Recreational Maritime Safety

Overview

Victoria’s recreational boating industry is important to our economy and to Victorians’ quality of life. In the past five years almost all maritime safety incidents on state waters have involved recreational vessels, and a new marine safety regulatory framework was introduced in 2012 to better manage safety risks.

The framework depends heavily on Transport Safety Victoria's (TSV) effective coordination with voluntary waterway managers and enforcement bodies to maximise duty holders' compliance with their safety obligations. However, TSV cannot demonstrate that it is effectively and efficiently regulating marine safety because it has no framework for reliably evaluating:

- the effectiveness of its regulatory approach, and whether duty holders, waterway managers and enforcement bodies are fulfilling their responsibilities to cost effectively minimise safety risks

- the competence and ongoing suitability of appointed waterway managers, and whether they are actively discharging their voluntary role

- if the state's longstanding waterway rules remain fit for purpose and effective, and support the efficient management of current safety risks

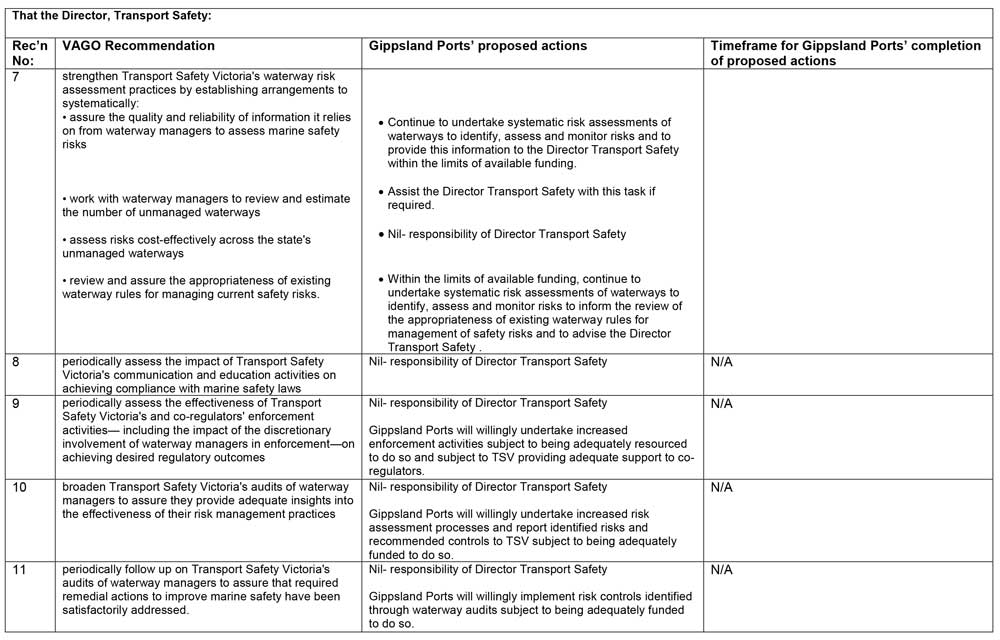

- whether critical information on system-wide marine safety risks and related enforcement strategies is adequately leveraged by TSV, waterway managers and Victoria Police to continuously improve their management of marine safety.

The absence of such arrangements reduces TSV's accountability for performance, and significantly impedes its ability to regulate effectively. Consequently, TSV cannot adequately assure Parliament, the Minister for Ports or the community that its current approach to regulating marine safety is working.

Ongoing concerns about the adequacy of funding to TSV and waterway managers means that the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure—in consultation with the Director, Transport Safety, and central agencies—needs to urgently review and provide assurance about the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for effective implementation of the marine safety regulatory framework.

Recreational Maritime Safety: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2014

PP No 332, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Recreational Maritime Safety.

The audit assessed the effectiveness and efficiency of the state's marine safety regulatory framework in minimising safety risks for recreational maritime uses. It examined the Director, Transport Safety, supported by Transport Safety Victoria (TSV), in his role as the state's regulator of recreational maritime safety and as a waterway manager. It also examined five other waterway managers, the related enforcement activities of Victoria Police, and the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure's (DTPLI) role in coordinating regulatory policy and legislation advice relating to marine safety.

I found that the state's regulatory framework is not being effectively or efficiently implemented. A key shortcoming is the absence of arrangements within TSV for reliably assuring the effectiveness of its regulatory approach, the competence and ongoing suitability of waterway managers, and that longstanding waterway rules remain fit for purpose and support the efficient management of safety risks.

I have made a series of recommendations aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the marine safety regulatory framework. I am encouraged by the Director, Transport Safety's and DTPLI's commitment to implementing actions against these recommendations.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

25 June 2014

Auditor-General's comments

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Steven Vlahos—Sector Director Dr Fei Wang—Team Leader Ray Seidel-Davies—Senior Analyst Michele Lonsdale—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Victoria has approximately 1 200 kilometres of ocean coastline and more than 3 000 square kilometres of inland and enclosed waters. These waters provide Victorians with valuable recreational opportunities that contribute greatly to our quality of life.

In 2012, a new marine safety regulatory framework was introduced to improve the management of safety risks arising from these activities, and from the significant growth in recreational boating, commercial shipping, and newly exposed hazards in inland waterways.

Under this framework, responsibility for managing marine safety is shared between the state's transport safety regulator—the Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director)—designated waterway managers, and a range of other parties collectively known as 'duty holders' on whom the Marine Safety Act 2010 imposes an obligation to manage the safety risks arising from their activities.

My audit has found that the state's regulatory framework is not being effectively or efficiently implemented. Particularly concerning is that despite the framework's intent to improve the management of marine safety risks, its current implementation is dysfunctional.

Specifically, the regulatory framework depends heavily on the Safety Director's effective coordination with waterway managers and enforcement bodies. However, this is not currently being achieved. None of the examined waterway managers had established arrangements to systematically identify and, where relevant, manage safety risks on all waters under their control. Additionally, most waterway managers had not exercised their option to enforce marine safety laws because of their limited resources. Further, the Safety Director has no arrangements to systematically engage with waterway managers to share risk information and coordinate their enforcement strategies with his own and those of Victoria Police.

I also found that the Safety Director cannot demonstrate that he is effectively and efficiently regulating marine safety as he has no framework for assessing the impact of his regulatory approach, including performance of related parties in minimising safety risks.

These shortcomings are significant as they reduce the Safety Director's accountability for performance and impede his capacity to effectively regulate the marine safety system. They also highlight a need for my office to further examine the Safety Director's wider duties of regulating rail and bus safety when determining my future audit priorities.

I have made a number of recommendations for addressing these issues, which pleasingly the Safety Director and examined agencies have accepted. In particular, the recommendations reinforce the need for the:

- Safety Director to regularly assess and report on the performance of Victoria's marine safety system, and to use this information for targeting his regulatory activities

- Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, in consultation with the Safety Director and central agencies, to urgently review the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for supporting effective implementation of the regulatory framework.

I would like to thank the staff of Transport Safety Victoria, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Parks Victoria, Goulburn Murray Rural Water Corporation, Gippsland Ports Committee of Management, Gannawarra Shire Council and Victoria Police for their assistance and cooperation during this audit.

I look forward to receiving updates from them in implementing the recommendations.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

June 2014

Audit Summary

Audit summary

The marine industry is vital to Victoria's economy, contributing around $4.5 billion per year and employing over 7 000 people in manufacturing, wholesaling and retailing. Water-based recreational activities also contribute greatly to Victorians' quality of life.

However, the growing popularity of these activities, coupled with the significant scale and, in some cases, remoteness of state waters highlights both the challenge and need for the state to effectively manage the associated safety risks.

Over the five years to 2012–13, almost all maritime safety incidents on state waters have involved recreational vessels only—approximately 97 per cent. While the numbers of fatalities and serious injuries have been relatively stable over this period—averaging around five and 24 per year respectively—the aggregate number of recreational marine incidents increased from 1 084 to 1 341, or by 24 per cent.

The Marine Safety Act 2010 (the Act) and the Marine Safety Regulations 2012 (the Regulations) provide for safe marine operations in Victoria by prescribing requirements for vessel registration, operation, safety equipment, licensing of operators and enforcement of safety standards.

The Act and the Regulations came into operation on 1 July 2012, replacing the former Marine Act 1988 and Marine Regulations 2009, with the aim of improving the management of marine safety risks.

The Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director), supported by Transport Safety Victoria (TSV), is the state's regulator of transport safety. The Act establishes that the responsibility for managing marine safety is shared between the Safety Director, designated waterway managers and a range of other parties collectively known as 'duty holders' on whom the Act imposes an obligation to manage the safety risks arising from their activities. Key duty holders include port management bodies and members of the public who participate in maritime activities, as well as the suppliers and operators of vessels and equipment used for such activities.

The audit assessed the effectiveness and efficiency of the state's marine safety regulatory framework in minimising safety risks for recreational maritime uses. The audit examined TSV in its role as the state's regulator of recreational maritime safety and as a waterway manager, as well as five additional waterway managers including the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), Parks Victoria, Goulburn‑Murray Rural Water Corporation, Gippsland Ports Committee of Management and Gannawarra Shire Council.

