’s file.

Further, if a child's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status is recorded incorrectly in CIMS, it can affect DFFH's decisions about them.

While each CRIS file has a unique identification number, or ID, DFFH does not require child protection practitioners and external caseworkers to record this in incident reports. This is because service providers sometimes use an alternative IT system to record incident reports.

Between 1 May 2021 and 1 May 2022, DFFH could not match 72 incident reports to a CRIS file. This could be for a number of reasons, including that:

- it could not find a corresponding child in CRIS

- the child's case was no longer active

- the incident was already manually recorded on the file.

As Figure 2E shows, we also found incident reports that had incomplete and inconsistent data.

FIGURE 2E: Inconsistencies in incident reports on CIMS

| Field | Data quality issue |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Date of birth |

|

| Address |

|

| CRIS ID |

|

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Figure 2F gives an example of a young person whose incident reports had inaccurate details.

FIGURE 2F: Young person recorded in CIMS with inaccurate details

Most of these reports related to ‘dangerous actions’. Across these incident reports, we found significant data errors and inconsistencies, including:

- one report had an incorrect date of birth

- 5 reports listed an incorrect gender

- 3 reports had an incorrect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status.

We also found another incident report about the same young person that recorded their name incorrectly.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

3. Factors affecting data quality

Conclusion

The factors that contribute to DFFH’s poor-quality child protection data include:

- DFFH does not comply with the Data Quality Standard

- CRIS is not fit for its intended purpose and its data quality controls do not always work

- child protection practitioners and caseworkers do not have time to record information in a timely way due to their heavy workload.

DFFH told us that it is aware of these issues and is working on a plan to address them.

But without adequate resourcing, there is a high risk that DFFH will not be able to effectively address them.

As a result, DFFH will continue to make decisions based on poor quality data.

This chapter discusses:

3.1 Noncompliance with the Data Quality Standard

The Data Quality Standard requires government departments ‘at a minimum’ to:

- assess critical datasets, like child protection data, against the data quality dimensions to make sure they are fit for purpose

- have a data quality statement that outlines known data quality issues

- develop a data quality management plan to address data quality issues

- have accountable officers to manage data quality.

However, we found that DFFH does not comply with these minimum requirements.

Not assessing child protection data against quality dimensions

The Data Quality Standard took effect in 2018. The government expected agencies to have compliant datasets by 2020.

However, DFFH did not meet this timeline and had not assessed its child protection data against the data quality dimensions.

By not doing this, DFFH could not:

- easily identify strengths, weaknesses and improvement areas within its child protection dataset

- prioritise areas for improvement

- effectively manage risks that come from poor-quality data

- effectively allocate resources to data quality improvement initiatives.

This also means that DFFH could not develop a data quality statement and management plan.

DFFH told us that it started assessing its child protection data against 8 quality dimensions in June 2022―after we started this audit. It says that these 8 dimensions suit its requirements better than the Data Quality Guideline's 7 dimensions.

No data quality statement

A data quality statement summarises a dataset's main characteristics, including known and potential data quality issues.

According to the Data Quality Guideline, if a department is missing a data quality statement then it cannot advise users if the data is fit for its intended purpose.

DFFH told us that it has started working on a data quality statement for its child protection data and expects to complete it in September 2022.

No data quality management plan

A data quality management plan should:

- include ways to resolve identified data quality issues

- track improvements

- monitor and identify new data quality issues.

According to the Data Quality Guideline, if a department is missing a data management plan, then it cannot systematically plan to identify new data quality issues, address known issues and monitor and report on improvements over time.

DFFH advised us that it is working on a data management plan for its child protection data and expects to complete it in September 2022.

Unclear data quality management responsibilities

DFFH has identified key staff as the steward, custodian and administrator of its child protection data. These staff have a shared role in managing data quality.

However, DFFH has not clearly articulated how these officers are meant to work together to do this role.

DFFH told us that the steward and custodian are responsible for data quality. While they can delegate tasks to other staff members on a day-to-day basis, this does not remove their responsibility to make sure other staff carry out these tasks.

DFFH’s noncompliance with the Data Quality Standard’s minimum requirements means that its accountable officers have not effectively performed their data quality management responsibilities.

