Sexual Harassment in the Victorian Public Service

Overview

Sexual harassment is harmful, unlawful and, in some instances, a criminal offence. Its impact on individuals and organisations can be significant.

We examined whether the Victorian public service provides workplaces that are free from sexual harassment. We looked at whether all eight departments effectively prevent, report and respond to sexual harassment.

VAGO acknowledges that we are not immune to the issues faced by the broader public sector, including sexual harassment. To see our results of the People Matter Survey for 2019, please click here.

Transmittal letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2019

PP No 97, Session 2018–19

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Sexual Harassment in the Victorian Public Service.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

28 November 2019

Acronyms and abbreviations

Acronyms

| AHRC | Australian Human Rights Commission |

| APS | Australian Public Service |

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| DJPR | Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

| DoT | Department of Transport |

| DPC | Department of Premier and Cabinet |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| EAP | Employee Assistance Program |

| HR | human resources |

| IPP | Information Privacy Principle |

| LGBTIQ | lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, intersex, queer and questioning |

| PMS | People Matter Survey |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VEOHRC | Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission |

| VPSC | Victorian Public Sector Commission |

| VSB | Victorian Secretaries Board |

Abbreviations

| the enterprise agreement | Victorian Public Service Enterprise Agreement 2016 |

| the guide | VPSC Guide for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace |

| the model policy | VPSC Model Policy for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace |

Support options

Sexual harassment can take many forms and result in physical and emotional harm. Our report discusses these issues. If you or someone you know has experienced sexual harassment or assault, or feels distressed, several support options are available.

1800RESPECT—national sexual assault, domestic and family violence counselling service

1800RESPECT provides information, referral and counselling services to people experiencing or at risk of experiencing sexual assault, domestic or family violence. It is also available to friends, family and professionals. 1800RESPECT provides a confidential service 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Phone: 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732)

Employee Assistance Program

The Employee Assistance Program (EAP) provides free and confidential short‑term counselling to Victorian Public Service employees for workplace and personal issues. Staff can obtain details of the relevant EAP from their departments' human resources (HR) teams.

Centres Against Sexual Assault

Centres Against Sexual Assault are non-profit, government-funded organisations that provide support, counselling and crisis care to child and adult victims of sexual assault and their family. You can find your local centre by visiting www.casa.org.au.

Lifeline

Lifeline is a national charity providing all Australians experiencing a personal crisis with access to 24-hour crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Phone: 13 11 14

Making a sexual harassment complaint

This audit examines whether the Victorian Public Service is free from sexual harassment. We do not take or investigate individual complaints. You can make a complaint or seek further information from:

Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission

The Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) is an independent statutory body that has responsibilities under several pieces of legislation, including the Equal Opportunity Act 2010. You can contact VEOHRC to seek information or have your complaint heard.

VEOHRC may review complaints or refer them to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Phone: 1300 292 153

www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au

Australian Human Rights Commission

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) is an independent statutory organisation established by the Parliament of Australia. It promotes human rights in Australia and internationally and investigates complaints about discrimination and human rights breaches.

Phone: 1300 656 419

Victoria Police

The role of Victoria Police is to serve the Victorian community and uphold the law. If you have experienced or witnessed a criminal offence, you should report it to Victoria Police via a local police station. In an emergency, dial 000.

Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal

The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal hears and decides civil and administrative legal cases in Victoria. Complainants can apply directly to the tribunal to have a complaint about sexual harassment heard.

Phone: 1300 018 228

Audit overview

Sexual harassment is harmful, unlawful and, in some instances, a criminal offence. Its impact on individuals and employers can be significant.

The Equal Opportunity Act 2010 defines what behaviours constitute sexual harassment in public life, including in the workplace. Sexual harassment is unwelcome behaviour of a sexual nature that a reasonable person would expect would make another person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated. Anyone can perpetrate or experience sexual harassment. It may be physical, spoken or written and can occur even when the perpetrator does not intend it.

Under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, organisations including Victorian government departments must take reasonable and proportionate measures to eliminate sexual harassment in their workplaces.

This audit examines whether Victorian government departments provide workplaces that are free from sexual harassment. The departments are:

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP)

- Department of Education and Training (DET)

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)

- Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS)

- Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR)

- Department of Transport (DoT)

- Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC)

- Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF).

We looked at whether departments:

- have effective measures to prevent and report on sexual harassment

- respond to complaints of sexual harassment in a fair and effective manner.

Conclusion

|

The PMS is an annual survey run by the Victorian Public Sector Commission. It invites all employees in participating Victorian public sector organisations to have their say on how well their organisation, leaders and colleagues demonstrate public sector values and employment principles. |

No department is free from sexual harassment and while they are working to improve this, departments can still do more. While departments express a clear message that sexual harassment is unacceptable, the 2019 People Matter Survey (PMS) found that one in 14 respondents experienced sexual harassment in the previous 12 months.

Departments make complaint channels available, but staff rarely use them. Our survey of public service staff found that this is because staff lack faith in the complaints system, fear the consequences, or perceive that the behaviour they experienced is not serious enough. Departmental training currently does little to address this.

Managers are often the ones to handle informal complaints of sexual harassment within their team, yet few receive training to help them do this. Further, departments do not generally have oversight as to how informal complaints are managed.

We reviewed formal complaints and found that for most, the departments' complaint handling process was fair and effective. However:

- The process for dealing with formal complaints can be lengthy and is not transparent.

- Departments have differing views and practices as to what information they can share with the complainant about investigations, which can lead them to share very little.

- We also saw differences between departments' threshold for investigating and making findings of misconduct, as well as examples of poor record keeping.

Poor handling of both formal and informal complaints leads to staff dissatisfaction, negative impacts on complainants and others and may also lead to organisational liability.

Findings

Prevalence of sexual harassment

Through the PMS run by the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC), departments have data on the prevalence of sexual harassment in their workforce. The survey is anonymous, which encourages staff to be open about their experiences. Response rates at departments are high (between 43 and 82 per cent), which means the data is reliable.

In the 2019 PMS, 7 per cent of departmental respondents said they had experienced sexual harassment in the past 12 months. This is more than 1 400 employees.

This has reduced from 11 per cent of respondents in the 2016 survey, which is positive. However, it is too soon to determine if this decrease is a trend, as only four years of data is available.

Employees at high risk

Anyone can experience sexual harassment, but the PMS results show that the following types of respondents are at much greater risk:

- those with a self-described gender identity (26 per cent experienced sexual harassment)

- women aged 15 to 24 (14 per cent experienced sexual harassment)

- lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, intersex, queer and questioning (LGBTIQ) persons (13 per cent experienced sexual harassment)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (12 per cent experienced sexual harassment)

- those who earned less than $75 000 (11 per cent experienced sexual harassment).

Types of sexual harassment experienced

Sexual harassment can take many forms. However, the 2019 PMS reports that the most common experiences were:

- intrusive questions about a person's private life or comments about their physical appearance

- sexually suggestive comments or jokes that offend a person (either in a group or one-on-one situation).

Departments must address all forms of sexual harassment, as research has shown that these behaviours can have significant negative impacts on individuals.

Negative impacts

Sexual harassment can significantly affect employees' mental and physical health. We conducted our own survey of departmental employees and received 4 811 responses. Twelve per cent of respondents who experienced sexual harassment said it negatively affected their:

- mental health and caused them stress

- self-esteem and confidence

- employment, career or work

- relationship with their partner, children, friends or family.

For organisations, sexual harassment may reduce workforce morale, and increase absenteeism and turnover. It can also expose departments to legal liability and be costly to investigate.

Responding to complaints

Encouraging complaints

Departments have adequate processes to accept complaints, but they need to do more to address underreporting of sexual harassment.

Of the PMS respondents who said they experienced sexual harassment, only 3 per cent said that they made a formal complaint.

Our survey suggests that the top reasons why staff do not make complaints about sexual harassment are that they:

- did not think it was serious enough

- believed there would be negative consequences for their reputation and career

- did not think it would make a difference

- did not believe the complaint would result in any action.

While some departments have implemented strategies to encourage staff to report complaints, it is too soon to assess whether this has improved reporting.

Informal and formal responses

Departments have both formal and informal processes to respond to sexual harassment complaints, which is good practice. In some cases, inappropriate behaviour (including sexual harassment) can be addressed at the team or workgroup levels, and not proceed to a formal investigation.

However, when departments address sexual harassment informally, there is little central oversight or knowledge of these instances and their handling. This also meant we could not assess how well departments respond to informal complaints.

Managers are often the ones to respond to informal sexual harassment complaints. There is limited training for managers on responding to sexual harassment complaints, which is a missed opportunity particularly given the sensitivity of these issues.

Departments receive a small number of formal complaints. We found variable practice in how departments handle these complaints. Poor practices include incomplete record keeping and limited communication with complainants, inconsistencies in the handling of potential criminal matters, lack of procedural fairness, and inconsistencies in investigations.

Documentation and record keeping

Departments do not always keep accurate and complete records on how they have handled formal sexual harassment complaints. This ranged from minor to some more serious instances, such as where investigation reports were missing.

Proper record keeping within the case files ensures departments comply with the Public Records Act 1973, and the absence of records puts the department at risk if its decisions are challenged.

Most departments do not have a sophisticated complaints management system. They rely on often outdated, mostly manual systems, which do not allow for easy registration, categorisation and reporting of complaints. Two departments were unable to quantify how many sexual harassment complaints they have received due to a failure to categorise sexual harassment complaints consistently, and having multiple, varied databases for central and regional staff.

Responding to criminal matters

Departments do not have a common understanding about how to handle alleged sexual harassment that may constitute a criminal offence, particularly in relation to engaging with Victoria Police before starting an investigation.

VPSC's guidance states that if an allegation appears to be relevant to the police, the department is obliged to report it to the police regardless of whether the complainant has done so. We found two cases where departments did not do this.

Poor communication with complainants

Making a complaint of sexual harassment can be a stressful experience that can negatively affect an employee's mental health and wellbeing.

Departments providing regular communication and information to the complainant helps complainants to feel part of the process.

We found variable practices in this regard. Some departments provided complainants with a senior officer within the department to offer support. Other departments had limited documentation as to whether they offered support or provided updates on the investigation.

All departments have communicated to their staff about the EAP on their intranet and in policies. In almost half of the investigation files we reviewed, departments did not document offers of support, such as the EAP, to the complainant in their investigation files. As such, we could not confirm that they occurred.

Departments give complainants varying levels of detail on the outcome of investigations, due to concerns for the subject's privacy. There is also limited guidance and uncertainty around how much information can be provided. Our survey highlighted that failure to inform the complainant can result in dissatisfaction in the complaint process.

Preventing sexual harassment

Policies

In November 2018, VPSC introduced the Model Policy for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace (the model policy). In general, departments have clear and accessible policies on sexual harassment that align with VPSC's model policy.

Some policies miss elements that the model policy includes, such as referring to the importance of bystander intervention and outlining external complaint avenues. As the VPSC introduced the model policy in November 2018, departments are still updating their sexual harassment policies to align with it.

DJCS and DTF do not have standalone sexual harassment policies, but instead include it in other documentation, such as appropriate workplace behaviour policies. This may reduce the visibility of sexual harassment guidance.

Training

Departments include sexual harassment training in their staff induction modules, but not all staff have completed this training. Our survey found only 23 per cent of respondents said they completed training on sexual harassment at induction, and 42 per cent said that they had never received sexual harassment training.

This is a missed opportunity to educate staff and may also expose departments to legal liability if sexual harassment occurs.

The content of training is also important. Bystanders play an important role in addressing and preventing sexual harassment, but most departments do not provide detailed training to help bystanders understand their role.

Training is important for managers as well as staff. Respondents to our survey highlighted issues with the way that their managers handled their complaint. Most departments do not offer specialised training for managers on how to deal with sexual harassment complaints.

Communication

At seven of the eight departments, senior leaders have sent at least one communication in 2018 outlining that sexual harassment in the workplace is unacceptable and signalling their commitment to its prevention.

In our survey, 71 per cent of respondents agreed that their department communicates zero tolerance for sexual harassment.

This is positive. Departments should continue to communicate at least annually with staff and express a commitment to eliminate this behaviour in the workplace. They may also consider further, targeted communication based on risk factors.

Addressing risk factors

The PMS gives departments information on high-risk teams, cultures and leadership within their workplace. Most departments prepare action plans to address key PMS findings, but these plans do not focus on groups at higher risk of sexual harassment, such as those with a self-described gender identity, LGBTIQ employees, women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employees.

