Correctional Services for People with Intellectual Disability or an Acquired Brain Injury

Audit snapshot

What we examined

We examined if the corrections system meets the needs of people with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. We audited the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH).

Why this is important

Prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury are over represented in the corrections system.

In 2018 the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimated that 4.3 per cent of the general population have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

A DJCS study in 2011 estimated that 42 per cent of male prisoners and 33 per cent of female prisoners had an acquired brain injury. In 2023 those with intellectual disability made up 4.4 per cent of prisoners.

These prisoners have a history of returning to prison more often. So, it is important they get the support to:

- be safe in prison

- prepare them for life back in the community.

What we concluded

The corrections system does not fully meet the needs of people with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

DJCS does not know how many prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury and, of these, how many require specialised support.

Both DJCS and DFFH have long waiting lists for programs and not enough specialised beds. So some prisoners will continue to miss out on services that could reduce their risk of reoffending.

What we recommended

We made 13 recommendations to DJCS, including:

- 9 about improving its processes

- 3 about monitoring and overseeing specialised services

- one about advising the government about the demand for some services.

We made 2 recommendations to DFFH including:

- advising the government about the demand for its residential treatment service

- evaluating its services.

Video presentation

Key facts

*The 48 beds for women are also for prisoners with other types of disability.

Source: VAGO.

Our recommendations

We made 15 recommendations to address 3 issues. The relevant agencies have accepted our recommendations or accepted them in principle.

| Key issues and corresponding recommendations | Agency response(s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: The Department of Justice and Community Safety does not adequately govern its services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury | ||||||

|

Department of Justice and Community Safety

|

1 |

Develops governance arrangements, including monitoring and assurance processes to coordinate its services and support for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury (see sections 2 and 3). |

Accepted |

|||

|

2 |

Regularly evaluates reoffending rates for:

|

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

3 |

Identifies and monitors the demand for specialised accommodation for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury (see Section 2). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

4 |

Develops criteria to prioritise which prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury should:

|

Accepted |

||||

|

5 |

Regularly reviews course materials for adapted offending behaviour programs to make sure they are up to date (see Section 3). |

Accepted |

||||

|

6 |

Analyses the needs of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury to assess if it should develop more adapted offending behaviour programs (see Section 3). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

7 |

Expands adapted offending behaviour programs to provide the best opportunity for prisoners to attend before their release date or the date they are eligible for parole (see Section 3). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

8 |

Advises the government about the demand for its services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury, including:

|

Accepted |

||||

| Issue: The Department of Justice and Community Safety does not know if it meets its own requirements to support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury | ||||||

|

Department of Justice and Community Safety |

9 |

Monitors if prisons comply with the Corrections Victoria Deputy Commissioner’s Instruction: 2.08 Prisoners with Disability (see sections 2 and 3). |

Accepted in principle |

|||

|

10 |

Develops a mandatory questionnaire or tool for prison staff to identify all incoming prisoners who may have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury (see Section 2). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

11 |

Rolls out the existing disability training for prison officers on how to identify and support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. The Department of Justice and Community Safety should:

|

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

12 |

Makes sure that the Prisoner Information Management System and the Corrections Victoria Intervention Management System have consistent and accurate information about prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury (see Section 2). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

|

13 |

Sets timeframes and a monitoring process for updating flags for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury in the Prisoner Information Management System and the Corrections Victoria Intervention Management System (see Section 2). |

Accepted in principle |

||||

| Issue: The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing does not have enough specialised beds for people with intellectual disability | ||||||

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

14 |

Advises the government about the demand for specialised beds in its residential treatment facilities, including:

|

Accepted |

|||

|

15 |

Regularly and comprehensively evaluates the Forensic Disability Service and Complex Needs Service (see Section 3). |

Accepted |

||||

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. The chapters detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

Intellectual disability and an acquired brain injury are different forms of cognitive impairment. We only looked at intellectual disability and acquired brain injury in this audit to exclude certain forms of cognitive impairment, such as dementia.

Cognitive impairments can affect a person's:

- thinking skills

- memory

- reasoning

- comprehension

- communication

- learning ability.

The impact of intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury differs for each person.

Prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury may need adjusted services and accommodation to make sure they:

- are safe in prison

- have the best chance of rehabilitation.

These prisoners are held in Victoria's 14 prisons.

Corrections Victoria, a business unit of the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS), manages specialised beds and programs for people with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. It has 94 beds across the entire prison system. Not all prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury need a specialised bed. DJCS provides services and programs at all prisons.

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) also has 19 beds in specialised facilities for offenders with intellectual disability. People held in DFFH's residential facilities are referred to as residents.

Residents need to meet strict criteria under legislation for a judge to sentence them to a DFFH specialised facility.

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 3 key areas:

|

1 |

DJCS does not adequately govern its services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. |

|

2 |

DJCS does not know if it meets its own requirements to support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. |

|

3 |

DFFH does not have enough beds for people with intellectual disability. |

Key finding 1: DJCS does not adequately govern its services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

Overseeing services

DJCS does not have centralised governance arrangements to coordinate its services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

Instead, different teams at DJCS and Corrections Victoria are responsible for different things, such as prisoner placements and offending behaviour programs. This means:

- prisons do not deliver services consistently

- some services are under-resourced

- prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury do not have an equal chance of accessing support.

