Compliance with the Asset Management Accountability Framework

Overview

Victoria's roads, railways, schools, prisons and hospitals are part of the $265 billion of non-financial assets that government departments and agencies manage. Managing these assets well is important because they support the delivery of services that affect all Victorians. Despite this, many of our audits show that asset management is often neglected or poorly done, with more focus on building or buying new assets than on managing them strategically to get the best value from them.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) released the Asset Management Accountability Framework (the AMAF) in 2016, which aimed to address these issues by increasing agencies’ accountability for how they manage assets and improve their practices. From 2017–18, agencies need to attest to their compliance with the AMAF in their annual reports. In this audit, we examined the reliability of agencies’ attestations of compliance with the AMAF. The audit included all seven departments in place at the time of the 2018 attestation.

We made 11 recommendations. Four were directed to all departments and one to the audit committees of all departments. One was directed to the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and the Department of Justice and Community Safety, and we made five recommendations to DTF.

Transmittal Letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2019

PP No 27, Session 2018–19

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Compliance with the Asset Management Accountability Framework.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

23 May 2019

Acronyms

| AIMS | Asset Information Management System |

| AMAF | Asset Management Accountability Framework |

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| DJPR | Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

| DJR | Department of Justice and Regulation |

| DoT | Department of Transport |

| DPC | Department of Premier and Cabinet |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

Audit overview

Victoria's roads, railways, schools and hospitals form part of $265 billion of non-financial assets that government departments and agencies manage. These assets support the delivery of services that affect all Victorians, so it is important to manage them well. Having up-to-date knowledge of assets and their condition helps government agencies get the best value from their asset-related investments, make good decisions about when to acquire, renew or divest assets, be responsive to changes in demand or use, and provide better services.

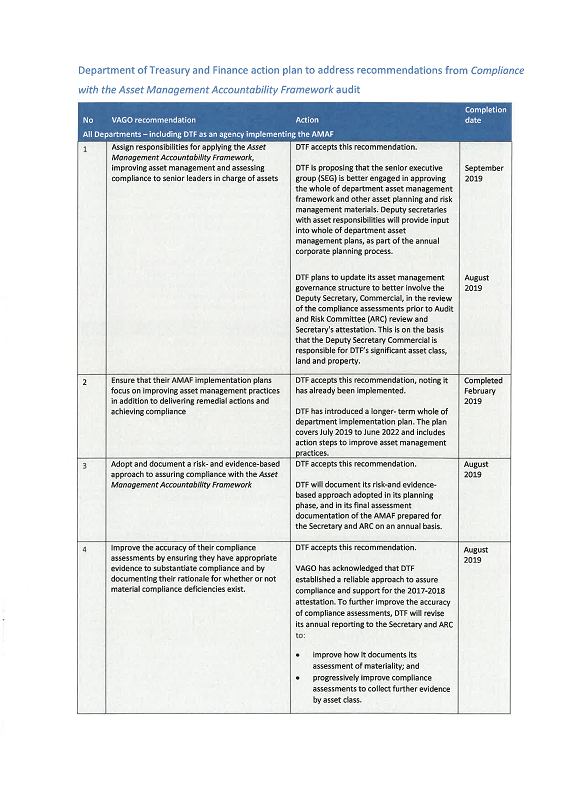

Figure A

Examples of the types and value of Victoria's public assets ($ billion)

Source: VAGO, based on the Treasurer of Victoria's 2017–18 Financial Report.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) released the Asset Management Accountability Framework (AMAF) in 2016 to replace Sustaining Our Assets, introduced in 2000. The AMAF aims to ensure that Victorian public sector agencies manage their assets efficiently and effectively.

|

Attestation—a signed statement in an agency's annual report from the head of the organisation to attest to compliance with the requirements of the standing directions under the Financial Management Act 1994. |

DTF determined that to improve asset management, agencies need to be more accountable, and made this the core focus of the AMAF. The AMAF makes agency heads—such as government department secretaries—or governing boards accountable for applying the framework and its principles, and for complying with its mandatory requirements.

Secretaries must attest to compliance with the AMAF in their annual reports. The departments' audit committees also have important responsibilities to review departmental compliance assessments and attestations. DTF is the policy owner and is responsible for supporting the AMAF and advising government on compliance across the public sector.

The AMAF sets 41 mandatory requirements that agencies must comply with, but allows flexibility in how they do this based on their operating environment and the criticality and complexity of their assets. The requirements span a range of activities including resourcing, governance, risk management, performance monitoring and information management.

|

An asset's criticality refers to its importance to delivering services, measured by the consequences if the asset fails or is otherwise incapable of providing the service. |

The requirement to apply the AMAF is one of the standing directions made under the Financial Management Act 1994. The Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016 (the standing directions) was the version in place at the time of the 2018 attestation. Agencies must attest to compliance with all standing directions and related instructions in their annual report and disclose any significant issues (material compliance deficiencies) that are likely to impact the agency's or the state's reputation, financial position or financial management. An agency only attests publicly whether it has any significant or material deficiencies—it does not need to attest to non-material deficiencies. If an agency has nothing material to disclose, it must attest that it complies with the standing directions.

|

A material compliance deficiency is a compliance deficiency that a reasonable person would consider has a material impact on the agency or the state's reputation, financial position or service delivery. |

Departments made their first public attestation of compliance with the AMAF at 30 June 2018, in their 2017–18 annual reports. This first audit of compliance with the AMAF focused on how the government departments applied and assured compliance with the framework. As leaders among government agencies, we expect departments to be exemplars in applying government policies.

As the AMAF is new, DTF did not expect departments to fully comply with all 41 mandatory requirements by the time of the 2018 attestation. Our discussions with departments at that time identified that they were still implementing the AMAF. Recognising this, we did not audit compliance with each mandatory requirement. Instead, we audited the approaches departments took to apply the AMAF and provide assurance about the levels of compliance they achieved.

This audit's objective was to determine the reliability of departments' attestations of compliance with the AMAF. The audit included all seven departments in place at the time of the attestation:

- Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR), which split on 1 January 2019 into the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR) and the Department of Transport (DoT)

- Department of Education and Training (DET)

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP)

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)

- Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR), now renamed as the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS)

- Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC)

- Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF).

Conclusion

Five departments use reliable approaches to determine the extent to which they comply with the AMAF's mandatory requirements. For the other two departments, their approaches are not detailed enough for them to assess whether they comply given the criticality, complexity and risks of their assets.

DEDJTR and DET demonstrated better practice in how they planned to implement the AMAF and assure compliance. This stems from the active involvement of their senior leaders, who have considered the criticality, risk and complexity of their assets, overseen implementation across the whole of their departments and, most importantly, are motivated to improve asset management as they understand its value to the success of their service delivery.

The remaining departments limited their whole-of-department asset management efforts to addressing compliance gaps ahead of the 2018 attestation. Many find it challenging to understand how best to implement the AMAF and what the right approach looks like. The better practices of DEDJTR and DET provide a good opportunity for them to learn from their peers, and some are already planning further action.

The standing directions guidance allows agencies to focus their compliance efforts on areas they identify as being higher risk, to reduce any unnecessary compliance burden. However, departments and their audit committees cannot readily show how they apply risk-based approaches to their compliance-related activities.

The wording that DTF requires agencies to use in attesting to compliance with the standing directions means that departments' attestations do not accurately reveal how well they are complying with the AMAF. This is because departments must attest that they 'comply' with all aspects of the standing directions collectively, unless they are aware of a 'material deficiency'.

Although DTF has helped the departments to apply the AMAF, there are still inconsistencies in the way departments interpret the AMAF's requirements and their accountability and compliance responsibilities.

AMAF implementation is at an early stage and all departments need to sustain their initial focus and address their asset management improvement needs. This will help departments to make better investment decisions and get more from the assets they need to deliver services over the asset lifecycle.

Findings

Applying the AMAF

AMAF implementation approaches

The benefits of a whole-of-department approach to implementing the AMAF include building a consolidated picture of a department's asset management strengths and weaknesses, which helps prioritise and direct effort and monitor progress across the department.

In the lead up to the 2018 attestation, one department—DEDJTR—approached the AMAF as an opportunity to improve the way it managed its assets. DEDJTR planned holistically for what it needed to improve to meet the AMAF's aims and principles. It also assessed whether it had the asset management capability and culture needed to support improvement. DJPR and DoT each adopted this implementation approach when they formed.

DET already had a plan in place to improve its asset management that pre-dated the AMAF.

Of the remaining departments, DHHS did not have a whole-of-department approach to implementing the AMAF. The other departments' implementation approaches focused on filling key gaps in policies and procedures against the mandatory requirements, rather than planning what they needed to embed these policies and procedures as 'business as usual' asset management practices.

|

An asset class refers to a group of assets that have similar physical and service characteristics. For example, public housing and public prisons are asset classes. |

Half of the AMAF's 41 mandatory requirements relate to leadership. We found that senior leaders—deputy secretaries—in three departments were actively involved in driving the AMAF implementation and in overseeing progress and compliance at a whole-of-department or significant asset class level. For example, they led departmental asset management steering committees or provided specific feedback on key asset management documents. These departments had better implementation and compliance assurance approaches than other departments.