The audit also examined the related enforcement activities of Victoria Police, and the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure's (DTPLI) role in advising on regulatory policy and legislation relating to maritime safety.

Conclusions

The state's regulatory framework for minimising marine safety risks is not being effectively or efficiently implemented.

The framework depends heavily on TSV's effective coordination with voluntary waterway managers and enforcement bodies to maximise duty holders' compliance with their safety obligations. However, it is not evident that this is being achieved as TSV cannot demonstrate that it is effectively and efficiently regulating marine safety. This is because it has no framework for reliably evaluating:

- the effectiveness of its regulatory approach, and whether duty holders, waterway managers and enforcement bodies are fulfilling their responsibilities to cost‑effectively minimise safety risks

- the competence and ongoing suitability of appointed waterway managers, and whether they are actively discharging their voluntary role

- if the state's longstanding waterway rules remain fit for purpose, effective, and support the efficient management of current safety risks

- whether critical information on system-wide marine safety risks and related enforcement strategies is adequately leveraged by TSV, waterway managers and Victoria Police to continuously improve their management of marine safety.

The absence of such arrangements reduces TSV's accountability for performance, and significantly impedes its ability to effectively regulate. Consequently, TSV cannot adequately assure Parliament, the Minister for Ports or the community that its current approach to regulating marine safety is working.

Ongoing concerns about the adequacy of funding to TSV and waterway managers means that DTPLI, in consultation with the Safety Director and central agencies, needs to urgently review and assure the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for supporting effective implementation of the marine safety regulatory framework.

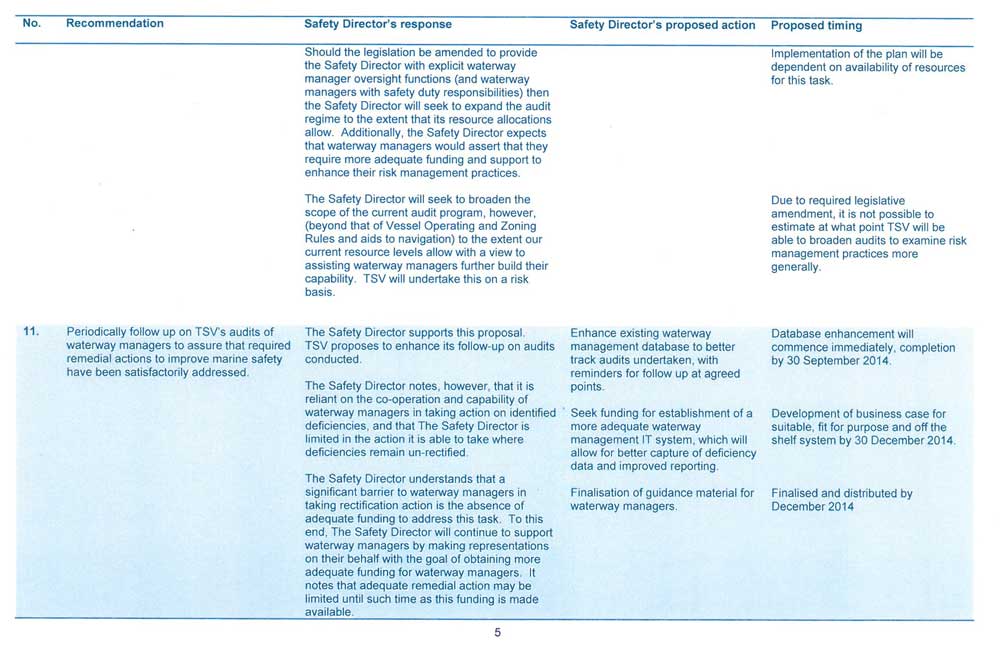

Findings

Monitoring the marine safety system

System-wide monitoring arrangements

A key object of the Act is to promote the effective management of safety risks. The Safety Director, supported by TSV, has a range of statutory functions that create a strong imperative for monitoring the performance of the marine safety system in achieving this object. These include:

- monitoring compliance with marine safety laws

- making appropriate waterway rules

- developing and enforcing appropriate standards for navigation, maritime safety and related infrastructure

- coordinating and supporting the effective implementation of enforcement by members of the police force, transport safety officers and waterway managers.

While the Safety Director has no explicit function under the Act to oversee waterway managers, the state's 2009 review of the former Marine Act 1988 recognised that the above functions nevertheless require the Safety Director to exercise a level of oversight. However, TSV's existing monitoring arrangements do not enable the Safety Director to assess whether all of these functions are being effectively carried out.

TSV has procedures in place for auditing waterway managers and reporting on marine incidents, but there are no defined performance targets or documented arrangements for monitoring, assessing and reporting on the effectiveness of the wider marine safety system.

This information is needed urgently to enable TSV to focus and prioritise its regulatory activities, as this audit has identified critical shortcomings in risk management, safety controls and agency coordination in promoting and enforcing compliance with marine safety laws.

In October 2013, TSV started work to establish a more comprehensive framework to benchmark its regulatory performance through measuring the costs and benefits of its regulatory work, along with its efficiency and effectiveness. However, it has not set a time frame to complete this work.

Funding arrangements for marine safety management

TSV and waterway managers have consistently identified the lack of funding as a critical issue that impedes their ability to effectively regulate marine safety. TSV has also indicated that, based on its experience, the capacity and willingness of waterway managers to discharge their statutory functions is directly proportional to their allocated funding, which in most cases is minimal.

Notwithstanding this, shortcomings in TSV's performance monitoring mean that it cannot demonstrate that its existing regulatory resources are being effectively applied.

The funding for recreational maritime safety is derived from state appropriations that can include fees charged for licensing recreational operators and the registration of their vessels. The Act, consistent with the former Marine Act 1988, establishes that all prescribed revenue from these fees must be used for boating and related safety programs.

The revenue collected from these fees forms part of the state's consolidated revenue administered by the Department of Treasury and Finance and is allocated through the annual Budget process.

Although the Regulations prescribe only registration revenue for these purposes, the DTPLI advised that the manner in which it has previously recorded the use of these revenues has encouraged a misconception that licensing revenue must also be used for boating facilities and related safety programs.

Consequently, we found that DTPLI records do not provide sufficient information to reliably acquit the use of registration fee revenues.

DTPLI records indicate that approximately $103 million of the $201 million in licensing and registration fee revenue collected from the sector between 2001–02 and 2012–13 was from registration fees, and that total allocations to enforcement activities and from the Boating Safety Facilities Program (BSFP), during this period amounted to $10.8 million and $56.5 million respectively.

However, DTPLI advised that it cannot confirm the difference between fee revenues collected from and expended in the sector. This is because its records are based on an assumed, notional allocation of these fees to its related programs, given that they are not separately identified in annual appropriations received through the Budget process.

Notwithstanding this, DTPLI advised that the state's expenditure in the marine sector over this period has exceeded fee revenues collected when annual expenditure via the BSFP and its Local Ports Program is considered. While it is evident that this expenditure has occurred and exceeds annual revenues from registration fees, DTPLI acknowledges that it cannot formally acquit that all registration revenue has been fully expended in accordance with the Act.

A February 2011 briefing from the former Department of Transport to the then Minister for Ports advised of a discrepancy between revenue collected and revenue allocated to the marine sector from the Consolidated Fund.

The then Minister for Ports wrote to the then Treasurer highlighting the funding challenges faced by local ports. He also signalled his intention to seek government approval to allocate all boating registration and licensing fee revenues from 2011–12 to the BSFP and Local Ports Program, which both support recreational boating.

DTPLI advised that this proposal was not supported, and it therefore did not proceed for consideration by government.

This situation, coupled with the deficiencies in statewide risk management and performance monitoring, means that there is insufficient assurance that available fee revenue is being effectively and efficiently applied across the marine safety system to manage risks.

Identifying and managing safety risks

Transport Safety Victoria's oversight of statewide risks

As the state's transport safety regulator, the Safety Director needs to assure the effective management of safety risks on all state waters, including those without a designated manager. TSV's legal advice is that the Act does not explicitly mandate this or require the Safety Director to become the 'default' waterway manager in such circumstances. Nevertheless, in a purely operational sense the Safety Director needs to understand the nature of prevailing safety risks across the state's waterways in order to assess the level and nature of his shared responsibility under the Act to control, eliminate or mitigate them.

Although TSV has developed a conceptually sound risk assessment tool, its implementation is compromised by key information gaps and an over-reliance on the deficient risk management practices of most waterway managers. Administering the tool is also resource intensive as it requires TSV to manually compile and maintain a large volume of data for all of the state's 184 managed waterways.

A key shortcoming is that the tool does not adequately consider the risks across the state's unmanaged waterways. These shortcomings mean TSV cannot be confident it accurately understands the nature or severity of all marine safety risks across the state. TSV advised it intends to address this issue.

Waterway managers' oversight of local risks

Waterway managers also need to accurately understand the nature and severity of prevailing safety risks on waters under their control so as to assess their consequential impact, if any, on their shared responsibility to manage them.

However, none of the waterway managers we examined had established arrangements to systematically identify, assess and monitor all safety risks on all waters under their control. Consequently, none could fully demonstrate that all of their safety controls and recreational waterway users comply with the Act and the Regulations and that safety risks are being effectively managed.

