State Purchase Contracts

Overview

The Victorian public sector (VPS) buys a lot of goods and services—$18.6 billion worth in 2016–17. One way that this purchasing power is harnessed is through State Purchase Contracts (SPC), which aggregate demand for commonly used goods and services such as utilities, office consumables, staffing services, information and communication technology (ICT) services and travel services.

In this audit, we assessed whether government agencies realise financial and other benefits through their use of SPC. We focussed the effectiveness of oversight of SPC by VGPB and lead agencies. We also examined whether reported benefits are reliable, and to this end considered also whether there is scope to increase the financial benefits obtained from these arrangements.

We made:

- one recommendation to VGPB to address the central collection of comprehensive procurement data

- five recommendations to lead agencies DTF, DPC and DJR to address how they manage SPCs as well as how they set, monitor and report on benefits

- two recommendations to DTF and DPC address the need to assess user satisfaction with SPC and centrally record applications for exemptions

- three recommendations for all departments as SPC users to address the need to understand and monitor contract leakage and centrally record applications for SPC exemptions.

Transmittal Letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER September 2018

PP No 441, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report State Purchase Contracts.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

20 September 2018

Acronyms and abbreviations

|

ANZSIC |

Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification |

|

ASR |

Annual Supply Report |

|

CAFAS |

Commercial and Financial Advisory Services |

|

CMP |

Category Management Plan |

|

DEDJTR |

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

|

DELWP |

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

|

DET |

Department of Education and Training |

|

DHHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

DJR |

Department of Justice and Regulation |

|

DPC |

Department of Premier and Cabinet |

|

DTF |

Department of Treasury and Finance |

|

FMA |

Financial Management Act 1994 |

|

ICT |

information and communication technology |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

NSW |

New South Wales |

|

PAS |

Professional Advisory Services |

|

SPC |

State Purchase Contract |

|

VAGO |

Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

|

VGPB |

Victorian Government Purchasing Board |

|

VPS |

Victorian public sector |

|

VPS 5 |

Victorian Public Service Grade 5 |

|

WA |

Western Australia |

Audit overview

The Victorian public sector (VPS) buys a lot of goods and services—$18.6 billion worth in 2016–17. One way that this purchasing power is harnessed is through State Purchase Contracts (SPC). SPCs aggregate demand for commonly used goods and services such as utilities, office consumables, information and communication technology (ICT), staffing and travel services.

The primary benefit of an SPC is financial—that is, government achieves direct savings through lower unit costs and prices than would be possible through fragmented VPS procurement. Other benefits include reduced transaction costs for suppliers and buyers, as well as the ability to influence and improve the quality of service offerings.

In 2016–17 the Victorian Government's 34 SPCs had a combined annual spend of approximately $1.47 billion, growing from $1.06 billion in 2014–15.

The Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB) is responsible for monitoring the compliance of departments and specified entities with VGPB supply policies. The Market analysis and review policy includes the requirement for these agencies to use mandated SPCs and outlines the process that lead agencies must follow to establish an SPC. Four lead agencies manage SPCs—primarily the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF ), but also the Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR) and Cenitex. Each SPC can involve either a sole supplier or a panel arrangement. The typical term for an SPC is three years with provision for two one-year extensions. During the term, the panel may be open, admitting new suppliers, or closed.

Of the 34 SPCs, 23 are mandatory for use by all 34 agencies subject to VGPB policies, with the remaining being optional. Statutory authorities, local councils, organisations that government partly funds, and charitable or not‑for‑profit organisations can use SPCs voluntarily, subject to approval from lead agencies.

VGPB reports to the Minister for Finance, with DTF providing it with secretariat and other support. VGPB was established in 1995 under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) to:

- develop, implement and review supply policies and practices

- monitor compliance with supply policies

- develop procurement capability

- establish and maintain a comprehensive database of departments' and supply markets' purchasing data, for access by departments

- provide strategic oversight of major procurements

- engage with stakeholders to drive greater procurement efficiencies.

Our overall objective for this audit was to assess whether government agencies realise financial and other benefits by using SPCs.

We examined whether VGPB and lead agencies oversee SPCs effectively. We also examined whether the reported benefits are reliable and whether scope exists to increase the financial benefits of these arrangements.

Conclusion

SPCs provide financial savings and other benefits. However, more savings are possible if contract management activities are strengthened to better manage suppliers, reduce the risk of leakage—expenditure made outside of mandatory SPCs—and aggregate spending in new categories. The VPS cannot fully realise these savings without comprehensive and detailed spend data, and it is the absence of such centralised data that VGPB must address .

Financial management reform in the public sector over the past three decades has included decentralised budgeting, accounting and reporting. This has led to the siloed information systems that feature today in Victorian Government departments. Departments need to harness today's technology to redress this, not just to secure better data for procurement but to make public sector financial management broadly more efficient.

Findings

Informing procurement

Neither VGPB nor lead agencies have a complete picture of the goods and services VPS agencies purchase. This is mainly due to the absence of standardised systems and consistent business rules that govern how purchasers collect and classify information.

As a result, VGPB and lead agencies do not know, who is buying what, from which suppliers and at what cost. Instead, they rely on suppliers to self-report . This means they have limited insight into potential contract leakage, and they do not fully understand all the categories of expenditure that could possibly be aggregated.

Aggregation

Lead agencies undertake market analysis and consult with key stakeholders including representatives from SPC users to support category strategy development. However, VGPB and lead agencies lack consolidated, detailed transaction data, so they are not well equipped to conduct meaningful and insightful spend analysis to develop category strategies. Because they use supplier-reported data on existing SPCs, their category strategies relate only to these existing SPCs rather than entire expenditure categories. This results in potential missed opportunities to realise further benefits.

Lead agencies undertake ad hoc checks of the supplier-reported data and require SPC users to confirm spend for some SPCs, but their verification activities are limited because they do not have all the information needed to sufficiently assess and validate the supplier reports.

We obtained and consolidated the past three years' worth of expenditure data from the seven Victorian Government departments. Our analysis of the 2016–17 year highlights the following areas of common goods and services expenditure for which SPCs do not currently exist:

- accounting services—of the $37.1 million total departmental spend in 2016–17, the top two suppliers account for 94 per cent

- market analysis and statistical services—of the $13.4 million total departmental spend in 2016–17, the top five suppliers account for 52 per cent.

Leakage

User departments and agencies are responsible for ensuring that expenditure made outside of mandatory SPCs, or 'leakage' does not occur. However, they do not understand or manage contract leakage in their organisations.

Lead agencies also do not effectively oversee user departments' compliance with mandatory SPCs.

We examined expenditure data at the seven departments to identify potential leakage in four mandatory SPCs. In a significant number of transactions, we were unable to determine the nature of the spend due to the limited descriptions on the invoices. Given these limitations, our analysis is conservative and indicative—it uses the best available data in departments' finance systems .

Our analysis for 2016–17 shows potential leakage of:

- $0.25 million, or 2.1 per cent of the total spend of $12.23 million, in the stationery category

- $0.06 million, or 0.1 per cent of the total spend of $48.64 million, in the travel category

- $2.07 million, or 0.7 per cent of the total spend of $289.37 million, in the staffing category

- we found no potential leakage in the legal services category.

This leakage, if confirmed, would contradict the statements of compliance made by departments in their Annual Supply Reports (ASR) to VGPB.

Managing contracts

VGPB oversight of SPCs

VGPB does not have the resources to directly oversee the management of all SPCs or ensure compliance with its supply policies. With its limited resources it sensibly monitors only the compliance of the seven departments, Public Transport Victoria, VicRoads, Victoria Police and Cenitex, as opposed to all 34 VPS agencies in its scope.

|

Annual Supply Reports The seven departments, Public Transport Victoria, VicRoads, Victoria Police and Cenitex each submit an ASR to VGPB each year. The ASRs summarise procurement activity and report instances of non‑compliance with VGPB policies, including the use of mandatory SPCs. |

VGPB acknowledges the limitations of its monitoring activities in assessing compliance with its policies. For example, in their 2016–17 ASRs to VGPB, the seven departments raised no compliance issues with their SPC obligations. This is despite being unable to tell us whether contract leakage was occurring. However, VGPB accepted these assertions without detailed scrutiny or auditing of the information. VGPB stated that this was due to the lack of data and the tight time frame specified in the FMA between entities submitting their ASRs and VGPB including them as part of its annual report.

While VGPB's audit program requires entities to verify compliance with mandatory policy requirements and submit a report to VGPB every three years, this verification takes place well after assertions are made.

VGPB oversees the establishment of SPCs, however, its oversight of lead agencies' contract management activities is minimal once the contract is executed. While VGPB requests an update from lead agencies at certain milestones, these milestones are at the one- or two‑year points of contracts that run for three years.

Lead agencies' management of SPCs

Lead agencies use contract management frameworks to manage SPCs. However, there are inconsistent management practices across the four lead agencies.

There is an opportunity to improve SPC performance by better monitoring suppliers' performance and sharing information with users, including:

- assessing client satisfaction

- managing key suppliers

- sharing savings opportunities with departments and entities

- tracking SPC prices.

Assessing client satisfaction

DTF surveys SPC users annually to assess their satisfaction with SPCs. The 2016−17 results indicate that almost three-quarters of users were satisfied with their overall experiences. Although this survey is useful, it does not show users' assessments of suppliers on individual engagements. This is particularly important for panel supplier arrangements such as the Professional Advisory Services (PAS) SPC, where DTF could use this information to address performance issues and notify users of issues with specific suppliers.

While the PAS SPC requires users to complete a satisfaction survey and forward it to DTF at the completion of each engagement, only a limited number of users do so. Consequently, as it acknowledges in the PAS category strategy, DTF has little visibility of the SPC's performance and buyer satisfaction.

