Education Transitions

Overview

This audit assessed whether the Department of Education and Training (DET), government schools and early childhood education and care providers are effectively supporting children to transition into Prep and from primary to secondary school.

DET has improved access to high-quality kindergarten programs and has developed a comprehensive, well-researched framework to support early-years transitions. These actions have contributed to improved outcomes for children transitioning into Prep. However, DET does not have a similar strategy or framework for managing middle-years transitions and despite some pockets of improvement, engagement and academic outcomes continue to decline as children move into secondary school.

In an environment where schools have high levels of autonomy, DET needs to provide strong leadership, including sound guidance, appropriate support and effective monitoring of schools. It does not consistently do so.

Despite this, there are many examples of good practice among schools and early childhood education providers. These include innovative curriculum and teaching approaches, joint professional development forums with school and early childhood teachers, and schools that set and monitored academic achievement targets for transitioning students.

System-wide change is required if consistent long-term gains are to be made, and if issues such as the uneven impact of transitions on male and female students are to be resolved. The report recommends a range of simple cost effective steps that DET could take to better support schools to improve middle-years transitions, and highlights some of the examples of better practice found in audited schools.

Education Transitions: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2015

PP No 24, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Education Transitions.

This audit assessed whether the Department of Education and Training (DET), government schools and early childhood education and care providers are effectively supporting children to transition into Prep and from primary to secondary school.

The audit found that DET has improved access to high-quality kindergarten programs and has developed a comprehensive, well-researched framework to support early-years transitions. These actions have contributed to improved outcomes for children transitioning into Prep. However, DET does not have a similar strategy or framework for managing middle-years transitions and despite some pockets of improvement, engagement and academic outcomes continue to decline as children move into secondary school.

System-wide change is required if consistent long-term gains are to be made, and if issues such as the uneven impact of transitions on male and female students are to be resolved. My report recommends a range of simple, cost-effective steps that DET could take to better support schools to improve middle-years transitions, and highlights some of the examples of better practice found in audited schools.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

18 March 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Kristopher Waring—Engagement Leader Mary O'Brien—Audit Manager Teri Lim—Senior Analyst Stefania Colla—Analyst Jason Cullen—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Dallas Mischkulnig |

Successful transitions into and between schools can make or break a young person's educational experience. The transitions into Prep and from primary to secondary school mark key stages in young peoples' development and in their engagement with the education system. Poor transitions can lead students to disengage and result in poorer educational outcomes. Some children—such as Aboriginal children, children with disabilities, boys and children from low socio-economic backgrounds—are at greater risk of suffering from a poor transition.

To transition well, a child needs to understand what the next stage in their education looks like and they need to be prepared for the level and style of work expected of them at the next stage.

The challenge for early childhood education and care providers and for schools is to prepare students for the move, to make sure that their information is transferred as efficiently and effectively as possible, and to support them to settle into their new school environment.

My audit examined how well early childhood education and care providers and schools support children to make successful transitions. It also looked at how effective the Department of Education and Training (DET) has been in supporting, guiding and monitoring early childhood education and care providers and schools.

It was pleasing to find many examples of good practice including innovative curriculum and teaching approaches, joint professional development forums with school and early childhood teachers, and schools that set and monitored academic achievement targets for transitioning students. However, I also found great variation in the approaches adopted by schools, highlighting both the risks and the benefits of school autonomy.

In an environment where schools have high levels of autonomy, DET needs to provide strong leadership, including sound guidance, appropriate support and effective monitoring of schools. It does not consistently do so.

I found that DET has developed a comprehensive and well-researched framework to support early-years transitions. This has led to a greater uniformity of approach and contributed to improved early-years transition outcomes. However, it does not provide the same levels of support and guidance to schools to transition students from primary to secondary school. While there have been modest improvements in some middle-years transition outcomes over the past seven years, these are not consistent. Given the lack of attention from DET these can only be attributed to the schools themselves tailoring their delivery of education to their students.

System-wide change is required if consistent long-term gains are to be made, and if issues such as the uneven impact of transitions on male and female students are to be resolved. There are simple and cost-effective steps that DET could take to better support schools to improve middle-years transitions.

My report makes seven recommendations, including that DET provide better advice to schools on middle‑years transitions and develop better systems for monitoring children's outcomes as they progress through school. I am encouraged to see that DET has already started to address some recommendations and has provided a detailed plan of action including deadlines for all recommendations. I look forward to the opportunity to review the outcomes of these actions in the future.

I would like to thank the schools and early childhood education and care providers that were visited by my audit team and the DET staff who provided the evidence required for this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

March 2015

Audit Summary

Background

There are a number of key transitions during young peoples' education that shape their learning, development, wellbeing and engagement with school. The two key transitions occur when children move into the Prep year of primary school and when they move from primary into Year 7 of secondary school. Other transitions that can affect a child's school experience include when they transition from grade to grade within a school and when they move between schools.

While a transition is generally considered to be a single event or year of schooling, the process of transitioning usually occurs over a more extended period of time. It involves preparing the child to move, transferring them and their information, and a period after the move during which they settle into their new year level or school. The transitioning process can be both challenging and transformative for the child. The effect on the child's academic outcomes and engagement with school can be monitored to provide an indication of how successfully the transition was made.

The transition into Prep marks the start of a child's formal full-time education and the move away from play-based learning into a more structured learning environment. The move from primary to secondary school usually occurs around the onset of puberty, a time of significant developmental change in the middle years—Year 5 to Year 8. This increases the likelihood of difficulties in adjusting, and can ultimately impact on learning outcomes.

The success of a transition is likely to be influenced by a broad range of factors—including prior learning and achievement, socio-economic and cultural background, disability and learning difficulties, and gender.

The objective of the audit was to examine how effectively early childhood education and care providers, schools and the Department of Education and Training (DET) are supporting the transitions of children in the education system. The audit examined whether DET has developed and implemented an effective and well-researched approach to support schools and early childhood education and care providers, and whether they in turn efficiently and effectively support children and their families during transitions.

Conclusions

DET has developed a comprehensive, well-researched framework to support early‑years transitions. It has improved access to high-quality kindergarten programs and has provided funded programs and resources to support schools. These actions have contributed to improved outcomes for children transitioning into Prep, including their developmental status and academic readiness for school.

In contrast, DET does not have a strategy or framework for managing middle-years transitions. Despite the overall pattern of a decline in engagement and academic outcomes as children move into secondary school, there are some encouraging outcomes associated with middle-years transitions. These include improvements in children's' engagement with school and parents' opinions on how well the schools transitioned their child.

DET's Strategic Plan 2013–17 emphasises the importance of middle-years transitions and its school funding model encourages schools to focus on improving middle-years outcomes. However, it provides little general guidance to schools on how to effectively transition middle-years children. The guidance that it does provide is limited to focusing on supporting transitions for vulnerable cohorts of children, such as those with additional learning needs.

Schools face significant challenges in dealing with student transitions including efficiently transferring and accessing student information, establishing and maintaining effective communications with other schools and early childhood education and care providers, and monitoring student outcomes. The extent to which schools have been effective in dealing with these challenges varies significantly and is highly dependent on the capabilities of the school staff and leadership team. Without a mechanism for better practice being identified and shared, the opportunities for schools and DET to engage in continuous improvement are limited. However, the better support provided by DET for early-years transitions is associated with improved performance in this area.

While the push to increase school autonomy has resulted in some innovative approaches from schools to tackle transition challenges, greater support is needed from DET, particularly for middle-years transitions.

Findings

Transition outcomes

Early-years outcomes have improved

Prep teachers are increasingly assessing new Prep children as being ahead of the expected levels in English and mathematics. In 2013–14 almost all children in Victoria were assessed by their Prep teachers as being at, or six months above, the expected level in English (99 per cent) and mathematics (97 per cent). This standard has been maintained over the past five years.

Since the first assessment in 2009, Victoria has reduced the proportion of Prep children who are considered developmentally vulnerable on one or more of the Australian Early Development Census domains—previously known as the Australian Early Development Index. In 2012, Victoria had the lowest proportion of any state (19.5 per cent), however, this still equates to one in five children entering school with at least one assessed developmental vulnerability. Vulnerable cohorts are particularly at risk of falling further behind during transitions.