All departments have increased focus on asset management because of the AMAF. Actions have included updating policies and procedures, conducting asset stocktakes, creating new asset management positions and improving asset management capability. Since the 2018 attestation, all but one of the departments with a whole-of-department approach to implementing the AMAF have improved their approaches, for example, by revising their implementation plans, governance arrangements or asset management plans.

|

A whole-of-department asset management plan describes the asset management policy and strategy and outlines the system of policies and procedures that guides asset management across the department. The plan may comprise one document for departments with simple assets or several whole-of-department documents for those with more complex assets. |

Whole-of-department asset management plans

In the lead up to the 2018 attestation, five departments introduced a whole-of-department asset management plan. DET had one before the introduction of the AMAF.

DEDJTR developed its plan to a level that addressed the mandatory requirements relevant to a whole-of-department plan. It included enough information to guide consistent asset management across its asset classes, appropriate to the department's size and the complexity of its asset portfolio.

The strengths of DEDJTR's plan are that it:

- communicates and establishes a shared understanding about the purpose, direction and expectations for asset management across different asset classes

- drives the department to improve capability and change practices in response to identified needs

- highlights the roles of senior leaders in asset management.

DHHS did not have a whole-of-department plan, but developed individual plans for its significant asset classes. It has missed the opportunity to direct and coordinate asset management activities across its different asset classes to achieve its whole-of-department objectives.

|

The AMAF describes an asset management system as a set of interrelated elements that establish an organisation's asset management policies, objectives, and processes to achieve those objectives. |

We identified opportunities for the other departments to improve their plans. Common weaknesses include providing insufficient detail on asset-related risk management and the asset management strategy, or inadequate references to the key policies and procedures that comprise an asset management system.

Checking compliance

Departments' 2018 attestations

All departments attested to compliance with the AMAF in their 2017–18 annual reports as part of their attestation of financial management compliance. Two of the seven departments identified material compliance deficiencies related to the AMAF. Although these attestations alert Parliament and the community to the most significant or material compliance deficiencies, several issues reduce their value:

- The attestations do not give a true indication of the level of compliance with the AMAF, because the standing directions require agencies with no material deficiencies to describe themselves as 'compliant' even if they have non-material deficiencies, as all departments did.

- The standing directions require agencies to assess compliance with the AMAF's mandatory requirements, but do not require agencies to use the assessment to inform the attestation. This risks some agencies overlooking potential material deficiencies.

- Not all agencies that disclosed a material deficiency provided information on the asset class to which the deficiency related or why it was considered material.

Departments' checks on compliance

Departmental arrangements for overseeing compliance are sound, but can improve. Approaches commonly include establishing a steering committee or reference group to oversee the AMAF's implementation and using the corporate finance group to coordinate compliance assessment across a department. In departments with the most reliable assurance approaches, senior leaders are involved in the steering committee and in endorsing compliance assessments. Senior leaders have authority to drive reliable and accurate processes and are directly accountable for progress and outcomes.

The standing directions cover 50 financial management topics and include 458 financial management obligations, of which the AMAF is one. Not all obligations apply to every department. Most departments used their existing arrangements for other financial management requirements to assure compliance with the new AMAF requirements. Internal audits of these arrangements identify that they are sound, but we found room for departments to improve the way they apply their arrangements to assure compliance with the AMAF.

Departments should take a risk-based approach to assure compliance across asset classes and to guide the level of evidence needed to do this. They are not doing this or, if they are, they have not documented and communicated their approaches. Some departments considered risk in deciding whether to assess compliance at a whole-of-department level or individually for significant asset classes, but none transparently took a risk-based approach to determine the levels of evidence or frequency of compliance assessments needed across their asset classes.

Two other issues resulted in some departments overstating their levels of compliance:

- There was inadequate evidence or incorrect identification of whether a requirement does or does not apply. For example, most departments consider they comply with the AMAF's requirements where they have evidence that a necessary process exists, without having evidence of how they applied the process.

- There was insufficient verification—only two departments verified their compliance assessments, and both found inaccuracies.

Departments need to better support their staff to make accurate and consistent assessments—for example, through providing templates, guidance and training as needed.

Audit committees' checks on compliance

Each department's audit committee needs to satisfy itself with the veracity of the department's recommended attestation of compliance with the AMAF before the Secretary approves it for the annual report. The committee also needs to review the department's annual assessment of compliance, and review and monitor the department's actions to address any compliance deficiencies. The standing directions encourage committees to take a risk- and evidence-based approach to their review activities.

The seven audit committees all received reports on the AMAF prior to reviewing the 2018 attestations. Audit committees followed one of two different approaches to review the departmental compliance assessment and satisfy themselves about the attestation:

- three audit committees considered whether they needed to check evidence of compliance to do this—the two that decided they needed to, then did so

- the remaining audit committees relied on departmental advice about compliance, the fact that senior managers in the department had endorsed the attestation, and the positive results from internal audits of their financial management compliance processes.

While DEDJTR's audit committee had documented many elements of its approach, none of the audit committees clearly documented how their strategies for reviewing the AMAF compliance assessment and attestation aligned with their asset-related risks. The committees did not record what they reviewed to satisfy themselves about the level of compliance reached or the compliance attestation.

An audit committee's responsibilities span a broad range of departmental risk and financial management activities, including reviewing compliance with the standing directions. This gives committees every reason to take a risk-based approach, but they need to be transparent about the approach they take.

Four audit committees received no information prior to the attestation about the requirements that were rated 'compliant', such as the compliance rating against each mandatory requirement or a description of the evidence substantiating those rated 'compliant'. Instead, the focus of the information they received was on compliance deficiencies. Three committees did not receive a rationale for why the departments determined their deficiencies were not material.

Supporting implementation and compliance

DTF has fulfilled its responsibilities under the AMAF to support the AMAF's implementation. This includes running regular asset management working group meetings for department representatives and producing the Asset Management Accountability Framework Implementation Guidance (the AMAF implementation guidance) in March 2017. DTF has also provided further guidance on specific issues, such as applying the AMAF to intangible assets and determining the materiality of compliance deficiencies.

This audit and DTF's 2018 review of the AMAF's implementation progress found gaps and inconsistencies in how departments interpret and apply the AMAF requirements and the standing directions. While departments remain accountable for applying the AMAF, DTF can provide more support and clarity on these issues. This includes clarifying:

- the relative importance of improving asset management compared to complying with the mandatory requirements

- the need to assess compliance against all 41 mandatory requirements and whether or when agencies are expected to fully comply with the mandatory requirements

- how departments can apply risk-based approaches to assessing compliance with the AMAF

- how agencies should approach the 2020–21 maturity self-assessments

- how it defines the concepts of attestation, compliance, compliance deficiency and material deficiency in the AMAF and the standing directions

- that the attestation only identifies agencies with any material compliance deficiency and does not identify whether agencies are compliant.

Based on the results of this audit, we consider it would be beneficial for DTF to conduct an evidence-based evaluation of the effectiveness of the AMAF after a further period of implementation. An evaluation would determine whether the AMAF is driving stronger leadership and improved asset management, and whether it is achieving its intended outcomes.

DTF's guidance for the standing directions identifies that DTF will oversee the standing directions from 2016–17. DTF has some arrangements in place to do this. One arrangement involves requesting annual summaries from departments about financial management compliance in the department and its portfolio agencies. Inconsistencies in how departments report against these requests limit the value the summaries provide as an oversight mechanism.