Parks Victoria and the Gippsland Ports Committee of Management had identified and assessed the safety risks for local ports they manage under the Port Management Act 1995 and events on high-risk waterways managed under the Act. However, it was not evident that they had done the same for all of the other non-port-related waterways in their control under the Act, which they advised was due to there being no designated funding.

TSV's audits of 82 waterways over a three-year period to 2013 found 85 per cent of navigational aids and signage at these waterways did not comply with applicable requirements—for example, buoys and safety signage were in the wrong location, signage was incorrect or missing. TSV highlighted that this was in part because waterway managers did not have sufficient resources or the required capabilities to effectively discharge these functions.

Setting and maintaining waterway rules

Under the Act, the Safety Director has the power to make waterway rules that regulate or prohibit the operation of any vessel, or use of state waters by any person. These rules form a vital part of the control framework for managing recreational maritime safety risks and typically prescribe a range of matters, such as speed limits and areas where vessels and recreational users are prohibited.

Most of the state's existing waterway rules were set under the former Marine Act 1988. Since that time it is possible that many waterways, particularly inland rivers and lakes, have changed substantially in their usage and associated risk profile due to such circumstances as flooding, drought and population change. However, it is not evident that either TSV or waterway managers systematically review the appropriateness of waterway rules.

Consequently, there is little assurance that all existing rules adequately address current safety risks.

Promoting and enforcing compliance with regulatory requirements

Promoting voluntary compliance

TSV has targeted its education and communication activities based on known safety risks but has not yet rigorously evaluated their impact on improving recreational users' behaviour and compliance. Encouragingly, some of the waterway managers examined and Victoria Police have also undertaken education activities, but the impact of these has similarly not yet been assessed.

Consequently, there is little evidence that TSV, waterway managers and Victoria Police are working effectively as part of an integrated system of co‑regulators to promote compliance with safety obligations and minimise related risks.

TSV advised that it acknowledges the importance of evaluation but that it is highly dependent on limited and contestable grants from DTPLI's BSFP for education activities, which limits its capacity to undertake evaluations.

Enforcing compliance

The Act required TSV to develop a Marine Enforcement Policy within 12 months of the Act becoming operational and to consult with relevant stakeholders, including those parties involved in jointly enforcing compliance. Whilst TSV undertook limited consultation with Victoria Police, the Boating Industry Association of Victoria and Parks Victoria, it did not actively consult with the majority of other waterway managers. This shortcoming means TSV cannot be confident that all waterway managers adequately understand their related roles, including how they can use enforcement options to support their role in regulating boating activities and events on their waterways.

While past TSV enforcement activities have been risk-based, targeted and coordinated with those of Victoria Police, there are critical weaknesses that undermine its general approach. These include:

- concerns with the quality and reliability of data underpinning risk assessments

- no arrangements for assuring effective cross-agency coordination

- enforcement outside of high-use locations is limited

- no assessments of the efficiency and effectiveness of enforcement activities.

These weaknesses mean that TSV cannot demonstrate or be confident that current approaches to enforcement by responsible agencies are adequately coordinated, efficient and effective in achieving compliance with marine safety laws.

Weaknesses with TSV's cross-agency coordination mean that Victoria Police's current risk assessments are not informed by systematic input from all waterway managers and TSV on the status of current and emerging safety risks across all managed waterways. Victoria Police acknowledges that enhanced access to and coordination of risk information from waterway managers could assist its targeting of related enforcement activities.

Most waterway managers do not exercise their option to enforce marine safety laws because of their limited resources. However, TSV does not assess whether or not this lack of enforcement is compromising the effective discharge of waterway manager functions, including management of safety risks.

Assessing waterway managers' compliance

TSV's audits of waterway managers do not extend to systematically assessing the effectiveness of their risk management practices. Instead, such assessments are typically gleaned through ad hoc interactions with waterway managers or following safety incidents. Consequently, TSV's audits do not provide adequate insights into the effectiveness of waterway managers.

Supporting waterway managers

Assessing the capabilities of waterway managers

TSV has not determined the key capabilities required by waterway managers to carry out their legislative responsibilities, nor formally assessed the skills and knowledge of current waterway managers against those capabilities. Similarly, no assessment has been made of the ongoing suitability of previously appointed waterway managers, even though the majority of them have been in the role since 1988.

TSV's legal advice states that the Act does not prescribe explicit capability criteria for waterway managers. This, however, does not preclude TSV, in consultation with DTPLI, from developing a capability framework to inform current support to waterway managers, and any related recommendations to the Minister for Ports.

Changes in local conditions since 1988 mean that the synergies that existed previously with respect to the core responsibilities of some waterway managers may no longer exist.

TSV advised that due to the Safety Director's independence, its role in informing the decisions of the Minister for Ports on the appointment and/or reappointment of waterway managers is not clearly defined. Notwithstanding this, the Transport Integration Act 2010 empowers the Safety Director to make recommendations to the minister on the operation, administration and enforcement of the Marine Safety Act 2010 and associated Regulations. Better knowledge of waterway manager capabilities could therefore inform any related recommendations from the Safety Director to the minister. It would also aid TSV's targeting of its current support activities to waterway managers. The current lack of periodic reviews of waterway managers' capabilities means that TSV has limited insight into the nature or extent of any capability gaps among current managers or whether they should be continuing to perform that role.

We found that five waterway managers who had either resigned or intended to resign had done so in part because they did not perceive that the role aligned with their organisation's core functions.

DEPI similarly advised at the commencement of this audit that it no longer acknowledged or discharged its waterway manager functions—even though it is the declared manager for 36 of the state's waterways—because it no longer considered that it was the most suitable body to perform the role. Consequently, we found that DEPI has generally not responded to TSV's correspondence on the results of 11 audits it undertook of DEPI's waterways between 2008 and 2011. TSV advised that it was aware of DEPI's view and that it has worked to support it to continue in the role.

TSV also advised that, given its current resource constraints, it believes it is better to have a waterway managed by a local waterway manager even if they are only capable of undertaking a subset of the waterway manager functions.

These circumstances highlight a need for TSV to adopt a more proactive approach to systematically assuring and advising the Minister for Ports on the suitability and competence of declared waterway managers.

Providing guidance and training

TSV's guidance and training to waterway managers has been developed largely in response to their requests. However, TSV has not complemented this reactive approach with more targeted training based on a holistic assessment of waterway managers' capability gaps and needs. Therefore, TSV cannot be certain that it is making best use of its limited resources to effectively prioritise the content and timing of its support to waterway managers.