DFFH told us that since this audit started, it has clarified its accountable officers' responsibilities. The data custodian is now responsible for managing data quality.

It has scheduled quarterly meetings between the data custodian and the chief data officer to ensure they oversee data quality and monitor progress on the data quality management plan.

3.2 Ineffective controls

Our review of DFFH's child protection data and CRIS’s design, business processes and current validation and quality controls found that CRIS is not fit for its intended purpose.

CRIS is a legacy system that has not kept pace with technology and sector changes.

For example, unlike modern systems and applications, CRIS does not integrate with DFFH’s other important systems, such as its carer payment system.

We have sighted documentation seeking government funding for DFFH's technology reform for its data systems, including for its child protection data.

We assessed the effectiveness of 22 CRIS data quality controls.

We selected these controls based on their:

- risk

- materiality, or the significance of the particular data it refers to

- relevance to data quality gaps other agencies have identified.

While some controls were designed effectively, 19 out of 22 were not implemented effectively and do not help either to prevent or identify data quality issues.

In particular, CRIS has:

- weak data validation controls

- weak user access controls

- data quality assurance processes, but these are not a substitute for high-quality data

- no data dictionary.

DFFH staff also have limited access to training and guidance about data quality controls.

Weak data validation controls

Data validation controls make sure users enter data accurately and completely. For example, a system could have data validation controls that:

- check mandatory or required fields have an entry

- check entries are in the right format, such as a date, number or specific sequence

- do custom forensic checks, such as making sure a child’s primary school completion date is after the recorded start date.

CRIS has data entry controls for many of its fields. For example:

- it checks data is a standard format, such as a date, or limits it to a specific set of options. Examples include:

- a drop-down list of placement types staff must enter data in specific fields to complete a record or workflow

- staff need to enter data in the SAFER probability harm judgement text field to complete an intake risk assessment record

- it has date controls based on legislation or other process requirements. For example, staff cannot enter a court order expiry date that is longer than the maximum period that the law allows.

However, we found that some entry controls are either not working or not in place for some important data fields. This compromises the entire dataset’s quality and reliability.

For example:

|

The field to record … |

Does not … |

This means … |

|---|---|---|

|

criminal record checks for carers and household contacts, which is mandatory for kinship care assessments |

stop child protection practitioners from completing the assessment if it is not filled. |

DFFH does not always have the minimum information it needs to assess the safety of a kinship placement. For example, in our Kinship Care audit we found instances of kinship care assessments with no criminal record check. |

|

Victorian Working with Children Check numbers, which is a free-text field |

require users to enter data in a specific format, even though Victorian Working with Children Check numbers usually have a specific combination of letters and numbers. |

DFFH cannot easily verify that all carers have a valid Victorian Working with Children Check. For example, we found some files where this field had entries such as ‘overseas carer’, ‘closed case’ or invalid number sequences. |

|

Looking-after-children information (including education and disability data) |

have prompts to make sure that staff regularly update this information. While it is not a mandatory field, DFFH’s Child Protection Manual requires staff to update it at least every 6 months |

DFFH cannot confirm that it consistently monitors the social and wellbeing needs of children in out of home care. |

Weak user access controls

As the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner’s Unauthorised access to client information held in the CRISSP database report found, having strong user access controls for child protection data is important 'given the nature of the information stored in CRISSP and the vulnerability of the people it is about'.

DFFH told us it does not have a procedure to regularly make sure that only authorised users can access CRIS.

DFFH explained to us that it onboards and off-boards CRIS users as part of its employment process.

It also reviews a staff member's CRIS access if they are involved in a disciplinary or misconduct proceeding.

To deactivate a user’s access, staff must raise a specific deactivation request with one of DFFH's systems administration teams.

Once the request is received, the ICCMS systems administration team processes it.

DFFH told us that it also deactivates internal CRIS users after 60 days of inactivity.

It does this by sending an email to the user that gives them 2 weeks to log into CRIS if they still need access.

If they do not log into CRIS, DFFH automatically deactivates their access.

However, data DFFH gave us suggests that there were at least 63 active CRIS accounts after the 60-day deactivation process should have removed their access. Figure 3A shows this.

