Additional School Costs for Families

Overview

Parent payments have become essential to the provision of free instruction in government schools. In 2013–14, Victorian government schools received

$626 million from parents and other locally generated funds.

While schools are autonomous and responsible for managing their own parent payment practices, the Department of Education and Training (DET) is responsible for supporting and guiding them. DET provides policy and guidance material designed to assist schools in achieving compliance and better practice but parts are confusing and many schools are not following them.

Under the devolved school model, there is a need for sound governance arrangements. However, DET does not oversee school compliance with the law and policy and has no oversight on what items and how much schools charge parents. Schools are consequently charging parents for items that should be free.

School principals point to the inadequacy of school funding as the cause of rising parent payments. DET does not know how much it costs to run a school and its funding model distributes money based on relative need, rather than actual need. DET is therefore poorly positioned to shape government funding decisions.

Appendix A. Victorian school funding explained information piece explains where the funding for education comes from and what it is used for.

Additional School Costs for Families: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2015

PP No 3, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit the Auditor-General's report on the audit Additional School Costs for Families.

The audit assessed whether the Department of Education and Training (DET) and government schools are managing parent education costs economically, efficiently and effectively and in accordance with legislation and policies.

The audit found that parents payments vary significantly from school to school and in some cases, parents are being charged for items that should be free. While parent payments have become critical to the operation of government schools, DET has little understanding of what an efficient and economical school looks like. It is therefore poorly positioned to shape decisions made by the Commonwealth and state governments about funding for schools.

As part of this audit, I have also produced a Victorian school funding explained information piece. This is a critical piece of work that exposes school funding arrangements to public scrutiny for the first time in Victoria. I hope that this will help to inform public policy debates around school funding and will assist parents to understand how schools are funded and to ask critical questions of their schools about how their funds are used.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

11 February 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Kristopher Waring —Engagement Leader Kyley Daykin—Team Leader Shelly Chua—Analyst Ryan Ackland—Analyst Alainnah Calabro—Graduate Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Dallas Mischkulnig |

The principles of free, secular and compulsory education were first established in Victoria in the Education Act 1872. However, these provisions have been watered down over time. Parents of children in government schools are now required under law and government policy to pay for items such as books, stationery and camps.

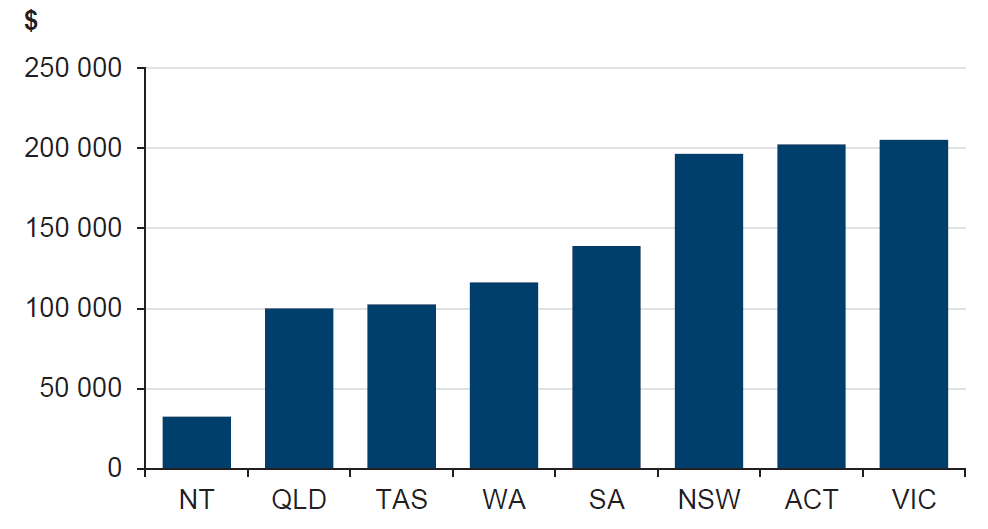

Each year parents are being asked to pay more. In 2013, they paid $310 million to schools—$558 per student—a rise of $70 million or 29 per cent since 2009. In addition to school parent payments, parents are also expected to buy school uniforms, gym clothes, shoes and other essential items, adding significantly to the cost of a child's education.

In Victoria, government schools are largely autonomous, and each school council can determine how much to request from parents. The amounts charged to parents vary significantly from school to school with minimal oversight from the Department of Education and Training (DET). Although DET has developed a parent payment policy and supporting guidance for schools, it takes no responsibility for monitoring and enforcing school compliance with these. This means there are no consequences for schools that charge parents for items that should be provided for free.

School principals have pointed to the inadequacy of school funding as the main reason for increasing parent payments. While there is some evidence to support this claim, DET has done little to find out what it actually costs to educate a child. Without this information it cannot inform government about whether the funding it provides is in fact adequate, or that it is being used efficiently, effectively and economically by schools.

DET's school funding model is complex. It combines many sources of funding and attempts to address areas of need and priority. As a result, it is almost impossible for a parent, Parliamentarian, or the public to understand how much money schools get, where the money comes from and how it should be used.

To help clarify school funding, I prepared a Victorian school funding explained information piece to accompany this report. It deconstructs DET's funding model and shows how money reaches government schools from various sources.

In developing this information piece it has become clear to me that government schools actually control very little of the available funding. More than 80 per cent of school funds are tied up in teacher salaries. This means that, despite having autonomy to make localised decisions about how best to run their school, they receive limited direct funding to help them do so.

However, what I found most concerning is that schools generate almost as much income themselves—$626 million in 2013–14—as they receive in cash payments from DET—$771 million in 2013–14. This clearly demonstrates just how critical parent payments and other locally-generated funds have become to the ongoing viability of government schools.

There is a serious lack of transparency surrounding parent payments and school funding in Victoria and DET has failed to ensure that it has the necessary checks and balances in place to oversee school practices. Over time, parent payments have evolved from being used to support free instruction, to being essential to its provision.

I have made a series of recommendations in this report which, if actioned, will improve school compliance with DET's parent payment policy and legislation, and lead to greater transparency for parents. I have also recommended that DET seek to better understand the funding needs of schools to improve its capacity to advise government on school funding.

I am pleased that DET has accepted all of my recommendations, and I am further encouraged by the work that has already taken place to resolve some of the issues identified in this audit.

I would like to thank the schools that were surveyed by my audit team and DET staff who provided evidence required for this audit report and the attached Victorian school funding explained information piece which I hope will provide a template for improved transparency around school funding into the future.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

February 2015

Audit Summary

In Victoria, the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (the Act) requires parents to enrol children aged six to 17 years in a registered school, or to register for home schooling.

The Act requires the government to deliver free instruction in the standard curriculum program to all students under the age of 20 years. The standard curriculum program is made up of eight key learning areas—the arts, English, health and physical education, languages other than English, mathematics, science, studies of society and environment, and technology. Government schools receive funding from both the Commonwealth and state governments to do so. The Department of Education and Training (DET) administers these funds through the school budget—known as the Student Resource Package (SRP). In 2013–14, government schools received $5.5 billion from the Commonwealth and state governments.