Recommendations

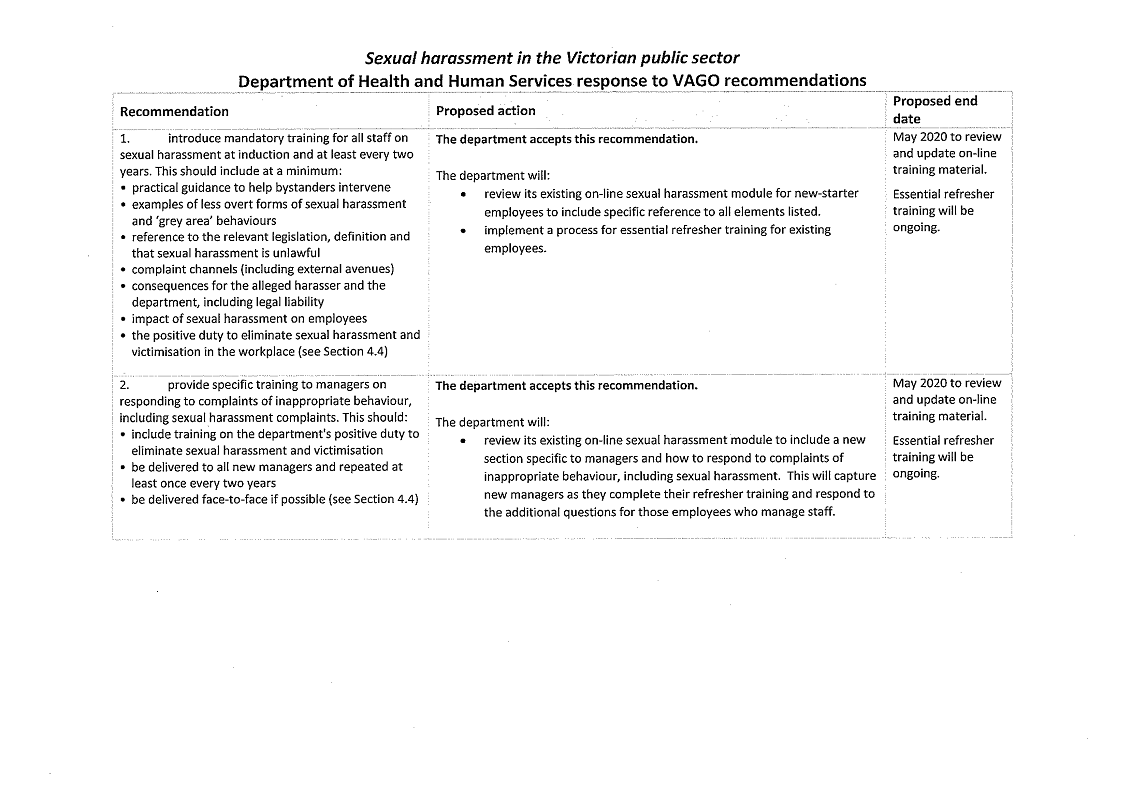

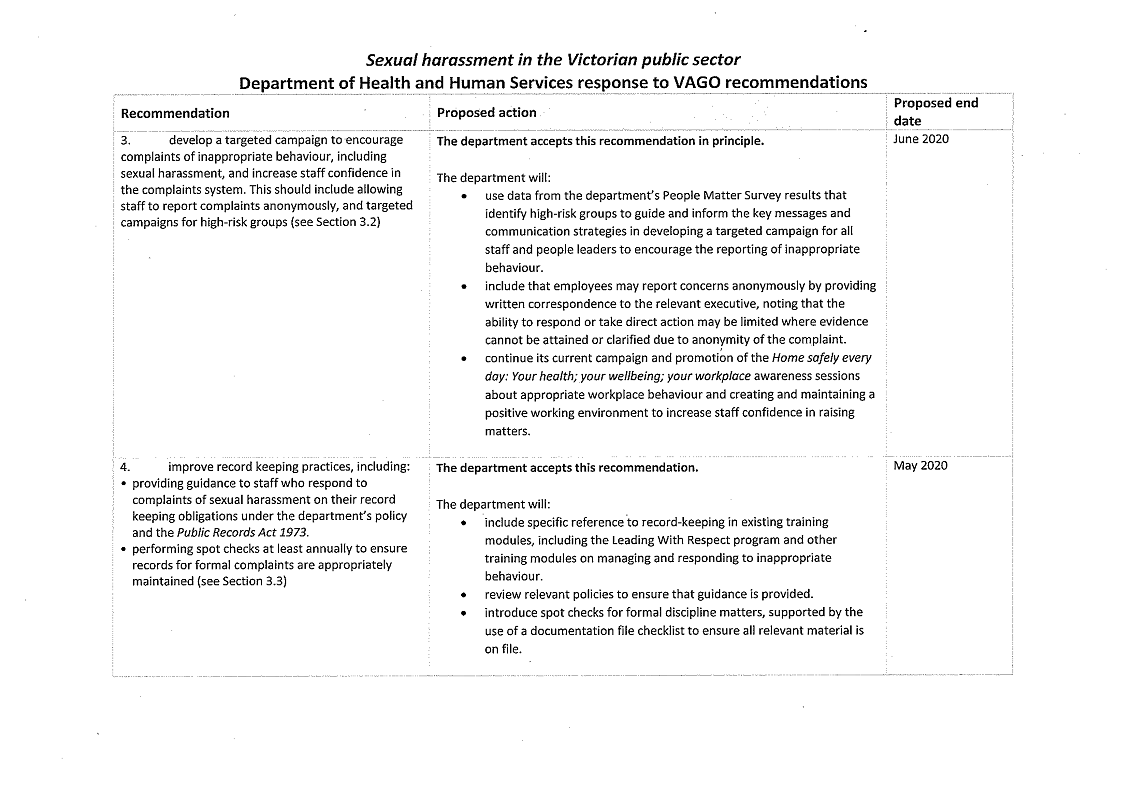

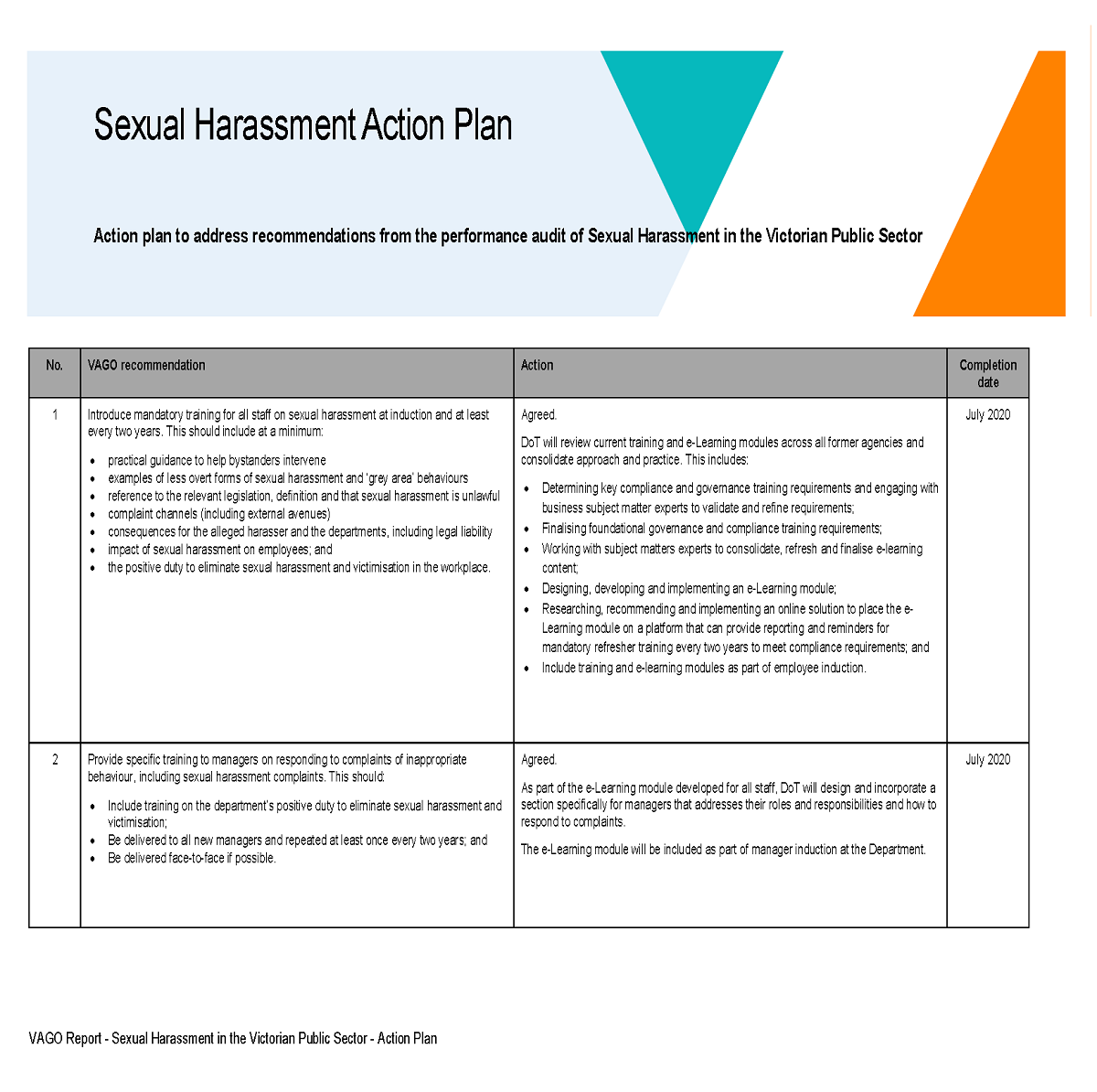

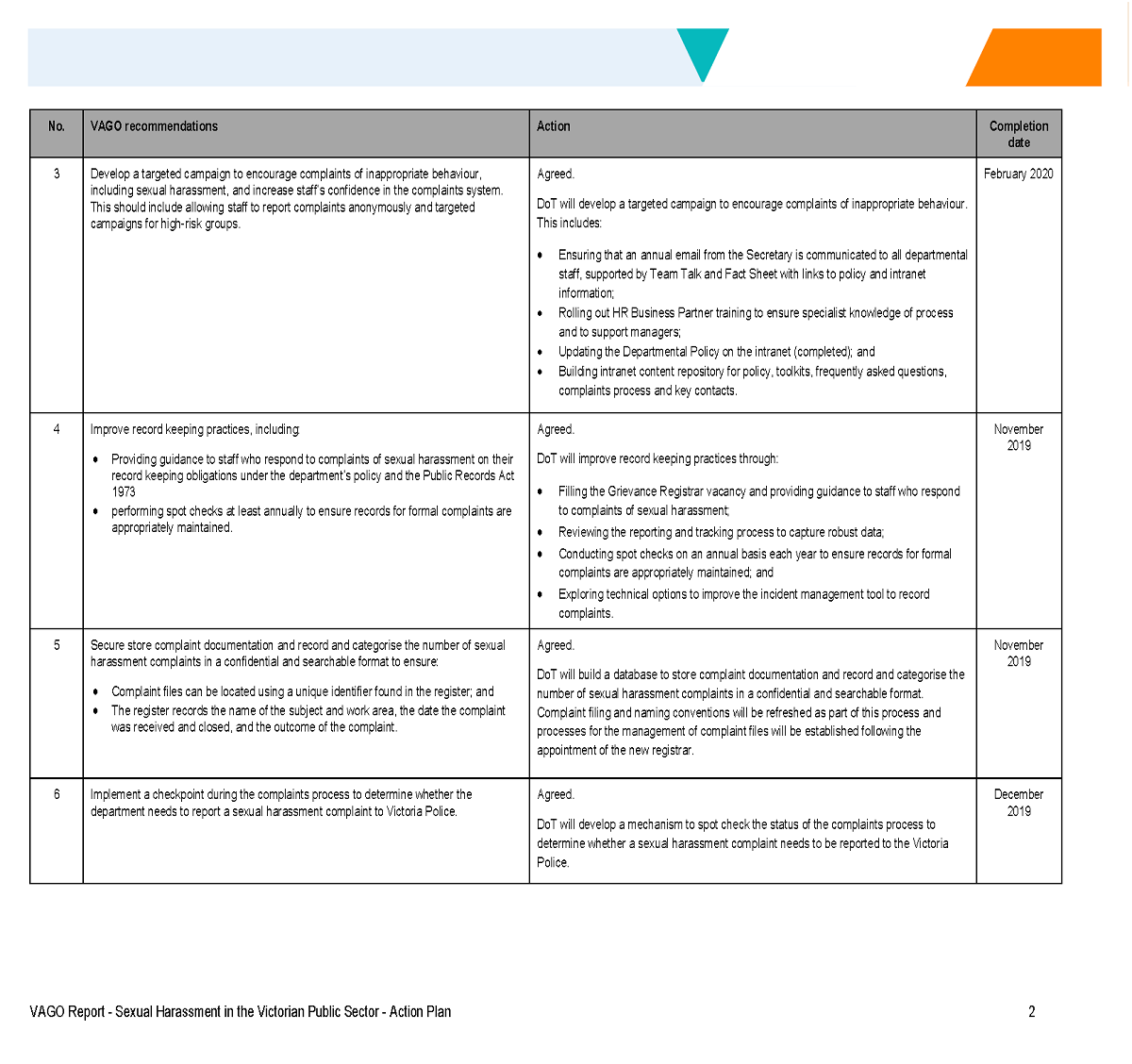

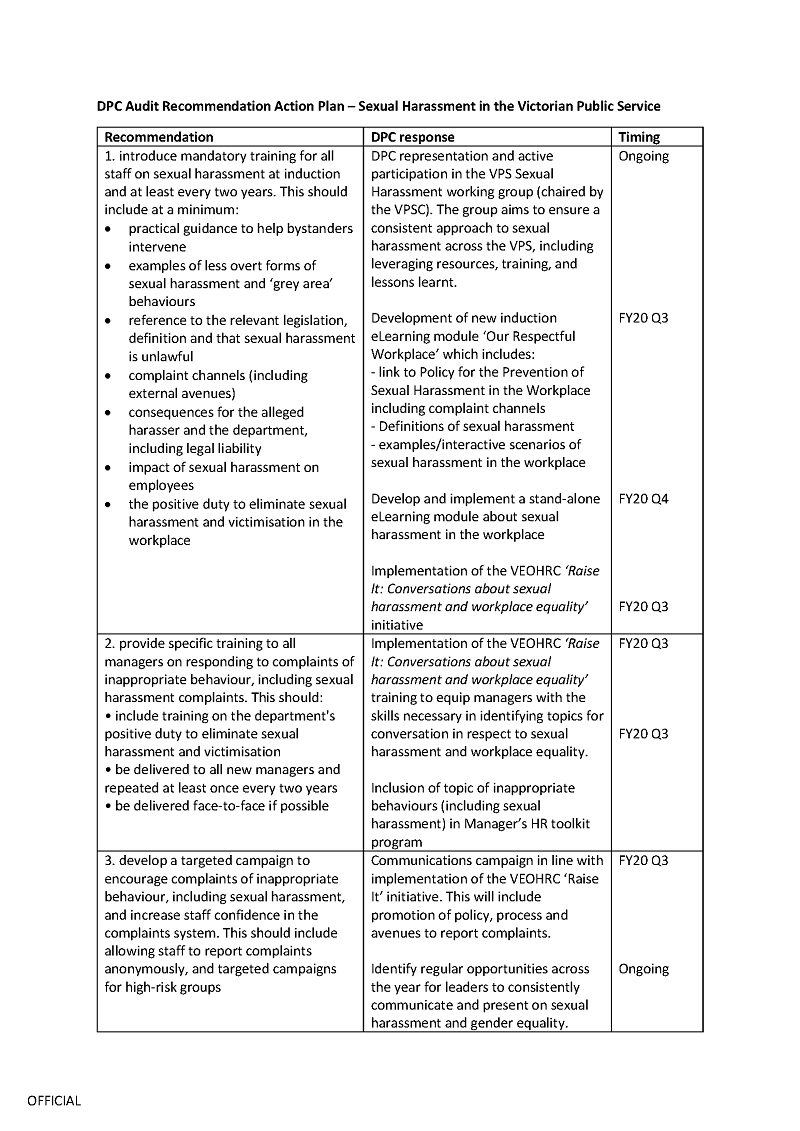

We recommend that all departments:

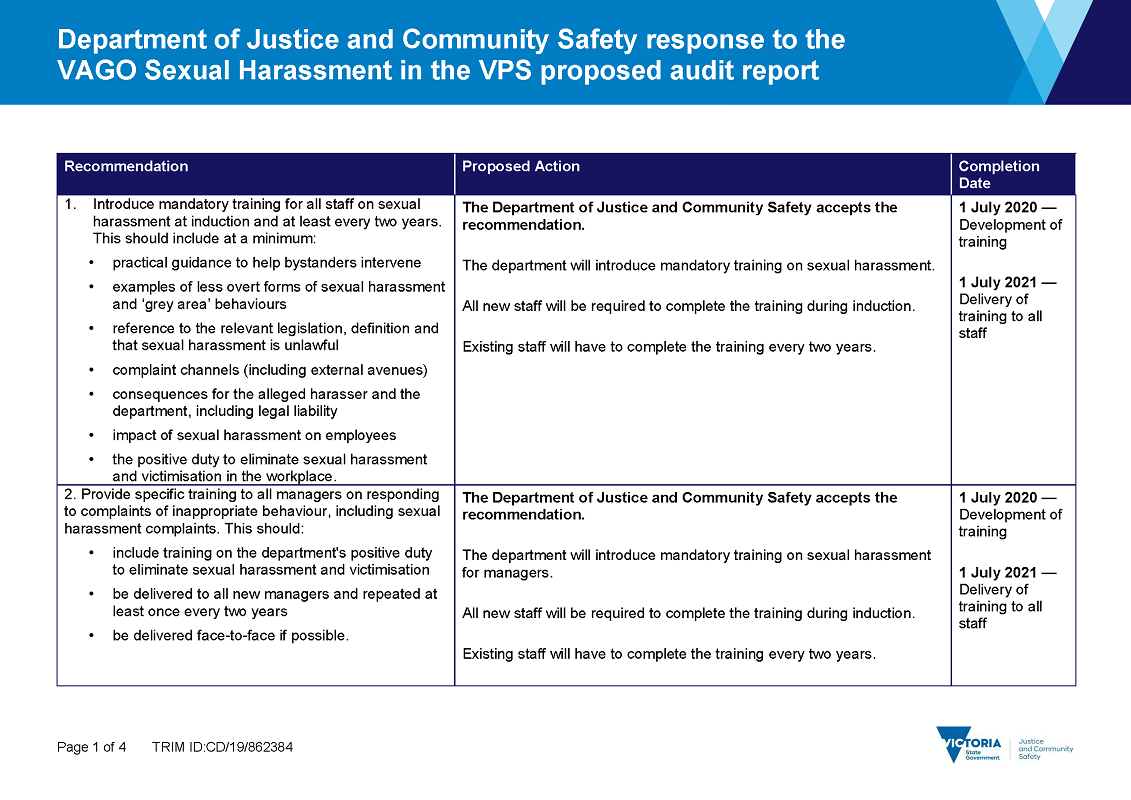

1. introduce mandatory training for all staff on sexual harassment at induction and at least every two years. This should include at a minimum:

- practical guidance to help bystanders intervene

|

Grey area behaviours are behaviours that some employees may find offensive and others may not. These might include more subtle and nuanced forms of sexual harassment. |

- examples of less overt forms of sexual harassment and 'grey area' behaviours

- reference to the relevant legislation, definition and that sexual harassment is unlawful

- complaint channels (including external avenues)

- consequences for the alleged harasser and the department, including legal liability

- impact of sexual harassment on employees

- positive duty to eliminate sexual harassment and victimisation in the workplace (see Section 4.3)

