Recovering and Reprocessing Resources from Waste

Overview

In 2016–17, Victorians generated and managed nearly 12.9 million tonnes of waste. Metropolitan Melbourne accounted for around 80 per cent of this. Sustainability Victoria (SV) estimates that Victorians recovered 67 per cent of the 12.9 million tonnes for recycling and sent the remaining 33 per cent to landfill.

Community participation in the recycling process is a vital part of the state’s waste system. To invest their time in separating bottles, papers and other recyclables, Victorians need confidence that these materials are properly recycled. The Chinese government's decision to significantly restrict its importation of recyclables under the Chinese Sword policy has significantly affected the recycling industry and led to a significant decline in Victorian waste exports.

This audit examined whether responsible agencies are providing strategic direction, support and effective regulation in order to maximise the recovery and reprocessing of resources from Victoria's waste streams.

The audit included the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Environment Protection Authority (EPA), the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group (MWRRG), SV, Banyule City Council and the City of Monash Council.

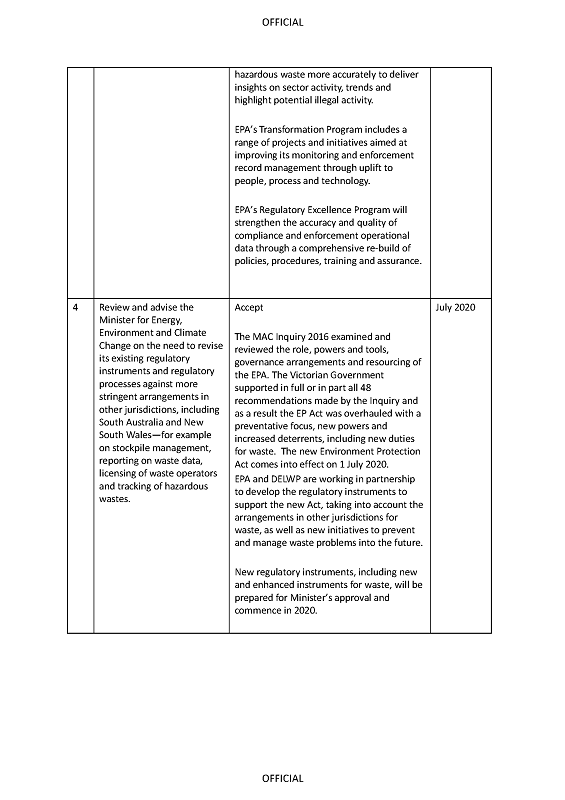

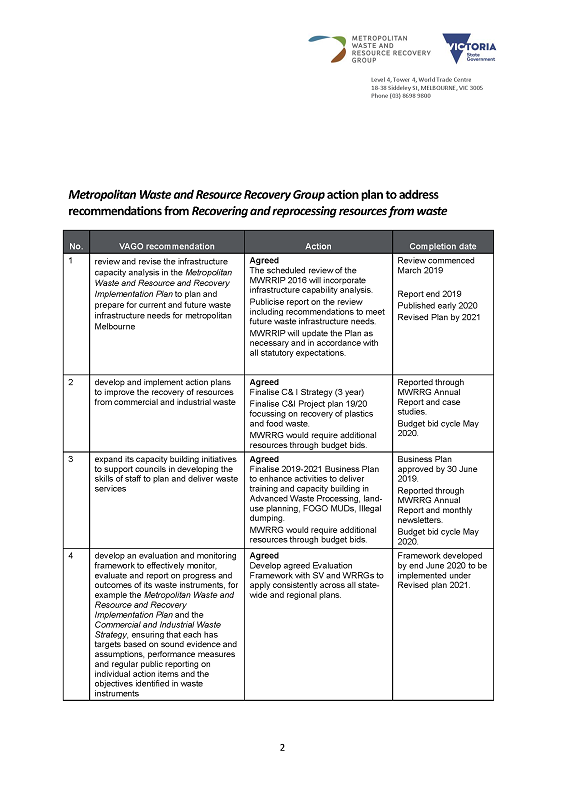

We made six recommendations for DELWP, eight for SV, four for EPA, and four for MWRRG.

Transmittal letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2019

PP No 37, Session 2018–19

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Recovering and Reprocessing Resources from Waste.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

5 June 2019

Acronyms & Abbreviations

Acronyms

| C&D | construction and demolition |

| C&I | commercial and industrial |

| CRWM | combustible recyclable and waste materials |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| EPA | Environment Protection Authority |

| FOGO | food organics and garden organics |

| GFV | Getting Full Value |

| LHFW | Love Food Hate Waste |

| MDS | Victorian Market Development Strategy for Recovered Resources |

| MILL | Municipal and Industrial Landfill Levy |

| MoU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| MSW | municipal solid waste |

| MUD | multi-unit development |

| MWRRG | Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group |

| MWRRIP | Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Implementation Plan |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| PAN | pollution abatement notice |

| RISP | Recycling Industry Strategic Plan |

| RSS | ResourceSmart Schools |

| RWRRIP | regional waste and resource recovery implementation plan |

| SA | South Australia |

| SV | Sustainability Victoria |

| SWRRIP | Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan |

| TZW | Towards Zero Waste |

| TZWMP | Towards Zero Waste Management Plan 2019–23 |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VLGAWSR | Victorian Local Government Annual Waste Services Report |

| VORRS | Victorian Organics Resource Recovery Strategy |

| VRIAR | Victorian Recycling Industry Annual Water Services Report |

| WES | Victorian Waste Education Strategy |

| WRR PCB | Waste and Resource Recovery Project Control Board |

| WRRG | waste and resource recovery group |

| WRRIP | waste and resource recovery implementation plan |

| WtE | waste to energy |

Abbreviations

| Banyule Council | Banyule City Council |

| C&I Strategy | Metropolitan C&I Waste and Resource Recovery Strategy |

| CRWM PIA | Management and storage of CRWM Policy Impact Assessment |

| CRWM Policy | 2018 Waste Management Policy (Combustible Recyclable and Waste Materials) |

| e-waste | electronic waste |

| e-waste PIA | Managing e-waste in Victoria Policy Impact Assessment |

| e-waste Policy | Waste Management Policy (e-waste) |

| MAC Review | Ministerial Advisory Committee Review on Waste and Resource Recovery Governance Reform |

| Monash Council | City of Monash Council |

| MUDs toolkit | Improving resource recovery in multi-unit developments toolkit |

| the Act | The Environment Protection Act 1970 |

| the Framework | Victorian Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Planning Framework |

| the Guideline | Data and Reporting Guideline for Waste Management Facilities |

| the Minister | Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change |

| the Standards | Better Apartment Design Standards |

| the Taskforce | Resource Recovery Facilities Audit Taskforce |

Audit overview

Sustainability Victoria (SV) estimates from available data that in 2016–17 Victorians:

- generated nearly 12.9 million tonnes of waste—with metropolitan Melbourne accounting for around 80 per cent of this

- recovered 67 per cent of the waste generated for recycling and sent the remaining 33 per cent to landfills across the state.

Victorians recover a range of recyclable material from three waste streams:

- municipal solid waste (MSW)

- commercial and industrial (C&I) waste

- construction and demolition (C&D) waste.

Recyclable materials include food organics and garden organics (FOGO), plastics, paper and cardboard, aluminium cans, rubber (including tyres), electronic waste (e-waste), bricks and other construction materials.

The Environment Protection Act 1970 (the Act) is the primary legislation dealing with the state's waste management and resource recovery. It introduces a waste hierarchy, with waste avoidance at the top, representing the most important mechanism to reduce waste, followed by re-use, and then recycling.

The Chinese government's decision to substantially limit its importation of recyclables (the Chinese Sword Policy) led to a significant decline in Australian waste exports. This has increased costs for councils that were previously able to sell their recyclables, but now must pay to have them removed.

Given the importance of waste management to the Victorian community and the current pressures on the system, this audit examined whether responsible agencies are maximising the recovery and reprocessing of resources from Victoria's waste streams.

The audit included Banyule City Council (Banyule Council), City of Monash Council (Monash Council), the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Victorian Environment Protection Authority (EPA), Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group (MWRRG), and SV.