FIGURE 3A: Number of days between users’ last login dates and 23 June 2022

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

If the deactivation process does not work as intended, then staff who are no longer authorised to log into CRIS may still be able to access sensitive information and enter data.

This could affect the dataset’s accuracy and reliability.

Other elements of DFFH decision-making processes are insufficient

DFFH told us that CRIS is one of many tools it uses to make sure its child protection decisions are sound and align with its responsibilities under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005.

However, its other tools and processes are not a substitute for high-quality data. For example:

|

DFFH told us it … |

But |

|---|---|

|

relies on other sources of information, such as the Child Protection Manual, practice frameworks and guidance, and professional judgement |

there is a risk that child protection practitioners may not always have enough time to take advantage of them. |

|

has processes where team managers must endorse child protection practitioners’ decisions at certain stages of the child protection process |

there is a risk that inaccurate or incomplete data may misinform supervisors’ decisions at these critical decision points. |

|

requires child protection practitioners to have one to 2 hours of supervision discussions per fortnight to discuss decisions |

this only happened 58 per cent of the time in 2020–21. |

No data dictionary

A data dictionary helps users understand the purpose of each field in a data system and how they should fill them.

They are essential because they help departments maintain the integrity of their data, particularly in workplaces with high staff turnover.

CRIS has ‘help’ functions and some data validation controls, but DFFH does not currently have a data dictionary that identifies the full set of fields and lists their corresponding definitions.

Not using fields correctly

Without a data dictionary, child protection practitioners may continue to incorrectly enter information and develop their own understanding of what fields are for.

For example, we found a number of instances where child protection practitioners used the citizenship field to enter information about a child’s birth certificate.

Sometimes an out-of-home care placement breaks down. If this happens, the child protection practitioner should record 'unplanned exit, caregiver withdrew' in CRIS’s ‘reason placement ended’ field.

![]() This is significant for the kids and doesn't tell the full story.'

This is significant for the kids and doesn't tell the full story.'

However, we heard from a child protection practitioner that some users record ‘planned exit’ in this field when a placement broke down if they arranged another placement for the child.

This means the recorded information does not accurately show that the child went through a placement that did not work and may therefore need support or special needs that should be considered for future placements.

Limited access to training and guidance

CRIS is a complex case management system.

Ongoing and accessible training, guidance and support is important to make sure users enter information consistently and in line with DFFH’s expectations.

Training

DFFH runs limited ongoing CRIS and CRISSP training for child protection practitioners and external caseworkers.

For child protection practitioners, DFFH’s CRIS-specific training is currently limited to:

- an introductory course for new starters

- how to complete and record risk assessments under the SAFER Children Framework Guide

- a self-learning tool where staff can practise using CRIS by entering data in a learning environment.

DFFH has not run mandatory CRIS training courses on its court and case practices due to COVID-19. To address this gap, DFFH has provided other types of support to address these gaps. For example, it:

- publishes training videos

- runs fortnightly practice discussions

- has set up a court practice advice and support service.

However, these supports do not specifically train staff on how to use CRIS for these practice areas.

This is an issue because court and case practice are fundamental aspects of child protection practitioners’ work.

DFFH told us that these supports would have used CRIS to demonstrate how practitioners should record information and decisions in the system.

DFFH has not run CRISSP training for external caseworkers due to COVID-19.

DFFH’s child protection team managers and staff, including informal ‘CRIS champions’, are responsible for providing ongoing training and support to other staff.

This arrangement can help staff build interpersonal relationships and get help to quickly complete tasks on CRIS.

However, there are also potential issues because:

- supervisors may not have the capacity to adequately train staff due to their high workload

- there is a risk that staff may have inconsistent approaches to training and guidance, which could make others learn practices and habits that are inconsistent with DFFH’s expectations.

DFFH told us that there are other ways for staff to get training and support through its office of professional practice unit and CRIS help desk.

DFFH also told us that it now has access to facilities to run face-to-face training again.

Guidance

DFFH has an extensive range of guidance material for child protection practitioners and external caseworkers.