Recommendations

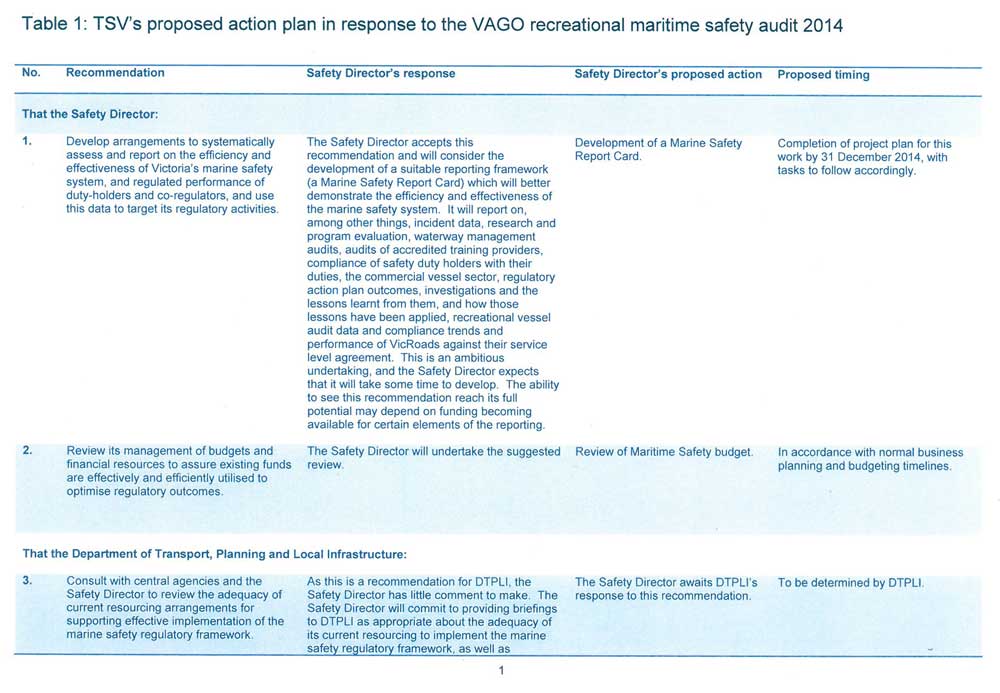

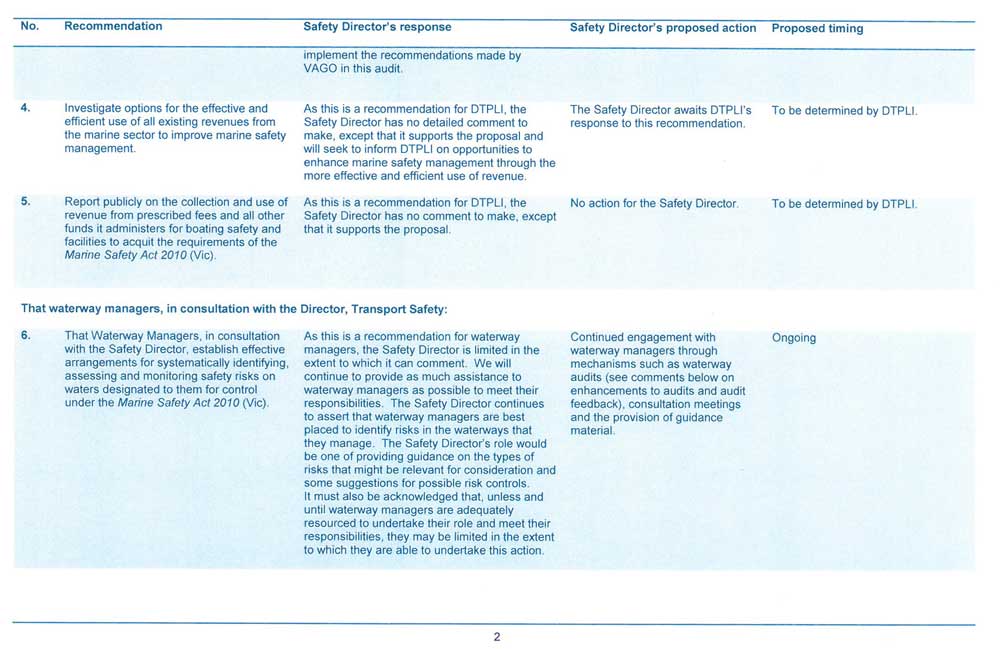

That the Director, Transport Safety:

- develops arrangements to systematically assess and report on the efficiency and effectiveness of Victoria's marine safety system, and related performance of duty holders and co-regulators, and uses this data to target regulatory activities

- reviews management of budgets and financial resources to assure existing funds are effectively and efficiently utilised to optimise regulatory outcomes.

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure:

- consults with central agencies and the Director, Transport Safety, to review the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for supporting effective implementation of the marine safety regulatory framework

- investigates options for the effective and efficient use of all existing revenues from the marine sector to improve marine safety management

- reports publicly on the collection and use of revenue from prescribed fees and all other funds it administers for boating safety and facilities to acquit the requirements of the Marine Safety Act 2010.

That waterway managers, in consultation with the Director, Transport Safety:

- establish effective arrangements to systematically identify, assess and monitor safety risks on waters designated to them for control under the Marine Safety Act 2010.

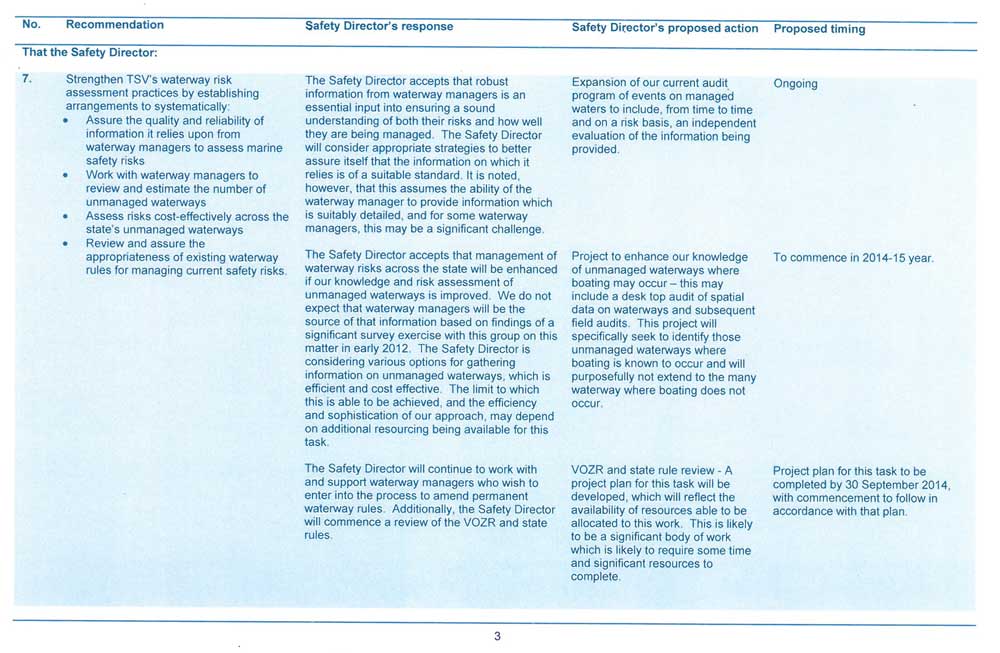

That the Director, Transport Safety:

- strengthens Transport Safety Victoria's waterway risk assessment practices by establishing arrangements to systematically:

- assure the quality and reliability of information it relies on from waterway managers to assess marine safety risks

- work with waterway managers to review and estimate the number of unmanaged waterways

- assess risks cost-effectively across the state's unmanaged waterways

- review and assure the appropriateness of existing waterway rules for managing current safety risks.

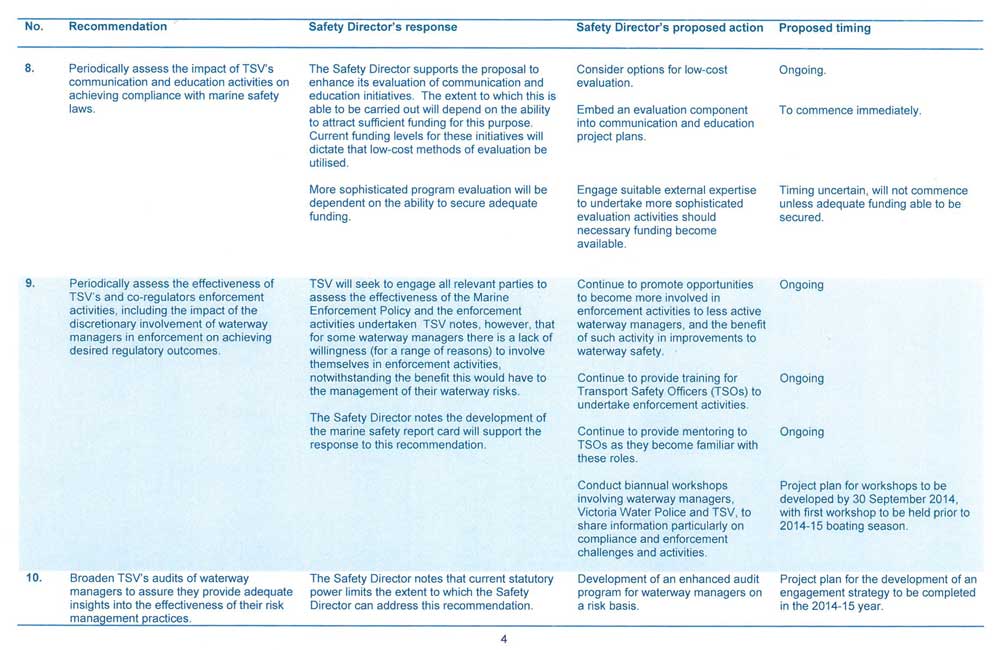

- periodically assesses the impact of Transport Safety Victoria's communication and education activities on achieving compliance with marine safety laws

- periodically assesses the effectiveness of Transport Safety Victoria's and co-regulators' enforcement activities—including the impact of the discretionary involvement of waterway managers in enforcement—on achieving desired regulatory outcomes.

That the Director, Transport Safety:

- broadens Transport Safety Victoria's audits of waterway managers to assure they provide adequate insights into the effectiveness of their risk management practices

- periodically follows up on Transport Safety Victoria's audits of waterway managers to assure that required remedial actions to improve marine safety have been satisfactorily addressed.

That the Director, Transport Safety, in consultation with the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure:

- defines the minimum competencies and capabilities of waterway managers

- implements a waterway manager capability framework that includes periodic assessments of capability gaps to better inform provision of support to waterway managers

- uses the insights from these assessments to provide advice to the Minister for Ports on the appointment and/or reappointment of waterway managers.

