Casual Relief Teacher Arrangements

Overview

Casual relief teachers (CRT) are a significant and vital part of the school education system, yet they receive only limited support from the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) and schools.

CRTs are professionally qualified teachers who can be engaged by schools for up to 30 continuous days at a time. They provide continuity of learning for students during normal teacher absences and enable permanent teachers to access extended professional development opportunities. CRTs represent about

12 per cent of the teacher workforce.

DEECD has not developed an approach to understand the location, availability and skills of the CRT workforce. Without this knowledge it is not well placed to develop evidence-based policy and make informed strategic decisions about the CRT workforce.

There is also a lack of assignment of responsibility for monitoring and supporting CRTs. This means that the impact of the CRT workforce on student outcomes and teaching quality is not being managed. As casual teaching is clearly a statewide issue, DEECD needs to work more closely with the Victorian Institute of Teaching and other agencies to understand the CRT workforce and make sure that action is taken when needed to address inequity and make sure that skilled and experienced CRTs are available when and where they are needed.

Casual Relief Teacher Arrangements: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER April 2012

PP No 117, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Casual Relief Teacher Arrangements.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

18 April 2012

Audit summary

The Council of Australian Governments’ Smarter Schools National Partnership for Improving Teacher Quality identifies teacher quality as the most important in-school influence on student outcomes. Over the past decade, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has focused on teacher quality as key to engaging students in school life and helping them achieve the best possible results. DEECD has identified that teacher learning needs to be ongoing, long term, sustained, and should occur at all levels of the system.

Casual relief teachers (CRT) are professionally qualified teachers who can be engaged by schools for up to 30 continuous days at a time. They provide continuity of learning for students during normal teacher absences and enable permanent teachers to access extended professional development opportunities.

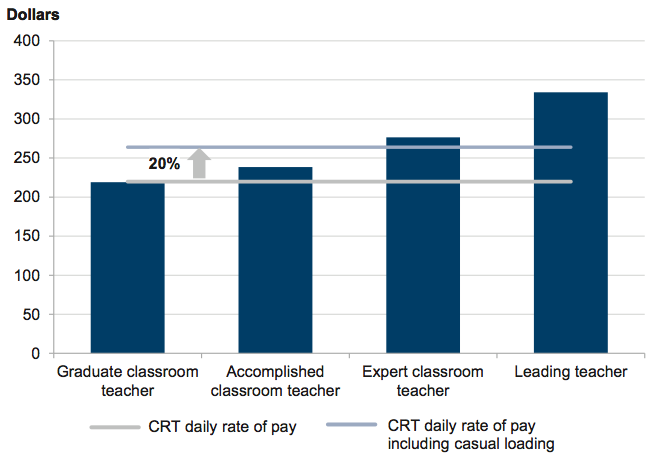

About 12 per cent of registered teachers identified themselves as a CRT when surveyed in 2007. This equates to over 13 000 teachers in 2011. On average a student is exposed to about three hours of CRT teaching every week. The number of CRTs employed in government schools has risen by 36 per cent since 2000, making schools more reliant on CRTs than ever before.

CRTs experience many of the problems associated with other casual workforces. They are paid less relative to permanent staff, have no opportunity to improve pay or conditions through performance, are not supported or funded to participate in professional development activities and have limited professional redress when they feel they have been unfairly treated.

However, unlike many other casual workforces, they operate in a highly regulated environment dominated by the government sector, and they have a direct influence on the learning experience of Victorian school students. To be able to teach, CRTs need to meet all of the same professional requirements as any other teacher, but must do so without the same support provided to other teachers by schools and DEECD.

This audit assessed whether the use of CRTs in government schools has contributed effectively to student outcomes and teaching quality.

Conclusions

There are significant cultural and procedural barriers that constrain CRTs from contributing effectively to student outcomes and teaching quality.

The audit did not assess the quality of CRT’s classroom teaching and it is not possible to quantify the direct impact of CRTs on student outcomes. However, CRTs are subject to the same professional standards as permanent teachers and schools react quickly and decisively to remove poorly performing CRTs.

CRTs are a significant and important part of the teacher workforce, yet schools use them in a very reactive way and give little thought to providing them with sufficient resources, managing their performance, and developing their skills. Many schools perceive CRTs to be little more than classroom ‘babysitters’. CRTs perceived by schools to be performing poorly are often isolated from teaching opportunities and are unable to improve their practice and further their careers.

CRT use and availability is not uniform across the state, and regional and remote schools find it more difficult to source CRTs when required. This means that students in regional schools are at greater risk of disadvantage from a lack of skilled and experienced CRTs. A further issue is that fewer regional than metropolitan schools use CRTs to enable their teachers to participate in DEECD’s Teacher Professional Learning program. It is therefore not evident that CRTs are being used effectively to improve student outcomes and teaching quality.

When suitably skilled and experienced CRTs are not available, some schools have had to resort to undesirable solutions such as cancelling specialist classes and spreading students across different classes (class splitting)—removing them from their peer group and disrupting the receiving classes.

DEECD has not developed an approach to understand the location, availability and skills of the CRT workforce. Without this knowledge it is not well placed to develop evidence-based policy and make informed strategic decisions about the CRT workforce.

While CRTs are a vital part of the school education system, they receive only limited support from DEECD and schools. Unlike permanent teachers, they are not contractually affiliated or connected to a particular school or to the government, independent or catholic school sectors. There is, however, a lack of assignment of responsibility for monitoring and supporting them. This means that the impact of the CRT workforce on student outcomes and teaching quality is not being managed. As casual teaching is clearly a statewide issue, DEECD needs to work more closely with the Victorian Institute of Teaching and other agencies to understand the CRT workforce. DEECD should take action when needed to address inequity and make sure that skilled and experienced CRTs are available when and where they are needed.

Findings

Supporting casual relief teachers

CRTs and permanently employed teachers in Victoria have to meet the same professional standards before they can teach in schools. These standards include holding a teaching qualification and completing both 10 days of teaching practice and 20 hours of recognised professional development every year. Further, to work in government schools, they must understand and comply with school and DEECD policies.