Recommendations

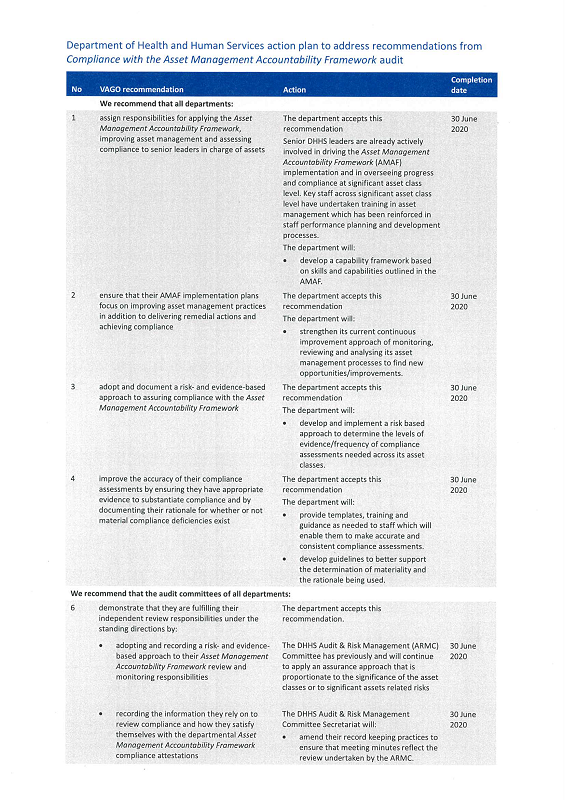

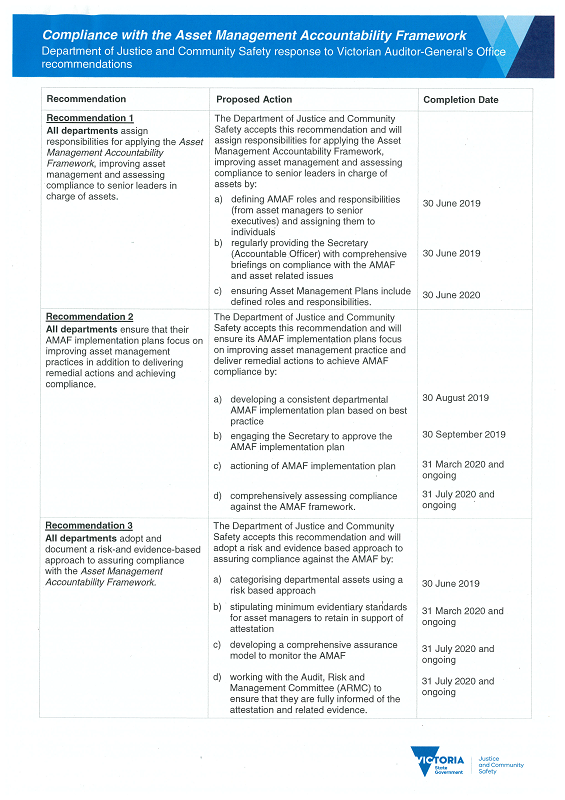

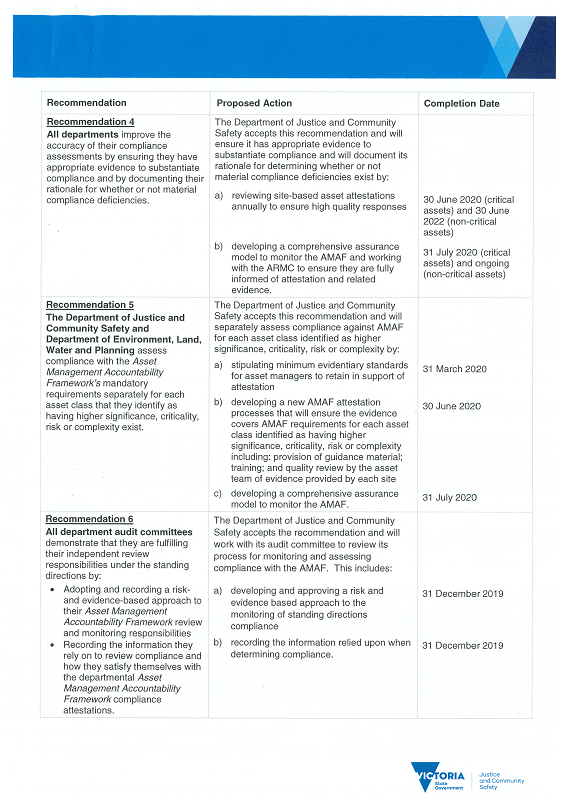

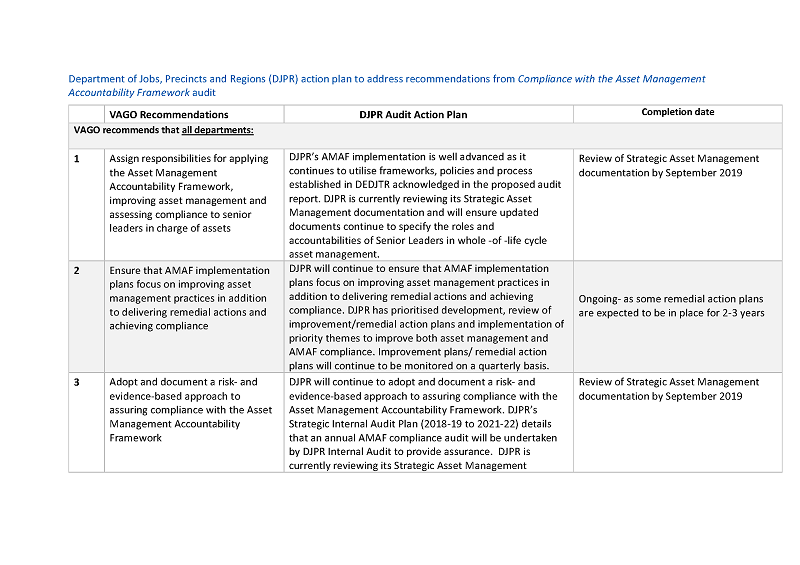

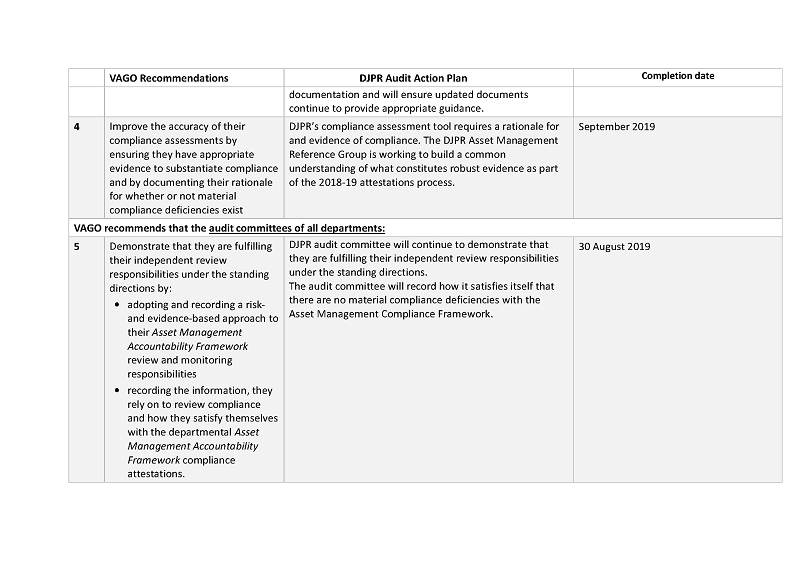

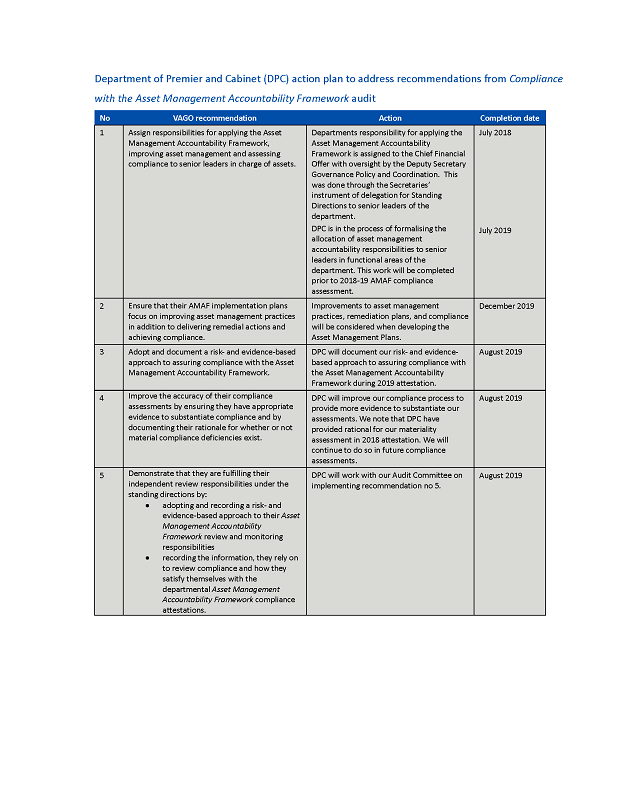

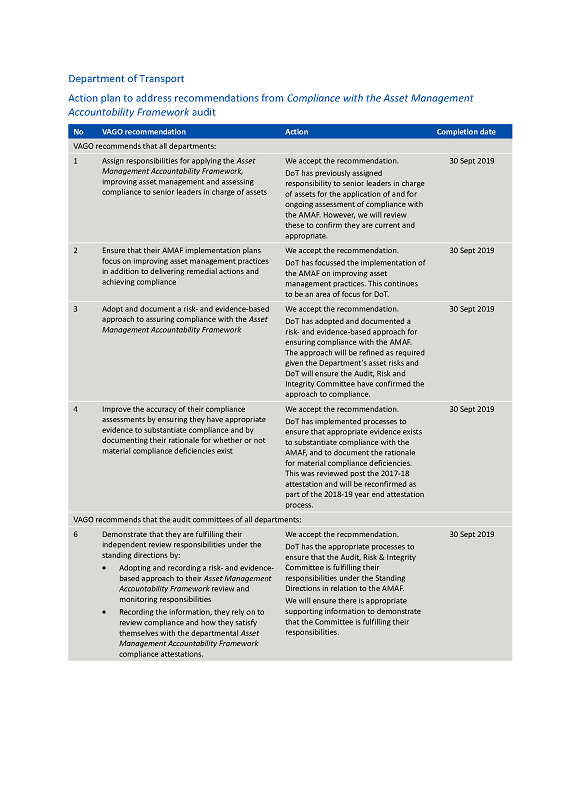

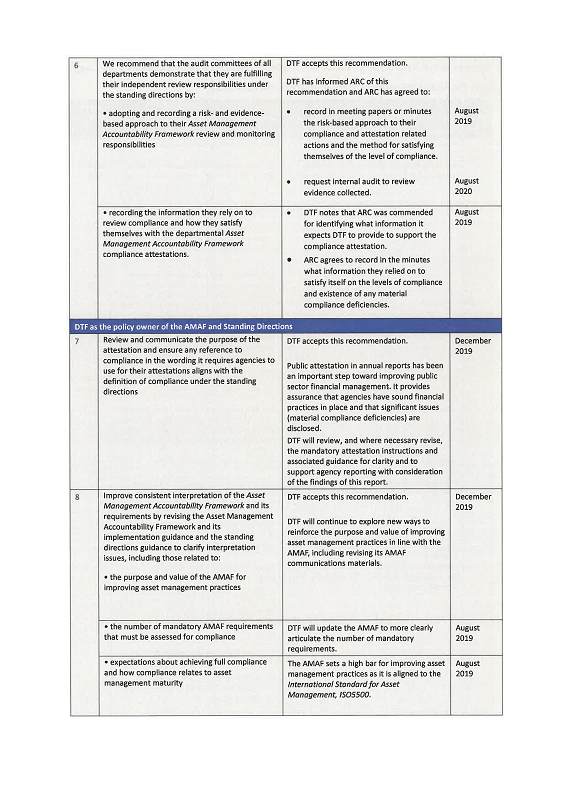

We recommend that all departments:

1. assign responsibilities for applying the Asset Management Accountability Framework, improving asset management and assessing compliance to senior leaders in charge of assets (see Sections 2.4 and 3.3)

2. ensure that their Asset Management Accountability Framework implementation focuses on improving asset management practices in addition to delivering remedial actions and achieving compliance (see Section 2.2)

3. adopt and document a risk- and evidence-based approach to assuring compliance with the Asset Management Accountability Framework (see Section 3.3)

4. improve the accuracy of their compliance assessments by ensuring they have appropriate evidence to substantiate compliance and by documenting their rationale for whether or not material compliance deficiencies exist (see Section 3.3).