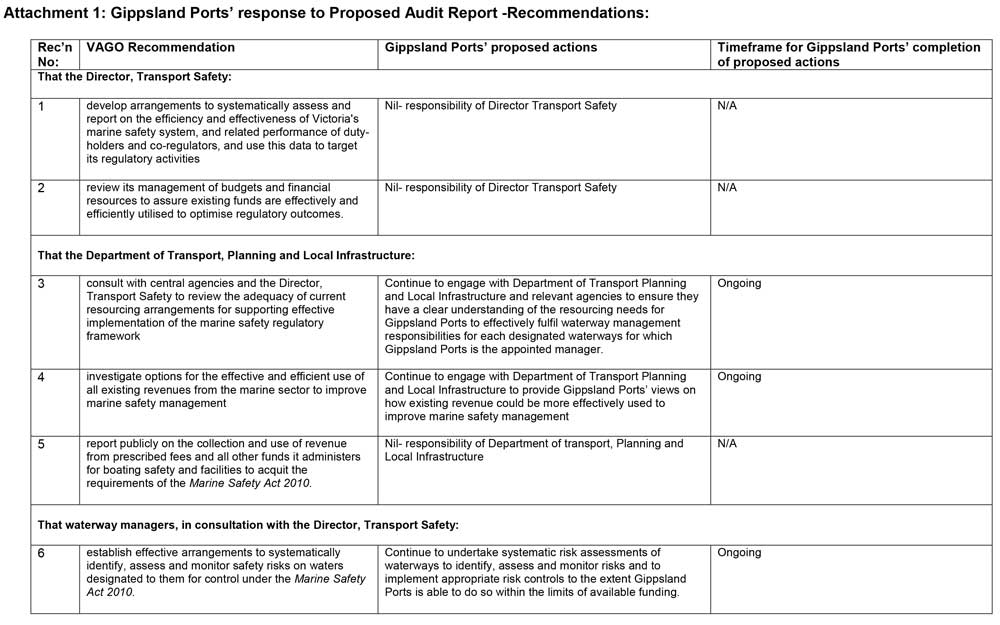

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to Transport Safety Victoria, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure, the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Parks Victoria, Gippsland Ports, Goulburn‑Murray Rural Water Corporation, Gannawarra Shire Council and Victoria Police with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The marine industry is vital to Victoria's economy—contributing around $4.5 billion per annum and employing more than 7 000 people in manufacturing, wholesaling and retailing.

Victoria has approximately 1 200 kilometres of ocean coastline and more than 3 000 square kilometres of inland and enclosed waters. These waters provide Victorians with valuable water-based recreational opportunities that contribute greatly to quality of life.

Over the five years to June 2013, the number of registered recreational vessels in Victoria—comprising powered vessels such as cabin cruisers, houseboats, jet skis and motorised yachts—has steadily increased from around 161 600 in 2008–09 to 172 700 in 2012–13, or by 7 per cent. Jet skis represented the biggest growth in registration numbers over this period—43 per cent. The number of unpowered and, therefore, unregistered recreational vessels such as kayaks, canoes and paddleboats is currently estimated to be 40 000. At June 2013, around 277 300 people were licensed to operate a recreational vessel.

Photograph courtesy of Crok Photography/Shutterstock.

Significant growth has also occurred in international shipping, and interstate and intrastate commercial shipping since the former Marine Act was enacted in 1988. Over the same period, the prolonged drought led to the shrinking of some inland waterways, creating safety risks from newly exposed waterway hazards.

1.2 The marine safety regulatory framework

1.2.1 Review of marine safety regulation

In November 2008, the former Department of Transport commenced a review of the then Marine Act 1988 aimed at improving the management of waterway resources and safety associated with commercial and recreational maritime activities. This review was informed by extensive public consultation including engagement with key industry and user groups. At that time there was a concern that the Marine Act 1988 did not adequately address marine safety risks arising from the growth in recreational boating and commercial shipping, and the newly exposed hazards in inland waterways.

The Marine Act 1988 was subsequently replaced by the Marine Safety Act 2010 (the Act) and Marine Safety Regulations 2012 (the Regulations) which both became effective on 1 July 2012.

1.2.2 Objects and principles of the regulatory framework

The objects of the Act include promoting:

- the safety of marine operations

- the effective management of safety risks

- continuous improvement in marine safety management

- public confidence in the safety of marine operations.

The Act establishes that responsibility for managing marine safety is shared between the regulator—the Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director)—waterway managers, and a range of other parties collectively known as 'duty holders' on whom the Act imposes an obligation to manage the safety risks arising from their activities. Key duty holders include port management bodies and members of the public who participate in maritime activities, as well as the suppliers and operators of vessels and equipment used for such activities.

The Act imposes different safety obligations on duty holders that reflect the nature of the risk the party creates through their activities and their capacity to manage it. For example, vessel operators must take reasonable care for their own and passenger safety, passengers must not place the safety of another person on board at risk, manufacturers must ensure a vessel is safe if it is used for the purpose for which it was designed and port management bodies such as Port of Melbourne Corporation must ensure the safety of marine safety infrastructure operations.

The Regulations are similarly focused on ensuring safe marine operations by prescribing the requirements for key aspects—including vessel registration, operation, equipment, the licensing of operators and enforcement of related safety requirements.

The Act and the Regulations also introduced:

- greater criminal sanctions in cases where a vessel causes death or serious injury

- new powers for Victoria Police and authorised transport safety officers (TSO) to seize, impound and seek forfeiture of vessels to enforce compliance with safety legislation and waterway rules.

1.2.3 Institutional responsibilities

Under the Transport Integration Act 2010, the Safety Director, supported by Transport Safety Victoria (TSV), is the state's safety regulator for rail, bus and maritime transport. Several other agencies are also responsible for administering the Act and Regulations, including port management bodies, local port managers, waterway managers and Victoria Police. Except for Victoria Police, these agencies also have the option to enforce the Act through the appointment of transport safety officers (TSO) authorised by the Safety Director.

Transport Safety Victoria

As the state's transport safety regulator, the Safety Director through TSV:

- licenses, registers and accredits operators and other industry participants

- promotes awareness about marine safety issues and obligations

- monitors duty holders' systems for managing safety risks

- monitors compliance with marine safety legislation

- develops waterway rules, marine safety standards and codes of practice for managing and minimising safety risks

- takes enforcement action as appropriate to promote marine safety outcomes.

TSV therefore has a key role to provide guidance to waterway managers, and to educate duty holders on their related obligations. Although not an explicit requirement under the Act, TSV needs to assure that they effectively administer their statutory responsibilities so as to assess the nature and level of its shared responsibility under the Act to manage any residual safety risks arising.

Photograph courtesy of Jo Chambers/Shutterstock.

Commercial and local port managers

Under the Port Management Act 1995 (PMA), commercial and local port managers' functions are directed at providing a safe marine environment. Their functions for managing marine safety under the PMA are consistent with, and in some cases more extensive than, those under the Act. For example, a port manager's functions include providing, developing and maintaining port facilities—such as jetties, boat ramps, moorings and vehicle parks.

Waterway managers

Under the Act, the Minister for Ports may declare any agency to be a waterway manager—subject to the agency's agreement—to provide for and manage the safe operations of vessels in waters under its control.

Several agencies are currently appointed as waterway managers, including departments and statutory authorities, local governments, water corporations and committees of management. Almost all of the current waterway manager appointments were made in 1988 under the former Marine Act 1988.

Waterway managers fulfil their responsibilities under the Act primarily by:

- managing key infrastructure such as moorings, berths, channels, navigation aids and safety signage in accordance with standards set by the Safety Director

- making and assuring compliance with safety rules such as vessel exclusion zones and speed limits in waters under their control.

Waterway managers can also elect to exercise enforcement powers through the deployment of TSOs authorised by the Safety Director.

The voluntary nature of the waterway manager role means it is necessary for TSV to adopt a more cooperative and collaborative approach to waterway management and regulation. This is in order to maximise voluntary input to support improved risk management, safety and ongoing provision of recreational boating opportunities to Victorians. While the waterway manager's role is voluntary, the majority of waterway managers use paid employees to undertake related tasks.

The Act imposes a limited and tailored set of statutory obligations on waterway managers, revolving mainly around the need to comply with standards for navigation aids and dredging. It also indemnifies waterway managers against any liability arising from performing their functions in good faith. Consequently, as there are no offences or breaches for waterway managers under the Act, TSV has limited recourse to undertake any punitive action if a waterway manager is not meeting its responsibilities and therefore must primarily rely on their goodwill and active cooperation.

There are currently 56 waterway managers responsible for the state's 184 managed waterways. The Safety Director is also a waterway manager for 12 waterways.

As the state's transport safety regulator, the Safety Director needs to assure the effective management of safety risks on all state waters including those without a designated manager. The Act does not explicitly mandate this or require the Safety Director to become the 'default' waterway manager in such circumstances. Nevertheless, the Safety Director needs to understand the nature of prevailing safety risks across the state's waters in order to assess the level and nature of his shared responsibility under the Act to control, eliminate or mitigate them.

TSV advised that it is not possible to definitively know the exact number of unmanaged waterways across the state due to the changing nature of waterways, which are impacted by climatic conditions such as drought and snow run-off, and events such as water extraction for irrigation purposes. However, if TSV considers that an 'unmanaged' waterway presents unreasonable risks to the public, it can advise the minister to appoint a manager for it.

Figure 1A

Number of managed waterways, by entity

|

Type of entity |

Number of waterways |

|---|---|

|

Statutory authorities—e.g. Parks Victoria, TSV, water corporations |

61 |

|

Department of Environment and Primary Industries |

36 |

|

Local government |

61 |

|

Committees of management |

22 |

|

Other—e.g. Hazelwood Power Corporation Ltd |

4 |

|

Total |

184 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police supports the regulatory framework through its enforcement activities, and its Water Police operations provide search and rescue services where required on Victorian waters. It also coordinates emergency responses to all marine incidents throughout Victoria involving recreational and commercial vessels.

Other agencies

Other agencies involved in recreational maritime safety include:

- The Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) is responsible for coordinating the development of regulatory policy and advice on legislation relating to the transport system and related matters. It therefore has a leadership role in developing and monitoring marine safety policy and legislation and the associated regulatory framework.

