Managing Surplus Government Land

Overview

It is important that the government manage its landholdings effectively and efficiently to ensure it is making best use of available resources. The need for governments to own land changes in response to population growth and shifting demand for public services. As needs change, government land may become surplus to requirements. The sale of surplus public land generates significant revenue for government and attracts strong community interest.

This report examines whether government agencies are achieving the best value possible from surplus land.

As the government introduced new policies for managing government land in 2015 and 2016, the audit focuses on surplus land sales conducted under the new policy framework. We examined whether:

- the systems and targets used by agencies support the best use of surplus land

- agencies accurately identify surplus land and release it for sale in a timely way

- agencies can demonstrate value from the sale of surplus land.

The audited agencies were the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF), the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Department of Health and Human Services including the Director of Housing, the Department of Education and Training, and Victorian Rail Track.

We made two recommendations for DTF, five recommendations for DELWP, two recommendations for land-selling agencies, and a further four recommendations for DTF and DELWP.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2018

PP No 380, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Managing Surplus Government Land.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

8 March 2018

Acronyms and abbreviations

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DJR | Department of Justice and Regulation |

| DoH | Director of Housing |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| FROR | First right of refusal |

| FTGLS | Fast Track Government Land Service |

| LUV | Land Use Victoria |

| OBE | Outer budget entity |

| OSGV | Office of Surveyor-General Victoria |

| SCLA | Strategic Crown Land Assessment |

| SLUA | Strategic Land Use Assessment |

| TAFE | Technical and further education |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VGLM | Victorian Government Land Monitor |

| VGV | Valuer-General Victoria |

| VicTrack | Victorian Rail Track |

Audit overview

The need for governments to own land changes in response to population growth and shifting demand for public services. As needs change, government land may become surplus to requirements. The sale of public land generates significant revenue for government and attracts strong community interest. Over the past 10 financial years, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has sold 695 properties, generating over $928.7 million of sales revenue for the state.

While the Victorian Government owns 8.8 million hectares of land—around 40 per cent of the state—almost 68 per cent of this is national parks and state forests.

The government needs to manage its landholdings effectively and efficiently to ensure it is making best use of available resources. This is particularly important in and around Melbourne, which is facing unprecedented population growth and land pressures.

Past reviews have identified a lack of accountability and transparency in developments involving government land. These reviews highlighted the need for a long-term, strategic approach to managing surplus land.

In 2015 and 2016, the government introduced a new policy framework for managing government land, and made a number of changes including:

- establishing Land Use Victoria (LUV) to bring together key land administration functions and provide whole-of-government advice on determining the best use of government land

- improving the first right of refusal (FROR) process, which provides an opportunity for government agencies and councils to purchase surplus government land prior to public sale

- developing the Fast Track Government Land Service (FTGLS) to expedite the rezoning of government land.

This report examines whether government agencies are achieving the best value possible from surplus land.

Our audit focused on DTF, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) including the Director of Housing (DoH), the Department of Education and Training (DET), and Victorian Rail Track (VicTrack).

DTF manages the sale of the majority of surplus government land. VicTrack and DoH, due to their statutory powers, own and sell land independently, reinvesting the sale proceeds in their own portfolios.

Conclusion

Existing systems and processes do not support a strategic whole-of-government approach to making the best use of surplus government land. The lack of complete and accurate information on agency landholdings, and differing approaches to assessing land use, limit government's ability to make informed, strategic choices and achieve best value from surplus land.

Established in late 2016, LUV plans to address the issue of whole-of-government strategic land management to better inform decision-making and maximise value.

LUV is improving access to information about government land use, by creating Govmap—an online tool that brings together a range of datasets on government land which are currently held in different systems by different agencies.

The ongoing use of land sales targets does not support agencies in achieving best value from surplus land. In particular, the stretch targets assigned to agencies are not evidence based and drive agencies to prioritise the sale of surplus land rather than considering whether another option would achieve best value, such as a commercial lease or retaining a site for community use. The target setting has had some positive outcomes, however, as it has encouraged agencies to assess their landholdings and identify surplus sites.

Findings

Best use of surplus government land

Administrative policies and processes do not support agencies to make the best use of their surplus government land. Current policies emphasise the financial value of land and do not provide guidance to agencies on how to achieve best value.

Following significant government land sales since the 1980s, there are now relatively few surplus sites. The majority of these have impediments to sale such as a rural location, contamination, ongoing native title negotiations or a long‑term lease. However, opportunities remain for government to unlock value from under-utilised sites.

LUV has developed the Victorian Government Land Use Policy and Guidelines, which includes a new definition of 'public value' designed to improve whole‑of‑government decision-making about government land use. Currently, agencies do not share a common understanding of value, which led to inconsistencies in how agencies assessed their landholdings and considered the future use of surplus sites.

The new definition considers intergenerational, social and environmental values, as well as economic benefits. It also focuses on best value from a whole‑of-government perspective, whereas current policies only require agencies to consider their own portfolio-specific needs. Government approved the final version of LUV's policy in December 2017.

LUV has also developed a new process to provide advice on achieving best value from government land, which includes Strategic Land Use Assessments (SLUA). As part of this, LUV provides general advice and undertakes basic SLUAs in addition to comprehensive SLUAs. However, LUV only has limited capacity to perform SLUAs, so there is a risk that the full benefits of the SLUA process will not be realised.

First right of refusal process

The FROR process does not maximise the opportunity to retain surplus land within government. Few agencies or local councils purchase sites through the FROR process. Agencies find it difficult to meet the required 60-day time frame for expressions of interest, and many are unaware that they can request an extension. The increasing market value of land also impedes agencies' ability to buy surplus government land, particularly where the agency intends to purchase and retain the land for community use rather than financial benefit.

Sale of Crown land

Conducted by DELWP's regional offices, Strategic Crown Land Assessments (SCLA) determine whether surplus Crown land sites have significant public value and recommend protection mechanisms. Delays in the timely completion of SCLAs lead to potential inefficiencies and wastage of resources, such as increased holding costs for saleable properties. Since 2016, the average time taken to complete SCLAs has increased beyond the 90-day time frame. While the overall average time delay has been minor, DET has faced significant delays—between May and July 2017, it submitted 26 sites for SCLAs, but by December 2017, DELWP had only completed one of them. DELWP has advised that there are not enough resources allocated at the regional level to complete SCLAs.

Native title negotiations can also delay the sale of Crown land. DTF and the Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR) are working with traditional owner groups to expedite the process.

Reporting on land use

It is difficult for government and agencies to make sound decisions about future land use because the existing data on landholdings is inaccurate and incomplete.

Each year, landholding departments report to DTF on their landholdings, including assessing how each site is used and identifying any surplus land.

While all agencies have gaps in their information about land use, DELWP's ability to report on its landholdings is particularly limited due to the scale of its landholdings and historical limitations in land administration. DELWP is in the process of addressing these data gaps and improving its land management systems.

Agencies are not using the full range of categories available when assessing the utilisation status of their sites. This is due to agencies' lack of focus on the assessment process, and the absence of clear guidance on how agencies should categorise their sites. In addition, some categories are only of limited relevance to describe agencies' landholdings. For example, DET's properties are either 'fully occupied' by a school or 'vacant with no agency utilisation planned' when surplus to requirements. As a result, government does not know how much land is currently under- or partly utilised.

Rezoning

Until recently, rezoning was the largest impediment to the timely sale of surplus land. Prior to the establishment of FTGLS in 2015, a significant number of DET sites remained surplus for years because local councils did not process the planning amendments required to facilitate a sale. FTGLS has reduced the average time taken to rezone land after an agency submits an application, from over 18 months previously to six months. As a result, the time frame for land sales requiring rezoning has reduced significantly, leading to improved efficiencies and savings.

Demonstrating value from the sale of surplus government land

Government has achieved significant financial value from the sale of surplus government land. Over the past two financial years, DTF's surplus government land sales have generated $263.7 million of revenue, with total selling costs negligible in comparison. However, the ongoing use of land sales targets does not support agencies to achieve best value from surplus land. In particular, the stretch targets assigned to agencies are not based on evidence and force agencies to prioritise the sale of surplus land rather than considering whether another option would achieve best value.

Costs and benefits

DTF and landholding agencies do not assess the costs of continuing to own and maintain under-utilised or surplus land when considering a parcel of land for sale. This is particularly relevant for low-value sites, such as those worth less than $15 000, and those that bear significant sale barriers such as contamination where the sale costs would exceed the sale revenue. A more holistic assessment of the costs and benefits may result in land sales that, while initially not revenue generating, result in longer-term cost savings.

Land sales targets

Since the Victorian Government introduced land sales targets in August 2015, the overall value of sites that agencies refer to DTF for sale has exceeded the annual target. However, not all departments have met their targets each year. Land sales targets do not support agencies to achieve best value from surplus land.

The government's sales targets aim to provide an incentive for agencies to refer land for sale. However, most agencies do not view the opportunity to access 10 per cent of the sale proceeds as an incentive. To date, agencies have only accessed $2.6 million of their net sales proceeds. This is less than 1 per cent of the total proceeds from DTF's land sales since the introduction of targets.

In 2017–18, the government set stretch targets in addition to the base targets that agencies had agreed to. Agencies had agreed to an overall target of $93 million, and government added a further $87 million as a stretch target. The stretch targets were not evidence based. DTF advised that the stretch targets were set to make up the shortfall in land identified as surplus by departments.

In 2017–18, for the first time, the government set outer budget entities (OBE) a collective land sales target of $300 million over four years. Seventy-five government entities are classified as OBEs, including water authorities, technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and VicTrack.

In January 2017, DTF commissioned consultants to perform a desktop review of assets held by OBEs to help in allocating the $300 million collective target to individual entities. The government used the review's preliminary report to establish the $300 million target. DTF received the final report in June 2017, which indicated that some OBEs had surplus sites that could contribute to meeting the sales target.

VicTrack has indicated that a large number of its identified sites are difficult to sell and that the overall target is unrealistic. Further, it expressed concern that receiving a target could pose a risk to its financial sustainability, as VicTrack funds its operations from outside the state's general Budget.

