Water Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits

Overview

This report covers the results of our financial audits of 20 entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. The report informs Parliament about significant issues arising from the audits of financial and performance reports and augments the assurance provided through audit opinions included in the respective entities’ annual reports.

Parliament can have confidence in the financial and performance reports of the water industry for the year-ended 30 June as clear audit opinions were issued on the 20 financial reports and 16 performance reports.

For the year-ended 30 June 2013 the 19 water entities generated combined net profits before income tax of $110 million in 2012–13, $497 million or 82 per cent lower than the prior year, predominantly due to Melbourne Water reporting a loss of $45.1 million compared to a profit of $372.8 million in 2011–12. The loss was due to the water price freeze, and a $300 million or 120 per cent increase in its finance costs following the Wonthaggi desalination plant’s completion.

The report highlights the increase in borrowings resulting from investment in infrastructure assets and payment of dividends to government, and its effect on the financial results and long-term financial sustainability of the water industry. Servicing the growing debt and repaying the debt in the future are key challenges for the water industry.

Water Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2012

PP No 290, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on Water Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits.

This report summarises the results of the financial audits of the 19 water entities and one controlled entity for the year-ended 30 June 2013.

It informs Parliament about significant issues identified during our audits and complements the assurance provided through individual audit opinions included in the entities' annual reports.

The report highlights the increase in borrowings resulting from investment in infrastructure assets and payment of dividends to government, and its effect on the financial results and long-term financial sustainability of the water industry. Servicing the growing debt and repaying the debt in the future are key challenges for the industry.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

12 December 2013

Audit summary

The Victorian water industry consists of 20 entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. The 19 water entities provide water, sewage and trade waste services to the Victorian community.

This report presents the results of our financial audits of these 20 entities. It provides a detailed analysis of their financial and performance reporting, financial results and financial sustainability. It also comments on the effectiveness of internal controls, in particular, information technology security, change management, procurement and treasury management.

Conclusions

Parliament can have confidence in the financial and performance reports of the water industry for the year-ended 30 June 2013.

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on the 20 financial reports which means the audited financial information presents fairly the entities' transactions and cash flows for the 2012–13 financial year, and their assets and liabilities as at 30 June 2013.

Unqualified audit opinions were also issued on all 16 performance reports as the audited information presents fairly the results against performance indicators for the 2012–13 financial year.

Findings

Financial and performance reporting

While unqualified audit opinions were issued on the financial and performance reports there are opportunities for the 19 water entities to reduce their operating costs and further improve the timeliness of their reporting.

Consistent with the prior year, the three metropolitan retailers did not prepare and submit performance reports for audit. While they included the required financial and non-financial indicators as a separate report within their annual reports, the information was unaudited. To provide Parliament with reasonable assurance that the performance information is reliable and accurate, the entities should submit their performance reports for audit.

The usefulness of the performance reports of the 16 entities currently required to submit their reports for audit is limited because of the disconnect between a water entity's corporate planning processes and the performance reporting requirements for 2012–13, whereby targets were not set for a number of indicators reported against.

The Audit Act 1994 empowers the Auditor-General to audit any performance indicators in the report of operations of an audited entity to determine whether they:

- are relevant to the stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity's actual performance

- fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

At the time of preparing this report we have limited our opinions on performance reports of water entities to fair presentation and compliance with the legislative requirements.

During 2012–13 a water industry performance reporting working group evaluated the relevance and appropriateness of a suite of proposed key performance indicators.

The water entities were then required to reflect the agreed set of key performance indicators in their 2013–14 corporate plans, with targets to be set for all indicators.

From 2013–14 onwards audit opinions relating to the performance reports will also conclude on the relevance and appropriateness of the performance indicators and whether they fairly present performance.

Financial results

In 2011–12 Melbourne Water, City West Water, South East Water, Yarra Valley Water and Western Water collected payments from customers to cover the costs of purchasing water from the Wonthaggi desalination plant. However, due to delays in commissioning the plant, the plant was not operational and the amounts paid by customers were not needed.

From 1 July 2012 water entities began returning the payments to customers via a 12 month price freeze. At 30 June 2013, the Essential Services Commission estimated that the water entities had returned $265 million to customers. A total of $167 million was returned via the price freeze. In addition, the three metropolitan retailers and Western Water provided rebates of $98 million to eligible customers by 30 June 2013.

In 2012–13, the 19 water entities generated a combined net profit, before income tax, of $110 million, a decrease of $497 million or 82 per cent from the prior year. The overall decrease was predominantly due to Melbourne Water reporting a loss of $45.1 million compared to a profit of $372.8 million in 2011–12. Their decrease was due to the price freeze and a $300 million or 120 per cent increase in its finance costs, following the desalination plant achieving practical completion on 17 December 2012. The water industry also experienced a 16 per cent increase in operating costs while revenue grew by 2 per cent only.

Interest bearing liabilities increased by $5.4 billion, or 59 per cent, in 2012–13, due predominantly to the recognition of the desalination plant as a finance lease by Melbourne Water. The industry accessed new borrowings of approximately $1 billion to finance the construction of infrastructure assets and to facilitate the payment of dividends.

Financial sustainability

Over the past five years, interest bearing liabilities have increased by $10.3 billion, or 248 per cent, with finance costs now accounting for 21 per cent of the water industry's total operating costs each year. Accordingly, it is critical that water entities effectively manage interest rate risk.

Servicing the growing debt and repaying that debt in the future are key challenges for the water entities. The ability of one metropolitan water entity to repay its debt is currently rated as low and another may encounter difficulties in repaying debt in the future.

Four entities were rated as having a high financial sustainability risk at 30 June 2013 due to the magnitude of their operating losses. This is an outcome of the pricing model that regulates the prices entities can charge their customers for water and services provided. This issue is one of a number of matters being considered by a Water Industry Financial Sustainability (WIFS) working group established during 2011–12.

Information technology

There is significant reliance on information technology (IT) by the water industry. Information held by water entities about employees, customers and suppliers, and the financial and operational aspects of the business can be highly sensitive and needs to be protected from unauthorised access, theft or manipulation.

The IT controls over financial reporting are tested annually during our financial report attest audits. In 2012–13 we found that the controls tested were adequate for producing reliable, materially accurate and timely financial reports. Nevertheless, a number of areas for improvement were identified as IT control weaknesses were identified at 11 of the 19 entities during 2012–13.

Twenty-two IT control issues raised in previous years financial audits remained unresolved at 30 June 2013. The failure to address them reflects poorly on both the entities' governing bodies and their management.

The water entities can strengthen their controls to protect information from unauthorised access, theft or manipulation, to ensure the continuity of service provision and to guard against the emergence of external threats and new security risks.

Procurement

The water industry spent around $1.2 billion on goods and services and $1.5 billion on capital in 2012–13. Procurement frameworks were assessed as generally adequate. However, the high incidence of noncompliance with procurement policies, procedures and control activities identified by internal audits indicate there are opportunities for the governing bodies and management to improve practices.

Our audit revealed that conflict of interests declarations are not always completed by members of tender evaluation panels. This means that water entities could not demonstrate they had mitigated the risk of bias in the evaluation process, and that integrity had been maintained in the tender process.

Treasury management

The importance of an effective treasury function has increased over the past five years as the significant investment in new infrastructure across the water industry has been largely funded by new borrowings. An effective treasury function should monitor and manage cash flows to minimise borrowing costs while providing liquidity to meet obligations when they fall due.

Controls over treasury management at most water entities were established, however, the level of compliance with the approved policies and procedures varied. Improvements can be made with respect to compliance with the Department of Treasury and Finance Treasury management guidelines at some entities.

Four water entities also breached their own treasury management policies by not adhering to maturity profiles. Others did not align their borrowings with specific capital projects.

One entity delayed final payment to a contractor as insufficient funds were available when payment was due. It consequently incurred a penalty interest charge of 18 per cent on the outstanding amount, wasting approximately $90 000.

There is a need for the Department of Treasury and Finance to more actively oversight treasury management by the water entities.

Recommendations

That water entities:

- review their processes for capturing and calculating commitments and the training and/or briefing sessions provided to staff to improve the quality, completeness and accuracy of the information included in the financial report

- further refine their financial reporting processes by preparing shell statements, performing materiality assessments and rigorous analytical reviews, and having adequate security to protect and safeguard sensitive information.

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries:

- revisit the model performance report to assist the water entities in achieving a greater degree of compliance with the performance reporting requirements—including the explanation of variances between targets and actual performance, and between years.

That water entities:

- further refine their performance report preparation processes to reduce costs and achieve efficiencies in the future

- address information technology control weaknesses in a timely manner in order to ensure sound internal controls are in place and are operating effectively to protect information from unauthorised access, theft or manipulation, to ensure continuity of service provision and to guard against the emergence of external threats and new security risks

- develop and implement comprehensive information technology security and change management policies and procedures

- establish an information technology steering committee to oversight all information technology-related matters including risk management, security and change management

- improve reporting to the information technology steering committee on matters such as risk management, information technology security, change management and network breaches and intrusions

- implement a periodic review of user access to confirm that access rights are commensurate with staff member's roles and responsibilities, and regularly monitor the use of generic and privileged user accounts

- require each member of a tender evaluation panel to complete a conflict of interest declaration at the start of the evaluation process

- address recommendations arising from internal audits in a timely manner and report progress to the audit committee or the board

- improve the monitoring of their debt maturity profiles in order to ensure compliance with approved policies, and to confirm the availability of funds to meet their contractual obligations as and when they fall due.

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries:

- take a more active role in overseeing the treasury management activities of entities, including their compliance with the requirements of the Department of Treasury and Finance's Treasury management guidelines.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, the Department of Treasury and Finance, the Treasury Corporation of Victoria, the Essential Services Commission and the 20 entities with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The Victorian water industry consists of 20 entities, comprising 19 water entities and one controlled entity. All entities are wholly owned by the state. The entities are stand‑alone businesses responsible for their own management and performance. The 19 water entities are expected to adopt sustainable management practices which give due regard to environmental impacts and which allow water resources to be conserved, properly managed, and sustained.

This report provides the results of the financial audits of the 20 entities, and is one of a suite of Parliamentary reports on the results of the 2012–13 financial audits conducted by VAGO. The full list of reports can be found in Appendix A of this report.

Figure 1A lists the legal and trading names of the 20 entities that comprise the Victorian water industry.