- VicRoads manages the marine licensing and vessel registration processes under a service agreement with TSV.

1.3 Trends in recreational marine safety incidents

Over the five years to 2012–13, almost all maritime safety incidents on state waters have involved recreational vessels only—approximately 97 per cent. While the numbers of fatalities and serious injuries have been relatively stable over this period—averaging around five and 24 per year respectively, data compiled by TSV shows that the aggregate number of recreational marine incidents increased from 1 084 to 1 341, or by 24 per cent. The main types of incidents were vessel disablement and requiring assistance (83 per cent), followed by grounding (5 per cent), capsizing (3 per cent) and people in trouble such as person overboard (3 per cent).

It is difficult to identify growth in safety incidents relative to the number of vessels in use, as the number of unregistered vessels involved in reported safety incidents is not known. It is also difficult to use incident data as a measure of the level of marine safety risk due to significant under-reporting of incidents. Notwithstanding this, the growing popularity of recreational boating reflected in the increasing number of registered recreational vessels and aggregate incidents indicates a growing risk.

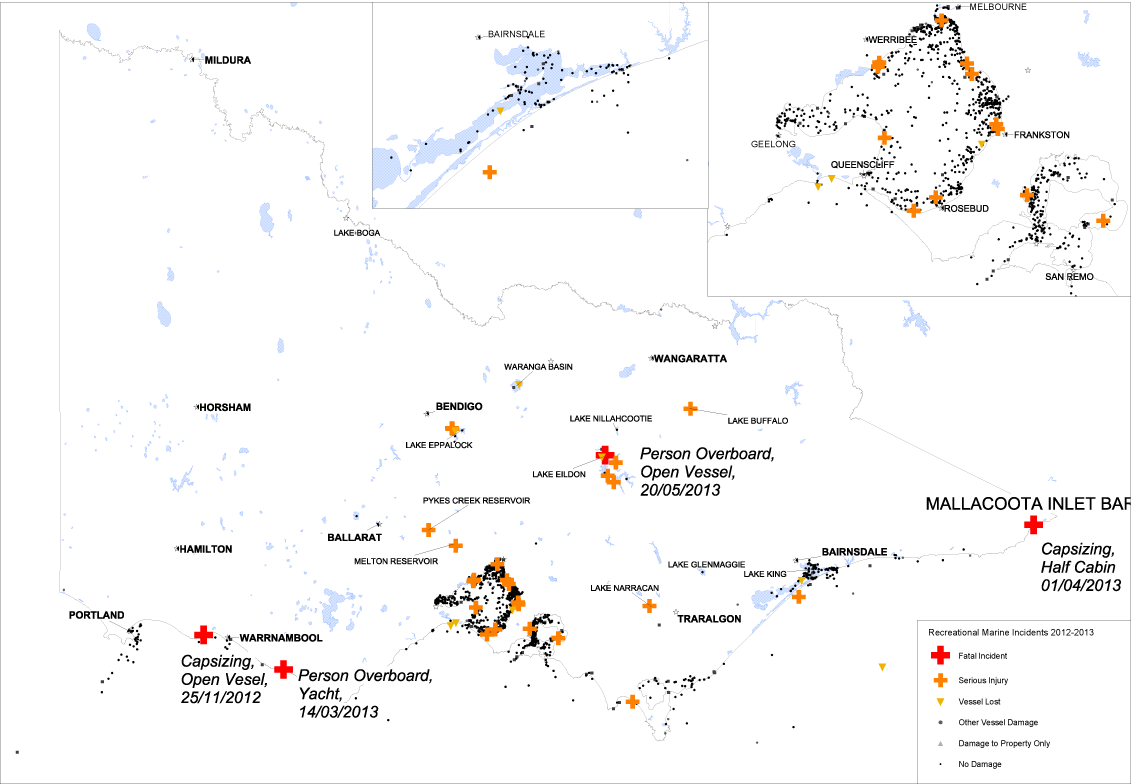

Figure 1B shows that around 90 per cent of safety incidents have occurred on Port Phillip and Western Port bays.

Figure 1B

Recreational marine incidents, 2012–13

Source: Transport Safety Victoria.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the state's marine safety regulatory framework in minimising safety risks for recreational maritime uses.

The audit examined TSV in its role as the state's regulator of recreational maritime safety and as a waterway manager. A sample of five additional waterway managers was also examined—Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Parks Victoria, Goulburn-Murray Rural Water Corporation, Gippsland Ports Committee of Management and Gannawarra Shire Council.

Collectively, the six waterway managers are responsible for 47 per cent of Victoria's 184 managed waterways, including all waterways where the level and nature of existing recreational use poses a high risk to safety. Figure 1C provides an overview of the audited waterway managers.

Figure 1C

Overview of audited waterway managers

|

Waterway manager audited |

Number of waterways and key characteristics |

|---|---|

|

Parks Victoria |

Three rivers, two lakes, an area of Bass Strait and the three local ports of Port Phillip, Western Port—the state's two most popular ports—and Port Campbell. |

|

Department of Environment and Primary Industries |

Thirty-six inland rivers/lakes located across the state. |

|

Gippsland Ports |

Seven waterways including the five local ports of Corner Inlet and Port Albert, Port of Gippsland Lakes, Port of Anderson Inlet, Port of Snowy River and Port of Mallacoota Inlet. |

|

Goulburn-Murray Rural Water Corporation |

Fourteen water storage areas holding 70 per cent of Victoria's stored water, some of which are also popular for recreational activities, such as Lake Eildon. |

|

Gannawarra |

Three lakes and one creek, including Lake Charm where statewide ski racing competitions are held. |

|

Transport Safety Victoria |

Twelve waterways, including many popular areas such as Anglesea and Torquay along Bass Strait. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DTPLI's role in coordinating the development of regulatory policy and legislation advice relating to maritime safety was also examined.

The audit also examined how the related enforcement activities of Victoria Police were informed by and aligned with TSV's regulatory framework.

The audit did not examine the management of commercial maritime safety risks and the associated role of port management bodies, as this is regulated by the Commonwealth Government.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit used desktop research, document and file reviews, and interviews with agency staff and stakeholders.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $505 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 assesses TSV's overall approach to monitoring the marine safety system

- Part 3 examines the identification and management of marine safety risks

- Part 4 examines approaches to achieving compliance with regulatory requirements, including enforcement activities

- Part 5 examines support provided to waterway managers to fulfil their regulatory responsibilities.

2 Monitoring the marine safety system

2 Monitoring the marine safety system

At a glance

Background

As the state's regulator of the marine safety system, the Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director), through Transport Safety Victoria (TSV), needs access to accurate and reliable information on how well the system is working. The Safety Director also needs to know how well other co-regulators and duty holders are adhering to and enforcing safety standards applicable under the Marine Safety Act 2010 (the Act) and Marine Safety Regulations 2012.

Conclusion

TSV cannot demonstrate that current marine operations and safety management systems are effective, as it has no framework for reliably evaluating this, or for assessing whether duty holders, waterway managers and enforcement agencies are effectively discharging their statutory obligations.

Findings

- TSV does not have adequate arrangements in place to systematically monitor and report on the effectiveness of marine operations, statewide safety management systems and the related performance of duty holders.

- This critical gap means that TSV lacks the information it needs to effectively target and prioritise its regulatory activities.

- TSV and waterway managers have longstanding concerns regarding the lack of funding that have yet to be satisfactorily resolved.

- The Act requires revenues from prescribed fees to be used for boating and related safety purposes. However, there is no public reporting on the collection and use of these funds to provide assurance that existing fee revenue is being effectively and efficiently applied across the marine safety system.

Recommendations

- That the Safety Director systematically assesses and regularly reports on the efficiency and effectiveness of Victoria's marine safety system.

- That DTPLI reviews the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for supporting effective implementation of the marine safety regulatory framework.

2.1 Introduction

The objects of the Marine Safety Act 2010 (the Act) are to promote:

- the safety of marine operations

- the effective management of safety risks in marine operations and in the marine operating environment

- continuous improvement in marine safety management

- public confidence in the safety of marine operations

- involvement of relevant stakeholders in marine safety

- a culture of safety among all participants in the marine operating environment.

A key measure of the marine safety system's effectiveness, therefore, is how well it controls the safety of marine operations, management of safety risks and compliance with related safety standards.

The Act, the Marine Safety Regulations 2012 (the Regulations) and gazetted waterway rules specify these standards and how they apply to marine activities, safety infrastructure, duty holders and waterway managers.

As the state's regulator of the marine safety system, the Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director), supported by Transport Safety Victoria (TSV), has a statutory responsibility to effectively coordinate with its co-regulators—waterway managers, Victoria Police, local port managers, port management bodies—to monitor and enforce these standards and assure compliance with the Act and the Regulations.

To discharge these functions effectively, TSV needs access to accurate and reliable information on how well the system is working to achieve the objects of the Act. It also needs to know how well other co-regulators and duty holders are adhering to and enforcing safety standards.

This information is critical to enable TSV to effectively target its regulatory activities and to reliably assess and improve its own performance as a regulator.

This Part of the report examines how effectively TSV monitors the performance of the marine safety system.

