Safety and Cost Effectiveness of Private Prisons

Overview

Private prisons accommodate around one third of the state’s male prison population. The safe, secure and cost effective operation of these prisons is essential for the effective functioning of Victoria’s corrections system and for community safety. Like the broader prison system, private prisons face significant challenges. The male prison population has increased by approximately 50 per cent over the last seven years, primarily driven by an increase in remand prisoners.

This audit examines whether two of Victoria’s private prisons—Port Phillip Prison and Fulham Correctional Centre—are safe and cost effective. We looked at:

- private prisons’ management of critical safety and security risks

- private prisons’ performance against key service delivery measures, costs and risk transfer expectations under the original contracts

- the process for the recent contract extensions and whether they delivered value for money.

This is the first audit in which we used our ‘follow-the-dollar’ powers, directly engaging the private prison operators and requesting information from them.

We made six recommendations for DJR, and two for the Department of Treasury and Finance related to its role in the private prison contract extension process.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2018

PP No 384, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Safety and Cost Effectiveness of Private Prisons.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

29 March 2018

Acronyms and abbreviations

| ACI | Australasian Correctional Investment Ltd |

| CMB | Contract management branch |

| CCTV | Closed‑circuit television |

| CV | Corrections Victoria |

| CVIU | Corrections Victoria Intelligence Unit |

| DJR | Department of Justice and Regulation (and its predecessor, Department of Justice) |

| DPC | Department of Premier and Cabinet |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| GEO | The GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd |

| G4S | G4S Custodial Services Pty Ltd |

| IMR | Internal management review |

| JARO | Justice Assurance Review Office (formerly the Office of Correctional Services Review) |

| KPI | Key performance indicators |

| MAP | Melbourne Assessment Prison |

| MRC | Metropolitan Remand Centre |

| OHS | Occupational health and safety |

| OCSR | Office of Correctional Services Review |

| OPCAT | Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment |

| OV | Occupational violence |

| PIMS | Prisoner Information Management System |

| PIU | Prison intelligence unit |

| PPP | Public–private partnership |

| PSC | Public Sector Comparator |

| PPRF | Private Prison Reporting Framework |

| SDO | Service delivery outcome |

| SSU | Security Standards Unit |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

Audit overview

Victoria's prison system faces significant challenges and risks:

- Male prisoner numbers increased by approximately 50 per cent over the last seven years, including significant growth in remand (unsentenced) prisoners.

- The prisoner population is increasingly complex, with mental health conditions, drug and alcohol issues, and chronic illnesses.

- Across the system, 43.6 per cent of prisoners returned to prison within two years in 2016–17.

- Young prisoners, prisoners with disabilities and prisoners of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background are over‑represented.

Private prisons are part of the broader prison system in Victoria and, as such, are not immune to the challenges posed by a growing and increasingly complex prisoner population.

Victoria's privately operated prisons accommodated around one third of the state's male prisoners in December 2017. The safe, secure and cost-efficient operation of these private prisons is essential, both for the effective functioning of Victoria's corrections system and for community safety.

Corrections Victoria (CV), a division of the Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR), is responsible for managing the contracts with the private prison operators to ensure the safe custody and welfare of prisoners.

In this audit, we examined two of the three privately operated prisons in Victoria:

- Port Phillip Prison (Port Phillip) is a maximum-security men's prison in Melbourne's west. G4S Correctional Services (Australia) Pty Ltd, and its successor G4S Custodial Services Pty Ltd (G4S), has operated Port Phillip since 1997. G4S recently commenced a new contract term of up to 20 years. Port Phillip has more prisoners than any other prison in Victoria and, at December 2017, nearly half of these were remand prisoners. Port Phillip is also unique in that it provides statewide prison medical services and specialist services for intellectually disabled prisoners. It has more prisoner movements, in and out, than any other prison in the corrections system.

- Fulham Correctional Centre (Fulham) is a medium-security men's prison near Sale. The state has contracted Australasian Correctional Investment Ltd (ACI) to operate this prison since 1995. ACI is a special-purpose company established by The GEO Group, with The GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd (GEO) subcontracted as the prison operator. GEO commenced a new contract term of up to 19.25 years in July 2016. Fulham first accepted remand prisoners in September 2015. In December 2017, remand prisoners accounted for around 25 per cent of Fulham's population.

In this audit, we focused on whether these private prisons are safe and cost effective. In particular, we examined how well the private prisons are managing safety and security risks and whether they met the state's expectations for service delivery, cost and risk transfer during the original contract terms. We also assessed how well DJR and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) managed negotiations for the new contracts and whether they achieved value for money.

We did not examine Victoria's third private prison, Ravenhall Correctional Centre (Ravenhall), as it commenced operation in November 2017, after this audit began.

Conclusion

G4S and GEO deliver cost-efficient services for the state that have largely met the contracts' service and performance requirements. Port Phillip and Fulham cost up to 20 per cent less to run than the average for publicly operated prisons of the same security rating.

CV demonstrates sound contract management and genuine engagement with the private operators of Port Phillip and Fulham. DJR successfully negotiated new contracts for the operation of these prisons that address key weaknesses in the initial contractual arrangements, at a cost consistent with government expectations.

However, the prison operators are not always meeting the state's service and performance requirements to run safe and secure prisons, particularly in relation to assaults at both prisons and drug use at Port Phillip. This is consistent with system-wide performance.

Serious incidents at both Port Phillip and Fulham have, in some instances, exposed weaknesses in how G4S and GEO manage safety and security risks, and neither operator is investigating serious incidents using methods that effectively identify root causes. The operators and CV need to improve how they address the risks inherent in the prison environment to better discharge their shared duty of care to prisoners, prison staff and the community.

Prisoner-on-prisoner assaults is increasing across the prison system, as prisoner numbers and complexity increases. Private operators and CV have violence‑reduction strategies in place, but there is a need to better evaluate these and share the lessons learnt.

Findings

Private prison performance

Performance results

CV measures prison performance against service delivery outcomes (SDO), which cover prisoner safety, security, health, welfare, activities and programs. Applicable SDOs and performance thresholds vary for each prison, depending on the prison's security level, prisoner profile and past performance. DJR's target is to meet 90 per cent of SDO thresholds.

Fulham's performance against its SDOs has been largely positive since 2010−11, apart from a decline in performance in 2012–13, partly related to a single incident involving several staff injuries.

Port Phillip has failed to meet a greater number of performance thresholds than Fulham relating to prisoner-on-prisoner assault, assaults against staff and positive random drug tests.

The new contracts include key performance indicators (KPI), with 18 that apply to Port Phillip and 16 to Fulham. These cover health services, facility and asset management, performance and incident reporting, prisoner reintegration and prisoner management. The KPIs significantly increase the requirements for the private operators to maintain their facilities and, importantly, require private prisons to turn around poor performance quickly and provide accurate performance data. These KPIs do not apply to public prisons. Under the new contracts, CV continues to measure the performance of private prisons monthly, and calculates performance-linked payments quarterly rather than annually. This increases pressure on private prisons to consistently meet performance requirements.

Monitoring private prisons

CV scrutinises private prison performance more than public prisons, including validating the operators' self-reported performance data.

This is important, as achieving an appropriate transfer of risk to the private operators was a key objective of the initial contracts. Those contracts allocated the financing risks for construction of the new prison facilities to the private operators. The operators also took on the operational risks associated with accommodating prisoners and delivering correctional services to agreed service standards.

DJR's management of the private prison contracts has significantly improved since our 2010 audit Management of Prison Accommodation Using Public Private Partnerships. CV has an almost constant presence at both prisons and routinely checks contractual compliance to support performance and maintain the allocation of risks agreed in the initial contracts.