Figure

1A

Water entities and controlled entity

Legal name |

Trading name |

|---|---|

Metropolitan sector |

|

Wholesaler |

|

|

Melbourne Water Corporation |

Melbourne Water |

Retailers |

|

|

City West Water Corporation South East Water Corporation Yarra Valley Water Corporation |

City West Water South East Water Yarra Valley Water |

Regional urban sector |

|

Barwon Region Water Corporation |

Barwon Water |

Central Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

Gippsland Water |

Central Highlands Region Water Corporation |

Central Highlands Water |

Coliban Region Water Corporation |

Coliban Water |

East Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

East Gippsland Water |

Goulburn Valley Region Water Corporation |

Goulburn Valley Water |

Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water Corporation |

GWMWater |

Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water Corporation |

Lower Murray Water |

North East Region Water Corporation |

North East Water |

South Gippsland Region Water Corporation |

South Gippsland Water |

Wannon Region Water Corporation |

Wannon Water |

Western Region Water Corporation |

Western Water |

Westernport Region Water Corporation |

Westernport Water |

Rural sector |

|

Gippsland and Southern Rural Water Corporation |

Southern Rural Water |

Goulburn-Murray Rural Water Corporation |

Goulburn-Murray Water |

Controlled entity |

|

Watermove Pty Ltd |

Watermove |

Note:

Watermove is a controlled entity of Goulburn-Murray Water.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.1.1 Recent changes to the metropolitan retail water entities

The three metropolitan water retailers, namely City West Water Limited, South East Water Limited and Yarra Valley Water Limited were established as public companies under the State Owned Enterprises Act 1992 and were subject to the Corporations Act 2001. However, in 2012 the Water Amendment (Governance and Other Reforms) Act 2012 established three statutory authorities, City West Water Corporation, South East Water Corporation and Yarra Valley Water Corporation, as their successors in law.

While their legal form changed, effective 1 July 2012, there was no change to the boundaries, operations, functions and services of the entities and the pre‑existing property, rights and liabilities were also transferred to the statutory authorities.

City West Water, South East Water and Yarra Valley Water now operate under the provisions of the Water Act 1989. From a financial reporting perspective they must comply with the Financial Management Act 1994 and the Financial Reporting Directions of the Minister for Finance.

The three public companies were deregistered by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission on 20 March 2013.

1.1.2 Watermove

Watermove is a controlled entity of Goulburn-Murray Water (G-MW). At a board meeting on 10 August 2012 the directors of Watermove resolved to discontinue the operations of the company. The company ceased trading on 13 August 2012.

G-MW investigated the sale of the business and its assets during 2012–13, however, no agreement was reached with potential buyers. As a result, Watermove remains a controlled entity of G-MW and a financial report was prepared and audited for the financial year-ended 30 June 2013.

1.2 Structure of this report

Figure 1B outlines the structure of this report.

Figure 1B

Report structure

Part |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Financial reporting |

Outlines the financial reporting framework and comments on the timeliness and accuracy of financial reporting by the 19 water entities and one controlled entity. It compares practices in 2012–13 against better practice, legislated time lines and past performance. |

Part 3: Performance reporting |

Outlines the performance reporting framework, comments on the timeliness and accuracy of performance reporting and compares practices in 2012–13 against better practice and past performance. Details work undertaken by the industry to improve the usefulness of performance reports and reiterates our intention to further develop our audit of the performance reports in future periods. |

Part 4: Financial results |

Illustrates the financial results of the 19 water entities, including financial performance for 2012–13, and financial position at 30 June 2013. |

Part 5: Financial sustainability |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability of the 19 water entities obtained from analysing the trends of seven financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. |

Part 6: Information technology |

Summarises common information technology general control weaknesses and comments on the information technology security and change management controls at the 19 water entities. |

Part 7: Procurement |

Assesses the procurement controls at the 19 water entities. |

Part 8: Treasury management |

Assesses the treasury management controls at the 19 water entities. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Audit of financial reports

A financial report is a structured representation of financial information, which usually includes accompanying notes, derived from accounting records. It indicates whether an entity generated a profit or loss and details an entity's assets and obligations at a point in time or the changes therein for a specified reporting period in accordance with a financial reporting framework.

An annual financial audit has two aims:

- to give an opinion consistent with section 9 of the Audit Act 1994, on whether financial reports are fairly stated

- to consider whether there has been wastage of public resources or a lack of probity or financial prudence in the management or application of public resources, consistent with section 3A(2) of the Audit Act 1994.

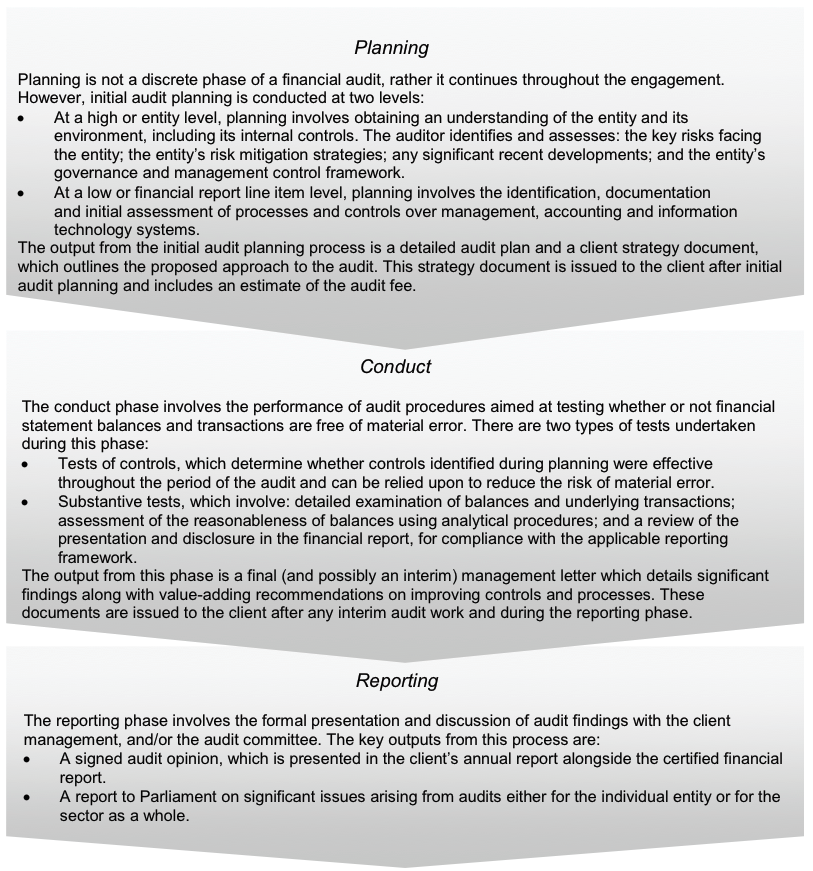

The framework applied in conducting our financial audits is set out in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Financial audit framework

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.3.1 Audit of internal controls relevant to the preparation of the financial report

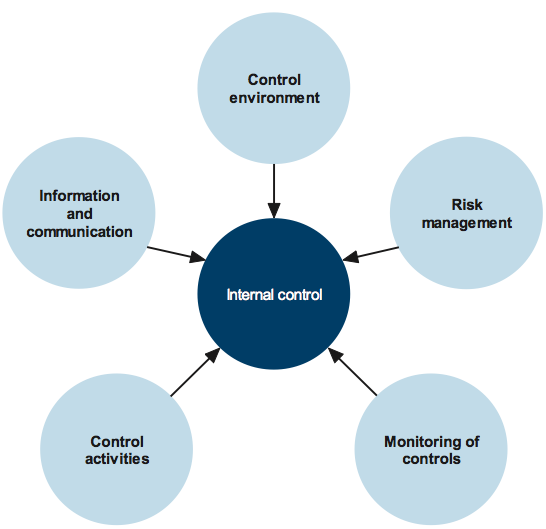

Integral to the annual financial audit is an assessment of the adequacy of the internal control framework, and the governance processes, related to an entity's financial reporting. In making this assessment, consideration is given to the internal controls relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial report, but this assessment is not used for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control.

Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely internal and external reporting.

An explanation of the internal control framework, and its main components, are set out in Appendix B. An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework.

Internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a 'qualified' audit opinion because often an entity will have compensating controls in place that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report. A qualification is warranted only if weaknesses cause significant uncertainty about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported.

Weaknesses in internal controls found during the audit of an entity are reported to its chairman, the managing director and audit committee in a management letter.

Our reports to Parliament raise systemic or common weaknesses identified during our assessments of internal controls over financial reporting, across the water industry.

1.4 Audit of performance reports

A performance report is a statement containing predetermined performance indicators, financial and/or non-financial, the targets and the actual results achieved against the indicators for that financial year, with an explanation for any significant variance between the results and targets.

The Audit Act 1994 empowers the Auditor-General to audit any performance indicators in the report of operations of an audited entity to determine whether they:

- are relevant to the stated objectives of the entity

- are appropriate for the assessment of the entity's actual performance

- fairly represent the entity's actual performance.

The Auditor-General uses this authority to audit the performance reports prepared by the water industry under Financial Reporting Direction 27B Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information.

1.5 Conduct of water entity financial audits

The audits of the 19 water entities and one controlled entity were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $192 500.

1.6 Subsequent events

1.6.1 Third regulatory period – Water Plan 3

Since 1 January 2004 the Essential Services Commission (ESC) has been responsible for regulating and approving the price each water entity may charge its customers for supplying water and providing sewage services.

In October 2012, the 19 water entities submitted final water plans to the ESC for assessment, with 18 of the plans for the period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2018. G-MW submitted a final water plan for the period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2016. Each entity was required to set out in its plan:

- the expected costs of delivering water and sewerage services

- the planned capital works programs

- the forecast volumes of water to be delivered

- the level of service promised to customers

- the proposed prices that would raise sufficient revenue to recover expected costs.

The ESC's final price determinations for Water Plan 3 were released in June 2013. For all entities except G-MW and Melbourne Water, the determinations apply from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2018 or until when the ESC makes a new determination.

The determinations for G-MW and Melbourne Water cover the three-year period to 30 June 2016.

G-MW's determination could only relate to a three-year period to comply with the Water Charge (Infrastructure) Rules and pricing principles developed by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. The next price determination can cover a four-year period.

In relation to Melbourne Water the ESC confirmed the need to capitalise a portion of the desalination costs, and accepted the assessment by Melbourne Water that the capacity to do so lies in the later years of the five-year regulatory period. However, due to significant changes to the modelling assumptions that were adopted by Melbourne Water following the draft determination and given insufficient information at the time of the final determination, the ESC decided to shorten the regulatory period to enable further examination of the capitalisation of desalination costs on future prices.

1.6.2 Desalination plant refinancing

In October 2013 the Minister for Water announced that the government expects significant future savings on the Wonthaggi desalination project following an agreement to refinance the project earlier than initially planned. At the time of preparing this report the refinancing process was not complete, and the value of any savings was not known.

As the financial obligations for the desalination plant are met by Melbourne Water, the refinancing outcome will affect the financial performance and position of Melbourne Water from 2013–14 onwards.