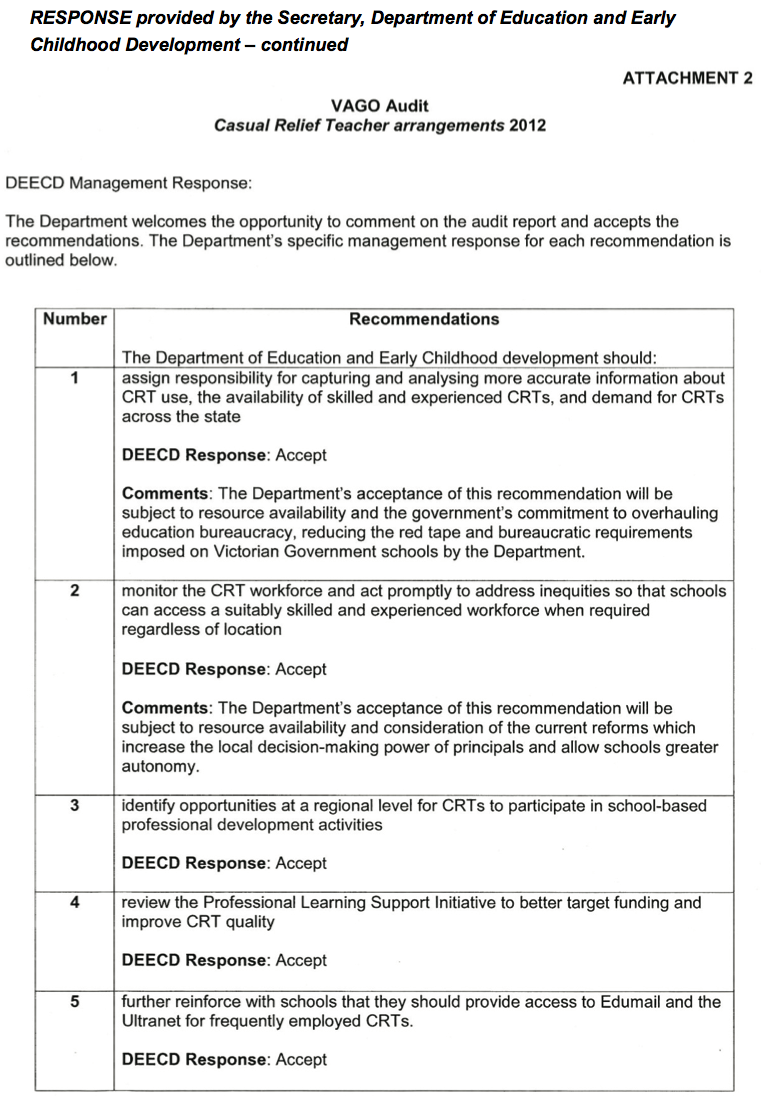

CRTs in Victoria are paid less than CRTs in other states and the same as graduate teachers in Victoria. They are often not provided with the resources they require to teach effectively and receive little or no support and professional development from schools. Figure A compares arrangements for CRTs and permanent teachers.

Figure AComparative arrangements for casual relief teachers and permanent teachers in government schools

CRT |

Government school classroom teacher |

|

|---|---|---|

Professional development |

CRTs are required to complete 20 hours professional development each year. CRTs organise their own professional development and are not paid to attend. |

Teachers are required to complete 20 hours professional development each year. Schools organise and pay for professional development from within their school budget. Teachers are able to attend professional development as part of their teaching role. |

Employer |

Employed by schools or CRT agencies. |

Employed by DEECD. |

Daily pay rate |

$219.83 plus a 20 per cent casual loading. Single classification for all CRTs. |

Three classifications (graduate, accomplished, expert) each divided into sub divisions:

|

Maximum income per year |

$52 760 (working every day of the 40 teaching weeks of the year). |

Minimum graduate salary: $56 985. Maximum expert teacher salary: $84 056. |

Salary progression |

None. |

Salary progression cycle completed annually, based on achievement against criteria determined by the school. |

Leave entitlements |

20 per cent casual loading. |

Standard leave provisions including:

|

Performance management |

None. |

A performance review is undertaken at the end of each salary progression cycle. |

Teaching resources |

No Edumail account and no automatic access to the Ultranet. |

Edumail account and automatic access to the Ultranet. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

If schools perceive a CRT to be underperforming they will not re-employ them and often share this advice informally with other schools. CRTs have no redress in these situations and this informal ‘word-of-mouth’ approach can present significant barriers to gaining future work, especially in regional areas. This creates a vicious circle for the CRTs as they are denied opportunities to improve their skills through practical experience, which in turn prevents them from demonstrating their capabilities and securing further work, and risks their teacher registration from the Victorian Institute of Teaching.

Schools do not help CRTs to identify and address the cause of any underperformance, and do not support CRTs to develop skills and capabilities. Audited schools did not routinely invite CRTs to participate in school-run professional development activities. This is not consistent with the principles of DEECD’s Accountability and Improvement Framework and associated performance development culture.

DEECD does not monitor either the performance of the CRT workforce as a whole, or the type of professional development undertaken by CRTs working in government schools. While it has provided almost $1 million over two years to assist CRTs to attend professional development activities, uptake has been poor and participation restricted to areas where volunteer-run CRT networks have already been established. DEECD cannot explain why uptake has been so low.

Casual relief teacher supply and demand

DEECD does not have accurate data on CRT supply and demand. The number, location, skills and experience of CRTs is unknown as there is no central database or registration requirement for teachers to identify as CRTs. DEECD’s annual CRT census only asks schools about CRTs employed and does not capture data on unmet demand, i.e. situations when schools could not recruit a CRT. Therefore DEECD cannot gauge the number of CRTs its schools need, the location, or the size or skills and experience of the overall pool of available CRTs.

DEECD’s 2010 census data shows that on average, each school employed 1.2 full time equivalent CRTs. Estimates of the CRT workforce show that at any given time there should be six CRTs available to every school, meaning that supply should outweigh demand. In reality, the number of CRTs does not remain constant throughout the year, nor are CRTs evenly spread across the state. DEECD does not have enough data to confirm the distribution of skills and experience.

From 2001 to 2010, the number of CRTs employed in government schools rose by 39 per cent, with the biggest increases occurring in major metropolitan growth areas. Sick and carer leave by teachers has also increased by 8 per cent over the same period, but data is not available on other types of teacher absences such as attending camps or excursions and professional development. Without this additional data, DEECD cannot identify trends and make informed decisions about whether the future supply of CRTs is sufficient to meet demand from schools, and whether CRTs are suitably skilled and experienced.

Of the CRTs employed by government schools, 68 per cent are located in metropolitan areas. However, the ratio of CRTs to permanent teachers is similar across all schools. Schools in regional areas report more difficulty in recruiting CRTs. Students at regional schools may, therefore, be more disadvantaged by teacher absences than students in metropolitan schools.

Secondary schools generally have a larger and more flexible teacher workforce than primary schools. It is, therefore, not surprising that primary schools are much more reliant on CRTs. In 2010, primary schools employed 2.7 CRTs for every 10 permanent teachers compared with only 1.4 in secondary schools.

Schools have systems in place to manage teacher absences, and prepare a budget to cover CRT use throughout the year. However, schools rarely budget adequately for CRTs and often by term four, when teacher sick leave is at its highest, they have little or no CRT funds left. This can lead to classes being split up, students being removed from their peers and specialist classes being cancelled.

Sourcing casual relief teachers

Schools can develop their own list of CRTs to call on when needed or, where available, they can use recruitment agencies to source CRTs.

Schools pay a significant cost premium (about 22 per cent higher) for agency CRTs, but avoid the administration burden of maintaining their own list. The number of schools using agency CRTs has increased since 2005, but agencies usually only operate in metropolitan or densely populated regional areas. Therefore, many regional schools have no access to agency CRTs.

During periods of high demand, metropolitan schools can draw on the large agency CRT pool. Regional schools meanwhile must compete directly with each other to secure the best CRTs from limited pools.

Supporting teacher professional development

DEECD provides funding through its Teacher Professional Leave (TPL) program so that schools can employ CRT cover for teachers taking extended professional development. Since the TPL program was established in 2004, over $32 million has been provided to 998 schools for professional development for 4 761 teachers. DEECD’s evaluations of the program suggest that it is a valuable investment in improving teacher skills.

Participation in the TPL program is dominated by teachers who work in metropolitan and major urban areas. DEECD has not done any recent work to understand and address the barriers to participation for non-metropolitan teachers. However, it is clear that unless more is done to help regional schools obtain CRTs to cover planned TPL absences, the impact of this program will remain restricted.