However, this does not mean that it is, or should be, free to attend a government school. The Act permits school councils to charge parents fees to cover costs for goods, services or other things provided to a student that are not directly related to the provision of free instruction. They may also raise additional funds through voluntary financial contributions from parents. However, in doing so, schools have to delicately balance their need for additional funding with the imposition that additional costs pose to families and their ability to meet those costs.

DET's current parent payment model allows each school council to determine its own parent payment policies and procedures within a set of parameters outlined in DET's parent payment policy. It is the role of principals to ensure the school‑level policy complies with DET's parent payment policy. However, DET does not monitor and enforce compliance and there are no consequences for schools who do not comply.

The audit objective was to assess whether DET and government schools are managing parent education costs economically, efficiently and effectively and in accordance with legislation and policies. It examined funding for the delivery of free instruction, departmental oversight of school approaches to parent payments and parent payment policies and practices.

This audit was commenced under the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). On 1 January 2015, machinery of government changes took effect and the responsibilities of the former DEECD transferred to DET.

Conclusions

Over time, parent payments have evolved from being used to support free instruction, to being essential to its provision. In effect, parents are being charged for items and activities that should be free under legislation and policy.

School principals point to the inadequacy of school funding as the cause. However, DET does not have a clear understanding of what an efficient and economical school looks like. In the absence of this fundamental information, it does not know whether school funding is or is not adequate. Without this information, it is poorly positioned to shape decisions made by both the Commonwealth and the Victorian Government about funding for schools.

Schools also request parent payments to run programs that reflect the aspirations of the school community—such as superior music programs and overseas trips. It is reasonable for schools to provide these optional programs on a user-pays basis in line with school community demand. However, parent payment requests are not sufficiently itemised by schools and consequently it is not clear to parents what they must pay for and what they can choose to pay. There is a need for greater transparency in how parent payments are requested by schools.

Despite having a devolved accountability system, there remains a need for sound governance arrangements and appropriate support and guidance. There must also be suitable checks and balances in place to keep schools accountable.

The findings of this audit show that DET has shifted responsibility onto school principals and councils without ensuring that the required checks and balances are in place and are effective. This is a fundamental failure in DET's internal controls.

Findings

School funding for free instruction

Parts of DET's parent payment policy are vague and not sufficiently prescriptive. Consequently, there is no shared understanding between DET and schools on the definition of free instruction in the standard curriculum or on the main elements of the three parent payment categories—essential education items, optional extras and voluntary financial contributions.

Despite one of the key principles of the Act being the provision of free instruction in the standard curriculum, parent payment requests by schools suggest that the delivery of instruction in the eight key learning areas increasingly relies on these contributions. Parent payments no longer just support free instruction, they have become essential to its provision. This means that the delivery of free instruction now depends on a school's interpretation of the parent payments policy. In the absence of a clear definition of free instruction, sufficient guidance and oversight from DET, free instruction now appears to have been watered down and limited in its application. Parents are increasingly being asked to pay for items that should be provided free.

DET does not know what the actual cost of free instruction is. It distributes available funds to schools based on an assessment of the needs of each school—predominantly based on a school's student population. Schools are not funded based on what it costs to deliver free instruction or to run an efficient school. The SRP should provide schools with sufficient funds for the provision of free instruction. However, DET cannot assure itself, schools or parents that SRP funding is sufficient. It is therefore not in a position to advise government on what funding schools require.

Accountability for school spending

Schools are largely autonomous and, as such, DET considers that it does not have the power to direct them on spending government funding or determining what payments are required of parents. Despite this, DET could, but has not, analysed how schools are using funding. Without this information it does not know whether the funds allocated through the SRP are sufficient and appropriate, and whether parent payment requests are reasonable. This is particularly important given that the SRP distributes funds based on relative need rather than actual cost. The oversight of school financial practices is essential to provide the government with assurance that its schools are complying with their legislative duty to provide free instruction.

Parent payment policies and practices

Schools continue to have difficulties in using DET's parent payment policy to develop and implement their own school-level policies. DET does not know how much money parents are being asked to pay to its schools, for what items, and whether this complies with requirements under the Act. Our survey of 366 schools identified that only 250 had parent payment policies. None of those fully complied with DET's policy requirements and the degree of their noncompliance varied significantly.

While recognising that it is not DET's role to define precisely what school-level policies should cover, noncompliance among some schools suggests that DET's policy:

- is unclear and is not well understood

- does not differentiate between what must be included in the school-level policy and what should inform a school's general understanding of parent payments—this means that essential elements of the policy, such as telling parents about the option to purchase items themselves, are lost among general parent payment advice and information.

DET should clarify its policy and guidance and define how it will verify school compliance with its policy.

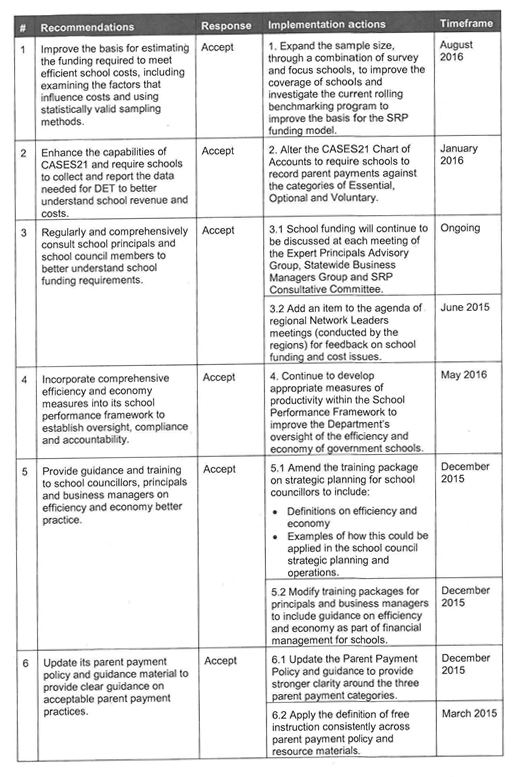

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- improves the basis for estimating the funding required to meet efficient school costs, including examining the factors that influence costs and using statistically valid sampling methods

- enhances the capabilities of CASES21 and requires schools to collect and report the data needed for it to better understand school revenue and costs

- regularly and comprehensively consults school principals and school council members to better understand school funding requirements

- incorporates comprehensive efficiency and economy measures into its school performance framework to establish oversight, compliance and accountability

- provides guidance and training to school councillors, principals and business managers on efficiency and economy better practice

- updates its parent payment policy and guidance material to provide clear guidance on acceptable parent payment practices

- regularly reviews school parent payment policies and practices, and intervenes where those practices are identified as breaching legislation or policy requirements.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Education and Training throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to the department and requested its submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 The right to education—free instruction

The right to education is contained within the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. As a signatory to these laws, the Commonwealth Government has agreed to uphold education as a human right in Australia. This commitment must, therefore, be reflected in Australian laws, policies and practices.

The premise of education as a human right relies on four principles, it must be:

- available—free and compulsory education for all

- accessible—free from discrimination

- acceptable—quality of teaching and learning

- adaptable—respond to interests of each child.