In 2016–17, DJR undertook an extensive consultation process on the Legal Services Panel SPC to develop a new client satisfaction survey. The survey results feed into annual performance review meetings with suppliers. The survey results indicate that users are generally satisfied with the services provided by the panel.

DPC and Cenitex have limited visibility of users' assessments of supplier performance because they do not survey SPC users.

Managing key suppliers

The establishment of an SPC concentrates government expenditure with a select number of suppliers. Eight of the top 10 suppliers to the seven departments were SPC suppliers.

To manage an SPC well, lead agencies need to understand the level of supplier spend and to use this information to leverage further savings. However, this is not always occurring. For example, DPC's June 2018 review into labour hire and professional services found that despite the significant expenditure on PAS to a limited number of suppliers, 'there is no active account management of these suppliers at the whole of government level and the aggregation of demand is not actively used to drive better pricing outcomes'. DTF advised it is in the process of developing a strategy for the future PAS SPC, focusing on more active central category management.

Sharing savings opportunities with departments and entities

Lead agencies share high-level information on departmental spend and usage with VGPB and stakeholders on an ongoing basis. However, scope exists to better communicate and highlight saving opportunities and trends across users because, presently, users have no transparent way to assess if they are receiving competitive rates from suppliers compared to other users.

Such information can be useful for the users of SPCs, where suppliers may charge different users varying rates for equivalent goods or services. For example, our analysis of the hourly rate achieved by four departments for 58 engagements of temporary Victorian Public Service Grade 5 (VPS 5) senior policy officers through the Staffing Services SPC in 2016–17, revealed significant variation in rates within and between departments.

As the lead agency, DTF should review and distribute such information to SPC users to help them achieve the same level of savings as other users. Our analysis also highlights the need for user departments to do more work to understand where different parts of their businesses are paying varying rates for the same service. Understanding internal spending patterns will help SPC users negotiate lower prices during future engagements.

Tracking SPC prices

The SPC user is primarily responsible for ensuring that the prices it pays accord with the SPC contract. However, purchasing decisions are made in user departments by different business units and are not all centrally tracked through their Internal Procurement Units . This hinders the ability of SPC users to monitor compliance with SPC pricing. DPC's June 2018 review into labour hire and professional services raised concerns with how departments check the compliance of invoices with agreed rates on the Staffing Services SPC and ceiling rates on the PAS SPC.

Lead agencies, as contract managers, should also conduct spot-check analyses of supplier-reported invoices for high-risk SPCs to ensure pricing validity and accuracy, including ensuring ceiling rates are not exceeded. However, they have not done so for all SPCs.

Measuring SPC benefits

The reported benefits calculated by lead agencies show significant savings by using SPCs. Reported savings ranged from $192 million in 2014–15 to $272 million in 2016–17. However, we found:

- six DPC-managed SPCs where the methodology for calculating savings resulted in the overstatement of benefits

- errors in spreadsheets used by DTF and DPC to track spend and benefits for SPCs

- seven SPCs, with a total spend in 2016–17 of more than $176 million, where lead agencies did not track financial benefits

- no documentation that reported the achievement of the non-financial benefits identified in many SPC business cases developed by DTF and DPC.

Targets

DTF is required to meet a financial-benefit performance target specified in the State Budget papers—'Benefits delivered as a percentage of expenditure by mandated agencies under DTF managed SPCs'. Between 2013–14 and 2016–17 DTF reported that it exceeded the target each year.

DTF advised that the target of 5 per cent was derived in 2013 from past performance data. However, it is unclear whether this is a reasonable measure against which to judge performance, because DTF has not documented the basis for the target. There is also no documentation that outlines how each of DTF's 17 SPCs contributes to the overall target. Further, the target has not changed over the four years, despite changes to market conditions and SPCs across this period.

While DTF identifies the expected financial benefit following the sourcing process for each SPC, there is scope to enhance this process by 'locking in' these financial benefits as targets. The next step for DTF would then be to measure reported financial benefits against these targets for each SPC.

DJR has a documented financial benefit target for the Legal Services Panel, which, since the panel's establishment in March 2016, it has consistently exceeded.

DPC and Cenitex do not have overall or individual SPC performance targets, which means they cannot demonstrate that their SPCs deliver the expected financial benefits, and therefore cannot demonstrate that their SPCs are performing well.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Victorian Government Purchasing Board:

1. in collaboration with portfolio departments and key State Purchase Contract users, develop and implement a strategy for the central collection of comprehensive procurement data across these agencies, that identifies:

- the procurement data that agencies need to record, as well as common rules around data entry through a common chart of accounts, to consistently capture and code goods and services expenditure

- how procurement data should be categorised, and includes a universally recognised categorisation approach such as the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification or the United Nations Standard Products and Services Code

- the cost benefit of options for developing a centralised system to collect and analyse procurement data from agencies

- how the Victorian Government Purchasing Board will share this data across agencies to improve decision making and identify potential new State Purchase Contract opportunities

- roles and responsibilities for the project and a time line for completion (see Section 2.2).

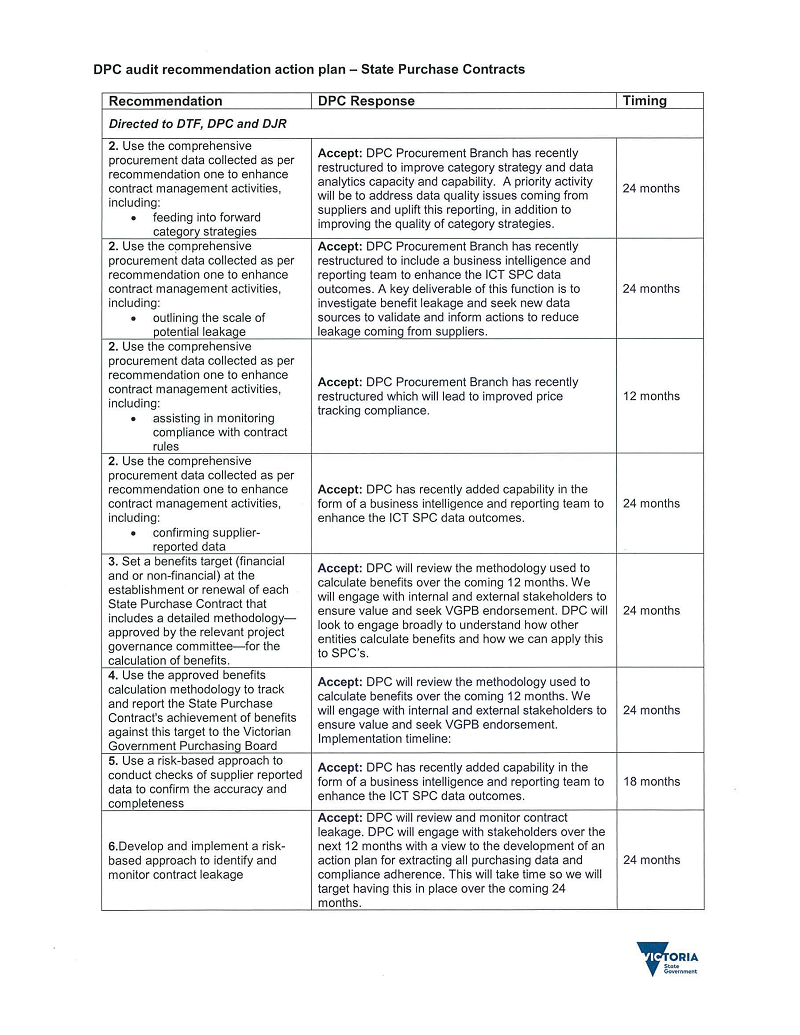

We recommend that the lead agencies Department of Treasury and Finance, Department of Premier and Cabinet and Department of Justice and Regulation in collaboration with portfolio departments and key State Purchase Contract users:

2. use the comprehensive procurement data collected as per recommendation one to enhance contract management activities, including:

- feeding into forward category strategies (see Section 2.2)

- outlining the scale of potential leakage (see Section 5.2)

- assisting in monitoring compliance with contract rules (see Section 3.3)

- confirming supplier-reported data (see Section 4.6)

3. set a benefits target (financial and or non-financial) at the establishment or renewal of each State Purchase Contract that includes a detailed methodology—approved by the relevant project governance committee—for the calculation of benefits (see Sections 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4)

4. use the approved benefits calculation methodology to track and report the State Purchase Contract's achievement of benefits against this target to the Victorian Government Purchasing Board (see Sections 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4)

5. use a risk-based approach to conduct checks of supplier reported data to confirm the accuracy and completeness (see Section 4.6)

6. develop and implement a risk-based approach to identify and monitor contract leakage (see Section 5.2).