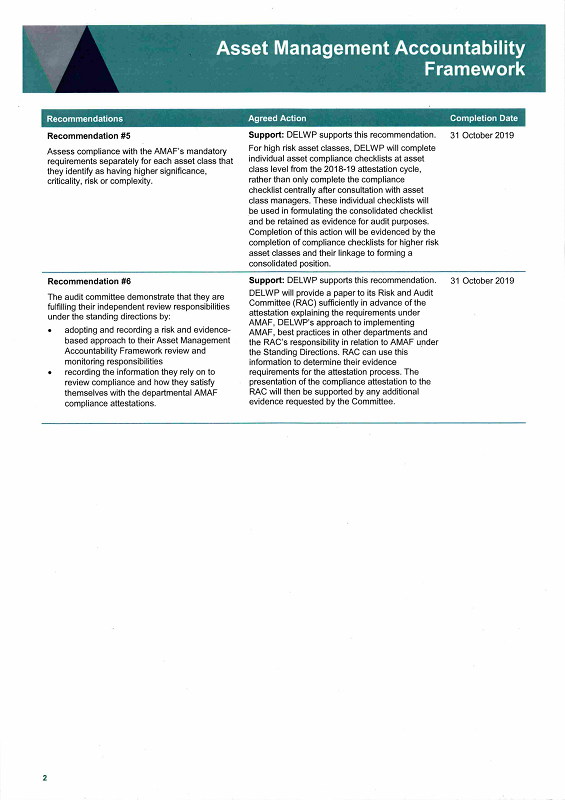

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and the Department of Justice and Community Safety:

5. assess compliance with the Asset Management Accountability Framework's mandatory requirements separately for each asset class that they identify as having higher significance, criticality, risk or complexity (see Section 3.3).

We recommend that the audit committees of all departments:

6. demonstrate that they are fulfilling their independent review responsibilities under the standing directions by:

- adopting and recording a risk- and evidence-based approach to their Asset Management Accountability Framework review and monitoring responsibilities

- recording the information they rely on to review compliance and how they satisfy themselves with the departmental Asset Management Accountability Framework compliance attestations (see Section 3.4).

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance:

7. review and communicate the purpose of the attestation and ensure any reference to compliance in the wording it requires agencies to use for their attestations aligns with the definition of compliance under the standing directions (see Sections 3.2 and 4.2)

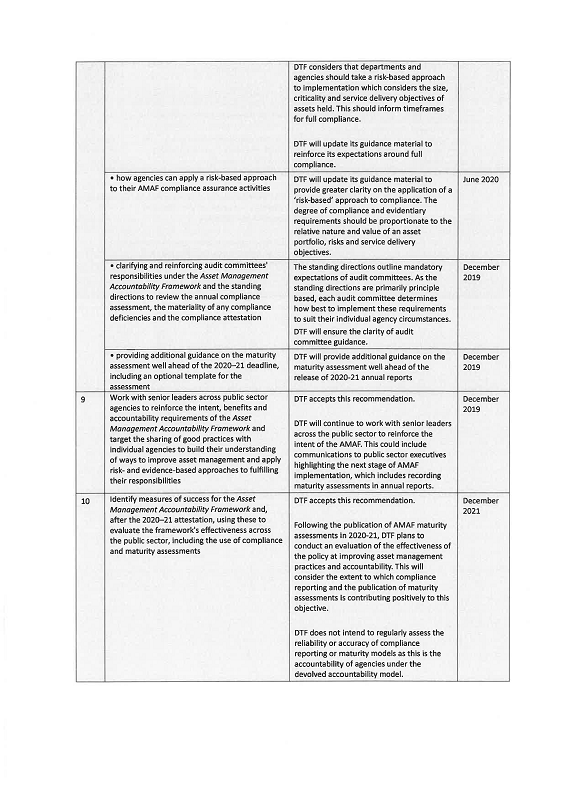

8. support consistent interpretation of the Asset Management Accountability Framework and its requirements by:

- revising the Asset Management Accountability Framework and its implementation guidance and the standing directions guidance to clarify interpretation issues, including those related to:

- the purpose and value of the Asset Management Accountability Framework for improving asset management practices

- the number of mandatory Asset Management Accountability Framework requirements that must be assessed for compliance

- expectations about achieving full compliance with the Asset Management Accountability Framework and how compliance relates to asset management maturity

- how agencies can apply a risk-based approach to their Asset Management Accountability Framework compliance assurance activities

- clarifying and reinforcing audit committees' responsibilities under the Asset Management Accountability Framework and the standing directions to review the annual compliance assessment, the materiality of any compliance deficiencies and the compliance attestation

- providing additional guidance on the maturity assessment well ahead of the 2020–21 deadline, including an optional template for the assessment (see Sections 4.2 and 4.3)

9. work with senior leaders across public sector agencies to reinforce the intent, benefits and accountability requirements of the Asset Management Accountability Framework and target the sharing of good practices with individual agencies to build their understanding of ways to improve asset management and apply risk- and evidence-based approaches to fulfilling their responsibilities (see Sections 2.2, 2.4 and 3.3)

10. identify measures of success for the Asset Management Accountability Framework and, after the 2020–21 attestation, using these to evaluate the framework's effectiveness across the public sector, including the use of compliance and maturity assessments (see Section 4.2)

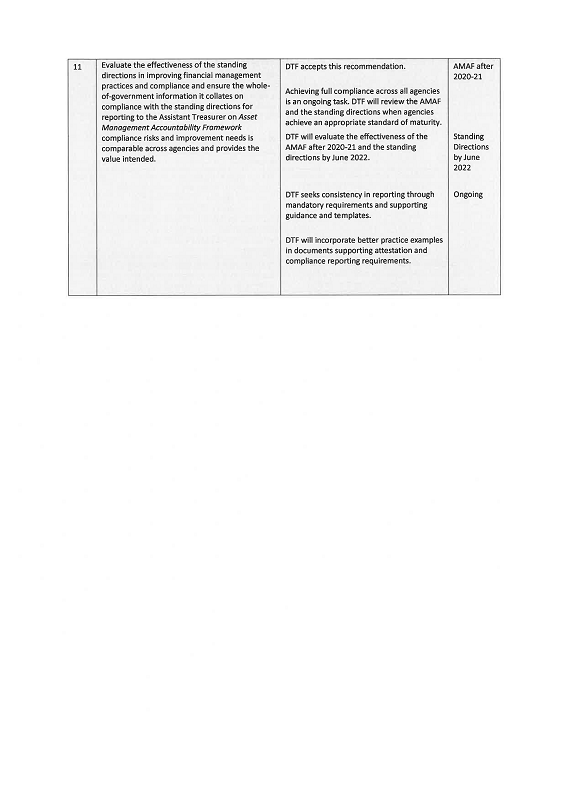

11. evaluate the effectiveness of the standing directions in improving financial management practices and compliance, and ensure the whole-of-government information it collates on compliance with the standing directions for reporting to the Assistant Treasurer on Asset Management Accountability Framework compliance risks and improvement needs is comparable across agencies and provides the value intended (see Section 4.3).