Specialised prisoner accommodation

Not all prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury need a specialised bed. But DJCS acknowledges that the number of prisoners who need them exceeds the number of beds.

DJCS does not know the full extent of this demand because it does not have:

- accurate data on the number of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

- a waiting list for these beds.

This means that most of these prisoners are in mainstream accommodation where they:

- might be more vulnerable

- have limited access to specialised support.

DJCS has no clear process for prioritising and placing prisoners in specialised beds.

Adapted offending behaviour programs

DJCS has adapted 2 of its offending behaviour programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. These programs are for:

- violent offenders

- sexual offenders.

DJCS has not reviewed or updated these programs for over 7 years.

This means they might not be up to date and reflect best-practice approaches to supporting people with disability.

There are no targeted offending behaviour programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury who commit other types of offences.

Waiting lists for adapted offending behaviour programs

DJCS has waiting lists for its adapted offending behaviour programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

If a prisoner does not finish their offending behaviour program it may negatively affect their chance of getting parole. As of 31 March 2023:

|

There were … |

This means that … |

|---|---|

|

19 prisoners on the waiting list who will not finish their program before their release date. |

|

|

38 prisoners had passed their earliest eligibility for parole date but had not started their program. |

|

Benefits of support programs

DJCS has 2 services that help prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

These programs are:

- the Prison Disability Support Initiative (PDSI), which DJCS runs at all prisons

- the Disability and Complex Needs Service (DCNS), which is a trial at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre.

The PDSI provides a range of services. It has helped prisoners access over $4 million in National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) support packages. These packages support prisoners when they go back into the community.

DJCS told us that these programs have helped prison officers better support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

But demand for the programs exceeds the resources DJCS has to deliver them.

Demand for support programs

In some cases, prisoners are released before they can access DJCS's PDSI program. This is because there are not enough places.

This means that some prisoners will not:

- have access to support programs while in prison

- get help applying for NDIS support before they are released.

Expanding these programs would help meet the demand. The disability and complex needs initiative has funding to extend its trial.

In 2022–23 DJCS submitted a Budget bid to increase the PDSI's funding and resources. The bid said that an expanded PDSI would:

- help reduce the risk of reoffending

- assist prisoners to reintegrate back into the community.

But this bid did not include:

- the waiting lists for these programs

- how many prisoners are missing out on services.

This Budget bid was partially successful and the PDSI has continued to receive the same funding.

Evaluating services

It is too early to tell if the PDSI and DCNS are achieving their long-term outcomes, including reducing reoffending. This is because the PDSI started in 2021 and the DCNS started in 2020.

This means DJCS does not know:

- if the services are working

- how it can improve them.

DJCS is drafting a plan to evaluate its offending behaviour programs. DJCS told us that this might include assessing if the programs are reducing reoffending.

But it has not finished this plan and its management have not approved it.

Key finding 2: DJCS does not know if it meets its own requirements to support prisoners with disability

Making sure prison services are consistent

The Deputy Commissioner of Corrections Victoria issues instructions to make sure public prisons run consistently.

Corrections Victoria Deputy Commissioner’s Instruction: 2.08 Prisoners with Disability (Instruction 2.08) says a prison's general manager must make sure:

- the prison has a process to identify if prisoners have a disability

- the prison refers these prisoners to appropriate services

- the prison gives prisoners with disability reasonable adjustments

- prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury have access to adapted education, training and treatment services

- the prison accommodates prisoners with a disability in a safe and secure environment

- information about a prisoner's disability is recorded in the prison's systems.

Reasonable adjustments

Reasonable adjustments are changes made to services, programs or activities to meet the needs of people with disability and allow them to participate.

For example, prison staff could deliver a training program at a slower pace and use simplified reading materials for some prisoners with intellectual disability.

Monitoring if prisons follow Instruction 2.08

DJCS does not monitor if prisons follow Instruction 2.08.

This means that DJCS does not know if prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury get the support they need.

Identifying prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

DJCS does not have a mandatory screening tool or questionnaire to identify if prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

To be able to achieve the government's priority goals of prisoner rehabilitation and reduce reoffending, DJCS proposed to:

- introduce a screening tool to identify prisoners with cognitive impairment

- adapt existing programs to meet the needs of prisoners with cognitive impairment

- expand alcohol and other drug treatment services in prison.

DJCS sought additional funding in 2017–18 to introduce a screening tool but this was unsuccessful. The Budget bid noted that certain groups of prisoners, including those with cognitive impairment are:

- over-represented

- not suitably identified on entry into prison

- more likely to reoffend when released from prison.

Training

Some prison officers get training on how to:

- recognise the signs of cognitive impairment

- adapt activities to prisoners' needs.

But this training is limited and not mandatory.

This means that some prisoners will not:

- get extra support when they enter prison

- get the right support and treatment in prison.

This may affect their:

- safety and wellbeing in prison

- chances of rehabilitation

- return to the community.

Reasonable adjustments

Outside of dedicated programs or specialised beds, prisons can make reasonable adjustments for prisoners on a case-by-case basis.

But this depends on each prison officer's judgement and experience because there is no mandatory training.

This means the quality and usefulness of reasonable adjustments varies across the corrections system.

Information about prisoners

Prisons use 2 main information technology (IT) systems to record information about a prisoner's intellectual disability or acquired brain injury.

But:

- these systems do not interface with each other and the data is not integrated

- the numbers of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury are different in these systems.

This means that DJCS does not know:

- how many prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

- of these prisoners, how many need specialised support or adapted activities.