However, this guidance is not in a central location. Instead, it is spread across:

- its internal intranet, or intranet for service providers

- CRIS or CRISSP.

This means that users cannot easily access the full set of guidance because they need to search across 2 platforms.

DFFH acknowledges that consolidating its guidance material in one spot would help it make sure it is up to date and accessible. It told us that it is working on this.

DFFH told us that it informs child protection practitioners about changes to the Child Protection Manual, including practice changes to recording information in CRIS, with automated emails.

3.3 Workload issues

![]() Definitely workload. Number one. Sometimes staff go from one job to another. Have insane weeks, where only the week after can we update admin. Have been lots of new recruits and now have got more new than experienced staff. So a lot of support rely on experienced people. But then the experienced staff don’t have time to update their own CRIS pages. System is only as good as people can update.'

Definitely workload. Number one. Sometimes staff go from one job to another. Have insane weeks, where only the week after can we update admin. Have been lots of new recruits and now have got more new than experienced staff. So a lot of support rely on experienced people. But then the experienced staff don’t have time to update their own CRIS pages. System is only as good as people can update.'

Nationally, the demand for child protection services has steadily increased over the last 5 years. This has put immense pressure on child protection practitioners.

Child protection practitioners we interviewed told us that they cannot prioritise updating child protection data due to competing priorities and workload issues.

These staff said that this is particularly true for regularly updating information in CRIS.

For example, one staff member told us that ‘the quantity of data that needs to be entered and reported outweighs the hours to complete the work’.

DFFH acknowledges that when staff have heavy workloads, they might not be able to record information in CRIS in a timely way. It also recognises that this can reduce the quality of the data. Child protection practitioners’ heavy workloads are mainly caused by:

- high case loads

- needing to do additional work on cases awaiting allocation

- workforce recruitment and retention issues.

High case loads

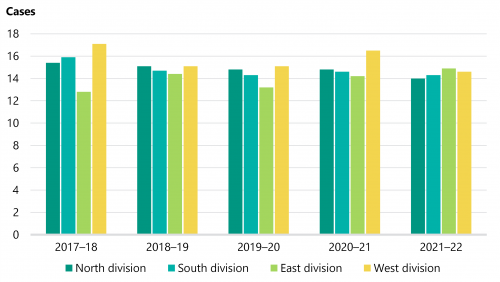

As Figure 3B shows, DFFH’s data suggests that on average, a child protection practitioner has a median case load of 15 cases that involve vulnerable children and their families.

A case’s complexity determines how much time the child protection practitioner needs to update it. For example, cases involving protection applications to the Children’s Court can require a lot of administrative work.

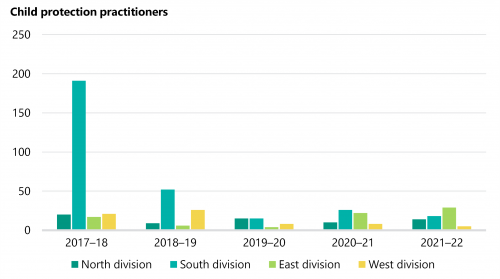

FIGURE 3B: Median allocated case loads for child protection practitioners by DFFH division from 2017 to 2022

Note: 2017–18 is from 1 May 2017 to 30 June 2018. 2021–22 is from 1 July 2021 to 2 May 2022. All other financial years are from July to June.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

However, as Figure 3C shows, there are many child protection practitioners who manage more than 25 cases each.

FIGURE 3C: Number of child protection practitioners with 25 allocated cases or more by DFFH division from 2017 to 2022

Note: 2017–18 is from 1 May 2017 to 30 June 2018. 2021–22 is from 1 July 2021 to 2 May 2022. All other financial years are from July to June.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Cases awaiting allocation

Child protection practitioners we interviewed said that tasks for cases awaiting allocation further increase their workload.

Data DFFH gave us suggests that at 25 May 2022, 3,130 children in the child protection system did not have an allocated child protection practitioner (excluding children whose cases were at the intake stage or awaiting allocation for less than 4 days).

DFFH’s child protection procedures say that team managers are responsible for working on cases awaiting allocation, including updating CRIS.

We heard from team managers that this usually involves monitoring cases on the awaiting allocation list and delegating urgent tasks when they arise.