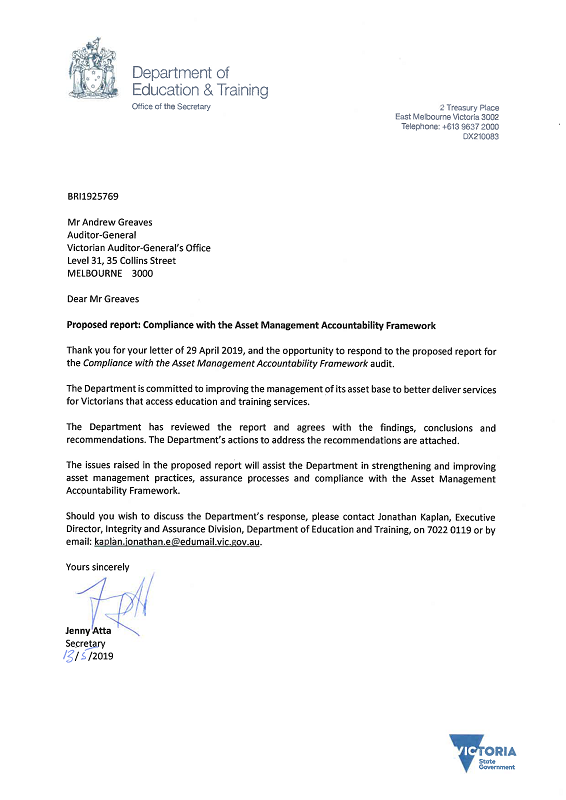

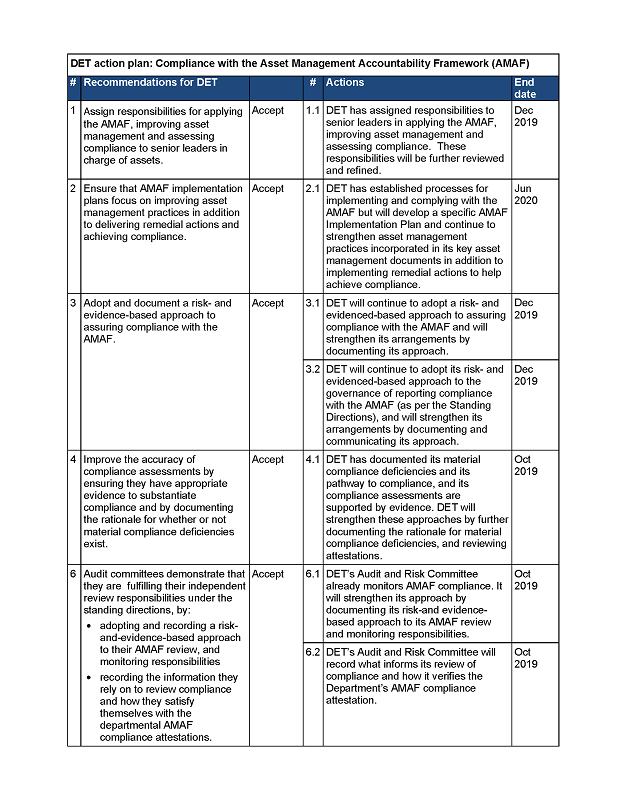

Responses to recommendations

We consulted with all departments and considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to them and asked for their submissions or comments.

All departments have accepted the recommendations from this audit and have planned actions to address them. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

1 Audit context

1.1 Background

Many public services rely on public assets such as trains, roads and schools to support their delivery. The Treasurer's 2017–18 Financial Report identifies that the State of Victoria controlled a total of $265 billion of non-financial assets at 30 June 2018. Inadequate management of these assets can affect the services these assets provide or support, and, therefore, the quality of life for all Victorians.

Our Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2015–16 to Parliament noted that although the state is spending more on adding new assets than it is on replacing existing assets, this ratio is trending downward, and it is spending less than it has in the past. Our report emphasised that reliable asset knowledge is fundamental to making strategic decisions about infrastructure spending.

Asset management involves a range of related activities throughout the asset lifecycle from the initial assessment of investment proposals, ongoing maintenance and renewal through to asset replacement or disposal decisions.

Good asset management allows the government to keep track of the number, location, performance and condition of its assets and enables it to:

- get the best value from asset-related investments by directing available funding to identified needs and risks—risks include the potential for services to be disrupted

- bring whole of lifecycle considerations to asset investment, divestment and replacement decisions

- minimise the demand for new assets

- optimise the use and lifespan of existing assets

- allocate maintenance funds effectively

- respond promptly to foreseen and unforeseen changes in demand or use.

1.2 The Asset Management Accountability Framework

Asset management is about knowing the assets held and the purpose they serve, understanding the risks associated with them, having a long-term strategy to manage the assets and risks, and knowing how to deliver the strategy. It is a longstanding management discipline.

DTF released the Victorian Government's AMAF in February 2016. It replaced Sustaining Our Assets, Victoria's previous asset management policy and framework, released in 2000. Despite these asset management frameworks, our audits and other reviews have repeatedly found poor asset management practices in many agencies. When DTF reviewed the past framework's effectiveness in 2013, it determined that a reason for this lack of effectiveness was that agencies were not taking accountability for their performance in managing their assets.

The AMAF aims to address this by strengthening the focus on leadership and accountability for asset management. Its purpose is to help public sector agencies manage their assets efficiently and effectively, provide better services and link asset information to investment decisions.

The AMAF applies to all non-current assets (physical and intangible), excluding financial assets, that government departments, agencies, corporations, authorities and other public bodies control. The AMAF sets 41 mandatory requirements. DTF provides guidance to help agencies implement the framework.

The AMAF makes agency heads or governing boards accountable for applying the AMAF and improving asset management. They must also publicly attest to compliance with the standing directions in their annual reports.

Victoria is the only Australian jurisdiction that applies this combination of accountability, mandatory requirements and public attestation to asset management.

Important characteristics of the AMAF

|

The accountable officer is the agency head:

The responsible body is:

The responsible body attests to compliance with the AMAF. In departments, the Secretary is the accountable officer and the responsible body and has overall responsibility for their agency's financial management, performance and sustainability. |

The AMAF assigns accountability to three key roles in an agency:

- accountable officers—the agency head is responsible for applying the AMAF

- responsible bodies—the board or Secretary is responsible for publicly attesting to compliance with the AMAF

- audit committees—the audit committee is responsible for making sure it is satisfied with the veracity of the agency's compliance assessment and of its proposed attestation of compliance with the standing directions, before the responsible body signs it.

The AMAF aims to help public sector agencies manage their assets efficiently and effectively over the entire asset lifecycle and to:

- provide better and more efficient services

- optimise the longevity of assets

- maximise value for money

- minimise the demand for new assets

- use asset information to better inform investment decisions.

The AMAF identifies six principles to achieve these aims, as seen in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

The AMAF's principles for asset management

Source: AMAF, DTF, 2016.

The AMAF uses the asset definitions under the Australian Accounting Standards and applies to all assets above the threshold value that each agency establishes. It closely aligns with the ISO 55000 series of asset management standards.

How the AMAF works

The AMAF and the standing directions require an agency head—the accountable officer—to ensure the agency applies the AMAF.

The AMAF is designed to allow agencies to apply the framework and meet the requirements in a way that is 'fit for purpose' to suit service delivery objectives and organisational characteristics, such as the agency's size and the complexity of its assets.

DTF has provided guidance on implementation, materiality assessment and intangible assets to help agencies apply the AMAF.

To ensure agencies implement effective asset management systems that meet AMAF aims and principles for good asset management, the AMAF identifies:

- 41 mandatory requirements—what accountable officers must do

- 42 general guidance points—what accountable officers should do.

Appendix B shows the 41 mandatory requirements.

The requirements and guidance are grouped across five themes that span the asset lifecycle—leadership and accountability, planning, acquisition, operation and disposal—and relate to:

- resourcing and skills

- governance and allocating asset management responsibility

- asset management strategy

- risk management and contingency planning

- monitoring the performance of assets and the agency's asset management system

- acquisition, maintenance and disposal

- information management and record-keeping.

The AMAF applies to asset management activities that the agency devolves or outsources, as well as those it manages in-house. It calls for agencies to do two things:

1. Manage their assets well and achieve better practice over time:

- The AMAF requires agencies to self-assess the maturity of their asset management systems and practices periodically from 2020–21.

- It expects that agencies' asset management maturity will increase over time as they continue to apply the requirements and the general guidance.

2. Comply with the 41 mandatory requirements:

- The AMAF requires agencies to attest to their compliance with the 41 mandatory requirements.

- Compliance is enforced through the standing directions.

Figure 1B illustrates the relationship between the improvement and compliance aspects.

Figure 1B

Relationship between the AMAF, improving asset management and compliance

Source: VAGO.

The AMAF does not set a time by which agencies need to achieve full compliance or an appropriate level of asset management maturity.

1.3 Enforcing the AMAF

To enforce accountability and compliance with the mandatory requirements, DTF made applying the AMAF one of the standing directions. This means that the accountable officer must assess compliance with the AMAF annually and publicly attest to compliance in their annual report.

Figure 1C shows how the AMAF relates to the Financial Management Act 1994 and the standing directions and other government policies.

Figure 1C

The relationship between the AMAF and other government policies

Source: AMAF, DTF, 2016.

Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016

The 2016 standing directions replaced the 2003 directions. The changes included the requirement for a public attestation of compliance with all standing directions, replacing the previous system of a public attestation for risk and insurance only and an internal attestation to DTF on the remaining requirements.

To accompany the standing directions, DTF published:

- Instructions supporting the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016 (the standing directions instructions)—more detailed mandatory requirements related to specific directions

- Guidance supporting the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016 (the standing directions guidance)—non-mandatory information to help agencies interpret and implement the directions and instructions.

From November 2018, the Assistant Treasurer became responsible for the standing directions. In December 2018, the Assistant Treasurer revised the standing directions to incorporate ministerial and machinery of government changes following the state election. DTF updated the standing directions instructions at this time. We conducted this audit against the 2016 standing directions and instructions because these applied at the time of the 2018 attestation.

The standing directions and instructions include 458 financial management obligations—not all are relevant to every agency—across 50 areas of financial management. The direction related to the AMAF is one of the 458 obligations.

Compliance requirements

The standing directions require agencies to assess and report compliance with all directions on financial management, including the AMAF. The standing directions require an agency to:

- assess compliance annually

- identify, respond to and report on material compliance deficiencies

- attest to compliance in its annual report

- use its internal audit function to review compliance with all requirements of the standing directions and instructions over the agency's three- or four-year internal audit planning cycle.