Updating a prisoner's information

DJCS's process for updating information about a prisoner's disability in its main IT system is inefficient. The PDSI team is responsible for updating a prisoner's intellectual disability or acquired brain injury status in this system. The PDSI team only has one staff member with the clinical qualifications and access to its IT system to update the flags.

Prison staff must forward information about a prisoner's disability to this DJCS staff member and wait for this information to be updated.

Prison staff told us it can take up to 6 months to update a prisoner's information on the system. However, DJCS is unable to quantify these delays because it does not collect this information.

The delays mean that some prison staff may not have up-to-date information about prisoners. These prisoners may miss out on adjusted services and accommodation.

Key finding 3: DFFH does not have enough beds for people with intellectual disability

Forensic disability service

DFFH runs the forensic disability service.

The service gives people with disability specialised support and treatment to reduce the risk of them reoffending.

DFFH runs the service through 2 secure residential treatment facilities. These facilities have beds for up to 19 men.

These facilities are different from prison. Residents often live in a house with shared living areas. They can access specialised services, including:

- clinical services, like psychology sessions

- support to build life skills.

Residential treatment facilities

DFFH regularly monitors supply and demand for beds in its facilities.

In 2022–23 DFFH sought additional funding from government to increase the number of beds by 20 to meet current and future demand. It based its Budget bid on detailed forecasting.

But the bid was not successful. This means that most offenders go into mainstream prisons where they may not get the clinical support they need to:

- reduce their risk of reoffending

- live independently.

1. Audit context

In Victoria, people with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury are over-represented in the prison population. Prisons need to give these prisoners the right support to make sure they are safe and have the best chance of rehabilitation.

Intellectual disability and acquired brain injury

What is intellectual disability?

The Disability Act 2006 defines intellectual disability as a person having significant:

- sub-average general intellectual functioning

- deficits in learning and performing everyday tasks, like cooking, shopping and cleaning.

These need to be present before a person turns 18 years old.

What is an acquired brain injury?

An acquired brain injury is caused by injury to a person's brain. It can happen at any time during their life. An acquired brain injury can:

- affect a person's ability to learn and think

- make it hard for a person to manage their behaviour and emotions.

Many things can cause an acquired brain injury, including:

- a head injury

- drugs or alcohol

- a stroke

- lack of oxygen to the brain.

The impact of an acquired brain injury can vary depending on which part of the brain was injured.

Diagnosing intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

A specialist needs to diagnose intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. A psychologist usually does the assessment. A specialist will undertake tests on a person's ability including:

- intelligence testing

- cognitive ability

- daily functioning.

The specialist will also review a patient's files, including their:

- medical history

- developmental history

- academic history.

These assessments can be long, complex and expensive.

Victoria's prison system

The purpose of prison

A court can sentence a person to prison if it finds them guilty of committing a crime.

The state has an opportunity to rehabilitate a person when they are in prison by offering:

- educational courses

- offending behaviour programs

- help going back into the community.

The state can also put people in prison when they are waiting for their trial or sentencing.

But these people do not have access to the same rehabilitation services.

Prison operating environment

Prison staff work in a complex environment that changes daily. Some factors they need to consider are:

- prisoners' complex needs, including disability, medical, mental health or drug and alcohol issues

- movements of prisoners across the system

- the need to balance safety and security with offering programs and services to reduce a prisoner's risk of reoffending.

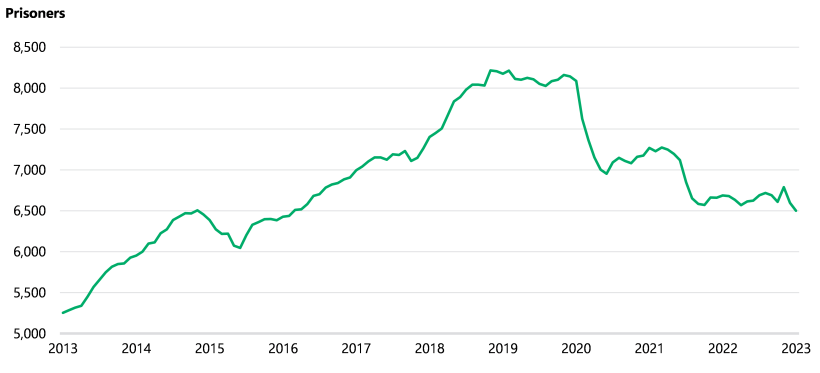

Victoria's prison population

Victoria's prison population has increased by 24 per cent since March 2013, in comparison to a 17 per cent growth in the general population.

On 31 March 2023 there were 6,501 people in prison in Victoria, including:

- 6,186 men

- 315 women.

Of these people, 2,641 had yet to be sentenced. This includes prisoners who are:

- unconvicted

- convicted but awaiting sentencing

- pending deportation.

Figure 1: Number of prisoners in Victoria between March 2013 and March 2023

Source: DJCS data.

Number of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

People with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury are over-represented in Victorian prisons.

The exact number is not known. But DJCS's research and data found that:

- in 2023 prisoners with intellectual disability made up 4.4 per cent of the prison population. This is an increase from 1.8 per cent in 2005

- between 2007 and 2009 DJCS tested 196 prisoners and found 42 per cent of male prisoners and 33 per cent of female prisoners had an acquired brain injury. Of these prisoners:

- 6 per cent of men had a severe acquired brain injury

- 7 per cent of women had a severe acquired brain injury.