Conclusion

Victorian agencies responsible for managing the waste sector are not responding strategically to waste and resource recovery issues. As a result, they are not minimising Victoria's need for landfill nor maximising the recovery and reprocessing of waste resources—recyclables. A significant amount of the waste that Victorians send to landfill could be recycled or reprocessed, and some recyclables that Victorians segregate for recycling eventually end up in landfills.

DELWP has not fulfilled its leadership role to ensure that the state operates under an overarching waste policy. Without such a policy since 2014, Victorian waste management agencies have been operating in an uncertain environment and are unable to effectively prioritise their limited time and resources.

|

In a circular economy, materials, energy, and other resources are used productively for as long as possible to retain value, maximise productivity, minimise greenhouse gas emissions, and reduce waste and pollution. |

The lack of an overarching statewide policy deprives responsible government agencies and their stakeholders of a clear and definitive direction for waste management, which means that government agencies' responses to waste issues have been ad hoc and reactive. DELWP advise that it is developing a policy—which will be in line with circular economy principles—however, it is not due until 2020.

In the absence of an overarching waste policy, relevant agencies have also not been able to effectively plan for sufficient infrastructure and markets to manage the state's waste. Recent significant restrictions in the waste export market has brought this issue into sharp focus. This risk was not without early warning. DELWP and SV did not identify signals as early as 2013 that China was changing its approach and that the state's heavy reliance on exporting recyclables, particularly plastic and paper, left it vulnerable. In July 2018, DELWP released the Recycling Industry Strategic Plan (RISP). However, the RISP does not include a definitive plan for new infrastructure to address emerging issues. Without clear state-level plans for how to manage recyclables in this new environment, stockpiles will likely continue to grow and pose unnecessary risks, and waste to landfills will continue to rise.

EPA has not effectively monitored and addressed the growth of inappropriately managed stockpiles across the state, which pose health and fire risks to the community and the environment. As a number of toxic fires in waste facility sites demonstrate, the need for greater oversight of waste operators is evident. However, since the significant Coolaroo fire in July 2017, EPA has increased its oversight of the state's resource recovery facilities.

These issues—lack of action to minimise waste, to invest in infrastructure, and closely regulate the sector—have occurred while the Sustainability Fund, a fund set up under the Act to support best practices in waste management, had $511.3 million as at 30 June 2018.

Findings

Leadership for waste management

No overarching statewide policy

Victoria has not had a statewide waste policy since 2014. This means that responsible agencies have directed their efforts and resources on waste management activities for over five years without the clear direction that an overarching policy provides. To address the gap, DELWP is currently developing the Circular Economy Policy, which it expects to complete by 2020.

Unclear statewide guidance

Despite changes arising from the recommendations of our 2011 report, Municipal Solid Waste Management, and the 2013 Ministerial Advisory Committee Review on Waste and Resource Recovery Governance Reform (MAC Review), roles and responsibilities in the waste and resource recovery sector remain unclear.

DELWP clarified state agency roles in its 2019 update to the 2015 Waste and Resource Recovery Portfolio Collaboration Framework. This document captures the roles of DELWP, SV, EPA and the waste resource and recovery groups (WRRG). However, DELWP has failed to clearly communicate this—and councils and industry continue to be confused about state agency roles.

There are six waste strategies intended to guide waste and resource recovery in metropolitan Melbourne. These identify 23 goals or objectives, 23 strategic directions, and 103 actions. Collectively, they do not provide clear and coherent guidance.

In the absence of a statewide policy, some stakeholders mistakenly believe that the Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan (SWRRIP) is the statewide waste policy. In fact, the SWRRIP is one of four key strategies and plans—the others are the Victorian Organics Resource Recovery Strategy (VORRS), the Victorian Market Development Strategy for Recovered Resources (MDS) and the Victorian Waste Education Strategy (WES)—meant to underpin the implementation of the statewide policy.

Limited implementation of statewide strategies

SV is not effectively implementing its four strategies that guide the waste and resource recovery sector in Victoria to ensure waste to landfill is minimised because the SWRRIP, VORRS, MDS and WES:

- include many vague actions that do not provide specific guidance on how to achieve identified objectives or clearly plan which projects and activities must occur before an action is complete

- do not have targets, adequate performance measures or specify frequency of reporting.

Three years since their publication, SV does not have a clear plan to implement all of the actions in the VORRS, MDS and WES. SV's limited implementation of the VORRS is a missed opportunity to improve the recovery rate of organic material by 2020. In contrast, the government allocated funding to fully implement the 2018 RISP to stabilise the recycling sector and develop markets for recycled materials. It is accompanied by a more detailed implementation plan that articulates the expected outcomes or targets, time lines and lead agencies. DELWP reports on its implementation to the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change (the Minister).

DELWP, SV and MWRRG report some key outputs from their various strategies publicly in their annual reports. Despite this, they are not clearly, transparently, and publicly reporting on the progress of the individual actions, overall objectives and outcomes of their strategies in a way that enables industry and the community to track their progress.

Since 2017–18, the government has allocated SV $785 000 from the Sustainability Fund to deliver the VORRS; $8.31 million to deliver the WES and related education programs; and $6.42 million to deliver the MDS. SV advised us that the allocations are not sufficient to fully implement all the actions outlined in these strategies. However, SV did not provide detailed advice to government that specified and costed the remaining action items when seeking funding to deliver them. In addition, the government has not allocated MWRRG additional ongoing funding to implement expanded responsibilities for C&I and C&D waste.

We note that as at 30 June 2018, the balance of the Sustainability Fund remained at $511.3 million. As per legislation, one of the purposes of this funding is for best practices in waste management. The revenue that contributed to this fund balance has been previously recognised in the state's bottom line. Any future expenditure from the fund accordingly, will act to reduce the bottom line.

Gaps in statewide waste management instruments

|

A multi-unit development is when more than one dwelling is built on a single lot, including more than one house, unit, or townhouse. |

Current waste management instruments—relevant plans, strategies, policies and regulations—have significant gaps. They do not give policy direction or guidance on waste avoidance, hazardous waste management, multi-unit developments (MUD), waste to energy (WtE), or C&I waste.

Responsible agencies are taking limited action at the statewide, regional and local levels to avoid generating waste. While the current waste strategies and plans refer to the waste hierarchy and mention waste avoidance, none focus directly on improving waste avoidance practices. As a result, responsible agencies do not give avoidance actions enough preference or attention when managing waste.

The SWRRIP does not include planning for hazardous waste infrastructure. SV acknowledges this gap and plans to include this in the next iteration of the SWRRIP due in 2023. However, given issues arising from the inappropriate storage and management of hazardous waste, the government allocated $2.2 million in DELWP's 2018–19 budget to better manage the disposal of hazardous waste and to develop a hazardous waste policy.

DELWP, SV, MWRRG and Victorian councils are not taking strong enough action to ensure new and existing MUDs offer recycling collection services. Action is needed to make sure that as the number of MUDs increases there is not an overall decrease in recovery rates.

Council kerbside waste collection is not available to most existing MUDs, and private operators are engaged to collect waste from these sites. While councils can influence how much space new MUDs allocate for waste infrastructure through the planning process, they currently do not require new or existing MUDs that are serviced by commercial operators to offer comingled and organics recycling services. Most MUDs have only one waste collection service—for landfill.

|

WtE technologies consist of any waste treatment process that creates energy in the form of electricity, heat or transport fuels from a waste source. |

There is currently no WtE policy to guide government agencies and potential investors on what WtE technologies are acceptable and how they should implement them in Victoria. This is contributing to limited investment in new technologies.

Responsible agencies are taking limited action at the statewide, regional and local levels to increase diversion of C&I waste from landfill, and instead focus their efforts on MSW. Sending C&I waste to landfills remains a relatively low‑cost option for business. As a result, many businesses choose to send recyclables to landfill rather than recycling them.

Council waste plans

Banyule Council and Monash Council are ably fulfilling their roles in delivering waste and resource recovery services to their communities. Both councils have managed to provide continued waste services despite the challenges brought about by the Chinese Sword Policy. This is due in part to the continued ability of their contracted resource recovery facility operator—both councils use the same operator—to process councils' recyclables.