The standing directions also set responsibilities for the agency's audit committee, including reviewing the agency's annual compliance assessment and monitoring remedial actions to address all compliance deficiencies. The standing directions require departments to provide a compliance summary report to DTF.

Under the AMAF, agencies are accountable for compliance. The AMAF does not give DTF responsibility for checking or verifying agencies' compliance—this is up to accountable officers and audit committees. The compliance assessments and reporting rely on agency self-assessments.

Attestation requirements

Agencies' obligations to attest to compliance with the AMAF come from two sources—the standing directions and the AMAF.

Standing direction 5.1.4 requires:

- a department's Secretary to attest in the department's annual report to compliance with applicable requirements in the Financial Management Act 1994, the standing directions and instructions, and to disclose all material compliance deficiencies

- the department's audit committee to review the attestation.

The AMAF mandatory requirement 3.1.3 requires:

- a department's audit committee to be satisfied with the department's proposed attestation of compliance with the AMAF prior to finalising the attestation in the annual report—to be confident about its veracity

- agencies to follow other standing directions related to ensuring compliance and supporting the attestation.

The AMAF implementation guidance explains that the attestation's purpose is for accountable officers to demonstrate their oversight of asset management. When an attestation does not identify a material compliance deficiency, the agency is deemed 'compliant' with the AMAF and the standing directions.

Transition arrangements for attestation and maturity

The AMAF supported a two-year transition period leading up to formal attestation in agencies' 2017–18 annual reports to give agencies time to implement any new policies and systems. During this period, DTF expected agencies to implement the AMAF and conduct a trial attestation in 2016–17.

For the 2017–18 financial year, agencies were required to assess their compliance with the AMAF and, in their annual reports, attest to compliance on 30 June 2018 and disclose any material compliance deficiencies.

From the 2018–19 financial year, and on an ongoing basis, agencies' assessments and attestations will apply to a compliance assessment for the entire financial year.

From 2020–21, each agency must self-assess its level of asset management maturity at least every three years and state this in its annual reports. This requirement is designed for agencies to demonstrate progress towards better practice asset management.

1.4 DTF's responsibilities under the AMAF and the standing directions

Under the Victorian Government's devolved accountability model, responsible bodies must manage their assets in a manner that is consistent with their specific circumstances and the nature of their assets, and are accountable for their compliance. DTF has roles in supporting implementation of the AMAF and the standing directions. However, it does not have responsibility for checking or verifying agencies' compliance.

DTF's responsibilities for the AMAF

Under the AMAF, DTF is responsible for ensuring the framework remains up to date and consistent with legislation and other associated government asset policies and frameworks. DTF must also advise the government on whole-of-government asset management issues, which helps the government make decisions on asset planning, acquisition, and operational and disposal matters.

DTF's responsibilities for the standing directions

Under the standing directions, DTF may issue mandatory instructions that are linked to specific standing directions to provide more detail about the mandatory requirements. DTF may also issue non-mandatory guidance to provide supporting information in relation to the interpretation and implementation of the standing directions and instructions.

1.5 Departmental responsibilities for applying the AMAF

Government departments are one type of agency that the AMAF applies to. Each department is responsible for applying the AMAF to the assets it owns or has responsibility to manage, and for attesting to compliance with the AMAF for these assets.

Under the Public Administration Act 2004, each department also has oversight and support responsibilities for related public entities—portfolio agencies—that share the same minister(s) as the department. The standing directions require departments to oversee the financial management of their portfolio agencies, including their asset management.

Secretaries

Departmental secretaries are the accountable officers. They are responsible for applying the AMAF, meeting the requirements to manage assets under their control and attesting to all applicable standing directions.

Audit committees

Each department has an audit committee, which plays a key role in providing departmental management with independent and objective advice on matters including financial reporting, risk management, and internal and external audits.

The AMAF requires audit committees to satisfy themselves with the veracity of the department's recommended attestation of compliance with the AMAF and its disclosure of any material compliance deficiencies.

The standing directions and related instructions and guidance further require committees to:

- review the department's annual assessment of compliance with the AMAF

- provide the Secretary with assurance, advice and recommendations on the level of compliance attained, issues to be resolved and proposed mitigation plans

- review and monitor the actions the department takes to remedy compliance deficiencies.

1.6 Departmental asset responsibilities

The departments are responsible for a significant proportion of the Victorian Government's assets. The value and types of assets vary significantly between departments, as highlighted in Figure 1D and the following sections.

Figure 1D

The value of non-financial assets controlled by government departments at 30 June 2018

Source: VAGO, based on departments' 2017–18 annual reports.

Machinery of government change

Machinery of government refers to the allocation of functions and responsibilities between departments and ministers. From 1 January 2019:

- DEDJTR separated into two new departments—DoT and DJPR

- DJR changed to DJCS.

DEDJTR and DJR were the departments in place at the time of the 2018 attestation, so they were the focus of our audit analysis and are the departments we mostly refer to in this report.

Department of Treasury and Finance

DTF held $878 million of non-financial assets at 30 June 2018, with $825 million of this in land and buildings. Some DTF portfolio agencies, including CenITex and the Old Treasury Building Committee of Management, also manage assets.

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources

DEDJTR was responsible for driving Victoria's economic development and job creation. Its major portfolio agencies included Public Transport Victoria, V/Line, VicRoads and VicTrack.

At 30 June 2018, DEDJTR directly managed $2.8 billion of non-financial assets, including $708 million related to agriculture, $430 million related to creative industries, $232 million related to tourism, major events and international education, and $172 million related to major projects. More than $92 billion of transport assets sit with two portfolio agencies, VicTrack and VicRoads.

Department of Education and Training

DET provides learning and development support and services for schools, TAFEs and early childhood centres. School property, plant and equipment represent 88 per cent ($24.5 billion) of the department's total assets. Corporate assets, including information technology and intangibles, make up the rest of DET's non-financial assets.

School asset planning and management is the shared responsibility of departmental staff, school principals and school councils. DET is responsible for delivering school infrastructure, funding school assets, and setting asset management policies and standards. Principals are responsible for asset management in schools. The responsibilities of school councils include community engagement, fundraising and the purchasing, use and maintenance of facilities.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

DELWP is responsible for Victoria's planning, local government, environment, energy, forests, emergency management, climate change and water functions.

At 30 June 2018, of DELWP's $9.96 billion non-financial assets, various categories of public land made up $8.3 billion. The remaining $1.6 billion includes 40 000 kilometres of roads, bridges and tracks, office buildings, depots, firefighting equipment and water bores. Major portfolio agencies include the Environment Protection Authority Victoria and water and catchment management authorities.

Department of Health and Human Services

The responsibilities of DHHS encompass areas such as public housing, hospitals, disability, mental health and child protection services. DHHS held $30.4 billion of non-financial assets at 30 June 2018. This figure excludes assets controlled by health and human services agencies that are separate to the department, such as public hospitals.

Department of Justice and Regulation

DJR led the delivery of justice services in Victoria, with service delivery responsibilities ranging from managing the state's adult prisons and youth detention centres to providing consumer protection. At 30 June 2018, DJR held $3.4 billion of non-financial assets, with most of its assets in public prisons.

Department of Premier and Cabinet

DPC supports the Premier, Deputy Premier, the Special Minister of State and other ministers, as well as the Cabinet. DPC reported $660 million of non-financial assets at 30 June 2018. Its major assets are the land and buildings associated with Government House, and public records and facilities in the Public Record Office Victoria.

1.7 Previous audits

Recent reports that have included an asset focus include:

- Protecting Victoria's Coastal Assets, 2018

- Results of 2017–18 Audits: Local Government, 2018

- Results of 2017 Audits: Technical and Further Education Institutes, 2018

- Managing School Infrastructure, 2017

- Managing Victoria's Public Housing, 2017

- Results of 2016–17 Audits: Public Hospitals, 2017

- Results of 2016–17 Audits: Water Entities, 2017

- Managing the Performance of Rail Franchisees, 2016.

A common theme of these audits is that asset management is a critical issue for departments and agencies, as it is important that assets are managed well to deliver good services.

1.8 Why this audit is important

Good asset management is critical to supporting service delivery and achieving value for money from investments in infrastructure and other assets. Previous reviews have identified fundamental weaknesses in the way public sector agencies manage assets across a range of portfolios, from schools and hospitals to transport and coastal protection. Our past audits identified recurring weaknesses in the way public sector agencies manage assets across a range of portfolios. Agencies often focus on building or buying new assets, rather than on managing existing assets strategically to maximise value, and public sector asset management is often neglected or poorly done.

The AMAF aims to remedy this by increasing agencies' accountability for asset management and requiring them to adopt better practice asset management approaches.

This audit assesses aspects of the AMAF's operation early in its rollout. It provides Parliament with assurance about the reliability of the compliance attestations made by all departments and shares good practices from their progress in implementing the AMAF.

1.9 What this audit examined and how

Our audit objective was to determine the reliability of departments' attestations of compliance with the AMAF.

We examined whether departments:

- have sound approaches to implementing the AMAF and supporting an accurate attestation

- have applied their assurance approaches as planned and make reliable attestations.

We focused on the approaches departments had in place to inform their 2018 attestations.

We chose to focus on departments because of the significant value and criticality to service delivery of the assets they manage directly or oversee through their portfolio agencies. We did not examine departments' asset management practices and operations, nor their oversight arrangements for portfolio agencies.

The departments we audited were DEDJTR, DET, DELWP, DHHS, DJR, DPC and DTF.