Other than through DEECD’s TPL program, schools rarely use CRTs as part of a coordinated strategy to contribute to teacher quality by enabling teachers to participate in planned professional development activities.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- assign responsibility for capturing and analysing more accurate information about CRT use, the availability of skilled and experienced CRTs, and demand for CRTs across the state

- monitor the CRT workforce and act promptly to address inequities so that schools can access a suitably skilled and experienced workforce when required regardless of location

- identify opportunities at a regional level for CRTs to participate in school-based professional development activities

- review the Professional Learning Support Initiative to better target funding and improve CRT quality

- further reinforce with schools that they should provide access to Edumail and the Ultranet for frequently employed CRTs.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1. Background

1.1 Introduction

It is widely acknowledged by educational researchers and practice experts that teacher quality is the single greatest in-school influence on student engagement and achievement. Improving teacher quality has been a core focus of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) over the past decade.

If a teacher is absent from class, their replacement, known as a casual relief teacher (CRT), can have a significant influence on the students’ learning experience. It is therefore vital that schools have a sufficient pool of high quality replacement teaching staff that are readily available to cover teacher absences. A 2010 census by DEECD reported that CRTs taught approximately 12 per cent of all classes in government schools.

CRTs are qualified teachers who are engaged by schools to:

- replace a teacher on unplanned leave such as sick leave

- replace a teacher undertaking other duties or professional development

- carry out a specific task or activity that requires a qualified teacher for a short period, for example to maintain teacher/student ratios on school trips.

Schools use a number of strategies to manage teacher absences, including using executive teaching staff such as assistant principals in classroom roles, redeploying other teaching staff, and employing short-term CRTs. But if schools do not budget sufficiently or cannot access suitably skilled and experienced CRTs, their options are restricted and they may resort to undesirable practices such as splitting up a class and moving students into other classes.

There are currently over 13 000 registered teachers who identify themselves as CRTs, but it is not clear where, or how regularly, they work. DEECD’s census of CRT use in schools, conducted from 2–6 August 2010, reported that 1 365 (87 per cent) of government schools employed one or more CRTs during the census week. In total, during this period, government schools employed 8 350 CRTs.

1.2 Employing casual relief teachers

Schools operate within the legislative framework of the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (ETRA). Under ETRA the school council has the power to employ CRTs on a casual basis for up to 30 consecutive working days.

Direct employment of CRTs by schools contrasts with the situation for permanent teaching staff who are directly employed by DEECD. CRTs are also employed by private agencies that provide staff to schools under commercial ‘labour-hire’ arrangements.

1.2.1 Employment requirements

CRTs need to be registered to teach, or given permission to teach, by the Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT). Therefore, they have the same professional registration requirements as other teachers, namely that they:

- hold an appropriate teaching qualification

- complete at least 10 days teaching or equivalent practice each year

- do at least 20 hours of recognised professional development each year. VIT recognises a wide range of professional development, including attending courses and seminars, attending professional meetings such as working parties or committees, and study that leads to a formal qualification

- obtain a current and satisfactory National Criminal History Record Check

- declare any charges or convictions in relation to their professional conduct, competence or capacity as a teacher.

Schools often provide professional development for their permanent staff but are not required to provide professional development for CRTs.

1.2.2 Employment conditions

The conditions of employment for CRTs, including rates of pay, are set out in the ETRA Ministerial Order No. 200.

CRTs are paid for the actual hours they work to the nearest 15 minutes between a minimum of $131.90 (for three hours work) and a maximum of $263.80 (per day). Victorian CRTs are paid less than CRTs in any other state, and are paid at the equivalent rate of a graduate teacher regardless of their level of experience.

The Victorian CRT rate of pay includes a 20 per cent loading that reflects the casual nature of the work and is in lieu of annual leave, personal leave, and public holidays. Victoria is one of only two states (the other being Queensland) where CRTs do not have an incremental salary structure whereby teachers can earn more based on their performance and experience.

Figure 1A shows the respective equivalent daily pay rates for CRTs and other teacher classifications in Victoria.

Figure 1A

Daily rates of pay for teachers in Victoria

Note: Teacher daily rates shown in this graph are the commencement level salaries calculated based on a 52 week working year.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Victorian Government Schools Agreement 2008 and the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 Ministerial Order No. 200.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

School councils usually delegate to school principals the responsibility to employ suitable and eligible teachers as CRTs. Prior to engaging a CRT, the school must be satisfied that they meet DEECD’s requirements for employing teaching staff, including checking whether they are registered to teach.

The school must also make sure that all pre-employment requirements are met when employing a CRT through an agency. DEECD has advised schools that when employing persons not known to them, schools should check with previous employers to make sure that these people are suitable for employment and that the CRT does not have any employment or re-employment restrictions placed on them. A pre‑employment check must be done on DEECD’s central payroll system.

DEECD’s central and regional offices support schools to manage teacher absences by providing guidance and advice but do not monitor or control the use, quantity or quality of CRTs.

1.4 Funding of casual relief teachers

DEECD funds government schools via the Student Resource Package, which is a school’s main source of income, and is calculated from February student enrolment data. This funding allows schools to employ teaching staff, including CRTs.

In the 2011 calendar year, the entire Student Resource Package budget was worth around $4.5 billion, with about $3.0 billion spent on permanent teacher salaries. Schools spent a further $150 million on CRTs.

DEECD has provided an additional $32.6 million since 2004 for the Teacher Professional Leave program. This program funds schools to hire CRTs to allow permanent teachers to undertake extended professional development.

Recognising that the quality of CRTs is also important, DEECD has set up a program to help CRTs access professional development. This program, the CRT Professional Learning Support Initiative has provided $930 000 since 2010.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

This audit assessed whether the use of CRTs in government schools has contributed effectively to student outcomes and teaching quality.

The audit examined DEECD’s policies, guidelines and practices and the activities of 30 schools in both metropolitan and regional Victoria.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $285 000.

1.7 Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the use of CRTs in providing continuity of teaching

- Part 3 examines the quality of CRTs.

2 Use and impact of casual relief teachers

At a glance

Background

Schools use casual relief teachers (CRT) to manage both planned and unplanned short-term teacher absences. In primary schools, they are often the first choice, while secondary schools have more flexibility within their workforce and timetabling systems to cover teacher absences by redeploying existing staff.

Conclusion

Schools that are able to employ a CRT when needed generally use them effectively to manage teacher absences. However, variations in supply are disadvantaging schools in some regional areas. If the number of CRTs used by schools continues to increase, so too will the CRT supply problems experienced by regional schools. Responsibility for monitoring and managing the availability of CRTs in the workforce, and for addressing regional shortages, needs to be assigned to make sure that all schools can access suitably skilled and experienced CRTs when needed.

Findings

- While the overall number of CRTs should be sufficient to meet government school needs, demand is increasing and regional variations in CRT supply and demand make it hard for some schools to hire suitably skilled and experienced CRTs.

- The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) does not monitor the CRT workforce and does not know if all of its schools can access CRTs when needed.

- A lack of skilled CRTs and a failure to manage CRT budgets by some schools is resulting in undesirable responses to teacher absence such as splitting classes.

- DEECD’s Teacher Professional Leave program is allowing teachers to undertake extended professional development by funding CRT cover. However, CRT shortages in regional areas are limiting access by some schools.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- assign responsibility for capturing and analysing more accurate information about CRT use, the availability of skilled and experienced CRTs, and demand for CRTs across the state

- monitor the CRT workforce and act promptly to address inequities so that schools can access a suitably skilled and experienced workforce when required regardless of location.

2.1 Introduction

Schools use casual relief teachers (CRT) to provide continuity of teaching to students when a regular teacher is absent. These absences may be planned, such as long service leave or professional development, or unplanned, such as when a teacher is ill.