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (the Act) provides the legislative framework for education and training in Victoria. A key principle of the Act is that all young Victorians should have access to a high quality education. This includes access to free instruction in the standard curriculum program—eight key learning areas—for all young people under 20. Free instruction is not defined in the Act. The Department of Education and Training's (DET) Parent Payments in Victorian Government Schools policy defines 'free instruction' as including 'learning and teaching, instructional supports, materials and resources, administration and facilities required to provide the standard curriculum program'. Applying this definition allows for costs associated with teaching or instruction to be passed on to parents.

Throughout this report 'parents' is used to refer to parents or legal guardians.

1.2 Education funding and costs

In Victoria, the Act requires parents to enrol their children aged six to 17 years in a registered school or alternatively register for home schooling.

The standard curriculum program is made up of the arts, English, health and physical education, languages other than English, mathematics, science, studies of society and environment, and technology.

Government schools can charge fees for goods and services associated with the delivery of free instruction and for optional extra activities such as music lessons or a ski camp. They may also ask for donations to raise funds for other purposes. These charges are called school-level parent payments.

1.2.1 Government funding

Victorian government schools receive funding from both the Commonwealth and Victorian governments. In 2013–14, DET administered $5 484 million of Commonwealth and Victorian government funding to Victorian government schools—96 per cent of this is delivered through the school budget, known as the Student Resource Package (SRP). In addition, the Commonwealth provides $41 million of funding directly to Victorian government schools.

Essentially, the SRP is a large bucket of Commonwealth and state funding. DET does not determine how much money goes into that bucket—that is determined by government. DET distributes this SRP funding based on an assessment of each school's relative need against other schools, using attributes such as the number of students enrolled, individual student needs and the type of school. Therefore, school funding is not based on the actual costs associated with providing free instruction in the standard curriculum. Specific details of school funding arrangements are provided in the accompanying Victorian school funding explained information piece.

Victoria's reported expenditure for 2011–12 was $11 763 per primary school student and $15 032 per secondary school student. This is 14.4 per cent and 11.4 per cent below the national average respectively.

Figure 1A

Real, in-school, expenditure by state government schools

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

AUST |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary 2010–11 |

13 273 |

11 629 |

13 213 |

15 867 |

14 277 |

13 687 |

17 776 |

19 127 |

13 412 |

|

Primary 2011–12 |

14 123 |

11 763 |

13 292 |

15 573 |

14 499 |

14 225 |

17 898 |

19 987 |

13 734 |

|

Difference to national average |

2.8% |

–14.4% |

–3.2% |

13.4% |

5.6% |

3.6% |

30.3% |

45.5% |

|

|

Secondary 2010–11 |

15 649 |

14 896 |

16 188 |

22 077 |

15 605 |

16 276 |

20 412 |

23 777 |

16 289 |

|

Secondary 2011–12 |

16 749 |

15 032 |

16 790 |

22 714 |

16 128 |

16 771 |

21 595 |

24 916 |

16 965 |

|

Difference to national average |

–1.3% |

–11.4% |

–1.0% |

33.9% |

–4.9% |

–1.1% |

27.3% |

46.9% |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Report on Government Services 2014.

Responsibility for deciding how to spend allocated funding is devolved to schools to allow them to spend resources based on local need. The SRP has three funding components:

- student-based funding

- school-based funding

- targeted initiatives.

In 2013–14, the SRP allocated a total of $5 255 million. Figure 1B shows the SRP breakdown by component.

Figure 1B

Student Resource Package breakdown 2013–14

|

Funding component |

Funding ($ million) |

Funding (per cent) |

|---|---|---|

|

Student-based funding |

||

|

|

4 165 |

79.3 |

|

|

654 |

12.4 |

|

School-based funding |

348 |

6.6 |

|

Targeted initiatives |

88 |

1.7 |

|

Total |

5 255 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Education and Training data.

Student-based funding—core student learning and equity—is intended to cover the basic cost of a typical student's instruction in the standard curriculum program. It is calculated based on:

- the student, their family and community characteristics such as the occupation of the parents

- the student's disability and medical requirements

- whether English is a second language.

This component also provides additional funding to small and rural schools.

DET allocates school-based funding to schools for infrastructure needs such as cleaning, minor building works and grounds maintenance, and for specific programs including bus coordination, instrumental music programs and language assistants.

Targeted initiatives focus on areas such as primary welfare, senior secondary re-engagement and vocational training.

1.2.2 Parent payment policy

DET has developed a parent payment policy to guide school-level parent payments. This policy outlines three categories:

- Essential education items—items necessary to support instruction in the standard curriculum program such as books, stationery, uniforms and compulsory camps/excursions. Parents must pay for, or provide, these.

- Optional extras—items provided in addition to the standard curriculum, such as music lessons, personal photocopying and non-essential camps, excursions and social events. Parents pay for these items on a user-pays basis.

- Voluntary financial contributions—donations to the school for general or specific purposes, such as a building or library trust fund or for new computers. Payment of these contributions by parents is optional.

Each school council is responsible for creating its own school-level parent payment policy, which complies with DET's policy. A school's policy must ensure that, regardless of whether payments have been made:

- all students have access to the standard curriculum program

- all students are treated equally and none are disadvantaged.

Schools must also keep costs to a minimum, accurately cost items and itemise them in payment requests. Schools must not coerce or harass parents into paying charges, and the details of who has and has not made payments must remain confidential.

1.3 Parent payments

Parents are required to pay fees, charges and parent contributions across all states and territories in Australia. However, there is limited consolidated data available that outlines how much parents in Australian government schools are required to pay. Information on the total amounts that individual schools receive from fees, charges and parent contributions is available on the My School website—administered by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). However, that information only shows what was collected, rather than what schools asked for under their policies.

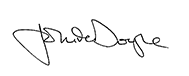

Figure 1C

Average fees, charges and parent contributions per school in 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority data.

ACARA data indicates that on average in 2012, each Victorian government school derived over $205 000 in parent payments. However, the payments shown in Figure 1C cannot be used as an indicator of individual parent payment costs across states as school size and student population variations affect school parent contribution figures.

DET's own financial data cannot be compared directly with the ACARA data due to methodological differences. However, it shows a similar trend to ACARA's data—that parent payments in Victorian government schools have risen by $70 million since 2009, a 29 per cent increase.

Figure 1D

Total parent fees, charges and contributions received by Victorian government schools

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Education and Training data.

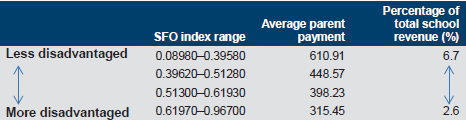

The amount of parent payments schools receive varies according to the school's socio-demographic. Figure 1E shows that schools with more disadvantaged students derive less income from parent payments. DET uses an index called the Student Family Occupation (SFO) to determine the socio-demographic status of its schools. It is calculated based on the occupation categories reported by the school's parents—the lower the range, the lower the disadvantage.

Figure 1E

Average parent payment by Student Family Occupation range for 2013

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Education and Training data.

1.4 Equity and the effect of exclusion

The current parent payment model allows each school to determine its own parent payment policies and its own hardship policies and procedures. This includes whether children whose parents cannot afford optional extra fees are included or excluded from optional extra activities such as non-essential camps, excursions and social events.