We also examined DTF's role as the policy owner of both the AMAF and the standing directions.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $595 000.

1.10 Report structure

The structure of this report is as follows:

- Part 2 examines how departments have applied the AMAF through their whole-of-department implementation planning and asset management plans.

- Part 3 focuses on the approaches that departments and audit committees used to assure compliance with the AMAF and support the 2018 attestation.

- Part 4 assesses DTF's actions to support the AMAF's implementation and departments' compliance with it.

2 Applying the AMAF

Previous audits have identified that many departments and agencies need to improve their asset management practices. The AMAF has a strong focus on continuously improving asset management. Departments need well-planned approaches to use the AMAF to improve their practices, and departmental staff need to be well organised and clear about their roles.

We examined how departments planned their AMAF implementation approaches at a whole-of-department level, and the leadership that steered the implementation. We also reviewed the key documents that form whole-of-department asset management plans.

Figure 2A highlights how the AMAF implementation and the whole‑of‑department asset management plan form part of a department's asset management approach.

2.1 Conclusion

The introduction of the AMAF has increased departments' focus on asset management. DEDJTR and DET recognised early that to apply the AMAF they needed to change their practices and document their processes, and they planned how they would do this. These departments positioned themselves to not only achieve compliance, but to improve asset management practice across their organisations. Their senior leaders played a significant role in driving and overseeing this improvement.

The other departments' whole-of-department implementation planning focused on what they needed to do to prepare for the 2018 attestation rather than on their longer-term improvement needs. Three departments are now planning further action to address their longer-term asset needs.

At the time of the 2018 attestation, only DEDJTR had a whole-of-department asset management plan that was comprehensive enough, relative to the complexity of its assets, to coordinate and control its asset-related activities. This is not surprising because, for most departments, having a whole-of-department plan is a new approach to managing their assets. Three departments are now improving or planning to improve their whole-of-department plans.

Departments without a whole-of-department asset management plan or with limited content in their plans may find it challenging to consistently achieve their asset management and service delivery objectives and comply with the AMAF across all their asset-related activities.

Figure 2A

Relationship of AMAF implementation and the whole-of-department asset management plan to a department's overall asset management approach

Source: VAGO.

2.2 AMAF implementation approaches

All departments have a whole-of-department approach to implementing the AMAF except for DHHS, which adopts a 'bottom-up' approach—implementing the AMAF separately for each of its asset classes.

DHHS advised us that it did not embark on a whole-of-department approach because of the variation in responsibilities between asset classes and in the way business areas manage their asset classes.

We consider that a whole-of-department approach would better enable DHHS to:

- understand where its asset management strengths and weaknesses lie

- prioritise, direct and coordinate effort across the department

- monitor progress, not just in implementing the AMAF but in improving asset management.

We reviewed the DHHS public housing group's implementation of the AMAF as an example of its approach for an individual asset class and found that overall it has a good implementation plan. However, gaps remain at the departmental level.

DHHS's June 2018 report to its audit committee highlighted that one asset class was likely to be non-compliant because it had been slow to address deficiencies identified through the department's 2016–17 trial assessment. This demonstrates that the lack of a whole-of-department implementation approach and monitoring can put the department at risk of overlooking certain asset areas, which can negatively impact the implementation process.

Gap analysis

The AMAF implementation guidance suggests undertaking a gap analysis as a starting point for organisations to implement the AMAF. It points out that by evaluating current systems, processes, policies, information and reports, agencies can understand the gaps to achieve compliance with the AMAF and identify any actions required to address these gaps.

We assessed whether departments followed common steps in a gap analysis. Steps include analysing the current state of asset management, identifying the ideal future state—for departments this involves consistently applying the AMAF principles, improving outcomes for assets and service delivery, and achieving compliance—and identifying actions to bridge any gaps.

Four departments completed whole-of-department gap analyses and the remaining three did this for individual asset classes. These exercises helped departments define their asset types and values, assess gaps against each of the AMAF's 41 mandatory requirements, and identify deficient areas and actions to address them.

All but one department considered their capability and practices as part of this gap analysis, along with assessing whether they had the right policies and procedures.

Only DEDJTR comprehensively assessed what it needed to improve to meet the AMAF's aims and principles, and how much it needed to strengthen its asset management culture, capability and practices to be able to do this.

Implementation planning

Implementation planning approaches varied between departments in terms of timing, comprehensiveness, complexity and quality. This did not always align with the complexity of their asset portfolios.

Aligning implementation with asset complexity

The AMAF implementation guidance recommends agencies determine the complexity of their asset portfolios as the basis for scaling their compliance approaches to match need. Together with the gap analysis, this helps departments identify the time, effort and detail of planning needed to implement the AMAF across their assets.

Departments with low complexity may need a simpler plan and shorter time for implementation, while departments with higher complexity and risk will require more effort and a relatively longer time to implement the AMAF.

Figure 2B identifies some of the factors that determine the level of complexity and shows departments' relative positions in terms of asset complexity.

Figure 2B

The relative complexity of the departments' asset portfolios

Source: VAGO.

Figure 2C shows when departments started their implementation planning and DTF's progressive support throughout the journey.

Three departments recognised that implementing the AMAF and applying it across their large organisations and portfolios with multiple asset classes would take a long time—between two and five years.

Figure 2C

Time line of departments' AMAF implementation planning and DTF's support for implementation

Source: VAGO, based on departments' information.

Detail of implementation planning

The departments' implementation plans range from a one-page schematic to more detailed plans. Only three departments—DEDJTR, DET and DTF—have plans that align to the nature of their assets and the breadth of their organisational involvement in asset management. DJPR and DoT each adopted DEDJTR's implementation approach when they formed.

DEDJTR and DET had many good practice elements in their implementation planning approaches, as shown in Figure 2D. Better practices are more common in departments with dedicated resources and trained staff members supporting AMAF implementation. They designed appropriate actions and developed internal guidance to help staff to implement the AMAF.

Figure 2D

Good practices in implementation planning

|

Source: VAGO, based on DEDJTR's and DET's implementation approaches.

The other five departments had short-term implementation approaches that focused on compliance and what they needed to do for the 2018 attestation only. They planned to fill key gaps in policies and procedures against the mandatory requirements, but did not plan beyond that to implement these policies and procedures and meet future needs.

They adopted this short-term implementation approach even though the AMAF does not focus on a time frame for achieving compliance. It recognises that agencies will have different starting points and different pathways towards achieving compliance.

In three departments, the corporate finance and compliance group was the main unit responsible for driving or coordinating the AMAF implementation. This may be appropriate where the asset base is simple and has lower risk. However, where assets are more complex and higher risk, the finance and compliance group found it difficult to drive the whole-of-department AMAF implementation if it did not have strong support from those with asset management responsibilities or expertise.

Departments' implementation progress

Up until the 2018 attestation, departments had introduced a range of actions as part of their AMAF implementation, including:

- developing or updating asset management policies and procedures

- communicating the aim of the AMAF to staff

- conducting stocktakes of certain asset classes

- establishing clearer roles and responsibilities with other asset managers in the department and/or other agencies with roles in the asset lifecycle

- introducing new roles specific to managing assets at a whole-of-department or asset class level and improving asset management capability.

Three departments are now introducing longer-term whole-of-department implementation plans, and three are clarifying and strengthening their governance arrangements. One department does not yet have further implementation activities underway.

Maturity assessment

Although the AMAF does not require a maturity self-assessment until 2020–21, five departments—DEDJTR, DHHS, DPC, DELWP and DJR—conducted one before the 2018 attestation.

DEDJTR built the maturity assessment analysis into its compliance assessment and attestation tool. Each business unit completed multiple compliance and maturity assessments prior to the 2018 attestation. This approach provided an early opportunity for the department to raise staff understanding of asset management maturity and the AMAF implementation journey. It also provided the Secretary with evidence of commitment to and progress in improving asset management.

2.3 Whole-of-department asset management plans

The AMAF aims to support agencies to implement effective asset management systems and be accountable for their assets and asset management. Many of the AMAF's requirements collectively describe an asset management system, and a structured approach for developing, coordinating and controlling asset-related activities.

Our audit included a focus on the key whole-of-department documents departments use to describe their asset management systems, because these documents are important for guiding consistent asset management across the multiple asset classes of each department. We refer to these documents collectively as the 'whole-of-department asset management plan'—not an asset management system—because there are other components of their overall systems.

The whole-of-department asset management plan sets expectations and explains to staff with asset management responsibilities:

- how their asset management should align with corporate service delivery objectives and business systems

- what their asset-related decisions need to consider

- how risk should inform their practices

- the asset information that the department requires from them

- expectations for continuous improvement.

All departments also have a suite of additional policies and procedures that are designed to support asset management, but sit outside the whole-of-department asset management plan. These were not part of this assessment because:

- some are specific to individual aspects of asset management, such as asset disposal policies, maintenance plans and operating procedures

- others are part of the corporate business environment, such as the delegations instrument, occupational health and safety policy, and the procurement manual.

Departments with complex asset portfolios or assets with high-risk exposures may need more detailed information in their whole-of-department asset management plans than those with simple assets or lower risk exposures. The management approaches that different asset managers take should align with the whole-of-department plan, but will necessarily vary between different asset classes and at various stages of the asset lifecycle.

We assessed the comprehensiveness of the whole-of-department asset management plans at the time of the 2018 attestation to determine whether they had enough information relative to the complexity of the departments' asset portfolios.