Should the refinancing result in lower bulk water costs for Melbourne Water, the three metropolitan retail water entities expect the reduction to flow to their customers in the form of lower prices.

2 Financial reporting

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the results of the 2012–13 audits of the 19 water entities and one controlled entity. It also compares financial reporting practices in 2012–13 against better practice, legislated time lines and 2011–12 performance.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the 20 financial reports as all were given unqualified audit opinions for 2012–13. Financial reporting preparation processes were adequate for preparing accurate and timely financial reports, although opportunity for improvement exists.

Findings

- The 19 water entities met the legislated 12-week financial reporting time frame.

- Watermove finalised its financial report within 17.3 weeks of year end.

- Water entities can improve their financial reporting preparation processes by preparing shell statements, performing materiality assessments and rigorous analytical reviews and having adequate security to protect and safeguard sensitive information. These enable the early identification and resolution of financial reporting issues, thereby reducing the risk of delays and any associated additional costs.

Recommendations

That water entities:

- review their processes for capturing and calculating commitments and the training and/or briefing sessions provided to staff to improve the quality, completeness and accuracy of the information included in the financial report

- further refine their financial reporting processes by preparing shell statements, performing materiality assessments and rigorous analytical reviews, and having adequate security to protect and safeguard sensitive information.

2.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2012–13 financial reports of the 19 water entities and one controlled entity.

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured in part by the timeliness and accuracy of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report, as well as against better practice criteria.

2.2 Audit opinions issued

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing reasonable assurance that the information reported is reliable and accurate. An unqualified or clear audit opinion confirms that the financial report presents fairly the transactions and balances for the reporting period, in accordance with the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation.

A qualified audit opinion means that the financial report is materially different to the requirements of the relevant reporting framework or accounting standards, and is less reliable and useful as an accountability document.

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on the financial reports of the 20 entities for the financial year-ended 30 June 2013.

2.3 The quality of financial reporting

The timeliness and accuracy of the preparation of an entity's financial report is integral to the quality of reporting. Entities need to have well-planned and managed preparation processes to achieve cost-effective and efficient financial reporting.

Overall the financial report preparation processes of the water entities produced accurate, complete and reliable information.

2.3.1 Accuracy

The frequency and size of errors in financial reports are direct measures of the accuracy of the draft financial reports submitted to audit. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments required as a result of an audit.

Our expectation is that all entities will adjust any errors identified during an audit, other than those errors that are clearly trivial or clearly inconsequential to the financial report, as defined under the auditing standards.

The public is entitled to expect that any financial reports that bear the Auditor‑General's opinion are accurate and of the highest possible quality. Therefore all errors identified during an audit should be adjusted, other than those that are clearly trivial.

Material adjustments

When our staff detect errors in the draft financial reports they are raised with management. Material errors need to be corrected before an unqualified audit opinion can be issued.

The entity itself may also change its draft financial reports after submitting them to audit if their quality assurance procedures identify that the draft information is incorrect or incomplete.

In relation to the 2012–13 audits, 30 material financial balance adjustments were made compared to 41 in the prior year. The adjustments related mainly to fixed assets, expenses/payables, revenue/receivables and income tax. The adjustments resulted in changes to the net result and/or the net asset position of entities.

In addition to the financial balance adjustments, there were 64 disclosure errors that required adjustment in 2012–13 (23 in 2011–12).

In particular, there were 17 material disclosure adjustments relating to commitments (20 in 2011–12). This indicates that improvements can be made to the processes adopted by water entities to capture and calculate their commitments. Management at water entities should also consider providing training and/or briefing sessions to staff involved in the preparation of the commitment schedules to improve the quality, completeness and accuracy of the information included in the financial report.

Other disclosure adjustments in 2012–13 related to the completeness of accounting policies, related parties and executive officer remuneration disclosures.

All material errors were adjusted prior to the completion of the financial reports.

2.3.2 Timeliness

Timely financial reporting is key to providing accountability to stakeholders and enables informed decision-making. The later reports are produced and published after year end, the less useful they are.

The Financial Management Act 1994 requires an entity to submit its audited annual report to its minister within 12 weeks of the end of financial year. Its annual report should be tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of financial year.

The 19 water entities met the legislated time frame in 2012–13, as was the case in 2011–12. The average time taken by the 19 water entities to finalise their 2012–13 financial reports was 8.4 weeks which was the same as the prior year.

Watermove, a controlled entity of Goulburn-Murray Water (G-MW), took 39.9 weeks to finalise its 2011–12 financial report following a decision on 10 August 2012 by its directors to discontinue the company's operations. Its 2012–13 financial report was finalised within 17.3 weeks of year end. The delays did not impact the finalisation of the G-MW financial report as the transactions of Watermove during 2012–13 and its assets and liabilities were not material to the results of G-MW, and accordingly a consolidation financial report was not required.

Appendix C sets out the dates the 2012–13 financial reports were finalised.

2.3.3 Better practice

An assessment of the quality of financial reporting processes was conducted against better practice criteria, detailed in Appendix B, using the following scale:

- non-existent—process not conducted by the entity

- developing—partially encompassed in the entity's financial reporting preparation processes

- developed—entity has implemented the process, however, it is not fully effective

- better practice—entity has implemented effective and efficient processes.

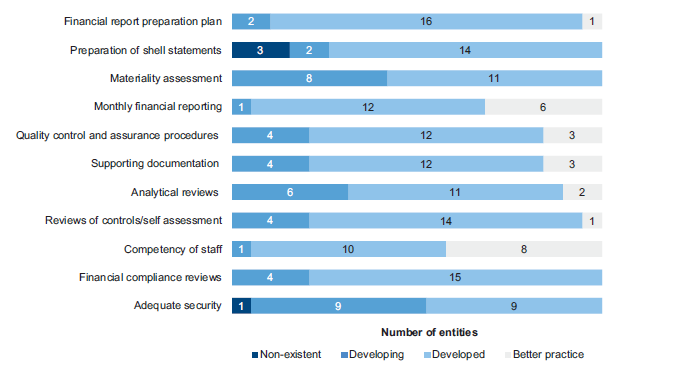

The results are summarised in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Results of assessment of financial report preparation processes against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

While most elements were developing or developed with some entities having achieved better practice, the most significant elements to be addressed by the industry are the preparation of shell statements, materiality assessment, rigorous analytical reviews and adequate security.

Adopting the better practice elements can mitigate significant delays and additional costs in the finalisation of the audit. Unaddressed these elements can jeopardise an entity's ability to meet legislated time lines and cause unnecessary cost increases due to the need for rework.

Recommendations

That water entities:

- review their processes for capturing and calculating commitments and the training and/or briefing sessions provided to staff to improve the quality, completeness and accuracy of the information included in the financial report

- further refine their financial reporting processes by preparing shell statements, performing materiality assessments and rigorous analytical reviews, and having adequate security to protect and safeguard sensitive information.

3 Performance reporting

At a glance

Background

Sixteen of the 19 water entities are required to include an audited statement of performance in their annual report. This Part covers the results of the 2012–13 audits of water entity performance reports. It also details the progress made by an industry working group to influence the indicators to be included in performance reports for 2013–14.

Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the fair presentation of all 16 performance reports as all received unqualified audit opinions for 2012–13. However, the usefulness of the reports is limited as nine of the 16 entities did not set targets for some of their indicators. This is, in part, an outcome of the disconnect between the corporate planning processes of the related water entities and the industry's performance reporting requirements with respect to the 2012–13 financial year.

An improvement in the usefulness of the reports is expected as an agreed set of key performance indicators included in water entity corporate plans for 2013–14 align with the performance reporting framework developed for 2013–14.

Findings

- Nine of 16 (10 of 16 in 2011–12) performance reports had indicators without targets.

- Commentary was not always provided for significant variations in performance.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries revisit the model performance report to assist the water entities in achieving a greater degree of compliance with the performance reporting requirements—including the explanation of variances between targets and actual performance, and between years.

- That water entities further refine their performance report preparation processes to reduce costs and achieve efficiencies in the future.

3.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the audits of the 2012–13 performance reports of 16 water entities and provides an update on work undertaken by an industry working group to influence the indicators to be included in performance reports from 2013–14.

3.2 Conclusion

Parliament can have confidence in the fair presentation of all 16 performance reports as they received unqualified audit opinions for 2012–13. However, the usefulness of the reports is limited as nine of the 16 entities did not set targets for some of their indicators. This is, in part, an outcome of the disconnect between the corporate planning processes of the related water entities and the industry's performance reporting requirements with respect to the 2012–13 financial year.

An improvement in the usefulness of the reports is expected as an agreed set of key performance indicators included in water entity corporate plans for 2013–14 align with the performance reporting framework developed for 2013–14.

3.3 Performance reporting framework

Financial Reporting Direction 27B Presentation and Reporting of Performance Information requires 16 of the 19 water entities to include an audited statement of performance in their annual report.

Directives issued pursuant to section 51 of the Financial Management Act 1994 specify the format, content, and indicators to be included in the performance report. The requirements vary across the three water sectors.

The three metropolitan retailers, City West Water, South East Water and Yarra Valley Water, are encouraged, but not required to comply with the direction. Consistent with the prior year, the three entities chose not to prepare and submit a performance report for audit for 2012–13. While they included the required financial and non-financial indicators as a separate report within their annual reports, the information was unaudited. To provide Parliament with reasonable assurance that the performance information is reliable and accurate, the entities should submit their performance reports for audit.

3.4 Audit opinions issued

Unqualified audit opinions were issued on all 16 performance reports audited for 2012–13.

Our annual attest audit on the performance report of 16 water entities is currently limited to an opinion on whether the actual results reported are presented fairly and in compliance with the legislative requirements.

3.5 The quality of performance reporting

Overall the water entities produced accurate, complete and reliable information with respect to the performance report.

3.5.1 Timeliness of reporting

Performance reports are generally prepared and finalised in conjunction with financial reports and the common time line is provided in Section 2.3.2 of this report.

Appendix C sets outs when the performance report for each entity was finalised.

3.5.2 Accuracy

In 2012–13:

- nine of 16 performance reports included indicators without targets (10 of 16 in 2011–12)

- nine of 16 water entities did not calculate significant variations correctly (five of 16 in 2011–12)

- commentary for some significant variations in performance focused on the value of the change rather than the contributing factors

- commentary was not always provided to explain significant variations between targets and actual performance or between the prior year and current year actual performance.

A particular concern was that 30 of the 166 non-financial indicators reported by the 16 entities did not have targets (31 in 2011–12). The absence of targets reduces the usefulness of performance reports because a comparison of actual performance against targets cannot be made. This is reflective of the disconnect between the corporate planning processes of the related water entities and the industry's performance reporting requirements with respect to the 2012–13 financial year.