Timeliness and efficiency of sales process

The three audited agencies that manage land sales—DTF, DoH and VicTrack—have efficient processes for selling land, and they run processes in parallel to minimise delays. The length of time it takes agencies to sell a site varies considerably based on the attributes of each individual site. For example, there is less demand for small regional sites—typically owned by DELWP or DJR—than there is for the residential sites held by DoH.

Leasing

There is limited evidence that landholding agencies are exploring all options to achieve best value from surplus land such as leasing, which represents a missed opportunity. While agencies sometimes lease surplus sites, they do not actively identify leasing opportunities. Land sales targets encourage agencies to refer sites for sale rather than leasing them—for either commercial rent or community use. On vacant sites where agencies have identified a future use, there is scope for short-term leasing or shared-use options. As an example of better practice, VicTrack proactively considers leasing opportunities prior to sale and, as a result, manages over 1 500 leases on its sites.

Contaminated sites

Government agencies are not maximising value from contaminated surplus sites. Contamination poses environmental and health risks, and increases the cost of preparing surplus land for sale.

DTF and VicTrack have actively assessed contamination risks and, if warranted by a cost–benefit analysis, remediated sites prior to sale.

DELWP has not secured funding to implement the same approach, despite also owning a number of surplus sites that, if remediated, could generate revenue. Currently DELWP does not have any information on how many of its sites are contaminated or the resources needed to remediate them.