Councils' waste plans include targets, action plans and performance indicators, and both audited councils are collaborating with MWRRG to achieve cost efficiencies in their waste service contracts, including organics processing, collection of recyclables and landfill services. Both councils are also taking steps to ensure that their waste services to their communities remain undisrupted.

Understanding Victoria's waste data

Inaccurate and incomplete waste data and reporting

SV's 2016–17 Victorian Local Government Annual Waste Services Report (VLGAWSR), initially published in September 2018, stated that nearly all recyclables segregated by Victorians are recycled, as did the 2013–14 and 2015–16 VLGAWSRs. This is not the case. While nearly all recyclables are sent to recovery facilities for sorting, there is currently no data on how much of this is recycled. During the audit, SV acknowledged that it did not use the term 'recycled' correctly in this context, and corrected the online version of the 2016–17 VLGAWSR report accordingly.

While waste data collection is a shared responsibility among SV, EPA, councils and WRRGs, SV is responsible for its statewide oversight, coordination and reporting.

The current incomplete and unreliable Victorian waste data limits the government's ability to understand the nature and volume of the state's waste, what becomes of collected recyclables, and where they end up. Waste data quality issues also affect the government's ability to make well informed planning and investment decisions to address current and future risks and needs.

The incompleteness and unreliability of current Victorian waste data also means that DELWP and SV have limited understanding of whether the unchanged statewide recovery rate of 67 per cent from 2012–13 to 2016–17 is accurate, and whether it is due to improved resource recovery, or unfavourable reasons such as unaccounted waste stockpiling or illegal dumping.

Currently reported state waste data:

- excludes information about the movement of recovered recyclable and waste materials or of illegally dumped materials (data not collected)

- excludes information on the nature and extent of stockpiles—permitted or otherwise—across the state (data not collected)

- excludes information on the level of market demand for Victorian recyclables (data not collected)

- excludes waste sent to landfills that are not subject to the landfill levy (data not collected)

- excludes hazardous waste sent to landfill—data is collected by EPA but not included in SV's annual waste data reporting

- are estimates—not based on actual data—for the MSW, C&I and C&D waste streams, including the reported tonnage for recovered resources such as paper and cardboard, plastics, glass and steel

- for many categories, is collected by SV through voluntary surveys of councils and waste recovery and reprocessing operators, and as such is incomplete and not necessarily accurate

- is collected by councils and waste operators in variable ways, including counts of trucks and visual estimates

- is subject to very limited quality assurance by SV, which focuses on checking for significant changes in data from year to year.

SV has been aware of data quality issues for at least 15 years, particularly regarding the reliability and completeness of MSW data. In response, SV has developed the Waste Data Governance Framework and established a waste data portal for sharing waste information across relevant agencies.

However, while SV has enabled the sharing of some waste data and improved its collaboration with responsible agencies and councils, it has made little progress to address identified data quality issues. SV advised us that a lack of regulatory measures means it cannot resolve identified data quality issues. If this is the case, then SV should advise government of the necessary regulatory changes to enable this to occur.

Identifying and managing risks

Market demand for recyclables—government's response

To date, waste management in Victoria has focused on separating and recovering recyclables from waste otherwise destined for landfills. The push to recover recyclables, however, has not always been matched by market demand for recycled products. Without accessible and competitive end markets, the number and size of stockpiles will continue to grow, and recyclables will eventually end up in landfills.

DELWP, as the lead Victorian agency with portfolio responsibility for the waste sector, could have more effectively intervened to minimise the adverse consequences of China's significant import restrictions. It did not provide strong, timely advice to government on the risks associated with Victoria's dependence on overseas markets for recycling. It was not until January 2018—when the significant export restrictions had already started—that DELWP and SV started to develop a list of possible interventions and support councils to develop contingency plans.

In February 2018, the government provided temporary relief funding of $12 million to assist councils with increased waste collection costs resulting from the Chinese Sword Policy. In July 2018, the government released the RISP that lists, as its first goal, the stabilisation of the state's recycling system.

On 14 February 2019, EPA ordered a resource recovery operator to stop receiving collected recyclables at its Coolaroo and Laverton facilities because its significant waste stockpiles at these sites posed an unacceptable fire risk. The operator services 34 Victorian councils, including 18 metropolitan councils, and recovers more than half of the state's kerbside recyclables.

After EPA's actions, DELWP worked with relevant agencies to identify contingency measures for the collected recyclables. DELWP advised that, given the quantities involved, preventing recyclables from going to landfill was not a viable option. DELWP documentation suggests that nearly 500 tonnes of collected recyclables were sent to landfills for every day that the two facility sites were closed.

In many ways, China's heightened regulation under its Green Fence Policy in 2013 foreshadowed its subsequent announcements to significantly restrict its waste importation. Consequently, DELWP could have more proactively monitored earlier developments in China to better anticipate potential impacts on the state's waste.

|

Collective or joint procurement is the process of developing and managing multi-council contracts for waste management and resource recovery services and facilities. |

The councils included in this audit—Monash Council and Banyule Council—have service contracts with another resource recovery operator and were not affected by EPA's actions against the sanctioned waste operator. Both councils are proactively working to ensure the continued collection of their recyclables, including coordinating with MWRRG to participate in the latter's collective recycling procurement contract that is expected to be available in 2020.

In April 2018, the Chinese government announced that it would stop importing paper and plastic wastes effective 1 January 2019—regardless of contamination levels. While China did not completely enforce this announcement by January 2019, many other Asian countries including Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam also declared waste import restrictions.

SV is the state's lead agency tasked to achieve the government's goal to develop markets for recycled materials. To date, however, SV's efforts have largely targeted new and expanded uses for products that use recovered glass, tyres and recycled concrete. While SV has made progress in this regard, including working on the approval of revised product specifications, more could be done to target new markets for more problematic recyclables, such as plastics, where only limited opportunities have been identified to date.

Insufficient infrastructure

Further risks for the sector exist given the inadequacy of waste infrastructure planning. Neither SV's SWRRIP nor MWRRG's Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Implementation Plan (MWRRIP) provide for future infrastructure, and neither consider the impacts of the closure of international export markets. Based on the capacity analysis prepared by WRRGs in 2014 and 2015, the SWRRIP states that there is sufficient resource recovery and landfill infrastructure to service Victoria until 2025. However, this analysis included export markets and was based on SV waste data, of which quality and completeness is significantly limited.

It has become clear that Victoria needs more local reprocessing facilities to convert recovered materials into products that can be used again, or to energy. However, SV's 2018 update of the SWRRIP did not consider the impacts of the significant consequences of the Chinese Sword Policy on Victoria's waste infrastructure needs despite China's announcement in July 2017.

According to the SWRRIP and the MWRRIP, Melbourne is at risk of inadequate landfill capacity by 2025 if appeals against approved planning permits or works approvals are successful. If the landfill capacity of a metropolitan Melbourne landfill cannot be increased, a new landfill of similar capacity will need to be scheduled by 2021 and commissioned by 2026.

MWRRG is currently working with DELWP, SV and south-east metropolitan councils to reduce their reliance on landfills by establishing new and more efficient resource reprocessing infrastructure. This may include the use of WtE technology (discussed in Part 4). MWRRG advised us that it is working with south-east metropolitan councils to establish advanced waste processing to avoid shortfalls in Melbourne's landfill capacity by 2026.

MWRRG advised us that it has commenced a review of its infrastructure capacity through a review of the MWRRIP, taking into consideration export market changes. Further, MWRRG is working to collectively tender for recyclables collection services on behalf of metropolitan councils, to be available by 2020, to reduce current reliance on the export of recyclable materials and attract local options.

Waste stockpiles

|

Combustible recyclable and waste materials include paper, cardboard, plastic, rubber, textile, organic, metals or other combustible material which is considered waste. |

EPA has not effectively regulated the waste industry. It has been slow to act—firstly with combustible recyclable and waste materials (CRWM) in recovery facilities—and more recently with hazardous waste stockpiles. In both instances, EPA intervened only at the point of crisis. The significant fire at Coolaroo in July 2017 spurred EPA to take more serious action.