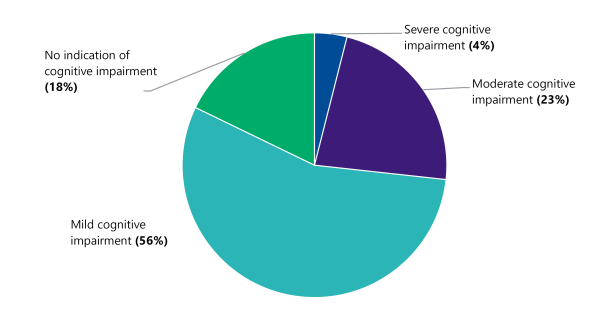

DJCS also did a research project in 2020 on sentenced and unsentenced prisoners. It assessed participants who:

- prison staff believed had a cognitive impairment

- were flagged in a DJCS system as having intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

- referred themselves because they thought they needed extra support in prison.

The study had 136 participants. It was done to show the need for better identification processes. Figure 2 shows the results from this project.

Figure 2: Findings from DJCS's research project in 2020 on prisoners with a cognitive impairment

Note: Numbers have been rounded.

Source: DJCS research project.

DJCS's role and services

Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria is a business unit of DJCS. It is responsible for:

- managing Victoria's 14 prisons and one transition centre

- setting strategies, policies and standards on how prisons should run

- making and delivering programs to rehabilitate prisoners.

DJCS's specialised beds

DJCS has 94 specialised beds for prisoners with a cognitive impairment. There are:

- 46 for men

- 48 for women*.

These beds provide:

- a safe and secure environment for these prisoners

- additional support for these prisoners.

DJCS is responsible for placing prisoners into these beds. Not all prisoners with intellectual disability or acquired brain injury require one of these beds.

*The 48 beds for women are also for prisoners with other types of disability.

DJCS's services

DJCS runs services to help prisoners with disabilities, including:

- the PDSI

- the DCNS.

Prisoners do not need to be housed in specialised beds to access these services.

Offending behaviour programs

Forensic Intervention Services is a business unit in DJCS. It runs offending behaviour programs in prisons and the community.

These programs give prisoners the opportunity to:

- change their behaviour

- reduce their risk of reoffending.

DJCS runs 2 intervention programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury:

- one for violent offenders

- one for sex offenders.

DJCS runs these programs at a slower pace. It takes prisoners up to one year to finish them.

DJCS also runs individual programs for prisoners who cannot take part in groups.

Prison Disability Support Initiative

The PDSI is DJCS's statewide disability service. It provides support to all prisoners with a suspected or confirmed cognitive disability who have a functional deficit that requires support that is not available through other services.

The PDSI has 5 streams for prisoners and the prison officers who manage them:

|

Stream |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Stream 1 |

Helping prisoners access support services, including the NDIS |

|

Stream 2 |

Diagnosing intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury |

|

Stream 3 |

Helping prison officers learn how to:

|

|

Stream 4 |

Training and supporting prison staff |

|

Stream 5 |

Providing therapeutic intervention to:

|

DJCS introduced the PDSI in July 2021 for a one-year trial.

In May 2022, the government funded the PDSI for a further 4 years.

Disability and Complex Needs Service

The DCNS supports women with disabilities and/or complex needs. This includes women with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

DJCS runs the DCNS at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre. The service:

- helps prison staff meet the needs of prisoners with a disability

- gives prisoners occupational therapy, behaviour support or diversion therapy

- helps prisoners apply for the NDIS.

DJCS started trialling the DCNS in July 2020.

The government has extended the trial until June 2024.

DFFH's role and services

Specialised beds for people with intellectual disability

DFFH runs the forensic residential service.

This program gives residents with intellectual disability specialised clinical and behavioural support.

DFFH runs the program at 2 residential treatment facilities outside of prison. It has 19 beds across these facilities. DFFH’s facilities are for men with intellectual disability.

A person is admitted to a residential treatment facility via strict criteria in the Disability Act 2006. DFFH's secretary must be satisfied that:

- the person has intellectual disability

- the person has been found guilty of a serious offence

- the person has a serious risk of being violent to another person

- DFFH has considered all less-restrictive options (such as getting treatment in the community) and they are not suitable

- the facility has suitable treatment services for the person

- a court has made an appropriate legislative order.

DFFH usually decides if a person is eligible when a court sentences them.

It can house a resident in a residential treatment facility for up to 5 years.

Corrections Victoria can apply to transfer a prisoner to these facilities under the Disability Act 2006. But it has only done this once.

Disability justice coordination

DFFH runs the disability justice coordination service in:

- the community

- prisons

- residential treatment facilities.

The service supports people to understand the justice system and the sentence or order they are on. It also coordinates access to services, such as the NDIS, to improve their quality of life and support community safety.

Only people with access to DFFH's disability services can use it.

Prison databases

DJCS's prison databases

DJCS has 5 databases to record information about a prisoner's intellectual disability or acquired brain injury.

Staff usually use:

- Prisoner Information Management System (PIMS)

- Corrections Victoria Intervention Management System (CVIMS).

PIMS

PIMS manages information about prisoners in public and private prisons across Victoria.

It records key information, including a prisoner's:

- personal details

- history in prison

- current prison

- warrants

- incidents

- security classification.