2. provide specific training to all managers on responding to complaints of inappropriate behaviour, including sexual harassment complaints. This should:

- include training on the department's positive duty to eliminate sexual harassment and victimisation

- be delivered to all new managers and repeated at least once every two years

- be delivered face-to-face if possible (see Section 4.4)

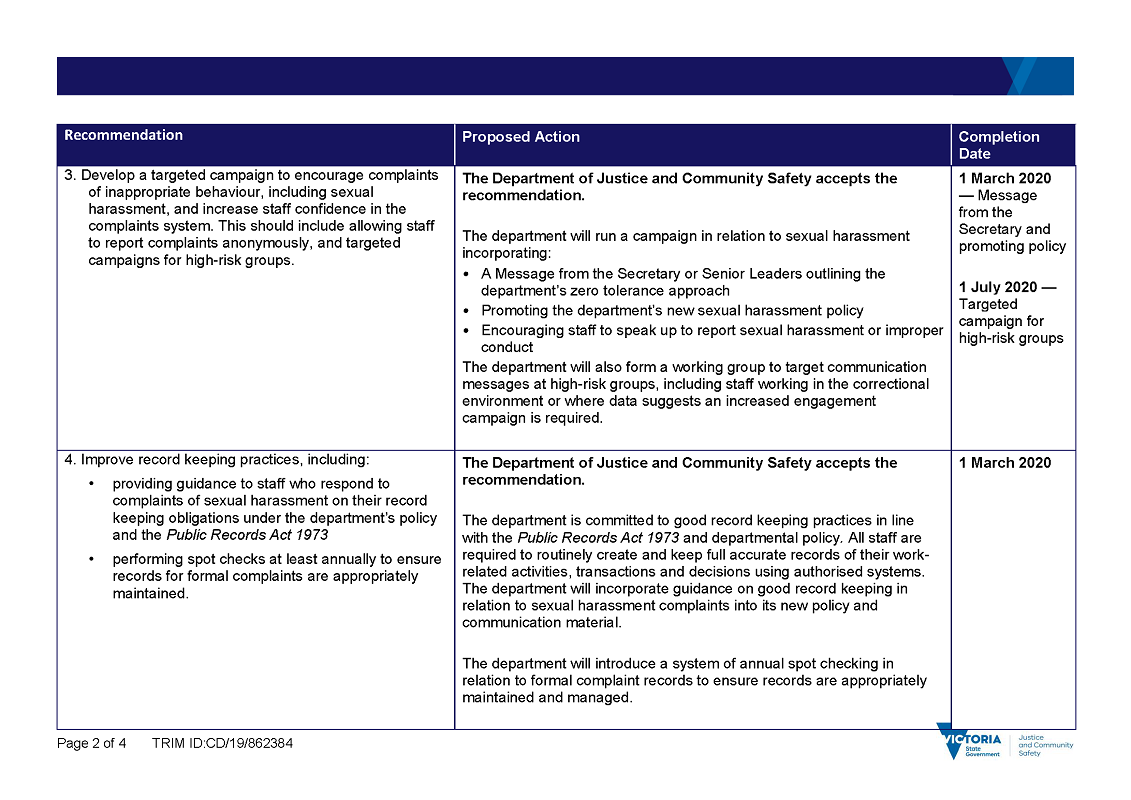

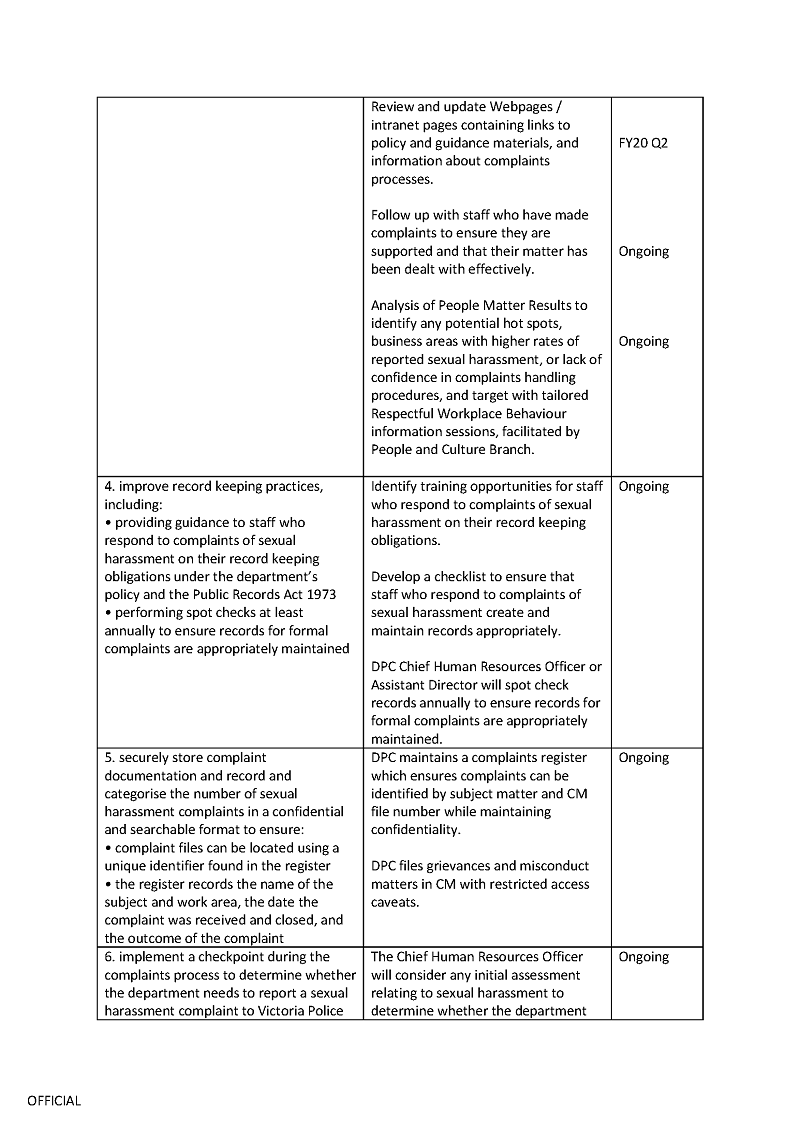

3. develop a targeted campaign to encourage complaints of inappropriate behaviour, including sexual harassment, and increase staff confidence in the complaints system. This should include allowing staff to report complaints anonymously, and targeted campaigns for high-risk groups (see Section 3.2)

4. improve record keeping practices, including:

- providing guidance to staff who respond to complaints of sexual harassment on their record keeping obligations under the department's policy and the Public Records Act 1973

- performing spot checks at least annually to ensure records for formal complaints are appropriately maintained (see Section 3.3)