Recommendations

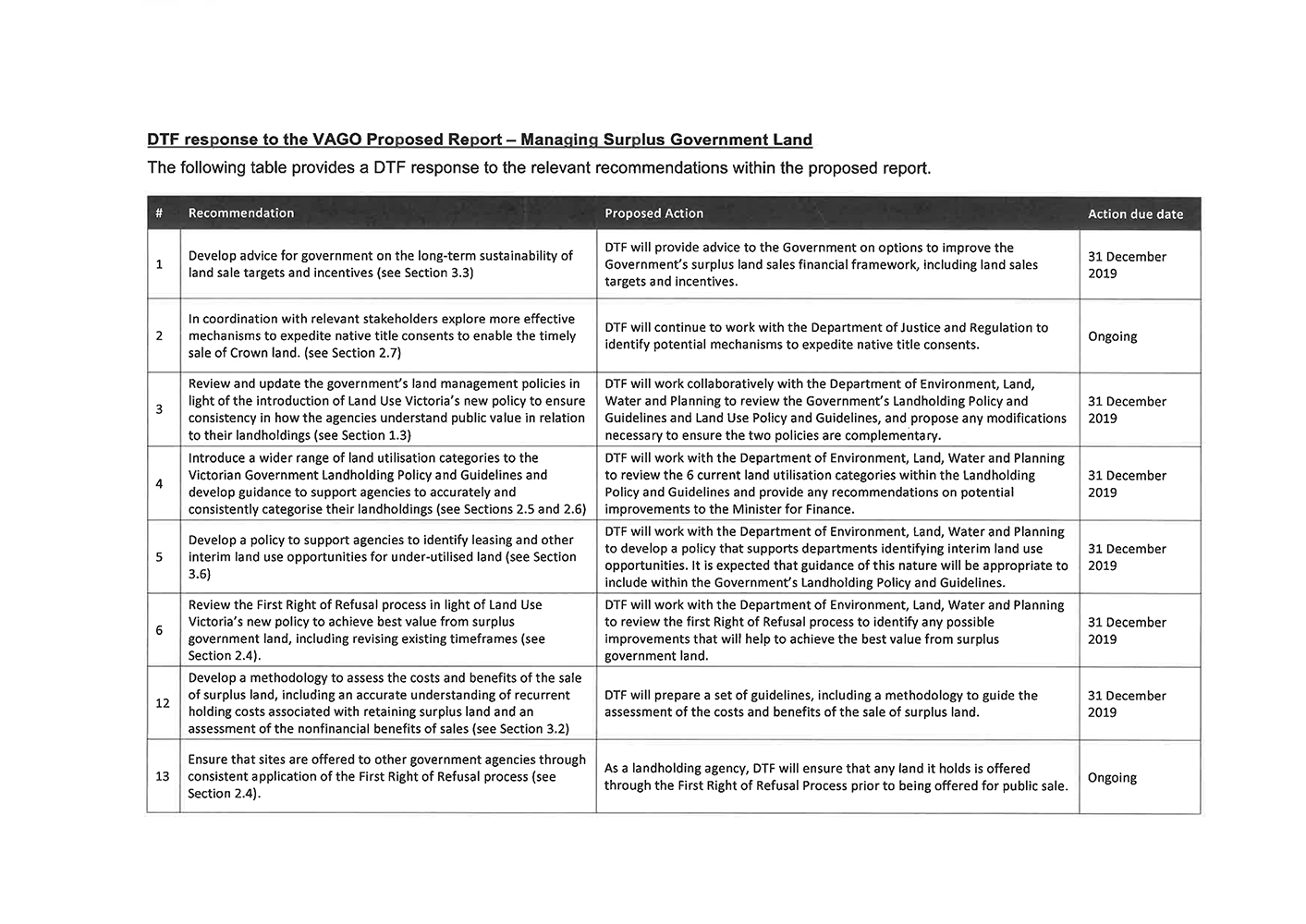

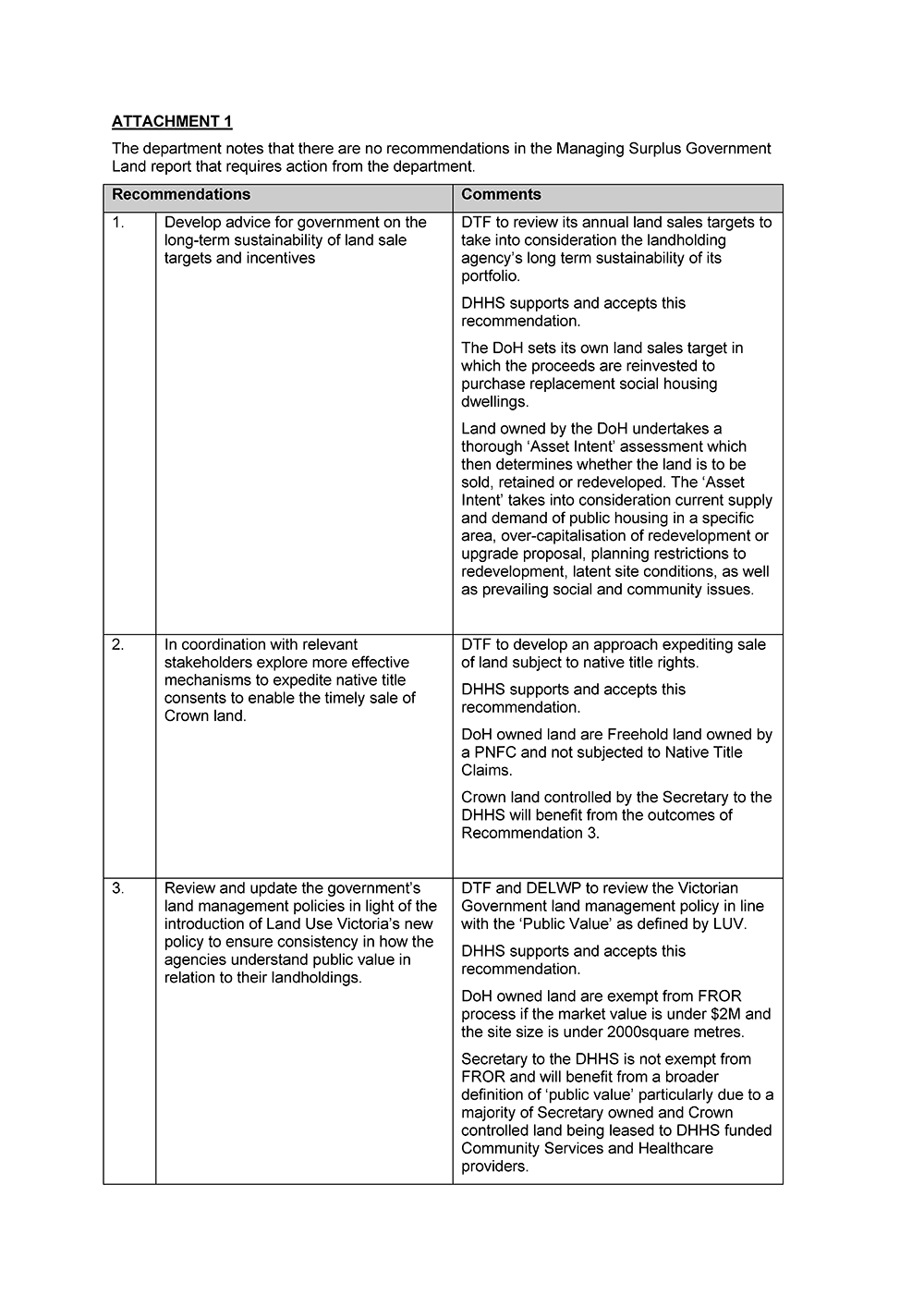

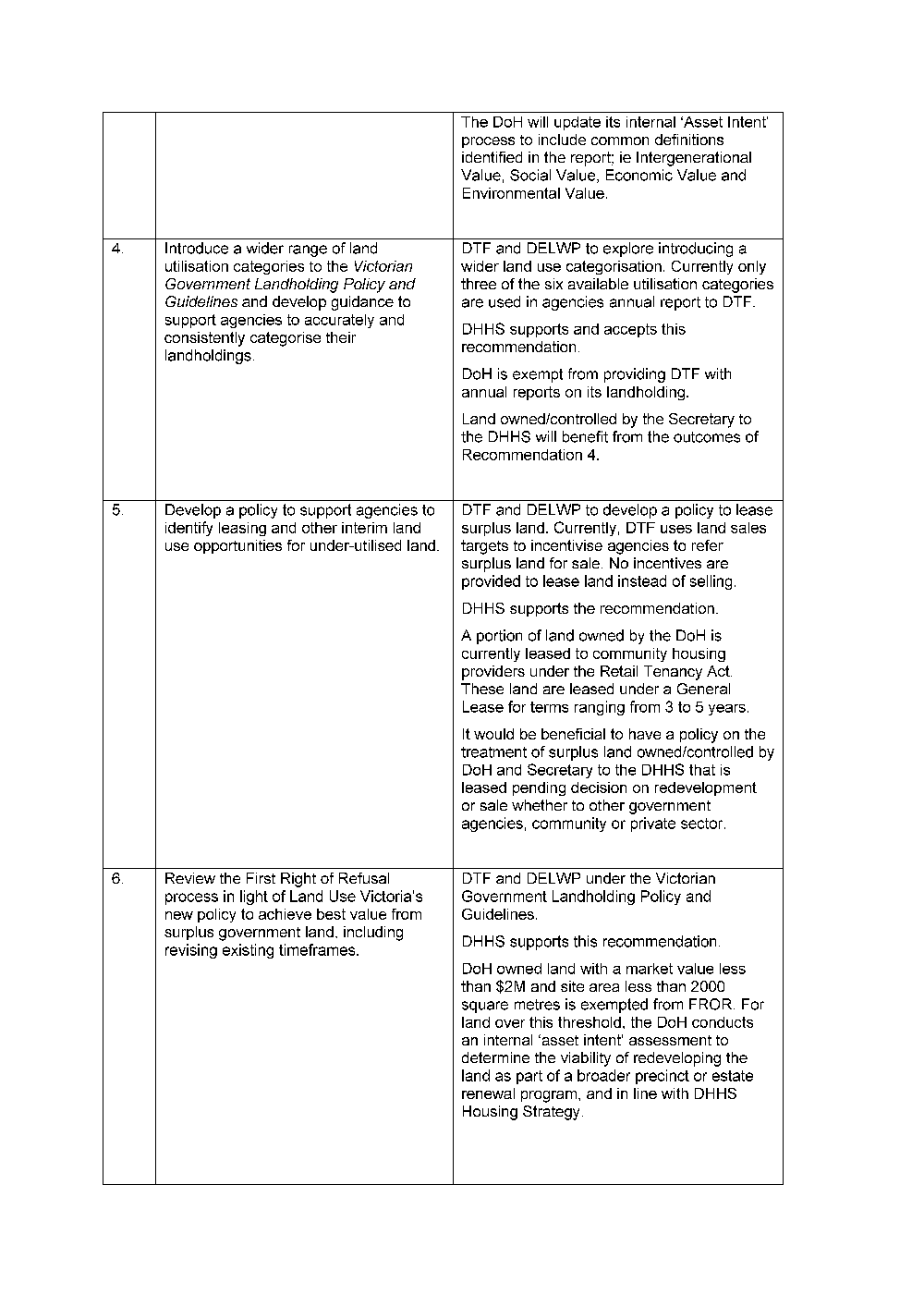

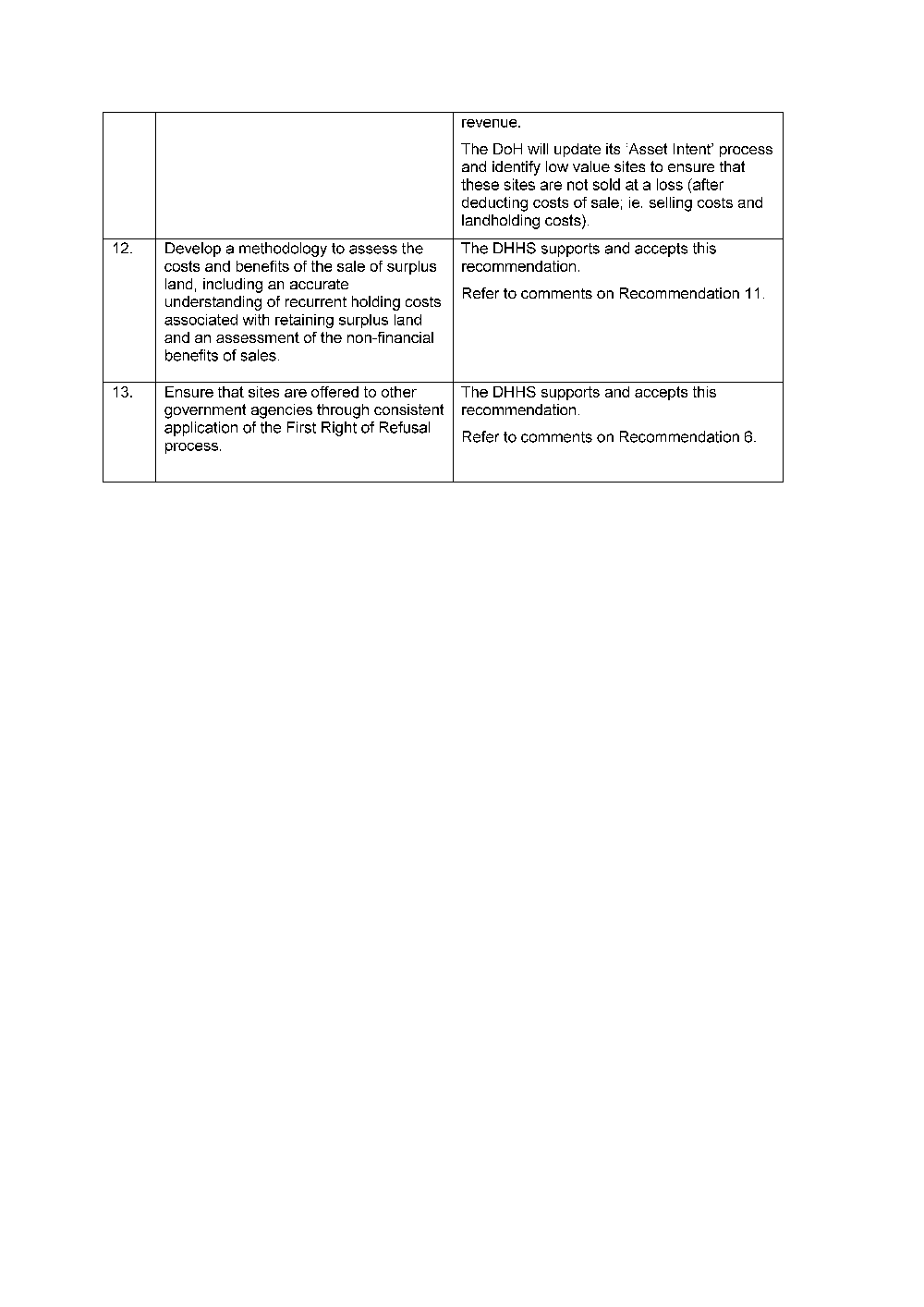

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance:

- develop advice for government on the long-term sustainability of land sale targets and incentives (see Section 3.3)

- in coordination with relevant stakeholders, explore more effective mechanisms to expedite native title consents to enable the timely sale of Crown land (see Section 2.7).

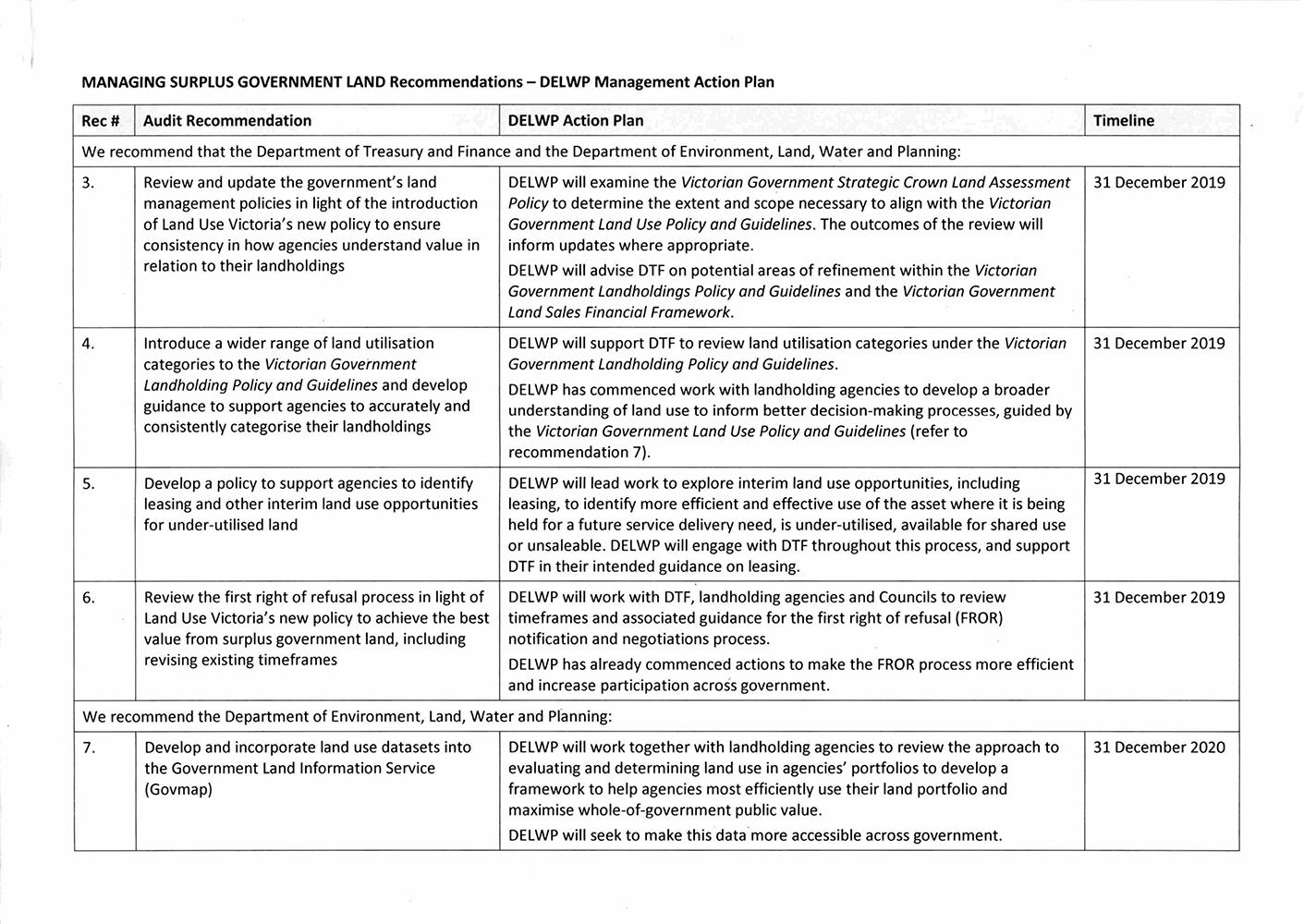

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance, and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- review and update the government's land management policies in light of the introduction of Land Use Victoria's new policy to ensure consistency in how the agencies understand public value in relation to their landholdings (see Sections 1.4 and 2.2)

- introduce a wider range of land utilisation categories to the Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines and develop guidance to support agencies to accurately and consistently categorise their landholdings (see Sections 2.5 and 2.6)

- develop a policy to support agencies to identify leasing and other interim land use opportunities for under-utilised land (see Section 3.6)

- review the first right of refusal process in light of Land Use Victoria's new policy to achieve best value from surplus government land, including revising existing time frames (see Section 2.4).