Kindergarten participation is strongly associated with improved performance in both developmental and academic readiness for schools. Over the past five years, kindergarten program participation levels have risen from 93 per cent to 96 per cent. DET has exceeded its Budget Paper target each year since 2009, although there are weaknesses in the current measure. More could be done to monitor how well children and their families engage with kindergarten throughout the year, and to assess the quality and effectiveness of particular kindergarten programs. This information would better inform DET's actions to improve early‑years transitions.

Mixed outcomes for middle-years students

For middle-years transitions, a range of academic and wellbeing outcome data is available, including academic performance, engagement with school and parents' assessment of children's transitions.

The two key measures of academic achievement are:

- teacher assessments of performance against the Australian Curriculum/Victorian Essential Learning Standards

- the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) results.

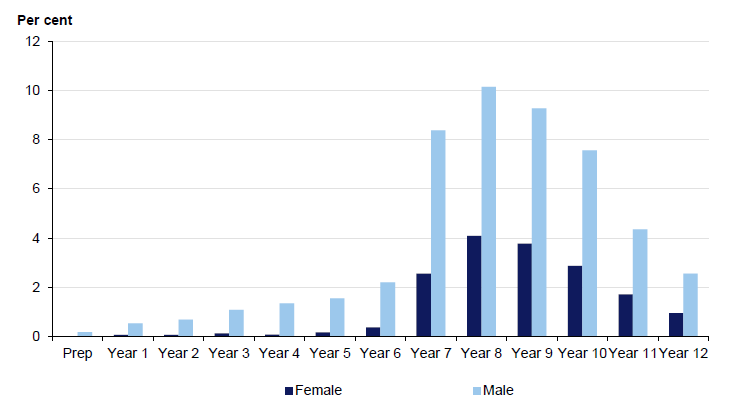

Performance across these two measures is mixed. While teacher assessments show a drop in performance immediately following the middle-years transition, NAPLAN results show improvements in literacy and numeracy over the same period. However, the NAPLAN writing results appear to be significantly impacted by the transition—with boys most heavily affected.

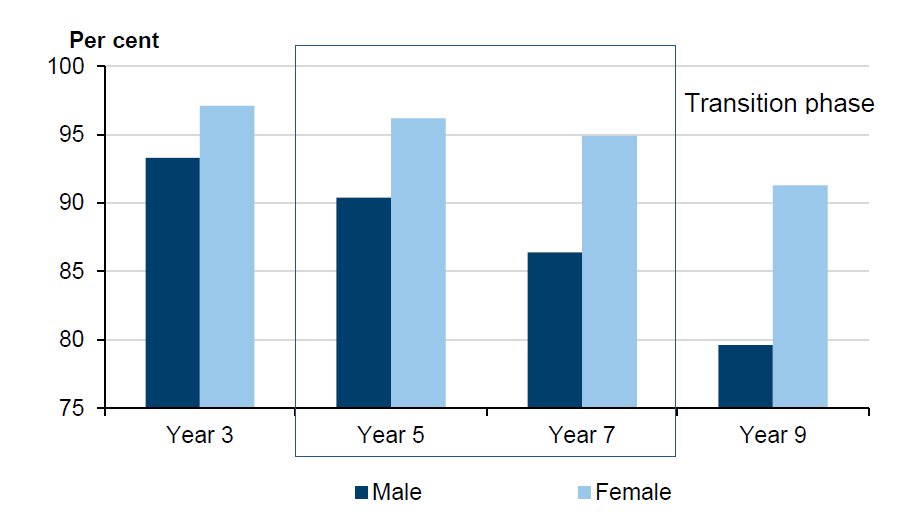

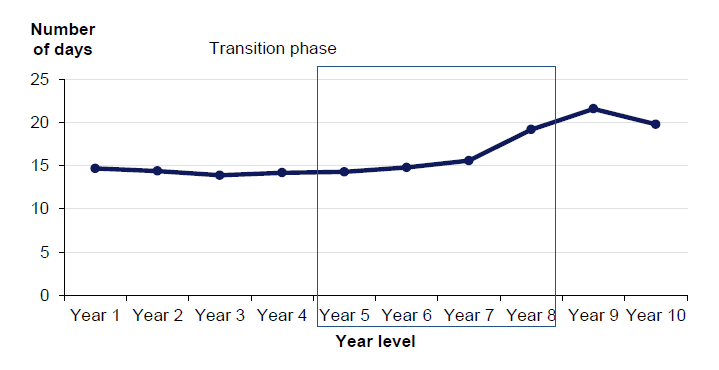

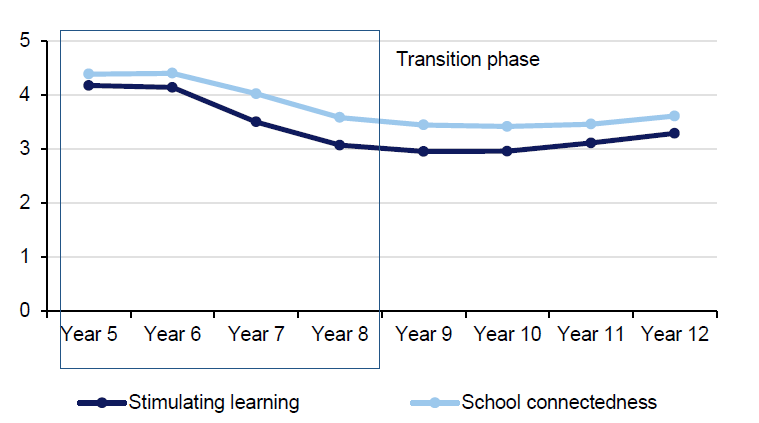

There has been a steady overall increase in student engagement with school since 2007. However, there is a notable drop in engagement across the middle-years transition period that has not changed over time. Engagement is strongly correlated with academic achievement.

Despite the widely reported discrepancies in performance between boys and girls around the middle-years transition, DET has not prepared gender-specific guidance for schools. Notably, only one of the eight audited secondary schools monitored gender-based student outcomes. It is difficult to see how DET can expect schools to address this known gap unless it provides clear guidance and improved support to schools to monitor and address the issue.

More needs to be done to address transition challenges

Poor and inconsistent practices for transferring student information

The timely and accurate transfer of academic, engagement and personal information student performance information is critical to the success of a transition. In early‑years transitions, DET has taken a significant step towards facilitating this by introducing a standardised Transition Learning and Development Statement (transition statement) for all children. However, it has not produced a comparable document for middle years, meaning that primary schools prepare material in multiple formats and with varying levels of detail to suit the differing needs of secondary schools.

The timely transfer of information is further hampered by various factors:

- Schools lack understanding about the use and disclosure of information—including compliance with privacy legislation—and there is a corresponding lack of consistency in practice. DET has not provided clear guidance and schools are unsure about what information they can transfer and what permissions they need to do so. As a result, student information is not being transferred as efficiently, effectively or completely as it could be.

- Schools have varying capacities to develop and maintain good relationships with the large numbers of early childhood education and care providers and schools their students transition from. This increases their reliance on written information including, for early years, information in transition statements.

- Schools lack dedicated staff resources to transfer academic, engagement and personal information on each child. Only one of the audited schools had resources dedicated to managing or supporting transitions.

To address these barriers DET needs to:

- provide clearer guidance about information disclosure and privacy legislation

- work closely with schools to understand the information needs and challenges associated with middle-years transitions

- standardise the transition of middle-years student information.

Better support needed for vulnerable cohorts

DET provides guidance, funding and support to assist specific groups of vulnerable students to transition effectively into and between schools. These groups include:

- children with additional or complex needs

- gifted and talented children

- children with a language background other than English

- children from Aboriginal backgrounds—in this report the term Aboriginal refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Support for these groups has improved over time, but without more detailed, accurate and timely outcomes information, it is not possible to know what impact this support is having.