According to data from The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s (DEECD) Teacher Supply and Demand Report, over the past decade there has been an increase in the number of teachers taking sick/carer’s leave (8 per cent), long service leave (83 per cent) and family leave (55 per cent).

Following structural changes to the management of government-provided education in the 1990s managing CRTs became a school responsibility. School councils are now responsible for employing CRTs, replacing the prior practice of regional DEECD offices allocating CRTs on a daily basis. This was part of a wider move to increase autonomy of school councils and give greater flexibility to meet school needs. Victoria and Western Australia are the only states in Australia that do not centrally manage CRTs.

CRTs provide continuity of teaching and assist schools to deliver student learning outcomes and as such, they must be available and effectively managed.

2.2 Conclusion

CRTs are an important part of schools response to teacher absences and are a significant part of the teacher workforce. Teacher absences are increasing, making schools more reliant on CRTs to maintain the quality and continuity of student learning.

Audited schools had strategies in place to manage teacher absences, including using CRTs. Schools also closely monitored the performance of the CRTs they employed to make sure they did not have an unduly negative impact on student outcomes. However, fluctuations in supply and demand and budgetary pressures mean that the option to use a CRT was not always available which, in some cases, resulted in schools adopting less desirable solutions to manage teacher absences.

Based on estimates of the number of CRTs in Victoria, there should be enough to meet the needs of schools across the state. However, schools in regional areas continue to find their availability a challenge. CRTs are now being used more than ever and without intervention, the current imbalance in supply will be exacerbated.

DEECD does not take an active role in making sure that schools can access CRTs when needed. The minimal data it has available means it cannot know whether there is sufficient quantity of skilled and experienced CRTs to meet the needs of all government schools.

Teacher absences are highest in term four, resulting in a peak in demand for CRTs. However, this is also the time when schools will have most difficulty accessing them. By this stage of the school year, many of the more skilled and experienced CRTs have been appointed to fixed term or permanent positions and many schools have already exhausted their CRT budget.

This may result in students being separated from their classmates as classes are split up to cover the absence and meet recommended average class sizes. It also means that some teachers are unable to attend professional development during term four because their school has exhausted the CRT budget.

Since 2004, DEECD has provided $32.6 million to schools to enable teachers to participate in extended professional development through the Teacher Professional Leave (TPL) program. This program has been used by 4 761 teachers and evaluations show that it has improved the capacity and skills of teachers in Victoria.

However, participation in the program requires schools to source an appropriately skilled CRT, which is not always possible. Participating schools and teachers mainly come from metropolitan areas and major regional centres where it is easier to get CRTs. This is a constraint on the uptake of the TPL program, which has flow-on effects for the ongoing professional development of the permanent teaching workforce.

2.3 The role of casual relief teachers

Schools use CRTs as one of a number of strategies to maintain the continuity of their teacher workforce and student learning. For primary schools, CRTs are generally the first option to cover absences, while secondary schools have more flexibility with class timetabling and are better able to divert existing resources without having to resort to splitting classes and removing students from their peers.

DEECD does not have a position on splitting classes but 29 of the 30 principals interviewed for this audit agreed that splitting classes was less desirable than employing a good CRT.

2.3.1 Prevalence of casual relief teacher use

Every August, DEECD conducts a census of schools to understand how they use CRTs. The census is conducted over the course of a week and requires schools to record the number of CRTs used during that week.

Schools reported that, during the 2010 census week, they engaged CRTs to work for more than 70 000 hours. This equates to an average of 1.2 full time equivalent CRTs per school.

On average, every student had about three hours of contact time with a CRT each week (10 per cent of the school week) or 20 days per year. Primary schools use more CRTs than secondary schools, employing 2.7 CRTs for every 10 permanent teachers compared to only 1.4 in secondary schools. In 2010, primary schools used twice as many CRTs as secondary schools, despite them only having 20 per cent more teachers.

Budget constraints in term four can limit the capacity of schools to use CRTs. Term four is also the time of the year with the highest incidence of sick leave taken by teachers. This combination can lead to classes being split up, students separated from their peers and specialist classes being cancelled.

2.3.2 Sourcing casual relief teachers

When schools decide to use CRTs they have two options: compile and use their own list of CRTs to draw on, or use a recruitment agency.

Schools manage their own lists by short-listing favoured CRTs and removing those they perceive to be poor performing. Since 2005, the number of CRTs employed through agencies has increased by 36 per cent from 1 712 to 2 330.

School casual relief teacher lists

School CRT lists include teachers who previously worked at the school and are on family leave, recently retired teachers, graduate teachers, or teachers who prefer to work as a CRT. Audited schools used less than half of the CRTs on their list regularly and removed poorly performing teachers from their lists.

Many audited schools said that highly skilled and experienced CRTs do not stay as CRTs for long. High performers are often given fixed-term contracts and quickly become permanently employed. This makes it all the more important that DEECD acts to better understand and improve the skills of the remaining CRT workforce.

Better performing CRTs are also likely to be on multiple lists held by government and non-government schools. As a result, schools in the same locality are competing against each other for high performing CRTs who can ‘cherry pick’ preferred schools and/or positions. This can make it more difficult for some schools to attract suitably skilled and experienced CRTs.

Agency casual relief teachers

Since the 1990s, when the responsibility for employing CRTs was devolved to schools, there has been an increase in the number of recruitment agencies specialising in the provision of CRTs. Agencies supplying CRTs are commercial entities that employ a pool of CRTs, and other school staff, that they supply to schools when needed. They allocate individual CRTs and invoice the schools for their time. Agencies are responsible for paying the CRTs. Schools pay a premium of about $60 per day for agency CRTs but avoid the administrative burden associated with sourcing and employing CRTs directly.

CRT agencies usually operate in metropolitan or more densely populated regional areas. While 31 per cent of CRTs employed during the 2010 census period were sourced through an agency, many regional schools have no access to agency CRTs because of their location.

There are two main types of agreement between agencies and schools:

- standard agreement—agency CRTs are available to schools when needed and the agencies invoice the schools for CRT time

- exclusive agreement—same as the standard agreement except that schools agree to source CRTs exclusively from that agency and receive a discounted rate in return.

A number of issues relevant to the use of CRT agencies by schools are being reviewed by DEECD but are yet to be resolved. In particular, DEECD, schools, and WorkSafe do not have a clear understanding about who is responsible for WorkCover costs when schools engage CRTs through agencies. DEECD first identified this issue in 2007 but it is still unresolved.

Most schools incorrectly assume that CRT agencies are responsible for checking the registration of CRTs, and as a consequence, rarely check the registration of these CRTs. This increases the risk that an unregistered teacher may be able to work in a school undetected.

2.4 Casual relief teacher supply and demand

Overall estimates of the number of CRTs suggest that there are sufficient CRTs in Victoria to meet school needs. However, the picture is different in various areas of the state, and schools in regional Victoria have more difficulty sourcing CRTs than metropolitan schools.

2.4.1 Casual relief teacher supply

There are currently more than 113 000 registered teachers in Victoria and around 72 500 of these (64 per cent) are permanent teaching staff working at government, Catholic or independent schools. However, the number of available CRTs is not known as there is no central database or registration requirement for teachers to identify as a CRT.

The most recently available CRT workforce information, a 2007 survey by the Victorian Institute of Teaching’s, found that 12 per cent of registered teachers identified themselves as CRTs. Based on this ratio, approximately 13 600 registered teachers would currently identify as CRTs. It is not clear if any non‑active but registered teachers are, or could be, available for CRT work throughout the year.