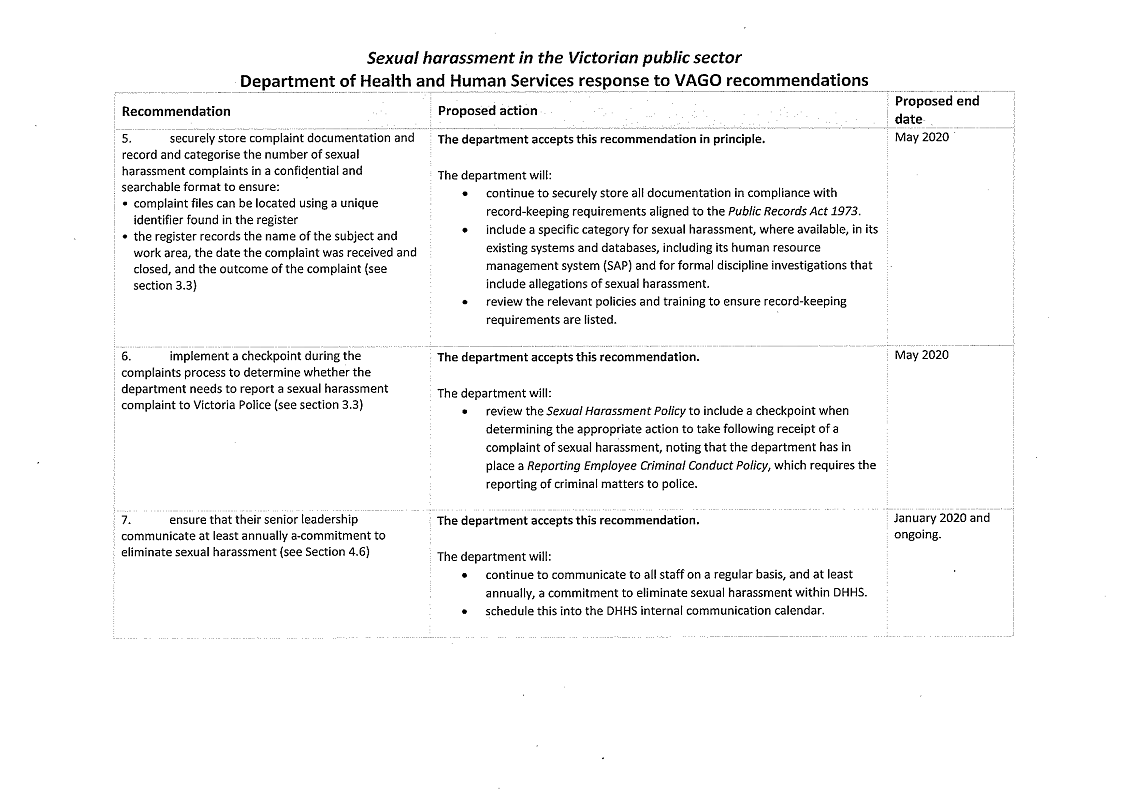

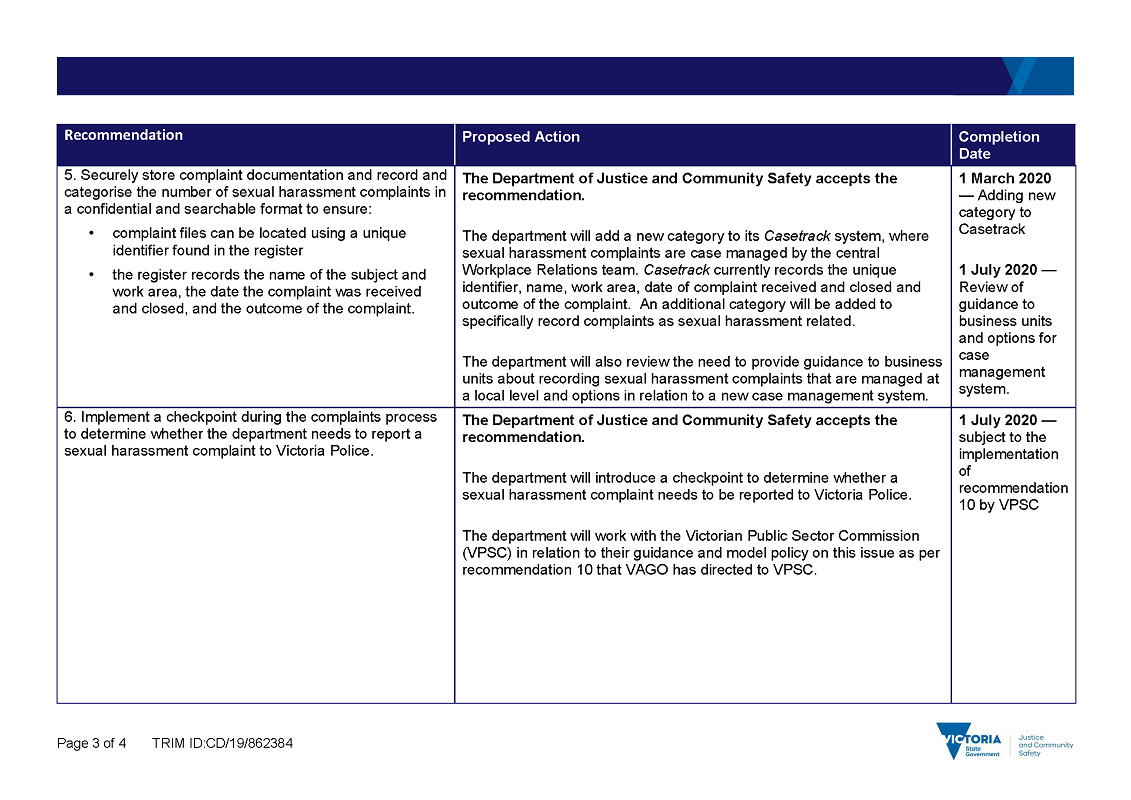

5. securely store complaint documentation and record and categorise the number of sexual harassment complaints in a confidential and searchable format to ensure:

- complaint files can be located using a unique identifier found in the register

- the register records the name of the subject and work area, the date the complaint was received and closed, and the outcome of the complaint (see Section 3.2)

6. implement a checkpoint during the complaints process to determine whether the department needs to report a sexual harassment complaint to Victoria Police (see Section 3.3)