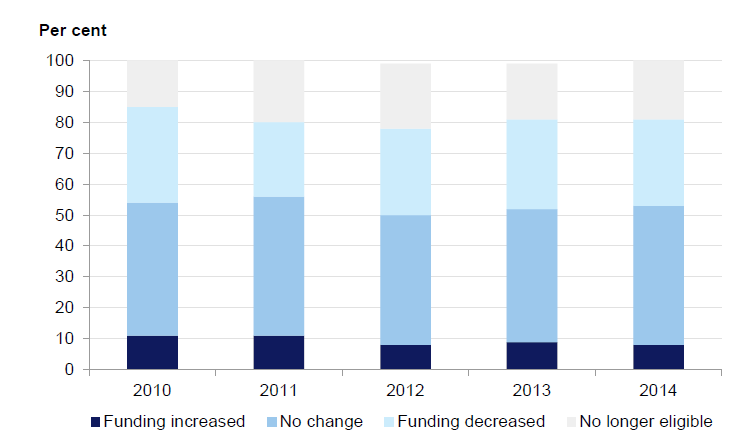

DET funds a range of early childhood programs designed to assist students to prepare for the transition to school. While it does not fund specific middle-years transition programs, in 2008 it revised its school funding model to weight it more towards the middle years. It is not clear how schools have applied this weighted funding to support transitioning middle-years students.

DET's most significant funded program is the Program for Students with Disabilities (PSD). This $640 million program supports 22 000 government school students with disabilities. However, each child with PSD funding has this reviewed in Year 6. This means that about half of all PSD students have their funding and support modified or cancelled in the period leading into a major transition. Holding the review in Year 7—once the student has transferred into secondary school—would allow a more accurate assessment of their needs in their new school environment.

More needs to be done to understand transition outcomes

It is important that DET has a good understanding of transition-related outcomes so that it can design policies, programs and approaches to address issues that arise. However, it does not routinely examine outcomes for transitioning students and has no reliable information about the outcomes of particular approaches, strategies or methods used by schools. As such, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the outcomes reported in this audit are a direct result of specific actions designed to improve transitions.

While the Victorian Student Number now allows DET to collect and report more reliable student-level data, it does not extend back into early childhood education and care providers. Therefore, it is not currently possible to link participation in early childhood services to early school performance. DET has advised that it plans to improve child‑level monitoring, which will allow this linkage to occur.

Similarly, early childhood education and care providers and schools need access to timely, relevant data to understand whether their actions are effective. In April 2013, DET launched a new School Information Portal to replace the Performance Assessment Report it previously provided to schools. This new system provides schools with improved access to a wider range of performance information.

While this is a significant step forward in allowing schools to better monitor their performance, none of the audited schools had evaluated their approach to transitioning students using this information.

It is clear that early childhood education and care providers and schools are managing transitions well overall. However, DET's current approach to supporting, guiding and monitoring early childhood education and care providers and schools is not helping to break down some of the more entrenched transition outcomes. A new approach is needed to address these issues. Having achieved sustained improvement in some areas, DET now needs to start focusing on tackling the areas where no gains have been made, including where there are differences in outcomes based on gender, geographic location, culture and language.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

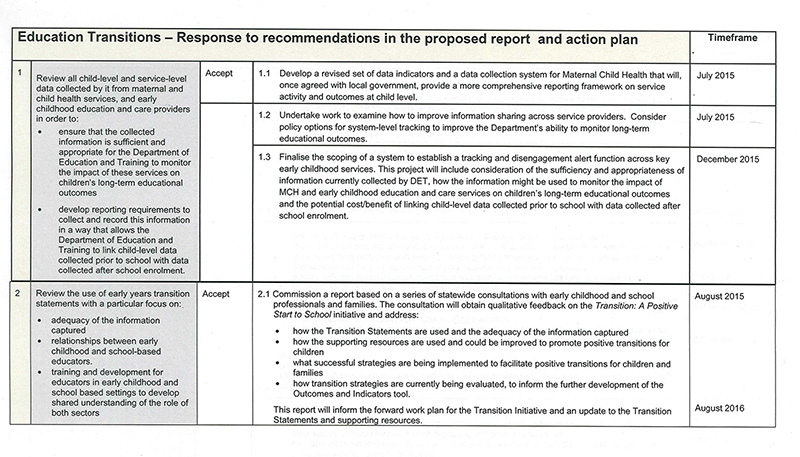

- reviews all child-level and service-level data collected by it from maternal and child health services, and early childhood education and care providers in order to:

- ensure that the collected information is sufficient and appropriate for the Department of Education and Training to monitor the impact of these services on children's long-term educational outcomes

- develop reporting requirements to collect and record this information in a way that allows the Department of Education and Training to link child-level data collected prior to school with data collected after school enrolment

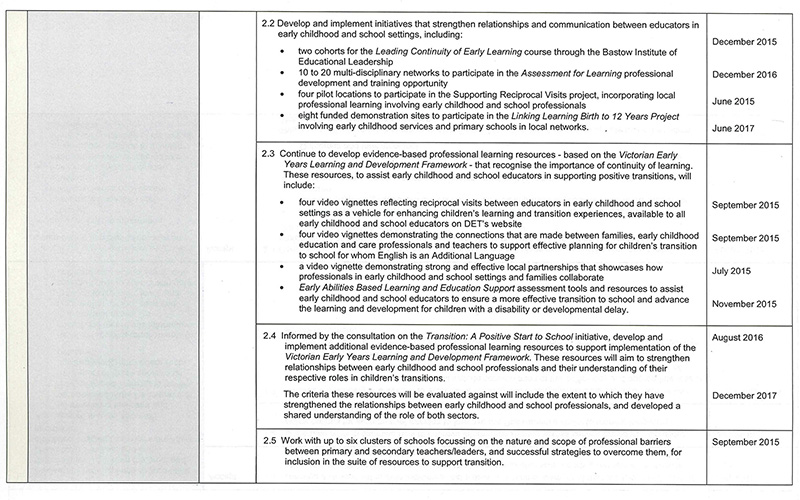

- reviews the use of early-years transition statements with a particular focus on:

- adequacy of the information captured

- relationships between early childhood and school‑based educators

- training and development for educators in early childhood and school-based settings to develop a shared understanding of the role of both sectors.

That the Department of Education and Training:

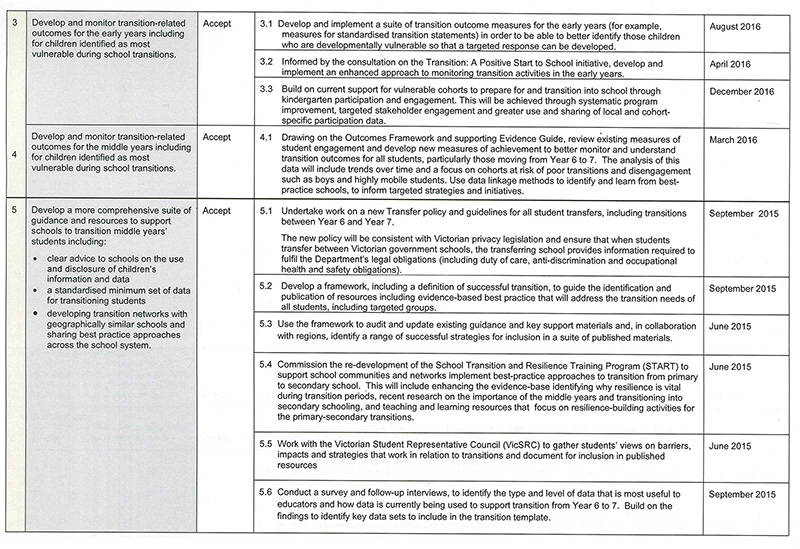

3 & 4. develops and monitors transition-related outcomes for both the early years and the middle years including for children identified as most vulnerable during school transitions

- develops a more comprehensive suite of guidance and resources to support schools to transition middle-years students, including:

- clear advice to schools on the use and disclosure of children's information and data

- a standardised minimum set of data for transitioning students

- developing transition networks with geographically similar schools and sharing best practice approaches across the school system

- reviews and improves its systems to allow more timely access to child-level data for schools

- examines the appropriateness of the timing of the Year 6 review for children who receive funding under the Program for Students with Disabilities, and its impact on transition outcomes.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we provided a copy of this report to the Department of Education and Training with a request for submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. The Department of Education and Training's full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 The importance of successful transitions for children

The importance of children making successful transitions into and between schools is widely acknowledged and the success of a transition is influenced by a broad range of factors, including prior learning and achievement, socio-economic and cultural background, disability and learning difficulties, and gender.