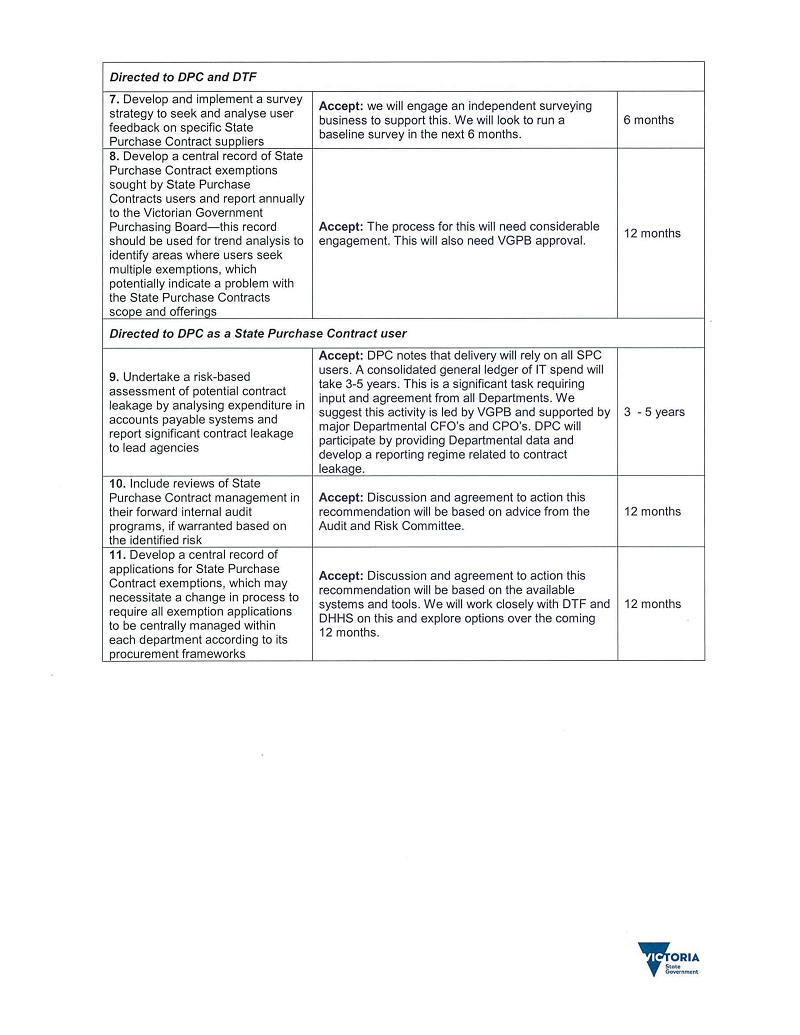

We recommend that the lead agencies Department of Treasury and Finance and Department of Premier and Cabinet:

7. develop and implement a survey strategy to seek and analyse user feedback on specific State Purchase Contract suppliers and engagements—this strategy should use a risk-based approach to identify:

- State Purchase Contracts that would benefit from analysis of user feedback

- the frequency of these surveys (see Section 3.3)

8. develop a central record of State Purchase Contract exemptions sought by State Purchase Contracts users and report annually to the Victorian Government Purchasing Board—this record should be used for trend analysis to identify areas where users seek multiple exemptions, which potentially indicates a problem with the State Purchase Contracts scope and offerings (see Section 5.4).

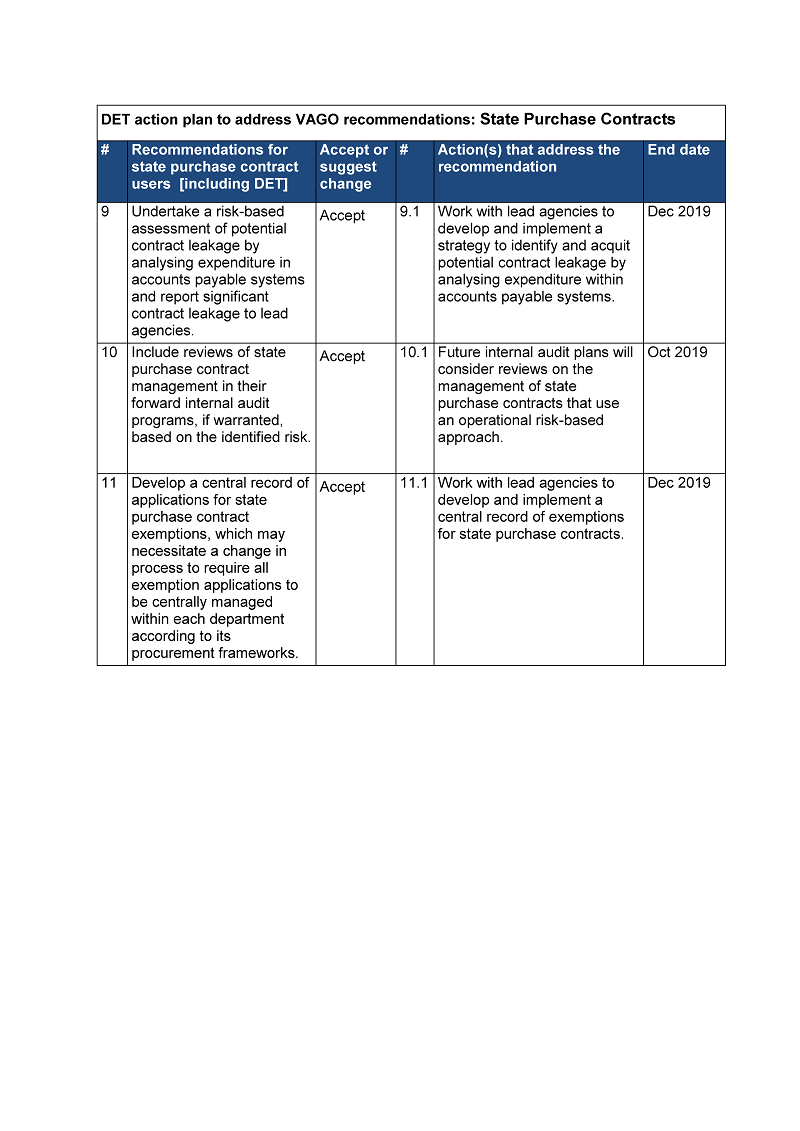

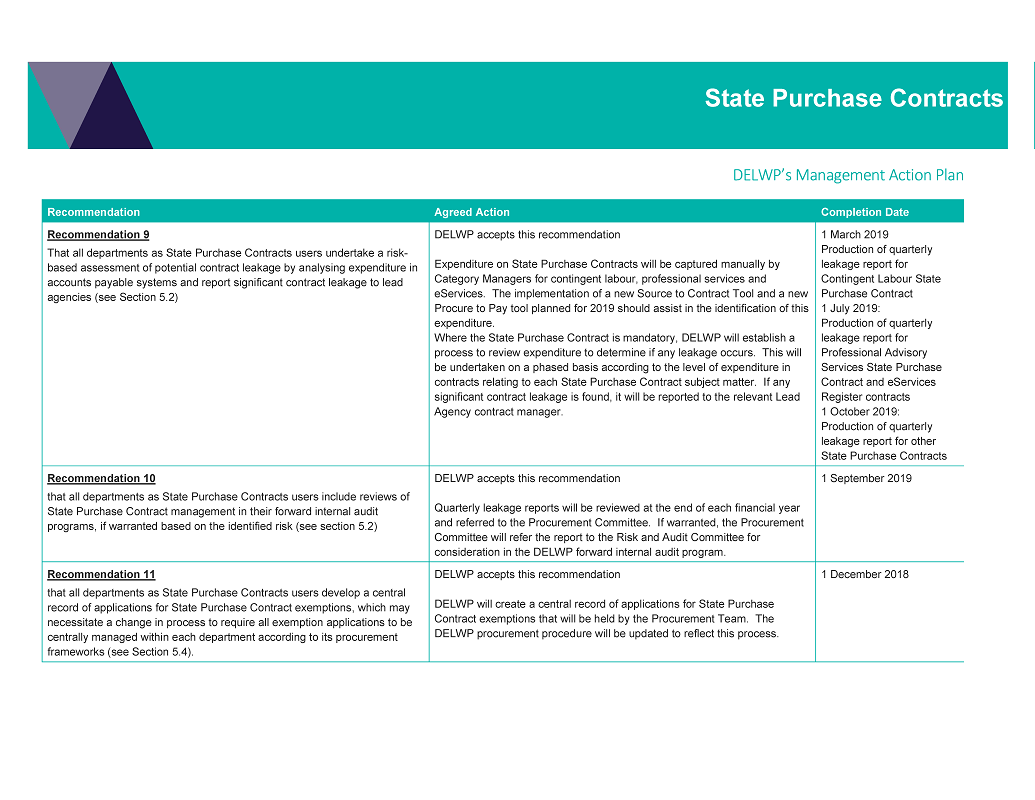

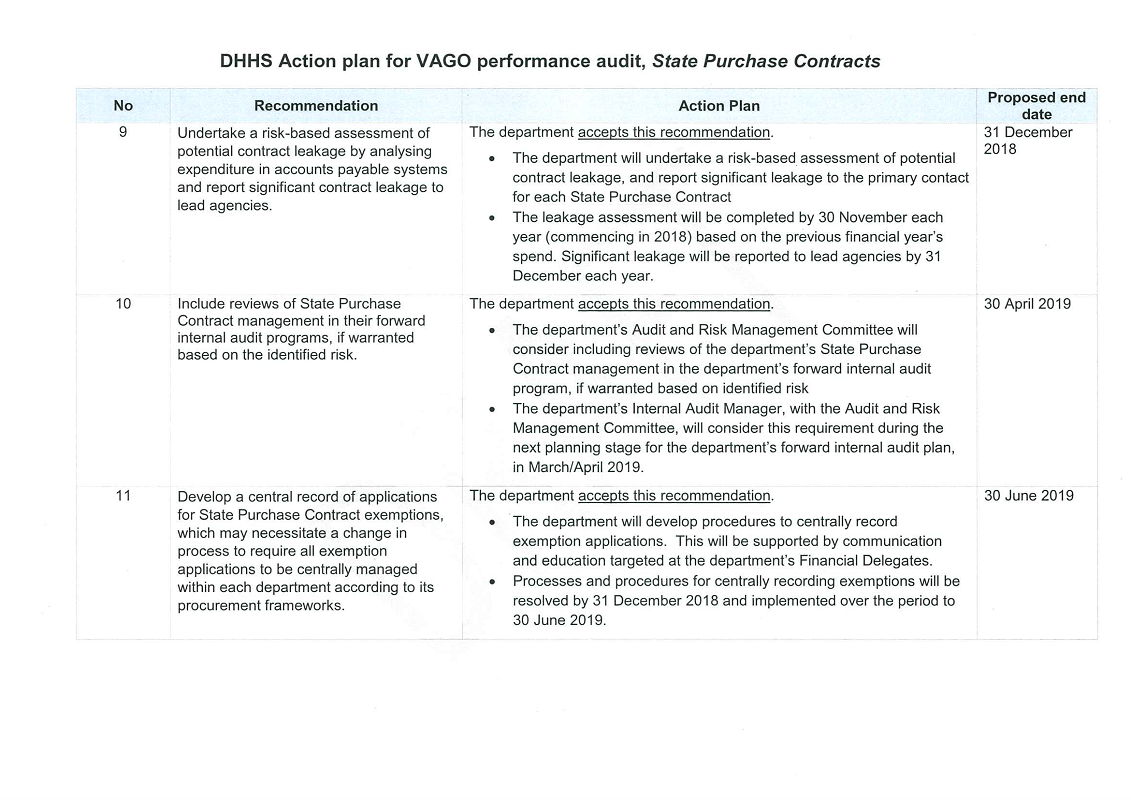

We recommend that all departments as State Purchase Contract users:

9. undertake a risk-based assessment of potential contract leakage by analysing expenditure in accounts payable systems and report significant contract leakage to lead agencies (see Section 5.2)

10. include reviews of State Purchase Contract management in their forward internal audit programs, if warranted, based on the identified risk (see Section 5.2)

11. develop a central record of applications for State Purchase Contract exemptions, which may necessitate a change in process to require all exemption applications to be centrally managed within each department according to its procurement frameworks (see Section 5.4).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with Cenitex, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR), the Department of Education and Training (DET), the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), DJR, DPC, DTF and VGPB, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

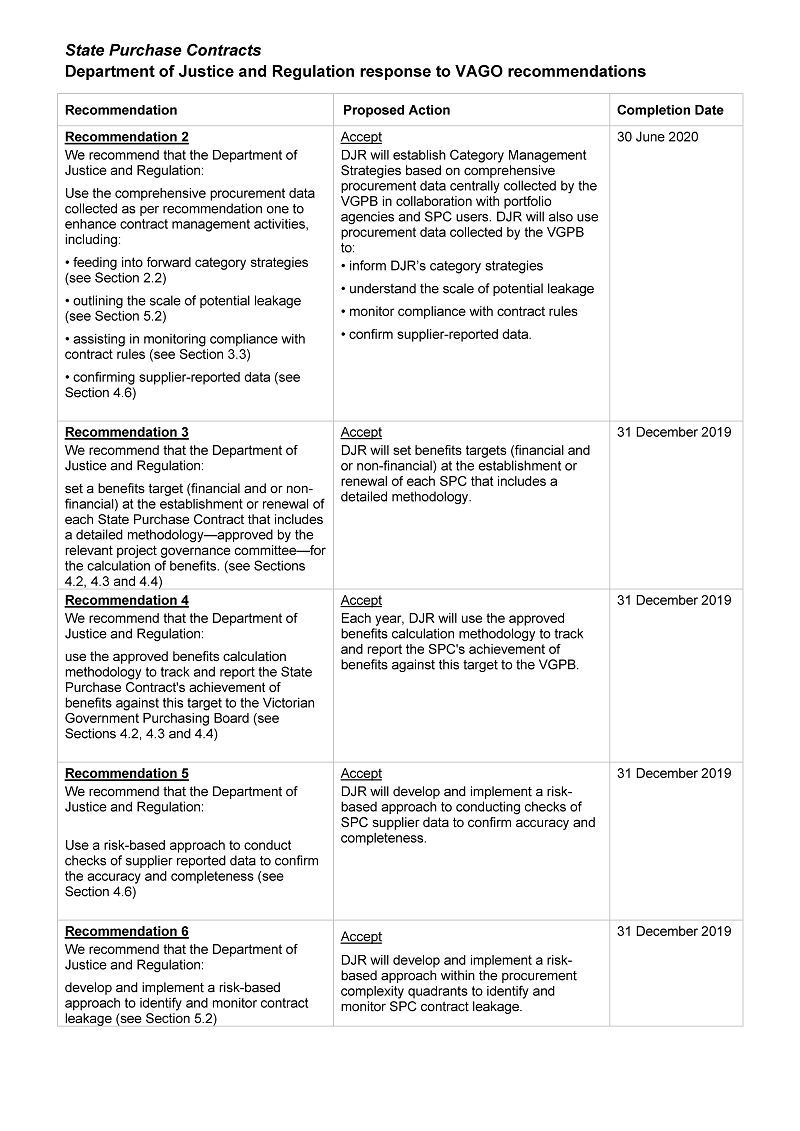

DPC and DJR accept all our recommendations as both lead agencies and users of SPCs and developed action plans to address them.

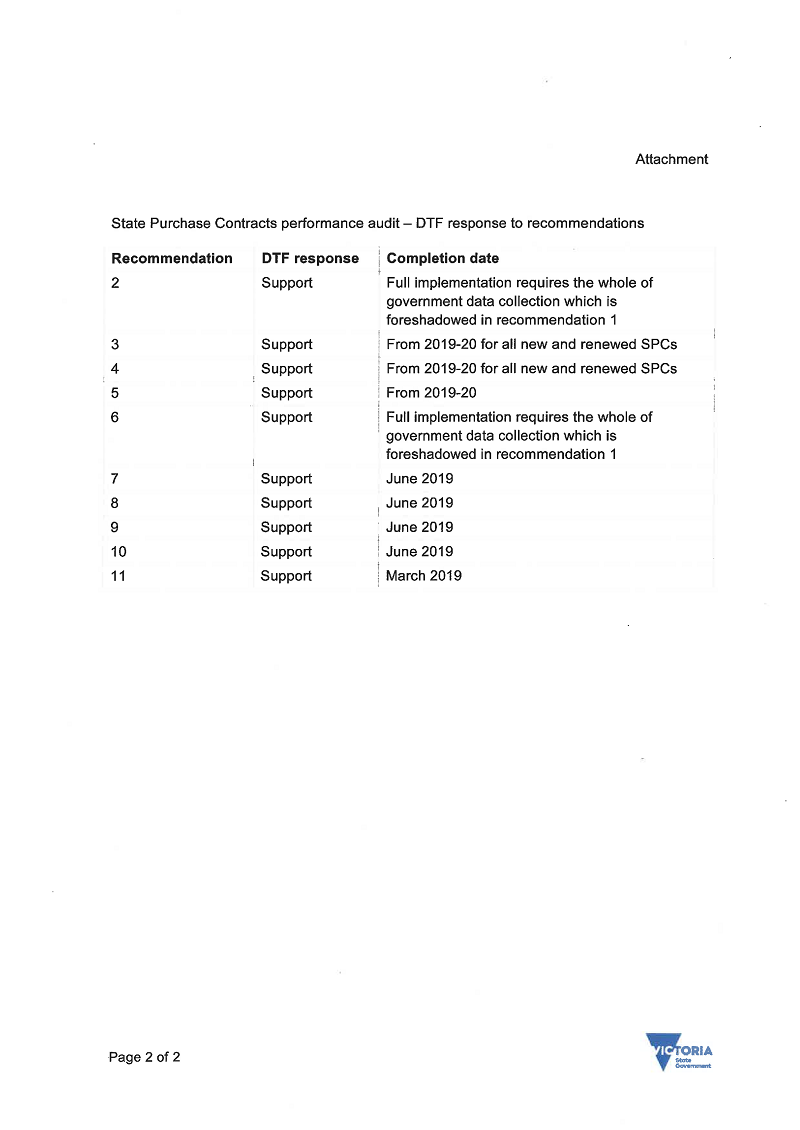

DTF supports all our recommendations as both lead agencies and users of SPCs and developed an implementation timetable.

DHHS, DET and DELWP accept all our recommendations as users of SPCs and developed action plans to address them.

DEDJTR accept our findings and will work with DTF and other lead agencies to implement the recommendations.

VGPB supports our recommendation to work with portfolio departments and key SPC users to develop and implement an e-procurement strategy for the central collection of comprehensive procurement data. This work has commenced as part of our procurement reform program and involves exploring solutions such as standard categorisation and consistent data capture.

Cenitex supports the report's findings.

1 Audit context

VPS is a major purchaser of goods and services. Spending on goods and services is typically the largest item of agency expenditure after employee costs. As Figure 1A shows, the value of VPS expenditure on goods and services reported in the 2016–17 Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria was $18.6 billion for the year.

Figure 1A

Overview of Victorian Government operating expenditure, 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on the Victorian Government's 2016–17 Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria.

1.1 Departmental goods and services expenditure

VPS has seven government departments:

- DEDJTR

- DET

- DELWP

- DHHS

- DJR

- DPC

- DTF.

In 2016–17 these departments accounted for $3.3 billion (17.7 per cent) of the total VPS goods and services expenditure.

Given this level of expenditure, the public sector has many opportunities to use its combined demand for common-use goods and services to achieve better value for money. This can be achieved through SPCs, which aim to:

- achieve lower prices by aggregating demand for commonly used goods, such as utilities, office consumables and ICT, and services such as staffing, and travel

- improve efficiency by reducing duplication of process.

1.2 Victorian public sector procurement framework

Various legislation governs the VPS procurement framework, described in Figure 1B, and the responsibility for policy advice, tools and training rests with several entities.

Figure 1B

VPS procurement framework

|

Entities |

Authorising legislation |

Entity responsible for policy advice, tools, training |

|---|---|---|

|

Goods and services |

||

|

FMA |

VGPB |

|

Other non-health entities |

Various |

Portfolio department or agency |

|

Health entities |

Health Services Act 1988 |

DHHS, Health Purchasing Victoria |

|

Construction |

||

|

All entities |

Project Development and Construction Management Act 1994 |

DTF |

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by DTF.