CV has responded appropriately to poor performance including significant safety and security breakdowns, requiring the operators to develop and implement plans to address the underlying issues and causes.

CV uses a variety of graduated responses to address operators' underperformance, and engages and supports the operators to manage risks. This reflects the mature contractual relationship developed between the parties. Since 2012, CV has appropriately issued five contract default notices in response to serious performance concerns. To date, the operators have complied with the requirements of the default notices to implement corrective action plans, known as 'cure' plans.

CV's increased oversight and scrutiny of private prisons is positive, however, it is not possible to determine whether it has resulted in improved performance. CV and the prison operators monitor and regularly discuss these corrective action plans, but they do not routinely evaluate the impact of their improvement activities.

CV collects a significant amount of data from all prisons, but its legacy IT systems are not integrated and this hinders its ability to analyse data effectively. CV cannot use this data to fully understand the trends and issues that may affect prisons' performance, safety, security and costs across the corrections system.

Despite the large amount of information CV holds on prison performance, little data on whether Victoria's prisons are safe, secure and meeting performance requirements is publicly available. CV currently publishes information about drug testing and contraband seizures in prisons, but does not publish prison‑specific performance results relating to other safety and security matters such as assaults, deaths and escapes. This reduces the transparency of the Victorian corrections system.

Costs

The privately operated prisons cost the state up to 20 per cent less to run than the average for publicly operated prisons of the same security rating. This is consistent with DJR's advice to government in recent years that the two privately operated prisons are cheaper to run than public prisons, largely due to more efficient staff shift patterns.

Safety and security of private prisons

Prisoner-on-prisoner assaults are increasing at Port Phillip and Fulham, particularly Level 1 assaults, which involve an injury that does not require admission to hospital. This is consistent with the broader prison system as it deals with capacity pressures, increasing remand population, increased prisoner movement through the system and an increasingly complex prisoner profile. Assaults on staff also increased in 2015–16 and then again in the first half of 2016–17 across the corrections system, and are more common at maximum‑security prisons including Port Phillip.

Fulham and Port Phillip have both developed violence-reduction strategies to address this risk. Port Phillip's strategy is comprehensive and involves a broad range of activities targeting violence, which reflects the higher risks at that prison. It involves dedicated resources and has recently broadened to include a specific focus on occupational violence (OV). Fulham's strategy also includes a range of activities to minimise the risk of assault on prisoners and staff, such as staff communication and training, prisoner employment and programs. Both prisons have a strong focus on reducing violence and improving performance in this area. They closely monitor incidents of violence and SDO performance, however, neither prison periodically evaluates its strategies to ensure they are working and based on current evidence.

CV has a system-wide OV strategy, but this does not specifically address prisoner-on-prisoner assaults. There is no planned evaluation of the strategy and no coordinated process for capturing and sharing the lessons of the various prison strategies.

Serious safety and security incidents have occurred at both private prisons since 2010–11, including escapes, a riot, unnatural deaths and serious assaults. CV and the private operators have worked well together to respond to these incidents, but the investigation process lacks a contemporary methodology to analyse the root cause. This creates the risk that corrective actions will not successfully prevent further incidents.

Negotiating new private prison contracts

While negotiating new contracts, DJR successfully navigated significant challenges to ensure service continuity at Fulham and Port Phillip. The new contracts addressed key weaknesses in the initial contractual arrangements and broadly met the cost limits approved by government. Advice to government throughout the process was sound, with some minor exceptions that did not invalidate the outcomes achieved.

These transactions were unique given the context within which they occurred. The processes used by DJR did not fully align with DTF's Partnerships Victoria requirements for public–private partnership (PPP) projects. However, DTF accepted these departures from the usual requirements, and the close involvement from senior DJR officers, DTF and the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) meant there was adequate oversight and review of the options analysis and negotiation process.

DJR analysed the most viable procurement options early enough to protect the state's negotiating position. This analysis found that the state was likely to incur significant additional costs if it competitively tendered the operation of the prisons or decided to operate them itself.

The expected additional costs related largely to the need to buy out leases held by GEO and G4S over the prison sites, which extended well beyond the 2017 expiration dates of their contracts. These long‑term land leases were part of the initial contract arrangements entered into in the 1990s.

The original Crown leases were to expire in 2035 for Fulham and 2046 for Port Phillip. This misalignment of the lease terms with the service contract terms was a key reason for the state negotiating extended contracts with the incumbent operators, and ultimately served to reduce competitive tension. The revised lease terms now align with the new service contract terms of up to 20 years.

DJR developed and implemented a robust strategy to negotiate the new contracts with the operators. Cost was the main criteria assessed and highlighted in advice to government on whether to enter into new contracts. DJR took reasonable steps to gain assurance about the value for money of the proposals put forward by the operators, including targeted examination of the operators' actual operating costs.

DJR only examined service performance at a cursory level, and we saw no detailed assessment of whether the incumbent operators were capable and high-performing providers. DJR's concerns about G4S's performance during 2014 received little coverage in advice to government on whether to negotiate with the incumbent operator.

A commercial adviser working for DJR and one of the operators during the negotiations for the new contract did not adequately disclose conflicts of interest and these were not adequately assessed, or acknowledged in advice to government.

The new contracts negotiated with the operators addressed substantial weaknesses in the previous contracts. They will place the state in a much stronger position at the end of the new service terms to consider and pursue all available options, including competitively tendering the contracts, unencumbered by substantial legacy issues or costs.

DJR needs to manage these contracts effectively to achieve value for money in both performance and cost in the future. This is a significant challenge, but DJR has established robust contract administration guidance and processes to support this task.

Recommendations

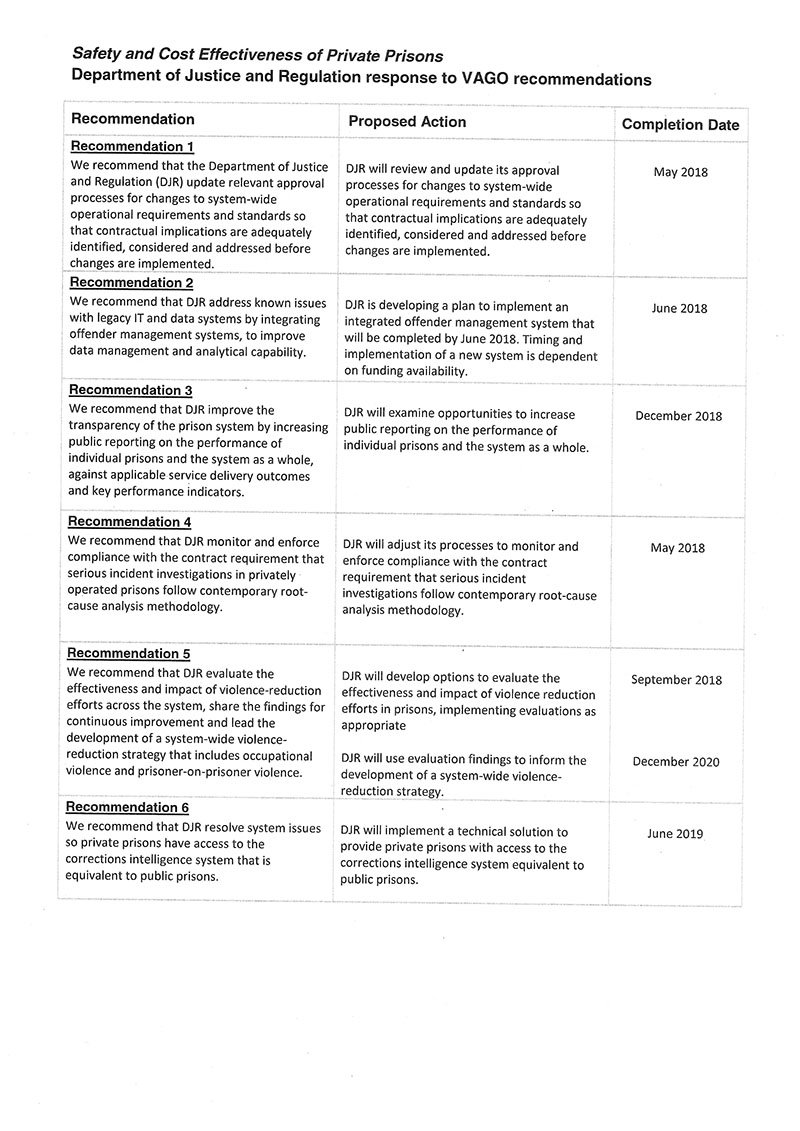

We recommend that the Department of Justice and Regulation:

1. update relevant approval processes for changes to system-wide operational requirements and standards so that contractual implications are adequately identified, considered and addressed before changes are implemented (see Section 2.2)

2. address known issues with legacy IT and data systems by integrating offender management systems, to improve data management and analytical capability (see Section 2.3)

3. improve the transparency of the prison system by increasing public reporting on the performance of individual prisons and the system as a whole, against applicable service delivery outcomes and key performance indicators (see Section 2.4)

4. monitor and enforce compliance with the contract requirement that serious incident investigations in privately operated prisons follow contemporary root-cause analysis methodology (see Section 3.2)

5. evaluate the effectiveness and impact of violence-reduction efforts across the system, share the findings for continuous improvement and lead the development of a system-wide violence-reduction strategy that includes occupational violence and prisoner-on-prisoner violence (see Section 3.5)

6. resolve system issues so private prisons have access to the corrections intelligence system that is equivalent to public prisons' access (see Section 3.6).

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance:

7. ensure that its advice to government, and associated public information on Partnerships Victoria and other major projects, should wherever practicable present costs and benefits in nominal and present value terms, with the discount rate (nominal and/or real rate) and other key assumptions explicitly stated and justified (see Sections 5.2 and 5.3)

8. update relevant guidance to require probity reports and sign-off letters for major procurement transactions to disclose any material probity issues that arose during the relevant project, even where the issues were managed to the satisfaction of the probity practitioner and project governance group (see Section 5.3).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DJR, DTF, G4S and GEO, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to DPC.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses from each agency are included in Appendix A.

DJR acknowledged the insights the audit has provided and accepted all of the recommendations. DTF also accepted the recommendations, and both agencies have provided an action plan detailing how they will address the recommendations.

While the recommendations were not directed to GEO or G4S, both private prison operators supported the audit findings and the recommendations made.

1 Audit context

The Victorian adult corrections system includes more than 50 community correctional facilities, 14 prisons and a transition centre. Figure 1A shows the prisons and transition centre, along with their operational capacity, at December 2017.

Figure 1A

Victoria's prison system

(a) Ravenhall was partially operational as at December 2017. Its full operational capacity is 1 000.

Source: VAGO based on operational capacity data provided by CV.

Each prison has unique characteristics and its own complexities and challenges, including:

- prisoner profile—sentenced or remand prisoners, sex offenders, young adult offenders, prisoners with intellectually disabilities and those requiring protection or separation due to particular risks or vulnerabilities

- the type of service provided—reception prison, preparation for release, hospital services.

Victoria's privately operated prisons

| The initial contracts required accommodation services for around 600 prisoners in fit-for-purpose buildings and facilities, with the majority of prisoners in single cells, and a safe and secure environment, including a secure physical prison perimeter. |

Since 1997, Victoria has contracted three privately operated 'full-service' men's prisons under PPP arrangements—Fulham, Port Phillip and Ravenhall. We did not examine Ravenhall in this audit as it only commenced operations in November 2017. The Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, previously the Metropolitan Women's Correctional Centre is a maximum‑security women's prison, which was contracted to a private operator in 1996, but returned to state control in 2000 due to concerns with the management of the prison.

Under their contracts, the operators of Fulham and Port Phillip provide accommodation services (suitable facilities for prisoner containment) and correctional services (safe custody and welfare of prisoners in their care). Correctional and accommodation services are required to comply with relevant legislation and state policies, as well as contractual obligations.

|

Contracted correctional services included:

|

The private operators, sub‑contractors or CV also provide prisoner education and employment programs and health services.

The initial private prison contracts specified SDOs and performance thresholds, and enabled performance-based payments to the operators. The contracts addressed the state's access rights, insurance requirements and required facility maintenance.

GEO operates Fulham, a medium-security men's prison located near Sale, in eastern Victoria. Fulham accommodates medium-security mainstream and protection prisoners in cellblocks and cottages, as well as minimum-security prisoners in units. Fulham also has a minimum-security annexe, Nalu, a unit initially intended for young offenders aged 18–25 that now houses all age groups.

G4S operates Port Phillip, a maximum-security men's prison located in Truganina, to the west of Melbourne. Port Phillip accommodates prisoners with diverse needs, including mainstream prisoners and those requiring protection or separation in high-security units. It has a psychosocial unit, a youth unit for young adult offenders, and a special care unit for vulnerable and intellectually disabled prisoners. Port Phillip has a 20-bed in-patient facility within its walls, providing primary and secondary health care to prisoners from across the corrections system. Port Phillip is also responsible for managing the security of all prisoners in the secure or non-secure wards at St Vincent's Hospital.

In comparison to other Australian states, Victoria has the largest percentage of its total number of male prisoners in private prisons. With Ravenhall now in operation, Victoria has more privately operated prisons than any other state in Australia. Figure 1B shows key metrics for Fulham, Port Phillip and Ravenhall.

Figure 1B

Key metrics for Victoria's full-service private prisons at December 2017

|

Metric |

Private prison |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fulham |

Port Phillip |

Ravenhall |

|

|

Operational capacity |

893 |

1 087 |

700(a) |

|

Percentage of state bed capacity in men's prisons |

12% |

14% |

9% |

|

New contract commencement |

1 July 2016(b) |

10 September 2017 |

Build phase—15 September 2014 |

|

Contract term |

11 plus 8.25 years |

10 plus 10 years |

25 years (operational phase) |

|

Contract expiry |

October 2035 |

September 2037 |

October 2042 |

Note: Operational capacity percentages are rounded figures.

(a) Ravenhall has not reached its full operational capacity of 1 000. Ravenhall also includes an option to increase capacity to 1 300.

(b) The initial Fulham contract was due to expire in April 2017. The state and GEO signed the new contract in April 2015 and agreed that it would commence in July 2016.

Source: CV.

Terms of the Fulham and Port Phillip contracts

The initial contracts for Fulham and Port Phillip required the design, finance, construction, operation and maintenance of the prisons for up to 20 years. The contracts included an option to negotiate an extension. The initial contracts were due to expire in 2017.

Significantly, the initial arrangements also provided the operators with long‑term leases over the land on which the prisons were constructed. These Crown leases were to expire in 2035 for Fulham and 2046 for Port Phillip. The misalignment of the lease terms with the service contract term was one of the reasons for the state negotiating extended contracts with the incumbent operators.

DJR finalised negotiations during 2015 for new contracts with both operators. The new contracts have maximum terms of up to 20 years, subject to the operators meeting performance requirements, and are forecast to cost the state approximately $4.5 billion in nominal terms if they run their full term. The revised lease terms now align with the 20-year service contract terms.