There are a number of educational transitions that shape a young person's learning, development, wellbeing and engagement with school. The two key transitions occur when children move into the Prep year of primary school, and when children move from primary to Year 7 of secondary school. Other transitions that can affect a child's school experience include when they transition from grade to grade within a school and when they move between schools.

The two key transitions occur at times of significant developmental change. The transition into Prep marks the start of a child's formal full-time education and the move away from play-based learning into a more structured learning environment. Meanwhile, the move from primary to secondary school often occurs around the onset of puberty.

1.2 Understanding transition

While a transition is generally considered to be a single event—where a child moves between sectors (early childhood education and care to school) or schools (primary to secondary)—the process of transitioning covers a longer period of time, and can be both challenging and transformative. For example, the skills a child learns in kindergarten can influence how quickly and effectively they transition into school.

The actions of the school to support a child in the months and years following their transition can also have a significant impact. It is therefore important not to consider a transition simply as a process of transferring a child from one setting to another, but as a series of interconnected processes taking place over an extended period of time.

Broadly speaking, the same principles apply to making any transition successful:

- Preparation—preparing the child to move. Making sure they have the relevant social, emotional and developmental skills needed to progress to the next stage of their education. Providing guidance and advice on the transition experience and making effective introductions to their new educational environment.

- Transfer—transferring the child from one setting to another. Making sure that the child, their families and the receiving school have all of the information they need to ensure an effective transfer.

- Induction—settling the child into their new learning environment, and identifying and providing any additional support needed.

- Consolidation—continuing to monitor the child's learning and developmental outcomes and engagement, and providing any additional support needed.

1.3 Early-years transition

One of the key initiatives implemented across all Australian jurisdictions to drive improved transition outcomes for Prep students has been to increase the levels of participation in kindergarten programs. In 2014, around 96 per cent of four-year-old children in Victoria were enrolled in a kindergarten program.

Kindergarten programs play a critical role in a child's learning and development including their social and emotional skills, self-awareness, language, literacy and numeracy skills—all of which are critical to helping children settle quickly and effectively into a school environment. Attending high quality kindergarten programs has been shown to have a positive impact on a child's later school-based outcomes.

In 2014, 74 826 Victorian children moved from early childhood education and care or home-based settings into primary school, with 51 222 of those (68 per cent) starting Prep in a government school.

1.4 Middle-years transition

There has been growing awareness of the importance of 'the middle years'—defined as spanning Year 5 to Year 8—on a child's learning experiences.

The transition from primary school to secondary school occurs during these middle years and involves significant change for a child and their family. While the majority of children make this transition without disruption to their wellbeing or learning, many experience a drop in achievement and engagement with school in the years following this transition.

International research suggests that this negative impact may be cumulative—existing gaps are likely to be widened—and may signal the beginning of later disengagement from secondary school. Australian research also shows that as a child progresses through the middle years of school they report a decrease in psychological health. A quarter of Western Australian children surveyed by Edith Cowan University in a study published in 2014 found the transition from primary to secondary school difficult.

Our examination of middle-years transitions focuses on the activities of primary schools preparing children for transitioning to secondary school and the activities of the secondary schools receiving those children.

In 2014, 65 924 Victorian children started Year 7 at a secondary school. Of those, 35 675, or 54 per cent, did so at a government school.

Photograph courtesy of hxdbzxy/Shutterstock.com.

1.4.1 Providers involved in transitions

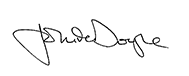

The non-government sector is responsible for providing the vast majority of kindergarten programs for children. Local government services cover 18 per cent of enrolments, while government schools providing a kindergarten program represent only 2 per cent of total enrolments.

Government schools are the main providers of primary schooling for children in Victoria. However there is a far more even distribution of children across government and non-government schools in the secondary sector. Figure 1A shows the involvement of government and non-government providers at each stage of a child's education.

Figure 1A

Enrolments by provider

Note: 'Community and private' providers of kindergarten services include both Catholic and independent schools.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office's analysis of 2013 kindergarten and 2014 school enrolment data.

1.4.2 Other significant transitions

In addition to these two key transitions, a large number of school-aged children also experience transitions when they move:

- from one school to another—approximately 10 per cent of children from each year level move each year—55 468 children in 2013

- into and out of specialist schools—2 269 children started, and 1 795 exited a specialist school in 2013

- into and out of English language schools—3 263 children started, and 2 831 exited an English language school in 2013—children usually attend for two terms before transitioning to a mainstream school.

1.5 Legislation

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 sets the overarching legislative framework for education and training in Victoria. A key principle of the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 is that all Victorians should have access to a high-quality education. The legislation does not prescribe a process for transitions.

All Victorian preschools are bound by the conditions set out in the Education and Care Services National Law Act 2010 or the Children's Services Act 1996 as well as the Education and Care Services National Regulations 2011 orChildren's Services Regulations 2009. The Department of Education and Training (DET) licences early childhood education and care services including preschool, long day care, family day care, occasional care and outside school hours care services. Services must meet the National Quality Standard (Schedule 1 of the Regulations), as well as all regulations and conditions of applications for licences covered under the Education and Care Services National Regulations or theChildren's Services Regulations.

In order to receive Victorian State Government funding, preschools must be licensed to operate a preschool program that meets the criteria for funding eligibility.

1.6 Roles and responsibilities

1.6.1 Department of Education and Training

DET is the key agency responsible for the delivery of educational outcomes in Victoria, including for early childhood and school education. It provides funding to government schools to cover the cost of providing free instruction in the core curriculum—including infrastructure, staffing and school resources—and separately funds specific programs designed to meet the individual learning needs of children, both prior to and within the school system.

In addition DET's role is to:

- license and regulate education and care services as required by relevant acts and regulations

- develop and deliver policy, guidance and support that enables schools and early childhood education and care providers to support children

- monitor and oversee the performance of schools and early childhood education and care providers and determine whether the educational outcomes of children are being maximised.

The Compact: Roles and responsibilities in Victorian government school education, (the Compact) sets out the key responsibilities of both DET and schools. It requires schools to:

- establish networks and partnerships with families as well as early childhood education and care providers and other schools to strengthen student engagement and support transitions

- demonstrate sustained improvement in student engagement and wellbeing

- collect and report on engagement and other data that support monitoring, reporting and student transitions.

1.6.2 Government schools

Under the Compact, government schools have broad responsibilities related to transitions—including demonstrating sustained improvement in student engagement and wellbeing, and tracking children's data, including any movement to a different setting. In Victoria there are:

- 1 127 government primary schools

- 239 government secondary schools

- 77 government primary-secondary schools

- 79 government specialist schools

- eight government English language schools or centres.

1.7 Funding and support

1.7.1 Early years

Australian and international research suggests that learning experiences in the years prior to starting school—and in the early years of school—are critical to a child's long-term success at school. As a consequence, Australian governments have increased the investment in early childhood education and care significantly over the past decade. Across all state and territory governments, $1.4 billion is spent annually on early childhood education and care. DET reported that its expenditure for the 2013–14 financial year for early childhood education was $367.5 million. This figure includes per capita grants, kindergarten fee subsidies and specialist program funding.

1.7.2 Middle years and students with disabilities

DET provides the delivery of education to children in Victoria by giving funding directly to schools. DET funds government schools through the Student Resource Package. In 2014, the Student Resource Package allocated over $5 billion to schools, comprising student-based funding, school-based funding, and targeted initiatives. The standard funding component for each child in a school is weighted to recognise the different costs associated with different year levels. The level of funding provided for students in Years 7 and 8 who have just transitioned to secondary school was increased to the same level as students in Years 9 to 12, to encourage schools to invest in early intervention.

DET also administers $640 million in funding under the Program for Students with Disabilities for children from Prep through to Year 12. This cohort of children is considered to be at a higher risk of making a poor transition.

Further information about DET's school funding arrangements are available in VAGO's Victorian school funding explained information piece, published in February 2015 as an appendix to the performance audit report Additional School Costs for Families.

1.8 Audit objective and scope

This audit examined how transitions into and between early childhood education and care and school, and between schools are managed. It examined DET, as the agency responsible for policy and initiatives that guide student's transitions, along with a sample of early childhood education and care providers and schools.

The audit focused on the most significant transitions that all children make—into primary school for the first time and into secondary school. It also examined activities undertaken by English language schools and specialist schools. The transitions that children make annually as they progress to the next year level were not considered as part of this audit.