Figure 2A shows the current estimated distribution of registered teachers.

Figure 2A

Estimated distribution of registered teachers in 2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis based on Australian Bureau of Statistics and Victorian Institute of Teaching data.

Graduates and future casual relief teacher supply

DEECD has implemented a number of initiatives to attract, retain, train and retrain government school teachers. These include initiatives under the Teacher Quality National Partnership as well as targeted scholarships. DEECD believes these initiatives will increase the size of the CRT workforce by increasing the overall teacher workforce, however, it cannot quantify this.

New graduates are also an important component of the CRT workforce and central to capacity to meet needs in the future. After graduating, teachers are provisionally registered to teach for up to two years. During this time, they need to obtain full registration by meeting the Victorian Institute of Teaching’s professional practice standards, including completing at least 80 days of classroom teaching.

The school preference of using ‘known’ CRTs can make it difficult for graduate teachers to obtain regular CRT work and meet the requirements for full teacher registration.

Casual relief teaching should be a viable option for graduates who cannot secure permanent or fixed-term positions and should represent a structured way to enter the teaching profession. However, for this to be effective, DEECD and schools need to be able to identify, engage and support these graduates which they currently cannot do. If these graduate teachers cannot get enough work to meet the full registration requirements it is plausible that they will leave the profession.

2.4.2 Demand for casual relief teachers

While DEECD knows how many CRTs its schools employ, it has limited information about demand for CRTs from its schools and across the education sector as a whole. DEECD also does not know the specialisation, skills, experience, location and availability of teachers who work as CRTs. Therefore, it cannot be sure that the CRT workforce is sufficient to meet the needs of schools, and it is not evident that CRTs are being used effectively to improve teaching quality and student learning outcomes. DEECD’s failure to monitor the CRT workforce means that local problems may remain undetected and unresolved.

During the 2010 census period, schools employed 8 350 CRTs with the majority (68 per cent) employed in the four metropolitan regions. Based on the above estimates of the supply of CRTs, at any given time there should be six CRTs available to each school in the state, suggesting that supply is evenly distributed.

The number of CRTs employed by government schools has increased by 36 per cent, from 6 162 in 2000 to 8 350 in 2010. By contrast, the number of government school students has only increased by 1 per cent and the government school teacher workforce overall has only increased by 7 per cent in the same time. Therefore, CRTs are playing an increasing role in student learning.

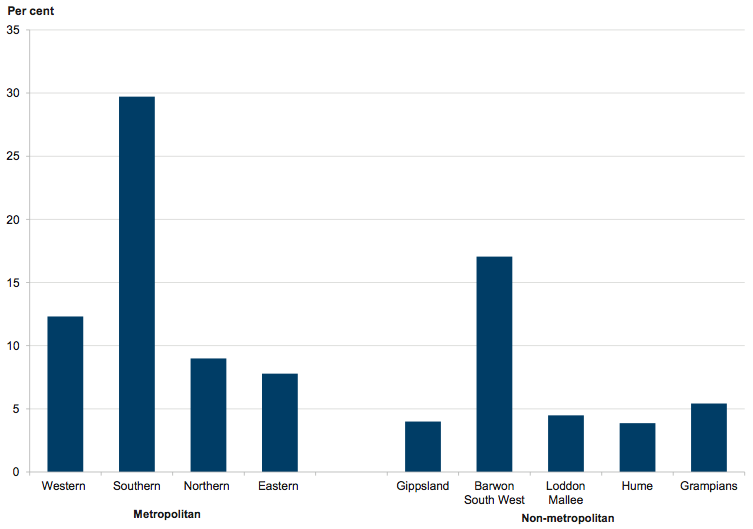

The biggest increases in CRT use have occurred in the major metropolitan areas and more specifically in the major growth regions. However, use of CRTs in Barwon South West and Gippsland regions has also increased significantly.

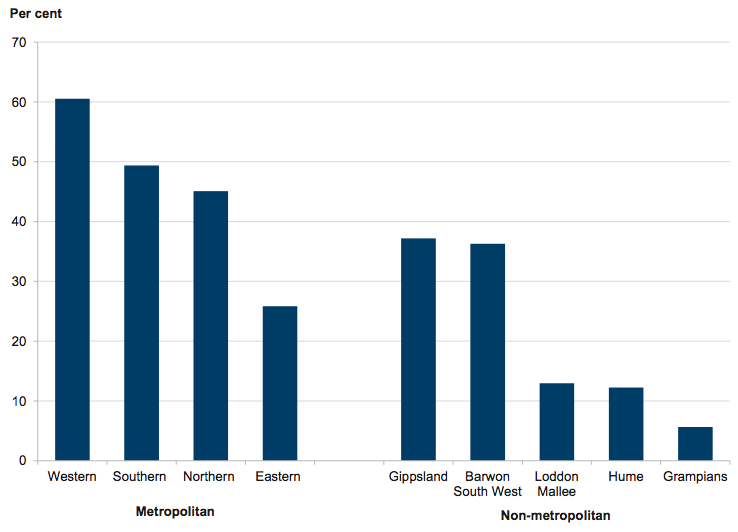

Figure 2B shows the percentage increase in the number of CRTs being employed in each region between 2000 and 2010.

Figure 2B

Increase in the number of casual relief teachers employed between 2000 and 2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Department of Education and Early Childhood Development CRT Census data.

Challenges in meeting demand

In the past ten years the number of ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ CRT positions has decreased by 49 per cent, from 2 016 in 2000 to 1 021 in 2010. ‘Difficult‑to‑fill’ vacancies are those requiring more than three phone calls, or contact with more than one source, to obtain a CRT. They are DEECD’s only way of understanding demand for CRTs and whether there are any significant shortages in the workforce.

However, ‘difficult-to-fill’ vacancies are measured in DEECD’s census of CRTs and provide an imprecise measure of demand, specifically they do not:

- capture changes in demand across the year, as ‘difficult-to-fill’ vacancy data is collected during term three when the highest demand for CRTs is likely to be in term four

- capture unmet demand, which is the number of positions where schools wanted to employ a CRT but could not do so.

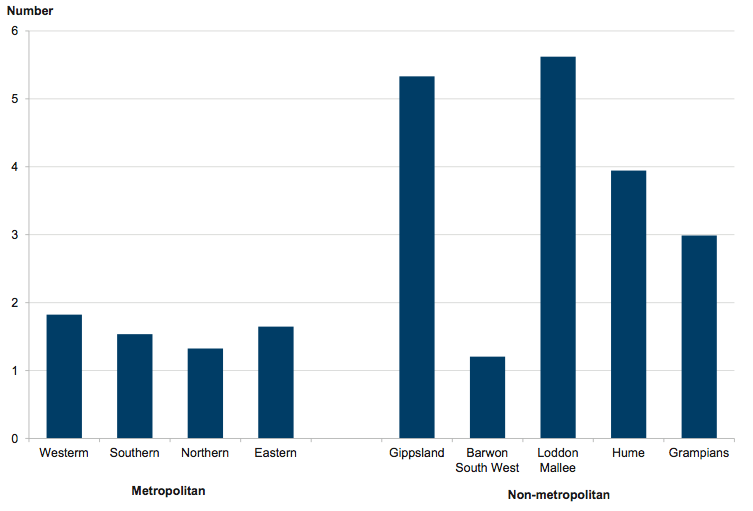

Comparing the ratio of CRT ‘difficult-to-fill’ positions to the number of teachers employed shows that regional schools have more difficulty filling CRT positions than metropolitan schools. In 2010, Loddon Mallee and Gippsland regions had the largest ratio of ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ vacancies to of all regions.