Establishing whole-of-department plans

Establishing a whole-of-department asset management plan was a common starting point to implementing the AMAF across departments:

- Only DET had any whole-of-department asset management plan documents in place before the introduction of the AMAF.

- Five of the other six departments developed them in response to the AMAF requirements.

- DHHS chose not to develop a whole-of-department asset management plan or other asset management system elements. Instead, it relied on managers of its different asset classes to do this. This approach meant the department was not in a strong position to direct or control asset management activities across its five asset classes.

The departments' whole-of-department asset management plans ranged from a single document that aimed to describe the policy, strategy, and the system of processes and controls to having separate documents for these. For five of the six departments that had whole-of-department plans, the overall approach aligned with the complexity of their asset holdings.

Content of the plans

The AMAF is non-prescriptive. This allows agencies the flexibility to manage their assets according to their own operational environments and the nature of their asset bases. In practice, agencies can find it challenging to know whether an approach is appropriate to meet the AMAF's aims and principles and to support compliance.

Our assessment of the content of the whole-of-department asset management plans identified that only DEDJTR had a comprehensive plan at the time of the 2018 attestation.

It is not surprising that other departments did not have a comprehensive whole-of-department plan by then, as it is a new approach for them. Most have continued to improve their plans since the attestation.

DEDJTR's plan was comprehensive because it:

- largely addressed the mandatory requirements

- contained enough department-specific information and references to relevant policies and procedures to adequately guide asset management across its asset classes.

We identified examples of good practice for different components of the plans across the other departments. Weaknesses in content were common across most departments. Appendix C describes these characteristics.

One component of the whole-of-department plan that many of the departments struggled with was describing an asset strategy over the entire asset base and asset lifecycle, which is one of the AMAF's mandatory requirements for agencies. The AMAF and its implementation guidance outline what agencies should consider in developing the strategy component. Departments determine what they need to include in their whole-of-department strategy and what is more appropriately included in plans specific to individual asset classes.

Figure 2E provides a good practice example of an approach to the strategy component of a whole-of-department asset management plan, based on what we found in department documents and the AMAF implementation guidance.

Figure 2E

Good practice: Strategy component of a whole-of-department asset management plan

|

Good practice at a whole-of-department level means that the department understands:

Including this strategic information in the plan increases staff awareness of expectations, since the whole-of-department plan has wider exposure than an implementation plan or asset class plans. Appropriate asset management strategies for the asset classes or portfolio agencies would underpin this approach. Depicted below is one example of a good department-level approach. Source: DEDJTR Asset Management Strategy. |

Source: VAGO, based on AMAF guidance and good practices observed in departments.

Departments can also improve their whole-of-department asset management plans by incorporating more specific information on how they identify and manage asset risks. Figure 2F describes a good practice example, based on published literature on managing asset-related risks.

Figure 2F

Risk management and contingency planning

|

Some departments referred to corporate risk frameworks as the basis for their asset risk assessment. However, they did not typically refer to the application of risk assessments in determining which assets are critical to agency performance. Critical assets are those that would have significant consequences if they failed—for example, a bridge. Identifying critical assets enables an agency to determine asset management strategies for, and prioritise expenditure on, those assets that pose the greatest risk. Asset criticality assessment is a useful tool for identifying critical assets. Criticality assessments can be applied at the departmental level to assess the department's asset risks and can be depicted visually using a 'heat map'. Criticality assessments can also be applied by asset class to gain a better understanding of risk exposures and enable management strategies or actions to be determined. Note: The 'A' points indicate the relative allocation of risk across the different asset classes. Conventional risk (likelihood and consequence) matrices can be used to support asset risk and criticality assessments provided they contain appropriate consequence categories, such as worker and public safety, customer or community service, or financial or regulatory compliance impacts. The resulting risk profiles also need to be considered against a department's risk tolerance statement to determine acceptability. Risk profiling in asset classes can best be performed using asset information and data collected to highlight condition and performance. Asset management strategies best suited to manage the relative criticality of assets can then be identified in line with the department's asset risk tolerance—for example, 'we plan to avoid failure of critical assets'. Depending on the criticality rating, appropriate management strategies can range from asset performance and condition monitoring, predictive maintenance and planned replacement for critical assets to fix-on-fail strategies for non-critical assets. |

Source: VAGO.

Appendix C provides examples of good practices for two other important areas of the AMAF—asset information and performance monitoring—for which we found common weaknesses across most departments.

Updates to asset management plans

All departments have continued to implement the AMAF since the 2018 attestation. Three of the five departments where we identified multiple weaknesses have improved or started improving their whole-of-department asset management plans.

DHHS advised us that it sees the merit in having a whole-of-department asset management plan and intends to develop one when its asset class plans are completed.

2.4 Leadership

The AMAF identifies that 'effective asset management is supported by organisational leaders who promote the principles and policies of asset management'. Half of the AMAF's 41 mandatory requirements and a third of its good practice guidance points relate to leadership. These include the need for senior leaders to:

- drive the application of the AMAF, the agency's asset management system and any supporting policies

- drive a culture of continuously improving asset management

- proactively promote the implementation of the AMAF and asset management more broadly in the agency to ensure that asset management adds value and is not just a compliance process.

The audit assessed the extent to which senior leaders who have asset management responsibilities—such as deputy secretaries—were involved in applying the AMAF and checking compliance with it.

Figure 2G summarises examples of good leadership by senior leaders in three departments. Senior leadership and accountability for asset management was less visible in the remaining four departments.

Figure 2G

Good leadership practices

|

Leadership actions that drive the AMAF include secretaries:

Other leadership actions that drive the AMAF include:

|

Source: VAGO.

Examples of implementation issues linked to senior leaders being inadequately engaged included:

- departments not strongly engaging with DTF's AMAF implementation working group meetings

- when senior leaders advised us that the introduction of the AMAF did not affect the on-ground staff, who needed to maintain their assets every day regardless of the AMAF

- where there was no identifiable implementation of AMAF by asset classes

- when the funding for projects to improve asset management was not approved, senior leaders in one department made funding available from other business areas, while those in another department decided to put the project on hold.

Two of the three departments in which senior leaders were more visibly or actively engaged in the AMAF's implementation and compliance are also the departments that have better approaches to implementing the AMAF and whole-of-department asset management plans.

3 Checking compliance

Key requirements for agencies to comply with the standing directions include:

- conducting an annual assessment of compliance with all applicable requirements, including the requirement to apply the AMAF

- attesting to financial management compliance and disclosing all material compliance deficiencies in their annual reports

- taking remedial action to address any compliance deficiency, whether material or not.

DTF also requires departments to report to it annually on their financial management compliance and that of their portfolio agencies.

Departmental secretaries and audit committees have key responsibilities to assure the reliability and accuracy of compliance assessments and attestations.

The standing directions instructions explain that these requirements are designed to 'improve rigour in compliance assessment, ensure action is taken to improve identified compliance weaknesses … and increase transparency'. The standing directions guidance explains that agencies are expected to 'take a practical, risk-based approach to demonstrating compliance' for their annual compliance assessments, provide the assessments to their audit committees and use the assessments to inform their annual compliance reports to DTF.

Departments need well-designed arrangements to assure compliance and support reliable attestations. In this Part, we examine the assurance approaches used by departments and their audit committees. Figure 3A highlights the main steps of the attestation process.

Figure 3A

The main steps in the attestation process

Source: VAGO.

3.1 Conclusion

Five departments used reliable approaches to assure their compliance and support their 2018 attestations. The remaining two departments do not have enough detail in their approaches to be able to assess whether they comply with the AMAF, given the criticality, complexity and risks related to their assets.

The attestation itself does not indicate how well departments are complying with the AMAF. This is because the standing directions require agencies to say they comply even when they have not met all mandatory requirements, unless the department considers that non-compliance for one or more mandatory requirements is significant or material.

All departments have weaknesses in the reliability or accuracy of their compliance assessments, such as gaps in their oversight arrangements or not having the right evidence to show compliance. Departments that involve senior leaders with asset management responsibilities in overseeing compliance are more likely to demonstrate better assurance practices and have more reliable and accurate compliance assessments.

Audit committees' limited record-keeping makes it hard for them to show how they apply a risk- and evidence-based approach to their review role or how they satisfy themselves that departmental compliance assessments and attestations are accurate.

3.2 Departments' 2018 attestation results

Two departments reported a material compliance deficiency for the AMAF in their 2017–18 annual reports—DET for school buildings and DHHS for the assets of its health building authority.

The standing directions instructions mandate that the attestation wording includes:

- a brief summary of the reasons for, or circumstances of, the material compliance deficiency

- details of planned and completed remedial actions.

The way DET and DHHS provided this information in their attestations differed:

- DET identified that its deficiency related to school assets was material because the AMAF had not yet been applied across all schools, but it had a five-year plan to address this.

- DHHS identified that it had a material deficiency and that this would be addressed by December 2018, but did not explain which asset class(es) this related to or what made it material.

The limited information in DHHS's attestation does not provide transparency about the nature of the deficiency.

Determining if material compliance deficiencies exist

The focus of the attestation is on identifying any material compliance deficiencies and actions to address them. DTF's guidance to agencies on materiality and the AMAF provides an example about a major telecommunications distribution cable—any failure is likely to disrupt service delivery over a wide area and damage agency finances and reputations, and would therefore be material. However, if the computer systems in the telecommunications retail provider failed, it would inconvenience customers by closing shopfronts, but the telecommunications service would continue, and would therefore be non-material.