The objective of the audit was to examine how effectively early childhood education and care providers, primary and secondary schools and DET are supporting the transitions of children in the education system. To evaluate this objective, the audit assessed whether:

- DET has developed and implemented effective and well-researched policies, strategies and approaches to support schools and early childhood education and care providers to manage transitions efficiently and effectively

- education providers efficiently and effectively support students and their families to transition into and between schools.

1.9 Audit method and cost

The audit involved research, document and file review, and interviews with DET staff and stakeholders. The audit also selected a range of schools, taking into account factors such as their region, proximity to other government and non-government schools, socio-economic status, receipt of transition-related funding and performance against transition-related indicators. In total, the audit examined the practices of 30 schools and early childhood education and care providers, as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Providers or schools visited during the audit

|

Type of provider |

Number |

|---|---|

|

Government secondary school |

6 |

|

Government primary school |

10 |

|

Government Prep to Year 12 or Kindergarten to Year 9 school |

2 |

|

Government English language school |

2 |

|

Government specialist school |

2 |

|

Kindergarten program provider(a) |

6 |

|

Independent Prep to Year 12 or Kindergarten to Year 12 school(a) |

2 |

|

Total |

30 |

(a) Providers not associated with DET.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The total cost of this audit was $495 000.

1.10 Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines activities and outcomes associated with early-years transitions

- Part 3 examines activities and outcomes associated with middle-years transitions

- Appendix A outlines transition activities in the early years

- Appendix B outlines transition activities for Years 6–7.

2 Early-years transition

At a glance

Background

A well-researched, system-wide approach to transitioning children is needed to support schools in minimising the negative impact of transitions and making sure that vulnerable children are not disadvantaged.

Conclusion

The Department of Education and Training (DET) has implemented a robust and comprehensive approach to supporting early-years transitions. While outcomes are improving, DET does not adequately monitor the impact of transitions. This means it cannot easily identify and support vulnerable cohorts of children or drive system-wide improvement.

Findings

- DET has a well conceptualised approach to early-years transitions that facilitates transferring information with the child, through a transition statement.

- Despite improvements in kindergarten participation, one in five Victorian children start their first year of school with a developmental vulnerability.

- Children who are Aboriginal, from a language background other than English, or who live in low socio-economic areas are more commonly assessed as having a developmental vulnerability.

- DET does not collect sufficient service-level or child-level data to enable it to understand the relationship between its approach and later outcomes.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- reviews all child-level and service-level data collected by it in order to:

-

- ensure that it can monitor their impact on children's long-term outcomes

- link data collected prior to school with data collected after school enrolment

- reviews the use of early-years transition statements with a particular focus on:

-

- adequacy of the information captured

- relationships between early childhood and school-based educators

- training to develop a shared understanding of the role of both sectors

- develops and monitors transition-related outcomes for the early years.

2.1 Introduction

Children who enter school for the first time require a set of life and learning skills in order to make a successful transition to primary school. Research has established that children who commence school without these basic skills are at risk of poorer academic and social outcomes.

Promoting successful transitions in the early years is not just about the readiness of the child. It requires the involvement of parents and families, communities, early childhood education and care providers, as well as schools.

The Department of Education and Training (DET) oversees and regulates the early childhood education and care sector, and is the major provider of education to children through government schools.

Early childhood education and care service providers and schools have the autonomy to adopt practices to best support the children in their care. DET's role is to provide advice and guidance on current best practice approaches to support children's successful transitions and to monitor children's outcomes so that improvements to strategies, planning and service delivery can be made.

2.2 Conclusion

Most Victorian children are well prepared for their transition to primary school. Prep teachers' assessments of children's developmental vulnerability and academic preparedness have both improved. However, one in five children still begin school with a developmental vulnerability, and particular cohorts of children—including those from Aboriginal backgrounds, areas with lower socio-economic status, and boys—fare much worse.

The improvements have occurred concurrently with DET's development and implementation of a comprehensive framework for early-years transitions that includes:

- high‑quality guidance and resources for schools, early childhood education and care services and families

- the requirement for schools to complete and issue transition statements for each child

- specifically-funded programs.

However, more could be done to better monitor the quality and effectiveness of kindergarten programs as well as the initiatives DET has in place to encourage a positive transition to school. DET needs to increase its focus on transitions into school for boys, Aboriginal children, students learning English as an additional language, and students from low socio-economic backgrounds.

2.3 Transition outcomes

There are two key measures of transition outcomes for children moving into primary school. These are:

- developmental status—measured by the three-yearly census of Australian children in their first year of school, the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC)—known as the Australian Early Development Index until 1 July 2014

- academic readiness—measured by Prep-teacher judgements against the statewide learning standards.

Kindergarten participation is a key input strongly associated with improved performance in both areas. In Victoria, the proportion of children attending a kindergarten program has increased each year between 2006 and 2013. Over the 2009 to 2012 period, the rate of children defined by the AEDC as having an area of developmental vulnerability in their first year of schooling has declined. Victoria's performance exceeds that of any other Australian jurisdiction. The next AEDC survey is due to be conducted in 2015.

Victorian Prep teachers assessed the literacy and numeracy standards of the majority of their students as being at the expected level, and believe that approximately three‑quarters of Victorian children are adapting well to their first year of school.

However, there is still a sizable minority of children who start their transition to school with a developmental vulnerability that is likely to impact on their later success at school.

2.3.1 Kindergarten participation

Kindergarten programs play a critical role in preparing children to transition into school. They are designed to engage children, to develop their skills in communication, thinking and building positive relationships, and to build their sense of identity and wellbeing.

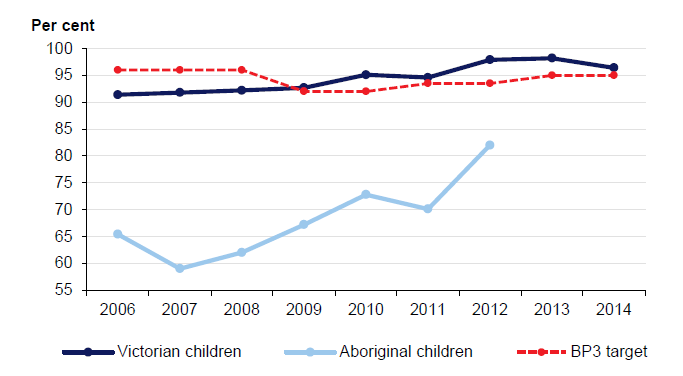

Attendance at kindergarten is not compulsory in Victoria. However, for several years Victoria has been moving towards the nationally agreed target of providing all children with access to a kindergarten program for 15 hours a week in the year before they start school. Consistent with the national agreement, Victoria has set its target for kindergarten participation—as distinct from universal access—at 95 per cent. Figure 2A shows the improvements that have been made in the reported kindergarten participation rate over the last nine years, including significant improvements for Aboriginal children.

Figure 2A

Kindergarten participation rates over time against Budget Paper No.3 service target

Note: Budget Paper No.3 (BP3) target figures are from http://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/State-Budget/Previous-budgets. As BP3 figures are reported by financial year, and participation rate figures are reported by calendar year, we have selected the first year of the BP3 data due to the August kindergarten census being in the first half of the financial year, i.e. the 2006 figure here represents the figure reported in the 2006–07 BP3.

Note: There is no separately reported data available for Aboriginal children since 2012.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data provided by DET, and the DET Annual Report 2013–14 and BP3s (2006–07 to 2014–15).

2.3.2 Assessment of children's development in their first year of school

Developmental status

The Commonwealth Government undertakes a national three-yearly census of all children in their first year of school—the AEDC. This census is completed by Prep teachers and measures children's development in five areas or domains, including:

- physical health and wellbeing

- social competence

- emotional maturity

- language and cognitive skills

- communication skills and general knowledge.

The AEDC was implemented nationally for the first time in 2009 and repeated in 2012. The next data collection will occur in 2015.

Being competent in all five of these domains is considered important to making a successful transition to school. Figure 2B shows that the number of Victorian children in their first year of school who were considered by their Prep teacher to be developmentally 'on track' increased from 55.9 per cent in 2009 to 57.1 per cent in 2012.