A number of water entities stated that their lack of commentary for variances between current year and prior year performance was due to the layout of the model performance report. Our review of the model performance report indicates that it does not adequately provide for the presentation of variations between actual performance relative to the target and the prior year. Accordingly, there is an opportunity for the model performance report to be improved.

3.5.3 Better practice

In assessing the quality of the performance reports an assessment was made against better practice criteria. The framework applied in assessing the quality of the performance reports is detailed in Appendix B. The rating scale used in our assessment is consistent with that outlined in Section 2.3.3 of this report.

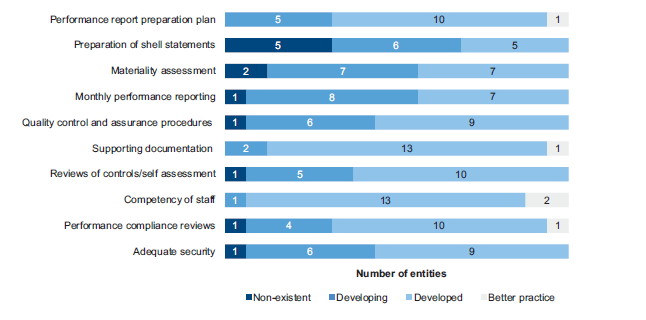

The results of our assessment are summarised in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Results of assessment of performance report preparation processes against better practice elements

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

It shows that further improvement is needed in:

- the preparation of shell statements

- materiality assessment

- monthly reporting

- quality control and assurance procedures

- adequate security.

While there was some improvement in assessment results compared to the prior year, performance reporting processes adopted by the water entities are not as mature or developed as those applied to financial reporting. Accordingly, there are greater opportunities for entities to reduce costs and achieve efficiencies in the future by addressing their performance reporting processes and practices.

3.6 Performance reporting developments and future audit approach

In our Water Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits report we indicated our intention to progress to expressing opinions on the relevance and appropriateness of the performance indicators, consistent with the Auditor-General's mandate. In that report we provided an update on progress made by the then Department of Sustainability and Environment, now known as the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), and a water industry working group in developing a contemporary framework to facilitate the inclusion of relevant and appropriate financial and non-financial indicators in the sector's future performance reports.

3.6.1 Progress in 2012–13

The intention of the water industry working group was that a contemporary performance reporting framework would apply to the first year of Water Plan 3, that being the 2013–14 financial year.

During 2012–13 the working group evaluated the relevance and appropriateness of a suite of proposed key performance indicators.

DEPI then liaised with the water industry on the proposed indicators, considered feedback on a discussion paper and finalised the indicators to be reported against from 2013–14.

The water entities were subsequently required to reflect the agreed set of key performance indicators in their 2013–14 corporate plan submissions to DEPI with an expectation that targets would be set for all indicators.

This integration and alignment of the corporate planning process with the requirements of the performance report should address one of the deficiencies noted in recent years with respect to the performance reports prepared and submitted for audit.

It is intended that audit opinions relating to the performance report will conclude on the relevance and appropriateness of the performance indicators and whether they fairly present performance, from 2013–14 onwards.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries revisit the model performance report to assist the water entities in achieving a greater degree of compliance with the performance reporting requirements—including the explanation of variances between targets and actual performance and between years.

- That water entities further refine their performance report preparation processes to reduce costs and achieve efficiencies in the future.

4 Financial results

At a glance

Background

This Part covers the financial results of the 19 water entities for the year-ended 30 June 2013.

Conclusion

The 19 water entities generated a net profit before income tax of $110 million for the year-ended 30 June 2013, a decrease of $497 million, or 82 per cent, from the prior year.

The industry also continued to access new borrowings to finance the construction of infrastructure assets and facilitate the payment of dividends.

The profitability of the 19 water entities will continue to be impacted by higher finance costs in the future, as a result of their increased borrowings to 30 June 2013.

Findings

- Finance costs increased by $329 million, or 57 per cent, compared to the prior year.

- Dividends paid or payable to the state decreased by $31 million, or 12 per cent, in 2012–13 due to the reduction in net profit.

- At 30 June 2013 the 19 water entities controlled $41.4 billion in total assets ($36.3 billion at 30 June 2012) and had total liabilities of $20.1 billion ($14.8 billion at 30 June 2012).

- Interest bearing liabilities increased by $5.4 billion, or 59 per cent, in 2012–13, due predominantly to the recognition of the desalination plant as a finance lease by Melbourne Water on 17 December 2012.

4.1 Introduction

Accrual-based financial reports enable an assessment of whether entities generate sufficient surpluses from their operations to maintain services, fund asset maintenance and repay debt. Their ability to generate surpluses is subject to the regulatory environment in which they operate, and their ability to minimise costs and maximise revenue.

An entity's financial performance is measured by its net operating result—the difference between its revenues and expenses. An entity's financial position is generally measured by reference to its net assets—the difference between its total assets and total liabilities.

4.2 Financial results

4.2.1 Financial performance

The 19 water entities are subject to the National Tax Equivalent Regime (NTER) administered by the Australian Taxation Office. The NTER is an administrative arrangement that results in government-owned enterprises paying tax to the state government rather than the Commonwealth Government.

Accordingly, we present their net results before and after income tax in this section.

Net result before income tax

The 19 water entities generated a combined net profit before income tax of $110 million for the year-ended 30 June 2013, a decrease of $497 million, or 82 per cent, from the prior year.

The overall decrease was predominantly due to Melbourne Water reporting a loss of $45.1 million compared to a profit of $372.8 million in the prior year. Its revenue was impacted by the price freeze effective from 1 July 2012, while its finance costs increased by $300 million, or 120 per cent, in 2012–13 due to the desalination plant achieving practical completion on 17 December 2012.

The water industry also experienced a 16 per cent increase in operating costs while revenue grew by 2 per cent only.

Sector performance

All four metropolitan water entities reported a lower net profit in 2012–13 than 2011–12. In addition to implementing a water price freeze from 1 July 2012, the three retailers also provided their customers with rebates totalling $98 million during the year.

The regional urban water entities, as a cohort, improved their performance, with only four of the 13 entities generating losses in 2012–13 (eight in 2011–12).

Barwon Water reported a lower net profit due predominantly to a reduction in customer capital contributions. In the prior year the private sector provided a significant contribution to the construction of the Northern Water Plant.

GWMWater's net loss was greater than the prior year due to lower revenue and higher operating costs. In 2011–12 it generated revenue due to the sale of rural water rights. During 2012–13 an agreement was reached to decommission the Wimmera Irrigation System resulting in a number of assets being fully depreciated, increasing the depreciation expense for the year. Decommissioning costs were also recognised.

The two rural water entities continued to report losses, however, the size of the losses reduced in 2012–13.

Figure 4A shows the net profit or loss before income tax for each entity for the past two years.

Figure 4A

Net profit/(loss) before income tax, by water entity

Entity |

2012–13 ($mil) |

2011–12 ($mil) |

|---|---|---|

Metropolitan sector |

||

Wholesaler |

||

Melbourne Water |

(45.1) |

372.8 |

Retailer |

||

City West Water |

48.7 |

71.7 |

South East Water |

78.3 |

129.3 |

Yarra Valley Water |

68.2 |

87.1 |

Regional urban sector |

||

Barwon Water |

28.3 |

50.6 |

Central Highlands Water |

5.5 |

(6.1) |

Coliban Water |

(19.5) |

(18.9) |

East Gippsland Water |

4.0 |

3.7 |

Gippsland Water |

4.4 |

(3.7) |

Goulburn Valley Water |

2.6 |

(6.8) |

GWMWater |

(34.8) |

(8.3) |

Lower Murray Water |

(4.4) |

(12.7) |

North East Water |

7.9 |

(2.4) |

South Gippsland Water |

(0.3) |

(1.1) |

Wannon Water |

8.6 |

4.9 |

Western Water |

4.1 |

5.2 |

Westernport Water |

1.2 |

3.0 |

Rural sector |

||

Goulburn-Murray Water |

(44.0) |

(52.2) |

Southern Rural Water |

(3.5) |

(9.0) |

Total |

110.2 |

607.1 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Seven entities delivered a loss before income tax in 2012–13 (10 in 2011–12).

Return of funds due to delays with the desalination plant

In 2011–12 Melbourne Water, City West Water, South East Water, Yarra Valley Water and Western Water collected payments from customers to cover the costs of purchasing water from the Wonthaggi desalination plant. However, due to delays in commissioning the plant, the plant was not operational and the amounts paid by customers were not needed.

From 1 July 2012 water entities began returning the payments to customers via a 12 month price freeze. At 30 June 2013, the Essential Services Commission estimated that the water entities had returned $265 million to customers. A total of $167 million was returned via the price freeze. In addition, the three metropolitan retailers and Western Water provided rebates of $98 million to eligible customers by 30 June 2013.

The Essential Services Commission commissioned an audit during the first quarter of 2013–14 to determine whether all unrequired customer payments had been returned. The audit found that as at 9 September 2013, $295.1 million had been returned to customers. A further $7.3 million is to be returned during 2013–14.

Net result after income tax

The industry reported a combined net profit after income tax of $76.9 million in 2012–13, a decrease of $360.6 million, or 83 per cent, from the prior year.

Seven entities delivered a loss after income tax in 2012–13 (10 in 2011–12).

Revenue

In 2012–13, the 19 entities generated revenue of $4.5 billion, an increase of $94 million, or 2 per cent, on the prior year. The increase was driven by a growth in customers and higher water consumption following the easing of water restrictions and a dry summer.

If revenue from transactions between Melbourne Water and the three metropolitan retailers is excluded, service and usage charges accounted for 64 per cent of the revenue generated in 2012–13.

Expenses

In 2012–13, the 19 entities incurred $4.4 billion in operating expenses, an increase of $591 million, or 16 per cent, on the prior year, predominantly because:

- finance costs increased by $329 million or 57 per cent

- depreciation and amortisation increased by $98 million or 12 per cent.

The largest expense items for the water entities in 2012–13 were finance costs, depreciation and amortisation, and employee benefits.

Melbourne Water's finance costs increased by $300 million, or 120 per cent, in 2012–13 due to the desalination plant achieving practical completion on 17 December 2012.

Dividends

The 19 entities are obliged to pay a dividend to the state if the Treasurer, after consultation with the governing board and responsible minister, makes a formal determination that they do so.

In 2012–13, dividends paid or payable by the four metropolitan water entities totalled $238 million, a decrease of $31 million, or 12 per cent, from 2011–12.

Melbourne Water's final dividend of $94.5 million for 2011–12 was recorded as a liability at 30 June 2013 as it was payable on 31 July 2013. Melbourne Water was not required to make an interim dividend payment based on its 2012–13 half-yearly result. Had dividend payments been required during 2012–13 the entity would have borrowed the funds from the Treasury Corporation of Victoria.