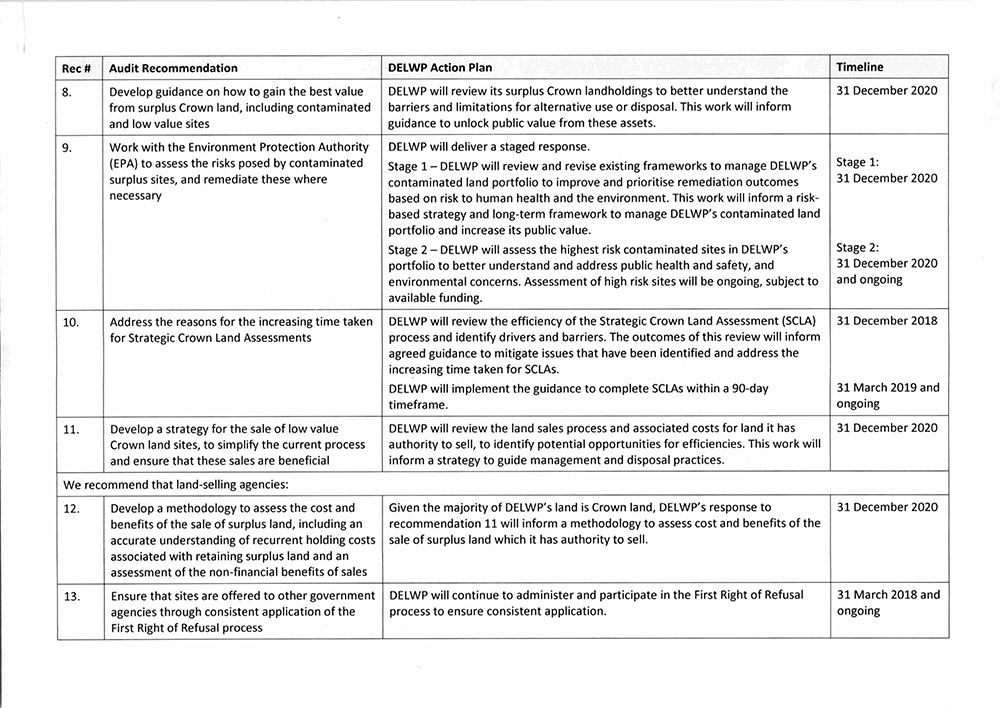

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- develop and incorporate land use datasets into the Government Land Information Service (see Section 2.6)

- develop guidance on how to gain the best value from surplus Crown land, including contaminated and low-value sites (see Sections 3.2 and 3.7)

- work with the Environment Protection Authority to assess the risks posed by contaminated surplus sites, and remediate these where necessary (see Section 3.7)

- address the reasons for the increasing time taken for Strategic Crown Land Assessments (see Section 2.7)

- develop a strategy for the sale of low-value Crown land sites, to simplify the current process and ensure that these sales are beneficial (see Section 3.2).

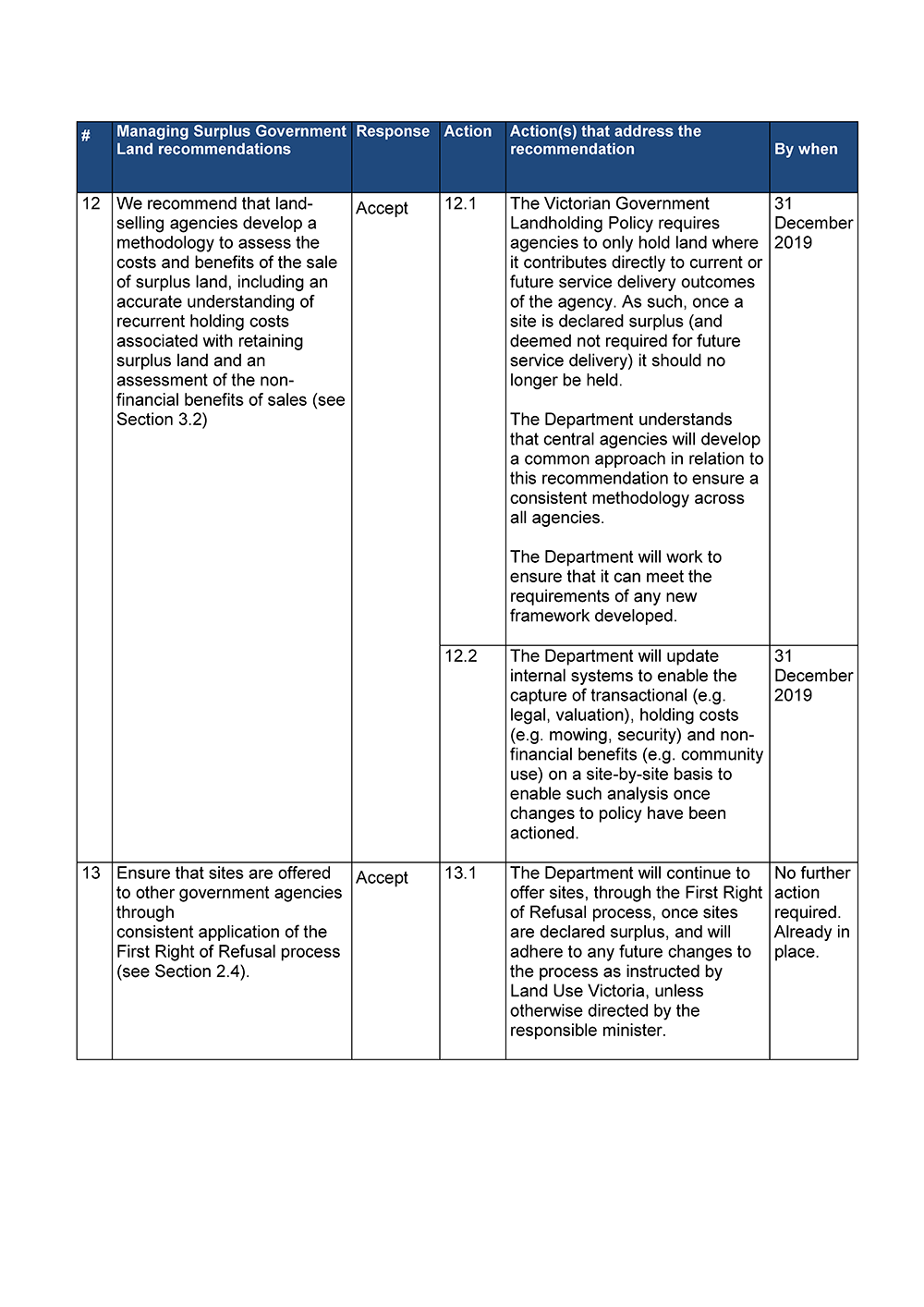

We recommend that land-selling agencies:

- develop a methodology to assess the costs and benefits of the sale of surplus land, including an accurate understanding of recurrent holding costs associated with retaining surplus land and an assessment of the non‑financial benefits of sales (see Section 3.2)

- ensure that sites are offered to other government agencies through consistent application of the first right of refusal process (see Section 2.4).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DTF, DELWP, DET, DHHS and VicTrack, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of this report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

DTF, DELWP, DET and DHHS have responded to the recommendations with an action plan outlining their proposed approach to addressing the issues raised. DELWP also stated that work has already commenced on several of the recommendations.

VicTrack acknowledged that, while there are no specific recommendations directed towards it, there are some improvements for it to address.

1 Audit context

Governments own land for a variety of public purposes, including for housing, health, education, police services, and for community activities, sport and recreation. Governments also own land to protect its environmental or heritage value in the form of national and state parks or reserves.

The need for government to own land changes over time, in response to demand for public services, population change or new policy priorities. As a result, there will always be some land that becomes surplus to government needs.

Each year, Victorian Government agencies are required to review their landholdings to determine whether they continue to provide the maximum benefit to the state. Land that is identified as surplus is first offered to other government agencies, and then for private sale. The proceeds from the sale of government land contribute to funding public services and infrastructure.

1.1 Victorian Government landholdings

Categories of land

Land owned by the Victorian Government falls into two categories:

- Crown land—land held by the Crown in right of the State of Victoria. The state government may give another person the ability to manage or control that land, for example, in the case of pastoral leases, community-managed reserves and public roads.

- Freehold land—land that has been alienated from the Crown through the issuing of a Crown grant freehold title. This means that the landholder has unrestricted ownership and the right to deal with the land, subject to complying with applicable laws. A number of Victorian Government agencies own freehold land purchased from private owners.

The Victorian Government owns approximately 8.8 million hectares of land— around 40 per cent of the state—with a value of around $114 billion. This includes both freehold and Crown land, and 242 000 land titles managed by 272 different public sector entities. Crown land is either:

- reserved for a public purpose—such as national parks, schools, policing or transport infrastructure

- unreserved—allotments that have not been set aside for a public purpose.

As shown in Figure 1A, almost 68 per cent of Victoria's state-owned land is national parks and state forests.

Figure 1A

Victorian state-owned land, by type and area (millions of hectares)

Source: VAGO based on information from LUV.

Around 87 per cent, or 7.7 million hectares, of state-owned land is reserved Crown land, including national parks and state forests.