Figure 2B

Per cent of Victorian Prep children considered 'on track' by gender over time

|

'On track' on five domains |

'On track' on five domains |

'On track' on five domains |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

Boys |

Girls |

All |

|

2009 |

47.3 |

64.4 |

55.9 |

|

2012 |

48.7 |

65.7 |

57.1 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AEDC data provided by DET.

Figure 2B also shows that boys are far less likely than girls to be developmentally 'on track' when they begin school. In fact, less than half of boys were considered to be developmentally 'on track'. This pattern persists throughout schooling in most indicators.

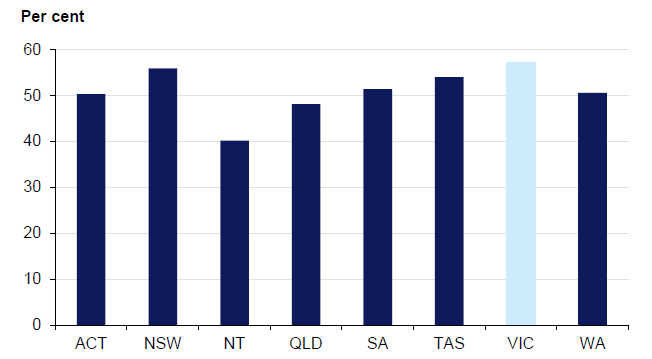

As shown in Figure 2C, Victoria has the highest proportion of children 'on track' on all five developmental domains of any state or territory, closely followed by New South Wales.

Figure 2C

State-by-state comparison of the proportion of children considered developmentally 'on track' in their first year of school, 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AEDC data reported in The state of Victoria's children 2012: early childhood.

AEDC results also provide measures of the proportion of children vulnerable in one or more developmental domains. Figure 2D shows that the proportion of Victorian children rated by their Prep teachers as vulnerable against the AEDC domains had reduced between 2009 and 2012, and is lower than in any other state or territory.

Figure 2D

Per cent of Prep children developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains by state and territory in 2009 and 2012

|

2009 |

2012 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

State/territory |

||

|

Victoria |

20.3 |

19.5 |

|

New South Wales |

21.3 |

19.9 |

|

Tasmania |

21.8 |

21.5 |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

22.2 |

22.0 |

|

Western Australia |

24.7 |

23.0 |

|

South Australia |

22.8 |

23.7 |

|

Queensland |

29.6 |

26.2 |

|

Northern Territory |

38.7 |

35.5 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on the Australian Government 2013. A Snapshot of Early Childhood Development in Australia 2012 – AEDI National Report Re-issue November 2013, Australian Government, Canberra.

Despite this improving trend overall, results for boys, Aboriginal children, children from language backgrounds other than English and students from low socio-economic backgrounds were consistently lower, albeit also showing improvement between 2009 and 2012, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Per cent of Victorian Prep children developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains by population cohort

|

2009 |

2012 |

Significance of |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Boys |

26.4 |

25.2 |

Significant decrease |

|

Girls |

14.1 |

13.8 |

No significant change |

|

Aboriginal |

42.4 |

39.6 |

Significant decrease |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

20.1 |

19.2 |

Significant decrease |

|

Language background other than English |

30.4 |

28.0 |

Significant decrease |

|

English speaking only |

17.8 |

17.3 |

No significant change |

|

Low socio-economic status |

32.0 |

31.5 |

No significant change |

|

High socio-economic status |

14.1 |

12.5 |

Significant decrease |

|

Total |

20.3 |

19.5 |

Significant decrease |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AEDC data. Significance testing by DET.

The AEDC also compiles information from Prep teachers on the success of students' transitions into school. Figure 2F shows that more than three-quarters of Victorian children were considered by their Prep teachers to have made a good transition to school.

Figure 2F

Victorian Prep teachers ratings of children's transitions to school in 2012

|

School transition indicators |

Often or very true (per cent) |

Sometimes or somewhat true (per cent) |

Never or not true (per cent) |

Don't know (per cent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Child is making good progress in adapting to the structure and learning environment of the school |

78.9 |

18.3 |

2.4 |

0.5 |

|

Child has parent(s)/caregiver(s) who are actively engaged with the school in supporting their child's learning |

77.5 |

16.5 |

5.2 |

0.7 |

|

Child is regularly read to/encouraged in their reading at home |

79.4 |

14.5 |

4.8 |

1.2 |

Note: Totals subject to rounding errors.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AEDC data provided by DET.

Academic readiness

The Australian Curriculum Victorian Essential Learning Standards (AusVELS) outline common statewide standards for children between Prep and Year 10 that schools use to plan learning programs, assess progress, and report to parents. Introduced in 2013, AusVELS replaced the previously used curriculum standards, the Victorian Essential Learning Standards (VELS). Each semester, school teachers at each year level assess each of their students against AusVELS.

In 2013 end of year data, only a very small percentage of children in Prep were rated as six months or more behind in English and mathematics—3 and 1 per cent respectively. Between 25 per cent, for English, and 20 per cent, for mathematics, of Prep children were at least six months above the level expected.

Photograph courtesy of bikeriderlondon/Shutterstock.com.

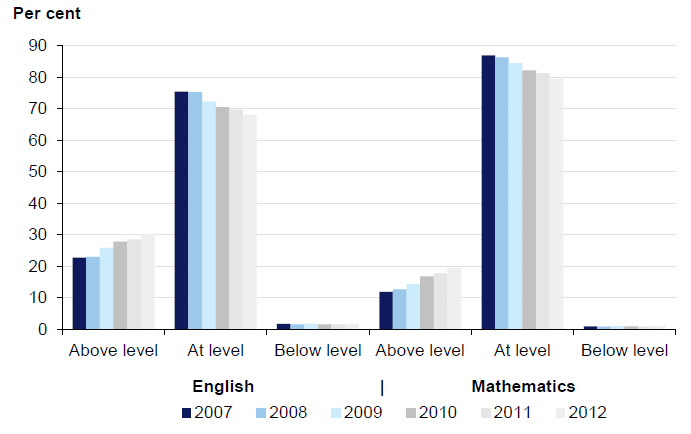

Since 2007, the proportion of children who were rated by their Prep teacher as above the expected level in both mathematics and English has risen, as seen in Figure 2G. Correspondingly, the proportion of children at the expected level has declined over the same period. There has been negligible change in the proportion of students below the expected level.

Figure 2G

Prep children, rated by teacher judgements, compared to their expected level for English and mathematics from 2007 to 2012

Note: This figure reports end-of-year data recorded in Semester 2.

Note: From 2013, teacher assessment data was collected against a revised standard, which is not comparable to past results.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office analysis of Victorian Essential Learning Standards data.

These outcomes suggest that the majority of children who transition to school are well prepared academically. They also highlight that there is a sizeable and growing minority—approximately 30 per cent in English and 20 per cent in mathematics—of children who start school considerably above the expected level.

2.4 Strengths in the current approach

There are a number of strengths in DET's current approach to early-years transitions. It has developed a well-researched, robust framework with clear guidance and resources for schools and early childhood education and care providers. In addition to targeted programs for vulnerable children, DET introduced transition statements that convey information from early childhood educators and families to Prep teachers. DET has also increased kindergarten participation rates to very high levels.

2.4.1 Attendance at high-quality kindergarten services

There is increasing international and Australian evidence that participation in a quality kindergarten program has a positive impact on children's developmental vulnerability as they enter school and on their later school outcomes. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's Education at a Glance report in 2013 concluded that this impact was present even when accounting for the socio‑economic background of the child. Using the Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research concluded that attendance at kindergarten added 10 to 15 points to a child's Year 3 National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy results, which is equivalent to 15 to 20 weeks of schooling.

Figure 2H shows the link between kindergarten attendance and the development of language and cognitive skills for children in their first year at school in Victoria.

Figure 2H

Association of attendance at kindergarten with language and cognitive development

|

Percentage of Prep children developmentally 'on track' |

|

|---|---|

|

Had attended kindergarten |

85.7 |

|

Had not attended kindergarten |

68.6 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AEDC data provided by DET.

This difference may reflect either the population likely to attend a kindergarten program or the benefits of the program itself. The Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research noted that children who do not attend kindergarten may be more disadvantaged and have parents who place less value on education, making it difficult to isolate the impact of kindergarten participation on later outcomes. After controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, the research concluded that children who did not attend kindergarten would have gained more from attending kindergarten than those who actually attended.