PIMS also has check boxes to record if a prisoner has intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

CVIMS

CVIMS manages information about programs and clinical assessments delivered by:

- DJCS's Forensic Intervention Services

- private prisons

- externally contracted providers

- alcohol and other drug program providers.

CVIMS allows staff to manage, view and store:

- referrals for programs

- assessments

- completed interventions

- case notes.

It also allows staff to:

- monitor service delivery and waiting lists

- record if a prisoner has intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

CVIMS does not have information about all prisoners.

2. Entering prison

DJCS does not have a comprehensive process to identify if new prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

If DJCS does not identify one, the prisoner will not get specialised support.

DJCS and DFFH do not have enough specialised accommodation for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. This affects these prisoners' safety and rehabilitation.

DJCS does not know how many prisoners need specialised support

Identifying prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

DJCS does not know how many prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

It also does not know how many prisoners need specialised support or adapted programs.

This is because DJCS does not:

- have a mandatory screening tool to assess new prisoners' needs

- train prison officers on how to recognise signs of intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

- have accurate information in its IT systems.

DJCS has told us that there are difficulties in identifying a prisoner with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury because of:

- the lack of a diagnostic screening tool

- the long, complex and expensive assessments.

Screening new prisoners

Prison officers do not have a mandatory screening tool to identify if a new prisoner has signs that they may have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

This means some prisoners may miss out on:

- specialised accommodation, which helps keep them safe

- rehabilitation programs that help them go back into the community

- the opportunity to have their daily prison activities and obligations changed to meet their needs.

During the current process, the prison officer:

- reviews information about the new prisoner

- asks them questions to consider if they have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

These questions include:

- 'Did you go to a special school?'

- 'Do you receive a disability pension?'

Some prisoners might not want to disclose that they have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

When prisoners first arrive at prison, it may not be the best time to ask detailed questions to identify signs of intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. But asking new prisoners about their needs is an important step towards making sure they get the right support. Currently, DJCS does not routinely do this.

2017–18 Budget bid

DJCS submitted a Budget bid in 2017–18 to introduce a screening tool to help prison officers identify new prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

But this bid was not successful.

PDSI and DCNS questionnaires

The PDSI has developed a questionnaire to help prison officers identify the signs of intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

The DCNS also made a similar form.

In the absence of a screening tool, the introduction of these forms are positive developments in:

- identifying prisoners who potentially have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury

- educating prison officers about prisoners' disability needs.

Prison officers can also use these forms to refer new prisoners to the PDSI and DCNS for further screening.

But they are not mandatory so not all prisons use them.

We reviewed 40 prisoner files and found this form on one file.

Training prison officers

Prison officers cannot formally diagnose someone with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

But they can be trained to:

- recognise the signs

- decide if a prisoner needs extra support.

The PDSI has started running cognitive impairment awareness training for interested prison officers.

It has run this training 13 times across different prisons. But it is not mandatory. DJCS does not consistently record attendance at this training.

The DCNS is organising cognitive impairment training at female prisons (Dame Phyllis Frost Centre and Tarrengower Prison). This is not scheduled until June 2023.

DJCS does not run any mandatory training for prison officers.

|

Without mandatory training, prison officers … |

This means … |

|---|---|

|

rely on their experience to identify if prisoners have intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. |

their approaches are not consistent. |

|

might not recognise the signs of intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury. |

they will not refer these prisoners to specialised programs and support. |

DJCS's IT systems

DCJS does not have a single source of information about prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

It has 5 systems where staff can record whether a prisoner has intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

As Figure 3 shows, we examined CVIMS and PIMS and found that they have different numbers of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

Figure 3: Number of prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury in PIMS and CVIMS as of 21 December 2022

| Disability | Number in PIMS | Number in CVIMS |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual disability | 285 | 293 |

| Acquired brain injury | 57 | 105 |

| Total | 342* | 398* |

*This includes some prisoners who have both intellectual disability and an acquired brain injury.

Source: VAGO based on DJCS data.

These systems do not interface with each other and the data is not integrated.

DJCS told us that:

- PIMS records essential information about all prisoners

- CVIMS does not capture all prisoners and only holds information about prisoners engaging in clinical programs. We would expect that the number of prisoners in PIMS would be higher than CVIMS.

We found examples where a prisoner with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury was recorded in CVIMS but not PIMS. In particular, we found:

- 49 prisoners with intellectual disability in CVIMS but not PIMS

- 55 prisoners with an acquired brain injury in CVIMS but not PIMS.

CVIMS and PIMS are managed by two separate teams in DJCS and there is no system integration between these IT systems.

Recording information in PIMS

DJCS does not have an efficient process for updating information about a prisoner's disability in PIMS.

The PDSI team is responsible for updating the flags. This team has only one staff member with the clinical qualifications and level of access to update a prisoner's intellectual disability or acquired brain injury status.

As a result, prison staff must forward information about a prisoner's disability to this DJCS staff member and wait for this information to be updated.

Prison staff told us it can take up to 6 months to update a prisoner's information. However, DJCS are unable to quantify these delays as they do not collect this information.

There are also delays in getting a prisoner's medical information. This is because DJCS staff have to find this information from public hospitals or doctors and DJCS must comply with privacy and health legislation.

This means that some prison staff may not have up-to-date information about prisoners. These prisoners may miss out on adjusted services and accommodation.

DJCS does not know how many specialised beds it needs

Demand for specialised beds

DJCS has 94 beds in specialised accommodation for prisoners with a cognitive impairment.