The three metropolitan retailers were all required to make final dividend payments for 2011–12 and interim dividend payments based on their 2012–13 half-yearly results. In light of their cash flow requirements at the time of making the payments, the three metropolitan water entities borrowed from the Treasury Corporation of Victoria.

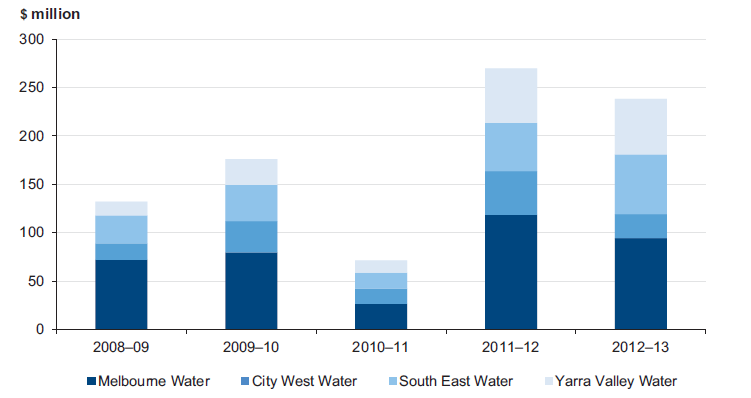

Figure 4B shows the dividends paid or payable by the four metropolitan water entities each financial year for the past five years.

Figure 4B

Dividends paid or payable by metropolitan water entities,

2008–09 to 2012–13

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

4.3 Financial position

The ability of entities to maintain their infrastructure assets depends on the adequacy of their asset and debt management policies or the level of their surpluses. Their effectiveness is reflected in the composition and rate of change of the value of their assets and liabilities over time.

4.3.1 Assets

At 30 June 2013, the 19 water entities had assets of $41.4 billion, an increase of $5.1 billion, or 14 per cent, on the prior year. Property, plant, equipment and infrastructure assets represented 95 per cent of their total assets.

A $4.7 billion increase in the value of property, plant, equipment and infrastructure assets at 30 June 2013 was predominantly driven by the recognition of the desalination plant as a leased asset by Melbourne Water upon the plant reaching practical completion.

Receivables increased by $81 million, or 14 per cent, due to greater water consumption and an increase in delays in customer payments.

4.3.2 Liabilities

At 30 June 2013, the water industry had combined liabilities of $20.1 billion, an increase of $5.3 billion, or 36 per cent, on the prior year.

Deferred tax liabilities decreased by $160 million, or 3.4 per cent, in 2012–13. In addition, interest bearing liabilities increased by $5.4 billion, or 59 per cent, during the year, due predominantly to:

- the recognition of the desalination plant as a finance lease by Melbourne Water

- new borrowings by the industry to finance the construction of infrastructure assets and to pay dividends.

A number of water entities accessed borrowings up to the limit of their Treasurer‑approved limit to take advantage of a lower financial accommodation levy (FAL).

Since 1995–96 the FAL has been applied to government business enterprises to remove the market advantage government entities may experience in borrowing, as a result of their sovereign status. It is aimed at ensuring that borrowings are valued appropriately in financing decisions for capital projects.

Until 1 July 2013, the FAL charged to water entities and paid to the Department of Treasury and Finance was capped. On 1 July 2013, the capped rate was removed and in future water entities will be charged a commercial rate for new borrowings based on their underlying credit rating.

The Department of Treasury and Finance determines the credit rating for an entity based on a desktop review and the entity can choose to have its credit rating assessed by an independent rating agency such as Moody's. The entity must pay for this themselves and make sure that the rating is based on a stand-alone basis, without the benefit of either an actual or implied government guarantee.

A number of water entities have indicated that they expect to incur a higher FAL on new borrowings going forward.

The profitability of the 19 water entities will continue to be impacted by higher finance costs in the future, as a result of their increased borrowings to 30 June 2013.

5 Financial sustainability

At a glance

Background

To be financially sustainable, entities need to be able to meet current and future expenditure as it falls due and to absorb foreseeable changes and risks without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies. This Part provides insight into the financial sustainability of the 19 water entities.

Conclusion

Analysis of the trends of financial sustainability indicators shows no significant financial improvement for the industry over the five years to 2012–13. Four entities were rated as having a high financial sustainability risk at 30 June 2013 due to the magnitude of their operating losses, which are partly due to the regulated pricing model. Servicing the growing debt and repaying the debt in the future are key challenges for the water entities.

Findings

- The timing and magnitude of price increases has a direct impact on the financial performance and position of an entity over time.

- The debt service cover ratio indicates that the ability of one metropolitan water entity to repay debt is low while another one may also encounter difficulties in repaying debt. As a result the entities will need to refinance their maturing debt.

5.1 Introduction

To be financially sustainable, entities need the capacity to meet their current and future expenditure as it falls due. They also need to absorb any foreseeable changes and financial risks that materialise, without significantly changing their revenue and expenditure policies.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both a short-term and long-term perspective. Short-term indicators relate to the ability of an entity to maintain positive operating cash flows, or the ability to generate an operating surplus in the next financial year. Long-term indicators focus on strategic issues such as the ability to fund significant asset replacement or reduce long-term debt.

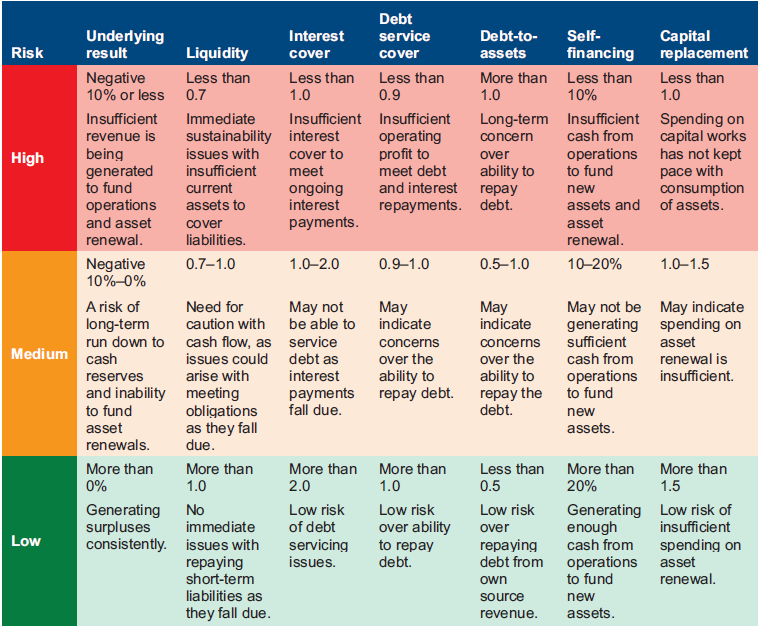

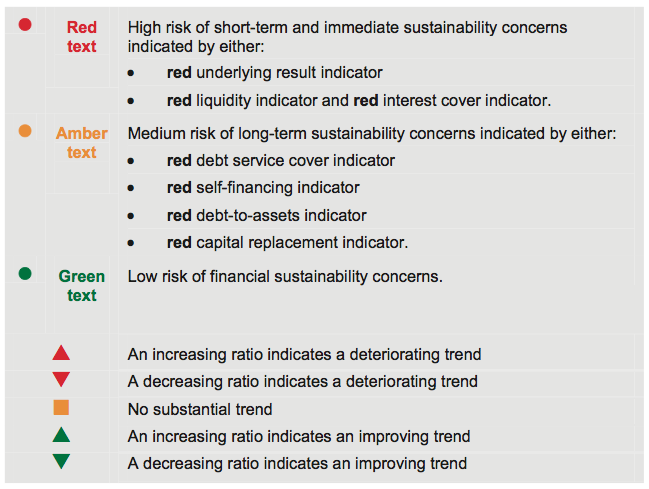

In this Part, insight is provided into the financial sustainability of water entities using the trends of seven financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period.

Appendix D describes the sustainability indicators, the risk assessment criteria used and their significance.

The financial sustainability indicators and assessments flag departures from the norm that warrant attention. However, to form a definitive view of any entity's financial sustainability requires a holistic analysis that moves beyond financial considerations to include the entity's operations and environment, and the regulatory environment in which the entity operates. These additional considerations are not examined in this report.

5.2 Financial sustainability risk assessment

5.2.1 Overall assessment

The water industry has increased its level of interest bearing liabilities, which comprises borrowings and finance lease liabilities, by $10.3 billion, or 248 per cent, over the past five years. Servicing the growing debt and repaying the debt in the future are key challenges for the water entities. The debt service cover ratio indicates that the ability of one metropolitan water entity to repay debt is low and another metropolitan water entity may encounter difficulties in repaying debt.

The profitability of the 19 water entities will continue to be impacted by higher finance costs in the future, as a result of increased borrowings. Part of the increase in borrowings during 2012–13 was due to the removal of the financial accommodation levy cap on new borrowings after 30 June 2013.

Four entities had a high financial sustainability risk rating at 30 June 2013 due to the magnitude of their operating losses, which is partly due to the regulated pricing model.

Figure 5A provides a summary of our financial sustainability risk assessment results by sector for the past two years.

Figure 5A

Financial sustainability risk assessment, by sector

|

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sector |

High |

Medium |

Low |

High |

Medium |

Low |

|

Metropolitan |

– |

2 |

2 |

– |

2 |

2 |

|

Regional urban |

4 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

6 |

5 |

|

Rural |

2 |

– |

– |

2 |

– |

– |

|

Total |

6 |

4 |

9 |

4 |

8 |

7 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

It shows that from 2011–12 to 2012–13 the greatest change in risk results occurred in the regional urban sector with a greater concentration in the medium risk category.