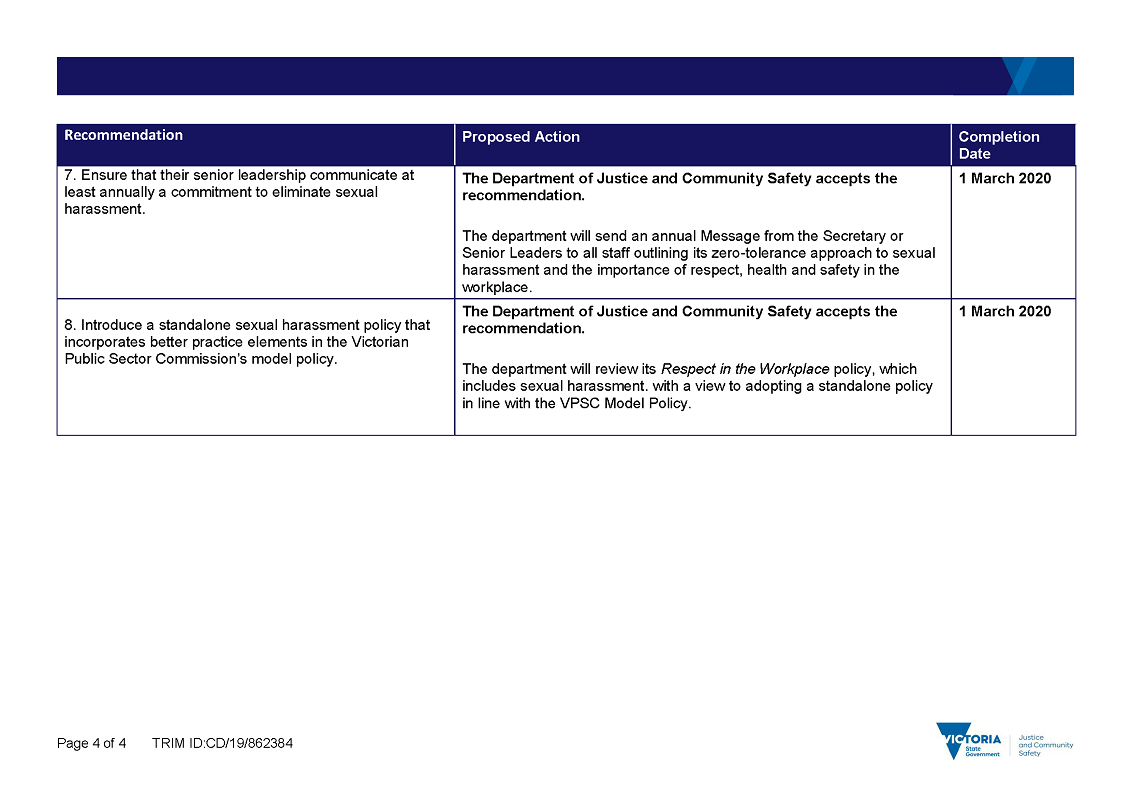

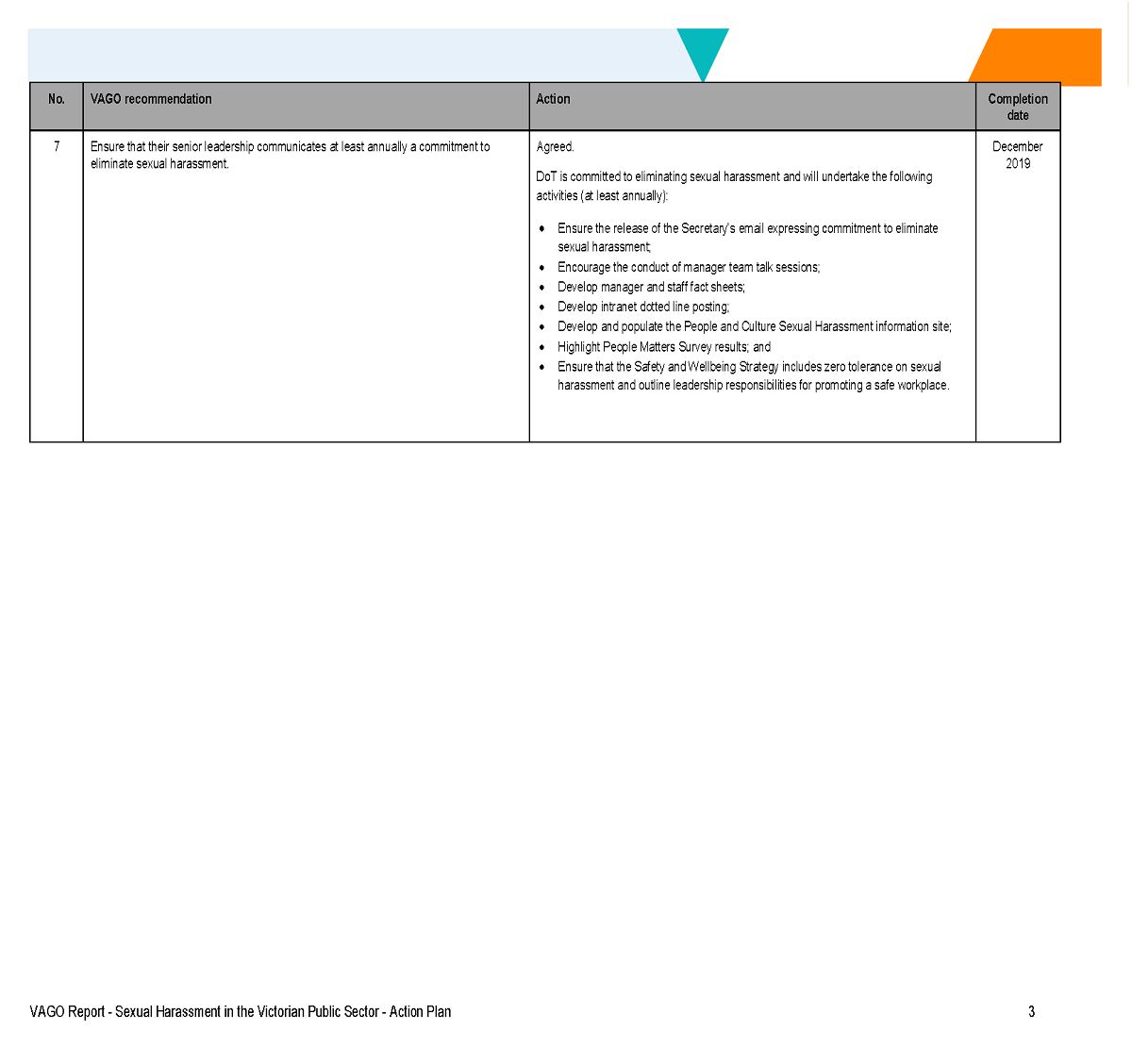

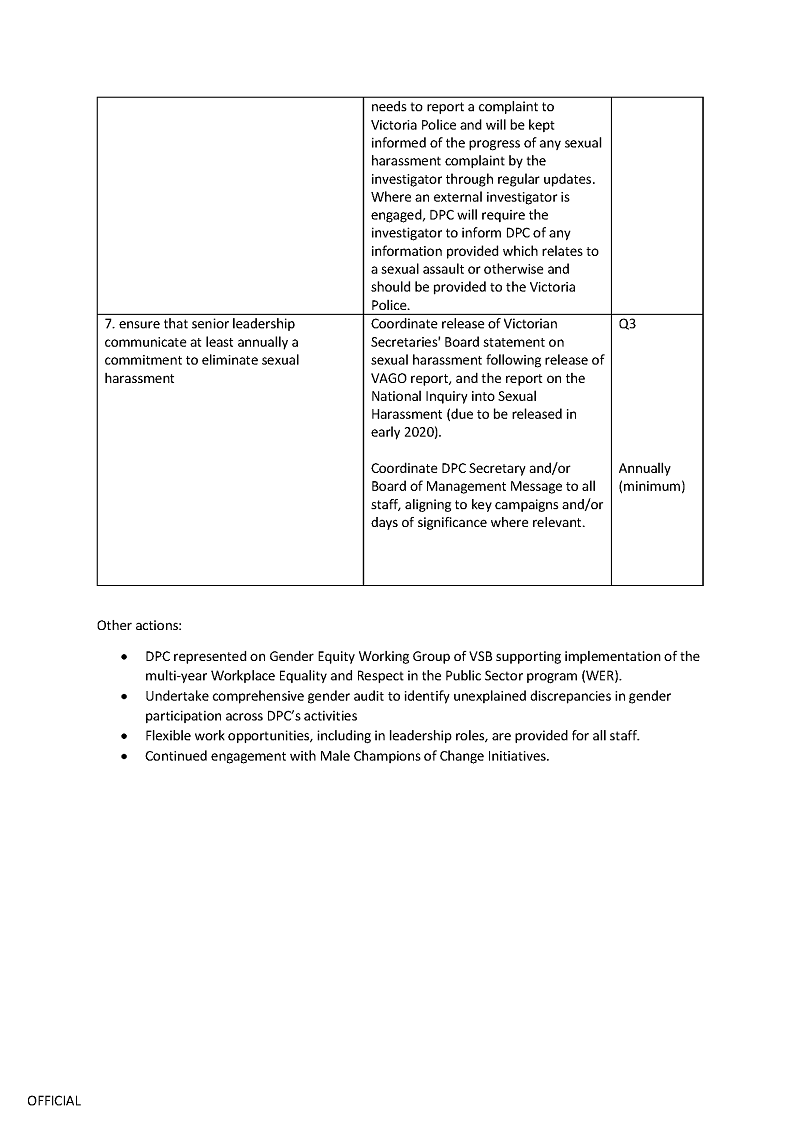

7. ensure that their senior leadership communicate at least annually a commitment to eliminate sexual harassment (see Section 4.5).

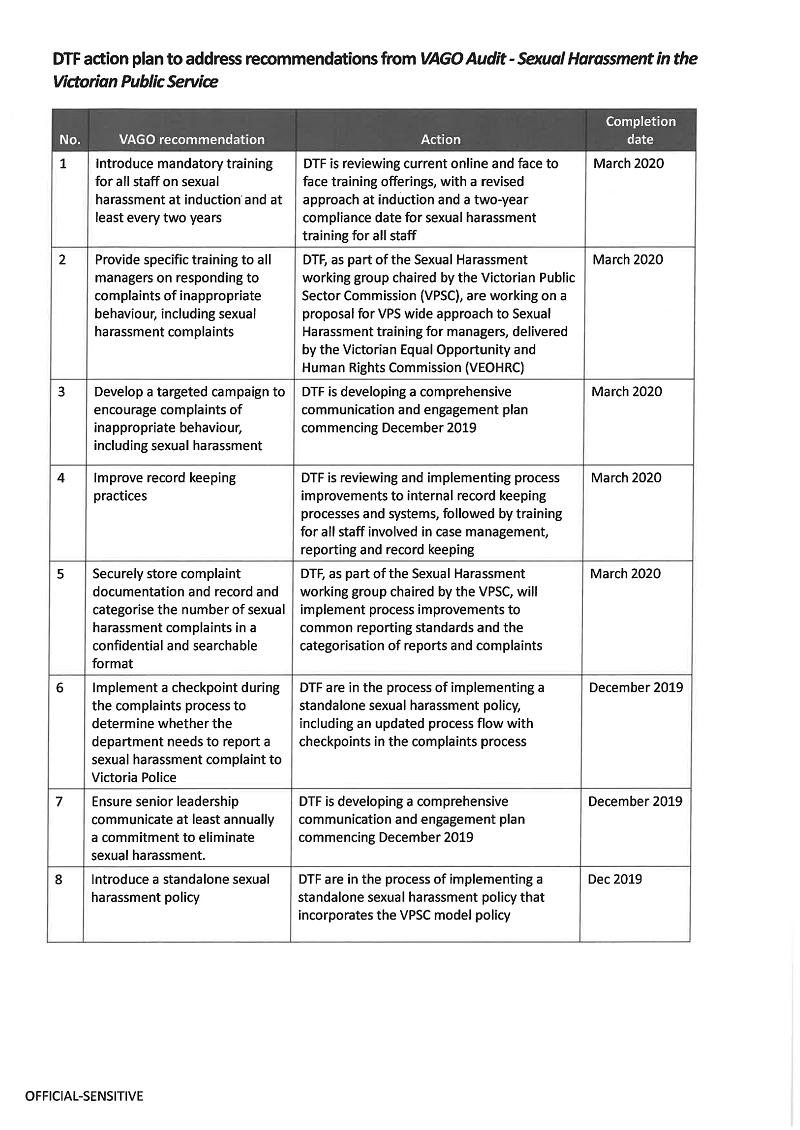

We recommend that the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Department of Treasury and Finance:

8. introduce a standalone sexual harassment policy that incorporates better practice elements in the Victorian Public Sector Commission's model policy (see Section 4.2).

We recommend that the Victorian Public Sector Commission:

9. develop guidance for departments on investigating matters with no independent witnesses (see Section 3.3)

10. review and expand guidance for departments on reporting matters to Victoria Police (see Section 3.3)

11. develop guidance to ensure that departments understand the level of information they can share with complainants and others when the investigation concludes (see Section 3.4).

We recommend that the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission:

12. develop guidelines on:

- how to address and respond to anonymous complaints

- what to do if a victim does not want to proceed

- what to do if a subject resigns before the conclusion of an investigation

- how to refer complainants to external bodies (see Part 3).

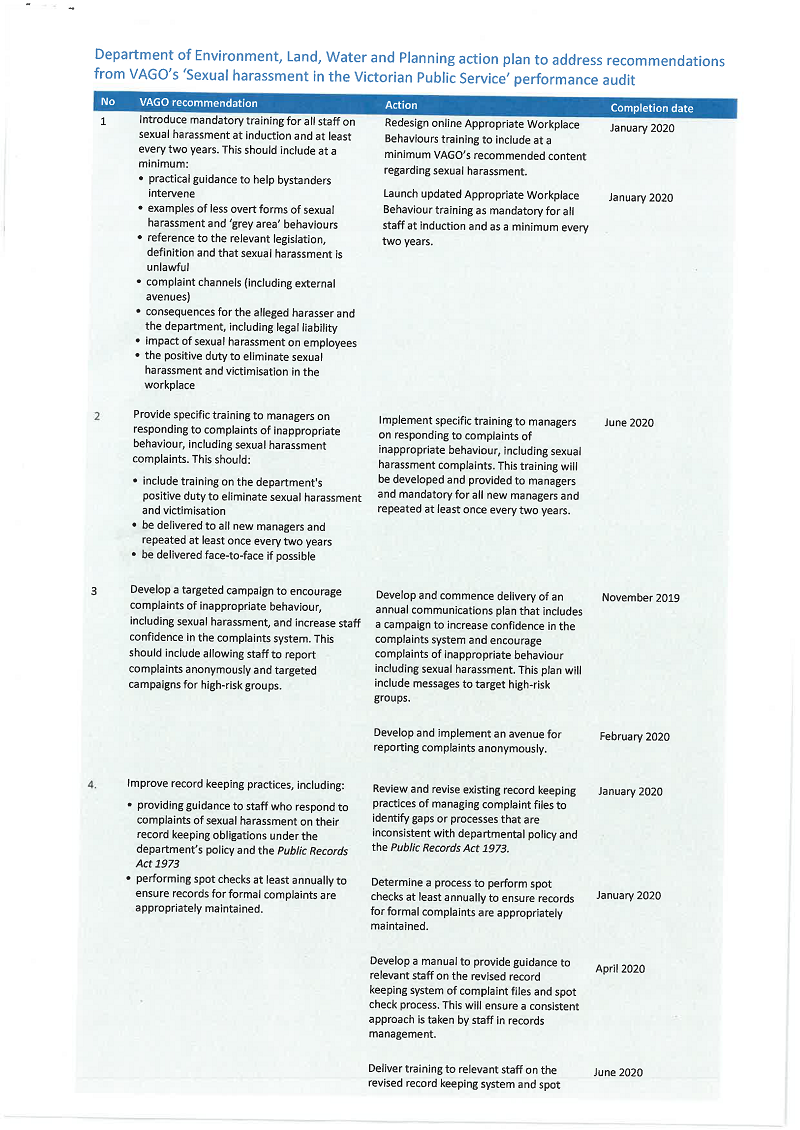

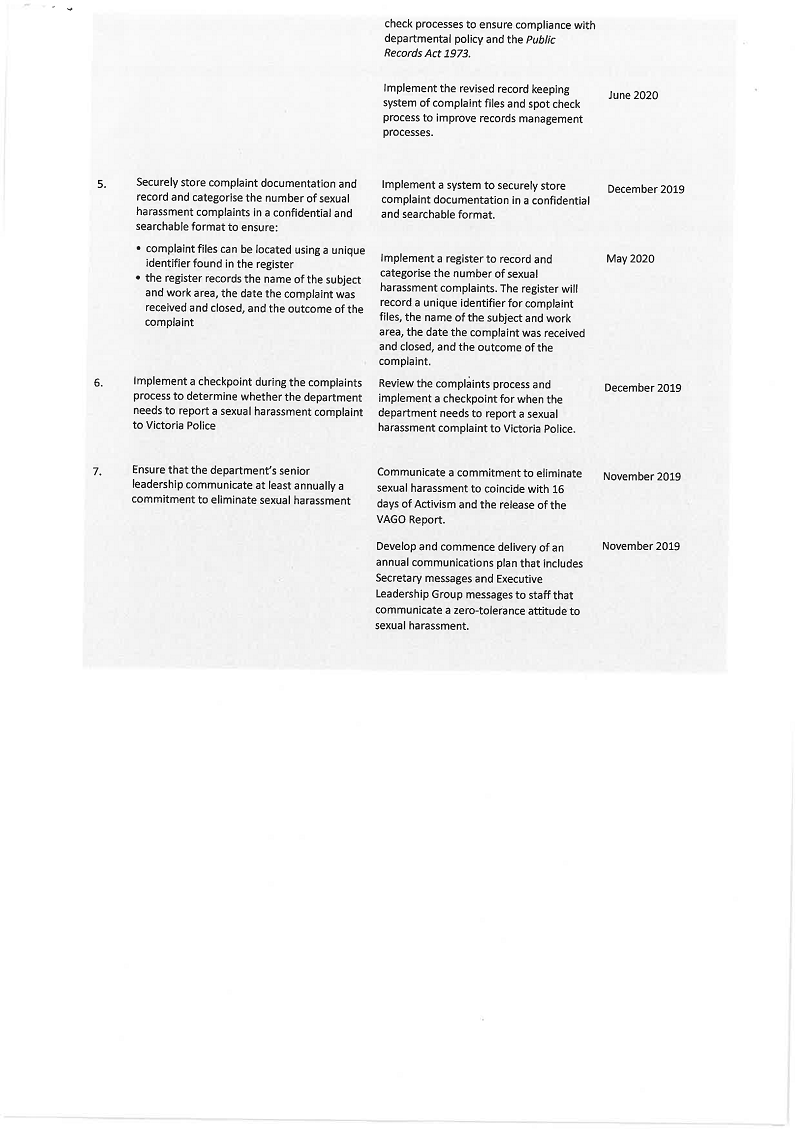

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DELWP, DET, DHHS, DJCS, DJPR, DoT, DPC, DTF, VEOHRC, VPSC and WorkSafe Victoria, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

The following is a summary of those responses. We include the full responses in Appendix A.

- All departments accept the recommendations directed to them and have produced action plans detailing how they will address them.

- VPSC and VEORHC accepted the recommendations directed to them.

- WorkSafe Victoria did not comment on the draft report as there were no recommendations or findings directed to it.