Systemic issues and challenges

Prison performance is influenced by many factors, and the Victorian system faces ongoing challenges due to a growing and increasingly complex prisoner population.

Increase in prisoner numbers

In December 2017, Victoria had 7 131 prisoners, 93 per cent of whom were male. As shown in Figure 1C, prisoner numbers have fluctuated but overall increased from an annual average of 4 272 in 2010–11 to 6 383 in 2016–17. During this period, Port Phillip's prisoner numbers increased by an average of 5 per cent annually and Fulham's numbers fluctuated but on average increased by 2 per cent annually.

Figure 1C

Annual average number of male prisoners, 2010–11 to 2016–17

Source: VAGO based on the daily and monthly averages for each prison provided by CV.

Prison utilisation rates

The operational capacity of a prison is the total number of beds available for prisoners. In December 2017, the men's prison system had an average daily operating capacity of 7 694 places for 6 638 prisoners. Operational capacity includes any additional beds in cells over and above their design capacity—for example, single cells that now accommodate bunk beds. Excluded from operational capacity are cells dedicated to short-term management of prisoners (often after an incident), some specialist beds such as hospital beds and observation cells, and cells closed for an extended period of maintenance.

CV regularly monitors each prison's utilisation rate based on its operational capacity. DJR's output performance measures published in the 2016–17 State Budget included a utilisation target of 90 to 95 per cent and it achieved an outcome of 94 per cent in 2016–17. CV advised that this target reflects the need to have sufficient flexibility in the system to deal with maintenance, prisoner movement and placement needs, and to respond to incidents.

Figure 1D and Figure 1E show that utilisation rates have fluctuated in all men's prisons since 2011–12. Port Phillip has consistently higher utilisation rates than the average of the other maximum-security prisons and is consistently at or above the 95 per cent utilisation target except in quarter four 2014–15. CV advised that Port Phillip's utilisation rate can reach above 100 per cent due to the use of special-category prison beds, such as hospital beds, that are not counted in operational capacity.

Fulham's utilisation has fluctuated, and between 2014–15 and 2015–16 dropped below the average of other medium-security prisons. CV attributes this to the opening of the Middleton facility at Loddon prison and expansion at other prisons.

The riot at the Metropolitan Remand Centre (MRC) in June 2015 also resulted in an increase in utilisation rates at both Port Phillip and Fulham in 2015–16, after a period of lower utilisation in 2014–15.

Figure 1D

Daily average utilisation at Port Phillip compared to the average at other maximum-security prisons (excluding Port Phillip), 2011–12 to 2016–17

Note: Port Phillip's average daily utilisation reached above 100 per cent due to the use of special-category prison beds (such as hospital beds).

Source: VAGO based on data provided by CV.

Figure 1E

Daily average utilisation at Fulham compared to the average at other medium-security prisons (excluding Fulham), 2011–12 to 2016–17

Source: VAGO based on data provided by CV.

Increase in remand prisoners

|

A remand prisoner is a person against whom a charge has been laid but not proven in court. The prisoner has not been released on bail and is in prison awaiting trial. |

The profile of prisoners has changed over the last decade, with an increase in the remand population from 17 per cent of the total men's prison population in the first quarter of 2010–11 to 30 per cent at the end of 2017, as shown in Figure 1F. This increase in remand prisoners is linked to reforms of the parole and bail systems, as well as a greater number of police detecting more offences. The MRC riot in June 2015 also resulted in remandees being moved to other maximum- and medium-security prisons.

In December 2017, 45 per cent of Port Phillip's prisoners were remand prisoners, down from an annual average of 51 per cent in 2016–17. Fulham started to receive remand prisoners in 2015 and, in December 2017, remand prisoners accounted for 25 per cent of Fulham's population.

Figure 1F

Percentage of remand prisoners in all male prisons, July 2010 to December 2017

Source: VAGO based on data provided by CV.

A November 2016 report by DJR's Office of Correctional Services Review (OCSR)—now the Justice Assurance Review Office (JARO)—found that remand prisoners may face particular challenges. The report found that, for the period reviewed, male remand prisoners were potentially more vulnerable than sentenced prisoners due to the effects of drug and alcohol withdrawal, young age, potential of undiagnosed medical illness and the risk of being subject to standover behaviour from other prisoners.

In addition, remand prisoners have comparatively short and uncertain periods in custody and contribute to the increasing number of prisoner movements, as they have more court appearances than a sentenced prisoner. Based on the presumption of innocence, remand prisoners are entitled to less restrictive conditions and have different rights to sentenced prisoners. They are not mandated to participate in programs or work. While remand prisoners should have separate accommodation units to sentenced prisoners, this is not always achievable due to system-wide capacity issues.

Prisoner movement

There are many prisoner movements to, between and from Victoria's prisons, including:

- reception into prison

- discharge from prison

- progression or regression within a prisoner's sentence or classification

- court appearances

- medical needs and hospital treatment

- short prison sentences

- prison transfers for safety needs or to access particular leave permits.

|

Reception prisons are the first point of contact for prisoners entering the prison system. By their nature, reception prisons have a high volume of prisoner movements. In Victoria, men's reception prisons include MRC, Melbourne Assessment Prison (MAP) and, since November 2017, Ravenhall. Port Phillip can act as a reception prison, but the state has not used this capability frequently in recent years. |

The transient nature of prison populations results in a constantly changing prison culture and dynamic. This poses a risk for prison operators in ensuring the safety and security of prisoners and prison staff. The number of prisoner movements varies greatly between prisons depending on the particular services a prison provides. For example, Port Phillip is the largest male prison and is a central hub for the prison system—prisoners may transfer to Port Phillip from across the system to be near Melbourne's courts, to receive medical treatment and to prepare for discharge. Remand prisoners also experience more movements due to court appearances.

Port Phillip has the greatest number of prisoner movements of any Victorian prison, because of its large population and the services it provides. Figure 1G shows that the number of prisoner movements at Port Phillip is consistently higher than MRC and the average of other maximum-security prisons. Movements increased at Port Phillip and MRC in 2014–15, with court-related movements and prisoner discharges contributing the most to this increase. The difference between Port Phillip and MRC prisoner movements increased over the last two years, potentially due to the impact of the MRC riot and increased proportion of remand prisoners. In comparison, the average of all other maximum-security prisons is lower and this is primarily due to Barwon Prison having a low number of movements.

When movements are calculated as the number of movements per prisoner per year, Port Phillip and MRC are the same, with an annual average of 19 moves per prisoner between 2010–11 and 2016–17.

Figure 1G

Prisoner movements at Port Phillip and MRC compared to the average at maximum-security prisons (excluding Port Phillip), 2010–11 to 2016–17

Note: Movements include all transfers in and out of the prison, receptions and discharges. Court transfers and movements for leave permits (related to health, justice administration, community work, rehabilitation and transition and other approved reasons) are counted as movements.

Source: VAGO based on movement data provided by CV.

Figure 1H shows that Fulham has consistently more prisoner movements than Marngoneet Correctional Centre (Marngoneet), a comparable public medium‑security prison. This difference is partly due to higher prisoner numbers. When compared to the average of all other medium-security prisons, Fulham's average annual number of movements is around double the average for other medium-security prisons.

However, when we take into account the number of prisoners at a prison, Fulham's rate of movement per prisoner per year is similar to the average of other medium-security prisons. On average, Fulham's annual average rate of movements between 2010–11 and 2016–17 is 9.6 movements per prisoner and the average of other medium security prisons is 9.5 movements per prisoner.