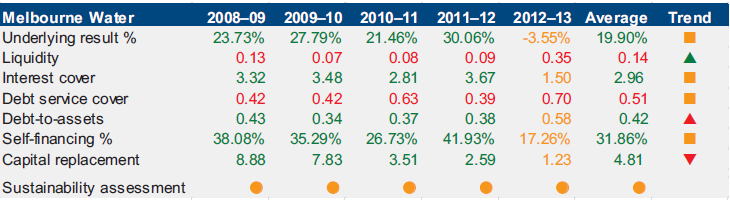

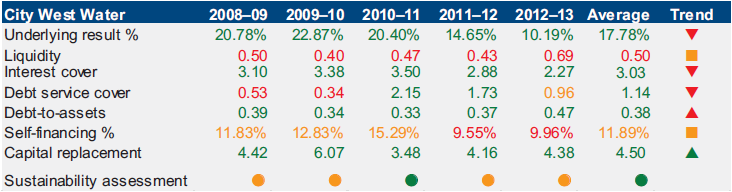

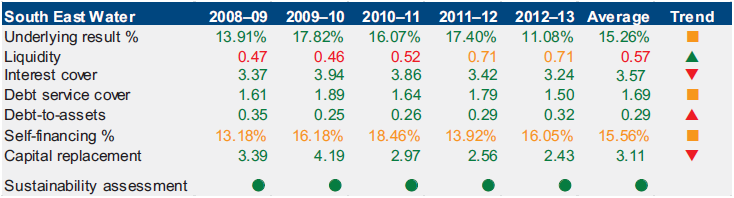

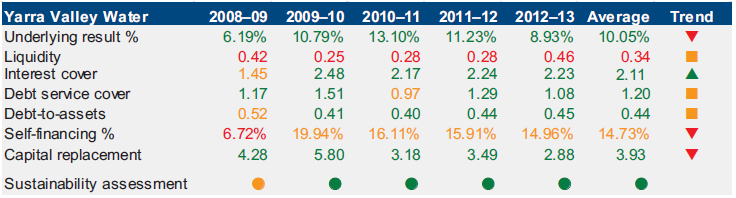

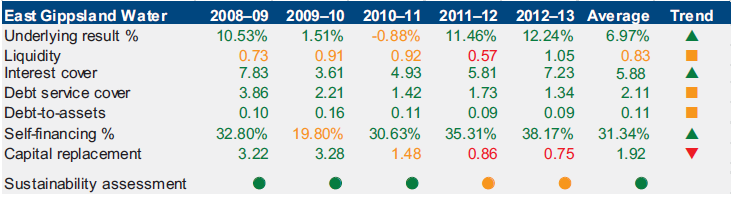

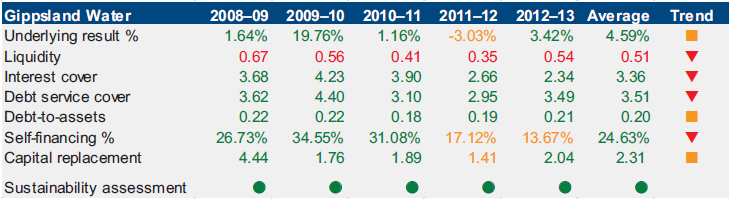

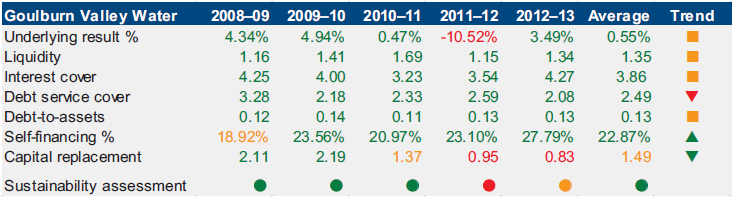

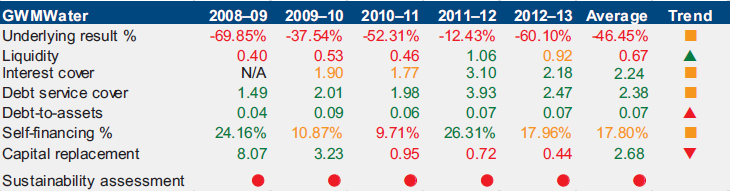

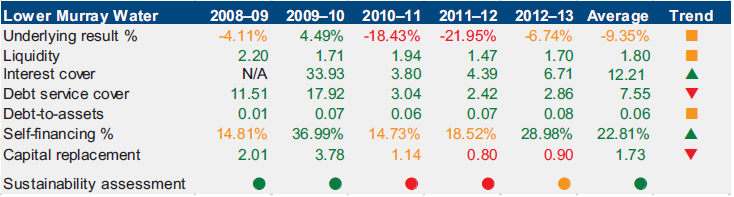

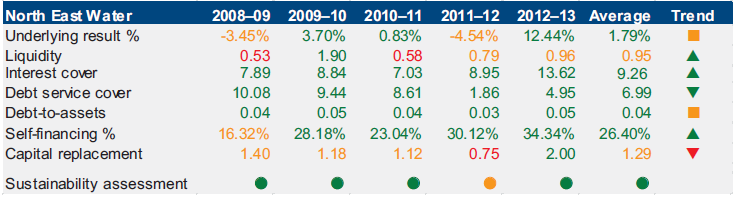

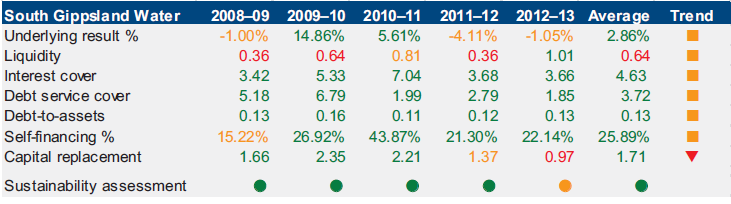

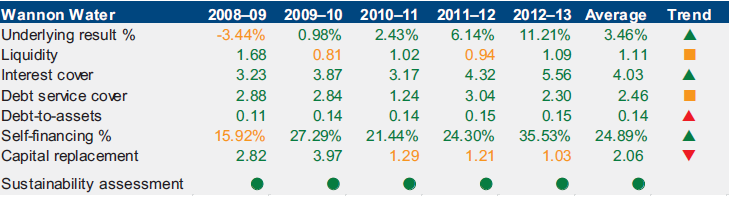

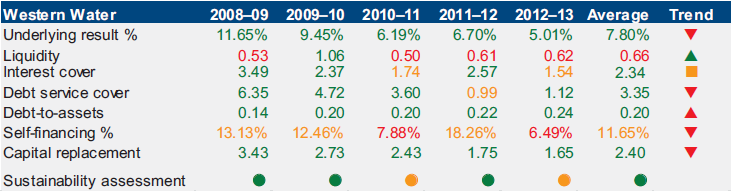

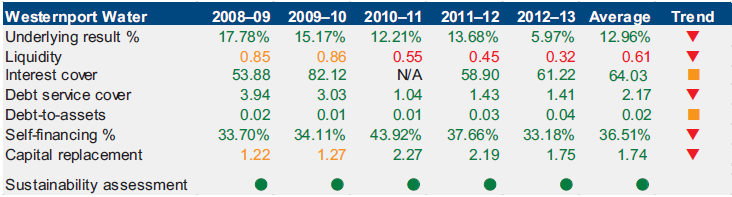

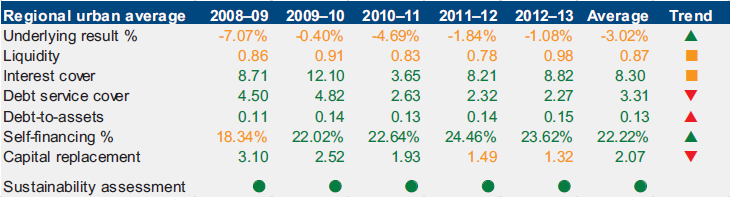

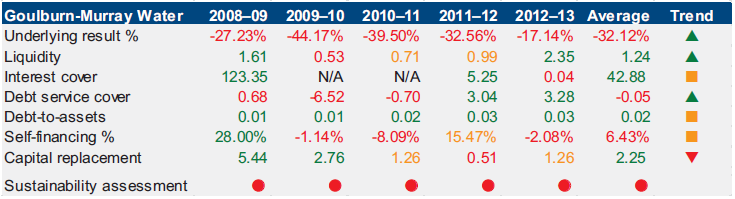

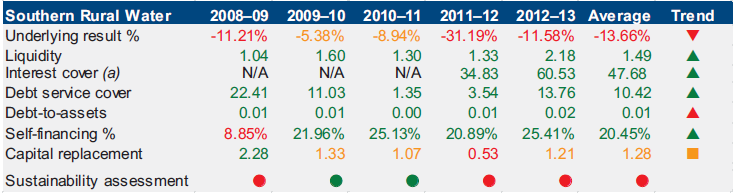

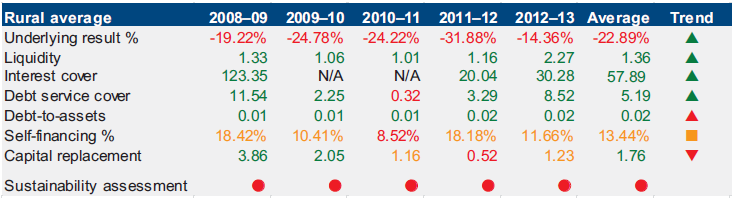

The financial sustainability results for 2008–09 to 2012–13 for each entity are provided in Appendix D.

5.2.2 Summary of trends in risk assessment over the five‑year period

When the risk assessments for each indicator are analysed they show the following trends over the five years to 2012–13:

- Underlying result—the number of entities in the high- and medium-risk categories has reduced.

- Liquidity—the number of entities in the high- and medium-risk categories has decreased indicating an improved working capital position. However, the position at 30 June 2013 was impacted by the decision of a number of entities to borrow additional funds to take advantage of lower borrowings costs.

- Interest cover—the number of entities in the medium-risk category has increased with a decrease of entities in the low-risk category.

- Debt service cover—the number of entities in the high-risk category has decreased over the five-year period with a greater number of entities in the low‑risk category.

- Debt-to-assets—the risk profile has remained steady over the five years with most entities in the low-risk category.

- Self-financing—the number of entities in the low- and high-risk categories has increased over the period.

- Capital replacement—there has been a significant shift over the five years from low risk to the medium- and high-risk categories.

In summary, the trends show no significant financial improvement for the industry over the five years to 2012–13.

Further information about the risk assessments for each indicator is presented later in this Part.

5.2.3 Analysis of trends in sustainability indicators over the five-year period

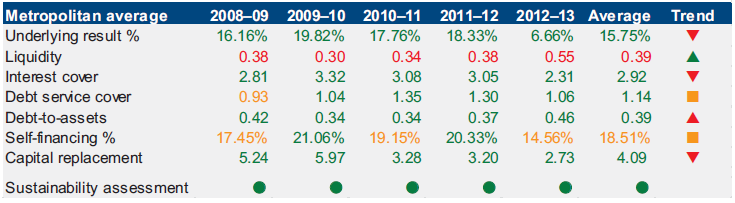

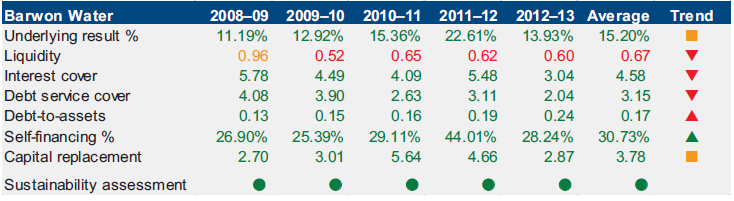

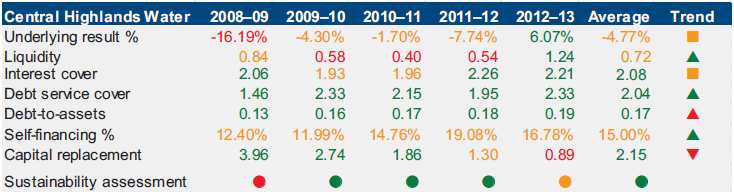

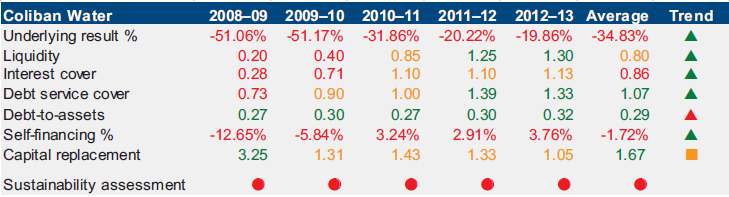

To further understand the results we analysed the five-year data for the seven indicators for the metropolitan, regional urban and rural water entities as discrete sectors. The relevant data for each sector are reproduced in Appendix D.