1 Audit context

Sexual harassment in the workplace is unlawful and can have significant negative effects on individuals and their employers. In some cases, sexual harassment is also a criminal offence.

A national survey by the AHRC in 2018 showed that sexual harassment is common. One in three people reported being sexually harassed at work in the past five years.

In the Victorian public service, this rate appears to be lower. In 2019, 7 per cent of departmental respondents to the VPSC's PMS said that they had experienced sexual harassment at work in the previous 12 months.

Under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, organisations including Victorian government departments must take reasonable and proportionate measures to eliminate sexual harassment in their workplaces. This audit examines the effectiveness of those steps.

1.1 Why this audit is important

There is growing awareness of the impact that sexual harassment in the workplace can have on individuals, employers and the wider organisation.

Impact on individuals

Academic research suggests that sexual harassment at work can cause significant physical, mental and financial harm to individuals. The AHRC's 2018 Everyone's business: Fourth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces reports that most sexual harassment victims experience some short or long‑term consequences. It has been linked to depression, anxiety and other health issues, absenteeism and reduced job satisfaction.

Impact on employers

Research also shows that sexual harassment is costly to employers. It can cause workplace disruption, impact employee productivity, damage culture and increase employee absenteeism and turnover.

Unless the relevant organisation has taken reasonable precautions to prevent sexual harassment, a tribunal may find it vicariously liable for the sexual harassment perpetrated by its employees. Even without the risk of litigation, it is costly to an organisation to investigate and act on complaints.

Why this audit is important now

Since 2016, PMS data has shown that sexual harassment is an issue for Victorian government service employees. At the same time, the AHRC's National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment, which began in 2018, and international movements such as the #MeToo campaign have renewed attention on the issue of sexual harassment.

In 2018, the Victorian government signalled its commitment to preventing and responding to sexual harassment. The Victorian Secretaries Board (VSB) issued a statement that 'any form of sexual harassment in any public sector workplace is unacceptable' and formed a working group, chaired by the VPSC. In November 2018, the VPSC introduced the model policy and Guide for the Prevention of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace (the guide).

It is timely for us to assess whether the departments are providing workplaces that are free from sexual harassment.

1.2 What is sexual harassment?

The Equal Opportunity Act 2010 defines sexual harassment in the workplace as any unwelcome behaviour of a sexual nature that makes a person feel offended, humiliated, and/or intimidated in circumstances where a reasonable person would expect that reaction.

Anyone can perpetrate or experience sexual harassment. The model policy and guide outline various forms of sexual harassment, including:

- comments or questions of a sexual nature about a person's private life or their appearance

- sexually suggestive comments or jokes

- displaying offensive screensavers, photos, calendars, or objects of a sexual nature

- sexually explicit emails, text messages or posts on social networking sites

- repeated requests to go out on dates

- requests for sex or sexual favours

- sexually suggestive behaviour, such as leering, staring or offensive gestures

- unwelcome physical contact of a sexual nature including brushing up against someone, touching, fondling, or hugging

- actions or comments of a sexual nature in a person's presence (even if not directed at that person)

- sexual assault, indecent exposure, physical assault, and stalking (which are also criminal offences).

Sexual harassment can occur even when the perpetrator does not intend it. It does not need to be a repeated behaviour.

Risk factors

Sexual harassment can occur in any workplace and to any person. Research shows that certain factors can increase the risk of sexual harassment, including:

- poor organisational culture

- unequal power between men and women

- rigid gender stereotypes

- predominately male workforces

- hierarchical power structures.

1.3 Prevalence and complaints

Departments can use PMS data to look at culture and the prevalence of sexual harassment within the organisation. However, as an anonymous survey, the PMS does not give detail on individual complaints. Departments need to encourage complaints so that they can act on inappropriate behaviour.

VPSC's model policy and the AHRC's Code of Practice for Employers 2008 recommend that employers have formal and informal channels for sexual harassment complaints. Figure 1A shows possible complaint channels, responses and outcomes.

Figure 1A

Possible complaints channels, responses and outcomes

Source: VAGO.

The department will determine how to handle the complaint, and should take into account the:

- nature of the complaint

- wishes of the complainant

- outcome the complainant is seeking

- initial channel for submitting the complaint

- need to protect employees.

1.4 Responding

When a department becomes aware of sexual harassment, it should act quickly and effectively and ensure it protects staff from victimisation. If a complaint is made, where appropriate, departments should encourage the relevant parties to resolve the complaint through informal procedures rather than through a formal investigation.

There may be instances where a formal complaint or response is necessary. If a disciplinary outcome is required, the department may initiate a formal misconduct process under Clause 21 of the Victorian Public Service Enterprise Agreement 2016 (the enterprise agreement).

These processes should be well documented, timely, and uphold procedural fairness. They should also include supports for all parties, as the response to a sexual harassment complaint can be distressing for all involved.

1.5 Prevention

Departments must take reasonable steps to eliminate sexual harassment in their workplaces.

Figure 1B shows the key steps for preventing sexual harassment.

Figure 1B

Sexual harassment prevention

Source: VAGO.

1.6 Legislation, policy and guidance

Sexual harassment in the workplace is unlawful and prohibited under Victoria's Equal Opportunity Act 2010and the Australian Sex Discrimination Act 1984. Departments have a positive obligation to eliminate sexual harassment in their workplace as far as possible. Departments, as employers, must also provide a safe workplace under Victoria's Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

The legislative framework does not prescribe the structures organisations need to have to prevent and respond to sexual harassment. This means organisations have the flexibility to design a system that suits their size, risk profile and resources.

Appendix B provides an overview of key legislative and guidance material relevant to public sector bodies when developing their sexual harassment policies and procedures.

1.7 Who we audited and why

We included 11 agencies in this audit:

- All eight Victorian government departments—DELWP, DET, DHHS, DJCS, DJPR, DoT, DPC and DTF

- VEOHRC

- VPSC

- WorkSafe Victoria.

Victorian government departments

The eight Victorian government departments employ more than 36 000 staff. Departments are often seen as the leaders in the public service and how they act and respond to sexual harassment sets an important example for the rest of the public sector.

On 1 January 2019, the Victorian government split the former Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) into two new departments, DoT and DJPR. We assessed both the former DEDJTR, as well as DoT and DJPR. DoT supplied data that predates the transition of the former VicRoads and the former Public Transport Victoria into DoT, which occurred on 1 July 2019.

VEOHRC

VEOHRC has responsibilities under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 and the Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001. VEOHRC:

- provides education resources, training packages, practice guidance and consultancy services regarding sexual harassment

- can conduct investigations into potential systemic and serious matters of sexual harassment, discrimination or victimisation

- can review an organisation's compliance with human rights on request and enter into action plans with organisations to improve compliance with sexual harassment protections

- delivers a dispute resolution service for complaints about discrimination, sexual harassment, victimisation and racial or religious vilification.

VEOHRC can accept complaints from any person in Victoria, including government employees concerned about discrimination or harassment in their workplace.

VPSC

The role of the VPSC is to strengthen the effectiveness, efficiency and capability of the public sector. It issues codes of conduct and standards, monitors and reports on public sector compliance with these standards, and runs the annual PMS.

The VPSC:

- Deputy Commissioner chairs a VSB working group established to lead work on preventing and responding to sexual harassment in the workplace since March 2018

- released the model policy and guide in November 2018

- introduced the Respectful Workplaces Framework and the Prevention of Sexual Harassment – Model Action Plan in July 2019.

Together, these actions seek to support the public sector in preventing sexual harassment though improved policies and processes and by changing cultural norms.

WorkSafe Victoria

WorkSafe Victoria enforces occupational health and safety and accident compensation laws in Victoria. It aims to prevent workplace injury, disease and death. Staff who are injured at work, including those who experience mental health issues because of harassment, can make a workers' compensation claim. WorkSafe Victoria (or its agents) receives, assesses and determines claims for compensation. It also educates employers to achieve healthy and safe working environments.

1.8 What this audit examined and how

This audit examined whether the Victorian public service provides workplaces that are free from sexual harassment.

We assessed whether departments:

- have effective measures to prevent and report on sexual harassment

- respond to complaints of sexual harassment in a fair and effective manner.

Methods used

As part of the audit we:

- analysed raw data from the PMS undertaken from 2016 to 2019 for the audited departments and the former DEDJTR

- ran an online public submissions process. We received 27 submissions—two from organisations and 25 from departmental staff—on their experiences and views of sexual harassment in the Victorian public service

- examined departmental documentation, including policies, training, action plans and prevention strategies

- reviewed a selection of sexual harassment complaint files in each department.

We also conducted our own survey for departmental staff on sexual harassment. Our survey did not include staff working in prisons or statutory authorities.

Our survey asked about:

- individual experiences of sexual harassment and impact

- why respondents did or did not complain

- the adequacy of policies

- the effectiveness of training

- views on departmental communication and prevention.

The PMS asks staff about their experiences of sexual harassment and why they did not complain or whether they were satisfied with how the department handled their complaint. Our survey asked additional questions to gain further insight on sexual harassment.

Our survey was open for two weeks and received 4 811 responses. We received too few responses from DJPR and DOT to use in our analysis. We removed these responses from our analysis, which brought our response total to 4 729. The response rates for each remaining department ranged between 10 and 26 per cent.

We refer to both the PMS and our own survey throughout the report. While survey data is the best data source we have for understanding prevalence of sexual harassment, it is limited by response rates. It may not capture all staff who experience sexual harassment.

We conducted this audit in accordance with the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $520 000.

Any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

1.9 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the prevalence of sexual harassment and whether department workplaces are free from harm.

- Part 3 examines how departments address complaints of sexual harassment.

- Part 4 examines what departments have done to prevent sexual harassment in their workplaces.

2 Prevalence of sexual harassment

To address sexual harassment in their workplaces, departments must first understand its prevalence. They can then:

- identify trends and key demographics

- identify high-risk groups in their workforce

- determine whether prevention initiatives are working.

Departments rely on those who experience or witness sexual harassment to report these matters. This enables departments to measure the prevalence of sexual harassment in their organisation. Staff can report sexual harassment by making a complaint to their department or by taking part in surveys.

We assessed complaints and survey data to measure the prevalence of sexual harassment in the departments. We also assessed whether departments understand the prevalence of sexual harassment in their organisations and can identify and act on high-risk areas in their workforce.

2.1 Conclusion

Sexual harassment occurs in every department. Approximately one in 14 respondents reported experiencing sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to the 2019 PMS. The 2019 PMS also shows that certain groups of people are at increased risk of sexual harassment, such as those with a self-described gender identity or LGBTIQ individuals and young women.

Since 2016, the PMS has reported a reduction in the percentage of departmental respondents experiencing sexual harassment. While positive, more data is needed to feel confident that this is a sustained trend.

While the PMS provides data on high-risk demographics and poorly performing business units, it shows that formal complaints are significantly underreported. The underreporting, coupled with inadequate systems to capture informal complaints, means that the ability of departments to understand sexual harassment prevalence and proactively identify and act on sexual harassment is limited.

2.2 How common is sexual harassment?

One way that departments can measure the prevalence of sexual harassment is through survey data. The most comprehensive survey in Victoria is the annual PMS, due to its high response rates. The PMS has included questions on sexual harassment since 2016.

Prevalence in the public service

|

The VPSC runs the PMS across Victorian public sector agencies. Within the seven departments, 19 821 employees responded to the 2019 survey. This reflects a response rate of 56 per cent. |

In Victoria, 7 per cent of departmental respondents to the 2019 PMS—or one in 14 respondents—reported experiencing sexual harassment in the past 12 months. This is down from 11 per cent of respondents in 2016, which is a statistically significant decrease. However, it is too soon to determine if sexual harassment is decreasing in Victorian departments in a sustained manner, as only four years of data is available. This is illustrated in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Departmental respondents who have experienced sexual harassment

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2016–19.

Factors that could influence this decrease include communication and initiatives to address sexual harassment that departments have implemented over the past four years. We discuss these measures further in Part 4.

Prevalence in other states

The VPSC was one of the first government agencies in Australia to include questions on sexual harassment in its survey of government staff. Four states—including Victoria—report publicly on rates of sexual harassment in their public service. The Australian Public Service (APS) also reports its results. The results are shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Sexual harassment prevalence across public services

|

State |

Respondents who experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to the relevant survey |

|---|---|

|

Queensland |

1% of respondents —Working for Queensland survey 2018 |

|

South Australia |

3% of respondents —I work for SA – Your Voice Survey 2018 |

|

Tasmania |

2% of respondents —State Service Employee Survey 2018 |

|

APS |

3.3% of respondents —APS Employee census 2018. |

|

Victoria |

9.4% of respondents —PMS 2018 |

Note: Response rates—Queensland (44%), South Australia (22%), Tasmania (30%), APS (74%), Victoria (56%).

Source: VAGO.