Figure 1H

Prisoner movements at Fulham and Marngoneet compared to the average at medium-security prisons (excluding Fulham), 2010–11 to

2016–17

Source: VAGO based on movement data provided by CV.

Increase in assaults

Victoria's prison system is experiencing an increase in assaults. Figure 1I shows the rate of assaults against prisoners and staff in Victoria's prisons over the last four years in men's prisons. In July 2013, there were 63 assaults and 5 022 male prisoners, and in June 2017 there were 133 assaults and 6 622 male prisoners. While the rate of assaults per 100 prisoners fluctuates monthly, on average it increased by 2 per cent per month across all men's prisons in this period. Many prisons, public and private, are not meeting performance thresholds for prisoner‑on‑prisoner assaults.

CV and prison operators attribute the increase in assaults to rising prisoner numbers and movements, the increasing proportion of remand prisoners and a more complex prisoner profile including a higher rate of prisoners with mental illness or intellectual disabilities, or suffering drug withdrawal.

Figure 1I

Monthly rate of prisoner and staff assaults per 100 prisoners in men's prisons, 2013–14 to 2016–17

Source: VAGO based on data provided by CV.

1.1 Relevant legislation and regulation

Corrections Act 1986

The Corrections Act 1986 (the Act) and the Corrections Regulations 2009 (the Regulations) provide the legislative basis for adult correctional services in Victoria. Relevant parts of the Act:

- provide for the establishment, management and security of prisons and the welfare of prisoners

- allow the state to contract out the provision of correctional services

- assign clear responsibilities to the Secretary of DJR and, specifically, the Commissioner of CV (the Commissioner) to monitor the performance of all correctional services to achieve the safe custody and welfare of prisoners.

This means that, while the Act allows the state to contract out the operation of prisons and ancillary services, the state retains a duty of care to all prisoners and is accountable to the community for the operation and cost of all prisons.

Victorian Correctional Management Standards for Men's Prisons

The Victorian Correctional Management Standards for Men's Prisons (the Standards) reflect the requirements of the Act and the Regulations. The Standards focus on the desired outcomes and outputs for public and private prisons, and provide a basis for prison operating procedures. They also provide the framework against which CV monitors prison services.

The Standards cross-reference the national Standard Guidelines for Corrections in Australia, to which CV is a signatory. These guidelines act as outcomes or goals to be achieved by correctional services, rather than a set of absolute standards or laws to be enforced.

Commissioner's Requirements

The Commissioner issues Commissioner's Requirements to all prisons to promote consistency and continuity of operational practice across the whole prison system. CV consults with prison management to develop the Commissioner's Requirements.

There are 66 Commissioner's Requirements related to:

- security and control

- prisoner management

- programs and industry

- prisoner services

- prisoner health.

The private prisons are required to document their operating procedures in an operating manual, which must comply with the Commissioner's Requirements. The operating manual includes a range of operating instructions, which the Commissioner endorses.

1.2 Roles of agencies and associated entities

Corrections Victoria

CV, a division of DJR, is responsible for the establishment, management and security of all public and private prisons in line with the relevant legislative requirements. CV's key functions include:

- the statewide provision of correctional operations

- setting standards and monitoring performance

- developing and delivering correctional strategy, policy and programs.

These functions aim to achieve the safe custody and welfare of prisoners and community-based offenders.

Justice Assurance Review Office

JARO operates as an internal review and assurance function to advise the Secretary of DJR on the performance of Victoria's youth justice and corrections systems. JARO is separate from the department's Youth Justice Division and CV, and acts as an additional line of defence against emerging and enduring risk within both systems. JARO reviews all deaths in custody and some serious incidents, as well as conducting thematic reviews of systemic issues.

Private prison operators

GEO operates Fulham under a contract with ACI, which has the contract with the state. ACI is a special‑purpose company established by The GEO Group, which is an American multinational company providing corrective and detention services worldwide.

Port Phillip is operated by G4S—part of a large multinational company operating in over 100 countries.

Monitoring prisons

CV's various divisions support and monitor the private prison operators, as shown in Figure 1J.

Figure 1J

CV divisions and their roles in service delivery and overseeing private prisons

|

Business services |

|

|---|---|

|

Strategic policy and planning |

|

|

Operations |

|

|

Offender management |

|

|

Sentence management |

|

|

Security and intelligence |

|

Note: This list does not show all functions provided by CV divisions. It includes only the functions that relate to this audit.

Source: VAGO based on information from CV.

Performance framework

All prisons must report on their performance against specified SDOs, which cover prisoner safety, security, health, welfare, activities and programs. The performance thresholds for SDOs vary for each prison based on the security level of the prison, prisoner profile and past performance. CV monitors SDO performance and provides monthly and quarterly performance reports to the Commissioner.

The new contracts for Fulham and Port Phillip, signed in 2015, retained the existing SDOs and included 18 additional KPIs for Port Phillip and 16 for Fulham. The contracts also redesigned the performance framework to:

- focus more strongly on facility maintenance

- introduce a quarterly performance outcome, instead of annual

- restructure the thresholds and associated performance payments so they are scaled according to the prison's level of performance.

The new KPIs applied to Fulham for the 2016–17 year and Port Phillip from September 2017. They cover a range of performance areas including health care, facility maintenance, reintegration programs and recidivism, although not all the KPIs apply at both prisons. The KPIs do not apply at Victoria's public prisons, and CV has no plans to implement them due to the administrative burden this would place on the prisons.

The eight SDOs and two KPIs relating to prison safety and security are:

- SDO 1—escapes

- SDO 2—assaults on staff by prisoners

- SDO 3—out-of-cell hours

- SDO 4—number of unnatural deaths

- SDO 5—self harm

- SDO 6—assaults on prisoners by other prisoners

- SDO 7—assaults on prisoners by staff

- SDO 8—random general urinalysis

- KPI 6—releases on the correct date

- KPI 11—incident reporting.

The safety and security SDOs and KPIs in the new contracts use various measures:

- zero tolerance—requires 100 per cent compliance or nil incidents

- a percentage result—for example, positive drug tests

- number of incident points per quarter—adjusted to account for prisoner numbers.

Excluding the zero tolerance indicators, each of the SDOs and KPIs above has a threshold that the prisons are required to meet. See Appendix B for full details on SDOs and KPIs.

Unlike public prisons, private prisons have a performance regime with associated payments outlined in their contracts. In the private prisons, performance thresholds form part of the commercial negotiations between the state and the operator, and there are financial implications when private prisons do not meet the thresholds. In the public system, performance outcomes are not linked to financial penalties. CV considers that this provides it with more flexibility to alter the thresholds for public prisons and potentially implement stretch goals.

Our May 1999 audit Victoria's Prison System: Community protection and prisoner welfare found that the initial contracts with the operators of Fulham and Port Phillip did not encourage service excellence. The SDO thresholds in these contracts were not based on average performance but on the lowest standard achieved by comparable public prisons during the previous three-year period. The audit also found that DJR applied less scrutiny to public prison operations and performance than to private prisons.

The initial contracts allowed CV to amend SDO thresholds over time based on the state's requirements and commercial negotiations with the operators. These negotiations and updates to SDO thresholds occurred as part of the five-yearly service term renewal process under the contracts.

1.3 Previous audits

Our September 2010 report Management of Prison Accommodation Using Public Private Partnerships found that the former Department of Justice faced significant challenges and problems managing these long-term contracts. This was partially due to the contracts not adequately defining quality standards, but was also the result of ineffective administration of the contracts, lack of adequate performance monitoring, complex governance arrangements and inadequate risk management.