As Figure 3 shows, there are at least 398 prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

Not all of these prisoners would need a specialised bed. But DJCS needs to know how many do need them so it can manage demand.

Managing demand

DJCS does not know how many prisoners need specialised accommodation.

This is because it does not:

- know which prisoners need it

- have a waiting list to manage demand.

DJCS does not have any plans to increase the number of specialised beds.

Supporting staff in mainstream units

Prison staff support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury in mainstream units when there are not enough specialised beds.

We saw examples in prisoner files where these staff were supporting them with reasonable adjustments.

Prison staff also told us they advocate for these prisoners to get specialised beds.

DFFH does not have enough specialised beds

Demand for specialised beds

DFFH has had 19 beds in its residential treatment facilities since 2002.

Victoria’s prison population has almost doubled from 3,608 prisoners in 2002 to 6,501 in 2023.

Based on this increase, we expect the demand for these beds would have gone up.

DFFH’s modelling shows that it needs more than 15 extra beds to meet the current demand.

It expects this gap to increase to more than 40 beds by 2028–29.

Access to specialised beds

DFFH told us that not all people who could benefit from its residential treatment facilities can get a bed.

People who miss out live in mainstream prisons or may be released into the community where they may not get:

- the clinical support they need

- the best chance at rehabilitation.

For example, DFFH has only had between 2 and 4 beds available between March 2022 and March 2023.

DFFH told us that it leaves some beds vacant because:

- some residents cannot share their living space (normally a unit or small house)

- a person must meet strict criteria to access a bed.

The Disability Act 2006 sets the eligibility criteria for DFFH's facilities. Since January 2020, only 7 out of 28 people referred to them were eligible. DFFH have told us that there have been no rejections because of a lack of vacancies.

DFFH recently introduced a forensic disability prison transition advisor.

This person will assess if there are prisoners who meet the eligibility criteria.

DFFH expects that this will increase the number of referrals to these facilities.

2022–23 Budget bid

DFFH submitted a comprehensive Budget bid in 2022–23 to expand its residential treatment facilities and its community programs for people with intellectual disability who are involved in the criminal justice system. Its Budget bid was supported by data analysis of demand. It also included the avoided costs of expanding its service, which were estimated to be $3.8 million over 10 years by diverting people from reoffending.

Based on its modelling, it asked for an extra 20 beds immediately, including 4 for women. DFFH's Budget bid also sought additional support staff for residential treatment facilities.

But its bid was not successful.

Who specialised beds are for

DFFH does not have any specialised beds available for:

- women

- men with an acquired brain injury.

This means that these prisoners do not have access to DFFH's specialised services to help them go back into the community and live independently.

3. Services and support in prison

DJCS and DFFH offer services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

Long waiting lists for these programs mean some prisoners will not access a service before they leave prison.

These prisoners miss out on some of the rehabilitative opportunities prisons can provide.

Not all prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury will complete DJCS's adapted offending behaviour programs

Waiting lists for offender behaviour programs

There is a waiting list for DJCS's adapted offending behaviour programs.

As Figure 4 shows, prisoners on this list need to go through different stages to access these programs. This can take a long time.

This means that some prisoners will not get:

- to finish a program before they leave prison

- the full opportunity for rehabilitation

Figure 4: Prisoners awaiting allocation, review, screening, assessment and treatment for DJCS's adapted offending behaviour programs as of 31 March 2023

| Time remaining until release from prison | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months | 6–12 months | 12–18 months | 18–24 months | 24–36 months | 36+ months | Total | |

| Referral awaiting allocation to queue | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Awaiting pathway review | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Awaiting screening | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Awaiting assessment | 2 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 20 | 73 | 110 |

| Awaiting treatment | 3 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 43 |

| Total | 7 | 12 | 19 | 13 | 28 | 86 | 165 |

Note: Red numbers show the number of prisoners who will not get the right amount of treatment before they leave prison.

Source: VAGO based on DJCS data.

As of 31 March 2023, there were 19 prisoners on the waiting list with less than 12 months until their release date.

Prisoners may take up to 12 months to complete these programs. This means these prisoners will not get the right amount of treatment before they leave prison.

DJCS told us that there are waiting lists for all its offending behaviour programs.

Where DJCS runs offending behaviour programs

DJCS does not run adapted offending behaviour programs at all prisons.

Since 2019, DJCS has run:

- 8 programs for violent offenders across 5 prisons

- 5 programs for sex offenders across 3 prisons.

DJCS told us:

- it runs programs at prisons where there are more prisoners on the waiting list

- it will deliver a program when there are enough prisoners to form a group

- in prisons with insufficient numbers to form a group, it asks prisoners to transfer to other prisons so they can participate

- resourcing challenges and COVID-19 restrictions have reduced the number of sessions it runs.

We reviewed 40 prisoner files and saw 2 cases where a prisoner did not want to transfer to a different prison to participate in these programs.

DJCS staff confirmed that some prisoners do not want to go to a different prison, particularly when it means moving to a higher-security prison.

Case study: A prisoner could not participate in an offending behaviour program due to safety concerns.

In 2018, a prisoner with intellectual disability was referred to DJCS's program for sex offenders.

The prisoner was transferred from Hopkins Correctional Centre (a medium-security prison) to Port Phillip Prison (a maximum-security prison) to participate. This was because at this time, DJCS only ran the adapted version of the program at Port Phillip Prison.

When they arrived at Port Phillip Prison, they had immediate safety concerns.