Welfare agencies have in recent years publicly expressed concerns about the effect of exclusion on a child's wellbeing—reporting that such exclusion can lead to low self‑esteem, behavioural issues, refusal to attend school and poor academic performance. They have also stated that the costs of essential education items such as school uniforms and information technology place a strain on the welfare agencies' available funds.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess whether DET and government schools are managing parent education costs economically, efficiently and effectively and in accordance with legislation and policies. To assess the objective, the audit examined:

- funding for the delivery of free instruction

- departmental oversight of school approaches to parent payments

- parent payments to support free instruction.

The audit scope focused on DET's parent payment policies and procedures and school funding policies and procedures that relate to parent payments.

This audit was commenced under the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). On 1 January 2015, machinery of government changes took effect and the responsibilities of the former DEECD transferred to the Department of Education and Training (DET).

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit surveyed 366 primary and secondary government schools to obtain budget and parent payment data, and examined in greater detail 12 primary and 12 secondary government schools. Schools were selected based on location, size and SFO rating.

The audit involved desktop research, document and file review, and interviews with DET staff and stakeholders. The audit examined levels of parent payment requests, compliance with legislation and policy, the adequacy and effectiveness of hardship procedures and accountability procedures.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of this audit was $500 000, which included $105 000 for the Victorian school funding explained information piece.

1.7 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the sufficiency of DET's school funding model

- Part 3 examines the adequacy of DET's guidance and oversight of school spending and parent payment practices

- Part 4 assesses the appropriateness of school parent payment policies and practices

- Appendix A. Victorian school funding explained

2 School funding for free instruction

2 School funding for free instruction

At a glance

Background

The Department of Education and Training (DET) administers school funding through the Student Resource Package (SRP). The SRP is intended to cover the cost of delivering free instruction in the standard curriculum. This includes the cost of teaching, leadership, administration and professional development.

Conclusion

DET has a limited understanding of the adequacy of school funding and the efficiency with which its schools are operating. Without this critical information, it cannot provide assurance that SRP funding is sufficient to meet the government's legislative obligation. There is evidence that schools are charging parents for items that should be free.

Findings

- Funding administered through the SRP is distributed based on relative need rather than the actual costs of providing free instruction.

- DET does not know the true cost of free instruction in the standard curriculum.

- DET does not know whether SRP funding is sufficient for the provision of free instruction in the standard curriculum.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- improves the basis for estimating the funding required to meet efficient school costs, including examining the factors that influence costs and using statistically valid sampling methods

- enhances the capabilities of CASES21 and requires schools to collect and report the data needed for it to better understand school revenue and costs

- regularly and comprehensively consults with school principals and school council members to better understand school funding requirements

2.1 Introduction

A sound analysis of school funding needs requires a clear understanding of what 'free instruction in the standard curriculum' means and what it costs to provide it. Providing this understanding is the role of the Department of Education and Training (DET).

2.2 Conclusion

The Student Resource Package (SRP) is meant to provide schools with sufficient funds to provide free instruction. However, DET cannot assure itself, schools or parents that funding is sufficient to provide free instruction. Nor can it advise government of the funding schools require.

DET's parent payment policy is vague in parts and not sufficiently prescriptive. Consequently, there is no shared understanding between DET and schools on the definition of free instruction in the standard curriculum or on the main elements of the three parent payment categories—essential education items, optional extras and voluntary financial contributions.

The types of payments requested by some schools suggest that parent payments no longer just support free instruction, they have become essential to its provision. Free instruction now appears to have been watered down and limited in its application. Essentially items that are free to some students are not free to others.

2.3 DET's definition of 'free instruction' is unclear

There is not one consistent definition of 'free instruction' in DET's policy and supporting documents, and the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 is silent on this matter. Differences in definition can lead to confusion. Schools interpret free instruction differently and some are charging parents for items and activities that should be free. For example, class sets of text books and materials that are held by the school such as paper, glue, tissues and paints. Figure 2A outlines the different definitions.

Figure 2A

DET definition of free instruction

Document |

Definition |

Parent Payments in Victorian Government Schools DET Policy |

Free instruction includes learning and teaching, instructional supports, materials and resources, administration and facilities required to provide the standard curriculum program. |

FAQ Sheet for Parents on DET Website |

Free instruction includes the provision of learning and teaching activities, instructional supports, materials and resources, and administration and facilities associated with the standard curriculum program. |

Template general information letter to parents from DET Parent Payment Support Materials for School Use |

Free instruction includes learning and teaching, instructional supports, materials and resources, administration and facilities associated with the provision of the standard curriculum program. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Education and Training data.

In response to this audit's findings, DET has amended its guidance material to provide a consistent definition of free instruction in line with its Parent Payments in Victorian Government Schools Policy.

An analysis of the guidance materials provided to schools demonstrates that the terminology used is confusing and results in incorrect categorisation. Figure 2B shows the various terminology used.

Figure 2B

DET rationale for each parent payment category

Essential |

Optional |

Voluntary |

|

|

|

Examples—excursions/camps where all students are expected to attend, consumables for learning and teaching where student consumes or takes possession of the finished articles. |

Examples—graduations/school formals, student insurance, school magazines, instrumental music program. |

Examples—contributions for a specific purpose identified by the school, general voluntary financial contributions, contributions to a building or library trust fund. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Education and Training data.

In its policy and guidance material, DET uses similar terms for 'free instruction' and the 'essential' payment category. For example, items that should be free are defined as 'associated with the provision of the standard curriculum program' and items deemed essential costs for parents are defined as 'associated with, but not part of instruction in the standard curriculum program'. It is important to make a clear distinction between the two and at present this is not the case.

As the terms used by DET are vague, such as 'associated with' and 'in addition to', they give schools greater flexibility to request payments from parents. Examples of items that should be provided for free but are being charged for by schools are:

- 'class sets' such as text books

- 'bulk classroom items' such as stationery, paper, art supplies, tissues

- 'head lice checks'

- 'administration supplies' such as paper, printer cartridges, photocopier/printer maintenance

- 'sporting equipment maintenance'

- 'information technology maintenance'

- 'first aid nurse'

- 'grounds maintenance'.

Out of 366 schools, 319 did not fully itemise parent payments—commonly listing one off amounts rather than categorising items. This practice masks requests for payments for items that should be provided for free.

Examples of things requested that did not itemise charges include:

- 'classroom consumables'

- 'curriculum resources/materials'

- 'curriculum contribution'

- 'bulk purchase supplies'

- 'books and materials'

- 'learning materials'

- 'communication costs'

- 'school equipment'

- 'shared requisites'.

In other cases, schools used the essential education items payment category and listed a charge without itemising this amount. One school gave parents the option of paying a fee of $525 for essential education items or paying a reduced amount of $300 for the same essential education items, if a $300 tax deductible donation was made to the school's voluntary building fund. In this instance, it is difficult to understand how the school's essential education items have been itemised and costed to the value of $525 if it is able to offer parents the same items for $225 less.