The majority of freehold land is located in metropolitan Melbourne, while the bulk of Crown land is in rural and regional areas.

1.2 Agency roles and responsibilities

The Victorian Government's land management polices—see Section 1.4—assign all departments and agencies responsibilities for their surplus land including:

- maintaining a complete, accurate and current dataset of all land they control

- assessing their landholdings to identify surplus land

- preparing surplus land for sale in accordance with relevant government polices.

Landholding ministers are responsible for declaring land as surplus and approving its sale.

First right of refusal process

Once an agency has identified land as surplus, it is offered to other government agencies—including councils and Commonwealth Government entities—through the FROR process. LUV, within DELWP, administers the FROR process, which includes the following steps:

- An agency declares a site as surplus and must offer the site to other agencies through the FROR process.

- LUV emails a list of sites that are part of the FROR process to all agencies approximately fortnightly.

- Agencies have 60 days to submit an expression of interest in acquiring the surplus land for a public or community purpose.

- If an agency expresses an interest within 60 days, the parties must attempt to agree on the terms of sale within 30 days, and the transfer of land can proceed at a price equal to the current market value of the land, determined by Valuer-General Victoria (VGV). The policy allows for the parties involved in the transaction to extend the negotiation period with mutual agreement.

- Local councils have the opportunity to purchase land for community use and pay a lower amount based on a restricted use of land, with the approval of the landholding minister.

- If no agency expresses an interest in a site, or if the terms of sale are not agreed, the landholding agency can dispose of the surplus land through a public process, in accordance with the Victorian Government Land Transactions Policy.

Department of Treasury and Finance

The Land and Property Group within DTF provides advice to government agencies on the future use or disposal of surplus government land. DTF administers key policies about government landholding and manages the sale of surplus land for all government departments and agencies apart from:

- VicTrack

- VicRoads

- DoH, part of DHHS

- DELWP, for private treaty sales valued at less than $100 000.

The government sets targets for each department for the sale of surplus land. DTF administers this process and reports on the performance of the departments. For the 2017–18 State Budget, DTF has a target of achieving $200 million from the sale of surplus land.

DTF historical property sales

Over the past 10 financial years, DTF's Land and Property Group sold 695 properties, generating over $928.7 million of sales revenue for the state. In 2016–17, DTF sold 65 surplus properties, generating $130.4 million. From 1 July to 30 September 2017, the sale of surplus land generated $16.6 million.

Property sales have fluctuated significantly since 1986, as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Revenue from DTF's sale of surplus property since 1986

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DTF.

The significant increase in land sales between 2012 and 2014 was due to the piloting of a new rezoning process that saw several high-value DET sites sold for residential development, as well as the sale of 23.61 hectares of vacant residential land in Point Cook which sold for $103.8 million.

Following the surge in sales of government land in the late 1980s and 1990s and the more recent high-value sales activity, there is less surplus land left. The sites that remain usually have impediments to sale including rural locations, native title claims, long-term leases and community sensitivities.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

Land Management Policy Division

DELWP's Land Management Policy Division is responsible for policy and oversight of Victoria's Crown land. DELWP's regional offices are primarily responsible for the day-to-day management of Crown land and manage the sale of DELWP's low-value surplus sites. Before agencies sell potentially surplus Crown land, DELWP regional offices complete an SCLA to identify whether:

- a site has any public land values that require protection

- native title or traditional owner rights exist over the site.

Fast Track Government Land Service

Traditionally, government-owned land is zoned for public use, meaning that, prior to sale, surplus land needs rezoning to allow other uses. DELWP established FTGLS in 2015 to expedite the rezoning process and ensure that the appropriate planning provisions are in place prior to the sale of government land. Previously, agencies needed to apply to the relevant local council for a planning scheme amendment.

Land Use Victoria

Established in October 2016 within DEWLP, LUV is the Victorian Government's agency for land administration, property information, and strategic advice on the best use of government land.

LUV includes the following groups and statutory offices:

- Government land information, policy and advice supports government to maximise public value from land it owns through information and advisory services and land use policy.

- Victorian Government Land Monitor (VGLM)—oversees all land sales with a value of $750 000 or more (excluding GST) to provide government with assurance of accountability, impartiality, transparency and integrity in land transactions.

- VGV—land transactions with or between government agencies use valuations undertaken by VGV, the state's independent authority on property valuations.

- Office of Surveyor-General Victoria (OSGV)—determines and approves land boundaries, corrects government land titles, and certifies the status of Crown grants.

- Registrar of Titles—responsible for registering titles and recording Crown grants.

In December 2017, government approved LUV's Victorian Government Land Use Policy and Guidelines, which introduces a common definition of 'public value' and outlines a strategic, whole-of-government approach to decision-making about the use of government land.

VicTrack

VicTrack owns all rail and tram lines, and other rail infrastructure in Victoria. VicTrack leases the majority of its assets to Public Transport Victoria, which then leases them to the public transport operators. VicTrack manages its own landholdings and reinvests the revenue from any land sales, leases and licenses into maintaining VicTrack assets. The exception to this is that, for the sale of Crown land vested in VicTrack, the net proceeds of sale are remitted to consolidated revenue, after taking into account the costs of sale and VicTrack's assessed interest in the land, as determined by VGV.

Director of Housing

Although based within DHHS, DoH is a separate legal entity under the Housing Act 1983, with responsibility for managing a public housing portfolio of 64 000 properties valued at approximately $23 billion. DoH conducts its own land sales and reinvests the proceeds in maintaining its public housing assets. DoH is exempt from land sale targets, and its residential properties are exempt from the FROR process if their market value is under $2 million and the site size is under 2 000 square metres.

1.3 Land sale process

Figure 1C shows the process for selling surplus government land. The process differs depending on whether a site is freehold or Crown land, and whether a site requires rezoning.

Figure 1C

Overall surplus government land sale process

Source: VAGO.

1.4 Legislative and policy framework

A range of legislation impacts the sale and management of surplus land, including:

- Sale of Land Act 1962—regulates the sale of freehold land

- Transfer of Land Act 1958—establishes the system of land titles

- Land Act 1958—covers the management and sale of Crown land

- Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978—enables Crown land to be reserved for specific public purposes

- Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 and Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) provides for the recognition of traditional owner rights in relation to Crownland

- Planning and Environment Act 1987—provides the legal framework for Victoria's planning system, including provisions for the rezoning of land

- Valuation of Land Act 1960—regulates the valuation of government land and establishes VGV.

In addition, there is legislation that provides specific agencies with functions relating to the purchase and sale of land, such as the Housing Act 1983 for DoH and the Transport Integration Act 2010 for VicTrack. Other legislation relating to the land sale process is listed in Appendix B.

DTF and DELWP administer the four key policies that underpin the Victorian Government's land management framework, summarised in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Victorian Government land management policies

|

Policy/guideline |

Department |

Role |

|---|---|---|

|

Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines, 2015 |

DTF |

Outlines the circumstances in which government agencies may purchase and retain land. Applies to the entire Victorian public sector. |

|

Victorian Government Land Sales Financial Framework, 2015 |

DTF |

Sets the financial framework for the sale of surplus government land. Includes surplus land sales targets intended to provide an incentive for agencies to identify and release land for sale in a timely way. |

|

Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines, 2016 |

DELWP |

Establishes the SCLA process to identify and evaluate public land values for surplus Crown land. Lists assessment criteria such as the heritage, cultural and environmental value of the land and the status of traditional owner and native title rights. |

|

Victorian Government Land Transactions Policy and Guidelines, 2016 |

DELWP |

Provides for the probity and transparency of the process used by agencies when selling, acquiring or leasing land, and establishes VGLM. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DTF and DELWP.

1.5 Past inquiries and reviews

Select Committee of the Legislative Council on Public Land Development

In 2008, the Victorian Parliament's Select Committee of the Legislative Council on Public Land Development identified a range of issues with the system for assessing and disposing of surplus land. Since then, the government has taken steps to improve land management practices across the public sector.

The committee's findings on the development of public land included that:

- public land and open space are valued by communities, who are keenly and actively interested in its preservation

- the disposal of public land and open space is biased toward short-term commercial gain to the detriment of existing and potential community uses and environmental, cultural and heritage values

- there was a lack of transparency and accountability in public land dealings, with government assessments of public land values having little or no public input

- the state government needed a long-term, strategic and coordinated approach to the management and disposal of public land.

Regional Economic Development and Services Review

In 2015, the Regional Economic Development and Services Review—an independent review commissioned by the government—highlighted that without a clear statewide policy framework, the economic potential of surplus land assets remained untapped.

The review recommended that the Victorian Government build on existing land use planning processes and act on opportunities where further development or alternative uses would help realise their economic potential.

The government responded with its framework of policies and guidelines—see Figure 1D—intended to address the recommendations and community concerns, and the establishment of LUV in 2016.

1.6 Why this audit is important

The community places a high value on public land, particularly open space. The sale, lease or development of government-owned land can create a strong reaction from local communities and interest groups. To meet the challenges of Victoria's growing population and increasing demand for government services, government should make best use of its land. This includes efficiently and effectively identifying and disposing of surplus government land.

While we have recently conducted audits broadly related to the management of government land—Managing Contaminated Sites (2011) and Oversight and Accountability of Committees of Management (2014)—the last time we directly examined the management of surplus land was in 1987, with our audit Land Utilisation.

Given the steps taken to enhance land management practices in recent years, it is timely to evaluate whether government's implementation of the policy framework is achieving best value from surplus land.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

Our objective was to determine whether government agencies are achieving the best value possible from surplus land. As the government introduced new policies in 2015 and 2016, the audit focuses on surplus land sales conducted under the new policy framework. We examined whether:

- the systems and targets used by agencies support the best use of surplus land

- agencies accurately identify surplus land and release it for sale in a timely way

- agencies can demonstrate value from the sale of surplus land.

The audited agencies were DELWP, DTF, DHHS including DoH, DET and VicTrack.

We conducted our audit in accordance with Section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $470 000.

1.8 Report structure

The rest of the report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines processes to support the best use of surplus government land

- Part 3 discusses whether agencies are demonstrating value from the sale of surplus government land.