As waste materials degrade over time, many stockpiled resources end up in landfills. Stockpiles, either waiting for markets or illegally dumped, in time turn into pseudo-landfills. The extent of waste stockpiles across Victoria shows that they are not isolated instances of poor waste regulation—it has become a large‑scale and systemic statewide problem.

EPA has since begun clearing some of the state's most problematic waste stockpiles. However, there is little assurance that its expenditure for these clean-ups will be fully recovered from responsible parties.

Stockpiles at resource recovery facilities

In response to the significant fire at Coolaroo in July 2017, the government established the Resource Recovery Facilities Audit Taskforce (the Taskforce) to identify and address waste stockpiles across the state. The Taskforce identified 831 sites—of which five were classified as posing extreme risk and a further 209 as high risk.

Many of the identified sites are located very close to residential areas. The December 2017 Taskforce report noted that inadequately managed stockpiles of combustible recyclables pose serious and unacceptable risks to the Victorian community and environment.

Hazardous waste in metropolitan Melbourne warehouses

Following the August 2018 West Footscray fire, EPA identified warehouses illegally filled with drums containing significant amounts of highly flammable hazardous chemicals. EPA regulates the movement of hazardous wastes, and none of these sites—located near residential areas—hold EPA permits to store them.

On 5 April 2019 a fire broke out at another hazardous waste storage site in metropolitan Melbourne. In contrast to the previously identified hazardous waste storage sites, the operator of this site has an EPA licence to process toxic chemical waste. EPA suspended its license the month before the fire for holding more waste than it was permitted to store, and not adequately storing it—in breach of its licence conditions.

Affected Victorian communities are understandably concerned about EPA's ability to effectively regulate the management of hazardous wastes and waste stockpiles. Given the frequency of fires, EPA needs to prioritise addressing illegal and non-compliant behaviour in the hazardous waste sector. The Victorian community has the right to expect that where recovery facilities and the storage of waste pose health and environmental risks, EPA will promptly identify these risks, work with relevant agencies, and apply the full force of the law.

Stricter regulations in other jurisdictions

Strict and effective regulations in other Australian jurisdictions meant that it was cheaper to transport waste materials to Victoria than to dispose of them to licensed sites in either South Australia (SA) or New South Wales (NSW). This contributed to the state's growing stockpiles—particularly recovered recyclables (prior to 2018) and end-of-life waste tyres (prior to 2014).

Enforcement provisions of the Act

The Act has provisions against improper waste management, which carries substantial penalties. EPA's more frequent use of these provisions could have served as a strong disincentive to irresponsible and illegal practices that have resulted in large-scale waste stockpiles across Victoria. However, EPA advised that the post-harm or post-damage focus of these provisions made it difficult to successfully prosecute cases against waste operators.

Because of perceived limitations of the Act's provisions to address current improper waste management practices, the government worked to give EPA new legislation that focuses on a general environmental duty—with a preventative focus—to protect human health and the environment. EPA advised that these 2018 amendments to the Act, which will take effect in 2020, give it more power to better address waste issues.

Changing community behaviour

Disposal of waste to landfill

According to available data, SV estimates that Victorians send 33 per cent of their waste to landfill. A 2015 bin audit by a metropolitan Melbourne council estimates that 65 per cent of what is sent to landfill could be viably recovered and reprocessed. This means that there is significant opportunity to reduce what is currently being sent to landfill.

Waste avoidance

Nothing within the current waste instruments focuses directly on improving waste avoidance practices. As a result, DELWP, SV, MWRRG and councils focus their efforts on managing waste already in the system and do not give avoidance actions sufficient preference or attention. This is not consistent with the waste hierarchy identified in the Act, which gives waste avoidance the highest priority.

Waste education

Many Victorians still do not fully understand what is and what is not recyclable due to the lack of a consistent, sustained statewide approach to education. Agencies run disparate short-term education campaigns, and this is compounded by inconsistent council recycling practices across the state.

SV, MWRRG and councils have delivered waste education using several education programs and communication campaigns that have raised some awareness of waste and resource recovery issues. However, they have delivered these campaigns inefficiently because they do not adequately leverage materials already developed by other agencies.

There is an opportunity for closer collaboration between the tiers of government in designing and delivering waste education programs, where councils and WRRGs distribute statewide messages locally and regionally. The model SV used for its e-waste education campaign reflects this approach. It developed education materials at a statewide level and distributed them to councils.

Managing organics and e-waste

Organic waste makes up to 35 per cent of the waste sent to Victorian landfills. Responsible agencies are missing a key opportunity to decrease waste going to landfill by not placing enough focus on increasing organic waste recovery.

SV, MWRRG and both audited councils identify organic waste as the key material stream that should be targeted for recovery. Despite this, DELWP, SV and MWRRG have not taken strong enough action to address this. While government has provided limited funding for activities to increase the recycling of organics, DELWP and SV did not provide detailed enough advice to government specifying and costing out actions when seeking funding.

In contrast, the government has taken a proactive approach when it comes to e‑waste, reportedly one of the fastest-growing material streams going to landfill. In 2014, the government committed to banning e-waste to reduce harm to the environment and human health and increase the recovery of valuable resources contained within it. However, DELWP did not complete the Waste Management Policy (e-waste) (e-waste Policy) until four years after the announcement.

DELWP advised us it took significant time to develop and finalise the policy as it consulted with affected stakeholders to develop a package of support measures that would assist the policy's implementation. Councils were reluctant to act on e-waste until details of the policy requirements were finalised. This meant that from the time the e-waste Policy was finalised in 2018 to the time the ban takes effect in July 2019, councils had limited time to sufficiently prepare in terms of:

- establishing recovery infrastructure to comply with the e-waste Policy

- setting up contracts with e-waste collectors

- educating the community about the proper management of e-waste.

As a result, councils are not fully prepared for the ban when it comes into force on 1 July 2019.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, in collaboration with waste portfolio agencies including Sustainability Victoria, the Victorian Environment Protection Authority, the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group, regional waste and resource recovery groups, and councils:

1. include in its overarching statewide waste policy:

- strategies for waste avoidance (see Sections 2.5 and 5.3)

- specific actions to achieve identified objectives, noting responsible agencies and time lines (see Sections 2.3 and 2.4)

- an evaluation framework specifying performance measures and targets linked to objectives (see Sections 2.3 and 2.4)

- a plan to publicly report on progress of implementation and the achievement of outcomes against identified objectives (see Sections 2.3 and 2.4)

2. study, assess and advise the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change on ways to improve waste and resource recovery outcomes including:

- reducing the sector's reliance on international markets for recyclable materials, such as encouraging establishment of local reprocessing and remanufacturing facilities, and improving recycling behaviours (see Sections 4.2 and 4.3)

- effective market interventions for recovered resources, for example, government procurement targets for recyclable materials (see Section 4.2)

- possible levers to improve recycling of resources from waste, which may include expanded product stewardship arrangements, package labelling on products, and a container deposit scheme (see Section 4.2)

- price signals such as changes to the landfill levy rate and the possible impact of this on recovery rates (see Section 4.3)

3. develop and publish a document that states the roles and responsibilities—including responsibilities indicated in disparate waste policies and strategies—of all portfolio agencies, local councils and other relevant entities involved in waste management and regulation and communicate this to councils and waste operators (see Section 2.2)

4. support the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group in its capacity-building initiatives to train councils' staff and waste management and resource recovery groups' staff so that they can effectively deliver their respective waste management roles and responsibilities, including for collective procurement, land-use planning, multi-unit developments' waste management, and food and garden organics (see Section 5.5)

5. strengthen the Planning Scheme to ensure multi-unit developments have waste management plans designed and approved in accordance with the Better Practice Guide for Waste Management and Recycling in Multi-unit Developments (see Section 2.5)

6. advise the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change on options to divert organic waste from landfill, including:

- maximising the collection of organic waste from commercial and industrial establishments (see Sections 5.2 and 5.6)

- the required resources to support the rollout of food and garden organics kerbside collections for all local governments (see Sections 5.5 and 5.6).