In one case a 'building and grounds' charge was levied to cover—maintenance of playgrounds, soft-fall and equipment, managing OHS within the school, management of trees, and fencing. In another, the school's 'Student Resource Charge' was said to ensure:

- 'air conditioning to all classrooms

- regular contract cleaning

- students with good access to emerging technologies—for example, computers, iPads, iTouches, interactive whiteboards, etc

- access to unfunded DET programs—for example, literacy Intervention, extensive specialist curriculum programs, such as music, arts, health and physical education, and to supplement the cost of funding programs to improve delivery

- student wellbeing programs'.

Part of the rationale for requesting payments for essential education items is that parents will only be expected to pay for items that the student actually consumes or takes possession of. The examples provided above clearly demonstrate that the intention of the policy has been lost in practice. Parents rely on a school's correct interpretation of the parent payment categories to ensure that requests are made in accordance with Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (the Act) and DET policy. Currently this is not the case.

DET has produced guidance for schools on administering the parent payments policy which includes a Payment Categories Flowchart—including specific examples of what schools can and cannot charge parents for. However, this guidance is not always clear and schools continue to charge parents for items that should be provided for free. Either the guidance is not being used by schools or is not understood by them. This guidance is discussed in Part 3 of this report.

2.4 Student Resource Package

The SRP should provide schools with sufficient funds to provide free instruction. However, DET distributes available funding based on the relative needs of schools rather than actual cost of delivering free instruction.

DET has not sought to fully understand the actual costs of providing free instruction, an activity that could lead to securing further funding for its schools. It has not sought to provide government with any advice on the adequacy of government school funding in recent years. DET has not been able to provide assurance that the overall funding for schools is in fact adequate.

All the principals interviewed during the audit said that SRP funding is inadequate and does not reflect the real cost of delivering free instruction. This view is also supported in several position papers produced by the Victorian Principals Association, which outline concerns about the inadequacy of school funding in areas including:

- cleaning provision in schools

- cuts to frontline services

- facilities and maintenance provision

- grounds allowance

- occupational health and safety requirements.

Attempts by principals to apprise DET of this have had no impact.

Inadequacies in DET's financial databases—CASES21 and eduPay—make it difficult to examine the overall adequacy of SRP funding and schools' use of specific SRP components. These systems do not record expenditure based on the same categories that the funding is allocated under, meaning that components such as student-based funding and equity funding cannot be examined.

One component that can be examined is funding provided for school infrastructure activities, such as cleaning, maintenance and utilities. These items are readily identifiable in both the SRP funding allocation and school expenditure records.

Figure 2C compares infrastructure funding and expenditure in 2013 for the 24 audited schools. It shows how much schools are underspending or overspending as a proportion of their allocated SRP amount. For the majority of schools visited, the SRP allocation was insufficient to cover the actual operating and maintenance costs, with some schools spending up to 248 per cent over their allocated budget. Across the 24 audited schools, there was a net overspend of almost $3.5 million. Only three schools underspent their infrastructure budget.

Figure 2C

2013 SRP allocation and recorded school expenditure of 24 schools

for school infrastructure activities

School |

Total allocated $ |

Total spend $ |

Variance $ |

Variance % |

1 |

247 449.25 |

860 502.56 |

–613 053.31 |

–247.7% |

2 |

370 240.41 |

1 030 769.87 |

–660 529.46 |

–178.4% |

3 |

338 969.22 |

941 591.93 |

–602 622.71 |

–177.8% |

4 |

319 971.51 |

854 511.61 |

–534 540.10 |

–167.1% |

5 |

234 241.35 |

509 168.83 |

–274 927.48 |

–117.4% |

6 |

30 136.48 |

60 081.89 |

–29 945.41 |

–99.4% |

7 |

369 500.40 |

586 948.68 |

–217 448.28 |

–58.8% |

8 |

426 382.70 |

659 809.25 |

–233 426.55 |

–54.7% |

9 |

422 692.54 |

620 188.72 |

–197 496.18 |

–46.7% |

10 |

24 149.13 |

34 689.88 |

–10 540.75 |

–43.6% |

11 |

149 761.51 |

211 208.66 |

–61 447.15 |

–41.0% |

12 |

109 226.52 |

152 578.59 |

–43 352.07 |

–39.7% |

13 |

69 003.35 |

92 957.48 |

–23 954.13 |

–34.7% |

14 |

53 187.52 |

68 395.09 |

–15 207.57 |

–28.6% |

15 |

88 163.87 |

108 425.34 |

–20 261.47 |

–23.0% |

16 |

71 459.53 |

83 976.83 |

–12 517.30 |

–17.5% |

17 |

129 846.46 |

148 628.60 |

–18 782.14 |

–14.5% |

18 |

23 572.84 |

25 366.65 |

–1 793.81 |

–7.6% |

19 |

31 099.60 |

32 766.40 |

–1 666.80 |

–5.4% |

20 |

230 568.74 |

236 816.98 |

–6 248.24 |

–2.7% |

21 |

105 791.52 |

106 133.45 |

–341.93 |

–0.3% |

22 |

43 612.16 |

42 663.58 |

948.58 |

2.2% |

23 |

130 949.79 |

104 319.10 |

26 630.69 |

20.3% |

24 |

234 749.81 |

167 293.45 |

67 456.36 |

28.7% |

Total |

4 254 726.21 |

7 739 793.42 |

–3 485 067.21 |

–81.9% |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on unaudited school data from CASES21.

This is not the first time we have reported this issue. In our 2012 report Implementation of School Infrastructure Programs we highlighted that government schools received only 32 per cent of the recommended level of ongoing investment. Figure 2C illustrates the continuing pressure this places on schools. We are currently examining DET's response to the findings of our 2013 report as part of our follow-up program.

2.5 Student-based funding

Student-based funding is intended to cover teaching and learning, leadership and administration, professional development, relief teachers, payroll tax and superannuation for the school. It comprises around 90 per cent of the total school budget.

However, there are issues around DET's calculation of funding:

- student-based funding is based on studies that compare the relative costs faced by different types of schools with different student cohorts, rather than the actual cost of operating those schools.

- studies used to inform the funding model had inadequate sample sizes and only examined high-performing schools.

- the rural school size adjustment factor is based on out-dated demographic data and can result in the unfair allocation of funds when schools have multiple campuses.

- the Student Family Occupation rating, which measures disadvantage, is inadequate.

2.5.1 Research underpinning the student-based funding model

The current student-based funding model was initially derived from a 2004 study of school core expenditure commissioned by DET. However, there are limitations with this study and subsequent benchmarking reviews.

None were based on a statistically representative number of schools:

- the 2004 study was based on a sample of only 42 out of a total of 1 626 schools.

- the 2008 study was based on a sample of only 83 out of a total of 1 585 schools.

- the 2012 study was based on a sample of only 103 out of a total of 1 537 schools.

As a result of the small samples sizes, some conclusions about proposed expenditure and the relative needs of particular types of schools were based on a single school's data.

Further, none of the studies referenced actual dollar amounts for expenditure on core instruction. Rather they identified the costs of teaching and learning across every year level and then weighted each year level according to relative expense. This precludes any analysis of actual SRP funding against the reports' findings to test for adequacy of funding.