2.2 Conclusion

TSV cannot demonstrate that it is effectively and efficiently regulating marine safety, as it has no framework to reliably evaluate this, or to assess whether duty holders, waterway managers and enforcement bodies are effectively discharging their obligations and complying with the Act and the Regulations.

The absence of such arrangements significantly impedes TSV's accountability for performance, including its ability to effectively regulate safety. Consequently, TSV cannot assure Parliament, the Minister for Ports or the community that its current approach to regulating marine safety is working.

These deficiencies, coupled with longstanding funding concerns by TSV and waterway managers means that there is insufficient assurance that state funds are being effectively and efficiently applied across the marine safety system.

2.3 System-wide monitoring arrangements

The Safety Director has a range of statutory responsibilities that create a strong imperative for monitoring the performance of the marine safety system in achieving the objectives of the Act. These include:

- monitoring compliance with marine safety laws

- making appropriate waterway rules

- registering vessels and licensing vessel operators

- developing and enforcing appropriate standards for navigation, maritime safety and related infrastructure

- coordinating and supporting the implementation of the Safety Director's Marine Enforcement Policy by members of the police force, transport safety officers and any persons employed or engaged by port management bodies, local port managers and waterway managers.

The Safety Director has no explicit function under the Act to oversee waterway managers. The then Department of Transport's 2009 review of the former Marine Act 1988 recognised that most of the above functions nevertheless require the Safety Director to exercise a level of oversight.

TSV undertakes a range of activities in these areas. However, its existing monitoring arrangements do not enable the Safety Director to assess whether all these responsibilities are being effectively and efficiently carried out. TSV advised it has recently worked to strengthen accountability provisions for its outsourced registration and licensing services.

While TSV has procedures in place for auditing waterway managers and reporting on marine incidents, there are no defined performance targets or documented arrangements for monitoring, assessing and reporting on the effectiveness of the wider marine safety system.

TSV's monitoring is currently limited to public reporting on such activities as the number of audits undertaken of maritime training providers, proportion of safety incidents investigated, and number of recreational vessels inspected. TSV also reports on the type and location of safety incidents across the state's waterways.

Notwithstanding this, these measures offer little insight into the extent to which duty holders and co‑regulators adequately discharge their statutory responsibilities, or the impact of TSV's system-wide monitoring and enforcement efforts.

This critical gap means that TSV lacks the information needed to effectively target and prioritise its education, stakeholder engagement, compliance monitoring and related enforcement activities.

It is important to note that the new regulatory framework is in the early stages of implementation and therefore its impact on longer-term safety outcomes cannot yet be reliably assessed. However, there is an urgent need for data and shorter-term indicators focusing on the immediate performance of the system and its key participants in managing safety risks and achieving compliance with marine safety laws to enable TSV to focus and prioritise its regulatory activities.

This audit identified that there is a pressing need for TSV to establish such arrangements, as there is little assurance that:

- TSV and all waterway managers adequately assess and manage recreational maritime safety risks in accordance with the Act

- safety education and promotion activities are adequately informed by reliable data on current trends in the safety of marine operations, performance of safety management systems and impact of previous education initiatives

- critical safety controls—including navigation aids, signage and waterway rules—are fit for purpose, adequately address current risks, and comply with the Act

- enforcement activities are sufficient, effectively coordinated amongst co‑regulators and adequately targeted based on reliable information on risks

- current funding arrangements are sufficient to support effective implementation of the regulatory framework

- TSV is effectively prioritising its regulatory activities to optimise the impact and use of its limited resources.

These critical shortcomings, discussed further in Parts 3, 4 and 5 of this report, mean there is currently little evidence to demonstrate that TSV, duty holders and co‑regulators are effectively implementing the regulatory framework and achieving the objectives of the Act.

In October 2013, TSV started work to establish a more comprehensive framework for benchmarking its regulatory performance by measuring the costs and benefits of its regulatory work, along with its efficiency and effectiveness. However, TSV has not yet set a time line by which this is to be achieved.

2.4 Funding arrangements for marine safety management

TSV and waterway managers have longstanding concerns regarding the lack of funding, which have yet to be satisfactorily resolved. This has been consistently raised by them as a critical issue impeding their ability to effectively discharge their legislative responsibilities. TSV has also indicated that, based on its experience, the capacity and willingness of waterway managers to discharge their statutory functions appears directly proportional to their allocated funding, which in most cases is minimal.

2.4.1 Optimising the use of available funding

The funding for recreational maritime safety is derived from state appropriations that can include fees charged for licensing and registration of recreational vessels and operators. The revenue collected from these fees forms part of the state's consolidated revenue administered by the Department of Treasury and Finance and is allocated through the annual Budget process.

Under the Act, including the former Marine Act 1988, all prescribed revenue from these fees must be used by any person, authority or organisation approved by the Minister for Ports for the:

- provision and maintenance of boating facilities and services for the public

- conduct of boating safety, education and promotion programs for the public.

Although under the Regulations only registration revenue is currently prescribed for these purposes, the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) advised that the manner in which it has previously recorded the use of these revenues has encouraged a long-held misconception by DTPLI that licensing revenue must also be used for boating facilities and related safety programs.

Consequently, we found that DTPLI records do not provide sufficient information to reliably acquit the use of registration fee revenues.

Specifically, Figure 2A indicates that $103 million of the $201 million in licensing and registration fee revenue collected from the sector between 2001–02 and 2012–13 was from registration fees, and that total allocations to enforcement activities and from the Boating Safety and Facilities Program (BSFP), administered by DTPLI, during this period amounted to $10.8 million and $56.5 million respectively.

Figure 2A

Fees for boating facilities and safety education, 2001–02 to 2012–13

|

Item |

Total ($ million) |

|---|---|

|

Revenue |

|

|

Boating registration |

102.81 |

|

Licence fees |

98.16 |

|

Expenditure |

|

|

Collection costs |

41.72 |

|

Enforcement |

10.82 |

|

BSFP |

56.50 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data supplied by the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure.

However, DTPLI advised that it cannot confirm the difference between fee revenues collected from and expended in the sector. This is because its records are based on an assumed, notional allocation of these fees to its related programs, given that they are not separately identified in annual appropriations received through the Budget process.

DTPLI advised that the state's expenditure in the marine sector over this period has exceeded fee revenues collected when annual expenditure via the BSFP and its Local Ports Program is considered. DTPLI's Local Ports Program provides annual funding of approximately $11 million to local ports for land and marine infrastructure, and for related shipping and boating activities, but this does not extend to all non-port-related waterways. Additionally, annual allocations from the BSFP between 2005–06 and 2012–13 were approximately $5 million, and will increase by a further $3 million from 2014–15.

While it is evident that this expenditure has occurred, DTPLI acknowledges it cannot formally acquit that all boating registration revenue has been fully expended in accordance with the Act as it does not maintain detailed records of expenditure by port managers.

Proposed funding allocation

A February 2011 briefing from the former Department of Transport to the then Minister for Ports advised of a discrepancy between revenue collected and revenue allocated to the marine sector from the Consolidated Fund.

The then Minister for Ports wrote to the then Treasurer in February 2011 highlighting that the funding challenges faced by local ports had contributed to a significant backlog of required infrastructure works. The minister further advised of his intention to make a submission to the Budget and Expenditure Review Committee seeking its approval for a proposal to allocate all boating registration and licensing fees revenues, net of collection costs, from 2011–12 to the BSFP and Local Ports Program, which both support recreational boating.

DTPLI advised that this proposal was not supported, and thus it did not proceed for consideration by government.

This situation, coupled with the aforementioned deficiencies in statewide monitoring arrangements, means that there is insufficient assurance that existing fee revenue is being effectively and efficiently applied across the marine safety system.

Ongoing concerns about the adequacy of funding to TSV and waterway managers means that urgent action is needed by DTPLI to address this situation and review—in consultation with the Safety Director and central agencies—the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements underpinning the regulatory framework.

2.4.2 Funding to waterway managers

Under the Act, waterway managers are responsible for managing safe vessel movements by establishing and ensuring compliance with boating safety signage, aids to navigation and vessel operating and zoning rules, including temporary rules for mitigating safety risks during water events.

However, TSV has identified that most waterway managers do not consider these tasks form part of their core business as they are not externally funded to undertake them.

Among waterway managers, only port management authorities and local port managers appointed under the Port Management Act 1995 receive funding to carry out these activities in relation to ports under their control. However, it is important to note that this funding does not extend to any inland or other non-port-related waterways they may also be responsible as the designated waterway manager under the Act.

Consequently, most agencies perceive that their appointment by the state as a waterway manager creates a significant and ongoing unfunded liability to establish and maintain expensive safety infrastructure. This is in addition to the unfunded cost of acquitting their statutory obligations to manage safety risks and make sure waterway users comply with the Act and the Regulations.

Starboard mark near Mordialloc Pier marking the entrance to Mordialloc Creek. Note special mark in the background delineating 5 knot zone. Photograph courtesy of Parks Victoria.

Figure 2B illustrates that this is a longstanding issue that has yet to be resolved.