Victorian Government Purchasing Board

In 1995 VGPB was established under the FMA to:

- develop, implement and review supply policies and practices

- monitor compliance with supply policies

- develop procurement capability

- establish and maintain a comprehensive database of departments' and supply markets' purchasing data, for access by departments

- provide strategic oversight of major procurements

- engage with stakeholders to drive greater procurement efficiencies.

In February 2017 the government gave approval in principle to draft a Bill to amend the FMA and other legislation. The Financial Management and Constitution Acts Amendment Bill 2017 was introduced into Parliament in November 2017 and intends to update VGPB powers, functions and responsibilities.

VGPB's vision is to provide leadership in government procurement of goods and services, in order to deliver value-for-money outcomes for Victoria. Figure 1C depicts VGPB's strategic priorities for 2016–21.

Figure 1C

VGPB's strategic priorities, 2016–21

Source: Victorian Government Purchasing Board Strategic Plan 2016–2021.

The five-year strategic plan incorporates a priority for multi-organisation purchasing, which includes SPCs and other procurement models.

VGPB policies relate to the procurement of goods and services only, and apply to the following mandated VPS entities:

- all seven government departments

- VicRoads, Public Transport Victoria, Cenitex

- the Victorian Public Sector Commission

- 23 administrative offices or bodies specified in section 16(1) of the Public Administration Act 2004.

Appendix B shows the entities bound by VGPB policies.

VGPB policy does not apply to non-mandated public sector entities, local government, the procurement of building and construction works and services, or to health-related goods, services and equipment, as shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

VGPB's sphere of influence across the public sector

Source: VAGO , based on information provided by DTF.

VGPB works to improve procurement practices for the broader VPS and publishes accessible better practice guidance for all entities regardless of whether they are mandated to comply with VGPB policies or not. VGPB also works with non-mandated entities that want to bring their goods and services spend within the VGPB scope.

VGPB is developing a program to broaden the number of mandated public sector bodies and specified entities that it covers.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

Victorian Government Purchasing Board

VGPB reports to the Minister for Finance, with DTF providing secretariat and other support. The secretariat is also the conduit for communications between VGPB and departments through procurement forums, the dissemination of relevant procurement information on VGPB's website, and by email to the network of procurement personnel across government.

VGPB receives no direct funding and is instead resourced through DTF's allocation to the secretariat.

In April 2018 the Minister for Finance approved a VGPB request to change its oversight process to a more pro-active, engagement model. This approval recognised the increased procurement capability and governance processes of each department and stakeholder feedback from chief procurement officers.

The changes to VGPB oversight role are intended to drive delivery of the government's procurement reforms and to implement the recommendations of a procurement review undertaken by DPC in conjunction with DTF in December 2017 .

SPC lead agencies

A lead agency is responsible for establishing and managing each SPC. The VGPB Market analysis and review policy specifies that an entity that seeks to establish an SPC must:

- consult VGPB regarding the category of goods or services proposed for aggregation and inform VGPB of any analysis of spend or assessment of complexity that indicates grounds for aggregating demand

- have a business case endorsed by VGPB prior to submitting it to the relevant minister for approval

- demonstrate to VGPB that it has the capability to establish and manage the proposed SPC as the lead agency.

Once the lead agency obtains ministerial approval, it must again notify VGPB.

The VGPB Market analysis and review policy requires SPC lead agencies to:

- consider any comments made by VGPB and the relevant minister prior to engaging with the market

- inform VGPB and the relevant minister of the outcome of the market engagement process

- authorise an SPC head agreement setting out the key terms of a proposed agreement between parties on behalf of the Victorian Government.

Figure 1E shows the lead agencies for the 34 SPCs.

Figure 1E

SPC lead agencies

Source: VAGO.

DPC is the lead agency for SPCs relating to ICT, including hardware, infrastructure, telecommunications and software. DJR is the lead agency for the Legal Services Panel SPC. Cenitex is the lead agency for the Rosetta SPC, which relates to identity management and security software. Cenitex advised that the Rosetta SPC will likely terminate during 2018–19 given the government's intent to go to the market for a new identity and access management solution. DTF is the lead agency for SPCs relating to a selection of other goods and services.

1.4 State Purchase Contracts

The value of SPCs is significant and growing. Figure 1F shows that reported spend under SPCs increased from $1.06 billion in 2014–15 to approximately $1.47 billion in 2016–17. This is an increase of 38.7 per cent and accounts for around 8 per cent of total public sector expenditure on goods and service in 2016–17.

Figure 1F

Reported SPC spend by lead agency, 2014–15 to 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR and Cenitex.

SPCs are either mandatory or non-mandatory—based on an assessment by the lead agency—for entities bound by VGPB policies. Unless the lead agency grants a formal exemption, these entities must purchase from mandatory SPCs.

Statutory authorities, local councils, organisations that government partly funds, and charitable or not-for-profit organisations can use SPCs voluntarily, subject to approval from lead agencies. Where the lead agency grants access to a non‑mandated entity, this is for the duration of the SPC—generally, three years with provisions for two one-year extensions.

At June 2017 there were 34 SPCs—23 mandatory and 11 non-mandatory. Figure 1G provides a breakdown of the reported spend under each SPC for 2016–17.

Figure 1G

Reported SPC spend, 2016–17

|

SPC |

Mandatory or non-mandatory |

Estimated spend ($ million) |

|---|---|---|

|

DTF |

||

|

Staffing Services |

Mandatory |

346.7 |

|

Motor Vehicles |

Mandatory |

172.4 |

|

Master Agency Media Services |

Mandatory |

87.5 |

|

Electricity—Large Sites |

Mandatory |

84.6 |

|

Professional Advisory Services |

Mandatory |

71.0 |

|

Fuel and Associated Products |

Mandatory |

55.1 |

|

Security Services |

Mandatory |

46.6 |

|

Cash and Banking Services |

Mandatory |

26.6 |

|

Print Management Services |

Mandatory |

18.7 |

|

Electricity—Small and Medium Enterprise and Residential Sites |

Mandatory |

17.6 |

|

Stationery and Workplace Consumables |

Mandatory |

15.7 |

|

Natural Gas |

Mandatory |

14.5 |

|

Travel Management Services |

Mandatory |

13.9 |

|

Marketing Services Register |

Mandatory |

5.5(a) |

|

Document Mail Exchange (DX Services) |

Mandatory |

2.3 |

|

Fleet Disposals |

Mandatory |

1.2 |

|

Postal Services |

Non-mandatory |

1.0 |

|

Subtotal |

980.9 |

|

|

DPC |

||

|

Telecommunications Purchasing and Management Strategy |

Mandatory |

153.8 |

|

End User Computing Equipment Panel |

Mandatory |

79.7 |

|

IT Infrastructure Register |

Mandatory |

44.6 |

|

Microsoft Enterprise Agreement |

Non-mandatory |

25.5 |

|

Microsoft Licensing Solution Provider |

Non-mandatory |

– (b) |

|

Oracle Software and Support |

Non-mandatory |

22.0 |

|

Data Centre Facilities |

Non-mandatory |

14.9 |

|

Victorian Office Telephony Services |

Non-mandatory |

10.9 |

|

Multifunction Devices and Printers |

Mandatory |

7.7 |

|

Citrix Products and Services |

Non-mandatory |

5.5 |

|

VMware Enterprise Licensing Agreement |

Non-mandatory |

4.5 |

|

IBM Enterprise Licensing Agreement |

Non-mandatory |

2.9 |

|

Salesforce Customer Relationship Management |

Non-mandatory |

1.5 |

|

Intra-Government Secured Network |

Mandatory |

1.1 |

|

eServices Register |

Mandatory |

– (c) |

|

Subtotal |

374.6 |

|

|

DJR |

||

|

Legal Services Panel |

Mandatory |

113.1 |

|

Subtotal |

113.1 |

|

|

Cenitex |

||

|

Rosetta |

Non-mandatory |

0.7 |

|

Subtotal |

0.7 |

|

|

Total |

1 469.3 |

|

(a) DTF estimated spend, not actual spend reported by suppliers.

(b) Spend for this SPC is through the Microsoft Enterprise Agreement.

(c) Spend is not captured by DPC.

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR and Cenitex.

Appendix C outlines the scope of each SPC arrangement.

SPCs range from relatively stable goods and services, such as stationery and gas, to rapidly changing commodities, such as telecommunications and personal computers. The different characteristics of these goods and services affect the type of purchasing arrangements needed for each SPC, and influence the monitoring required.

Developing and managing SPCs

Figure 1H shows the key steps in developing and managing an SPC. The process begins with the lead agency developing a category strategy, which it uses to understand the market and potential for SPC development. In the next stage, building on the information contained in the category strategy, the lead agency prepares a business case to establish or renew an SPC.

Once the relevant minister approves the business case, the market is engaged and the lead agency executes the SPC and sets out the terms and conditions. The lead agency then develops a Category Management Plan (CMP) to monitor performance and drive continuous improvement.

Figure 1H

Process for developing and managing an SPC

Source: VAGO, based on DTF's Strategic Sourcing Procedures manual, 2016.

Benefits management

A lead agency should define the expected financial and non-financial benefits of an SPC so that progress against these can be monitored and managed throughout the life of the contract. This includes reviewing the benefits for continued relevance and achievability over time.

Figure 1I outlines a framework used to plan, capture and realise benefits.

Figure 1I

Benefits management framework

Source: VAGO, based on DJR Procurement Benefits Realisation Framework .