Our October 2013 report Prevention and Management of Drug Use in Prisons found that the processes for identifying prisoners who use drugs were generally effective. However, weaknesses in performance reporting and evaluation meant that the former Department of Justice could not determine whether initiatives to manage drug use in prisons were effective.

Other recent audits of prisons include Prison Capacity Planning (November 2012) and Prisoner Transportation (June 2014).

1.4 Why this audit is important

In recent years, there has been growing public concern about safety risks at Victoria's prisons, and their implications for prisoners, employees and the public. Recent incidents have contributed to the public's concerns—for example, prisoners escaping over the wall at Fulham (2016), a prisoner escaping from Port Phillip's custody at St Vincent's Hospital (2017), prisoners rioting at MRC (2015) and numerous other violent incidents at Victorian and interstate prisons and youth justice facilities.

The operation of Victoria's prisons is a considerable expense for the state. Understanding the cost of operating private prisons compared to public prisons is important for an accountable and transparent prison system. Equally important is the ability to evaluate whether the recent contract extensions for Port Phillip and Fulham provide value for money.

1.5 What this audit examined and how

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Victoria's private prisons are safe and cost effective.

We examined whether:

- private prisons are appropriately managing critical safety and security risks

- private prisons met the state's key service delivery, cost and risk transfer expectations under the old contracts

- the recent contract extensions achieved value for money.

We limited our comparison of the private prisons' performance and cost to other male prisons:

- We compared Port Phillip's performance outcomes to MRC, and we compared Fulham's to Marngoneet, to reflect similarities such as prison profile, size and volume of prisoner movements.

- We compared Port Phillip's financial performance to MRC and Barwon, and we compared Fulham's to Loddon and the average of other medium‑security prisons (which includes Loddon). These financial comparisons are consistent with the value-for-money comparisons the state undertook when negotiating the new contracts.

We excluded the two women's prisons due to operational differences and complexities.

Our analysis of prison performance covered the period July 2010 to June 2017. We examined prison incident data for four years, from July 2013 to June 2017.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. In this audit, we used our 'follow-the-dollar' powers, directly engaging the private prison operators and requesting information from them. The private operators cooperated with all our requests.

The cost of this audit was $1 020 000.

1.6 Report structure

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines private prison contract management and performance

- Part 3 examines the safety and security of private prisons

- Part 4 examines prison costs

- Part 5 examines the negotiation of the new private prison contracts.

2 Private prison contract management and performance

The Act requires DJR to monitor the performance of all correctional services to achieve the safe custody and welfare of prisoners. DJR is accountable to the community for the operation and cost of Fulham and Port Phillip. Contracting private companies to operate prisons does not lessen the state's duty of care to prisoners.

The contracts for Fulham and Port Phillip transfer significant operating and financial risks to the private operators and require them to meet specified service standards and performance expectations. These contracts provide the state with broad monitoring and access rights, as well as penalty and intervention options if the operators fail to meet expectations.

This part of the report examines DJR's approach to performance monitoring and the actual performance results for Fulham and Port Phillip. The performance of the private operators needs to be considered in the broader context of the challenges facing the entire corrections system, outlined in Parts 1 and 3.

2.1 Conclusion

GEO and G4S largely met the state's service delivery expectations for correctional and accommodation services over the life of the original contracts for Fulham and Port Phillip.

CV rigorously monitors the performance and contractual compliance of the private operators. It works collaboratively with the private operators to improve their performance and applies contractual penalties in response to serious performance concerns.

CV collects a large amount of data on prison performance, however outdated information systems limit its ability to produce meaningful analysis. CV's limited public reporting on prison performance restricts the transparency and public scrutiny of the prison system.

2.2 CV's scrutiny of operator performance

CV has multiple ways of gaining insight into and scrutinising the operational practices and performance of the private operators—see Figure 1J in Part 1. Reliable and accurate performance data and effective contract management is crucial for CV to meet its performance monitoring obligations and to hold private prison operators to account.

Contract management branch

CV's contract management branch (CMB) is responsible for managing the contract for each private prison. CMB's key functions include:

- assessing the operators' service delivery against requirements

- managing the state's oversight of the prisons' operations manuals and ensuring effective review of operating instructions

- managing the process for authorising private prison staff under the Act

- managing and monitoring prisons' reporting requirements and preparing reports for the Commissioner on prison performance

- validating and verifying performance data reported by the prisons

- managing contract variations, including analysis of operators' proposals to ensure a value-for-money outcome

- managing payments to private operators under the contracts, including payments linked to performance.

CV is efficiently administering its contract management responsibilities. Since our 2010 audit Management of Prison Accommodation Using Public Private Partnerships, CV has increased resources in CMB including a dedicated contract manager for each private prison. It also implemented a new information management system for contract administration. CMB works collaboratively with the private operators and has a strong presence at both private prisons.

Operating instructions in private prisons

Operating instructions guide day-to-day operations in the private prisons. Prison safety and security rely on their effective implementation.

The Commissioner reviews and endorses operating instructions submitted by the private operators. In 2012, CMB began supporting the Commissioner's reviews by checking operating instructions to ensure their consistency with contractual, legal and other requirements and to gain assurance about private prisons' operations. Prior to this, CV conducted an annual high-level review of the prisons' operating manuals.

We examined endorsement processes for 114 operating instructions and found that the review process is rigorous. There were some minor record-keeping issues identified in 12 of the processes.

CMB undertakes regular audits to test the implementation of operating instructions. The audit schedule and methodology is risk based and, importantly, these are not desktop audits—they involve CMB staff talking to staff and prisoners, observing day-to-day prison operations, and checking source documents and registers. Prison management must immediately rectify any critical noncompliance. There is no equivalent audit program in public prisons.

Contractual responses to poor performance

The initial contracts enabled the state to address poor operator performance by:

- reducing the fees operators received for accommodation and/or correctional services if any services were not satisfactory

- reducing the annual performance-linked fee, a payment based on the state's assessment of the operator's performance against the SDO performance thresholds

- issuing default notices

- ending the contract and appointing a new operator if an operator was no longer capable of operating the prison satisfactorily, or if it became insolvent.

Imposing contractual sanctions is not necessarily an appropriate first response to poor performance by the operators. This is particularly so when system-wide challenges and risks, outside the control of individual operators, contribute to performance failures. CV's approach of applying graduated contract responses provides notice and time for the operators to improve their performance. For example, in early 2017, CV responded to a number of serious assaults at Port Phillip with a peer review to assist the operator to improve safety and security. Section 2.5 includes more information on the peer review process and results.

Figure 2A shows the default notices for correctional services issued to the operators of Fulham and Port Phillip, between 1997 and 2017. While public prisons are not subject to contractual defaults or similar processes, it is important to note that similar serious incidents also occur in public prisons.

Figure 2A

Contractual defaults at Port Phillip and Fulham

|

Period |

Incident |

|---|---|

|

Port Phillip |

|

|

1997–2006 |

|

|

April 2016 |

|

|

July 2016 |

|

|

March 2017 |

|

|

Fulham |

|

|

April 2016 |

|

|

August 2016 |

|

Source: VAGO based on information from CV.

Default notices trigger a requirement for operators to develop 'cure' or improvement plans within specified time periods. CV reviews the adequacy of these plans and is rigorous in tracking operator actions to implement the agreed improvement plans through onsite validation and monitoring at the quarterly performance meetings.