Figure 2C illustrates the relative problems experienced by regional schools in recruiting CRTs when compared to their metropolitan counterparts.

Figure 2C

Number of regional ‘difficult-to-fill’ casual relief teacher vacancies per 100 teachers

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Department of Education and Early Childhood Development CRT Census data, August 2010.

While difficulties in sourcing CRTs are generally addressed in metropolitan schools by using CRT agencies, these are often not available to regional schools. Students at regional schools may therefore be more disadvantaged by teacher absences than students at metropolitan schools.

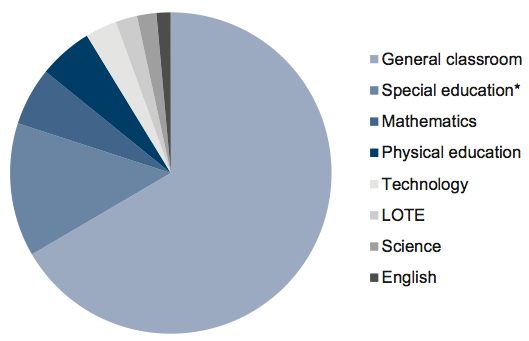

General classroom teachers are the most commonly reported CRT ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ position (64 per cent) with relatively few schools experiencing problems sourcing more specialist CRTs. This reflects the higher overall use of CRTs by primary schools which are less likely to need specialist teachers.

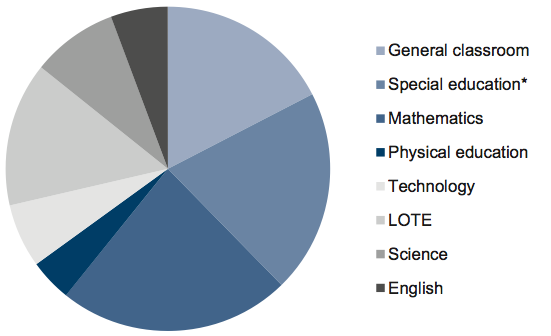

By comparison, across the permanent and fixed-term teacher workforce, ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ positions are more likely to be for specialists. This illustrates the need to separate CRT resources from the general teacher workforce when calculating and managing demand at a system-wide level.

Figures 2D and 2E show the distribution of the most common ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ positions for CRTs and the general teacher workforce.

Figure 2D

Casual relief teacher ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ positions

Note: *Specialist teachers employed to assist students with identified special educational needs.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

Figure 2E

Permanent and fixed term teacher ‘difficult‑to‑fill’ positions

Note: *Specialist teachers employed to assist students with identified special educational needs.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

School budgeting

Each school sets its own CRT budget from its Student Resource Package funding. This allocation is based on an assessment of known (planned) teacher absences, and an estimate of unknown absences based on previous years.

However, 20 of the 30 audited schools had spent more than their annual CRT budget by the end of term three and 28 had spent more than their planned budget to that date.

While schools gather data on staff absences, approved leave, sick leave and staff turnover, they do not analyse types of teacher absences to identify trends and plan accordingly.

School principals are required to oversee the effective budgeting of their school’s funds. Despite having access to data that would allow them to better budget for CRT use, it is still being poorly done.

2.5 Casual relief teachers’ role in enabling professional development

DEECD has identified that if it could improve the quality of teaching, this would in turn improve student learning outcomes. CRTs can provide cover for teachers attending professional development and are therefore an important resource that schools can use to improve teacher quality and consequently student learning outcomes.

DEECD has also identified that teacher learning needs to be ongoing, long term, sustained, and should occur at all levels of the system. For this to happen, teachers may need to take planned leave from the classroom to further develop their professional skills.

The Teacher Professional Leave (TPL) program was established by DEECD in 2004 to help teachers access extended professional development by providing funding for CRT cover during their absence. In this way, CRTs underpin the continuing development of the permanent teacher workforce.

Even when they are available, CRTs are seldom used to facilitate teacher professional development outside the DEECD funded TPL program. CRTs are more often seen by schools as last minute solutions to last minute problems, such as teacher illness.

2.5.1 The Teacher Professional Leave program

Teachers approved to participate in the TPL program take between 25–50 days of professional leave to pursue their area of interest. To date 4 761 teachers from 998 schools have participated, at a cost of $32.6 million. This equates to an average of $6 851 per teacher, or 26 days of CRT time, and is therefore a significant investment in the teacher workforce.

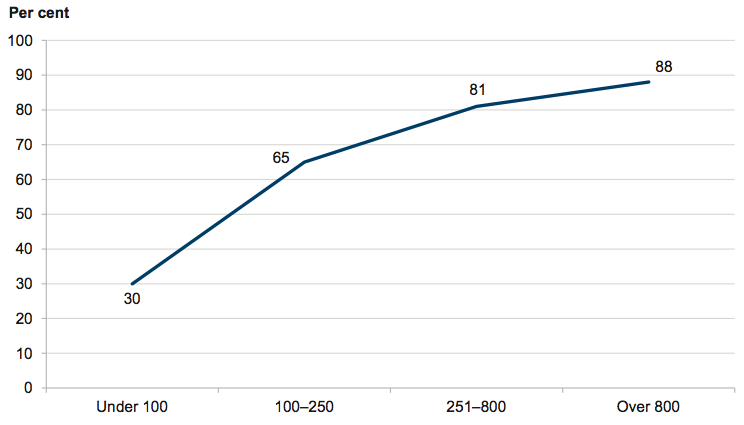

DEECD evaluations show that the TPL program is effective and has assisted more than 10 per cent of government school teachers to undertake extended professional development. However, participation is heavily weighted towards larger metropolitan schools which can more easily access CRTs and cover staff absences.

Use of casual relief teachers in the Teacher Professional Leave program

DEECD has regularly evaluated the TPL program. These evaluations conclude that the program is a valuable investment in the capacity and skills of teachers. DEECD is also conducting a longitudinal study to determine what impact the program is having on student outcomes.

However, in the eight years that the program has been running, only two-thirds of schools have accessed the program and DEECD has not done any recent work to understand which schools are (not) participating and barriers that may prevent schools from using the program.

Participation in the TPL program is dominated by schools in metropolitan regions. Consistent with this, metropolitan schools have less difficulty filling CRT vacancies than regional schools. Figure 2F shows TPL program participation across the state.

Figure 2F

Government school participation in the Teacher Professional Leave program – 2010

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

There is also a significant discrepancy in participation across different sized schools. Almost all schools in the state that have more than 800 students (88 per cent) have had at least one teacher participate in the program. TPL participation drops to 30 per cent of schools with less than 100 students. Eighty-three per cent of schools that have not participated in the TPL program were primary schools.

Figure 2G shows the correlation between school size and participation.

Figure 2G

Teacher Professional Leave program participation by schools based on student population

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office analysis of Department of Education and Early Childhood Development data.

While some secondary schools have successfully used alternative scheduling strategies to create free time for teachers to participate in the TPL, the availability of skilled and experienced CRTs is critical to the success of the TPL program, particularly for primary schools.

2.5.2 Other professional development

Schools also support the professional development of their teachers outside the TPL. However, this is funded from general school budgets allocated by DEECD under the Student Resource Package. The Student Resource Package does not explicitly factor in the cost of engaging CRTs for this purpose.