Benefits tracking is critical to a lead agency's ability to demonstrate an SPC's performance. A benefits management framework supports the achievement of the expected outcomes identified in the business case and the benefits finally secured on contract award.

Financial benefits are based on a question—if the SPC did not exist, would the service or goods cost more and, if so, by how much? The answer will be the financial benefit delivered by the SPC. Examples of financial benefits include cost savings through reduced pricing, increased discounts and more favourable payment terms.

Non-financial benefits can relate to environmental, social and risk management aspects. When assessing the impact of SPCs, potential non-financial benefits need to be considered. These can include:

- availability of environmentally friendly alternatives

- reduction in procurement risks through supplier vetting

- better service quality from suppliers as they come to understand government needs through repeat engagements

- reduced commercial and legal risks from a consistent set of negotiated and legally endorsed commercial terms and conditions used across government rather than several different agency-specific contracts.

DTF and DPC guidance makes SPC lead responsible for delivering the expected benefits or explaining variances when benefits do not meet expectations.

Benefits and risks of SPC arrangements

Figure 1J summarises the potential benefits and risks of SPC arrangements for government entities and suppliers.

Figure 1J

Potential benefits and risks of SPC arrangements

|

Entities |

|

|---|---|

|

Benefits |

Risks |

|

|

Source: VAGO, adapted from the Australian National Audit Office, May 2012, Establishment and Use of Procurement Panels.

SPC sourcing models

SPCs are either sole or multiple supplier arrangements, including panels or pre‑approved registers. Panels can be open or closed. Open panels can accept new suppliers during the term of the contract, closed panels cannot. Figure 1K outlines the different SPC sourcing arrangements.

Figure 1K

SPC sourcing arrangements

|

Sourcing model option |

Sourcing model description |

|---|---|

|

Sole supplier |

A lead agency contracts a single supplier to provide goods and services. This is a closed arrangement for a set period. Examples include gas, electricity, and cash and banking SPCs. |

|

Multiple supplier |

|

|

Master vendor |

Generally, an arrangement with a single supplier, providing subject matter expertise and market knowledge. The master vendor is responsible for developing partnerships and managing relationships with tier-2 suppliers to provide required services. Used to reduce complexity and administration in managing contracts and suppliers while ensuring a broader access to supply—for example, the Staffing Services SPC utilises a modified master vendor model. |

|

Broker |

Typically, an individual supplier arrangement, engaged to source products or services from a third party such as various manufacturers. Quotations are based on pre‑defined statements of work and used where market expertise and buying power is low to deliver better value for money—for example, the Print Management Services SPC. |

Source: VAGO, based on DTF's Strategic Sourcing Procedures manual, 2016.

1.5 Previous VAGO audits

In two previous VAGO audits of SPCs—Government Advertising and Communications and Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards—we found significant deficiencies with their management.

Government Advertising and Communications

This February 2012 audit examined the management of the Master Agency Media Services, Print Management Services and Marketing Services SPCs.

At the time of the audit, DPC was the lead agency for the Master Agency Media Services SPC. DTF was the lead agency for the Print Management Services and the Marketing Services SPCs, although DPC had been the lead agency until December 2009, when management transferred to DTF.

The audit made the following findings:

- DPC had not been effective in managing the contracts for the three SPCs reviewed. DPC did not monitor whether contracts met objectives or confirm if negotiated rates were competitive. In addition, there was little evidence that it assessed service provider performance or consistently monitored department and agency spending under each SPC.

- Management of the Print Management Services and Marketing Services SPCs improved significantly under DTF, with regular reporting from, and close coordination with, the service providers.

The audit recommended that DPC improve its management of the Master Agency Media Services contract, but in September 2015 the management of this contract also transferred to DTF.

Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards

This May 2012 audit examined how well DTF oversaw, and user departments managed, SPCs, including their understanding and management of contract leakage. The audit examined the Travel Management Services and the Stationery and Workplace Consumables SPCs.

The audit concluded that user departments had made significant savings from using these contracts. However, user departments and DTF had not fully realised potential savings because significant purchasing still occurred outside these contracts. Apart from the former Department of Justice, user departments had not understood or managed contract leakage.

The audit recommended that:

- public sector agencies should report and address expenditure outside of mandatory SPCs

- DTF should request an acquittal of contract leakage from participating agencies.

DTF noted in its response to the report that there were opportunities to work with public sector agencies to review the extent of contract leakage.

1.6 Why this audit is important

During 2014–15, VGPB reviewed its supply policies in response to the government's election commitments and broader operational feedback. The review identified a need for VGPB to adopt a stronger role in establishing, reporting and overseeing SPCs, which DTF oversaw prior to 1 July 2016.

It is timely to assess the extent to which SPCs provide value for money and optimise other procurement benefits, given the total value of Victorian Government agency expenditure on goods and services, including under SPCs, and the relatively recent change in SPC oversight arrangements (see Section 1.3).

1.7 What this audit examined and how

Our objective was to assess whether state government agencies are realising benefits in procurement by using SPCs. We examined whether:

- SPCs are delivering value for money

- SPCs are overseen effectively.

We included eight agencies in the scope of our audit:

- Cenitex

- DEDJTR

- DELWP

- DET

- DHHS

- DJR

- DPC

- DTF.

We also examined VGPB in its oversight role of state supply policies.

We examined a selection of SPCs based on factors such as strategic importance, spend and stage of contract lifecycle to assess the appropriateness of strategies, including governance, rules of use and reporting requirements. The scope of the audit included the collection of expenditure data from the seven departments' finance systems for the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2017.

Given the significant task of obtaining and analysing procurement data, we could not extend analysis to include the 2017–18 financial year.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The cost of this audit was $725 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the availability and quality of data used to inform category planning

- Part 3 examines VGPB's oversight role and how well lead agencies oversee and manage SPCs

- Part 4 examines whether effective arrangements are in place to monitor and evaluate the achievement of expected savings and benefits from SPCs

- Part 5 examines whether departments are using SPCs when purchasing goods and services, and how user and lead agencies manage contract leakage as required by contract agreements and VGPB policies.

2 Category planning

Effectively managing the Victorian Government's significant expenditure on goods and services is an opportunity to deliver or improve value for money for the community.

Spend across the VPS can be split into different expense and procurement categories. Good category planning relies on sound knowledge of the market, good quality procurement data and robust information systems to provide a comprehensive picture of spend.

VGPB guidance defines procurement categories as groupings of similar goods or services with similar suppliers. For example, a pen is a good whereas stationery could be the procurement category.

To understand procurement categories, VGPB and lead agencies need to know the goods and services that entities are purchasing, from whom and how much they pay their suppliers, both in unit rates and in total.

The FMA requires VGPB to establish and maintain a comprehensive database of departments' and supply markets' purchasing data, for access by departments. The FMA also provides VGPB with the power to request information and data from mandated agencies relating to the supply of goods and services.

The basis for developing a procurement category strategy is analysing and understanding spend, business requirements, supply and demand, and the market. The next step is to determine how these categories of expenditure can create value for stakeholders.

In some cases, category strategies will recommend aggregation of demand across government through SPCs. Other category strategies may recommend that agencies establish their own arrangements. What is critical is developing the right strategy for each category so that procurement is not driven by a 'one size fits all' approach.

This part examines the development of category strategies, including the availability and quality of data used to inform category planning.

2.1 Conclusion

VGPB and lead agencies do not have a complete picture of the goods and services public sector agencies purchase due to the lack of good quality procurement data and analysis tools. This limits their ability to fully harness the state's purchasing power and increases the risk that SPCs are not maximising value for money. Better information would enhance category planning by allowing insightful analysis of who is buying what, from which suppliers and at what cost. This information would also help identify new SPC opportunities and where the greatest benefits can be achieved.

VGPB has attempted to collect procurement information. However, it has not fully met its legislative responsibilities to establish and maintain a comprehensive database of purchasing data. This is mainly due to the absence of appropriate systems in departments and entities to capture this information. Departments and entities have designed and implemented their financial systems to capture spend data to predominantly meet the needs of financial reporting and payroll functions. They do not have complete procurement information such as volumes, unit prices and products purchased.

The actions underway to establish e-procurement systems , a common chart of accounts across agencies, and standard goods and services classifications are positive. However, this needs to be expedited to enable accurate data collection across departments and entities. There also needs to be a commitment from public sector agencies to improve data quality, and clear direction and support from DTF and VGPB to drive the proposed improvements, and capture and analyse the procurement data.

2.2 Development of category strategies

Effective and efficient purchasing requires a comprehensive picture of the spend profile and of stakeholder and business needs, as well as an analysis of markets . Figure 2A summarises key activities and questions leading to category strategy development and implementation.

Figure 2A

Category strategy development and implementation

Source: VAGO, based on DTF, Strategic Sourcing Procedures manual, 2016.

Although lead agencies undertake market analysis and consult with key stakeholders, including representatives from SPC users, to support category strategy development, VGPB and lead agencies also need detailed expenditure data to identify spend patterns. However, centrally captured, comprehensive and consistently categorised procurement data is lacking, as is a tool to analyse whole-of-government procurement spend.

The absence of appropriate technology and standard processes in departments is a feature of the decentralised and devolved approaches to financial management systems and reporting that arose from the new public sector financial management paradigms of the 1990s. While these approaches have had many positive impacts on improving financial governance and accountability, they have nevertheless created and perpetuated information silos that work against whole-of-government approaches.

What is missing is:

- a central e-procurement system to streamline and integrate procurement processes and information across departments

- a common chart of accounts across agencies subject to the FMA to consistently capture and code goods and services expenditure to allow better assessment and analysis

- standard goods and services classification processes—that is, the use of the United Nations Standard Products and Services Code or the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC).