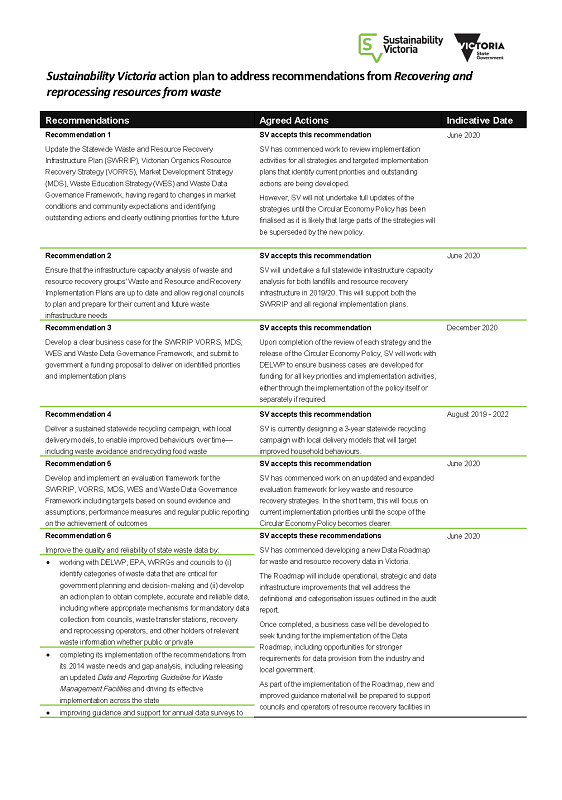

We recommend that Sustainability Victoria:

7. update the Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan, Victorian Organics Resource Recovery Strategy, 10-year Victorian Market Development for Recovered Resources Strategy , Victorian waste education strategy and Waste Data Governance Framework, having regard to changes in market conditions and community expectations and identifying outstanding actions and clearly outlining priorities for the future (see Section 2.4)

8. ensure that the infrastructure capacity analysis of waste and resource recovery groups' waste and resource and recovery implementation plans are up to date and allow regional councils to plan and prepare for their current and future waste infrastructure needs (see Section 4.3)

9. develop a clear business case for the Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan, Victorian Organics Resource Recovery Strategy, 10-year Victorian Market Development for Recovered Resources Strategy, Victorian waste education strategy and Waste Data Governance Framework, and submit to government a funding proposal to deliver on identified priorities and implementation plans (see Section 2.4)

10. deliver a sustained statewide recycling campaign, with local delivery models, to enable improved behaviours over time—including waste avoidance and recycling food waste (see Section 5.4)

11. develop and implement an evaluation framework for the Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan, Victorian Organics Resource Recovery Strategy, 10-year Victorian Market Development for Recovered Resources Strategy, Victorian waste education strategy and Waste Data Governance Framework including targets based on sound evidence and assumptions, performance measures and regular public reporting on the achievement of outcomes (see Sections 2.3 and 2.4)

12. improve the quality and reliability of state waste data by:

- working with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, the Victorian Environment Protection Authority, waste and resource recovery groups and councils to (i) identify categories of waste data that are critical for government planning and decision-making; and (ii) develop an action plan to obtain complete, accurate and reliable data that includes, where appropriate, mechanisms for mandatory data collection from councils, waste transfer stations, recovery and reprocessing operators, and other holders of relevant waste information whether public or private (see Sections 3.2 and 3.3)

- completing its implementation of the recommendations from its 2014 waste needs and gap analysis, including releasing an updated Data and Reporting Guideline for Waste Management Facilities and driving its effective implementation across the state (see Section 3.4)

- improving guidance and support for annual data surveys to help councils and waste operators in providing more accurate and reliable waste data (see Sections 3.3. and 3.4)

- reporting clearly on waste data in its Victorian Local Government Waste Services Report and Victorian Recycling Industry Annual Report by:

- ensuring waste terminologies and definitions are consistent, including a glossary of terms for each report, and ensuring their appropriate and consistent use across the two reports (see Sections 3.2 and 3.3)

- clearly articulating the nature of data being presented and where appropriate clarifying the difference between the data reported in both reports (see Sections 3.2 and 3.3)

13. work with the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group and regional waste and resource recovery groups to provide better support to councils in rolling out food and garden organics collection services (see Section 5.6)

14. work with the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group, councils and regional waste and resource recovery groups to establish a working group or community of practice to better collaborate and reduce inefficiencies in waste education (see Section 5.4).

We recommend that the Victorian Environment Protection Authority:

15. determine and prioritise key non-compliance and emerging waste risks for targeted action by:

- compiling and continually updating a publicly available inventory on waste stockpiles/dumps/storage of all waste operators—licensed, permitted or otherwise—detailing location, type of waste or resource, extent (tonnage/volume), responsible parties, action taken and outcomes (see Section 4.4)

- developing and implementing a prioritised action plan to clean-up or require the clean-up of identified waste risks (see Section 4.4)

16. prepare and implement a prioritised action plan to oversight the waste activities of licensed and permitted waste operators to ensure compliance with their licence or permit conditions, including on the quantity and manner of storage of waste and resources (see Section 4.4)

17. improve its monitoring and enforcement record management to allow a clear assessment of the effectiveness of its actions (see Section 4.4)

18. review and advise the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change on the need to revise its existing regulatory instruments and regulatory processes against more stringent arrangements in other jurisdictions, including South Australia and New South Wales—for example on stockpile management, reporting on waste data, licensing of waste operators and tracking of hazardous wastes (see Section 4.4).

We recommend that the Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group:

19. review and revise the infrastructure capacity analysis in the Metropolitan Waste and Resource and Recovery Implementation Plan to plan and prepare for current and future waste infrastructure needs for metropolitan Melbourne (see Section 4.3)

20. develop and implement action plans to improve the recovery of resources from commercial and industrial waste (see Section 2.5)

21. expand its capacity-building initiatives to support councils in developing the skills of staff to plan and deliver waste services (see Section 5.5)

22. develop an evaluation and monitoring framework to effectively monitor, evaluate and report on progress and outcomes of its waste instruments, for example, the Metropolitan Waste and Resource and Recovery Implementation Plan and the Commercial and Industrial Waste Strategy, ensuring that each has targets based on sound evidence and assumptions, performance measures, and regular public reporting on individual action items and the objectives identified in waste instruments (see Section 2.3).

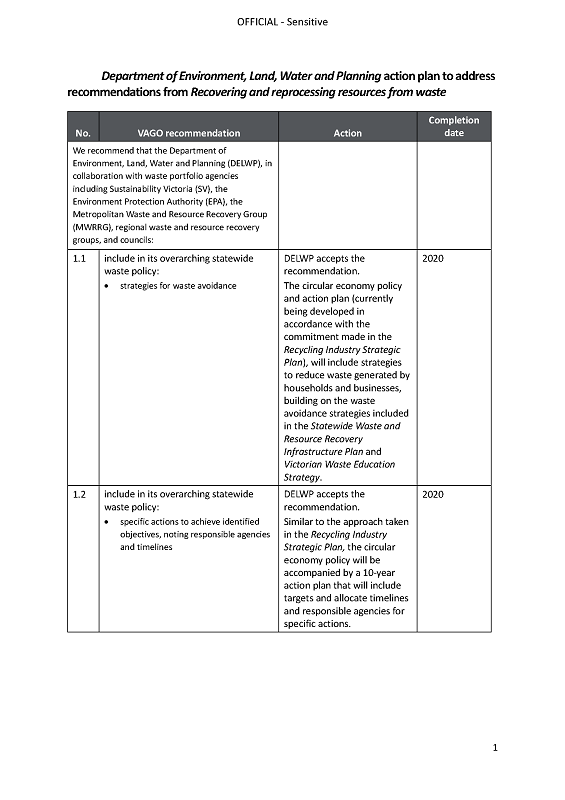

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with Banyule Council, Monash Council, DELWP, EPA, MWRRG and SV and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

All four audited agencies have accepted the recommendations addressed to them. The audit did not address recommendations to the two audited councils. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

1 Audit context

Victorian residents and businesses threw away some 12.9 million tonnes of waste in 2016–17. SV predicts that this waste will reach 20 million tonnes by 2046. Metropolitan Melbourne accounts for around 80 per cent of total state waste.