2 Best use of surplus government land

For government to plan strategically and make good decisions about how to make the best use of surplus government land, it needs accurate information. Each year, departments report to DTF on their landholdings. As part of this process, agencies are required to:

- assess the utilisation status of their land assets

- identify any surplus sites

- justify the retention of each site.

This process does not apply to DoH and VicTrack, as they own and manage their own assets.

This part of the report examines the systems and processes government agencies use to determine best use of surplus land.

2.1 Conclusion

Existing government systems and processes do not support a strategic whole‑of‑government approach to making the best use of surplus government land. Lack of a strategic approach increases the risk of inefficient use of government land, such as selling surplus government land that might be needed in the future. A strategic approach requires agencies to consider intergenerational, social, economic and environmental factors when determining the best use of surplus government land. LUV aims to provide a strategic perspective, but its capacity to perform this role is limited due to resourcing constraints.

LUV's new advice function—which includes SLUAs that identify best use opportunities for surplus sites—should improve the effectiveness of the FROR process and encourage the retention of surplus land within government where beneficial.

2.2 Best value

Gaining the best value from government land includes not only financial return, but also the extent to which agencies have assessed and considered the potential future use of government land. Best value can vary depending on the unique attributes of each site. For example, best value for one site may be a low-value sale to an adjoining landowner, while for another, it might be sale to traditional owners or leasing for a community purpose.

Current Victorian Government policies relating to land management define public or 'best' value in a number of ways.

The Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines states that the disposal of surplus land and FROR process aims to 'promote the highest and best use of land by providing the opportunity for the private and community sectors and other government agencies to further unlock the value inherent in the State's land estate'. The policy requires agencies to assess their landholdings against:

- current and future service delivery requirements

- its environmental, heritage and cultural value, including native title.

DELWP's Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines defines the public value of Crown land in terms of the land's inherent heritage, cultural and environmental value, and its value to traditional owners.

LUV's new Victorian Government Land Use Policy and Guidelines (December 2017) introduces a common definition of 'public value' that includes:

- intergenerational value—by considering how land use decisions made today benefit current and future generations, including traditional owners who use the land to pass down their culture to younger generations

- social value—equity of access to health, housing, education and recreational space, and improved local amenity and social inclusion

- economic value—access to employment, and benefits for business and industry

- environmental value—resource use and sustainability, reduction of contamination, emissions and waste, as well as impacts on ecosystems, biodiversity and climate change.

This is a significantly wider definition than is currently used in the government's other land management policies.

2.3 Strategic Land Use Assessments

LUV aims to support agencies to identify and create public value from surplus or under-utilised land. As part of LUV's advisory function, one of its roles is to perform SLUAs, to recommend options for the future use of government land from a whole-of-government perspective, as opposed to an agency-specific view. Typically, agencies consider their portfolio needs and assess their landholdings in isolation from each other.

Drawing on relevant information and expertise—and with reference to whole‑of-government priorities—SLUAs identify high-level options to inform the decision-making of ministers and Cabinet. The SLUA process aims to ensure future land use options align with needs and provide public value across portfolios.

Government can refer strategically significant sites to LUV for an SLUA. As the administrator of the FROR process, LUV can also proactively identify sites and consider whether a site is suitable for an SLUA. Under the Victorian Government Land Use Policy and Guidelines, LUV has standing authorisation to undertake a basic SLUA on sites in metropolitan Melbourne with a value over $5 million or a value over $3 million in other areas of the state. LUV also considers sites larger than 5 000 square metres within areas of state or regional significance, as defined by the government's metropolitan planning strategy, Plan Melbourne.

Once LUV identifies a site, it decides whether to:

- complete a basic SLUA

- complete a full SLUA for complex sites, which involves more research and more detailed recommendations

- provide advice and assistance to the landholding agency on alternate uses.

While the priorities of individual agencies drive the FROR process, SLUAs aim to help agencies to consider the best possible use of a site, which could include shared use or a development opportunity, rather than a straightforward sale. SLUAs also consider intergenerational equity by assessing future use scenarios and service needs. SLUAs do not provide a full cost–benefit analysis of development options, but do identify the potential risks and benefits of a particular approach to developing a surplus or under-utilised site.

Full SLUAs are authorised by the Premier, the Special Minister of State or Cabinet and are reported back to Cabinet via the Minister for Planning. Landholding ministers, or the secretary or chief executive of a landholding agency can also request advice on a site, project or issue within their portfolio.

In the 2017–18 State Budget, LUV sought funding to expand its capacity to undertake SLUAs and provide advice to agencies. LUV received only partial funding and, as a result, still has limited capacity to deliver SLUAs.

To date, LUV has completed basic SLUAs on the former Victoria University Student Village site in Maidstone, and a surplus parcel of VicTrack land in Spotswood, as well as a full SLUA for DHHS on site options for a new forensic mental health facility. LUV is preparing a further three SLUAs on other government sites.

2.4 First right of refusal process

The Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines outlines the FROR process which requires agencies to offer surplus land to other state, local and Commonwealth government agencies before the public. This supports the retention of land within government.

Between August 2014 and March 2017, agencies listed 829 sites through the FROR process. Of these:

- 3.6 per cent were purchased by government agencies or local councils

- 12.1 per cent were purchased by members of the public after agencies had shown no interest

- 81.7 per cent are still awaiting public sale, with no agencies showing interest in them

- a small number were reassessed by agencies as no longer surplus.

The agencies examined in this audit have rarely purchased a site through the FROR process. DoH and DET regularly acquire land to deliver their services, however suitable sites are rarely available through the FROR process when required.

The case study in Figure 2A provides an example of a sale between agencies, using the FROR process. The case study illustrates the lengthy nature of the process—eight years—and the delays that can result from rezoning and a change of government.

Figure 2A

Case study: Sale of the former Altona Gate Primary School site using the FROR process

|

In 2009, Altona Gate Primary School merged with Bayside P–12 College, and the Minister for Education declared the Altona Gate site surplus to the requirements of DET's predecessor, the former Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Between 2009 and 2013, the department conducted due diligence to prepare the site for sale, however rezoning caused a significant delay. In 2013, the department piloted a new approach to rezoning former school sites and included the former Altona West Primary School site in a 'tranche' of sites to be rezoned in Hobsons Bay City Council, Brimbank City Council and the City of Darebin. The department undertook an updated disposal analysis and found there was a low risk associated with selling the site as neighbouring schools had sufficient enrolment capacity to meet future need. The site was first offered for sale through the FROR process in 2014. Following the Victorian election and change of government in November 2014, the new Minister for Education reconfirmed the site as surplus and formally referred it to DTF for disposal. DET referred the site to the new FTGLS for rezoning. Given the time that had elapsed, the site was again listed for sale through the FROR process, and Places Victoria (now Development Victoria) submitted an expression of interest. Hobsons Bay Council indicated that it was also interested if Development Victoria did not progress the sale. In 2016, Development Victoria bought the site for $13.875 million, subject to the site being rezoned to a General Residential Zone or Residential Growth Zone by May 2017. The Minister for Planning rezoned the site in January 2017, and the sale was completed. Following settlement, DTF calculated the costs of sale as $14 784, excluding DTF's staff costs. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DET.

Improving the first right of refusal process

Agencies advised they find it difficult to obtain the internal approval necessary to submit an expression of interest within 60 days. Agencies were generally not aware that expressions of interest are not binding and that, after making an expression of interest, they can extend the FROR time frame by agreement.

LUV currently emails the FROR list to agencies as an Excel spreadsheet. LUV does not always receive information about how many agencies expressed an interest in a site or the reasons why agencies were not interested. This makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of the FROR process.

LUV has begun asking agencies to include them in any correspondence relating to an expression of interest, to help develop a dataset over time and identify potential improvements.

LUV plans to improve the accessibility of the FROR process by listing sites on its new Govmap website. This will enable users to view a site's shape, location and adjoining landowners, and register expressions of interest. Usually agencies' asset managers review the FROR list, but Govmap should make it easier for staff in policy or strategy areas or senior departmental officers to engage with the FROR process.

Govmap aims to enable greater automation and efficiency in reporting on the FROR process, as well as enhancing the collection and analysis of data about the FROR process. In turn, this should provide insights that will help LUV to improve Govmap's effectiveness.

LUV is also engaging more proactively with land and policy managers across government, including by performing basic SLUAs to inform agencies of the possible uses of significant or strategic sites listed through the FROR process.

While LUV administers the FROR process, it does not manage the Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines. This limits LUV's ability to implement some improvements to the FROR process, such as extending time frames.

Agencies' compliance with policy

Overall, agencies complied with the FROR process. However, we found two instances where VicTrack's actions were inconsistent.

In one case, VicTrack advertised for public registrations of interest for a Spotswood site a month before the FROR process concluded. Following advice from DTF and VGLM, VicTrack has stated that, in future, it will fully exhaust the FROR process prior to investigating public sale options. In another instance, we did not find evidence that VicTrack had notified agencies about the sale of a site in Sunshine—see Figure 2M. The local council—who was also the tenant—was aware of the sale, however other agencies were not. VicTrack sold the site to a developer for $5.1 million.

Sites purchased by local councils

In addition to outlining the FROR process, the Victorian Government Land Transactions Policy and Guidelines allows landholding ministers to approve land sales to councils with a restriction on the title that limits the council's land use to public or community purposes. VGV's valuation for these sites takes account of this restriction, which lowers the sale price for councils. Since 2014, there have been few sales to councils as part of the FROR process. Examples include DET's sale of part of the former Romsey Primary School site to the Macedon Ranges Shire Council in 2015–16, and Ararat Rural Council, Hindmarsh Council and the City of Darebin purchasing sites from DET in 2016–17. Despite this, councils usually decline the offer to purchase sites, citing lack of funds.

The case study in Figure 2B outlines a sale to a council that occurred outside the FROR process, which illustrates the difficulty of balancing the needs of state and local government in determining the best use of land.