With respect to the metropolitan sector, four of the seven indicators experienced a declining trend over the period, but the large customer base means that entities continue to generate positive cash flows from operations and can sustain their operations.

The regional urban water entities are relatively well placed. In 2012–13 the majority of the indicators for this sector improved. For most indicators, this sector most closely matched the average result for the water industry as a whole, as discussed in Sections 5.3.1 to 5.3.7. However, the magnitude of operating losses resulted in two entities being rated as high risk.

While the rural sector entities continue to generate significant operating losses, a number of indicators are showing signs of improvement. The magnitude of the operating loss for both entities resulted in both being rated as high risk.

Impact of the water pricing model on the sustainability of regional urban and rural entities

Since 1 January 2004, the Essential Services Commission has been responsible for regulating and approving the price each water entity may charge its customers for the supply of water and the provision of sewerage services. The Essential Services Commission first approved prices for metropolitan and regional urban businesses from 1 July 2005 and for rural businesses from 1 July 2006.

Under the regulatory regime, the regulated asset value (RAV) rather than the statutory asset value is used for determining the total revenue required by an entity based on efficient costs. The RAV is reflected in the price that a water entity can charge its customers.

The opening RAV was set by the former Minister for Water as at 1 July 2004 with reference to the operating cash flow generated by the businesses at that time and subject to a range of viability and pricing outcomes based on entity forecasts. The RAV is adjusted each year by the Essential Services Commission to allow for capital investment by the businesses to the extent that the Essential Services Commission is satisfied that it is efficient expenditure.

While the opening RAVs of the metropolitan entities were set higher than their statutory asset value, the regional urban and rural entities had a RAV set lower than their statutory asset value, with the rural entities assigned a RAV of zero. As a result, a large depreciation expense not recovered through prices is carried by regional urban and rural entities.

Over time the revaluation of infrastructure assets has increased the value of assets reported in the financial reports of the 19 entities and increased the difference between RAVs and statutory asset values. This has magnified the shortfall between the water prices levied and the revenue required to meet efficient operating costs.

The difference between the RAVs and the statutory asset values is therefore a key factor in the operating losses of a number of the regional urban and rural water entities.

This issue is one of a number of matters being considered by a Water Industry Financial Sustainability (WIFS) working group established during 2011–12. The purpose of the WIFS working group is to:

- investigate the most appropriate manner of reporting, representing and communicating financial business performance for Victoria's regional water corporations

- produce a report with recommendations for consideration and implementation by the WIFS steering group.

The WIFS working group has met six times since its inception and in October 2013 considered industry responses to an issues paper circulated during May 2013. Key findings were reported to the WIFS steering group on 30 October 2013. The WIFS steering group's subsequent comments on the key findings are to be circulated to the industry.

5.3 Five-year trend analysis

This Section provides analysis and comment on the trends of the seven financial sustainability indicators over a five-year period. The indicators reflect each entity's funding and expenditure policies, and identify whether the policies are sustainable.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both a short-term and long-term perspective. The shorter-term indicators—the underlying result, liquidity and interest cover—focus on an entity's ability to maintain a positive operating cash flow and adequate cash holdings, and to generate an operating surplus over time.

The longer-term indicators—debt service cover, self-financing, debt-to-assets and capital replacement—indicate whether adequate funding is available to replace assets to maintain the quality of service delivery, and to meet community expectations and the demand for services.

5.3.1 Underlying result

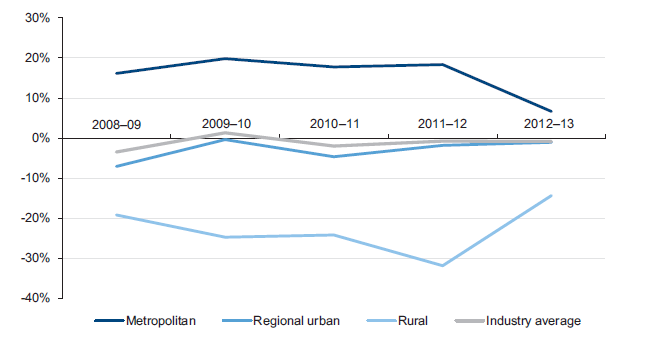

The average underlying result by sector has fluctuated over the five-year period as illustrated by Figure 5B.

Figure 5B

Average underlying result

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

For the metropolitan water entities the average underlying result was strong and relatively stable prior to 2012–13. The current year decline is an outcome of the price freeze that applied from 1 July 2012 and the recognition of operating costs associated with the desalination plant upon the plant achieving practical completion on 17 December 2012.

In contrast, the rural entities reversed a downward trend by reporting a significant improvement in 2012–13. While they continued to generate operating losses, they reduced the size of the losses compared to recent years.

The average underlying result for regional urban entities has improved over the past five years, especially in the past two years and largely reflects the industry average.

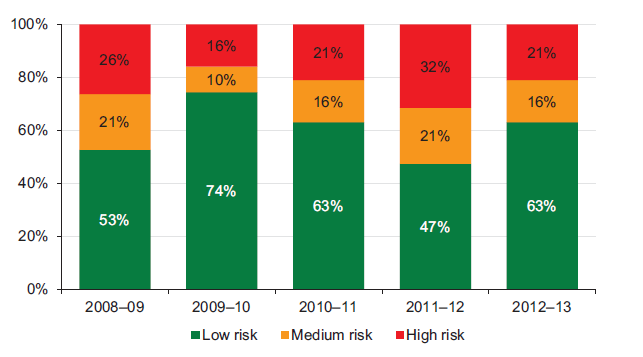

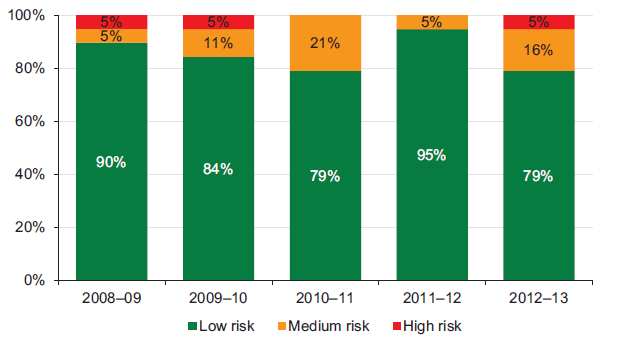

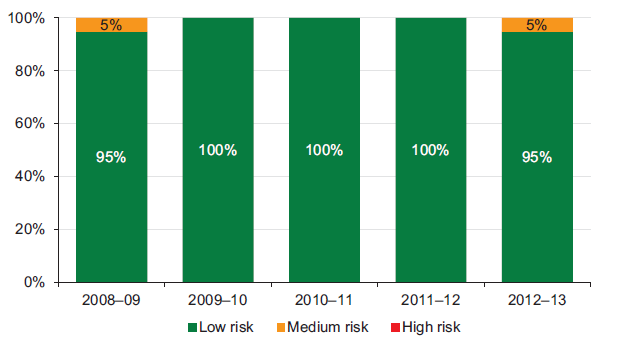

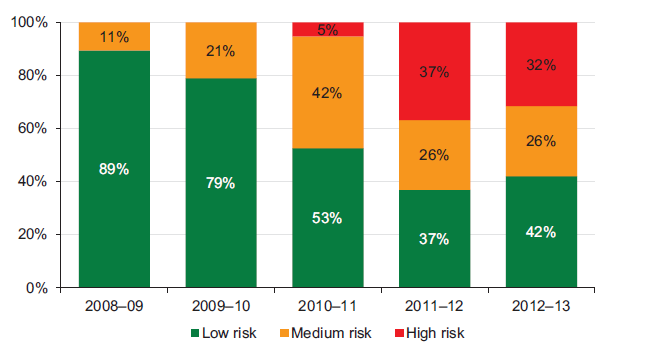

Figure 5C shows that the underlying result risk profile improved in 2012–13 with only 37 per cent of water entities (seven of 19) having an underlying result risk of high or medium, a decrease of 16 per cent from 2011–12.

Figure 5C

Underlying result risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The improvement in 2012–13 reflects the impact of:

- revenue growth, due to higher prices for regional urban and rural water entities

- a long, hot and dry summer, resulting in higher water consumption

- easing of water restrictions.

This was offset by:

- higher finance costs

- higher depreciation expenses

- higher employee benefit expenses.

The higher finance costs were driven by substantial increases in borrowings across the sector from 1 July 2008 to finance the construction of infrastructure. The desalination plant also resulted in Melbourne Water reporting a $300 million, or 120 per cent, increase in its finance costs in 2012–13.