Departments have expressed interest in the use of a central e-procurement system. However, securing agreement across departments on how to meet all of their needs has proven to be complicated.

|

The Victorian Secretaries' Board comprises the Secretaries of each department, the Chief Commissioner of Police and the Victorian Public Sector Commissioner. |

In 2016 and 2017 the Victorian Secretaries' Board endorsed Statements of Direction to move towards a whole-of-Victorian Government approach to implementing information technology (IT) systems that will support business areas, including procurement. The Victorian Secretaries' Board agreed that DPC will develop a Statement of Direction on procurement systems for the VPS that will outline the high-level requirements for consistent procurement systems in the Victorian Government.

The Statements of Direction aim to provide an agreed position across departments to upgrade and modernise IT systems to simplify processes and better manage resources. This technology has a five-year implementation time line.

VGPB advised that it expects the proposed adoption of e-procurement systems, a common chart of accounts and an expenditure classification framework to play a key support role in better managing and overseeing the state's procurement spend.

While the proposed improvements in systems and processes to capture procurement data are encouraging, VGPB and DTF need to centrally drive the analysis of this procurement data to better understand existing, and identify new, SPC opportunities.

VGPB's role in capturing procurement data

The FMA requires VGPB to establish and maintain a comprehensive database of purchasing data from departments and specified entities.

While the lack of standardised systems and business rules that govern how agencies collect and classify procurement information has hampered its ability to do so, VGPB has responsibility for fostering improvement in these areas. However, VGPB has insufficient resources to actively lead and coordinate a whole-of-government approach to procurement technology.

VGPB has attempted to meet this function by using data collected from ASRs provided by departments and specified entities. However, this information is limited because it includes only:

- contract expenditure for non-construction goods and services valued at more than $100 000

- procurement activity plans that outline planned procurement activity for the next 12–18 months.

This information does not provide the detailed spend data—unit price, quantity and supplier details—needed to develop category strategies. Consequently, this is not comprehensive purchasing data, which the FMA requires VGPB to collect.

VGPB review of accounts payable data

The absence of comprehensive purchasing data impacts VGPB's ability to meet a key strategic direction in its Strategic Plan 2016–2021 that requires it 'to develop a prioritised program of future multi-organisation procurement opportunities using SPCs or other forms of procurement models in consultation with VPS organisations'. The requirement to collect this purchasing data has been in place since the VGPB was established in 1995, however it has taken over 20 years to address this. In November 2017 it worked with DTF to commission a desktop review of accounts payable data from the seven departments, VicRoads and Victoria Police, to identify procurement saving opportunities. The review used data from 2014–15 and identified savings opportunities of between:

- $70 million and $154 million by establishing new SPCs

- $49 million and $106 million across existing SPCs, by expanding their scope or by practicing better category management.

The achievement of some of these savings depends on improved technology. The potential implementation of a whole-of-government e-procurement system is likely to enhance DTF's ability to realise these savings.

In the absence of a data classification framework, the review needed to make assumptions when classifying data. For example, if a supplier was on multiple SPCs—for example, PAS and the eServices Register—the review assigned it to one SPC. The data also did not reflect the item that the agency purchased, only the supplier and the value.

Given the limitations of the data, the review recommended a more detailed investigation of individual categories to verify the savings. In May 2018 DTF advised the Minister for Finance that a further 'deep dive' is not warranted at this stage due to:

- DTF activity already underway to assess new SPC opportunities—for example, as part of the government's Regional Partnership Policy, DTF is investigating opportunities to aggregate purchasing contracts in regions, and, is considering opportunities to aggregate education and training services in regional locations

- the significant level of expenditure identified as relating to building and construction, which is outside VGPB's scope

- this audit, which includes more up-to-date data.

Potential changes to VGPB functions

VGPB advised that through the evolution of technology, the interpretation of VGPB's function under the FMA to 'establish and maintain a comprehensive database of purchasing data' has changed to reflect a more complex data management role than envisaged in 1994 when VGPB was established.

While we acknowledge that technology has changed, all government agencies are required to adapt their processes to align with such changes. The evolution of technology should have made it easier for VGPB to establish and maintain a comprehensive database of purchasing data.

In February 2015, DTF undertook a legal review of VGPB's functions and noted that because the purchasing database needs to be comprehensive, the threshold for data collection set by the FMA is high. The legal review stated that VGPB should 'query whether this function needs to be reviewed in light of current practice and resources. This may depend on the kinds of data that it would be useful to collect and why. '

In March 2017, VGPB put forward a legislative proposal to remove the function that requires it 'to establish and maintain a comprehensive data base of purchasing data'. The removal of the function is subject to the passing of the Financial Management and Constitution Acts Amendment Bill 2017, which was introduced to Parliament in November 2017. If this function is not reassigned to another body, it is unlikely that this important database will be delivered.

Better practice in another jurisdiction

As Figure 2B shows, the Western Australian (WA) Department of Finance provides a better practice example of how a central procurement body can capture procurement data to analyse government spending patterns and help identify opportunities to establish SPCs.

Figure 2B

WA Department of Finance interactive dashboard reports of goods and services expenditure

|

The WA Department of Finance has, since 2006 on behalf of the State Supply Commission, published an annual report—Who Buys What and How—on goods and services expenditure for government. Agencies provide the Department of Finance with expenditure information categorised by the United Nations Standard Products and Services Code. The report is a valuable source of information for suppliers in identifying opportunities to provide goods and services and for government in identifying new aggregated purchasing opportunities. More recently, the WA Department of Finance has used this information and data from sales reports provided by suppliers to develop a Who Buys What and How interactive dashboard that government agencies and the public can access. The public version excludes commercially sensitive information. The dashboard, launched in July 2018, will help agencies understand the spend in different expenditure categories and identify potential contract aggregation opportunities. The interactive dashboard provides greater transparency of agency expenditure with the ability to 'drill down' several levels for more detailed information. Appendix D shows screenshots of the type of information displayed by the dashboard. |

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by the WA Department of Finance.

SPC category strategies

In developing a category strategy, lead agencies typically prepare a draft strategy for discussion with the designated user reference group, which comprises key user representatives from each of the departments. Lead agencies also undertake extensive market analysis, including identifying stakeholders and business needs.

However, the lack of accessible, quality expenditure data has compromised the development of category strategies. Lead agency knowledge of procurement expenditure is limited to departments' and agencies' spend on SPCs. Also, this data comes from suppliers, rather than from users. Consequently, VGPB and lead agencies have no visibility of all the spend data in an expenditure category.

In comparison, the New South Wales (NSW) Government uses a system called NSWBuy. This is a one-stop shop for all NSW Government procurement. Suppliers use the system to tender for government work and manage their product catalogues, and buyers from government agencies use it to access these product catalogues to make a purchase. Buyers can build shopping lists from the product catalogue with current unit rates and purchase from whole‑of‑government contracts online.

Users purchase goods and services centrally and the system records the products that agencies have ordered, including the rates paid and quantities ordered. This information can then be used to perform a spend analysis at a product level for a department or at the whole-of-government level. This analysis of an entire category of spend can underpin the development of category strategies.

Victoria bases decisions about which SPC to establish or renew on analysis of the supplier-reported data of spend on existing SPCs, rather than on comprehensive expenditure data from all users in an entire category of goods and services. For this reason, the category strategies in place relate to specific SPCs, rather than entire expenditure categories, which results in potential missed opportunities to realise further benefits.

Travel category

The travel category strategy does not include an analysis of all government expenditure on travel. This data is not available to the lead agency, DTF. DTF is able to analyse spend data through the Travel Management Services SPC only, as reported by the travel management supplier, not by government users. The December 2014 category strategy for the Travel Management Services SPC noted the absence of complete and reliable spend data, given DTF did not mandate the booking of accommodation in Victoria under the previous SPC. This means that DTF lacked comprehensive spend data on Victorian accommodation.

Our review of departments' accounts payable data identified that more than $4 million was spent on accommodation in Victoria in 2016–17 outside the SPC. This is almost half the value of what those seven departments spent on the SPC that year. Since establishing the current Travel Management Services SPC, DTF has acknowledged this and has worked with user departments to increase the number of Victorian accommodation bookings that users make through the SPC. These efforts have resulted in a doubling of accommodation bookings from 2016–17 to 2017–18. As usage of the Travel Management Services SPC increases, DTF will have a more comprehensive view of travel spend across the state. However, as the Travel Management Services SPC is only mandatory for accommodation outside Victoria, DTF will still only capture travel spend booked through the SPC, not the entire category spend.

Professional Advisory Services SPC

As Figure 2C shows, the PAS SPC provides a case study of the importance of category planning in establishing an SPC. This SPC commenced in September 2015 and expires in August 2019. It offers Commercial and Financial Advisory Services (CAFAS ), Tax Advisory Services, Financial Assessment Services and Probity Services . DTF has broken these four categories down into 20 sub‑categories. Before DTF established the current PAS SPC, these four services were available as four separate SPCs.

DTF has several challenges with the PAS SPC:

- Its size makes management hard.

- There is limited visibility of the hourly rates charged.

- The high number of sub-categories makes tracking compliance hard.