After a week, they transferred back to Hopkins Correctional Centre because of these concerns.

The prisoner asked if they could do the program at the Hopkins Correctional Centre. But DJCS refused because it only ran the program at Port Phillip Prison at the time.

As a result, the prisoner did not take part in the program.

Source: VAGO based on a prisoner file. Photo from DJCS.

Impact on parole

Some prisoners can apply to the Adult Parole Board to serve the rest of their sentence in the community.

While on parole, a prisoner:

- must meet parole conditions

- is supervised by DJCS.

The Adult Parole Board considers a range of factors when assessing an application. This includes:

- if the prisoner poses a risk to the community

- what offending behaviour programs a prisoner has completed.

As Figure 5 shows, there are:

- 38 prisoners on the waiting list who had passed their earliest eligible date for parole, but had not started their adapted offending behaviour program

- 47 prisoners on the waiting list who may not complete their adapted offending behaviour program before they are eligible to apply for parole.

Figure 5: Number of prisoners on the waiting list for DJCS's adapted offending behaviour programs as of 31 March 2023

| Waiting list stage | Prisoners past their earliest eligibility date for parole | Prisoners who may not complete their full program before they are eligible to apply for parole* |

|---|---|---|

| Referral in progress | 1 | 3 |

| Awaiting screening, assessment and pathway review | 10 | 34 |

| Awaiting treatment | 27 | 10 |

| Total | 38 | 47 |

*Adjusted offending behaviour programs take up to one year to complete. The number of prisoners who may not complete their program is the number of prisoners on the waiting list with less than one year until their parole eligibility date.

Source: VAGO based on DJCS data.

Prisoners can still apply for parole if they have not completed an offending behaviour program. But this can reduce their chance of getting parole.

This is particularly the case when the Adult Parole Board does not believe the prisoner's risk of reoffending can be reduced in other ways. For example, through parole conditions.

In 2021–22, 22 per cent of denied parole applications were not approved because the prisoner had not completed a program.

This included cases where prisoners could not complete one:

- due to factors outside their control

- because they refused to participate.

By not making sure there are enough places in offending behaviour programs, DJCS is not giving prisoners the best opportunity to get parole.

It is also a missed opportunity to keep the community safe by:

- helping prisoners transition back into society

- supervising prisoners through parole conditions, such as reporting to a community corrections officer

- reducing the risk of prisoners reoffending.

DJCS told us there are similar waiting lists and associated issues with parole for all prisoners.

DJCS's programs have benefits, but not all prisoners can access them

Benefits of DJCS's programs

The PDSI and DCNS are positive steps to support prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

For example, the PDSI has helped prisoners access over $4 million in NDIS support packages to help them go back into the community. There are other ways for a prisoner to get assistance to access NDIS support packages.

Prison officers told us that the PDSI helps them support these prisoners by:

- providing strategies to manage challenging behaviour

- helping them to better understand the causes of the behaviour.

But the demand for these programs exceeds DJCS’s resources to deliver them.

This means that some prisoners are released before they can access a program. DJCS told us that short prisoner sentences make it difficult to service all prisoners before they leave prison.

These prisoners might go back into the community without:

- NDIS support

- access to positive behaviour support.

PDSI waiting list

The PDSI had 105 active referrals currently receiving a service in one of the five streams on 31 March 2023. Figure 6 shows the PDSI also has 424 referrals on the waiting list at this date.

Figure 6: Referrals on the PDSI waiting list at 30 September 2022 and 31 March 2023

| Stream | Number of PDSI referrals on the waiting list at 30 September 2022 | Number of PDSI referrals on the waiting list at 31 March 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Accessing support services, including the NDIS | 87 | 151 |

| 2. Specialist clinical assessments | 69 | 143 |

| 3. Positive behaviour change | 13 | 51 |

| 4. Training and support for prison staff | 21 | 53 |

| 5. Therapeutic intervention | N/A* | 26 |

| Total | 190 | 424 |

*Stream 5 was recently introduced so it did not have a waiting list at 30 September 2022.

Source: VAGO based on DJCS.

Case study: Referrals to the PDSI are increasing.

Figure 6 shows the number of referrals on the waiting list for the PDSI has more than doubled between 30 September 2022 and 31 March 2023 to 424.

The waiting list does not include a further 100 referrals that are waiting to be processed and allocated to the list.

Prison staff have told us that as awareness and understanding of the PDSI's services has increased, more referrals are being made. Although it is too early to evaluate the effectiveness of the PDSI, this increase suggests that prison staff view the PDSI as a positive step to improving services for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

The PDSI team is currently testing a tool to triage and prioritise high-priority referrals.

The PDSI manager oversees this waiting list. But they do not report on it for DJCS to oversee. It is important for DJCS to monitor the list so they can understand and respond to demand.

Source: VAGO based on DJCS data and interviews with DJCS staff. Photo from DJCS.

DCNS waiting list

As of 31 March 2023, the DCNS had 6 prisoners on its waiting list.

DJCS only runs the DCNS at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre. So the demand and waiting list is smaller than the PDSI.

The DCNS coordinator manages the waiting list. But they do not report on it for DJCS to oversee.

DJCS got funding in 2021–22 to extend the DCNS trial.

There is a long waiting list for DFFH's services

Waiting list for DFFH’s services

DFFH runs the disability justice coordination service. One element of this service is to help people with access to DFFH's disability services apply for the NDIS.

As of 31 March 2023, there were 603 people using the service.