5.3.2 Liquidity

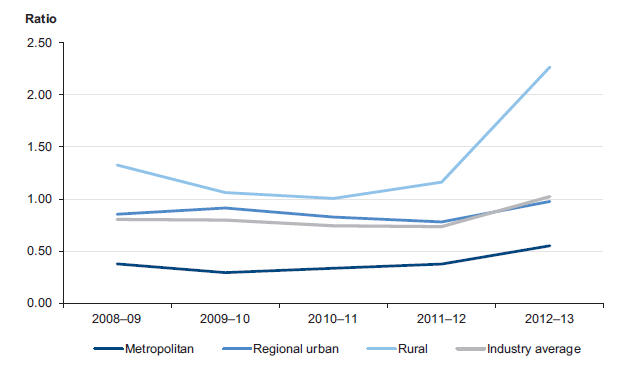

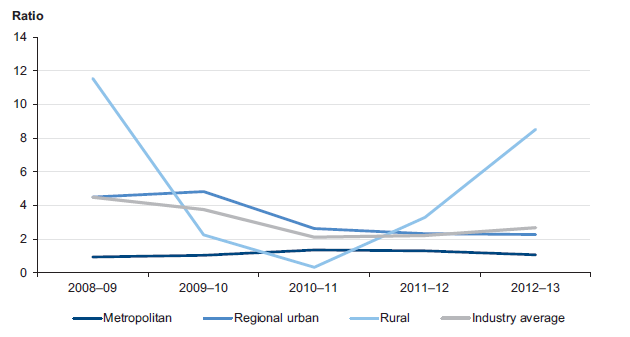

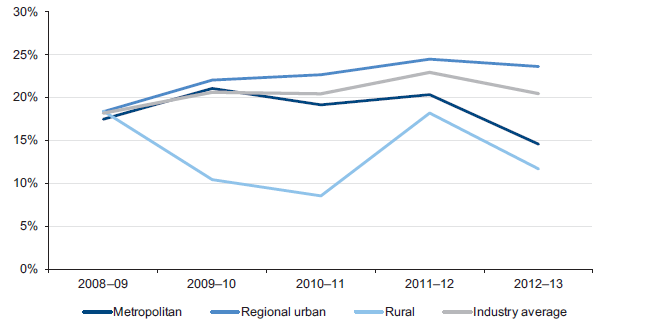

Figure 5D shows that the average liquidity of the water entities has improved over the five years, most significantly in the rural sector.

Figure 5D

Average liquidity ratio

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The substantial increase for rural water entities in 2012–13 is predominantly a consequence of one entity accessing new borrowings at balance date to take advantage of a lower financial accommodation levy. This strategy was also adopted by a number of entities in the other two sectors. The resulting increase in cash reserves was offset by new long-term borrowings classified as non-current liabilities at balance date.

The 19 entities source their borrowings from the Treasury Corporation of Victoria. Entities have approval to refinance their maturing debt and in recent years have done so. While entities have approval to refinance maturing debt, they also need to generate sufficient cash flows from operations to:

- service the increasing interest charges as debt levels increase and the variable interest rates rise

- repay the growing debt in the long term.

For some entities higher water consumption also positively affected the revenue generated and available cash reserves in 2012–13.

The average liquidity ratio for regional urban entities largely reflects the industry average over the five-year period.

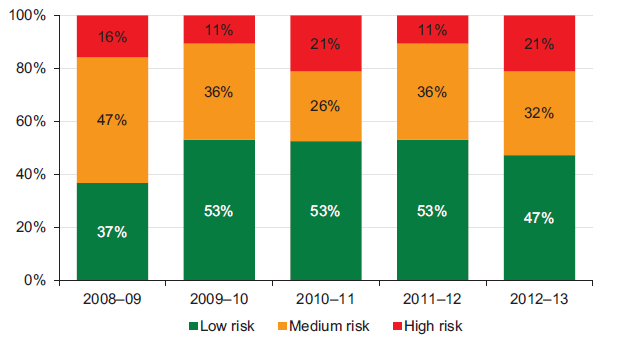

Figure 5E shows that at 30 June 2013, 53 per cent of water entities (10 of 19) had a liquidity risk of high or medium, that is, their current liabilities exceeded current assets.

Figure 5E

Liquidity risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The percentage of entities with a high liquidity risk decreased by 16 per cent in 2012–13. However, this was due to entities accessing new borrowings just prior to 30 June 2013, rather than improving their liquidity as a result of improved financial performance.

5.3.3 Interest cover

Figure 5F shows that the average interest cover varied by sector across the five years.

Figure 5F

Average interest cover ratio

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The metropolitan water entities maintained an adequate level of interest cover over the period. While their debt levels and finance costs have increased significantly, they continue to generate positive cash flows from their operations annually. Due to the desalination plant and impact of the price freeze, Melbourne Water's ability to meet its ongoing interest payments and to service debt deteriorated at 30 June 2013.

Six of the 13 regional urban water entities experienced a deteriorating level of interest cover in 2012–13. Finance costs rose because of additional borrowings, however, profits and operating cash inflows remained stable or improved marginally. Despite this, the level of interest cover was still adequate for the majority at 30 June 2013.

The trend for the rural entities shows a level of volatility that reflects the small number of entities in the cohort (two entities). The financial performance and position of the two entities need to be considered individually as the results vary widely. At 30 June 2013, Southern Rural Water had adequate interest cover whereas Goulburn-Murray Water's (G-MW's) interest cover was insufficient to meet its interest payments.

G-MW assumed responsibility for the Connections Project, previously known as the Food Bowl Modernisation Project, on 1 July 2012. While the project is being funded by both the state and Commonwealth, in 2012–13 actual cash payments were greater than the level of project funding received. This contributed to G-MW reporting a negative operating cash flow for the year.

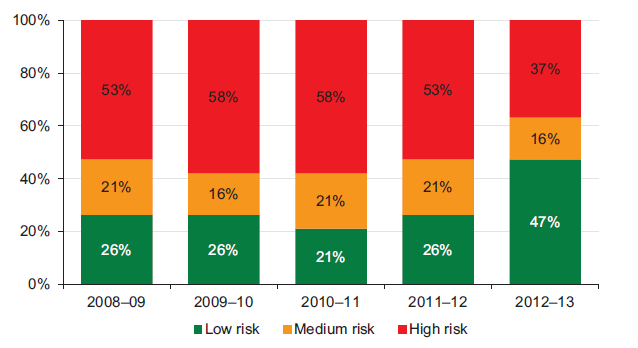

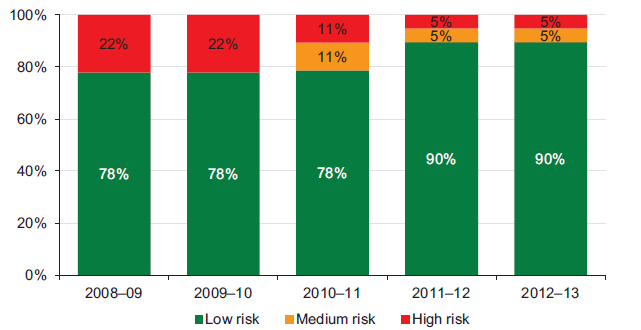

Figure 5G indicates that the interest cover risk was low for 79 per cent of water entities (15 of 19) at 30 June 2013, a decrease of 16 per cent from 2011–12. However, caution is needed as the level of interest cover from year to year can be influenced by the timing of operating cash receipts and payments.

Figure 5G

Interest cover risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The number of entities in the high- and medium-risk categories increased between 2011–12 and 2012–13. The deterioration in the past year is reflective of the growth in borrowings and higher finance costs.

5.3.4 Debt service cover

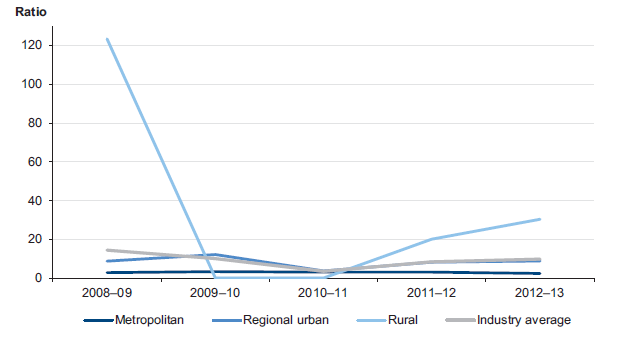

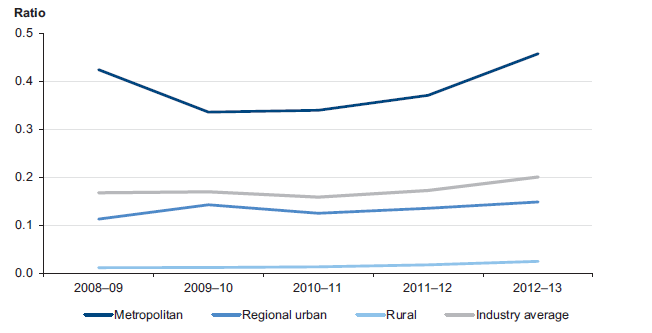

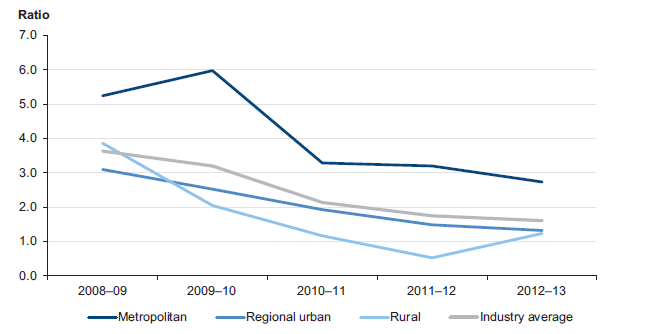

The water entities increased their interest bearing liabilities, comprising borrowings and finance lease liabilities, by $10.3 billion, or 248 per cent, over the past five years.

Figure 5H shows that the ability for regional urban water entities to repay debt from operating profits has decreased over the five years. In contrast, over the past three years, the rural water entities' ability to repay debt from operating profits improved.

Figure 5H

Debt service cover

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The debt service cover for the metropolitan sector has remained consistent over the period, although both City West Water and Melbourne Water had ratios of less than one at 30 June 2013.

The rural sector shows an improvement in the debt service cover from 2010–11 to 2012–13. The more recent increase was an outcome of drier weather conditions which enabled the entities to increase their variable water charges.

Figure 5I shows the number of entities with a low debt service cover risk has improved over the five-year period.

Figure 5I

Debt service cover risk assessment

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

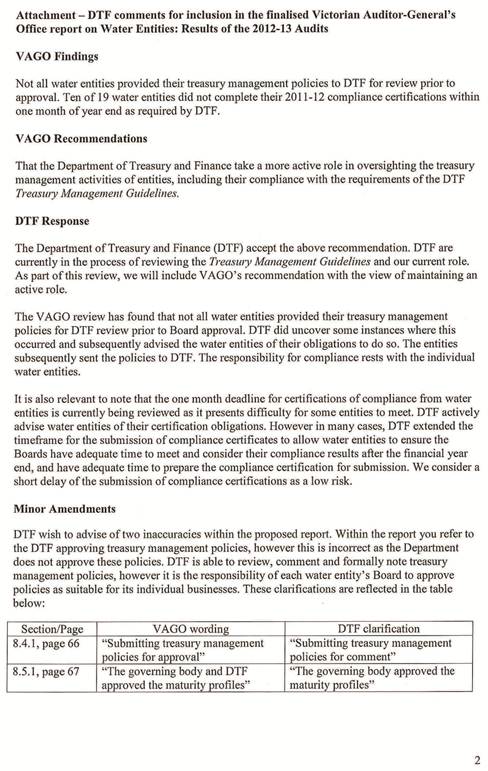

5.3.5 Debt-to-assets