Differing survey design across the states may explain Victoria's higher results. In Victoria, the survey asks whether respondents have experienced certain types of behaviours—such as inappropriate touching, sexually suggestive comments, or sexually explicit messages. In contrast, other states' surveys do not ask about certain behaviours, but instead ask whether a respondent has experienced sexual harassment. As highlighted by the AHRC in its national survey, respondents may be more likely to say that they have experienced different types of behaviours than say they have experienced sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment experiences

Responses to our survey and public submission process show that individual experiences of sexual harassment can vary greatly:

- I have witnessed a manager saying that the only good place for a female is in a porn movie.

- … one of them manipulated caseloads to allow himself to be near a young married woman who he fancied.

- … when talking about work to be done she would suggestively comment about how I was on her 'to do list'.

- When greeting me, he would often touch my waist and one time he tickled me while I was seated.

- He pressed his penis against me when I was bending over to pick something up, and he asked me 'is that your preferred position'.

- I was repeatedly asked out on a date by a colleague who also contacted me at home and spoke to my children.

- He then began to send me SMSs after hours, including the middle of the night, of a sexual nature.

The 2019 PMS found that the types of sexual harassment most commonly experienced by respondents were intrusive comments and questions of a sexual nature, as shown in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

Types of sexual harassment experienced by departmental respondents

Note: n=1 465. Respondents could select more than one type.

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

In our survey, we found that there are some forms of sexual harassment that respondents perceived as 'less serious' than other types. However, these behaviours must be addressed, as the negative impact on those who experience them can be high. A meta-analysis conducted by Sojo, Wood and Genat from the University of Melbourne (2015) found that frequent experiences of sexual harassment that some people may term as 'less serious' had similar negative impacts on a person's wellbeing to a 'more serious' experience. All forms of sexual harassment are serious, and departments should address them.

Prevalence within departments

The VPSC provides departments with detailed reports on their PMS results. The reports show the rates of sexual harassment by group, division, branch, team, or unit, where the number of respondents is greater than 10.

Participation in the PMS is voluntary. DoT did not participate in the 2019 PMS, due to the timing of machinery of government changes resulting in large-scale organisational change. As such, we have no data to confirm the prevalence of sexual harassment in this department.

Figure 2D shows the percentage of respondents in each department who reported that they had experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to the 2019 PMS. As departments had different survey response rates, we have presented results within a margin of error. The results reveal that:

- the difference in rates of sexual harassment reported by respondents at DPC, DET and DELWP are not statistically significant

- DJCS respondents experienced the highest rates of sexual harassment compared to other departments. This is statistically significant. DJCS staff who work in prisons or with past offenders experience higher rates of sexual harassment, so we have separated these respondents.

Figure 2D

Respondents in each department who experienced sexual harassment

Note: Results presented within a margin of error due to varied response rates. The line represents the upper and lower bound of results with a 95% confidence interval.

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

2.3 Employees at high risk

Any employee can experience sexual harassment. However, the 2019 PMS shows that certain groups of respondents are at higher risk, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Groups at higher risk

|

Attribute |

Experienced sexual harassment (%) |

Compared to |

|---|---|---|

|

Self-described gender identity(a) |

26 |

6 per cent of respondents who identified as men and 8 per cent of respondents who identified as women |

|

LGBTIQ sexual orientation |

13 |

7 per cent of opposite-sex attracted respondents |

|

24 years of age or under (all genders) |

12 |

5 per cent of respondents aged 45 years or above. |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

12 |

7 per cent of non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondents |

|

Earning less than $75,000 |

11 |

3 per cent of respondents earning above $155,000 |

(a) A low number of respondents had a self-described gender identity (n=80). Because of this low number, there may be uncertainty around the 26%. The 95% confidence interval for the rate is 17 to 37%

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS 2019 data.

Departments can use this information to better target strategies and communication so that they can give the right level of support to everyone. We discuss this further in Part 4.

Gender, age and income

Individuals with a self-described gender identity and young women are at higher risk of experiencing sexual harassment. The PMS data shows that in all age categories, those with a self-described gender identity experienced the highest rates of sexual harassment, followed by women aged 15 to 24.

Figure 2F shows the rates of sexual harassment experienced by men and women in different age brackets.

Figure 2F

Respondents who experienced sexual harassment

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

We also found that respondents who earned less experienced sexual harassment at a higher rate, as shown in Figure 2G.

Figure 2G

Respondents in each salary bracket who experienced sexual harassment

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

2.4 Impact and response

People who experience sexual harassment respond in different ways. Many find that their mental and physical health suffers, as do their personal relationships and careers.

Sexual harassment also affects organisations.

Impact on individuals

Sexual harassment can have a significant impact on an employee's mental and physical health. Through our survey and submission process, respondents shared their experiences and described how sexual harassment impacted their lives.

In our survey, 12 per cent of respondents who experienced sexual harassment said they were negatively impacted. These respondents reported the ways that sexual harassment negatively impacted their overall wellbeing.

|

Reported negative impact |

Result (%) |

|

Mental health and caused me stress |

68 |

|

Self-esteem and confidence |

53 |

|

Relationship with partner, children, friends, or family |

14 |

|

Employment, career, or work |

46 |

|

Financial situation |

4 |

Note: n=167. Respondents could select more than one answer. Results are shown as a percentage of respondents who said they experienced sexual harassment and were negatively impacted.

Source: VAGO survey 2019.

|

|

Impact on organisation

At an organisational level, the consequences of sexual harassment can include reduced workforce morale, increased absenteeism, turnover and potential litigation, or reputational costs. From respondents of the 2019 PMS who experienced sexual harassment:

|

Response to harassment |

Result (%) |

|

Took time off work |

7 |

|

Sought a transfer to another role/location/roster |

3 |

Note: n=1 465. Respondents could select more than one option. Results are shown as a per cent of respondents who said they experienced sexual harassment and were negatively impacted.

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

Response

Where someone said that they had experienced sexual harassment, the 2019 PMS asked how they responded. The top five responses were:

|

Response |

Result (%) |

|

|

1 |

Pretended it didn't bother you |

50 |

|

2 |

Tried to laugh it off or forget about it |

38 |

|

3 |

Avoided the person(s) by staying away from them |

37 |

|

4 |

Told a colleague |

26 |

|

5 |

Told the person the behaviour was not ok |

25 |

Note: n=1 465. Respondents could select more than one option. Results are shown as a percentage of respondents who said they experienced sexual harassment.

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

In the 2019 PMS, of those who said they experienced sexual harassment, 3 per cent also said that they submitted a formal complaint, 2 per cent said they told HR, and 17 per cent told their manager.

Complaints

The number of sexual harassment complaints reported to HR is comparatively low. Figure 2H compares the number of complaints recorded by the departments between July 2016 and March 2019 and the number of respondents who said in the 2019 PMS that they experienced sexual harassment. DJCS and DHHS could not quantify the number of sexual harassment complaints they received, which we discuss further in Section 3.2.

Figure 2H

Formal complaints recorded by departments compared to PMS results

|

Department |

Employees (2019) |

Experienced sexual harassment over 12-month period (2019 PMS)(a) |

Formal sexual harassment complaints recorded over the past three years (July 2016 to March 2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

DET |

5 151 |

212 |

4 |

|

DELWP |

3 950 |

154 |

3 |

|

DJPR |

2 787 |

143 |

Former DEDJTR 2 DJPR 1 |

|

DoT |

650 |

Not undertaken (b) |

DoT 0 |

|

DHHS |

11 545 |

357 |

Cannot quantify |

|

DJCS |

10 177 |

539 |

Cannot quantify |

|

DPC |

1 099 |

42 |

4 |

|

DTF |

729 |

18 |

4 |

(a) These numbers reflect responses to the 2019 PMS. There could be more staff who experienced sexual harassment that did not take part in the PMS.

(b) DoT did not participate in the PMS survey due to the timing of the machinery of government changes resulting in a large organisational change.

Source: VAGO analysis of departmental records and PMS data 2019.

We discuss complaint management and potential reasons for underreporting in more detail in Part 3.

3 Sexual harassment complaints

When staff make a sexual harassment complaint, departments should respond quickly and effectively. To do this, all departments need a response framework that:

- has multiple avenues for employees to lodge a complaint

- enables them to respond to complaints quickly, sensitively and proportionately

- ensures that they take action when they substantiate sexual harassment

- supports all employees involved in the process.

If a department can do these things, it increases the faith of their staff in the system. This may lead to greater reporting of sexual harassment by employees.

We assessed whether departments have systems that encourage complaints and respond in a fair and effective manner. We also considered whether staff have faith in the complaints process.

3.1 Conclusion

Departments have adequate processes to receive and respond to complaints in a fair and effective manner. This includes different types of complaint channels, however staff often do not use them.

How departments handle complaints is crucial to increasing staff confidence. We found delays, poor investigative practices, a lack of transparency and inaccurate and incomplete records of how departments manage complaints. This puts departments at risk if their decisions are challenged and weakens staff trust in the system.

Our survey found that underreporting is due to many factors, including employee perceptions that their complaint is not serious enough, fear that there will be negative consequences, or lack of faith in the system. To address underreporting of sexual harassment, departments need to do more to increase staff confidence in the complaints system.

3.2 Encouraging complaints

Departments need to encourage employees to make complaints when sexual harassment occurs. We assessed the complaint management frameworks at departments, including:

- complaint channels available to employees

- how departments record and store complaints

- complaint rates

- reasons why employees do not complain.

Complaint channels

Complaint channels vary across departments. All department policies outline at least two ways for employees to complain (either to their manager or HR). Some departments provide further channels for employees to seek advice, as outlined below.

|

Complaints channel |

Availability |

|

Formal complaint to HR |

All departments |

|

Speak with manager |

All departments |

|

Peer support officers (staff in the department who can give confidential advice on options and supports available. They do not take complaints.) |

DET, DELWP, DHHS and DTF |

|

Online system for reporting occupational health and safety matters, including sexual harassment |

DELWP, DHHS and DJCS |

|

Workplace conciliators (provide confidential, impartial and informal support on workplace issues and complaint avenues. They can also facilitate difficult conversations or coach staff.) |

DELWP, DHHS, DJPR and DoT |

Complaint channels only work if employees know about them. Our survey found that only 49 per cent of respondents knew how to make a formal complaint about sexual harassment to their department.

Employees can also make a complaint to an agency outside of their department, such as:

- VEOHRC and AHRC

- WorkSafe Victoria

- Victoria Police (if a criminal matter)

- Fair Work Commission

- Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

When we commenced this audit all departments (except DTF and DPC) listed AHRC/VEOHRC, WorkSafe Victoria and Victoria Police as external avenues in their policies. DPC has since updated its policy to detail all external avenues for reporting complaints about sexual harassment.

Staff do not have a strong understanding of these reporting avenues. Our survey found that 50 per cent of respondents know how to report their complaint to external bodies.

Anonymous complaint channels

Various Ombudsman complaint handling guides state that it is good practice to accept anonymous complaints. Research into sexual harassment and assault in Australian universities supports this view. The 2017 On Safe Ground report from the University of New South Wales highlights that centralised and anonymous complaint channels enable systematic recording of incidents and can encourage staff to report sexual harassment.

Departmental staff have limited avenues to lodge concerns anonymously or online to their department. No department has a dedicated anonymous hotline or online channel for sexual harassment matters.

Further, the VPSC's model policy and departmental policies do not encourage anonymous complaint channels. Some departments stated that anonymous complaints make it difficult for them to ensure that:

- the complainant has access to support services

- the alleged harasser receives procedural fairness

- they investigate matters, as there may be insufficient information on specific allegations.

However, departments can use anonymous complaints to obtain useful insight into their organisations and address cultural and behavioural issues in the relevant group. This can include:

- prompting an appropriate workplace behaviour campaign or targeted training (focusing on the area the complaint is from)

- capturing complaints against the same subject, which may lead the department to instigate its own investigation

- prompting pulse surveys or staff feedback within the relevant area to test issues raised.

Capturing complaints

All departments record formal complaints about sexual harassment, but the level of information captured varies across departments. Complaint registers range from online case management systems to Excel spreadsheets.

Shortcomings of departmental registers include:

- having multiple registers run by different people who capture different levels of information across regions or groups

- their inability to run a report on different variables, such as open investigations

- incorrectly categorising a sexual harassment complaint as a bullying or discrimination complaint

- inability to report on the number of sexual harassment complaints across the department.

How many employees make a complaint?

Significant underreporting of sexual harassment occurs across all departments. While the rate of sexual harassment reported in the PMS has decreased from 11 per cent in 2016 to 7 per cent in 2019, of those that experience sexual harassment, few complain. The 2019 PMS shows that only 3 per cent of those who experienced sexual harassment made a formal complaint, down from 5 per cent in 2018.

Figure 3A

Respondents who experienced sexual harassment and made a complaint

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

Complaint rates across departments vary. Departments want their complaint rates to be high relative to those who experience sexual harassment. Figure 3B shows that DHHS and DJCS have the highest complaint rates from the 2019 PMS. However, the rates across all departments are low.

Figure 3B

Respondents who experienced sexual harassment and made a formal complaint or told a manager

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS 2019 data.