Determining performance against SDOs

The private prison operators self-report performance against SDOs to CV, and CV then determines the performance outcomes. The operators' initial reports can change over time based on the outcome of other processes and investigations, including:

- data adjustments initiated by operators following their own review processes, investigation of particular incidents and finalisation of pending drug test results

- validation reviews of operator performance data by DJR

- coronial investigations into deaths in prisons which can extend over years

- determinations issued by the Commissioner based on detailed examination of particular incidents.

This means that there is often a delay between the reporting of an incident and finalisation of the performance outcome for a particular SDO. As an example, the SDO relating to assaults on prisoners by prison staff requires the prison operator to refer the incident to Victoria Police and investigate the alleged assault to either prove or dismiss the allegation. Port Phillip reported no assaults by staff on prisoners in 2010–11. CV later assessed Port Phillip as failing this SDO following an OCSR review of an incident.

The new contracts address the lengthy delays in determining contractual outcomes for prisoner deaths by allowing the Commissioner to issue a financial penalty, known as a 'charge event', when the Commissioner has sufficient information to establish that the operator's failure to meet contractual requirements contributed to the death. The Commissioner does not need to wait for a coroner's finding or other investigations to issue a charge event for a prisoner death.

The Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner also receive requests from both public and private prisons for special consideration when they assess final performance against particular SDOs. This is often the case for SDO 3 (out-of-cell hours). Consistent with the SDO guidelines, prison operators regularly request retrospective approval from the Deputy Commissioner for instances where they have restricted prisoners to their cells or units, known as a 'lockdown'. The Deputy Commissioner must decide whether the request is reasonable—for example, after a serious incident to maintain safety—and, if the request is approved, CV excludes the lockdown from SDO calculations.

CV gave both operators time to phase in the use of a new method for measuring performance against SDO 23 (case management) in 2016–17. This is because CV had imposed a new measurement tool for use across the system without properly considering the contractual implications for the private operators—see Appendix C. This situation demonstrates how important it is for CV to consider the contractual implications of any planned substantive changes in system-wide standards, initiatives or performance measures.

CV's oversight of occupational health and safety performance

Victoria's Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 and associated regulations provide the framework for ensuring a safe workplace. In the context of prisons, the obligation for ensuring the health and safety of workers, prisoners and others resides with the employer, in this case G4S and GEO. However, the contracting of correctional services to private operators does not completely remove the state's obligations under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

Although CV has an SDO measuring occupational health and safety (OHS) performance, it does not apply it to private prisons. We found that CV had minimal oversight of the private operator's OHS performance. In addition, CV did not collect key information on how the private operators manage their OHS obligations, for example, the number of notices issued by WorkSafe Victoria under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

We raised these issues with CV during the audit and it has now increased the OHS reporting requirements for private prisons. This is a positive step to improve CV's oversight and better understand whether private operators are meeting their OHS obligations.

2.3 Prison performance data

Accurate and reliable performance data is important for transparent reporting on prison operations and costs. We reviewed CV's processes to obtain assurance on the accuracy and completeness of this data, with a focus on safety and security performance data.

Validation of incident data

The Prisoner Information Management System (PIMS) is CV's system for recording incidents in Victorian prisons. In 2016–17, there were 24 335 incidents recorded in PIMS for the men's prison system, a rate of 3.8 incidents per prisoner. This has increased from 10 400 incidents recorded in 2010–11, a rate of 2.4 per prisoner. Of the 2016–17 incidents, 5 per cent were notifiable, that is, the most serious incidents, described further in Part 3.

Every incident entered into PIMS, across both public and private prisons, is classified according to the nature and severity of the incident. CV staff manually check the details of each incident, which provides assurance that incidents have been accurately classified and recorded. It is important for the private operators to classify incidents correctly because many of the incidents recorded in PIMS are relevant for assessing the operator's performance which, in turn, has financial implications for the state and the operators.

Between December 2016 and May 2017, Port Phillip had 272 incidents which required reclassification (9.1 per cent of its incidents), and Fulham had 133 incidents (8.1 per cent of its incidents). System-wide in men's prisons, 8.7 per cent of incidents required reclassification. Reclassification of PIMS incidents does not always mean there is an error. Rather, the classification may change if further information becomes available, for example, a prisoner requiring hospital admission after an incident.

SDO data validation

CV regularly validates the SDO performance data self-reported by the private prison operators to ensure the accuracy of the results.

To do this, CV visits each prison and checks a sample of reported SDO data against source records. These records include the daily logbooks held in every prison accommodation unit, training and work attendance registers, and lab reports supporting urinalysis results.

CV is introducing a new approach to its validation of SDO data for public and private prisons in response to an external review that it commissioned in 2016. The review found that:

- there was too much focus on data verification, rather than data and trend analysis

- the length of time taken to collect, report and verify data prevented real‑time responses to issues

- prisons should assume more responsibility for data accuracy

- there was inconsistency in validation efforts across public and private prisons

- a streamlined data collection method was required because of the different data systems in use

- there was a need for a new risk-based validation method.

A CV reform project intends to establish a new risk-based methodology for validating self-reported data, including the frequency of validation required. The new contracts also include KPIs related to data accuracy, which shifts responsibility to the private operators.

Initial contracts

Under the initial contracts, the former OCSR validated SDO data annually. CV took over responsibility for data validation in 2015–16 and now performs monthly validation checks.

CV's validation of Port Phillip's SDO data for 2015–16 resulted in changes to reported performance data for five SDOs. The validation of Fulham's SDO data for 2015–16 resulted in changes to reported performance data for three SDOs. The changes did not affect the overall pass or fail rate of either prison.

CV's SDO calculator

CV's SDO calculator is a complex macro-driven Excel spreadsheet developed as the primary analytical tool to generate SDO and KPI performance reporting across all prisons. The spreadsheet performs both data storage and calculation. We reviewed the 2015–16 SDO calculator and found that it accurately computed the performance outcomes based on the input data.

However, there are numerous procedures required to manually input, verify and modify the source data. We are also concerned that the SDO calculator is highly customised, with complex design and bespoke back-end scripting. While there are basic usage guides in place and staff who are familiar with its operation, the primary capability and knowledge of the design and coding behind the calculator is limited to a single CV employee.

This dependence on one staff member potentially creates a single point of failure for the entire SDO performance reporting process. In addition to this, there are risks of untracked data changes to the data and issues with the functionality of the data.

Data analysis

Easy access to and effective use of relevant and reliable data is critical for CV to make informed decisions about current risks, emerging trends, operational requirements and strategic planning decisions in the corrections systems. A 2016 review of CV's SDO validation and review process found that CV has limited time to undertake meaningful analysis for the quarterly performance meetings.

CV regularly collects a significant volume of data on the operation and performance of both public and private prisons. However, the various information systems do not easily facilitate data analysis and the multiple systems do not readily interface, making it difficult to integrate data and produce meaningful analyses.

|

E*Justice holds a range of prisoner information and overlaps with PIMS. It records prisoner risk ratings, daily counts of prisoners (musters) and prisoner movements among other important information. Victoria Police uses E*Justice data via a different interface. |

Consistent with our previous audits Managing Community Corrections Orders (2017) and Administration of Parole(2016),we found that CV's data is managed across several divisions and is contained in disparate legacy systems. Data is stored in CV's two main systems—PIMS and E*Justice—as well as over 200 locally managed 'shadow systems' such as Excel spreadsheets. Vendor technical support has expired for both PIMS and E*Justice.

There are clear opportunities to improve CV's data analytics capability, to better understand the performance challenges facing the prison system. For example, using data analysis to identify trends and potential correlations between prisoner profiles, the proportion of prisoners with psychiatric conditions, and incident trends would help CV to develop strategies for managing risks, particularly the higher instances of violence across the system. Another example is CV's current inability to analyse and use data to produce evidence on the impact of 'double-bunking' on prison incidents and risks. Double-bunking is when a cell designed for single occupancy is changed to accommodate two prisoners on a set of bunks.