Figure 2B

Case study: Sale of Bob Pettit Reserve, Jan Juc

|

From the 1970s, the government held a site in Jan Juc for a proposed school. The Surf Coast Shire Council had developed a park and sporting facilities on the site, known as the Bob Pettit Reserve. This use of the land was initially an informal arrangement, but it was formalised through a lease in the 1990s. In 2013, demographic analysis of the area by the former Department of Education and Early Childhood Development found that it no longer needed the site. In July 2014, DTF offered the site to the council for $2.2 million—a price that reflects 'restricted community use value' rather than a higher value for residential use. The Surf Coast Shire Council could not purchase the land at this price. Prior to the 2014 election, the then Opposition committed to sell the site to the council for the nominal price of $500 000. This sale was finalised in February 2015. The council has since rezoned the site as public open space and retained it as a park. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DET.

2.5 Reporting landholdings

Under the Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines, agencies must provide evidence justifying the retention of each site they own and they must identify any land that is, or is likely to become, surplus within the next year. A range of sites are excluded from the reporting process, including national and state parks, regional parks and reserves managed by Parks Victoria, and the beds and banks of waterways.

Departments generate landholding reports from their own internal asset management systems. In the past, agencies were required to submit their annual landholding reports to DTF by 1 February. However, from 2017 DTF changed this to 1 December, to allow time for DTF to advise the government on landholdings prior to the completion of the Budget process.

Figure 2C shows Victorian government department landholdings as at 1 February 2017.

Figure 2C

Landholdings by department as at 1 February 2017

Note: 'Land value' refers to book value or fair value, not current market value. Public sector assets are valued for financial reporting purposes on the basis that the land and improvements will remain in government control. The 'land area' figure does not include national and state parks. Whole-of-government landholdings, including national and state parks, are shown in Figure 1A.

Source: VAGO.

DELWP holds the largest area, as it manages numerous Crown land sites. DET holds land with the highest combined value, as a significant proportion of its sites are in urban areas.

DHHS holds a comparatively smaller portfolio because a large number of health‑related sites are managed by separate legal entities—such as DoH, cemetery trusts and hospital boards—and are not included in DHHS's landholdings. There are 4 989 sites controlled by the Secretary of DHHS, and all except 11 are fully utilised and leased to community service providers delivering out-of-home care, disability services and recreation camps.

DTF requires agencies to maintain a minimum level of detail about their land assets, as detailed in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

Minimum dataset requirements for land assets

|

Data type |

Details |

|---|---|

|

Location information |

Land title, address |

|

Site attributes |

Land size, contamination status, current zoning |

|

Ownership and use |

Occupier, current use of site |

|

Value |

Estimated value of the site |

|

Purchase details |

Date and price of the site's purchase |

|

Management/administration |

Details of the agency's internal files or records relating to the site |

|

Assessment and performance information |

Such as the suitability of the site for its current function |

Source: Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines, 2015.

DELWP holds 110 000 parcels of Crown land. Of these, approximately 16 000 are reportable under the Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines, including 15 800 unreserved Crown land sites and 200 former government roads. DELWP is not required to report on reserved Crown land or national parks.

DELWP's ability to report on its landholdings is limited by data gaps and historical limitations in how government has administered Crown land. For example, DELWP estimates that around 10 per cent of its land is comprised of roads, tracks and unreserved allotments, which do not always have accurate records or addresses. Gathering the detailed information the DTF policy requires about these sites would require a significant investment in staff and systems for minimal benefit, as these sites are either unsaleable or low value. However, this should not restrict DELWP from improving the accuracy of its land data.

DELWP is working on the Crown Land Information Improvement Project to improve the accuracy and accessibility of information about its landholdings. As part of this, DELWP is procuring an electronic system to replace its current land information systems. DELWP is also addressing gaps in its data by actively surveying and registering Crown land sites that have never had a formal legal identity, thus expanding the number of individual sites that make up the Crown land estate.

Other landholding departments are also missing some of the information required by DTF, for example, allotment numbers or accurate utilisation statuses. However, these departments have more information than DELWP because they hold fewer individual sites and the majority of these are in 'active' use, so there is sufficient information to identify sites as surplus.

VicTrack

As an OBE, VicTrack is not required to submit annual landholding reports to DTF, unless the Minister for Finance requests one. However, VicTrack has a legislative obligation to maintain accurate land data under the Transport Integration Act 2010.

VicTrack records the utilisation status of its land in a number of internal databases that integrate with its online Railmap system. However, the Railmap system does not record land as 'surplus'—instead, it categorises sites that are not in use for the transport system as 'vacant' or 'leased'. VicTrack's landholdings total 29 690 hectares, of which 20 263 hectares is leased to Public Transport Victoria for transport purposes, 4 598 hectares relates to closed rail lines, and 1 437 hectares is vacant land.

Director of Housing

Like VicTrack, DoH is exempt from providing DTF with annual landholding reports. DoH's portfolio of 64 000 properties is worth approximately $23 billion. DoH has an asset management framework that assigns an 'asset intent' to each property and, like VicTrack's system, it does not use the term 'surplus'. DoH properties are categorised as 'hold and improve', 'redevelop', 'sell, or plan for disposal', and 'review'. DoH records this information on its property management database, the Housing Integrated Information Program.

2.6 Assessing the utilisation status of landholdings

As part of the landholding reporting process, agencies are required to assign a utilisation status to each site they own. The Victorian Government Landholding Policy and Guidelines provides six utilisation categories.

To assign a utilisation status to their land, departments rely on the information they have collected as part of their asset management processes. They export this information from their asset management databases and then apply DTF's utilisation categories.

Figure 2E shows the number of surplus sites agencies identified in 2017.

Figure 2E

Sites categorised as surplus by agencies, 2017

|

Agency |

Total number of sites |

Number of sites categorised surplus |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) |

52 |

0 |

|

DELWP |

15 982 |

17 |

|

DET |

8 844 |

318 |

|

DHHS |

888 |

11 |

|

DJR |

30 |

2 |

|

DTF |

156 |

10 |

|

VicRoads |

2 581 |

45 |

|

Victoria Police |

1 118 |

20 |

|

Total |

29 651 |

423 |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DTF.

However, agencies do not use all six available utilisation categories, nor are the majority of sites even assigned a status, as shown in Figure 2F. Of the 15 992 sites where agencies did not assign a status, 15 965 sites belonged to DELWP.

Figure 2F

Property utilisation statuses as at February 2017

|

Rating |

Definition |

Number of sites |

|---|---|---|

|

5 |

Fully occupied—no portion available for other agency or compatible uses |

10 305 |

|

4 |

Partly occupied—full utilisation included in agency future planning |

3 |

|

3 |

Available for shared occupation—significant portion available for compatible use |

0 |

|

2 |

Vacant with agency utilisation planned—included in agency future planning |

2 880 |

|

1 |

Vacant (and/or used for a community group or for another non‐core business purpose) with no agency utilisation planned—no longer required for agency business |

48 |

|

S |

Declared surplus(a) |

423 |

|

N/A |

Blank field—no category used by agency |

15 992 |

|

Total number of sites |

29 651 |

(a) Eight of these sites have since been sold.

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DTF.

Departments normally use only three of the six available utilisation categories in their annual reports—fully occupied (category 5), vacant with agency utilisation planned (category 2), and declared surplus (category S). Only two DEDJTR sites and one DHHS disability services site were classified 'partly occupied', and none were 'available for shared occupation'. Without more accurate categorisation, government cannot know how much land is partly used, underused or appropriate for shared use.

LUV's new Govmap online tool can show whether a site is under‑utilised, enabling agencies to search for under-utilised sites and explore alternate uses, although this relies on agencies accurately categorising sites as under-utilised.

During this audit, both DET and DELWP discussed the difficulties they face in assigning utilisation statuses to their sites.

DET believes that as its priority is acquiring and maintaining school sites, it is unable to allocate significant resources to assessing the utilisation status of its sites, beyond categorising sites as 'fully utilised' or 'vacant with no agency utilisation planned'. It perceives that the value of doing this is outweighed by other agency priorities.

DELWP has advised that given the scale of its landholdings, conducting a detailed utilisation assessment of every site would not be cost effective. It is easier for other agencies to supply utilisation information because they use most of their landholdings for direct service provision—such as for schools, social housing or transport infrastructure—whereas DELWP holds numerous Crown land sites with limited active use. To address the gaps in its previous landholding reports, DELWP assessed the utilisation status of its sites worth over $500 000—comprising 107 of its 15 982 sites.

While agencies could improve their categorisation of sites, DTF could also improve the category options. Currently there are no options for identifying a site as potentially contaminated or unsaleable due to community sensitivities.

DELWP advised that its annual landholding reports do not show that a large percentage of its land is potentially contaminated. This is partly because there is no category for this, but also because DELWP does not have reliable information. To correct this, DELWP would need to undertake an environmental assessment to confirm the extent of contamination, which would be a significant cost.

DTF has advised that it plans to make a recommendation to Cabinet to change the utilisation categories to reflect a broader range of circumstances.

Reviews of departments' land utilisation

In 2014 and 2017, DTF commissioned external reviews of departments' landholding reports to assess their utilisation categorisation. Both reviews found that departments fully occupied more than 90 per cent of government land for service delivery purposes.

DTF requested that each review investigate whether there were further saleable sites, in addition to those identified by departments. The consultants assessed that departments had categorised some sites as 'fully occupied' but were not using them for 'core services' and, therefore, they might be considered surplus to the agency's requirements. For example, Flemington Racecourse and Luna Park are both owned by DELWP and categorised as fully occupied, but they are not used by DELWP for its own core activities.

The 2014 review identified 71 sites as high value and saleable by 2018. The former Department of Education and Early Childhood Development held 16 of these sites—former schools—and had already declared them surplus, but rezoning was a significant impediment to their sale. Of the remaining sites, some were sold but the majority were not assessed as surplus by agencies, or had significant impediments to sale, such as longstanding community use or leases.

The 2017 review examined how DTF could meet its target of $200 million from the sale of government land. Based on departments' landholding reports, DTF had identified a projected shortfall of $87 million. The consultants identified 49 sites held by departments that would be saleable over the next four years. However, agencies had already identified the majority of these as surplus.

By not determining where sites are under-utilised in line with DTF guidance, agencies are not achieving the best possible value from their land. However, DTF does not provide sufficient guidance on how to differentiate between partly or fully occupied sites, and does not define what attributes a site needs to have to be suitable for shared use.