Because these studies looked only at patterns of resource use in schools identified as being effective and efficient, across all school type, size and location groups, as well as student socio-economic status, it did not consider whether the initial funding available to schools—before it is weighted across year levels—is sufficient. In analysing school expenditure, the studies examined the costs of 'delivery of education'. However, it is unclear what this consists of and whether it is reflective of a school's obligation to provide free instruction in the standard curriculum program.

2.5.2 Aligning the student-based funding model to teaching profiles

Among the 24 audited schools, principals expressed concerns about trying to match SRP funding to actual wage costs. Principals were concerned that the SRP has not been increased in line with teacher wage increases and did not consider a school's teacher profile in terms of graduate through to experienced teachers.

The SRP's current funding model forces principals to choose between hiring cheaper graduate teachers or retaining experienced teachers and creating a wage deficit. The wage differentiation between the two types of teachers is around $30 000 per annum. This was particularly problematic for principals in rural areas as it was difficult to attract new teachers to the area and they knew it would be difficult for their experienced teachers to find work elsewhere if retrenched from their local school. However, as discussed below, DET does provide additional funding to rural and remote schools aimed at addressing the challenges associated with these types of schools.

2.5.3 Addressing issues of size and rurality

The student-based funding component of the SRP includes three categories that support small schools; enrolment-linked base funding, small school base funding and a rural school size adjustment factor. DET's 2012 study identified that this was unnecessarily complex and promoted inconsistencies. It also found that:

- the funding criteria for the rural school size adjustment factor may be supporting larger multi-campus schools over smaller single campus schools which exceed the 'per campus' eligibility criteria

- despite additional funding, small rural primary schools are underperforming academically compared to urban and larger rural schools

- two different boundary measures are used to identify whether a school is outside urban centres, which causes confusion and inconsistency—the two sets of boundaries have not been updated within the past 10 years.

These findings were confirmed by the 12 rural schools examined in this audit. Our 2014 audit Access to Education for Rural Students identified that DET's activities to assist rural schools have not resulted in a significant improvement in performance.

2.5.4 Addressing disadvantage

Social and financial disadvantage is measured based on parents' occupations. DET uses an index called the Student Family Occupation (SFO) to target additional funding towards those students whose readiness to learn is affected by a range of circumstances, including prior educational experiences and family or other personal circumstances.

However, the SFO has limitations. A parent's occupation does not always reflect their level of education, the family's values and the student's willingness to learn. The 2012 study discussed the concerns of some schools that the SFO index does not reflect the real differences between schools. It also reported challenges associated with collecting accurate and current data on parental employment status. Among the 24 audited schools, all principals expressed concerns about parents misrepresenting their occupational status. Parents would primarily do this to avoid their children being associated with what they perceive to be social stigmatisations.

One principal gave an example of a parent who was a qualified doctor overseas but drove a taxi in Australia. That parent reported his occupation as doctor. Some rural principals expressed similar concerns about farmers stating their occupations to be senior managers in large business organisations. These practices result in schools receiving lower SFO ratings than they should, which causes them to be deemed more privileged than they are. This has the potential to affect a school's eligibility for SFO funding.

2.6 School-based funding

School-based funding provides for school infrastructure and programs specific to individual schools. DET provided a total of $348 million of school-based funding to schools in 2014. This is an average of $616 per student.

2.6.1 Maintenance and minor works funding

All schools are provided with recurrent funding for maintenance as part of the SRP. The funding formula distributes 50 per cent of the available maintenance funds based on each schools current and/or projected enrolment as a proportion of the state total. This formula is flawed as it is calculated based on student numbers rather than the school's actual building footprint.

The remaining 50 per cent of funds is distributed based on each schools building construction material and relative condition. This formula if flawed as funds are distributed based on relative need, not on the actual costs of maintenance.

DET acknowledges that maintenance funding is below the recommended threshold. However, DET maintains that its focus has been on maximising the effectiveness of the available funding in maintaining the $16.2 billion asset base. Of the $420 million in investment required to bring the buildings up to an acceptable standard in 2012, DET committed $50.1 million in 2013–14, and $94 million in 2014–15. Its stated strategies include targeting resources to the assets in greatest need of repair and providing emergency funding to schools that require serious maintenance.

2.7 The Education Maintenance Allowance

Up until January 2015, a payment was available to low income families to help with the costs of education such as books and excursions. This was known as the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA). Payments were made annually and ranged from $150 to $300 depending on the year level of the student. In 2014, 159 543 students received EMA payments.

The EMA was either paid directly to parents or, if the parent requested, paid directly to the school to be used for items as determined by the parent. Therefore, schools were required to use EMA funding for the disadvantaged students to whom it was targeted, with close parental oversight.

In 2013, the Victorian Government announced that the EMA would be abolished at the end of 2014 and alternative funding provided directly to schools. DET will provide this additional funding to schools through the SRP equity funding component. However, it is unclear how principals will be able to identify those students in need of additional support.

DET argues that under the devolved school model, schools have complete flexibility within their budgets to address the specific needs of students, and that it is the responsibility of school councils to develop policies and plans to allocate funding.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

1. improves the basis for estimating the funding required to meet efficient school costs, including examining the factors that influence costs and using statistically valid sampling methods

2. enhances the capabilities of CASES21 and requires schools to collect and report the data needed for it to better understand school revenue and costs

3. regularly and comprehensively consults with school principals and school council members to better understand school revenue and costs.

3 DET guidance and oversight of school spending

3 DET guidance and oversight of school spending

At a glance

Background

Under the school autonomy model, school councils, with the assistance of the principal, determine how school funds are used and how much parents are required to pay. The Department of Education and Training (DET) considers that its role under this model is primarily to provide guidance and support—rather than oversight and regulation—to schools in relation to budget and financial management.

Conclusion

DET does not know how schools spend funds or what amounts parents are being asked to pay. DET cannot assure itself that parents are not paying for items that should be provided for free.

Findings

- Funding administered through the SRP is distributed based on relative need rather than the actual costs of providing free instruction.

- DET's financial management training is essential and appropriate. However, DET does not know how many current principals and business managers have completed it.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- incorporates comprehensive efficiency and economy measures into its school performance framework to establish oversight, compliance and accountability

- provides guidance and training to school councillors, principals and business managers on efficiency and economy better practice.

3.1 Introduction

Under the government's school autonomy model, each Victorian Government School Council, with the assistance of the principal, determines how to spend allocated government funding and how much to request from parents. In order to be efficient, effective and economical, schools require strong management teams who, among other things, are capable of sound budget and financial management. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DET) believes its role is primarily to provide guidance and support—rather than oversight and regulation—to schools in relation to budget and financial management.

3.2 Conclusion

DET should—but does not—know how much parents pay to government schools or for what specific purposes. Without this information, DET cannot know if the Student Resource Package (SRP) funding is sufficient to support free instruction and if schools are complying with policy or the Education and Training Reform Act 2006.

DET considers that under the school autonomy model, it does not have the power to direct schools on how to spend government funding or determine what payments are required of parents. Despite this, DET could but has not analysed how schools are using their funds. This would allow it to determine whether parent payment requests are reasonable, whether funding is sufficient and whether schools are operating efficiently. The oversight of school financial practices is essential to provide the government with assurance that its schools are complying with its legislative duty to provide free instruction.