We have seen isolated evidence of recent proactive data analysis by CV. For example, in August 2017, CMB analysed data at Port Phillip and found a potential correlation between 'shivs' (improvised knives) and the number of positive urinalysis results and tobacco-related incidents in the same location. As a result, CMB issued a contract administration note requiring Port Phillip to develop and implement mitigation strategies. Port Phillip provided an action plan to monitor and mitigate these issues, and CMB is monitoring its ongoing implementation.

CV recognises the weaknesses of using outdated legacy systems. However, it has been unsuccessful in securing funding for its preferred replacement—an integrated offender management system. In lieu of an integrated system, CV has developed an Excel-based incident-analysis tool that integrates some of the data between PIMS and E*Justice. The private prison operators find this tool valuable as it allows them to interrogate incident data in detail.

2.4 Prison performance reporting

Performance analysis and discussions

CV meets quarterly with the private prison operators to consider a wide range of performance information and data. These meetings are open and collaborative. They identify key issues and trends, and allow CV to hold the operators to account for their performance. CV also provides the Commissioner with a monthly report highlighting key performance data and trends.

In 2014, CMB implemented the Private Prison Reporting Framework (PPRF) to capture a range of data not directly related to SDOs or KPIs. The PPRF provides CV with greater oversight of prison operations and performance, including the following information:

- workforce data—sick leave, staff turnover, staff disciplinary actions

- prisoner movement data

- prison searches for contraband and drugs

- prison visits

- prisoner disciplinary processes.

CV also contributes information to the PPRF, including the results of operating instruction and other compliance audits. The PPRF allows CV and the prisons to consider a broader range of information when monitoring and analysing trends.

Public reporting on private prisons

Transparent public reporting on the performance of the prison system is important for making DJR and private prison operators accountable and for building public trust in the system.

The limited information reported in DJR's annual report and Budget Papers provides little real insight into the operation of the prison system and no detailed information on the relative performance of individual prisons, including private prisons. The exception to this is the detailed performance information that DJR publishes on urinalysis drug results in individual prisons.

There is limited Victorian public reporting on private prison contracts, operations and performance. Other jurisdictions provide more detailed information, for example, the Department of Corrective Services in Western Australia publishes an annual report on the performance of each private prison, including detailed information about its service and financial performance.

Aside from ad hoc reviews or investigations by other integrity bodies such as the Victorian Ombudsman, there is very limited information in the public domain about the performance of private prison operators. JARO reports are not publicly available because they provide internal assurance rather than external oversight. Western Australia and New South Wales have independent inspectorates that monitor prisons and report publicly on this work. There is limited public transparency about the performance of Victoria's prisons.

In 2014, DJR and DTF advised government that they would work together to identify more suitable Budget Paper 3 measures to improve the transparency of the corrections system. To date, there have been no significant changes to those measures. CV advises that it is currently working on options to improve performance measures but that their implementation is dependent on a new integrated offender management system.

Australia's ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) in December 2017 will increase the scrutiny of all places of detention in Victoria, including prisons. OPCAT is an international human rights treaty that aims to prevent abuse of people in detention by opening these places up to independent inspections by United Nations experts and independent local inspection bodies. Victoria is yet to finalise its implementation of OPCAT, but the November 2017 Victorian Ombudsman report Implementing OPCAT in Victoria: Report and inspection of the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre demonstrates the increased public scrutiny that all prisons should expect.

2.5 Performance results

GEO and G4S largely met the state's service delivery expectations for correctional and accommodation services over the life of the original contracts for Fulham and Port Phillip.

Accommodation services

The private operators met the state's requirements for accommodation services over the life of the initial contracts. However, these contracts included no SDOs directly related to facilities maintenance and specified only high-level obligations for repair and maintenance. The contracts required the operators to keep the facilities 'in good and substantial repair and condition' but did not define what this meant.

DJR advised government during negotiations for the new contracts that the assets and facilities at Port Phillip and Fulham were structurally sound and fit for purpose. DJR provided this advice based on its detailed asset condition surveys that also identified many defects in the facilities. The defects were rectified prior to commencement of the new contracts at the operators' expense, or under the new contracts as part of the asset life cycle management regime funded by the state.

Port Phillip's SDO results and performance payments

G4S has consistently underperformed at Port Phillip against the state's expectations between 2010–11 and 2016–17 in three key measures:

- SDO 2—prisoner assaults on staff or other persons

- SDO 6—prisoner-on-prisoner assaults

- SDO 8—positive urinalysis results.

See Part 3 for more information on these performance results.

Figure 2B shows G4S's performance in meeting SDO thresholds since 2010–11 and the performance payment outcomes for each year.

Ten of Port Phillip's SDOs in the old contract require 100 per cent compliance and failure can result from a single instance of noncompliance, regardless of the overall performance rate.

Figure 2B

Port Phillip SDO performance

|

Year |

SDO thresholds achieved |

Failed SDOs |

Performance payment outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2010–11 |

17 of 19 |

|

Reduced by 3 per cent |

|

2011–12 |

15 of 19 |

|

Reduced by 13 per cent |

|

2012–13 |

18 of 21 |

|

Full performance payment |

|

2013–14 |

16 of 22 |

|

Reduced by 22.5 per cent |

|

2014–15 |

19 of 22 |

|

Reduced by 3 per cent |

|

2015–16 |

18 of 22 |

|

Reduced by 17 per cent |

|

2016–17 |

17 of 21 |

|

Reduced by 20 per cent |

Source: VAGO based on information from CV.

G4S has only received the full performance payment once in the last seven years. There are a number of examples where CV has worked cooperatively with G4S to address its performance.

CV regularly meets with G4S to discuss performance, both formally and informally. Along with these structured and ad hoc conversations, there have been two occasions since mid-2014 when the Commissioner has formally 'called in' Port Phillip management to discuss particular concerns about its operational performance.

G4S responded to CV's concerns, whether raised formally or informally, by developing strategies and plans. CV rigorously monitored the implementation of agreed actions.

CV's increased oversight and scrutiny of private prisons is positive, however it is not possible to determine whether it has resulted in improved performance, as CV and the prison operators do not routinely evaluate the outcomes and impacts of their improvement strategies. Section 3.5 discusses an example of this relating to violence-reduction strategies.

In May 2017, after an escalation in serious incidents, G4S agreed to a peer review process at Port Phillip initiated by CV, designed to review the current operations and identify areas for improvement. This collaborative process sought to identify issues and share lessons learnt from the broader prison system. Through the process, CV's subject-matter experts and management from other prisons reviewed a range of different areas including:

- the spread and effectiveness of middle management

- barrier and perimeter security

- prisoner cohort management, including placement and vacancy management

- management of external escorts

- culture, including staff and prisoner interactions

- training, including for new recruits, refresher training, de-escalation, use of force and incident management

- compliance management

- implementation of the action plan to improve Port Phillip's PIU.

The reviews completed to date identified some areas of positive performance, including the management of visits, external escorts and the relationship between the prison and CV's sentence management function. They also identified about 40 areas for improvement, which included:

- communication between management and general duties staff

- development of supervisors, availability of supervisors in the unit and visibility of senior management

- balancing compliance and prisoner management activities

- use of resources in the PIU, particularly dog handlers and staff escorting prisoners outside of the prison

- development and succession planning for staff.

It is positive to see Port Phillip and CV working together to identify issues and share the lessons learnt across the system.

Fulham's SDO results and performance payments