Assessing future service delivery needs

To mitigate the risk of agencies prematurely selling a site, it is important that they consider their future needs over the next twenty years or more.

In 2015, DET engaged an external consultancy firm to complete a retrospective risk analysis of its land sales to ensure that it considers the full risks of selling a site prior to sale. Broadly, the report found that if the demographic projections for the area indicated that DET would need to re-establish a school within 10 years, it was usually more cost-effective for DET to retain a vacant school site than to purchase a new one. DET now considers projected demographic changes in an area for the next 20 years when deciding whether to retain a site.

VicTrack's Railmap system enables users to review the location, dimensions and land tenure of vacant sites. External users and VicTrack's internal sales development team use Railmap to apply to lease, buy or develop land. VicTrack sends these applications to DEDJTR, which considers long-term strategic transport plans before approving any lease or sale. This effectively mitigates the risk of VicTrack selling land that may be needed for future transport purposes. Figure 2G provides an example of how VicTrack effectively identifies surplus land.

Figure 2G

Case study: Identifying surplus land—Somerville, VicTrack

|

Prior to selling land, VicTrack must confirm whether a site is surplus to future transport requirements by contacting DEDJTR. VicTrack had long held land adjacent to Somerville Station for possible future use. In 2013, DEDJTR determined that VicTrack only needed to retain part of the site. VicTrack subdivided the site, began preparing the surplus part of the site for sale and retained the balance of the site to enable the construction of a second track in the future. VicTrack reconfirmed the approval to sell the site with DEDJTR in 2016, taking a cautious approach to selling the site. VicTrack's decision to subdivide and sell the surplus part of the site is a good example of maximising the value of under-utilised sites. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by VicTrack.

2.7 Strategic Crown Land Assessments

Under the 2016 Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines, agencies must refer all surplus Crown land sites to DELWP for an SCLA. Since 2014, agencies have referred 239 sites to DELWP. Staff in DELWP's regional offices complete SCLAs.

Figure 2H

SCLA process

Source: VAGO based on the Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines, 2016.

As shown in Figure 2H, the key steps are identifying whether a site holds public value and, if it does, recommending mechanisms to protect these values. In some cases, DELWP finds that a particular site has a public value that is so significant that the agency transfers the site to DELWP for retention as part of its Crown land portfolio.

The SCLA process considers public value using a range of criteria, as shown in Figure 2I.

Figure 2I

SCLA considerations for identifying public value

Source: VAGO based on the Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines, 2016.

When completing an assessment, DELWP must only consider values that are 'inherent' to the land itself. Under the current policy, the fact that a community group uses a site is not considered part of its public value—if the community use could take place on another site, then the public value is not inherent to the piece of land. Prior to 2016, the policy allowed for the retention of a site on the basis of community use, which allowed for a broader consideration of Crown land's public value.

Figure 2J provides an example of an SCLA process where public values were identified and the sale could continue providing that the purchaser would protect the public values of the site.

Figure 2J

Case study: Using SCLAs to preserve public land values—Springvale Cemetery

|

DELWP's Knoxfield regional office completed an SCLA for a Crown land site owned by DHHS at Springvale Cemetery within the 90-day time frame. It concluded that the land was of very low public value, apart from recreational and tourism values—the tenant of the site was the Sporting Shooters Association. To protect this public value, the SCLA recommended that DHHS sell the site on the condition that it continue to be used for recreation. In April 2017, DTF sold the site to the Sporting Shooters Association on the basis that it would continue its recreational activities. |

Source: VAGO from information provided by DHHS.

Timeliness of Strategic Crown Land Assessments

The Victorian Government Strategic Crown Land Assessment Policy and Guidelines requires that DELWP complete SCLAs within 90 days. In the past, DELWP has not collected reliable data about the timeliness of the process. However, this has recently changed, and DELWP is planning to dedicate staff to further improve how it monitors the SCLA process.

According to DELWP's data, it has completed the majority of assessments within the required time frame since 2014. However, this figure excludes assessments conducted on DELWP sites.

Between 2014 and 2017, the median time taken to complete an SCLA was 43 days and the longest time was 573 days. While this indicates that DEWLP has usually completed SCLAs on time, the average time taken increased in 2016 and 2017, as shown in Figure 2K.

DEWLP has advised that, at the regional level, there are now fewer resources available to complete SCLAs and this is affecting the time taken to complete assessments. DELWP advises that it does not charge agencies fees to undertake SCLAs, instead absorbing the costs of the process into its current work program.

Figure 2K

Average time taken for DELWP to complete SCLAs, 2014 to 2017

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

Not completing SCLAs within 90 days impedes the preparation of a site for sale. Between May and July 2017, DET submitted 26 sites for SCLAs. By December 2017, DELWP had only completed one.

Some aspects of the SCLA process lack clarity. Agencies are unclear on whether they should request an SCLA before listing a site through the FROR process. LUV internal guidance advises that agencies should request an SCLA prior to the FROR process, but current policies do not specify this. DET has advised that it plans to run the SCLA and FROR processes concurrently, given that both take several months.

Compliance with the Strategic Crown Land Assessment process

During our audit, DELWP indicated that agencies do not always comply with the SCLA policy, which can further delay the sale process. For example, since the 1920s, DET has supported schools running plantations as part of student learning about forestry and the environment. Some schools have recently sought to sell these sites, and DELWP found cases where DET advertised former plantations for sale without requesting an SCLA and without confirming its legal ownership of the sites.

Native title and traditional owner rights

One of the purposes of the SCLA process is to determine the status of native title rights over surplus Crown land. Where an SCLA identifies native title or traditional owner rights, the relevant traditional owner group must agree to relinquish its interest before the sale can progress. Typically, a traditional owner group will receive a community benefit payment in return for relinquishing its rights over a site.

Negotiating with traditional owner groups can slow the preparation of surplus land for sale. This is partly due to the decision-making practices of traditional owners, who often only meet once a month to conduct formal business. The majority of Crown land sites involved in these negotiations are small, low-value sites worth less than $15 000. Given that community benefit payments are usually a percentage of the total value of a site, there is often a low incentive for traditional owners to expedite the process. DTF has sought to address this issue by grouping a number of smaller sites together to negotiate a collective community benefit payment.

DTF is concerned that the native title decision Griffiths v. Northern Territory of Australia (No 3) [2016] FCA 900 will affect future negotiations over Crown land sales. This decision set the percentage of compensation for a traditional owner group at 80 per cent of the freehold value of the relevant sites. On appeal, the court revised this to 65 per cent. Currently in Victoria no more than 50 per cent of the freehold value of a site is paid.

DTF, DJR and traditional owner groups have considered a number of approaches to negotiations in response to the Griffiths v Northern Territory decision, such as introducing a flat rate of compensation for low-value sites or accumulating the value of sites as credit toward the future purchase of a site by traditional owners.

DTF and DJR have agreed to a revised approach to community benefits for traditional owners, where the state pays the costs of sale and DTF pays an additional 10 per cent of the sale price to traditional owners as financial compensation.

Figure 2L shows a case study of the lengthy time lines departments face when preparing sites for sale and negotiating native title.

Figure 2L

Case study: Negotiating native title time lines—DHHS site, regional Victoria

|

A former disability services centre in regional Victoria closed in May 2016, and DHHS referred the site to DTF for sale in March 2017, as part of the DHHS's 2017–18 land sales target. DHHS transferred all paperwork associated with the site in October 2017. VGV valued the site at $1 million. As the site is located in an area subject to a traditional owner settlement agreement, DTF is required to obtain the consent of the traditional owners prior to sale. DHHS is responsible for all site costs until the site is sold. To date, DHHS's landholding costs for this site have been in excess of $50 000 a year, covering security and the fire levy, and maintaining utilities at the site. DTF advised that negotiations over native title rights could take significant time, and it is difficult to estimate when the sale of the site can progress. |

Source: VAGO from information provided by DHHS.

2.8 Rezoning—the Fast Track Government Land Service

FTGLS grew out of an initiative piloted by DET and DELWP in 2013–14 for the rezoning of nine surplus school sites. The rezoning process often caused considerable delays in the sale of former school sites. DET and DELWP arranged for the Minister for Planning—rather than local councils—to process this rezoning, with advice from a new Standing Advisory Committee. The pilot rezoned a number of sites that had been vacant for over a decade, including the former Brandon Park Secondary College, which closed in 2003, and the former Oakleigh South Primary School, which closed in 1999.

Following the 2014 Victorian election, the government expanded this approach to include all government-owned sites, not just former schools. FTGLS ensures that the appropriate planning provisions are in place prior to the sale of government land. FTGLS generally undertakes a public consultation on the proposed planning provisions, to ensure that the minister is able to consider this as part of the decision-making process.

Process and timeliness for rezoning

Since 2015, the Minister for Planning has rezoned 25 sites through FTGLS. DTF refers all its sites to FTGLS for rezoning.

FTGLS advised that it has taken time for some agencies to adjust to the new process, with some submitting incomplete applications when the service started. FTGLS found that the quality of the applications it receives has improved since it introduced new guidance, and it now rarely has to return incomplete applications to agencies.

VicTrack uses a combination of FTGLS and local councils for rezoning. For larger site sales, VicTrack project officers often contact local councils directly, rather than waiting for the council to find out through the emailed FROR listing. Where the local council agrees with the need to rezone the site, VicTrack asks the local council to do the rezoning, as shown in the case study in Figure 2M. There are benefits in choosing different rezoning options depending on the nature of the site and the level of support for the proposed rezoning from the local council.

Figure 2M

Case study: Rezoning using a local council

|

When VicTrack wanted to sell a site in Sunshine, it applied to Brimbank City Council to process a planning scheme amendment to rezone the site from public use to general residential use. VicTrack pursued rezoning through the council, because the council was interested in selling an adjacent site as a joint sale. The council had been leasing the VicTrack site for offices but wanted to break the lease. Brimbank City Council recommended that the Minister for Planning approve the planning scheme amendment, maximising the resale opportunities for the site. |

Source: VAGO from information provided by VicTrack.

Community consultation

The FTGLS process for rezoning usually includes a public exhibition period and hearings. For communities, rezoning is often a key issue in the sale of government land.