Councils and private waste operators manage rubbish and discarded materials through a network of collection and transportation services, and recovery, reprocessing and landfill facilities. Recovery is the separation of recyclables from waste destined for landfills. The government's role is to provide strategic direction, support and, where necessary, effective regulation.

Community participation in the recycling process is an important component of the state's waste system. To invest their time in separating bottles, papers and other recyclables, Victorians need confidence that these materials are properly recycled.

For the purposes of this report, 'waste' refers to all materials that consumers and business have discarded.

1.1 Waste streams and material types

Waste streams

Waste is typically sourced from:

- MSW—household and some commercial waste collected at the kerbside by councils or their contractors

- C&I waste—commercial and industrial buildings collected mostly by private waste operators

- C&D waste—construction sites, collected by private operators.

Waste generated from these streams include glass, paper and cardboard, metal, plastic, tyres, FOGO, e-waste, and general rubbish. Some waste materials are hazardous in nature, including asbestos and chemical wastes from industries. EPA regulates the handling, storage, transport and disposal of these materials through the Environment Protection (Industrial Waste Resource) Regulations 2009.

Waste material types

Plastics

SV broadly groups plastic as either rigid or flexible. Rigid plastics are widely used in products such as bottles, containers, toys, pipes, and window frames. Flexible plastics are used for packaging film, plastic bags, shrink wrap, builder's film, and agricultural products such as silage wrap and wheat bags.

In 2016–17, the state recovered 131 000 tonnes of plastic—more than half of which came from MSW.

Paper and cardboard

The main categories of value for reprocessing in Victoria are:

- cardboard and paper used for packaging (boxes)

- newspapers

- magazines

- printing and writing paper.

These items are used to manufacture recycled paper, packaging material and boxes. Material exported overseas is usually baled, compacted mixed paper.

According to available 2016–17 data, the Victorian waste and resource recovery system managed approximately two million tonnes of paper and cardboard. Of this, Victoria recovers 1.5 million tonnes, or approximately 75 per cent, with the remaining disposed of in landfill.

Tyres

A tyre becomes a waste tyre when it can no longer be used for its original purpose. Every year, Australians generate 56 million waste tyres.

If not properly managed, waste tyres can cause significant environmental and public health risks. Whole tyres are flammable and pose a considerable fire hazard when stored together or stockpiled. If ignited, large volumes of waste tyres are difficult to extinguish and can have severe impacts on the air, soil, and water due to pollution. This can result in high economic costs and liabilities.

Organic waste

Organic waste refers to any material that comes from a natural and biodegradable substance. It can be solid material such as timber and woody garden waste, food, or liquid waste such as grease trap waste or dairy effluent. It includes food waste from households, supermarkets, manufacturing, restaurants, and agricultural and effluent waste.

According to available data, organic waste makes up to 35 per cent of the total solid waste sent to landfill in Victoria. If not managed properly it has the potential to impact negatively on the community, environment and public health.

Available data indicates that food waste has the lowest recovery rate of all materials. According to the SWRRIP, the system currently manages nearly a million tonnes of food waste but in 2015–16 only 10 per cent was recovered:

- 67 per cent from the MSW sector (4 per cent recovered)

- 33 per cent from the C&I sector (23 per cent recovered)

- less than 1 per cent from the C&D sector.

E-waste

E-waste includes televisions, computers, mobile phones, kitchen appliances and white goods. It is any product that uses an electric current to run. These items can contain valuable materials, such as gold, copper and platinum. E‑waste can also contain highly hazardous materials.

E-waste makes up only 1 per cent of waste currently going to landfill; however, it is one of the fastest-growing waste streams in Australia. E-waste from televisions and computers alone is expected to grow by over 60 per cent, or 85 000 tonnes, by 2024.

In late 2014, the government committed to banning e-waste from landfill to reduce harm to the environment and human health, and increase recovery of the resources in e-waste.

1.2 Waste infrastructure

The state's waste sector comprises operators that collect, sort, recycle, recover and dispose to landfill waste materials generated through the three waste streams. Figure 1A shows the infrastructure used to manage this waste.

Figure 1A

Four major groups of waste and resource recovery infrastructure

Source: VAGO, from the SWRRIP.

According to SV, as at 1 June 2017 the state has more than 630 sorting, recycling and landfill infrastructure sites. Figure 1B provides a breakdown of these sites by region.

Figure 1B

Number of waste infrastructures across Victoria

|

Region |

Sorting or recovery facilities |

Recycling or reprocessing facilities |

Landfill or disposal infrastructure |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Metro Melbourne |

69 |

69 |

18 |

156 |

|

Barwon South West |

52 |

21 |

6 |

79 |

|

Gippsland |

97 |

21 |

10 |

128 |

|

Goulburn Valley |

41 |

22 |

5 |

68 |

|

Grampians Central |

74 |

13 |

16 |

103 |

|

Loddon Mallee |

47 |

8 |

13 |

68 |

|

North East |

21 |

10 |

4 |

35 |

|

Total |

401 |

164 |

72 |

637 |

Source: VAGO, from the SWRRIP.

1.3 Legislation and policy

All Australian environment ministers endorsed the 2018 National Waste Policy: Less waste, more resources, which lays out the country's waste management and resource recovery direction to 2030.

Environment Protection Act 1970

The Act, which established EPA, is also the primary legislation that deals with Victorian waste management and resource recovery. It establishes a waste management hierarchy, which sets out an order of preference for how waste should be managed to help achieve the best possible environmental outcomes. This is shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

The waste hierarchy

Source: VAGO, from the Act, s.1I

Victorian Waste and Resource Recovery Planning Framework

The 2014 amendments to the Act established the Victorian Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Planning Framework (the Framework). The Framework's objective is to ensure long‑term strategic planning for waste and resource recovery infrastructure at state and regional levels through integrating needs, policy and statewide coordination. The Framework consists of:

- the SWRRIP

- regional waste and resource recovery implementation plans (RWRRIP)

- relevant ministerial guidelines.

Victorian waste policy

In 2013 the then Victorian Government released Getting Full Value (GFV) as the overarching statewide waste policy. To deliver on its objectives, GFV mandated the development of the SWRRIP, RWRRIPs and several other waste strategic plans.

The current government did not endorse GFV as the state's waste policy when it came to office in 2014 and has not released a new policy. In 2018–19 the government approved a $9.02 million funding allocation for DELWP to develop a whole-of-government waste policy that incorporates circular economy principles. DELWP advised us that this will be released in 2020.

Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan

Under the Act, SV must prepare the SWRRIP to provide strategic direction for the development and use of waste and resource recovery infrastructure for 30 years. SV published the first SWRRIP in 2015 and republished it in 2018 to incorporate the priorities and infrastructure analyses of the WRRIPs of the seven WRRGs.

The Act requires SV to review the SWRRIP at least once every five years. This must include an analysis and description of current and future waste and resource recovery sources, levels, and trends.

Regional Waste and Resource Recovery Implementation Plans

RWRRIPs set out how the resource recovery infrastructure needs of the WRRGs will be met over at least a 10-year period. They align with the SWRRIP and describe how statewide infrastructure needs will be implemented at a regional level.

RWRRIPs must include an analysis and description of current and future waste and resource recovery sources, levels, and trends. RWRRIPs are also required to include an infrastructure schedule for their region and a description of how the long-term directions of the SWRRIP will be implemented locally.

1.4 Roles and responsibilities

Maximising the recovery and reprocessing of resources from waste relies on goodwill from the community and the effective collaboration of the state government, responsible agencies, and councils. Clarity in roles and responsibilities is critical for effective and coordinated planning and implementation of the state's waste programs and activities.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

DELWP is primarily responsible for:

- policy development

- leadership, coordination, and oversight of the waste portfolio

- working with other state and federal government departments

- oversight of the Sustainability Fund, including financial management and advice on expenditure.