Some divisions referred to a ‘duty roster system’ where team managers use a roster to delegate tasks.

However, if a child has multiple child protection practitioners looking after them, it may reduce the consistency and completeness of their CRIS file.

Workforce recruitment and retention

High staff turnover may contribute to poor-quality data because:

-

there are less experienced staff to train and mentor junior staff

- CRIS is a legacy system, so more-experienced staff have a significant amount of information about CRIS 'workarounds' that may be lost if they leave.

In January 2022, the staff turnover rate for all child protection practitioner positions was 19 per cent.

The Victorian Government has invested a significant amount of funding to recruit more child protection practitioners.

However, as Figure 3D shows, DFFH is struggling to fill these positions.

DFFH told us that it has a targeted recruitment campaign underway to recruit more staff.

However, it said there is a significant shortage of workers across the social services sector at an international level.

This has affected its ability to recruit the number of child protection practitioners it needs to meet demand.

FIGURE 3D: Differences between DFFH’s child protection workforce numbers and child protection operating model targets from 2017 to 2022

| Difference between actual child protection workforce and targets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial year | Actual child protection workforce* | Child protection operating model targets | Number | Percentage |

| 2017–18 | 1,932.7 | 1,944.8 | −12.1 | −0.6% |

| 2018–19 | 2,107.1 | 1,956.8 | 150.3 | 7.4% |

| 2019–20 | 2,047.5 | 2,001.1 | 46.4 | 2.3% |

| 2020–21 | 2,121.1 | 2,240.1 | −119 | −5.5% |

| 2021–22 | 2,183.3 | 2,486.1 | −304.8 | −13.1% |

Note: *This includes ongoing, fixed-term and casual staff. 2021–22 data is from 1 July 2021 to 2 May 2022. The last column represents percentage difference rather than percentage change. Percentage difference = (absolute difference ÷ average) × 100.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

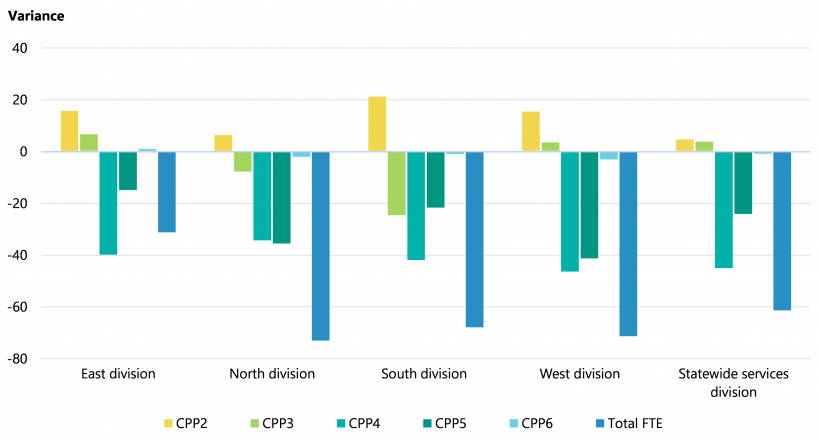

As Figure 3E shows, the workforce’s proportion of senior and more-experienced staff in 2021–22 was below the target in almost all of DFFH’s divisions.

For example, during the 2021–22 financial year, DFFH was short by:

- 137.2 child protection practitioners at the child protection practitioner 5 level

- 207.3 child protection practitioners at the child protection practitioner 4 level

The complexities and challenges of a legacy system like CRIS increase the chance of data quality issues because:

- of organisational memory loss

- there are fewer experienced staff available to mentor and train new staff.

FIGURE 3E: Child protection practitioner staff in 2021–22 by level compared to the target number of positions

Note: CPP stands for child protection practitioner. FTE stands for full-time equivalent.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Appendix A. Submissions and comments

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix A. Submissions and comments.

Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary.

Click here to download Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

Appendix C. Scope of this audit

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix C. Scope of this audit.

Appendix D. DFFH’s ICCMS structure and links

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix D. DFFH’s ICCMS structure and links.

Click here to download Appendix D. DFFH’s ICCMS structure and links