As CRT budgets are regularly exhausted before the end of the year, a common response by the audited schools was to freeze or scale back planned professional development of permanent teachers in term four.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- assign responsibility for capturing and analysing more accurate information about CRT use, the availability of skilled and experienced CRTs, and demand for CRTs across the state

- monitor the CRT workforce and act promptly to address inequities so that schools can access a suitably skilled and experienced workforce when required regardless of location.

3 Quality of casual relief teachers

At a glance

Background

Teacher quality is vital to student engagement and results. Casual relief teachers (CRT) play an important role in a student’s school experience. It is therefore important that the CRT workforce is adequately skilled, supported and developed.

Conclusion

Neither the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) nor schools adequately support CRTs. Although they both need to more actively monitor and manage the quality of the CRT workforce and assist CRTs to develop their skills and experience, the prime responsibility rests with DEECD as use of casual teachers is a statewide issue.

Findings

- Few schools support CRTs to participate in professional development activities or provide performance feedback.

- DEECD’s Professional Learning Support Initiative has had limited success in supporting CRT learning. Funding is not effectively targeted and often left unspent.

- Many CRTs cannot access important resources and learning opportunities as schools have not provided them with access to DEECD’s Edumail and Ultranet systems.

- Many schools do not have adequate processes to confirm the identities of CRTs, their registration status and whether they meet policy requirements.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- identify opportunities at a regional level for CRTs to participate in school-based professional development activities

- review the Professional Learning Support Initiative to better target funding and improve CRT quality

- further reinforce with schools that they should provide access to Edumail and the Ultranet for frequently employed CRTs.

3.1 Introduction

Quality teaching should be expected from all teachers, not just those in ongoing positions. When engaged by schools, casual relief teachers (CRT) should be effective in advancing the learning of students.

CRTs account for an estimated 12 per cent of the entire teacher workforce in Victoria and the number employed by government schools has increased by 36 per cent since 2000. Thus, the number of students being exposed to CRTs has also increased significantly.

It is important that CRTs are supported to develop and maintain their professional teaching skills through regular exposure to modern teaching methods and to high quality and relevant professional development.

3.2 Conclusion

CRTs play a critical role in the teacher workforce, yet the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) cannot be sure that its schools have access to skilled and experienced CRTs. No-one has assumed responsibility for monitoring the overall quality of the workforce and for supporting its development.

CRTs are not sufficiently supported by DEECD or schools to develop their skills, keep abreast of the current curriculum, or meet the minimum standards to remain registered to teach. It is therefore likely that the quality of CRTs available to schools is not of the standard required for this important role.

Further work and collaboration between schools and DEECD is needed to better understand and manage CRT performance. The quality of CRTs could be enhanced by extending and improving existing initiatives such as the Professional Learning Support Initiative (PLSI) and increasing CRT access to teaching resources.

3.3 Support for casual relief teachers

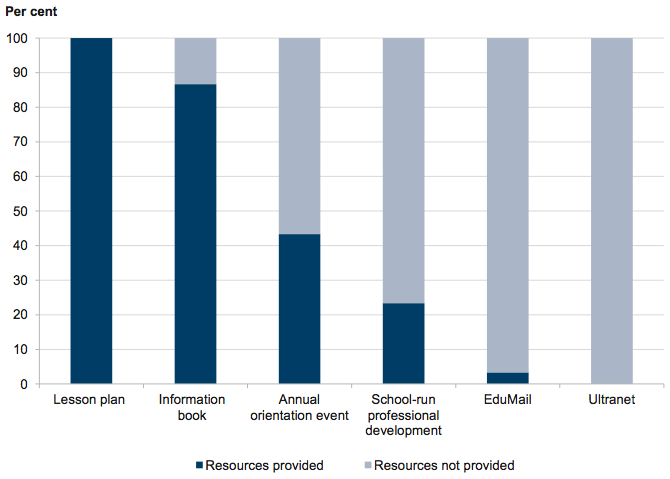

Generally, CRTs do not have access to the same range of resources and support from schools or DEECD that permanent or fixed-term teachers have. For example, without access to Edumail, DEECD’s email and IT system, CRTs cannot readily access current information on education issues, curriculum, and employment and development opportunities. Despite attempts by DEECD to encourage schools to set-up Edumail accounts for regularly used CRTs, none of the audited schools had done so.

Schools can provide CRTs with local access to the Ultranet—DEECD’s secure internet‑based portal for information on government schools and students. Teachers with access to the Ultranet can view teaching plans online, collaborate with other teachers and share best practice information. However, none of the 30 audited schools had provided their CRTs with access and none were aware that they could do so.

All audited schools provided CRTs with a lesson plan. Lesson plans are prepared by classroom teachers and outline the work students should do in each lesson. They are the most critical support to assist CRTs to adequately fulfil their role. However, school‑wide supports such as annual orientation and professional development were less commonly offered. Figure 3A outlines the resources that were made available to CRTs in the audited schools.

Figure 3A

Resources available to casual relief teachers at audited schools

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The case study in Figure 3B examines anaphylaxis training for CRTs, and is indicative of the broader issue facing CRTs who are operating in a highly governed school environment, but without the support that comes from being part of a school. CRTs are expected to maintain the same professional standards as other teachers but are not trained, supported and resourced to do so.

Figure 3B

Case study – Meeting anaphylaxis requirements in schools

In 2008 the government introduced legislation making anaphylaxis training mandatory for all teachers requiring schools to identify students at risk from anaphylaxis to their class teachers.

Anaphylaxis is ‘an acute, life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction, involving the whole body, which is usually bought on by something eaten or injected’. Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency that develops rapidly and can be fatal.

The majority (21 out of 30) of the audited schools provided CRTs with a list and photos of students at risk from anaphylaxis or other medical and behavioural conditions. In nine schools no information was provided, however, the schools expected that CRTs would check the staff notice board and contact office staff should an incident occur. This approach does not comply with the anaphylaxis legislative requirements.

Given that most anaphylaxis training is delivered by schools to their permanent and fixed‑term staff only, it is unlikely that CRTs will have had sufficient and up-to-date anaphylaxis training. None of the audited schools checked whether the CRTs they used had attended anaphylaxis training and DEECD does not know how many or which CRTs have done anaphylaxis training. DEECD expects schools to provide anaphylaxis training to CRTs and therefore anaphylaxis training for CRTs is no longer funded through the PLSI.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

3.4 Professional development for casual relief teachers

Ongoing professional development is essential for teachers to keep abreast of the curriculum and teaching pedagogy. Also, to remain registered, teachers have to complete a minimum of 20 hours of recognised professional development (for example training courses, professional reading or working groups) in the last year. Neither the Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT), DEECD, nor schools comprehensively and consistently monitor and report on the quality or type of professional development undertaken by practicing teachers or CRTs working in government schools. As a consequence, DEECD is not in a position to make informed decisions about the need to support CRTs, the types of support needed and the most effective ways to deliver that support.