2.4.2 Sound and well-supported early-years framework

Sharing information—common framework

One of the ways to support successful transitions is to ensure that information gathered by one educator is shared with the next. In Victoria, all early childhood education and care professionals working with children from birth until the age of eight—which includes teachers working in schools—were brought under the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF) in 2009.

VEYLDF provided educators with a common language and set of outcomes, regardless of whether they worked in early childhood education and care setting such as kindergartens, or within schools with children in years Prep to Year 2. The framework brought together the Australian Early Years Learning Framework and the school-based VELS.

DET's Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative is an important element of VEYLDF. It aims to improve children's experience of starting school by enhancing the development and delivery of transition programs.

A key part of this initiative was the introduction of a standardised Transition Learning and Development Statement (transition statement) that early childhood educators and families complete to share information with the school about the child's learning and development. It also allows the early childhood educators to indicate to the school if they would like to speak with the child's Prep teacher about specific issues. This remains a good example of DET seeking to address a major transition issue.

The initiative is accompanied by a comprehensive resource kit for schools and early childhood education and care services that provides detailed information about effective programs and approaches to transition planning. It also includes advice about additional support for specific groups of children and families.

In 2009, DET changed the Victorian kindergarten policy, procedure and funding criteria to make completion of transition statements a requirement of funding. In 2013, providers of kindergarten programs reported completing a transition statement for 95.2 per cent of enrolled children. It is likely that linking the funding to the completion of the statements by kindergarten services has contributed to this high compliance rate. However, in 2013, only 80 per cent of children at government schools arrived with a completed transition statement. Of the 20 per cent of children who did not have a transition statement, half were then completed by the Prep teacher with the family. Multiple factors influenced this result, including parents not giving consent to transfer information and not advising where the child is transitioning to.

Comprehensive approach

DET has adopted a comprehensive three-tiered approach to supporting successful transitions in the early years:

- Universal—all children are expected to arrive at school with a transition statement containing information from early childhood educators and family that will assist in supporting a successful transition to school.

- Targeted—initiatives to support children who are part of a cohort known to be vulnerable to poor transition to school, such as Aboriginal children.

- Individual—initiatives to support children identified as being vulnerable to poor transition because of a disability.

Funded programs and resources for students with extra needs

DET allocated $367.5 million in 2013–14 to support students to prepare for and transition into school through support for regular kindergarten places and a range of special initiatives in the early years including:

- Early Childhood Intervention Services

- Kindergarten Inclusion Support Packages

- Early Start kindergarten.

Further, children who require additional support at school due to having disabilities and moderate to severe needs can be supported under the Program for Students with Disabilities (PSD) once they commence school. Currently government schools receive PSD funding to provide targeted support for 22 281 students (4 per cent). Two-thirds of applications for Prep students are made prior to or shortly after the start of the school year, by mid-February. This means that the majority of these students are identified as potentially needing assistance before they commence school.

2.5 Weaknesses in the current approach

Despite the strengths, there are some weaknesses in DET's approach to supporting early-years transitions. In particular:

- further work is required to target support towards the students identified as vulnerable in Figure 2E

- DET could make better use of available data

- there are persistent challenges for schools and early childhood services in how they communicate and understand continuity of learning between kindergarten and school.

2.5.1 Better targeting of vulnerable cohorts is needed

The current National Partnership Agreement on Universal Access to Early Childhood Education, agreed to by DET, has an explicit focus on improving participation in kindergarten programs for vulnerable and disadvantaged children. The agreement defines these as including, but not being limited to, children:

- from Aboriginal backgrounds

- with a disability

- being in, or at risk of being placed in, the child protection system

- in communities identified, through AEDC, as having significant vulnerabilities

- in low socio-economic communities

- who are refugees or children of refugees at risk

- from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Despite this and the fact that DET has met its overall kindergarten participation performance measure for the past four years, DET does not set or report on targets for increasing kindergarten participation in these high priority groups.

2.5.2 Inadequate collection and use of data

While DET has taken steps to improve data collection and the use of that data in relation to early-years transitions, there are a number of unresolved issues.

Lack of child-level outcomes and indicators

Currently in Victoria, once a child enters a government or non-government school they are given a unique student identifier called a Victorian Student Number (VSN). The VSN was introduced in 2011, and follows a child from Prep until they are aged 25 if they are enrolled in school or vocational education and training—but not in higher education. While currently linked to basic identification and enrolment information, it has the potential to allow for better tracking, and the linking of children's outcomes with a range of other data. This unique identifier does not exist in early childhood education.

As part of its Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative, DET commissioned research to develop and trial an evaluation tool to measure the outcomes and indicators of a successful transition to school for children, families and their educators. DET has not completed this work.

While DET has sought to use its mid-year supplementary school census to establish the value and use of the transition statements for Prep teachers, the data is of low quality and there is no evidence that the data collected is used to inform ongoing policy development in this area.

Through its Abilities Based Learning and Education Support curriculum resource, DET has made some progress on measuring outcomes for school students with disabilities. However, it remains unclear if this will enable DET to examine whether the funding allocated to support these students is being effectively used, or if the extensive policy and program work aimed at supporting these students during transitions has been effective.

Issues with kindergarten reporting and measures of quality

Care must be used when looking at kindergarten participation rates, as data on participation in kindergarten is fraught with difficulties. This situation is not just particular to Victoria.

Consistent with national data collection measures, the definition of attendance or participation in kindergarten used in reporting is that the child was enrolled and had attended the program for at least one hour during the reference period—the census week in August.

Audited early childhood education and care services and schools provided examples of children not attending kindergarten for periods of up to three months while visiting relatives from their home country, or having attendance impacted by a lack of transport, for example. Despite DET's reported local and statewide averages being much higher, one audited school reported that less than 50 per cent of students that enrolled in 2014 had attended a kindergarten. None of the publicly reported data on participation captures these variations.

Until 2014, DET calculated local kindergarten participation rates based on the postcode of the service, rather than the child's address. This contributed to inaccuracies in locally reported rates, including the situation that in 2013, 34 of 79 local government areas had participation rates of more than 100 per cent. DET has recently started to use the postcode of the child's address rather than the provider's address. It hopes this will produce more accurate data for planning and service delivery. In addition, DET has begun scoping for an Early Childhood Management Solution which aims to improve the identification and tracking of children in early childhood services. The scoping phase is due to be completed in late 2015.

2.5.3 Issues with information transfer

As mentioned earlier, transition statements are intended to help Prep teachers get a better understanding of the children coming into their classes. Most early childhood education and care providers comply with the requirement to supply these statements to government and non-government schools because their completion is linked to funding.

However, early childhood service providers visited for this audit reported that the transition statement took over an hour to complete for each child, not including the time needed to explain and receive feedback from parents. Many early childhood service providers also felt unsure about whether the transition statements, or indeed their own professional knowledge of the child, was valued by schools. This is not necessarily a reflection about the usefulness of the statements to transfer information, but is more about the communication and respect that exists between early childhood teachers and primary school teachers.

Most Prep teachers in audited schools stated that the transition statements were of limited use, as they did not provide a balanced picture of the skills of a child. In line with the research literature that informed the Transition: A Positive Start to School initiative, and the fact that parents must give permission for the transition statements to be sent to schools, kindergarten educators are instructed to write the statements based on the child's strengths, rather than deficits. This focus on 'strength-based' assessment was cited as a difficulty. Understandably, Prep teachers placed more value on being able to observe the child in an early childhood setting or during Prep orientation days. However, this does not mean that the statements are without value, particularly where observation of the child was not possible.

Despite the common framework developed under VEYLDF, staff in audited schools perceived a lack of consistency and congruity in what is taught in early childhood education and care services with what would set the foundation for a successful transition to school.

According to DET, the principal role of a kindergarten program is to engage each child in effective learning, thereby promoting communication, learning and thinking, and to develop in each child the capacity for positive relationships and a sense of identity. Notably, the majority of early childhood educators stated that they did not see their role as preparing children for school—rather they saw their role as helping children develop social and self-care skills.

Few educators in either early childhood or school-based settings had professional experience in the alternate settings. Educators who had this experience felt that they had a special insight that would ultimately help them provide a positive transition experience for children. This suggests that more training and professional development is required to bring educators in early childhood and school-based settings to a shared understanding of the roles of the two sectors.