Sustainability Victoria

According to the Sustainability Victoria Act 2005 and relevant waste strategies and plans, SV is responsible for:

- planning and facilitating the statewide management of waste

- developing and implementing strategies to foster sustainable markets for recovered resources and recycled materials

- developing tools to measure and report on government waste targets

- promoting waste avoidance, waste reduction and recovery, re-use, recycling of resources and best practices in waste management across the state

- preparing the SWRRIP and assisting in the preparation of RWRRIPs

- developing and implementing strategies, frameworks, projects, and programs to promote and facilitate the sustainable use of resources

- providing investment facilitation expertise and funding infrastructure development

- delivering statewide waste education and behaviour change campaigns

- developing and implementing a data management governance framework, including developing standards and guidelines to ensure consistency, accuracy and timeliness of the data collected to support decision-making and infrastructure planning.

Victorian Environment Protection Authority

EPA is responsible for controlling pollution from waste through the development and enforcement of regulations and environmental standards. EPA also manages the collection of funds related to environmental regulation and enforcement, including the landfill levy.

Regional waste and resource recovery groups

Regional WRRGs, including MWRRG, are responsible for:

- developing RWRRIPs for inclusion in the SWRRIP

- facilitating the procurement of waste services on behalf of member councils

- providing waste education, under SV's coordination and oversight

- delivering specific projects as funded by SV or other organisations.

Councils

Councils provide a range of waste disposal and recycling services for their communities including:

- kerbside collection and disposal of general household garbage, hard rubbish, recyclables, and FOGO

- drop off for disposal and/or recycling of other specific types of items including metals, chemicals, oil, e-waste, paper, cardboard, garden organics and used printer cartridges

- operation of landfills for the disposal of waste

- commercial waste removal services in specific circumstances

- community education services about waste, resource recovery and litter.

Other roles and responsibilities

Government waste and resource recovery instruments—including the VORRS and MDS—also allocate roles and responsibilities to relevant agencies and councils.

For example, the RISP identifies the lead agencies for specific responsibilities. Some of these are shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Roles and responsibilities according to the RISP

|

Responsibilities |

Lead agencies |

|---|---|

|

Support local government and industry to transition to new contract arrangements for recycling services |

DELWP, SV |

|

Improve contracting and procurement processes used by local government for recycling services |

DELWP, MWRRG |

|

Improve the collection of recycled materials |

DELWP, SV |

|

Drive demand for products containing recycled materials through government procurement |

SV, Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) |

Source: VAGO, from the RISP.

1.5 Impact of the foreign export market

Chinese Sword Policy

According to SV data, in 2016–17 Victoria exported three-quarters of recovered plastic and nearly half of recovered paper and cardboard for offshore reprocessing. A significant amount of Victoria's waste export—nearly all plastic exports and 75 per cent of paper exports—went to China.

China formally announced that it was restricting its waste imports in a notice to the World Trade Organization in July 2017, and the restrictions went into force at the start of 2018.

However, in 2013 China had already been working to block imports of low‑quality recyclables under a crackdown referred to as the Operation Green Fence Policy. Customs officials increased their inspection of scrap plastic, paper, and metals to reject contaminated imports. Figure 1E shows that China's import of waste started decreasing in line with the implementation of the Operation Green Fence Policy.

Figure 1E

China's waste imports

Source: 'China tries to keep foreign rubbish out', The Economist, 3 August 2017, https://www.economist.com/china/2017/08/03/china-tries-to-keep-foreign-rubbish-out. Last accessed 23 March 2019.

Figure 1F shows that Australian exports to China started decreasing in 2013.

Figure 1F

Exports of waste materials for recycling by type from Australia to China, 2006–07 to 2017–18

Source: National Waste Report 2018.

The Chinese Government's decision to stop importing low-quality or unsorted plastic and paper recyclables led to the significant decline of Australian waste exports to China across the second half of 2017 and into the first half of 2018. According to SV-commissioned research in 2018, Australian export of paper, cardboard and plastic to China fell from 71 per cent (98 300 tonnes of the 139 400 tonnes total Australian export) in January 2017 to 24 per cent (25 300 tonnes of the 107 100 tonnes total Australian export) by February 2018. SV had not yet released data on 2017–18 Victorian waste during the audit.

The same SV-commissioned research noted that international commodity prices for these materials declined significantly from:

- $124 per tonne to $0 per tonne for paper and cardboard

- $325 per tonne to $55 per tonne for plastic.

Figure 1G illustrates the time line of the Chinese Sword Policy.

Figure 1G

Time line of Chinese Sword Policy

Source: VAGO.

Prior to the Chinese Sword Policy, many resource recovery facilities paid Victorian councils around $60 per tonne of recyclables, which offset the cost of providing the service to ratepayers. Resource recovery facilities then sold these materials to China.

When China started significantly restricting its importation of scrap paper, plastics and metal, these private resource recovery facilities notified Victorian councils that instead of being paid for these materials, councils would need to start paying $70 per tonne to have them collected.

Councils had little choice but to agree as the alternative would be to stop kerbside recycling services to Victorian households. The full impact of this contract revision varied from council to council but DELWP estimates it at about $120 to $150 per tonne on average.

1.6 Why this audit is important

The Victorian waste sector is currently facing many challenges, in particular the closure of export markets for recyclables. Illegal dumping, large-scale stockpiling of recovered resources, and illicit storage of hazardous chemicals are increasingly exposing the Victorian community to health and environmental risks.

Our 2011 Municipal Solid Waste Management performance audit report found that contrary to the objectives of the then Victorian waste policy Towards Zero Waste (TZW), waste generation in Victoria continued to rise. The audit found that a lack of effective planning, leadership, coordination, and oversight from responsible agencies hindered the effective implementation of TZW. The audit's three recommendations were all accepted.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

This audit examined whether responsible agencies are maximising the recovery and reprocessing of resources from Victoria's waste streams.

The audit reviewed the activities of DELWP, SV, EPA, MWRRG, and two metropolitan councils—Banyule Council and Monash Council.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $540 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2—Leadership for waste management

- Part 3—Understanding Victoria's waste data

- Part 4—Identifying and managing risks

- Part 5—Changing community behaviour.

2 Leadership for waste management

As Victoria's population grows, so too does the volume of materials we discard. In 2016–17 available data suggests that Victoria generated 12.9 million tonnes of waste. SV predicts that by 2046 this will reach 20 million tonnes—an increase of 55 per cent.

An effective waste and resource recovery system is essential to manage Victoria's waste to minimise the impact on the environment. Achieving this requires leadership and clear policy direction to drive coordinated effort across both state and local governments and the engagement and cooperation of businesses, communities and individuals.

2.1 Conclusion

DELWP's failure to fulfil its leadership role to ensure that the state operates under an overarching waste policy is depriving responsible government agencies and their stakeholders of a clear and definitive direction for waste management. This means that government responses to waste issues have been ad hoc and reactive.

In the absence of a statewide policy, agencies involved in waste management lack clear signals about what their priorities should be and how best to use their limited resources. DELWP's, SV's and MWRRG's six waste and resource recovery strategies and plans have myriad objectives and actions, which do not provide clear and coherent guidance in place of a statewide policy. Stakeholders, particularly some councils and waste operators, are confused about the roles and responsibilities of state-level agencies. Significant gaps in the waste instruments available lead to missed opportunities to improve waste management.

Further, DELWP, SV and MWRRG are not clearly and publicly reporting on the progress of the individual actions, overall objectives and outcomes of their strategies in a way that enables industry and the community to track their progress.

2.2 No statewide waste policy

Without a statewide waste policy, responsible agencies are operating in an uncertain environment and cannot effectively prioritise their limited time and resources.

GFV, which was published by the previous government in 2013, was the last statewide waste policy. DELWP advised us that after the 2014 election and change of government, GFV stopped being referred to as the state's waste policy. Some stakeholders and other relevant agencies we spoke to were not aware that, since 2014, GFV was no longer state policy.

The lack of a statewide policy since then has:

- caused frustration among relevant state agencies and local governments, making it more challenging to make decisions on which interventions to prioritise

- added to the confusion among councils and industry about the roles and responsibilities of SV and DELWP

- limited agency action in areas such as WtE—a clear policy would provide greater clarity and direction for EPA, MWRRG, councils, and industry in planning for WtE facilities.