3.3 Parent payments

DET does not collect detailed information on how much schools ask parents to pay and how much they do pay. DET's financial database, CASES21 does not enable schools to record parent payments according to the three types of payments—essential educational items, optional extras and voluntary financial contributions. Instead, they can be recorded as subject contributions, sale of class materials, camps/excursions/activities and donations. With the exception of donations, these categories do not reflect DET's policy definitions of the parent payment categories. Our attempts to analyse CASES21 data also identified that parent payment data cannot be easily and accurately extracted, mainly because subject contributions and sale of class materials are recorded inconsistently across schools.

Further complicating matters, some schools use additional systems to manage their budget and finances. These systems sit separately to CASES21 and contain greater detail about the school's management of funds. DET does not have access to these systems nor even an awareness of which schools are and are not using them.

Without a breakdown based on the three parent payment categories, DET cannot undertake a fundamental analysis of parent payment amounts and trends, and cannot know if schools are complying with policy and the Act.

3.4 Student Resource Package funding allocation

DET does not provide schools with detailed information on the intended purpose of each component of the school's SRP funding. While this approach aligns with the autonomous schools model being pursued in Victoria, a more detailed funding breakdown would assist schools to make informed decisions.

DET provides each school with an SRP Budget Details Report along with its advice on that school's SRP funding allocation for the following year. However, the SRP Budget Details Report provides a high-level breakdown only of how funding for the school was calculated. With the exception of school infrastructure, the SRP does not tell schools the intended purpose of each component of SRP funding.

3.5 School Council Financial Audit

DET's School Council Financial Audits (SCFA) have shown that schools are not accountable for their practices. If the autonomous schools model is to be successful, DET needs to exercise its own oversight role by providing clear guidance to schools and hold them to account for their efficient, effective and economic operation, as well as their educational performance. DET has been aware of schools' deficient parent payment practices since at least 2011. However, in 2014, school noncompliance is still rife.

DET conducts an annual SCFA. The 2013 SCFA looked at 451 schools and found:

- errors in coding transactions in CASES21

- a lack of compliance with DET policies and procedures

- administrative errors or oversights

- a lack of management oversight by principals

- a lack of school council governance and monitoring

- inadequate internal controls and poor financial management.

The SCFA noted that 27 per cent of business managers in audited schools lacked a basic understanding of accrual accounting procedures. In line with its 2012 findings, the audit found that:

- some business managers lacked the skills required to undertake their role

- not all principals, despite having responsibility for reviewing financial information, had adequate financial knowledge

- school councils were not supported by adequate financial reports, there were insufficient school council meetings and inadequate minutes of school council decisions

- some schools had inadequate internal controls, such as cash handling and segregation of duties procedures.

These findings were particularly evident in small schools.

DET is attempting to address the issues identified by the SCFA by promoting financial training to principals, business managers and school council members. It has also provided additional financial support to schools in need of assistance. However, despite DET's training being of a high standard, it does not know how many current principals and business managers have completed the training, nor does it have the capacity to identify those that have not.

DET's financial support to schools is provided through its technical leadership coaches for principals and by school financial liaison officers for business managers. There are only 2.5 full time equivalent technical leadership coaches and four full time equivalent school financial liaison officers to service all schools in Victoria. Through necessity, their roles have evolved into a reactive, rather than proactive one—helping schools that have been identified as being in wage deficit or identified by the SCFA as requiring assistance.

Given that the issues identified in the 2013 SCFA are similar or the same as those identified in 2012, it is imperative that DET do more to assist schools to improve their financial management practices. Further, it is essential that DET evaluate the outcomes of its attempts to address school noncompliance. Without such evaluation, DET cannot assure itself that its strategies have achieved greater compliance or whether further work is required.

3.6 Training

An analysis of the training manuals DET uses to provide financial management training to principals and business managers indicates that the training is thorough and appropriate. Some school principals and business managers involved in the audit also confirmed that the training was useful, however, not all principals and business managers have completed it.

While the training is appropriate, it is concerning that the 2013 SCFA found business managers and principals lacked financial management knowledge and skills.

DET is currently in the process of formulating an accreditation process for business managers. The project aims to professionalise the business manager role in recognition of its important school management function. As this project has not been finalised, this audit could not analyse its outcome. However, the project should, if implemented successfully, lead to greater access to training for business managers. Given training and accreditation will be provided online, DET could use the training process to gather data on business managers' knowledge gaps, and inform future training strategies.

3.7 Parent payment audit

In 2011 DET engaged a contractor to conduct a review of whether school-level policies and payment requests complied with DET policy. Thirty-seven schools were surveyed in the following areas:

- continuation of services to students

- Education Maintenance Allowance

- payment administration

- funds management

- school-level policy

- communication to parents.

The audit concluded that schools were generally both aware of and complied with DET policy. However:

- school-level policies do not always comply with DET's policy

- requests for parent payments are not always correctly categorised and itemised

- schools do not always provide appropriate notice for payment requests

- parents are not always provided with the option to purchase essential education items themselves.

The most common cause of noncompliance was misinterpretation of the requirements of DET's policy due to its complexity. Accordingly, the review recommended that DET refine and simplify the policy and provide a clearer description about what information should be included within school-level policies.

The review identified a number of examples of good practice, including using DET templates and processes surrounding the Education Maintenance Allowance.

In response to the review's recommendations, DET restructured its parent payment policy and developed additional support materials for schools. However, the guidance remains confusing and vague.

The review did not examine schools compliance with all areas of the policy, including:

- the processes undertaken by schools to determine costs

- the amounts schools are requesting from parents

- whether these amounts are appropriate

- whether schools are using payments for purposes for which they were sought.

Without an analysis of these areas, there are significant gaps in DET's understanding of the practices of schools. It also cannot identify what the potential causes of noncompliance are, their implications or what needs to be addressed.

3.8 School efficiency, effectiveness and economy

The school autonomy model requires school councils, with the assistance of their principals, to be responsible for how government and other sources of funding are spent. To achieve the maximum benefit from limited available resources, schools must achieve the following three attributes:

- economy—the acquisition of the appropriate quality and quantity of resources at the appropriate times and at the lowest cost

- efficiency—the use of resources such that output is optimised for any given set of resource inputs, or input is minimised for any given quantity of output

- effectiveness—the achievement of the objectives or other intended effects of activities at a program or entity level.

DET has never reviewed whether schools are economical, efficient or effective. In fact, DET struggles to identify what such a school should look like. Economical, efficient and effective schools require, among other attributes:

- strong governance from school councils and strong management teams

- skilled school budgeting and financial management

- sound workforce management and deployment, including high-quality teachers

- a focus on ongoing teacher professional development

- involvement of parents in student education

- strong ties with the community.

DET's current School Performance Framework has some elements that measure a school's productivity, viability and workforce. These include net cash and credit position, condition of school and growth in enrolments. However, these measures do not provide an indication of which schools are:

- using their resources economically—best value for money

- working efficiently—achieving more with available resources

- working effectively with the school community to achieve outcomes.

DET needs to do more to understand school capabilities in these areas and identify and assist those schools in need of training and support.