Recommendations

That the Department of Education and Training:

- reviews all child-level and service-level data collected by it from maternal and child health services, and early childhood education and care providers in order to:

- ensure that the collected information is sufficient and appropriate for the Department of Education and Training to monitor the impact of these services on children's long-term educational outcomes

- develop reporting requirements to collect and record this information in a way that allows the Department of Education and Training to link child-level data collected prior to school with data collected after school enrolment

- reviews the use of early-years transition statements with a particular focus on:

- adequacy of the information captured

- relationships between early childhood and school-based educators

- training and development for educators in early childhood and school-based settings to develop a shared understanding of the role of both sectors

- develops and monitors transition-related outcomes for the early years including for children identified as most vulnerable during school transitions.

3 Middle-years transition

At a glance

Background

To transition successfully to secondary school, children need to be supported before, during and after the transition. Children who have difficulty with this transition are likely to become more disengaged and have poorer academic outcomes in the future.

Conclusion

Middle-years outcomes are mixed, with some encouraging trends in the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy results and parents' views on transitions. However, the Department of Education and Training (DET) does not provide enough support to schools to properly support students or improve their own practices. DET should monitor children's post-transition outcomes more effectively.

Findings

- In some measures, children's academic outcomes and engagement with school decline after transitioning to secondary school. Boys' performance declines faster than girls.

- Parents' ratings of school support for children, as they transition, have improved.

- Schools undertake a variety of informed practices to support transitioning children.

- DET has a role to manage inconsistencies across the system and to properly support schools to transition students effectively. It does not do either well.

- DET does not undertake system-level monitoring to track transition outcomes.

Recommendations

The Department of Education and Training:

- develops and monitors transition-related outcomes for the middle years, including for children identified as most vulnerable during school transitions

- develops a more comprehensive suite of guidance and resources to support schools to transition middle-years students

- improves its systems to allow more timely access to child-level data for schools

- examines the appropriateness of the timing of the Year 6 review for children who receive funding under the Program for Students with Disabilities.

3.1 Introduction

The transition into secondary school is a significant one for children and it occurs as children are undergoing the developmental changes associated with the onset of puberty. In moving to secondary school, children enter a new social world and move to a more independent learning environment. The shift often involves a change in the type of curriculum and pedagogy (teaching methods) from that experienced in primary school. There is wide recognition of a drop in children's achievement and engagement with school after they make this transition.

The challenge for schools is to sustain children's progress and motivation as they make this transition during Years 5 through 8. Making a successful transition from primary school to secondary school has an impact on both children's engagement with school and their later academic outcomes. International research suggests that children who fall behind at this point will find it increasingly difficult to make up the lost ground.

3.2 Conclusion

There have been modest improvements in some middle-years transition outcomes over the past seven years. However, there are well established gender-based differences in both academic and engagement outcomes during the middle years that the Department of Education and Training (DET) has not addressed.

The static nature of middle-years outcomes over time suggests that there is room to improve the approach to managing this transition. However, DET has not done enough to fully examine the trends in the data and relate this back to the strategies and approaches being employed by schools to transition students.

Unlike the early-years transition, DET does not have a clear strategy or framework guiding the middle-years transition. It does not require a transition statement to be prepared and shared with secondary schools. As a result, schools are tackling middle-years transitions in varying ways and while this has resulted in some innovative practices, it has also lead to inefficiencies across the school system.

Given the lack of guidance and support from DET, the modest improvements in middle-years transition performance can only be attributed to the schools themselves tailoring their delivery of education to their students.

System-wide change is required if consistent long-term gains are to be made, and if issues such as the uneven impact of transitions on male and female students are to be resolved. There are simple steps that DET could take to better support schools to improve middle-years transitions, including evaluating the available data more thoroughly to inform targeted strategies and initiatives to support vulnerable students, and drawing on the successful approaches already in place for early-years transitions.

3.3 Middle-years outcomes

For children transitioning between primary and secondary school, a range of academic and wellbeing-related data is available. This section examines:

- academic performance

- children's engagement with school

- parents' assessment of children's transitions.

3.3.1 Academic performance

There are a number of ways in which the academic performance of school students is measured and monitored:

- The Australian Curriculum/Victorian Essential Learning Standards (AusVELS)outline statewide standards for students between Prep and Year10 that schools use to plan learning programs, assess progress and report to parents. Every semester teachers assess each of their students against the relevant AusVELS standard. These replaced the Victorian Essential Learning Standards (VELS), which were in place until 2012.

- The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN)is used to assess the performance of Australian children against a national minimum standard for numeracy and reading and writing. Children are tested at Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. The Year 5 and 7 assessments fall either side of the middle‑years transition and provide a good measure of their transition outcomes.

Teacher assessments of student performance against AusVELS

Teacher assessments against AusVELS show that the percentage of children whose performance is below the expected level increases as each child progresses through school, as shown in Figure 3A. Despite this fairly linear change, there are some notable variations:

- Year 6 results immediately prior to transition show a lull in the trend, particularly for English, with less of an increase in the number of children who are below the expected level.

- Year 7 results immediately following the transition reverse the Year 6 gain, and is then followed by a pattern of declining performance from Year 8 to Year10.

Improving the middle-years transition process could assist in achieving significant improvements to student outcomes in Year 7 and beyond.

Figure 3A

Percentage of children in 2013 assessed as being six months or more below the expected levels in English and mathematics

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on AusVELS 2013 data, provided by DET.

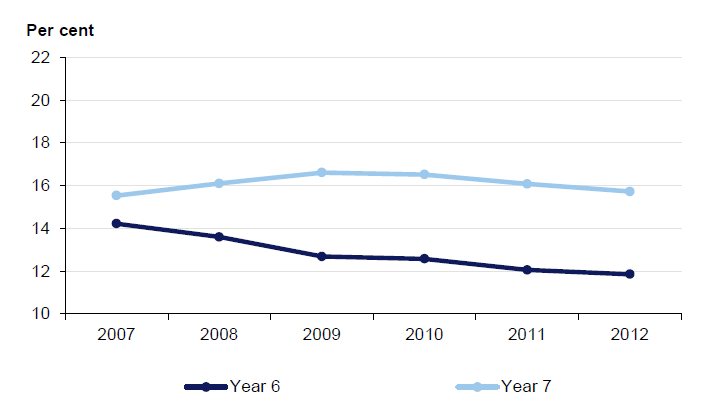

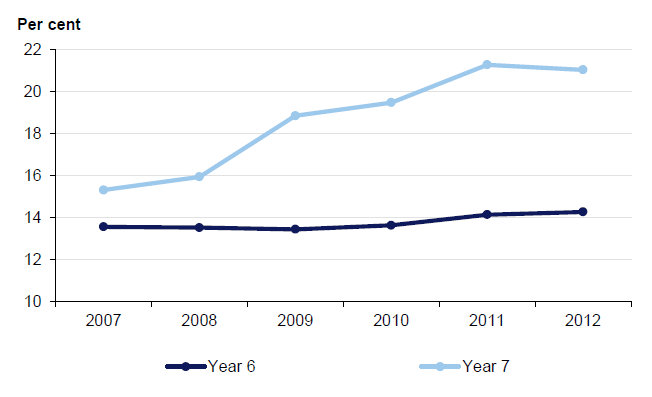

Figures 3B and 3C show the gap in outcomes between Year 6 and Year 7, from 2007 to 2012, in both English and mathematics. In both charts, a downward trend indicates a positive outcome.

In both English and mathematics, the gap between Year 6 and Year 7 performance has increased.

In English, teachers of Year 6 students were more positive about the capabilities of their students, while teachers of Year 7 students maintained their position.

In mathematics, teachers of Year 6 students have held a consistent view of student performance over time. However, the proportion of Year 7 students assessed as below the expected standard rose significantly from 15.3 per cent to 21.1 per cent over the five years.

Figure 3B

Students assessed as being six months or more below the expected level in English

Note: From 2013, teacher assessment data was collected against a revised standard, which is not comparable to past results.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VELS data, provided by DET.

Figure 3C

Students assessed as being six months or more below the expected level in mathematics

Note: From 2013, teacher assessment data was collected against a revised standard, which is not comparable to past results.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on VELS data, provided by DET.

Student performance in NAPLAN