Figure 2B

Limited resources to support waterway management

|

In its July 2009 review of the former Marine Act 1988 the then Department of Transport noted that due to the difficulties and cost inherent in waterway management, and the responsible bodies being ill-equipped to perform it, many managers were carrying out their functions reluctantly. Although it was thought that local community groups would have an interest in managing the use of waterway resources for the benefit of the local community, stakeholder consultations identified that most perceived the cost of performing the role as too high, relative to the benefit. Some options to increase revenue for waterway managers were considered—such as increasing the fees paid by waterway users and directing some or all of it back to waterway managers—but these were not adopted, primarily due to strong opposition from key stakeholders in the boating industry. Instead, the reluctance of some waterway managers was accommodated in the Act by making the role voluntary and limiting their civil liability. However, this has not addressed their fundamental concerns regarding funding. |

Source: Department of Transport discussion paper, July 2009, Improving Marine Safety in Victoria—Review of the Marine Act 1988.

The only funding source for most waterway managers is available through the annual $5 million BSFP administered by DTPLI. The BSFP allocates small grants to eligible agencies, including waterway managers, mainly for the installation of boat ramps and jetties, for which approximately $3.4 million was allocated in 2012–13. This typically leaves only a very small amount for improving navigational aids and boating safety signage, for which approximately $425 000 was allocated in 2012–13.

Access to BSFP funding relies on applicants providing a co-contribution ranging from 20 per cent for boating infrastructure projects to 90 per cent for the installation of aids to navigation.

Boating zone mark off Frankston Pier. Note special mark delineating 5 knot zone Photograph courtesy of Parks Victoria.

TSV and the examined waterway managers advised that this limited pool of funds is therefore not sufficient to adequately support the statutory duties of most waterway managers.

For example, TSV advised the Safety Director in October 2013 that it required a further $104 500 to rectify issues of noncompliance with safety regulations in relation to the 12 waterways under its control, despite reallocating internal funds and receiving funding of $145 000 through the 2013–14 State Budget.

A TSV briefing to the Minister for Ports in October 2013 highlighted that as waterway managers have limited funding, they have limited capacity to fulfil their role and, thus, properly manage related risks. The briefing also highlighted that there are significant issues if a waterway is not actively managed, namely:

- inadequate/deteriorating navigation aids and signage

- inadequate zoning to separate different types of activity

- no understanding of risks

- poor compliance with rules

- increased risks from floating debris or submerged objects

- no oversight of waterway events.

The briefing explained that where there is no appointed waterway manager, TSV may assume the responsibility for managing safety risks. Although this is the case with the vast majority of Victoria's coastline, TSV considers itself to be inadequately resourced to manage this responsibility.

Despite these risks, it is not evident that TSV has been proactive in rigorously analysing the funding gap for waterway managers. In preparing a 2013–14 Budget submission, TSV initially included a funding request for waterway managers which did not make it into the final submission to government. Our review of the draft document found it lacked the robust analysis required of a business case. Specifically, it did not analyse the risks and implications for marine safety arising from identified noncompliant infrastructure, or consider alternative cost-effective options for mitigating these risks.

2.4.3 Funding to Transport Safety Victoria

TSV advised that it receives insufficient funding to properly discharge its regulatory functions. While lack of funds could impede effective implementation of the regulatory framework, shortcomings in TSV's performance monitoring arrangements mean that it cannot presently demonstrate that its existing resources are being effectively applied.

TSV's operating budget for maritime safety in 2013–14 was $13.4 million, comprising:

- $5.2 million to VicRoads for registration and licensing services

- $0.65 million to Victoria Police for enforcement services

- $4.8 million for salaries

- around $2.8 million for fixed costs.

In 2011 TSV also received an additional $790 000 to support its implementation of the Act and a one-off payment of $250 000 to implement related changes to its business processes including upgrading its information technology systems.

However, a July 2012 internal TSV analysis of resourcing issues identified around $4.4 million in unfunded deliverables considered essential for carrying out its regulatory responsibilities. This included an estimated $1.2 million for implementing the Act in 2012–13 and around $740 000 for implementing the national scheme for commercial vessel safety—with the bulk of the remaining shortfall attributed to new and expanded regulatory functions covering compliance monitoring, incident investigations, education activities, waterway rule-making and audits of waterway managers.

However, TSV's estimate of additional funds required was not presented in the context of an analysis of how effectively its current resources are being applied. This means that the basis of its estimated funding shortfall cannot be reliably and transparently assessed.

TSV submitted a revised business case in 2013–14 for additional state funding of $22.8 million over four years to address some of the above issues, however, it was unsuccessful. Specifically, it received only $1.1 million in 2013–14, comprising a $900 000 funding contribution to the Commonwealth Government for administering the national system for commercial vessel safety on state waters, and $200 000 for critical maintenance of navigational aids.

Recommendations

That the Director, Transport Safety:

- develops arrangements to systematically assess and report on the efficiency and effectiveness of Victoria's marine safety system, and related performance of duty holders and co-regulators, and uses this data to target regulatory activities

- reviews management of budgets and financial resources to assure existing funds are effectively and efficiently utilised to optimise regulatory outcomes.

That the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure:

- consults with central agencies and the Director, Transport Safety, to review the adequacy of current resourcing arrangements for supporting effective implementation of the marine safety regulatory framework

- investigates options for the effective and efficient use of all existing revenues from the marine sector to improve marine safety management

- reports publicly on the collection and use of revenue from prescribed fees and all other funds it administers for boating safety and facilities to acquit the requirements of the Marine Safety Act 2010.

3 Identifying and managing recreational maritime safety risks

3 Identifying and managing recreational maritime safety risks

At a glance

Background

The Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director) needs a sound understanding of statewide maritime safety risks in order to effectively prioritise Transport Safety Victoria's (TSV) regulatory activities. Similarly, waterway managers need to accurately understand the nature and severity of prevailing safety risks, the adequacy of associated controls and any consequential impact on their shared responsibility to manage them.

Conclusion

There is little evidence to demonstrate that TSV and waterway managers are effectively identifying and managing recreational maritime safety risks across the majority of the state's waterways.

Findings

- While TSV has a sound approach for assessing risks across the state's managed waterways, its implementation is compromised by critical information gaps and an over-reliance on waterway managers' risk management practices, which are mostly deficient.

- Most of the state's existing waterway rules were established decades ago under the former regulatory arrangements and are not periodically reviewed to assure they remain fit for purpose, effective and support the efficient management of safety risks.

Recommendations

- That waterway managers, in consultation with the Safety Director, establish effective risk management arrangements.

- That the Safety Director strengthens TSV's waterway risk assessments by assuring the quality of information it relies on from waterway managers, estimating the number of unmanaged waterways, cost-effectively assessing risks across the state's unmanaged waterways and systematically reviewing the appropriateness of waterway rules for managing current safety risks.

3.1 Introduction

A key object of the Marine Safety Act 2010 (the Act) is to promote the effective management of safety risks.

The Act establishes that marine safety is the shared responsibility of the Director, Transport Safety (the Safety Director), waterway managers, and all duty holders. Specifically, it provides that the level and nature of their responsibility for marine safety depends on the nature of the risk to marine safety created by their activities or decisions, and their capacity to control, eliminate or mitigate these risks.

As the state's transport safety regulator, the Safety Director through Transport Safety Victoria (TSV) needs to establish a sound understanding of statewide maritime safety risks in order to assess the level and nature of his shared responsibility under the Act to mitigate them, and effectively prioritise his related regulatory activities.

Similarly, waterway managers also need to accurately understand the nature and severity of prevailing safety risks on waters under their control, and any consequential impact on their shared responsibility to manage them.

This Part of the report examines the adequacy of the risk identification and management practices of both the Safety Director and the selected waterway managers.

3.2 Conclusion

There is little evidence to demonstrate that TSV and all waterway managers are effectively managing recreational maritime safety risks.

While TSV has a conceptually sound approach for assessing statewide risks, its implementation is compromised by critical information gaps, an over-reliance on the deficient risk management practices of most waterway managers, and inadequate quality assurance.

Inherent weaknesses in local risk management mean that none of the examined waterway managers could fully demonstrate that all of their waterway users and safety controls comply with the Act and are effective in minimising local safety risks. This includes port management authorities and local port managers whose risk management activities generally do not extend to non-port-related waterways, due in part to limited funding.

Further, while existing waterway rules are a critical component of the state's risk control framework, most were established decades ago under the former regulatory arrangements and are not periodically reviewed to assure their ongoing relevance and appropriateness.

These shortcomings are significant as they mean neither TSV nor most waterway managers can be fully confident about the effectiveness and efficiency of current controls, and the safety of the state's waterways.

3.3 Identifying and assessing waterway safety risks

3.3.1 Transport Safety Victoria's oversight of statewide risks

TSV has developed a conceptually sound waterway risk assessment tool for identifying and assessing risks to safety across the state's managed waterways.

However, critical shortcomings with its implementation mean that TSV cannot be confident it accurately understands the nature or severity of current risks across the state's waterways.

The waterway risk assessment tool considers an appropriate range of relevant data including:

- environmental and physical factors—for example, whether water levels have changed due to wind, irrigation or drought, and whether there are hidden objects in or under the water

- the nature of activities taking place on the waterway—for example, whether high‑speed or multiple activities are likely to occur in the same waterway

- trends in the number and nature of safety incidents and/or related complaints—including requests for assistance with enforcement from the waterway manager