3.4.1 Casual relief teacher networks

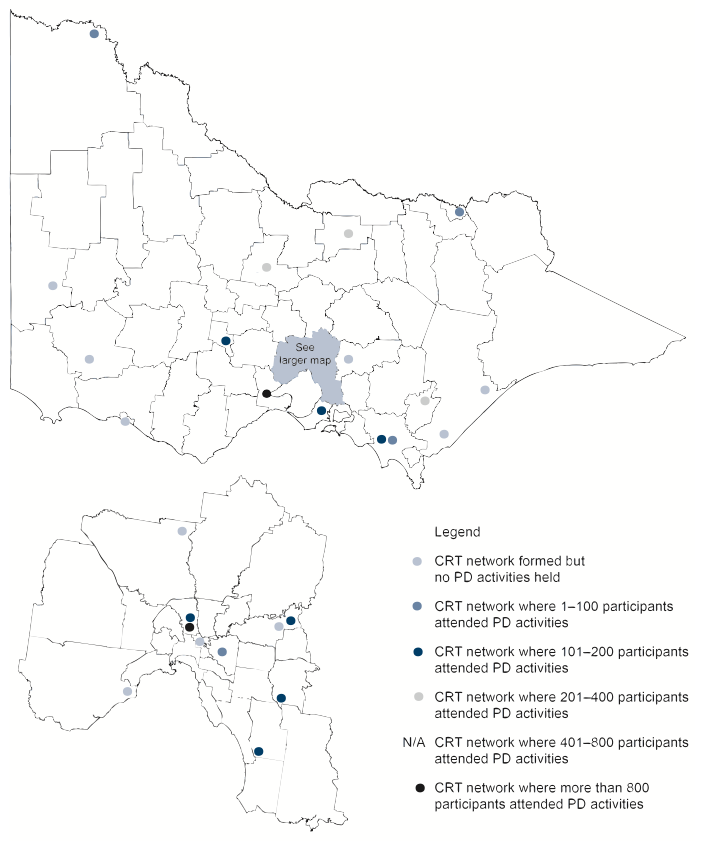

Local CRT networks have been established in some local government areas (LGAs) across the state. These networks are set up and run by volunteer CRTs and are recognised and supported by VIT. Networks are a way for CRTs to meet regularly, share information and knowledge, and participate in professional development activities.

Sixteen CRT networks were established in the 2010–11 financial year and there are now 26 CRT networks across Victoria—most in and around major population centres. The number of networks is increasing with several established in some of the more remote areas of the state such as the Mildura, Horsham and Wellington LGAs.

DEECD funds these networks to assist CRTs to participate in professional development activities. This program is called the Professional Learning Support Initiative.

Figure 3C shows the location of the CRT networks in Victoria and the number of participants in PLSI funded professional development activities during 2010.

Figure 3C

Location of casual relief teacher networks in Victoria

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on Victorian Institute of Teaching data.

3.4.2 Professional Learning Support Initiative

DEECD developed PLSI in 2010 to support CRTs to engage in high-quality professional development programs. It includes a mix of direct funding to support professional development, guidelines for schools to support CRTs, and web-based learning resources for CRTs.

While DEECD has developed significant web-based resources for CRTs, linked to the VIT website, few of the audited schools provided professional development support for CRTs. Only one of the 30 audited schools (three per cent) regularly invited CRTs to school professional development activities.

Schools advised that some CRTs attended school-run professional development activities, but they were only the CRTs who were well known to them and who were working at the school when the activity was scheduled. Schools considered that it was the CRTs responsibility to source and request access to professional development activities. Schools do not pay CRTs to attend professional development activities.

Funding to support casual relief teacher professional development

There is not enough funding or delivery mechanisms to support all CRTs through the PLSI at this time. DEECD distributes funds to selected schools in each region based on a formula that considers geographic size, location and estimated number of CRTs in the region. However, because DEECD does not know how many CRTs there are, or where they are located, the funding is not well targeted.

As the program is only delivered through known CRT networks, its coverage is limited to those areas where volunteers have established such networks. DEECD does not reimburse CRTs for professional development undertaken outside CRT networks.

Since the program started in 2010, DEECD has provided $930 000 to CRT Networks to fund professional development activities. PLSI funds can be used to pay for expenses such as facilitators or venue hire, but cannot be used to pay CRTs to attend the professional development activity. This is in contrast with permanent teacher who undertake professional development within their paid work hours. Funded professional development activities must meet the following criteria:

- related to improving teacher classroom instruction

- deemed by DEECD to be at a reasonable cost

- not provided to an individual or organisation that has a responsibility for, or benefits from, the work of CRTs such as CRT agencies.

In 2010–11, CRT networks received $480 000, but only spent 44 per cent of the funding ($211 000). While two networks spent $132 000, collectively the remaining networks only spent 22 per cent of their allocated funding ($79 000). Unspent funding is rolled over from one year to the next.

CRT Networks report quarterly to DEECD on the professional development activities delivered and the number of CRTs who attended. More than 120 professional development activities were funded through the PLSI in 2010–11 and 4 326 CRTs attended these events. The most popular events were on classroom behaviour management.

DEECD has not evaluated the effectiveness of the PLSI or done any work to understand how it can assess the effectiveness of the program in the future. It also does not collate information about the number of CRTs in networks, where, or how frequently they work.

3.5 Performance management

While CRTs can work for any school, be it government, independent or Catholic, DEECD has a vested interest in making sure that the 1 539 government schools can access a pool of high-quality CRTs. DEECD is also responsible for the general success of the entire school education system, not just government schools.

It is therefore important that DEECD monitors and understands the CRT workforce and takes action to improve CRT skills when needed. It currently does not play a role in this and could do more to encourage or require schools to evaluate and provide feedback in a timely way to regularly used CRTs.

CRTs are not subject to any systematic performance management or performance planning system. Schools do not include CRTs in their teacher performance development programs and if schools perceive CRTs to be underperforming they simply do not employ them again.

Consistent with this was the view given by many audited schools that CRTs are ‘babysitting’ students until the regular teacher returns. Perceptions of performance were heavily focused on the CRT’s ability to keep the class ‘under control’.

Across schools, assessment of CRT performance is often passed on by word‑of‑mouth. Audited schools stated that this was an effective way to make sure CRTs of poor quality were not regularly used. This approach, however, does not address the causes of poor performance and may not be fair to individual CRTs who are not being given an opportunity to develop their skills and capabilities. It is also counter to the principles of the Performance Development and Culture framework implemented in schools to support and develop teachers.

It is likely that CRTs who might otherwise have made a valuable contribution to the school system will exit the profession unless they are supported to develop their skills and maintain their professional registration.

3.6 Registration of casual relief teachers

Schools may only engage a CRT who is registered with, or has been granted permission to teach, by VIT. Prior to 2011, VIT registration was renewed every five years, but as current registrations expire they are now renewed annually.

VIT lists registered teachers on its website, provides registration details to DEECD for use in their central payroll system, and provides teachers with a registration card.

DEECD uses its central payroll system to inform schools when teacher registration renewals are due. However, CRTs are paid locally by schools and school payroll systems do not have access to this information.

Therefore, schools need to manually check that CRTs are properly registered. In practice, this usually involves taking a copy of their current registration card. Audited schools commonly failed to check:

- CRT registration upon engagement, either by checking the VIT register or asking to see the VIT registration card

- the currency of registration of CRTs they have previously used

- the identity of a CRT using photographic identification such as a driver’s licence

- whether CRTs meet other obligations of the school such as having appropriate anaphylaxis training.

Failure to check VIT registration is a recurring problem which is repeatedly raised during DEECD’s financial audits of school councils.

The move to annual teacher registration should help schools confirm the registration of their permanent teachers and regular CRTs more efficiently. However, the move to annual registration will also increase the likelihood that a CRT’s registration may have expired and therefore, schools will need to adopt a more regular and systematic approach to checking registrations.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development should:

- identify opportunities at a regional level for CRTs to participate in school-based professional development activities

- review the Professional Learning Support Initiative to better target funding and improve CRT quality

- further reinforce with schools that they should provide access to Edumail and the Ultranet for frequently employed CRTs.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development with a request for submissions or comments.

The submission and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.