DET's current strategy, Improving School Governance, aims to strengthen the governance role of school councils. Training provided through this program will include strategic planning, finance and policy, and review. This strategy, along with the business manager accreditation project, shows promise.

3.8.1 School efficiency practices

The audit survey showed that school efficiency practices vary considerably. Responses provided on how schools reduce costs included:

- reducing energy usage and waste

- reducing staff

- employing graduate teachers

- reducing curriculum spend

- reducing student support programs

- re-using unfranked postal stamps

- deploying alternative arrangements in lieu of casual relief teachers

- utilising volunteers/parent labour

- negotiating bulk purchases and obtaining three quotes

- using private cars instead of buses for outings

- digitising newsletters.

Figures 3A highlights some typical school survey responses.

Figure 3A

Reducing school operational costs

'Reduced staffing, worked harder, reduced support programs for children with literacy and numeracy needs, carried out maintenance tasks ourselves, e.g. unblocked toilets, repaired furniture, tried to cut down gas and electricity expenses, tried to change utilities provider from those locked in by DET—unsuccessfully so far.' |

'More working bees asking parents to volunteer their time to help with maintenance. Principal now mows the lawns, cleans windows and generally keeps all classroom buildings outside in a reasonable state of repair, after he has fulfilled his obligation as a classroom teacher and one day administration.' |

'We have ceased the use of bottled gas and heat the school with our more cost efficient reverse cycle air conditioner. We obtained a grant for a ride-on lawnmower which is used by a volunteer, reducing the cost of maintaining our grounds. We also have a group of parents who come and do gardening and cleaning up around the school grounds monthly. Grants have been obtained to fund school improvements to help with activities such as a pizza oven, kitchen garden and greenhouse. We grow our own vegetables and have chooks to supply ingredients for cooking/healthy living lessons. We access the LAB [Local Administration Bureau] services to reduce the amount of admin time. Our business manager has been made excess and the school will make further use of the LAB and hire a less expensive business manager and for reduced hours in 2015. We have also obtained a fortnightly visit from the Shire MARC Van [Mobile Area Resource Centre] in 2014.' |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office survey of government schools.

To some extent, it is appropriate for schools to use differing efficiency practices because practices should be tailored to suit each school. However, there are some effective cost-saving practices that could be utilised across schools but are not. DET could do more to inform itself on effective school cost-saving measures and should share success stories with other schools.

3.9 Parent complaints about school costs

DET predominantly manages parent complaints through its regionally-based community liaison officers (CLOs). Prior to May 2014, CLOs did not record complaints consistently and, in some instances, not at all. Further, DET has not sought to analyse parent complaints to ascertain whether there are areas of concern or developing trends that need to be addressed. This is a missed opportunity.

We spoke with CLOs who advised that parent payments are a common source of complaint. They expressed concerns that DET head office does not consult with them on policy and guidance development. In May 2014, DET piloted the Contact Management Project which, subject to funding, will enable all CLOs to input all parent complaints received by telephone into a centralised database. This is a step in the right direction for DET, however, it is too early to examine the collected data and DET's use of it.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

4. incorporates comprehensive efficiency and economy measures into its school performance framework to establish oversight, compliance and accountability

5. provides guidance and training to school councillors, principals and business managers on efficiency and economy better practice.

4 Parent payment policies and practices

At a glance

Background

Schools are responsible for managing their own budget, finances, policies and procedures. The Department of Education and Training (DET) requires schools to develop and administer a parent payment policy that aligns with its own broad parent payment policy.

Conclusion

Despite DET having a parent payment policy, templates and guidance, schools are not following them. Even where schools' parent payment policies predominantly complied with DET's policy, the payments they requested from parents did not. This means that parents are not being given enough information about what they are paying for—in some cases items that should be provided for free. Parents are also being denied sufficient time to pay, not being provided with alternative options for payment—payment plans—or given an opportunity to source cheaper alternative items themselves.

Findings

- DET's policy and guidance material is vague in parts and confusing.

- None of the school-level policies examined completely complied with DET's policy.

- No parent payments reviewed during the audit included all of the information required by DET policy.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- updates its parent payment policy and guidance material to provide clearer guidance on acceptable parent payment practices

- regularly reviews school parent payment policies and practices, and intervenes where identified practices are breaching legislation or policy requirements.

4.1 Introduction

School councils are required to create and administer school-level parent payment policies and practices that comply with the Department of Education and Training's (DET) policy. This includes determining what items and amounts are charged to parents.

Under a devolved school model, it is important that compliance and better practice be driven by DET to ensure schools administer parent payment requests appropriately.

4.2 Conclusion

Schools continue to have difficulties developing and administering parent payment policies that fully comply with DET's policy requirements and the requirements of the Education and Training Reform Act 2006. Our survey of 366 schools revealed that only 250 had school policies, and none completely complied with DET's policy requirements. The degree of these noncompliances varied significantly.

This is not a new issue. A DET review conducted in 2011 identified that schools were not complying with all the requirements then. Almost four years later, compliance with this policy remains poor. The lack of accountability by DET for the collective failure of its schools to consistently and fairly administer a parent payment policy is poor public administration.

DET's policy is not sufficiently clear and remains poorly understood by some schools. Given the significance of these issues and the lack of incentives for the schools to address them, DET needs to take decisive action.

4.3 Schools' parent payment policies

Schools are required to have a parent payment policy that has been ratified by its school council. These policies should provide a clear school position regarding parent payments, should promote transparency and should make schools accountable for their decisions about what to charge parents for. Despite this, not all schools have a parent payment policy. Of those that do, not all policies are ratified by the school council or compliant with DET policy. Of the 366 schools surveyed, 68 per cent had a policy and 31 per cent of these were not ratified by the school council.

DET provides guidance materials to support schools in developing their school-level policy, including a policy template, payment request template and parent communication templates. However, in spite of this assistance, an analysis of 250 school policies, detailed in Figure 4A, shows that no school complied with all elements of DET policy.

Figure 4A

School-level parent payment policy compliance

with DET policy requirements

Requirement |

Included in policy (number) |

Absent from policy (number) |

School policy compliance (%) |

Continued access to standard curriculum despite no payment |

190 |

60 |

76 |

Commits to not withholding enrolment access or year advancement despite no payment |

132 |

118 |

53 |

Includes and defines three parent payment categories |

204 |

46 |

82 |

Commits to keeping costs to minimum |

116 |

134 |

46 |

Items will be accurately costed |

73 |

177 |

29 |

Parents can purchase essential items themselves |

118 |

132 |

47 |

Payments can be requested but not required until first day of term one |

105 |

145 |

42 |

Provide information on financial support options |

137 |

113 |

55 |

Provides information about alternative payment arrangement options |

211 |

39 |

84 |

Parent payment status kept confidential |

207 |

43 |

83 |

Provides information on how to apply for Education Maintenance Allowance |

91 |

159 |

36 |

Payment arrangements will coincide with Education Maintenance Allowance payments |

139 |

111 |

56 |

Parents will not be pressured into signing over the Education Maintenance Allowance |

57 |

193 |

23 |

Commits to providing early notice of requests—at least six weeks prior to end of previous year |

159 |

91 |

64 |

Commits to not coerce or harass parents for payments |

78 |

172 |

31 |