Figure 2C

PAS category planning

|

PAS is an open panel SPC—suppliers can join at any time during the contract term following a tender process. DTF adopted the open panel model to align with the objective of providing greater access to government business. PAS also aims to streamline government engagement with service providers by merging the four separate service contracts—CAFAS, Tax Advisory Services, Financial Assessment Services and Probity Services—into a single SPC. When developing the PAS SPC category strategy and business case, no spend data was available for past CAFAS services engaged by government. Spend on CAFAS services has subsequently been shown to make up approximately 90 per cent of spend on the PAS SPC in 2016–17. The March 2015 business case, for combining the four SPCs into one PAS SPC, states that DTF expected the annual contract value for the PAS SPC to be approximately $25 million a year. The actual value of the PAS SPC in 2016–17 was more than $71 million. At contract commencement, DTF appointed 106 suppliers to the panel, with an additional 124 suppliers added. The sheer size of the PAS SPC, with 230 suppliers, has presented DTF with challenges in managing the contract. Without an automated system, the management of the SPC has primarily focused on contract administration and contract refreshes to ensure that the panel continues to deliver on the government's commitment to support local jobs. DTF has lacked the resources to undertake more strategic contract management activities for the PAS SPC such as sharing savings opportunities with users and ensuring compliance with ceiling rates. Given the significant challenges, DTF has commenced a review of the PAS SPC category strategy. As part of the process, DTF advises it will engage and collaborate with the chief procurement officers of the seven departments and the PAS SPC user reference group to identify improvement opportunities in the lead up to a new PAS SPC. DTF also intends to engage an external subject matter expert to obtain market intelligence and benchmarking in the PAS industry and consider how the current PAS SPC compares with best practice in the broader market. While the review and collaboration with stakeholders will provide greater insight into user needs and the market, the issue around the lack of quality data remains because accurate and comprehensive spend data on professional services across government is still not captured. |

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by DTF.

2.3 Department procurement spend

Analysis of departmental expenditure data

VGPB does not have a comprehensive database of purchasing data, so we used our access powers to obtain, consolidate and analyse financial data from the seven departments for the three financial years from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2017.

Appendix E includes a description of our methodology and screenshot from our business intelligence tool.

Using this unique dataset, we obtained insights into:

- the goods and services that are purchased (procurement category analysis)

- who purchases the goods and services (department analysis)

- who departments purchase from (supplier analysis).

We can also use our tool to analyse any combination of the above. For example, we can analyse a department's procurement spend in professional services, analyse which suppliers the department engages the most and when payments mostly occur.

Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification

We used ANZSIC to identify expenditure categories for departmental spend. As Figure 2D shows, ANZSIC is a hierarchical classification with four levels. At the divisional level, the main purpose is to provide a broad overall picture of expenditure—see Appendix F for descriptions of each division. The subdivision, group and class levels provide increasingly detailed dissections of these categories for the compilation of more specific and detailed expenditure information.

Figure 2D

ANZSIC classification

Source: VAGO, based on ANZSIC.

Departmental operational expenditure

Figure 2E displays total departmental operational expenditure, by ANZSIC divisions, for 2014–15 to 2016–17. This expenditure includes goods and services, as well as inter-governmental spend, superannuation and grants.

Figure 2E

Departmental operational expenditure summary, by ANZSIC division categories, 2014–15 to 2016–17

|

Division |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public Administration and Safety |

9 748.5 |

8 928.6 |

10 140.9 |

28 818.0 |

|

Education and Training |

5 253.4 |

6 174.6 |

5 053.5 |

16 481.5 |

|

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services |

1 758.2 |

1 809.9 |

2 452.0 |

6 020.1 |

|

Health Care and Social Assistance |

1 603.4 |

1 722.7 |

2 011.2 |

5 337.3 |

|

Construction |

1 234.3 |

505.1 |

2 150.2 |

3 889.6 |

|

Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services |

1 130.2 |

1 106.4 |

1 338.3 |

3 574.9 |

|

Financial and Insurance Services |

1 184.1 |

752.3 |

449.6 |

2 386.0 |

|

Arts and Recreation Services |

515.6 |

653.3 |

587.9 |

1 756.8 |

|

Administrative and Support Services |

491.0 |

497.8 |

501.5 |

1 490.3 |

|

Other Services |

391.9 |

500.8 |

443.5 |

1 336.2 |

|

Transport, Postal and Warehousing |

287.8 |

211.5 |

396.3 |

895.6 |

|

Information Media and Telecommunications |

233.7 |

273.6 |

279.0 |

786.3 |

|

Wholesale Trade |

230.8 |

248.0 |

291.7 |

770.5 |

|

Retail Trade |

243.2 |

246.1 |

208.2 |

697.5 |

|

Manufacturing |

161.0 |

161.0 |

217.4 |

539.4 |

|

Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services |

94.4 |

115.2 |

161.3 |

370.9 |

|

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing |

65.9 |

71.2 |

56.4 |

193.5 |

|

Accommodation and Food Services |

35.2 |

32.9 |

37.1 |

105.2 |

|

Mining |

5.6 |

3.1 |

2.4 |

11.1 |

|

Uncategorised |

1 339.4 |

1 117.5 |

1 690.2 |

4 147.1 |

|

Total |

26 007.6 |

25 131.6 |

28 468.6 |

79 607.8 |

Note: Uncategorised expenditure reflects items with missing or invalid Australian Business Numbers in the data we extracted from agencies. Further follow up could have identified these items, however, this was not warranted. It should be noted that, as a result, expenditure amounts in the other categories may be slightly understated, but not materially. Data provided by DHHS excludes payments pertaining to grants, housing procurement cards, clients (for example, concessions, gas, electricity and water, assistance), bushfire and flood disasters, and payroll, given the sensitive nature of the information.

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Around $60.5 billion (76 per cent) of the total expenditure of $79.6 billion during the three-year period is concentrated across five key ANZSIC division categories.

Construction had the largest rise in expenditure across the three years, increasing by $915.6 million—followed by Professional, Scientific and Technical Services by $693.8 million.

In percentage terms, Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services had the greatest increase—71 per cent.

Operational expenditure by departments

Figure 2F shows that DEDJTR (31 per cent) and DET (26 per cent) had the largest spends during 2016–17, at $8.8 billion and $7.4 billion respectively. Their combined expenditure made up 57 per cent of the total spend analysed ($28.5 billion).

Figure 2F

Proportion of operational expenditure by department, 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Goods and services purchased

Of the $28.5 billion expenditure across the seven departments in 2016–17, we identified $3.3 billion (11.6 per cent) as spend on goods and services, as Figure 2G shows. The remaining $25.2 billion includes inter-governmental payments, superannuation and grants.

Figure 2G

Departmental goods and services expenditure, 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Of the $3.3 billion in departmental spend on goods and services, departments spent $0.76 billion (23 per cent) through an SPC. This strongly indicates that opportunities to aggregate purchasing through new SPCs remain unrealised.

Figure 2H shows the total goods and service expenditure by ANZSIC divisions for 2016–17.

Figure 2H

Goods and services expenditure summary by ANZSIC divisions, 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Expenditure in the top five ANZSIC goods and services divisions (excluding uncategorised) comprises around $2.2 billion, or 67 per cent, of the total 2016−17 goods and services spend.

Appendix G provides a further breakdown of 2016–17 departmental spend on goods and services by subdivision, group and class.

Who purchases the goods and services?

As Figure 2I shows, the combined expenditure for DELWP, DJR and DHHS during 2016–17 makes up 72 per cent of the total goods and services spend for the financial year.

Figure 2I

Proportion of goods and services expenditure by department, 2016–17

Note: Figures may not total 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Figure 2J shows the breakdown of the top five expenditure categories by departments.

Figure 2J

Top five expenditure categories by department, 2016–17

Note: Uncategorised spend not included.

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Who departments spend with

In 2016–17 the departments purchased goods and services from more than 20 000 individual suppliers. Figure 2K shows the top 10 suppliers, by value, used by at least four departments. The value of spend across these suppliers is $480.3 million (15 per cent) of total goods and services expenditure.

Figure 2K

Top 10 goods and services suppliers, including ANZSIC divisions, 2016–17

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by DTF, DPC, DJR, DHHS, DET, DELWP and DEDJTR.

Eight of the 10 suppliers in Figure 2K are nominated on an SPC. The two suppliers that are not part of a current SPC arrangement receive the highest spend (Cushman & Wakefield) and fourth-highest spend (DTZ, a UGL Company). Spend to these suppliers falls within the Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services expenditure division. The majority of this expenditure is for office accommodation and property management services of government‑leased and owned properties provided by Cushman & Wakefield through the Shared Service Provider within DTF.

New SPC procurement opportunities

Lead agencies can achieve further savings by exploring new SPC opportunities. Retenders for existing SPCs typically occur in a mature market where government has already realised the initial savings from collective procurement, which limits further benefits.

Using our tool, we identified areas of common goods and services expenditure where current SPCs do not exist. These are categories where the Victorian Government can potentially realise benefits if departments and other public sector agencies work collaboratively to aggregate spend and coordinate market engagement and procurement activity:

- Accounting services, which had a $37.1 million total departmental spend in2016–17. DHHS had the largest spend—28 per cent—followed by DTF and DPC at 26 per cent combined, and DET at 19 per cent. The remaining three departments made up 27 per cent. The top two suppliers account for 94 per cent of the total spend.

- Market analysis and statistical services, which had a $13.4 million total departmental spend in 2016–17. DET spent 27 per cent of this, DHHS 21 per cent, DEDJTR 17 per cent and other departments purchased the remaining 35 per cent. The top five suppliers account for 52 per cent of the total spend.

For these three categories, it is likely that departments are currently paying different rates for the same goods and services, leading to potential inefficiencies and waste.

Other new SPC opportunities may also be available. However, lead agencies will need to use their knowledge of the relevant markets, and comprehensive and quality spend data, to undertake more detailed investigation.

3 Overseeing and managing SPCs

VGPB is responsible for monitoring the compliance of departments and specified entities with VGPB supply policies.

Under VGPB's oversight, lead agencies are responsible for the day-to-day management of SPCs. Each SPC is different, however the fundamental principles for managing contract performance are the same.

Effective SPC management ensures:

- a high standard of service and quality delivered by the suppliers

- value for money

- reduced risk

- the ability to address market changes or developments

- the identification of poor contractor performance.