At DTF and DPC, no respondents said that they made a formal complaint about the sexual harassment they experienced. The orange line shows that a higher percentage of respondents chose to tell a manager about the sexual harassment they experienced, although these figures are still low.

Reasons for not making a complaint

There may be many reasons why employees do not speak up about the harassment they experience. Reporting an incident of sexual harassment can be confronting and difficult. We found instances of respondents who feared that it would affect their safety and reputation or would not result in any action.

Our survey asked respondents who experienced sexual harassment why they did not make a complaint. The top five reasons were:

|

Reason |

Result (%) |

|

|

1 |

I didn't think it was serious enough |

50 |

|

2 |

I believed that there would be negative consequences for my reputation and/or career |

35 |

|

3 |

I didn't think it would make a difference |

32 |

|

4 |

I didn't believe that the complaint would result in any action |

29 |

|

5 |

I thought that the complaint process would be embarrassing or difficult |

20 |

Note: n=649. Respondents could select more than one answer. Results shown as a percentage of respondents who experienced sexual harassment and did not make a formal complaint.

Source: VAGO survey 2019.

Only 7 per cent said they did not make a complaint because they did not know how. We explore the top three reasons for why respondents did not make a complaint below.

Perception of seriousness of complaint

Based on our survey, the most common reason for not reporting sexual harassment was the respondent's belief that it was not serious enough. We heard from survey respondents who felt that their department's processes were not well equipped to deal with sexual harassment that was 'low level' or a 'minor' incident.

These responses highlight the need for departments to:

- have response frameworks that include options for informal responses to sexual harassment (discussed in Section 3.3)

- train staff on what sexual harassment is, including that 'grey area' behaviours can still be sexual harassment and are inappropriate (discussed in Section 4.3)

- encourage and train bystanders to speak up when they witness sexual harassment, even if they feel it is a 'minor' or 'low level' incident (discussed in Section 4.3).

- train managers on their obligation to address sexual harassment and deal with this at a local level (if appropriate) or escalate to a formal process (discussed in Section 4.4).

Fear of negative consequences

In our survey, 35 per cent of those who experienced sexual harassment and did not make a formal complaint said it was because they believed there would be negative consequences if they did.

Lack of faith

Perceptions and other people's experiences can affect staff confidence in the complaints process. Of those who said in the 2019 PMS that they had experienced sexual harassment, only 26 per cent agreed with the statement, 'I am confident that if I raised a grievance in my organisation, it would be investigated in a thorough and objective manner'. In our survey, we heard from respondents who did not have faith in the system.

The way that a department responds to all complaints will impact faith in the system. We discuss this further in Section 3.4.

3.3 Responding to complaints

When an employee lodges a sexual harassment complaint, a department should act quickly and effectively. Sexual harassment complaints can be sensitive and complex and can involve significant distress for the parties involved.

Both the VPSC's model policy and the AHRC's Code of Practice encourage employers to have both formal and informal responses to sexual harassment complaints. All departments include both options in their policies.

Informal responses

Department policies encourage an informal response where possible. According to VEOHRC, informal responses are 'forward looking', meaning they focus on resolving the matter and support a working relationship, rather than proving harassment occurred and taking disciplinary action.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Generally resolved quickly within the team or workgroup Less intimidating for all parties, as the process is less rigid Encourages open communication |

The department often holds limited documentation and does not record the matter centrally Formal disciplinary action is not taken, so repeat offenders may not be tracked or identified |

Data from the 2019 PMS shows that many respondents preferred an informal response. This included speaking to their manager or a colleague, rather than speaking to HR and submitting a formal complaint.

|

Response to harassment |

% of those who experienced sexual harassment |

|

|

Informal |

Told a colleague |

26 |

|

Told a manager |

17 |

|

|

Formal |

Submitted a formal complaint |

3 |

|

Told HR |

2 |

|

Note: n=1 465. Respondents could select more than one answer. Results shown as a percentage of respondents who experienced sexual harassment.

Source: VAGO analysis of PMS data 2019.

VEOHRC warns that informal processes often become 'hidden' in an organisation. The direct line manager usually handles informal complaints, and HR does not know their volume and nature. As a result, we could not determine the number of informal complaints and how departments dealt with them.

Formal responses

An informal response is not always appropriate. Where a sexual harassment complaint may require formal disciplinary action, the department needs to take a formal response. This often involves investigating the allegations.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Necessary for where the department decides the actions may contravene its code of conduct or a provision of the Public Administration Act 2004 Has a more robust process involving an assessment of the evidence and, if necessary, investigation of the complaint Department keeps records that it may refer to in the future |

Requires more from the complainant, such as submitting written complaints or attending interviews Can be lengthy Can be difficult for all parties |

Deciding how to respond

When a department receives a formal complaint of sexual harassment, it needs to decide how to respond. Under the enterprise agreement, when an employee alleges misconduct, a department may:

- conduct an initial assessment to determine if an investigation is required

- determine that it is appropriate to begin an investigation immediately.

According to VPSC guidance, the initial assessment should be simple and involve basic fact-finding to determine whether a formal investigation is appropriate.

VPSC recommends that the department clearly document the outcome of the initial assessment. This is especially important in cases where the department determines that an investigation is not warranted.

We assessed a selection of 21 formal sexual harassment complaints across the departments and how they responded. As illustrated by Figure 3C, departments can take different approaches to resolving formal complaints. We found two cases where departments had not adequately documented the reasons why a complaint was not investigated.

Figure 3C

Responses to the formal complaints we reviewed

Source: VAGO analysis.

Investigations

Of the 21 complaint files we reviewed, 15 proceeded to an investigation. Of these:

- seven cases were substantiated

- five cases were not substantiated

- three cases were stood down due to the subject resigning.

In examining these cases, we saw instances of poor handling, such as:

|

Issues |

Findings |

|

Procedural fairness |

|

|

Timeliness |

|

|

Inconsistency |

|

We also found issues with:

- incomplete documentation and poor record keeping

- poor application of the Briginshaw principle (discussed below)

- inconsistent responses to criminal matters

- investigations not occurring when there were no independent witnesses

- failure to finalise investigations when the subject resigns before the department concludes its investigation.

Incomplete documentation and poor record keeping

To comply with the Public Records Act 1973, departments must keep full and accurate records. These records must allow others to easily understand what decisions the department made and why.

Ten of the 21 complaints we reviewed had missing or incomplete documentation. This ranged from minor instances, such as missing file notes of telephone conversations, to more serious lapses such as:

- failure to record the rationale for key decisions

- final investigation reports not on file.

These instances may breach the Public Records Act 1973 and expose the department to risk. A department may also not be able to defend its decisions if an outcome is appealed or a complainant initiates legal action.

Poor application of the Briginshaw principle

When investigating sexual harassment in the workplace, the investigator must form a view of the allegations on the balance of probabilities. This means that the investigator, in considering all available evidence, must determine whether it is more probable than not that sexual harassment occurred.

However, the High Court's decision in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336, known as the Briginshaw principle, means that while findings are made on the balance of probabilities, more serious allegations must be supported by stronger evidence.

We saw one case where a department misinterpreted the Briginshaw principle when substantiating an allegation. The investigation report weighed up the evidence and determined that the alleged conduct 'likely occurred', which is the required standard of proof. This should have meant that the allegation was substantiated. However, the report went on to say that the allegation could not be substantiated, due to heightened evidentiary standards required for more serious allegations.

The Briginshaw principle does not change the standard of proof based on the seriousness of the allegation.

While it is appropriate for departments to require stronger evidence when considering serious allegations, they must still determine whether it is more likely than not that the alleged conduct occurred. Such misinterpretations may lead to allegations not being substantiated, even though investigators are satisfied that the allegation was more likely than not to have occurred.

Responding to criminal matters

Some forms of sexual harassment are also criminal offences, such as stalking, sexual assault and indecent exposure.

Three of the 21 complaints we reviewed included alleged criminal conduct. All cases were dealt with differently:

- One department consulted with Victoria Police before starting the investigation, which we consider to be good practice and consistent with the model policy.

- One department did not refer the matter to Victoria Police because they believed that they should only refer substantiated matters.

- One department did not refer the matter to Victoria Police as the complainant expressed their wish not to do so on multiple occasions.

This is a difficult decision for departments, as they should balance the wishes of the complainant and the need to respond quickly with a requirement to report to Victoria Police. The following guidance is available for departments:

|

Source |

Guidance |

|

Independent Anti‑corruption Broad‑based Commission guide on conducting internal investigations (2016) |

'Never make a finding in a report that a person has committed or is guilty of any criminal offence. It may be appropriate, however, to make a finding that there is sufficient evidence to warrant referring the matter to Victoria Police, IBAC or another appropriate agency.' |

|

VPSC model policy (2018) |

'If an allegation appears to be a matter relevant to the police, the [department] is obliged to report this to the police regardless of whether the complainant has made a report to the police or not.' |

|

VPSC Management of Misconduct Policy (2019) |

'Matters of potential employee criminal conduct must be promptly reported to appropriate external agencies/authorities.' This policy only applies to Victorian Public Service employees covered by the enterprise agreement. |

|

AHRC Code of Practice (2008) |

'If an employer suspects that a criminal incident has occurred, the individual should be advised to report the matter to the police as soon as possible and be provided with any necessary support and assistance.' |

Departments must ensure that their actions will not prejudice any current or future criminal investigations, but also protect staff from further harm.

Departments should also document the rationale for not referring sexual harassment allegations to Victoria Police.

No independent witnesses

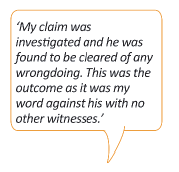

No independent witnesses

We found cases where the department did not investigate allegations or did not substantiate a complaint because there were no independent witnesses.

By its nature, sexual harassment may often occur where there are no independent witnesses. A department's decision to not conduct or substantiate an investigation should not solely be on the basis that there was no independent witness. This wrongly suggests that people should only report sexual harassment if others witnessed it.

The AHRC Effectively preventing and responding to sexual harassment: Code of Practice for Employers (2008) states that when there is no independent witness, departments should consider:

- evidence that the complainant discussed their concerns with a third party

- supervisors' reports and personnel records (for example, unexplained requests for transfer or shift changes, sudden increase in sick leave)

- complaints or information provided by other employees about the behaviour of the alleged harasser

- records kept by the complainant

- whether the parties presented their evidence in a credible and consistent manner

- the absence of evidence where it should logically exist.

We found two cases where the investigator did not consider such evidence or assess the credibility of witnesses.

Subject resigning before the end of an investigation

In some of the cases we reviewed, the alleged harasser resigned before the conclusion of the investigation.

In some cases, the department chose to continue the investigation. In others, the department discontinued the investigation and did not make a finding as to whether the sexual harassment occurred.

Departments have no requirements or guidance on how to make this decision. There may be practical reasons why a department chooses to discontinue an investigation at this stage. This includes resources, evidentiary issues, and their inability to compel a subject to participate in the process after they resign. However, there are also risks, including that:

- other employees may feel that the subject was not held accountable for their actions

- the subject may find work in another department as the complaint against them was not substantiated, and a disciplinary outcome was not imposed.

Through our survey and submission process, we heard from multiple employees who were concerned about subjects who resigned before their conduct could be investigated, and that alleged offenders have moved on to work at other departments.

On 1 October 2019, the VPSC extended the Victorian Public Service Pre‑employment Screening Policy, which previously only covered executives, to cover all staff in Victorian public service bodies. The policy requires candidates to self-report any misconduct investigation, even if it was not completed. This aims to screen out candidates with a relevant history of misconduct, which may help address the concerns raised. The associated guide also reinforces the need for departments to keep good records to enable validation of the declaration.

3.4 Complainant satisfaction and faith in the system

Poor handling of complaints can result in staff losing faith in the system, which may result in fewer staff making complaints.

Our survey showed that 32 per cent of respondents who made a complaint were not at all satisfied with how the department handled their complaint, and a further 21 per cent were somewhat unsatisfied. The top four reasons for staff dissatisfaction were:

|

Reason |

Result (%) |

|

|

1 |

My complaint was not taken seriously |

30 |

|

2 |

I was not informed of the outcome |

27 |

|

3 |

Communication was poor |

22 |

|

4 |

I was victimised as a result of complaining |

22 |

Note: n=63. Respondents could select more than one answer. Results shown as a percentage of respondents who experienced sexual harassment and made a formal complaint.

Source: VAGO survey 2019.

Complaints not taken seriously

The 21 formal complaints that we reviewed were all taken seriously by the relevant department. However, some respondents to our survey felt that that this is not always the case.

To meet their positive duty under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 to eliminate sexual harassment, departments must ensure that all complaints of sexual harassment are taken seriously and addressed.

Managers play a key role in this. We discuss the importance of training for managers further in Part 4.

Not informing complainants of the outcome

Departments give complainants varying levels of information about the outcome of investigations often due to concerns about privacy. We found some cases where departments did not inform the complainant whether the investigation had substantiated their complaint or not. This can have adverse impacts on the complaint, as outlined in responses to our survey.

In our survey, 27 per cent of respondents who made a formal complaint said they were not satisfied because they were not informed of the outcome.