DELWP advised that the 2017–18 Budget was the first opportunity it had to seek resourcing to address the policy gap. Although unsuccessful, a bid put forward for the 2017–18 Budget identified stakeholder concerns about the lack of a coherent overarching policy increasing business uncertainty.

State government policy is a critical tool that drives both public and private investment priorities. EPA and MWRRG informed us that economies of scale and the ability to sustain reliable markets for recovered waste materials requires predictable policy settings and investment certainty.

The 2018–19 Budget allocated $9.02 million for DELWP to create an evidence-based, whole-of-government waste policy and action plan to 2030 that incorporates circular economy principles and includes the government's position on WtE. DELWP advised us that it is working to finalise the policy by 2020. DELWP has developed a draft issues paper that it expects to release to the public as the first part of the policy's development.

Unclear roles and responsibilities

|

The WRR PCB oversees the development and delivery of policy, programs and projects in waste and resource recovery. It is made up of DELWP, SV, EPA and WRRGs. |

Despite changes arising from the recommendations of our 2011 report, Municipal Solid Waste Management, and the MAC Review, roles and responsibilities in the waste and resource recovery sector remain unclear.

DELWP has worked to improve the understanding of state agency roles and responsibilities through the establishment of the Waste and Resource Recovery Project Control Board (WRR PCB).

In 2015, through this forum, state agencies agreed on and documented their roles and responsibilities. However, in mid-2018 DELWP surveyed portfolio members to understand constituents' thoughts on the clarity of roles and responsibilities. The survey identified that there was residual ambiguity and a need for further clarity around the roles and responsibilities of each organisation. DELWP addressed these areas of ambiguity in its 2019 Waste and Resource Recovery Portfolio Collaboration Framework.

However, external stakeholders we spoke to through our audit consultation continue to find roles and responsibilities of key agencies confusing. This indicates that efforts to provide a greater understanding of the roles and responsibilities at a state agency level have failed to filter down to councils and industry.

The considerable number of disparate waste instruments that provide for agency tasks and functions adds to the confusion. For example, the RISP tasks SV and DELWP to assess different options to improve the collection of recycled materials. This is a specific function that has not been previously spelled out either in legislation or other waste instruments.

DELWP needs to clarify and set out in one document the roles and responsibilities of each agency responsible for waste management. In doing this, DELWP also needs to determine whether SV, MWRRG, EPA, and itself, have sufficient resources to undertake all the designated roles and responsibilities.

2.3 Unclear statewide guidance

SV developed the SWRRIP and MWRRG developed the MWRRIP in line with legislative requirements. Collectively, however, the six strategies and plans do not provide clear and coherent guidance on required or priority activities.

Figure 2A lists the six statewide waste strategies guiding the waste and resource recovery sector in metropolitan Melbourne. These identify 23 goals or objectives, 23 strategic directions and 103 actions.

Figure 2A

Content of waste and resource recovery strategies

|

Instruments |

Responsible agency |

Number of goals/ objectives |

Number of strategic directions |

Number of actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SWRRIP |

SV |

4 |

6 |

20 |

|

MWRRIP |

MWRRG |

4 |

N/A |

13 |

|

VORRS |

SV |

4 |

4 |

14 |

|

MDS |

SV |

7 |

7 |

N/A (in business plan) |

|

WES |

SV |

N/A |

6 |

45 |

|

RISP |

DELWP |

4 |

N/A |

11 |

|

Total |

23 |

23 |

103 |

Source: VAGO, from SV for the SWRRIP, MWRRIP, VORRS, MDS and WES and DELWP for the RISP.

There are also key gaps in these strategies and plans, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Waste and resource recovery strategies

|

Strategies and plans |

Responsible agency |

Implementation plan |

Lead agency identified for each action |

Time lines |

KPIs |

Public reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SWRRIP |

SV |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

MWRRIP |

MWRRG |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

VORRS |

SV |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

MDS |

SV |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

WES |

SV |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

RISP |

DELWP |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Total (✔/✘) |

2/6 |

3/6 |

3/6 |

3/6 |

1/6 |

Source: VAGO, from SV for the SWRRIP, MWRRIP, VORRS, MDS and WES and DELWP for the RISP.

Statewide Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Plan—quasi‑statewide policy

In the absence of a statewide waste policy, some councils and stakeholders have incorrectly considered the SWRRIP as Victoria's waste policy. This confuses the purpose of the SWRRIP, which is to provide a 30-year plan for the state's recovery, reprocessing and landfill infrastructure. The previous government designed the SWRRIP to be one of four key strategies and plans—including the MDS, VORRS and WES—to underpin the implementation of its overarching statewide waste policy, GFV.

This confusion has led Monash Council and some other stakeholders consulted during the audit to believe that SV and not DELWP is responsible for developing the statewide policy.

2.4 Limited implementation of statewide strategies

SV is not effectively implementing its four strategies guiding the waste and resource recovery sector in Victoria to ensure waste to landfill is minimised. The SWRRIP is a 30-year strategy, the MDS and WES have a 10‑year outlook, and the VORRS is a five-year action plan. Despite this, three years since their publication, SV does not have a clear plan to implement them. In particular, SV's limited and ineffective implementation of the VORRS is a missed opportunity to improve the recovery rate of organic material by 2020.

No implementation plans

SV's SWRRIP, VORRS, WES and MDS include some vague actions and do not provide specific guidance on how to achieve identified objectives. Actions indicated often have multiple projects sitting underneath them, but no implementation plan. This makes it difficult to determine the activities required to achieve identified objectives.

In contrast, each action included in the RISP is accompanied by a more detailed implementation description that identifies the expected outcome or target, time lines and lead agency.

SV developed the 2015–16 Delivery Plan for the SWRRIP, which includes a three‑year activities table that SV updates annually. 'Activities' are defined in the delivery plan as projects, programs and initiatives that are being undertaken by portfolio partners to deliver SWRRIP actions. For example, MWRRG is providing workshops, training and guidance to councils to improve their waste and resource recovery strategies. However, the activities table does not provide a detailed enough description of what needs to occur for responsible agencies to implement each action and for SV to implement the overall strategy.

No targets or performance measures

The SWRRIP is a 30-year strategy but does not identify any targets or immediate, intermediate or end measures for outputs or outcomes. This makes it difficult to understand how SV will determine and report on its progress. The VORRS, WES and MDS do not have targets, performance measures or specific requirements for the frequency of reporting.

Limited monitoring and reporting

Transparent public reporting on government performance is an important way to build and maintain public trust. This is particularly relevant given the importance of community involvement in minimising and recycling waste.

DELWP, SV and MWRRG publicly report on the completion of individual projects and programs within their strategies and plans in their annual reports. However, they are not clearly, transparently and publicly reporting on the progress of the actions, overall objectives and outcomes of their strategies in a way that enables industry and the community to track their progress or understand their impact.

SWRRIP reporting

SV monitors progress of the SWRRIP actions through its Evaluation Report and reports this to the WRR PCB annually. It raises project or activity status, risks and issues on an as needs basis through the WRR PCB.

SV does not have similar reporting for the VORRS, WES or MDS but rates their overall progress in the SWRRIP Evaluation Report. The assessments are imprecise, and the evidence base of the ratings is not clear given the lack of regular monitoring and reporting on actions in these strategies. SV only provides this full evaluation report to portfolio members, it does not report it publicly.

SV has released a progress report on the SWRRIP for 2015–17 and 2016–18, but these do not include an assessment of whether identified objectives are being achieved. These progress reports do not communicate clear outcomes to the Victorian community. Instead, they summarise key outputs and monitor performance indicators using self-reported surveys. SV does not clearly link activity reporting and performance measures with SWRRIP goals or collect primary data against the indicators.

Limited and delayed funding

EPA is responsible for collecting the Municipal and Industrial Landfill Levy (MILL) under the Act. EPA collects the MILL from licensed landfill operators, councils or commercial operators, and transfers it to the MILL Trust Account, managed by DELWP.