Of these people, 65 were in prison. The rest were in the community and residential treatment facilities.

Coordinators who run the service can manage approximately 15 participants each. But the demand exceeds the number of available coordinators.

Between March 2022 and March 2023 there were between 5 and 58 people on the waiting list. This includes:

- prisoners

- people in the community

- people in residential treatment facilities.

DFFH did a Budget bid in 2022–23. One part of this bid was to set up a support team for the service. This team would support clients after they leave a residential treatment facility.

But it did not seek funding to:

- meet the program’s future demand

- support prisoners from mainstream prisons go back into the community.

The Budget bid was not successful.

DFFH’s modelling

DFFH’s 2018 modelling showed that 12 per cent of prisoners were eligible for its services. But only 1 per cent of prisoners accessed these services.

This includes its:

- disability justice coordination service

- residential treatment facilities.

As of March 2023, 12 per cent is approximately 780 prisoners.

This means that most prisoners who could benefit from DFFH’s services do not get to use them.

Expanding the services could help DFFH make sure more people:

- are safe in custody

- have access to the NDIS

- have a better chance at not reoffending.

Some prison staff make reasonable adjustments, but this is on an ad hoc basis

Reasonable adjustments in prison

Instruction 2.08 says prisons must give reasonable adjustments to all prisoners who have identified disability needs.

It does not describe how prisons should provide them.

Prison officers make reasonable adjustments on a day-to-day basis to meet the immediate needs of prisoners with confirmed or suspected intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

We saw the following examples of reasonable adjustments across the 40 prisoner files we reviewed:

- a prisoner completed group programs individually

- a prisoner was given fewer monthly goals, with an example of a goal being participating in a prison training program

- prison officers, with help from the DCNS, creating an activity schedule to help a prisoner stay focused.

But these adjustments rely on each prison officer's judgement and experience. Prison officers told us that they ask the PDSI, DCNS or disability support officers for help with some prisoners.

There is no mandatory training or guidelines for prison officers about:

- recognising the signs of cognitive impairment

- how to adapt programs and activities to individual prisoners' needs.

This means that the level and quality of reasonable adjustments varies across the corrections system.

DJCS only has 2 adapted offending behaviour programs

Types of adapted offending behaviour programs

DJCS has only adapted 2 offending behaviour programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury.

These programs are for:

- violent offenders

- sex offenders.

There are no other adapted offending behaviour programs for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury who commit other types of crimes.

As a result, DJCS does not give these prisoners the best chance of rehabilitation. This is because they do not get treatment targeted to their needs.

DJCS's 2017–18 Budget bid to introduce a screening tool also included funding to make and deliver adapted family violence and general offending programs for prisoners with a cognitive impairment. But this was not successful.

DJCS and DFFH do not regularly and comprehensively evaluate their services

Evaluating services

There are many factors that contribute to a person reoffending. There are also various measures that can be used to evaluate prison services.

But it is important that DJCS and DFFH assess if their specialised accommodation and programs are reducing reoffending. Because it will tell them if the services are working as intended and if they should be continued.

Evaluating specialised accommodation

DJCS has not evaluated if its beds for prisoners with intellectual disability or an acquired brain injury are effective.

This means DJCS does not know:

- if these beds reduce reoffending

- how it can improve them.

Evaluating adapted offending behaviour programs

DJCS has not evaluated if its adapted offending behaviour programs are effective.

This means DJCS does not know:

- if these programs reduce reoffending

- if these programs meet prisoners' needs

- how it can improve these programs

- if other programs to target different types of crimes would be useful.

DJCS is currently drafting a plan to evaluate all its offending behaviour programs.

DJCS told us that this might include assessing if the programs are reducing reoffending, among other measures.

But it has not finished this plan and its management have not approved it.

Updating adapted offending behaviour programs

The content for DJCS's adapted program for violent offenders is a draft. And it has not reviewed or updated it since 2012.

It has not reviewed or updated its adapted program for sex offenders since 2016.

This means that DJCS does not know if these programs still reflect better practice and are up to date.

Evaluating support programs

DJCS evaluated the PDSI and DCNS as part of its Budget bids. It assessed:

- the programs' activities and operations

- if the programs achieved their short-term outcomes

- what changes it needs to make to improve them.

DJCS started running the PDSI in July 2021 and the DCNS in July 2020.

It is too early to tell if these programs are achieving their long-term outcomes, including reducing reoffending.

DJCS told us that it does not have the funding to assess their long-term outcomes.

Evaluating DFFH's forensic disability service

DFFH evaluated its forensic residential service in 2017. It looked at the service's activities and clinical operations.

It did not assess the reoffending rates of people who have used it.

DFFH has not evaluated its disability justice coordination service.

In its 2022–23 Budget bid submission DFFH evaluated the reoffending rates of prisoners:

- with intellectual disability

- with cognitive disability

- who have used its service.

This was a one-off evaluation. It is the only time DFFH has looked at reoffending rates in the last 5 years.

DFFH does not regularly assess or report if its service is effective.

This means it does not know:

- if the service is working

- what it needs to improve

- if any previous changes have reduced reoffending rates.

DFFH has received funding in the 2023–24 Budget to further develop:

- a linked data strategy across complex needs and forensic disability services

- funding for research and program evaluation to better integrate data across systems

- the evidence base for interventions that will best support clients.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A: Submissions and comments.

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Download a PDF copy of Appendix C: Audit scope and method.